Abstract

In this chapter, we report on transformations of an entrepreneurial firm during its internationalisation. We propose the use of a prediction/control framework to explain how an entrepreneurial firm gradually changes into a multinational corporation. During the processes of expansion the firm deploys different behaviours that indicate shifting mindsets from approaches that can be characterised as entrepreneurial to behaviours considered as managerial. Following a firm’s development from inception to its end as independent entit,y we discuss how the cross-roads between Entrepreneurship and International Business disciplines might create synergies beyond their own confines by establishing International Entrepreneurship as a meaningful field of study.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- International Business

- Multinational Corporation

- International Maritime Organization

- Entrepreneurial Firm

- International Entrepreneurship

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Entrepreneurs are said to behave differently from managers. This general assumption, which gets considerable backing from different authors (e.g. Schumpeter 1934; March 1991; Stevenson and Gumpert, 1985; Lewin et al. 1999; Zahra and George 2002), is surprisingly little considered in the emerging field of international entrepreneurship (IE). Keupp and Gassmann (2009) analysed a wide array of literature which makes reference to phenomena pertaining to international entrepreneurship and discovered that entrepreneurship contributes little in terms of theoretical input to IE and that international business (IB) on the other hand has a high level of disregard for many of the processes that make firms’ international expansion possible. This is interesting because IE is positioned at the intersection of entrepreneurship and IB research, and the need for a new disciplinary niche would logically stem from the limitations of the two parent disciplines in that they cannot sufficiently explain the phenomenon in isolation (Mathews and Zander 2007). While IB offers a number of theories that explain why multinationals are able to perform better than other organizational forms and approaches (e.g. Dunning 1988), there seems to be little theoretical input that helps explain why firms that are entrepreneurial achieve success in pursuit of internationalization.

This chapter aims to evaluate a particular strand of entrepreneurship theory (Endres and Woods 2009), effectuation theory (Sarasvathy 2001), and uses a model of effectual processes (Wiltbank et al. 2006) as an analysing framework for longitudinal case data to explain how entrepreneurial internationalization may be different from managerial (e.g. firm-specific advantages, location-specific advantages, internalization rationales) behaviour as it is usually assumed in IB theories. In our discussion we propose a number of ideas which may provide new pathways for explaining why multi-national corporations (MNCs), or at least a share of them, might be the result of entrepreneurial effectuation rather than the outcome of rationalized managerial behaviour, which we claim is a logic which applies only under certain conditions and can usually only be rationalized ex post.

Zahra (2005, p. 24) underlines an important fact which he encourages others to take up for further research: ‘[...] we do not know what becomes of those INVs [international new ventures] that survive and become established.’ One assumption is that entrepreneurial firms which manage successful to quickly and extensively internationalize will become similar to other firms in their industry over time (Zettinig and Benson-Rea 2008). We wonder if this is so and why. Logic might command us to believe that start-up firms usually start out small and most of them are entrepreneurial. They internationalize and usually years or decades later they classify as what the field of IB calls multinational corporations. There seems to be one or more breaks in terms of how the firm at one point in time is small and entrepreneurial and at another point in time is large, powerful and multinational. While entrepreneurship research usually focuses on action (Zahra 2005) in the earlier phase, IB looks at firms in the later stage. The fact is that the firm is the same, even though it is difficult to establish what the essence of the firm is that qualifies it as the same firm after time has passed. The firm has developed and changed into something different to what it was at its outset. From a discipline of IE, at its particular disciplinary intersection, we could expect to learn how the firm transforms from its initial entrepreneurial actions to become a MNC.

During the last decade much emphasis in IE has been given to define and qualify quantitative outcomes of international new ventures (compare Fig. 5.1 in Keupp and Gassmann 2009: e.g. degree of internationalization; export intensity; export performance; share of foreign sales) and too little attention has been given to the transformation of the firm and what individuals in it might do in order to create value. It is interesting to explain how the firm becomes international because this involves qualitative changes in behaviour that create value. This is the focus of this chapter and we hope to continue a discussion (e.g. Jones and Coviello 2005) of how entrepreneurial behaviour (Zahra 2005) over time unfolds and results in the multinational corporations with which IB is traditionally concerned.

