Abstract

This chapter presents a collaborative research project carried out with six Geneva primary school teachers. The focus of the project was on teachers’ practices of collaborative assessment for learning in their classrooms. The main features of collaborative research are presented, in particular the process of co-construction between researchers and practitioners of a significant project for both the scientific and the professional communities. Interplay between professional development seminars and teachers’ classroom experiences was at the heart of the project. Support for teachers’ learning was provided by the articulation of conceptual tools proposed by the researchers with concrete tools and data coming from the teachers’ classrooms. The conceptualization of collaborative assessment for learning in classroom included both individual and group self-assessment procedures in the context of student work in small groups. An overview is given of the principal themes emerging during three professional development seminars and the intervening experiences in the classrooms. One particular theme is developed in order to illustrate the exchanges and issues considered by the participants. This theme concerns the focus of collaborative assessment for learning on social and/or academic objectives and the corresponding assessment criteria. It highlights teachers’ representations about collaborative assessment and, more broadly, their stance and sense of their responsibility with respect to assessment of student learning. The chapter’s conclusion outlines some recommendations for professional development in the context of collaborative research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Professional Development

- Collaborative Research

- Assessment Practice

- Classroom Experience

- Academic Learning

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The research literature frequently points to collaboration among professionals as a factor that can sustain professional development at both the individual level (e.g., a teacher’s professional skills and identity) and the collective level (e.g., a school as a learning community) (Gosselin et al. 2014). Bergold and Thomas (2012) define several fundamental principles which guide participative and collaborative research approaches. They state: ‘A “safe space” is needed, in which the participants can be confident that their utterances will not be used against them, and that they will not suffer any disadvantages if they express critical or dissenting opinions’ (our translation). It is also essential to involve the target community directly concerned by the research issue; this means stakeholders are considered as ‘co-researchers.’ Although different degrees of participation are possible, the determining condition for Bergold and Thomas (2012) is to deeply involve participants in the decision-making process during the research project.

In the field of education, Desgagné (1997) proposes two interrelated goals which characterize collaborative research. The first goal is to support teacher professional development through research. This means ‘encouraging the teachers to question and refine their practices and to work together on a wide range of shared problems relating to contemporary education’ (p. 36 our translation). The second goal is to provide adequate conditions for the production of scientific knowledge about the teaching practices being studied. Several features of collaborative research are highlighted by the literature, in particular: research questions should be significant for both the scientific and the professional communities; knowing is closely linked to concrete actions; research is seen as a collective enterprise involving co-construction of shared meanings by participants; situated teaching practices are collectively analyzed; critical reflection by both practitioners and researchers is expected in a transformative learning perspective (Bourassa et al. 2007; Vinatier et al. 2012).

This epistemological stance of collaborative research seems particularly relevant for investigating classroom assessment practices in order to better understand professional assessment cultures, teachers’ values, the conditions of their authentic practices, and the resources supporting their transformation (Mottier Lopez, in press). We adopt a situated perspective on professional development, seen as closely linked to collective practices of collaboration (Lave and Wenger 1991). In this perspective, individual dimensions (skills, values, identity, personal history) and sociocultural aspects of teacher learning and practice are seen as mutually constitutive. Moreover, the collaborative research group can be conceived as a learning community composed of distributed expertise between practitioners and researchers.

This chapter presents a collaborative research project that concerns collaborative assessment for learning (CAfL) in the classroom. The expression ‘collaborative assessment’ can refer to practices developed by groups of teachers outside the classrooms, including social moderation of assessment judgments (Allal and Mottier Lopez 2014). In the classroom, this expression can refer to students working together to co-construct shared appraisals about individual contributions to group work or about the contribution of the group as a whole to the implementation of the task. In our research, both contexts of collaboration are present: (1) between teachers and researchers in the context of collaborative research, (2) between students, in interaction with their teacher, in CAfL activities in the classroom.

In the spirit of collaborative research, the questions about CAfL must address both scientific and practical concerns. The main questions defined by our research group are the following:

-

At the scientific level: The current literature makes increasing reference to collaborative assessment. But what justifies this designation in relation to other well-known forms of assessment involving interactions between students and between students and the teacher? What broader conceptual framework can be developed for CAfL practices?

-

At the practical level: Small-group work is encouraged by the school system directives and the curriculum material used by the teachers. What sort of assessment for learning can be developed for situations of small-group work? What are the objectives to be targeted in CAfL? How does the time frame of CAfL fit in with teaching and learning processes? How can CAfL be implemented and managed in the classroom?

In a collaborative research approach, researchers do not have a value-neutral stance, nor an external position. An in-depth relationship between researchers and practitioners is needed to co-construct meanings and to sustain an ongoing dialogue between their respective viewpoints (Desgagné 1997). The following sections of this chapter present the research context, the participants, and some major findings regarding teacher professional development in the context of our collaborative research.

2 Research Context and Participants

Our research was based on alternation between professional development seminars and teachers’ classroom experiences conducted over an entire school year. To participate in the project, the teachers agreed to contribute to the design of new assessment practices and the experimentation of these practices in their classes. This meant: (1) during the seminars, participating in the co-construction of a shared framework for developing new classroom practices, (2) hosting a researcher (second author of this chapter) in the classroom to observe the practices experimented, (3) holding discussions with this researcher outside the seminars in the form of research interviews, (4) accepting that the assessment practices observed be collectively analyzed and discussed during the subsequent seminar, (5) and starting the cycle again. This alternation aimed at creating conditions for in-depth exchanges, including possible socio-cognitive conflicts between participants, as well as negotiation of new meanings linked to experiences carried out in the authentic environment of teaching practice. The seminars were conducted by the two authors of this chapter, but the classroom observations and interviews with the teachers were carried out by the second author in the context of his ongoing doctoral research (Morales Villabona 2013).

The research was conducted in the context of the second cycle of primary education in the canton of Geneva (grades 5–8: 8–12 year-old studentsFootnote 1). Each year, Geneva primary school teachers have to participate in 14 h of professional development activities which they can choose from a catalogue of offers. These 14 h take place during school hours. We proposed an offer entitled ‘Classroom assessment and group work.’ In the description of our offer, we formulated the following questions: What are the different formative assessment procedures that can be envisaged for student work in small groups? To what extent can these assessment procedures support students’ skill in assessing themselves or their peers when working in groups? How can group work and student learning be assessed? Our proposal also explained both the professional development and research goals of the project, and the conditions of participation mentioned above.

Table 10.1 presents the characteristics of the six teachers who chose to participate in our project. Five of them were classroom teachers while one was responsible for providing pedagogical support to classes in her school (designated as GNT in the table).

The 14 h of the seminars were distributed over the first semester of the school year, with one full day to initiate the project (September 2013), followed by two half-days (October 2013, January 2014). Classroom experiences were observed between the seminars and the observing researcher prepared a support document for the discussions in the second and third seminars. During the second semester of the school year, a long-term observation was conducted in the classes of each of the five classroom teachers. A half-day review brought the project to a close at the end of the school year (June 2014).

3 Professional Development Seminars Articulated with Classroom Experiences

This chapter focuses on the activities carried out in the first semester. We recorded all verbal exchanges and we collected written documents produced during the three seminars. For each seminar, we formulated a ‘synopsis’ based on the methodological principles defined by Schneuwly et al. (2006). Using this tool, we identified the main themes discussed during the seminars, their succession, duration, and hierarchical structure (themes and subthemes). The notion of theme refers to the objects of concern which emerged from the process of developing a local understanding shared by the participants (Voigt 1985). We transcribed excerpts of significant interactions in the negotiation of collective meanings of CAfL and interpreted these excerpts through an ‘analysis by conceptualizing categories,’ as defined by Paillé and Mucchielli (2012). Appendix summarizes the results of these analyses for each seminar: (1) the succession of themes of discussion, (2) the decisions taken collectively at the end of the seminar concerning the experiences to be conducted in class, (3) the teachers’ own initiatives outside the seminars.