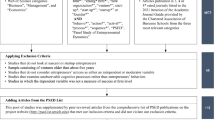

Framework of prediction and control (based on Wiltbank et al. 2006)

From Value Creation Through Effectuation to Entrepreneurial Internationalization

March (1991) defines the long-term survival of the firm as being dependent on its ability to exploit given knowledge while exploring new knowledge in a balanced way. While current opportunities have the advantage of being known, we have difficulties in assessing future opportunities when we are unable to assign risks to them (cf. Knightian uncertainty). Exploitation is the domain of managers (Lewin et al. 1999) when they create value by utilizing their extant knowledge in efficient ways. They can draw on their knowledge and use it for estimating how certain changes unfold and that enables them to utilize sophisticated techniques to plan and execute firms’ behaviour. This involves calculated risk taking, evaluating alternative courses of action and inducing incremental improvements with a high focus on efficiency, all in a fairly systematic and rationalized way. The focus of these actions is on the predictable. The entrepreneur on the other hand has been characterized as an actor who explores new knowledge for finding or generating new opportunities. This involves experimenting with ideas, new technologies and business models. Sarasvathy (2001) distinguishes these two approaches to business based on their process logic. Managerial logic is based on causation processes, formulating objectives and deploying the means to attain these ends. Entrepreneurs on the other hand follow effectuation logic (Sarasvathy 2001, p. 251) which disregards the emphasis on the predictable elements but stresses elements which can be controlled in the process of defining and attaining new value (Sarasvathy et al. 2008). These are the fundamental premises distinguishing the entrepreneurial and the managerial mindsets. These fundaments influence how these types of actors think and act and how they perceive themselves and their firms in relation to the environments they are a part of.

In our view effectuation is a very useful approach for IE because it addresses how the early stage firm (INV) acts, in the absence of relevant knowledge about international markets or how to enter them. In addition, effectuation may contribute to explaining how the later stage firm (e.g. MNC) is a result of qualitative changes that take shape in its initial stages.

To explore this we investigate Wiltbank et al. (2006) who put forward a framework of prediction and control (Fig. 5.1) which depicts the useful mindset differences of actors at different stages, so we argue later, and serves to subsequently investigate the longitudinal case data of a firm which transformed from entrepreneurial beginnings into a complex international company managed by professional managers.

The framework of prediction and control (Fig. 5.1) distinguishes the way different actors compute their environment. It conceptualizes fundamental differences in the way the nature of the environment is viewed and processed. Managerial approaches have a low emphasis on elements which can be controlled despite uncertainty. This means that the firm will either subscribe to stringent planning if data about the firms’ environment is available; or an emphasis on adaptation is given when information about the way the environment will evolve in future is missing and thus predictability about future environmental states is low. While the planning approach has been benefiting from work such as competitive analysis (Porter 1980), the adaptation approach has been conceptualized by work in the area of emerging strategy (Mintzberg 1994) or by approaches to understanding firm adaptive actions as dynamic capabilities (Teece et al. 1997), to name some examples (a wider discussion can be found in Wiltbank et al. 2006).

The right column of the typology depicts entrepreneurial approaches which contrast managerial approaches in that they are driven by a philosophy that the environment can be actively constructed and is not a given set of factors the firm adapts to. A visionary approach assumes that the actor possesses a glimpse of what is to come and therefore acquires and allocates resources toward attaining envisioned opportunities (e.g. Hamel and Prahalad 1991). The fourth type, transformative, shares with the visionary approach in that it emphasizes factors which can be controlled but differs from the visionary approach in lacking the belief that future opportunities exist and can therefore be defined and attained. Instead the transformative approach puts little emphasis on future prediction but is mainly concerned with controlling elements that can be controlled.

The transformative approach has the premise that the entrepreneur understands which means are available and can be influenced to actively seek possible ends based on these controllable elements: thus the belief in the creation of new opportunities based on available own and accessible others’ resources. The key difference of this approach to the managerial approaches on the left side of the framework is the assumption by the entrepreneur that environments can actively be constructed because they are not pre-determined. This approach is convincingly explained and discussed by Sarasvathy and Dew (2005) when they conceptualize entrepreneurial market creation. The entrepreneur starts out with an understanding of who she is; what she knows; and who she knows. With this basic understanding of means she develops goals concerning what is possible. From that first, arguably rather vague goal setting, she starts to utilize her networks of people. She starts to interact with them, presenting initial ideas and vague objectives, convincing some of them to join and commit to the emerging business in various ways. Through these interactions and commitments two effects occur. First, new stakeholders through their commitment provide new means and expand the resource-base of the venture; and secondly, through stakeholder interactions goals emerge and converge, giving the venture direction and focus. While this transformative approach is clear on controlling its means, it is loose on setting goals, which influences the way the firm’s environment is gradually constructed in a dynamic process of interactions with stakeholders of the firm. Thus the environment in which the entrepreneur and her venture operates is the outcomes of interactions with stakeholders.

In the international expansion of the entrepreneurial firm we can assume and observe the existence of a transformative approach. The entrepreneur might have some general resources, maybe a product or service idea, some basic understanding of market dynamics and some ideas about how a market offering might be sold. She then ventures out and utilizes contacts which might be made purposefully or are of a social nature (cf. Coviello 2006) and starts to commit certain partners to the venture with the effect that new environments are created (Sarasvathy et al. 2008) and new objectives within this emerging environment are defined. This process in the end might lead in many cases to the phenomenon of international new ventures as originally defined by Oviatt and McDougall (1994), but may also results in new markets or industries (Sarasvathy and Dew 2005).

In the next section we use the prediction and control framework (Fig. 5.1) and the transformative effectuation process to analyse the case of a hugely successful serial entrepreneur who, over 40 years, created several firms which relatively quickly internationalized and grew to considerable international scope and size, in some product segments attaining global market shares of up to 90 %. What is more interesting for this study is to reconstruct processes of organizational change which occurred through the internationalization of one of his, to date, most successful ventures. For this purpose we use both retrospective and real-time longitudinal observations and multiple respondent interview data which we triangulate with secondary data provided by the case firm and by third parties. It shows how a company starts out with little, internationalizes on a global scale in a relatively short time and how it emerges to be what generally could be regarded as a multinational corporation.

The Hifog Case

Our initial unit of analysis is a long-standing entrepreneur, Göran Sundholm, who received in 2002 the Finnish Engineering Award for pioneering work as an inventor and in the same year the Finnish National Board of Patents and Registration Award. Few other people in Finland have to date been as industrious when it comes to patents, with Göran holding well over 1000 patents or patent pending applications. Göran, with a technical education background, filed his first patent at the age of 17 and a few years later, in 1973, started his first company which focused on high-pressure hydraulics services and systems for the international maritime industry. Many of the technologies his firm developed in the maritime field have been transferred via newly founded firms to create value for other applications in other industries. This modus operandi, to take valuable solutions and find new applications in other industries, has been a characteristic of Göran’s entrepreneurial approach to business. Another characteristic of this entrepreneur’s way of doing things is to actively create opportunities by taking notes of trends that might produce them. He does not consider boundaries such as definitions of specific markets, industries or niches, and has a healthy disregard for competition or rules of industry as limiting factors. By 1985 his first company, GS-Hydro, a company with a 60 million Finnish Marks turnover (equivalent to approximately €18.2 million at the 2010 index-level), had been sold to Kone Corporation, effectively making him a very wealthy man who could have retired. However, he did not and became the enabler for another venture which was created through his interpretation of environmental changes and coincidences.

To understand the subsequent case it is important to know that in 1987 the United National Montreal Protocol banned Halon chemicals, used in automated fire extinguishers, as being hazardous for the ozone layer; and that in 1990 the devastating fire on the cruise ship Scandinavian Star, caused the deaths of 158 people and triggered the UN International Maritime Organization to decree that by 2005 all new and existing passenger vessels must be fitted with automatic sprinkler systems preventing similar tragedies.

These regulatory changes in the business environment triggered one of Göran’s long-standing customers to contact him and in January 1991 requested that Göran ‘ do something’ to solve the problem of conventional automatic sprinkler systems which technically were unsuitable for use on ships. This set in motion a series of events leading to establishing a new venture under the umbrella of his firm, called Marioff. Conventional sprinklers are not an option for ships because their deployment would compromise a vessel’s stability and may result in its sinking. The request by the ship owner ordering a solution to this problem was instantly sealed with an unconventional approach. Göran agreed with the customer on a price for what he thought such a new sprinkler system would probably cost and sold it. The customer made a 40 % down-payment to finance the development of a system that was commissioned as ‘equivalent but lighter’ than conventional systems and to be installed on two new-build vessels within 18 months. In effect Göran had made his first sale for his new venture for a product (Hi-Fog) and product category that did not exist and for a market that was non-existent. (Quote: ‘If you haven’t sold it, there’s nothing to develop. First you need to sell, and then develop. Isn’t that how it usually goes?’) The opportunity though was very clear in Göran’s mind: there were capabilities in terms of hydraulic knowledge and piping; there was a healthy lack of knowledge of existing automated sprinkler systems enabling experimental actions (quote: ‘I once experienced a forest fire when I was about ten years old. That was [all] my experience [with fire extinguishing]’); and there was a clear regulatory induced need for this sort of product. In addition there was good access to discuss this new technology with ship builders, ship owners and operators around the world, an important network in the development of this market which stemmed from his previous ventures.