3.1 Rationale of Professional Development Seminars Articulated with Classroom Experiences

As highlighted above in our epistemological stance, we wished to investigate CAfL in collaboration with the teachers. Our purpose was not to offer a predetermined model but to co-construct shared principles based on both scientific knowledge and teachers’ knowledge, in a distributed expertise perspective (Salomon 1993). The principles co-constructed by the members of the research group constituted a negotiated framework that could still be reviewed as the classroom experiences progressed and were collectively analyzed. In this sense, our approach followed the argument by Lussi Borer and Muller (2014) that, in the context of teacher education: ‘prescriptions and knowledge should not be transmitted as such, but as objects to be re-normalized, in other words as rules that are resources for action and need to be tested through action and revised (if necessary) according to their viability’ (p. 66, our translation).

Each seminar was conducted according to a scenario we had prepared. The first seminar lasted one full day in order to discuss the research orientation and develop the initial professional development questions. It started by an activity of collaborative drafting of a text, in groups of three. The teachers had to co-write a short article that would be suitable for publication in a professional journalFootnote 2 on the topic: ‘assessment and student group work.’ The purpose of this activity was to allow the teachers to experience the process of collaboration when carrying out a complex task, including reflections on the implications for collaborative assessment for learning. We proposed several resource documents about the forms of self-assessment (see below, Fig. 10.1) and about co-writing procedures. On the basis of this activity, teachers and researchers began to co-define what CAfL in classroom might concretely represent. Initial shared principles for CAfL were co-constructed and first decisions concerning the experiences to be conducted in class were taken.

All the tested classroom activities were based on the teachers’ existing practices, taking into account what they felt they could achieve, given the official school curriculum and their classroom contexts. This choice was justified for two reasons: (1) to ensure strong ecological validity of the data; (2) to take fully into account the teachers’ professional knowledge. Nevertheless, some constraints were also collectively adopted regarding the common features of the classroom experiences: namely that an academic task chosen by the teacher would be carried out by students in small groups and that a procedure involving a collaborative self-assessment tool would also to be implemented by the students.

In addition to these general constraints, we provided an open-ended planning tool for the design of the classroom activities. It listed the main aspects to be considered by the teacher: the academic activity chosen, the objectives and assessment criteria, the way the students are involved in assessment procedures, the teacher’s role, and other new elements to be experimented. This tool can be considered as an ‘affordance’ (Reed 1996) for the collective discussions and for designing CAfL practices. Its role is both to constraint and to support reflective activities, decisions to be taken, and their regulation.

The teachers, on their own initiative, decided to meet outside the seminars or to communicate by e-mail in order to work together on the development of the assessment procedures to be implemented in their classrooms (see Appendix). We consider these teacher initiatives as a sign that the project was significant for them, that they saw themselves as authors and partners of the common project.

The second and third seminars were conducted in a similar manner: first, a time for the teachers to freely share the assessment practices carried out in their classrooms; then, structured discussions based on a document prepared by the observing researcher. This document included transcribed excerpts of students’ interactions during group work and when carrying out CAfL procedures, as well as the different assessment tools developed by the teachers. By presenting these data, our purpose was to allow teachers to acquire a new perspective on their practices and to engage in critical collective thinking. Thus, questions were refined and new shared principles for CAfL were developed, which in turn fed into new classroom experiences, in a continuing process.