Göran did not pay too much attention to what competitors were up to; no formal market research activity had been conducted (quote: ‘The only thing we ask is: ‘Where is the order? We don’t waste time on market research’) and there were rather informal exchanges of ideas and presentations to potential customers and other potential stakeholders (e.g. insurance companies and authorities). During the rapid product development that the company carried out at the premises of the Finnish Technical Research Centre (VTT) and the Swedish National Testing and Research Institute (SP) the atmosphere was very open (quote R&D manager: ‘There it felt like every passer-by was invited to see the tests’; quote Göran: ‘Yes: here’s the fire. Let’s see how the system functions’). The mindset had been one that where there is a customer’s order it must be delivered. Göran invested the down-payment of the first client, together with a calculated €7 million of his own money and a great deal of confidence to deliver a solution (quote: ‘We didn’t have a clue what we were promising, and luckily so. I don’t think we would’ve promised anything otherwise’).

Three months later, in April 1991, the prototype was introduced at the Cruise and Ferry exhibition in London and by 1995 the company had established the global maritime automated sprinkler business. During these first years Göran used his personal contacts to ‘most’ (quote) of the world’s major shipping companies to introduce the product and its advantages, heavily supported by reference to the first industry sale. After capturing most of the maritime automated fire extinguishing system market globally (by 2005 an approximately 90 % global market share in new vessels) the firm started to extend its focus to onshore business, where they met considerable opposition from established competitors. Focusing initially on the US market as the biggest market for sprinklers, rivals used all kinds of protective measures (e.g. lobbying) to assure that the new sprinkler system would not get accepted by major stakeholders (e.g. insurance companies, authorities) and that heterogeneous national regulations would be slow to acknowledge the superior water-mist-based systems of Marioff. The firm finally succeeded in making major sales in key onshore markets by 2000 and has since steadily extended its market share, leading to partial sale of the company in 2001 (in order to raise €50 million in capital) for fuelling further expansion and for Göran to finally sell his remaining personal ownership of the company in 2007.

Organizationally Marioff employed 14 people at the beginning of Hi-Fog’s development in 1991. The business had no formal strategy and according to the R&D Manager ‘no organization’. The emphasis was on getting things done rather than being formalized. Decisions were taken quickly, if not instantly, and in an autocratic fashion by the entrepreneur (quote: ‘It was quite easy, I decided everything’). The company tended to make sales often without formal contracts but relied heavily on utilizing Göran’s access to main players in the maritime business all over the world. Very often international sales have been agreed, installations started and down payments made within a week. By 2002 turnover reached €64 million and the workforce had grown to 307, with about a third of staff located around the world. Over the years foreign subsidiaries had been established at major locations for this rather global industry, including a local presence in Norway, 1995; Sweden, 1997; Denmark and the USA, 1998; the UK, 1999; Spain, 2000; Italy and France, 2001; Singapore, Germany and Canada, 2002, etc. Around the year 2001 the business had grown to a considerable size and had diversified its offerings into many sub-markets of the overall sprinkler market, developing from offshore to onshore markets, and creating applications for special requirements like storage rooms, tunnels, churches, and hotels. To fuel this rapid expansion into new and little known onshore markets, and to acquire management experience, Göran sold 50 % the company to a private equity firm, raising €50 million. From this point on the company changed considerably. An outside manager had being appointed as CEO and formal structures and processes started to be introduced in the firm (quote R&D manager: ‘Well, I’d say it was around the year 2000 when things started to get more ordinary. It started to become an ordinary, boring company. It seems with growth comes bureaucracy’). After a successful entry into onshore markets Göran sold his remaining share of the company in 2007 for €132 million.