3.2 Conceptual Orientation of the Seminars and Themes of Collective Discussions

During the period 1995–2005, a key educational reform was introduced in the canton of Geneva. It played an important role in introducing primary school teachers to the aims of formative assessment, from the involvement of students in the assessment process to the importance of incorporating assessment into daily teaching and learning activities. The practices associated with different forms of self-assessment and with the regulation of learning through formative assessment (Allal and Mottier Lopez 2005) are largely covered in the teachers’ initial training, and are then revisited during professional development activities. Although it cannot be assumed that these elements are fully integrated into the practices of Geneva primary school teachers, it is possible to consider that they are part of their professional culture. In this context, we deliberately chose to orient the seminar discussions towards formative assessment procedures involving student peer groups. This choice was coherent, firstly, with the curriculum material used by the teachers, which emphasizes small-group work by students, and secondly, with the primary school directives which do not authorize summative assessment of student group work.

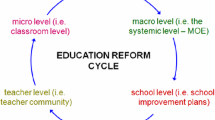

In our project, collaboration between students in the classroom context concerned (1) the academic task carried out in small groups, and (2) the self-assessment process undertaken by the students. The conceptual tool we elaborated for the teachers was based on the idea that collaborative assessment ‘can include self-assessment by individuals or by the group as a whole of the product they have generated, and/or their respective contributions towards the product’ (Race 2001, p. 5). Figure 10.1 presents the tool we proposed to the teachers. Two main levels are differentiated:

-

The first one refers to self-assessment by a student concerning the individual or collective contributions to the task carried out by the group;

-

The second one refers to self-assessment by the student peer group concerning the individual or collective contributions to group work. In this case, self-assessment (by the group as a whole) requires dialogue, the confrontation of different viewpoints, and the construction of shared appraisals.

Although the teachers had some experience with the first level, the second level was new for them.

This conceptual tool was aimed at supporting the design and the experimentation of different CAfL procedures in class. It was designed to be simple and straightforward so that the teachers could easily appropriate the categories. It allowed them to share a common language, to be able to designate the self-assessment level (individual versus group) under consideration, and to collectively imagine concrete examples and practical modalities of CAfL.

Appendix shows the progression of the discussion themes and the detailed questions emerging through collective reflections in the seminars, in relation with the classroom experiences and the data gathered by the observing researcher. Table 10.2 summarizes the principal CAfL dimensions that were particularly relevant for the research group: (1) the individual and group levels of CAfL, (2) the criteria defined in CAfL tools and their uses, (3) the social organization of CAfL (small-group work and whole-class discussions). Table 10.2 also mentions decisions taken regarding successive classroom experiences (in the table: For Cl-Exp) and the new questions (NQ) resulting from the dynamic interplay between collective discussions and classroom experiences.

Starting with the initial shared idea that CAfL should have a formative function, the research group was essentially concerned with the kind of student learning that CAfL should support (academic and/or social skills) and with the challenge of designing collaborative self-assessment procedures for students working in small groups. Technical and procedural aspects then had to be considered: What sort of tools can be constructed? Which criteria could best support student collaboration? How to use criteria with the students? Substantive issues linked, for instance, to the regulation of student learning became significant only after the first classroom experiences and collective discussions.

3.3 The Type of Learning Assessed: Social and/or Academic Skills?

To conclude this section of the chapter, and in order to illustrate how the exchanges unfolded, we will discuss one particular theme which was recurrent throughout the seminars. This theme concerns the choice of the objectives targeted by CAfL. Across the three seminars, an evolution was observed in the teachers’ stance and sense of their responsibility toward assessment of student learning.

3.3.1 First Seminar

At the first seminar, during the collaborative writing task, the teachers asked themselves how to articulate transversalFootnote 3 objectives (in particular, social skills) and academic objectives in order to assess group work: How can the development of social skills be combined with the acquisition of academic knowledge? Should one be favored over the other in the context of CAfL? The teachers’ opinion was to begin by supporting the development of social learning in group work in order to create adequate conditions for academic learning. One teacher stated that ‘it perhaps makes sense to teach the students to work in groups first before subsequently introducing learning [academic objectives]’ (teacher 3, school 1).