In terms of objectives, at the beginning of its development in 1991, the firm did not make any effort to quantify the opportunity or to espouse goals for the business. It was clear that the problem they were trying to solve was a serious one for the shipping business and their objective was to deal with it by developing a technology. It was also clear that the nature of the shipping industry was international and that the scope of such business would have global potential, but besides this simple and taken-for-granted understanding was that the initial focus was heavily geared toward fulfilling the first order, at any cost. The approach to establish the business was simple: make sales and deliver. Decision making was quick and usually sales were done without written contracts and the installation and delivery of systems were covered by down payments.

In terms of rapid product development co-operation with SP and VTT was vital because it added expertise in different aspects of the development and created new ways of looking at things. Business development was heavily influenced by interactions with different stakeholders, especially potential customers, first off-shore, which was achieved by a very open approach involving visiting all of the main international players and presenting the product at fairs and conventions. Entering onshore markets though was a different story. Since the company did not create a new market it needed to adhere to the rules of the game in the industry, which created considerable barriers by substantial lobbying against the new technology. This required the company to substantially change its approach in order to grow further and subsequently led to the need for professional managers to adapt the firm to this new situation. Since 2007 the company is a subsidiary of UTC, the 91st largest US Corporation (Forbes 2015 List).

Case Analysis

The case illustrates overall how a small entrepreneurial firm transforms gradually over time into a multinational company. At the beginning some changes in the institutional environment of the global shipping industry set the stage for an emerging need by shipping companies to find a solution to a serious problem. Subsequently we use Wiltbank et al.’s (2006) prediction and control framework (Fig. 5.1) to analyse how the firm’s approach to business changes throughout its internationalization and organizational development. We distinguish the longitudinal development in four stages which have important implications for the entrepreneurial firm in emerging as a global player in the maritime fire protection market and beyond.

The Visionary Stage

At the very beginning, in 1991, the entrepreneur did not have any plans or visions to engage in maritime fire protection. An initial vague vision was brought to the entrepreneur’s awareness in the form of an expressed need for a solution by a ship owner who had two new vessels under construction. It was easy to envision that certain changes in the regulatory environment could bring considerable opportunities in the long run (the International Maritime Organization, a UN unit, decreed that by 2005 all new and existing passenger vessels must be fitted with automatic sprinkler systems). Then current technologies were unfit to satisfy these demands (in 1987 the United National Montreal Protocol banned Halon chemicals which were used in fire safety; traditional water sprinkler systems failed to comply with industry standards). This provided some sort of visionary certainty, in our view a key defining factor for a visionary approach, that there will be a market even though this market might be so far in the future that it cannot be justified in terms of conventional business logic. The unconventional acceptance of a down payment for a new revolutionary system (many tried before but failed to solve inherent problems with high-pressure mist sprinkler systems) and delivery within 18 months quickly diverted the attention away from envisioning future market opportunities further and set the focus on developing the technology and delivering what had been sold. While there had been the vision that this is a big market, it was not considered to be important at that stage to quantify what the implications for product or business development may be or to develop an express strategy to attain this result.

The Transformative Stage

This phase provides a key in understanding how internationalization unfolded and how the entrepreneurial organization was shaped by actions rather than plans. The entrepreneur at the beginning of the venture in 1991 focused with perseverance on fulfilment of the first order. The interesting aspect here is that the sale and payment concerned a completely unknown technology at that stage and it triggered processes of effectuation (Sarasvathy and Dew 2005). Göran, through his previous business experiences, had the self-confidence to sell systems in areas he considers his expertise without actually having the solution. This is critical for the development of the venture because it emphasizes the mindset and understanding of who the entrepreneur is and what his capacity and identity is. Much of what happened after reflects this approach to doing business, even more so than the enthusiasm for solving challenging technical problems (Sandberg et al. 2013). In addition he had more than 20 years’ experience of fitting hydraulic systems onto ships, which provided the essential knowledge needed for a solution. The third category of means encompasses the established network of contacts and relationships with many different stakeholders, most importantly ship builders, owners and operators, plus other stakeholders used to support the development of the technology (Sarasvathy and Dew 2005). With this understanding and a first commitment it was crucial to focus attention on the technological research and development, which at that point did not have any clear shape, with the business rationales at this stage clearly being secondary. The entrepreneur started to collect the stakeholders needed to find a solution (engineers, testing institutes, and potential customers interested in the development) The initial sale could also be seen as important due to the legitimacy it created ex-ante and the trust that this was a serious effort to solving a major problem for the industry. With more stakeholders committing over time new means were brought into the venture’s extended resource base, something that has also been found to be a necessary condition for the establishment of international new ventures, in that it allows a venture to access others’ resources (Oviatt and McDougall 1994). Through its interactions the venture also developed its trajectories that determined how the business side developed and when and where subsidiaries were set up around the world; and later setting actions in motion for entering new business markets beyond the shipping industry. This stage lasted approximately from 1991 to 2000 until the entrepreneur decided that a harder push was needed to enter existing fire protection markets onshore. During this stage, while the main focus was the vast global shipping industry, many other markets were identified and the firm started to market its products against the strong competitive reactions of existing market players. What is interesting in this phase is that the off-shore market for sprinkler systems did not exist prior to Marioff creating it, thus it was able to set many of the rule that created the market. The desire to grow the business to capture much larger opportunities in existing markets, markets which were well structured in terms of competition and which had their own practices in place, required major changes for the company which was thus far used to define rather than following the rules of industry. The rationale of needed change to capture growth opportunity led Göran to bring in new capital and new knowledge in the form of a private equity partner. This partner initiated critical organizational changes in the firm. This phase of organizational development can be considered ending at that stage with the new partner restructuring the firm by hiring professional managers who started to put in processes that were found necessary to prepare the organization for systematically approaching existing markets, leading to the next stage.

The Adaptation Stage

While the previous stage can be characterized as emphasizing elements the firm can control and thus enables it to shape its own business environment, this stage can be interpreted as one in which a relative loss of control was accepted in order to capture a huge opportunity. At the same time the firm, which had established the rules of the game for offshore sprinkler systems (due to previous knowledge of many aspects of offshore business generally, and having many relationships available to the entrepreneur) found it was different for the endeavour to enter the onshore market. The firm had to first learn how that existing market functioned, which mechanisms were used by competitors and what needed to be done to enter this industry with a superior technology but lack of understanding about the business. To compensate for the shortcomings managers were brought in who started to adapt the firm to this new environment. They started to evaluate how existing processes and capabilities could fitted into these substantially different industry structures in these markets around the world, especially in the USA. This loss of control over the means and lack of knowledge of how the industry does business represents low predictability due to the many unknowns (e.g. how important stakeholders like insurance companies can be won over while existing market players heavily lobby against the new technology) and means that adaptation requires organizational flexibility to fit into the industry, while paying much attention to what is happening on the market. In organizational terms the stage change from transformative to adaptive has also influenced the organizational culture and the way the firm has been doing things. Emphasis was given to managerial processes, analysis, and systematic approaches to conquer new industries and markets. Many of the key individuals who joined the firm early started to lose interest in working for a ‘normal and boring’ company. This might have subsequently led to its change into the fourth stage.

The Planning Stage

With private equity partners acquiring half of the firm and with managers taking charge of the firm, including taking the post of CEO, Göran, the entrepreneur who was still the president of the board, handed operational business over to managers. With this loss of direct control over critical elements and actions in the business he also lost his passion for it leading him to invest increasingly more time in separate new ventures. Subsequently, the conclusion was to sell the firm to a giant MNC with strong market share in the global fire protection industry. This decision led to the acquisition of Marioff and the integration of its business with that of an established competitor in an industry which overall can be characterized as fairly stable and thus rather predictable (for established insiders).

This case illustrates a firm’s transformation from its unconventional entrepreneurial beginnings to becoming quite a regular business in its industry. What is interesting is the way the firm shifts its approach from being entrepreneurial to becoming a managerial company. In the first two phases it was critical to control certain means and expand them through developing new value by exploring stakeholder interactions and to stay open to allowing the business first to develop its value creating technology before defining any organizational goals. The decision to enter existing markets and the subsequent shift to a managerial orientation can be interpreted as loss of control over the environment, and at the same time it can be seen as a transition phase in which the firm tried to become organizationally flexible while learning fast what the rules of the game are. Value creation at this stage is hanging in the balance between the huge technological value of the product and the lack of know-how in terms of commercializing it in new markets. Because the market for shipping fire protection systems was created by the firm it had widespread control over it. Expanding the firm to existing markets meant a relative loss of control and in parallel having little insight into the mechanisms of an existing industry. To overcome this the answer was to apply managerial logic, acquire the lacking knowledge in the form of new managers and to start exploiting this knowledge to leverage the superior technology, which was fully realized when the whole venture was finally exploited via an industry sale, transforming the business into a conventional one.