As researchers, we participated in this debate by stressing that this issue was very relevant, including from our scientific perspective. While not saying whether it would be preferable to begin by one or the other, we highlighted that transversal and academic objectives are closely interrelated in the situated learning perspective we adopt. We explained that, in this perspective, the conditions in which knowledge develops (here, the social forms of student participation in small-group activities) are seen as an integral part of what is learned (Brown et al. 1989). Consequently, both kinds of objectives should be included in CAfL concerning an academic task carried out in small groups. The teachers seemed not to be totally convinced by our researcher viewpoint and theoretical argumentation. For them, if the aim for the students is to collaborate in accomplishing an academic task, CAfL must first target the social skills required. Thus, one teacher stated that ‘self-assessment will concern the collaboration between the students more than the content [academic learning] … we can include elements of the content but they don’t have to do everything’ (teacher 1, school 1). The teachers’ worry was to avoid overloading the students with the two kinds of objectives. At the end of this first seminar, the research group chose to focus on self-assessment procedures at both individual and group levels concerning how students work together when performing an academic task.

3.3.2 Second Seminar

At the beginning of the second seminar, the teachers were invited to express their impressions about their first classroom experiences, with which they were relatively satisfied. They were especially pleased with the degree of autonomy shown by their students during the group work and the assessment procedures. Assessment tools constructed outside the first seminar were presented. Most of the assessment criteria defined by the teachers focused on ‘participation,’ ‘group functioning,’ and ‘group collaboration.’ The way the students indicated their appraisal with respect to each criterion varied between the classes: a four-point frequency scale was proposed in some classes, a dichotomous ‘yes/no’ scale, with spaces for open-ended commentary, was proposed in other classes.

Some criteria called for an individual self-assessment about one’s own participation or cognitive contribution, for example:

-

I listened to the ideas of my classmates.

-

I proposed sentences for the text we are writing.

Other criteria solicited self-assessment at the group level, essentially about contributions of the group as a whole, for instance:

-

We listened to everybody’s opinion.

-

We spoke softly so we did not disturb the others.

-

We avoided off-task talk.

-

We worked effectively as a group.

A few criteria were about cognitive aspects required by the academic task, for example:

-

I feel able to explain the two themes we worked on.

-

Each member of the group practiced explaining the content of the reading.

We noted that the different levels distinguished by the conceptual tool (Fig. 10.1) were present in the experimented classroom practices and seemed to be relevant.

During the seminar, the teachers were quite critical of two principal aspects of the classroom experiences. First, they regretted that the assessment procedures they had tried out did not allow them to gather any information about ways in which the groups sometimes did not function well; they felt that such information could be useful for formative interventions aimed at regulating learning progress. We took advantage of this observation to initiate a discussion about the role of disagreements between students while carrying out both the task and the group self-assessment: By which means would it be possible for the students to resolve these disagreements? Is it always necessary to come to an agreement? The research group finally considered that this aspect deserved further exploration through new classroom experiences, in particular to obtain a better understanding of the potential interactive regulations between students in CAfL. The second aspect concerned the teachers’ disappointment about most of the group work products (the students’ texts). Although the teachers were interested in the interactional processes between students in CAfL, they nevertheless kept an eye on the academic product about which they formulated their own judgment.

After the exchanges about the first classroom experiences, the group examined some excerpts of peer interactions during group work, prepared by the observing researcher. These excerpts allowed the teachers to discover part of the content of the exchanges between students and to reflect on the potential value of student interactions in CAfL. One teacher stated:

On reading the excerpts, we discover the wealth of interactions between students, which is not easy for us to see directly on the [assessment] tool. We clearly see that the students’ reflections on their own work in the group are included (teacher 3, school 1).

The excerpts of student interactions were especially appreciated by the teachers because they provided access to information which they would not have otherwise been aware of.