Discussion and Conclusion

The case describes one and a half decades of the development of an entrepreneurial firm that managed within only a few years to expand its business worldwide. Our analysis was using effectuation as an entrepreneurship theory (Sarasvathy 2001) and a prediction-control framework (Wiltbank et al. 2006) to show how a firm is able to create value throughout different stages of its development, drawing on different mechanisms that allow the venture to establish and expand internationally and in global market niches (cf. Sarasvathy and Dew 2005). We applied this framework and theory with a process philosophy in mind, emphasizing the events and unfolding changes that happen over time (Van de Ven and Engleman 2004) rather than fitting the case into a certain quadrant of Wiltbank et al.’s (2006) framework. As a result we gained a number of insights which might be further discussed.

First, overall effectuation (Sarasvathy 2001) is a theory which might serve IE to substantially advance its further development as a discipline because it enables us explain different approaches and mindsets of international value creation vis-à-vis the developmental stage of the organization and the opportunity that is being realized. It is a useful entrepreneurship theory which convincingly explains how entrepreneurs function differently from managers and therefore provides a basis to further develop gap filling knowledge about how MNCs emerge from small entrepreneurial firms. In combination with that, the larger framework of emphasis and control (Wiltbank et al. 2006) is useful. In that framework effectuation is positioned as a transformative approach which entrepreneurs apply. As such it helps us understand the mindset and subsequent actions of entrepreneurs and the development of their firms as it explains why and when firms change behaviour in their development. As our case analysis has shown there is substantial explanatory power in investigating how behaviour is changing with varying degrees of belief in predictability and control. We recommend that that this framework is used to consider possible developments rather than being used as an ordering framework for when firms developing knowledge of dynamic processes of the internationalising entrepreneurial firm. That this framework is used to consider possible developments rather than an ordering framework for firms. We have seen with the Marioff case that a firm may go through several stages, and we have been able to explain how a development from visionary to transformative to adaptive to planning occurs in relation to the shifts from an entrepreneurial to a managerial firm, which draws on different rationales and processes, usually expressed as balancing exploitation of given and development of new knowledge (March 1991), in the way it creates value.

Secondly, the use of the control and prediction framework, supported by effectuation theory, provides IE with the means to combine knowledge of how entrepreneurs function with knowledge about the MNC. It may provide explanations as to why young firms have been found to have certain advantages in their early internationalization (Autio et al. 2000) compared to older (more managerial) firms. It also gives us a framework to explore new ways of investigating what happens at the ‘phase change’, when the firm switches from entrepreneurial to managerial behaviour and opens up new ways of looking at qualitative changes within the firm. This might add to our understanding of the process of internationalization as, for instance, prominently described by Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 2003) and it might establish differentiated views on the mechanism of how value is created in the process. Entrepreneurs tend to process reality in different ways than managers do (cf. Sarasvathy et al. 2008, p. 46), which should influence the way the firm processes its knowledge and makes decisions concerning market entry and value creation.

Thirdly, arriving at IB, this approach to look at qualitative changes in the firm from its entrepreneurial beginnings to its development into a MNC might give us insights into the making of MNCs. Currently, major theories about foreign direct investment (e.g. Dunning’s Eclectic Paradigm) tend to accept the fact that a MNC’s success in terms of its value creation capacity can be explained by a number of factors, like firm-specific advantages, location-specific advantages and internalization choices. It nevertheless does not help us understand how these types of firms came to enjoy these advantages in the first place. In that respect IB would not only be influential for IE but IE could contribute to answering some fundamental questions about IB.

Fourthly, most influential theories developed for MNCs and INVs (e.g. Oviatt and McDougall 1994) are ex-post rationalizations of successful outcomes. We suggest investigating the development of entrepreneurial firms which might grow into MNCs, applying a process theoretical lens and using event-driven methods (e.g. Aldrich 2001; Van de Ven and Engleman 2004). This approach may help us learn more from failures, for instance when entrepreneurial firms fail to recognize their limitations when constructing their environments, or under which conditions such limitations might be encountered.