During the classroom experiences, some teachers initiated whole-class discussions about the assessments the students had carried out. The research group discussed the importance of whole-class interactions in order to construct shared meaning with the students about the new assessment practices and criteria. Progressively, whole-class discussions were seen as an integral part of the design of CAfL. As one teacher stated, ‘for the young students, the whole-class discussions can be more valuable than to fill in a chart’ (teacher 4, school 1). And in another teacher’s opinion, ‘the tools are too abstract for the students … because it is difficult for them to reflect on what they did, to put that into words, and to argue’ (teacher 1, school 1). Based on the first classroom experiences, it was decided that the assessment criteria to be included in the tools must be co-defined with the students during whole-class discussions in order to be more significant. Consequently, the teachers adopted a new format for the self-assessment tools. The assessment criteria defined in the whole-class discussions would be copied by each group on the assessment format. After completing the task, the students would write an appraisal of the group’s work with respect to each criterion. They would also answer a question about possible disagreements during group work and the assessment process. The teachers’ intention was still to focus on students’ collaboration skills, seen as being at the heart of CAfL.

3.3.3 Third Seminar

Three months have passed since the last seminar, so it was more difficult for the teachers to describe their CAfL classroom experiences. The document prepared by the observing researcher allowed them to rediscover the activities they had proposed to the students. The teachers talked about their experiences of co-definition of assessment criteria during whole-class discussions held before students worked on the academic task. Three or four assessment criteria included in each tool were collectively decided with the students in the different classrooms. Examples were:

-

Everyone expressed his or her opinion.

-

We discussed calmly to make our decisions.

-

There was not only one single leader.

-

Everybody participated actively in the task.

-

We spoke softly and kindly.

-

We talked mostly about the task.

In general, the criteria focused only on the social dimensions of the students’ activity, but a few criteria mentioned the academic task, for instance:

-

We took into account everybody’s ideas to write our text.

-

We discussed about our writing.

Each group of students wrote a shared appraisal for each assessment criterion. After the use of the assessment tool, whole-class discussions were again held to analyze the assessments carried out by the peer groups. In some classes, several groups of students did not function well. Since the peer groups were not always capable of dealing with this on their own, the concerned teachers decided to talk about these problems during the collective discussions held after the activity. Whole-class discussions thus represented a means of potential regulation of the quality of student interactions.

More generally, the teachers started to express more critical reflection about the idea of CAfL: What is the purpose of assessing group interactions in relation to the academic objectives of the task? How should these different levels be interwoven? What are the benefits of collective construction (by students and teacher) of the assessment criteria?

At this point, we called attention once again to the fact that assessment criteria regarding the academic objectives were lacking in the assessment tools. A discussion emerged about the possible lack of coherence between the academic task the students had to carry out (focused on writing) and the criteria included in the tools (focused on collaboration skills without an explicit link to writing). The teachers expressed uncertainty about their choices. As one teacher stated:

We invented things so different from our day-to-day experiences in the classroom. Normally, our main aim in assessment is the product of group work. The assessment of group functioning is generally of secondary importance. (teacher 2, school 1)

After two cycles of classroom experiences and critical discussions about them, the teachers appeared to be ready to adjust their representations. It seemed that they first needed to try out CAfL procedures focusing on social skills before deciding if they could also be used to assess academic learning. The teachers found it relatively easy to envisage CAfL targeting transversal objectives (which do not lead to grades), but they were unsure of its usefulness concerning academic learning. As one teacher stated:

I am not convinced by collaborative assessment with regard to academic learning…. concerning transversal aspects yes, but I am yet to form an opinion with respect to academic aspects. (teacher 3, school 1)

To a certain extent, the teachers found it difficult to entrust the assessment of academic learning to the peer groups and more generally to the students. As a teacher stated, ‘we asked the students to do something that I think is part of the teacher’s job … to play a role which is not their own, so that is not easy’ (teacher 4, school 1). Nevertheless, at the end of the third seminar, the teachers agreed on the need to introduce academic objectives in CAfL procedures, in relation with substantive issues: What is the purpose of collaborative assessment? Does it contribute to the regulation of learning? We noted that these essential questions became significant only after the two cycles of classroom experiences and collective critical reflections. New classroom CAfL practices were planned precisely to explore these questions. The ongoing doctoral research by Morales Villabona will provide results about the outcomes.