In addition it is important to analyse what the boundary conditions are under which such a new theoretical trajectory using effectuation logic applies. We suggest that firms should be investigated in terms of their mindset at the onset of their internationalization. How do they see their future? Do they emphasize understanding international environments and prediction of what their environments might become? Or do they focus on elements which they can actively control? This is all in all a very interesting question, which has already, in fields other than IB, created paradigm wars (cf. McKelvey 1997), by debating whether the firm needs to respond to naturally occurring phenomena outside its own direct influence or make its own decisions which influence its further development. As our approach to explaining entrepreneurial internationalization has shown, it may be that both paradigms are valid at different stages of a firm’s development and to different degrees. What is important is to investigate the actions of internationalizing firms over the course of their development with one critical phase being the phase change from entrepreneurial to managerial.

Further research should be directed to put emphasis on the behaviour of internationalizing firms and towards the mindset they have at various developmental stages. For entrepreneurial firms that become managerial MNCs it might give substantial insights into how to benefit from the different operating logics of entrepreneurs and managers, and to accept clearly what constitutes the boundaries of either approach in order to optimize the international development of such firms. In addition this might lead us to a new way of making sense of a new discipline which integrates vast knowledge of IB with new theoretical insights in entrepreneurship, and in return provides answers to some of the larger remaining questions in both parent disciplines.

References

Aldrich, H. E. (2001). Who wants to be an evolutionary theorist: Remarks on the occasion of the Year 2000 OMT distinguished scholarly career award presentation. Journal of Management Inquiry, 10(2), 115–127.

Autio, E., Sapienza, H. J., & Almeida, J. G. (2000). Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity and imitability on international growth. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 909–924.

Coviello, N. E. (2006). The network dynamics of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(5), 713–732.

Dunning, J. H. (1988). International production and the multinational enterprise. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Endres, A. M., & Woods, C. R. (2009). Schumpeter’s conduct model of the dynamic entrepreneur: Scope and distinctiveness. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, (online first). doi:10.1007/s00191-009-0159-3.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1991). Corporate imagination and expeditionary marketing. Harvard Business Review, 69(4), 81–92.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J-E. (1977). The Internationalization Process of the Firm—A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2003). Business relationship learning and commitment in the internationalisation process. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 83–101.

Jones, M. V., & Coviello, N. E. (2005). Internationalisation: Conceptualising an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(3), 284–304.

Keupp, M. M., & Gassmann, O. (2009). The past and the future of international entrepreneurship: A review and suggestions for developing the field. Journal of Management, 35(3), 600–633.

Lewin, A. Y., Long, C. P., & Carroll, T. N. (1999). The coevolution of new organizational forms. Organization Science, 10(5), 535–550.

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

Matthews, J. A., & Zander, I. (2007). The international entrepreneurial dynamics of accelerated internationalisation. Journal of International Business Studies, 38, 1–17.

McKelvey, B. (1997). Quasi-natural organization science. Organization Science, 8(4), 352–380.

Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning: Reconceiving roles for planning, plans, planners. New York: Free Press.

Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 45–64.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

Sandberg, B., Hurmerinta, L., & Zettinig, P. (2013). Highly innovative and extremely entrepreneurial individuals: What are these rare birds made of? European Journal of Innovation Management, 16(2), 227–242.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263.

Sarasvathy, S. D., & Dew, N. (2005). Entrepreneurial logics for a technology of foolishness. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 21, 385–406.

Sarasvathy, S. D., Dew, N., Read, S., & Wiltbank, R. (2008). Designing organisations that design environments: Lessons from entrepreneurial expertise. Organization Studies, 29(3), 331–350.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Stevenson, H. H., & Gumpert, D. E. (1985). The heart of entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 2, 85–94.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

Van de Ven, A. H., & Engleman, R. M. (2004). Event- and outcome-driven explanations of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 343–358.

Wiltbank, R., Dew, N., Read, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2006). What to do next? The case for non-predictive strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 27, 981–998.

Zahra, S. A. (2005). The theory of international new ventures: A decade of research. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(1), 20–29.

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). International entrepreneurship: The current status of the field and future research agenda. In M. Hitt, D. Ireland, D. Sexton, & M. Camp (Eds.), Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating an integrated mindset strategic management series (pp. 255–288). Oxford: Blackwell.

Zettinig, P., & Benson-Rea, M. (2008). What becomes of international new ventures? A coevolutionary approach. European Management Journal, 26, 345–365.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and the Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zettinig, P., Sandberg, B., Fuerst, S. (2017). Value Creation During Different Development Stages: What Changes When an Entrepreneurial Firm Transforms into a Multinational Corporation?. In: Marinova, S., Larimo, J., Nummela, N. (eds) Value Creation in International Business. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39369-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39369-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39368-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39369-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)