4 Discussion

We think that even the most attractive assessment model will be doomed to failure if it cannot adjust to the constraints and practices of the field. Reports on educational innovation show how difficult it is to implement assessment reforms in teachers’ classrooms (e.g., Gilliéron Giroud and Ntamakiliro 2010). Participative and collaborative research approaches seek to forge closer ties between the scientific and professional communities. The goal is:

To create an intersection between the two working cultures in order to build a common culture, derived from this process of mediation, where knowledge is constructed in collaboration and takes into account both the constraints and the resources of the two worlds, that of research and that of practice. (Desgagné 1997, p. 383, our translation)

The challenge for researchers is to be able to create conditions for integrating teachers’ viewpoints (and the contexts in which teachers practice) with their own scientific frameworks of investigation.

Our chapter has shown how a common project was initiated and developed, regarding CAfL practice, which was a new concept for the participating teachers. It was important to identify and address issues that were pragmatically relevant to the teachers in the context of their assessment practices. Starting with these issues, a deeper understanding was gradually co-constructed between teachers and researchers. Tools, as artifacts, played an important role of mediation between the scientific and the professional communities, whether conceptual tools proposed by the researchers or practical tools and data coming from the classrooms. More significantly, the interpretative activity fostered by these tools, in the setting of professional development seminars and classrooms experiences, led to negotiation of collective meanings and potential transformations of practices.

Our project approached professional development seminars alternating with classroom experiences from a situated perspective. In this view, learning is conceptualized as a transformation of the processes of participation in socially organized activities (Lave and Wenger 1991). The research group, as a community of learning, offered structured collaborative activities favorable to teachers’ professional development. The collaborative research project asked the teachers to be ‘boundary crossers’ (Engeström et al. 1995) able to explore new classroom assessment practices both in deep discussions with researchers and in interaction with the students in their classrooms. The challenge for the teachers was to create new practices based on both experiential and conceptual knowledge. For the researchers, the challenge was to strike the right balance between the scientific and the practical worlds and to maintain favorable conditions for co-regulation between them.

From our experience conducting collaborative research projects (this chapter, Mottier Lopez et al. 2010, 2012; Mottier Lopez 2015), several implications for teachers’ professional development can be drawn. In these projects, participants need to develop a shared culture of collaborative inquiry related to their professional concerns. The co-construction of shared values, norms, and collaborative practices takes time. This process seems to go faster when teachers are from the same school, particularly if they are used to working together. In this case, the teachers share a common school culture and specific issues linked to its context. They also have more opportunities to meet outside the formal seminars to pursue professional development projects. There are, however, some advantages of working with teachers coming from several different schools due to opportunities for confronting different practices and school assessment cultures. Exchanges may be richer, leading to expanded collective and critical questioning between participants. But more time is needed in order to build a relationship of trust and to construct shared meanings within the collaborative research group.

The principal limitation of the project presented in this chapter was its rather short duration (three professional development seminars totaling 14 h, plus the intervening classroom experiences) in order to develop effective collaboration between researchers and teachers and initiate new assessment for learning practices. We think that the duration of collaborative research projects is an important factor in fostering the development of new classroom assessment practices. Several successive cycles of alternation between seminars and classroom experiences need to be implemented, as was the case in a project where collaborative research was conducted over a three-year period (Mottier Lopez et al. 2010). Given the substantial involvement of teachers in collaborative research, it is important that the professional development seminars be carried out during school hours with the support of the school administration which provides funding for release time. A crucial condition for the success of this kind of project is that the school authorities adhere to this form of professional development linked to participation in research.

It would be misleading, however, to idealize collaborative research. It appears that some teachers are at ease with individual forms rather than collective, school-based forms of professional development (Gosselin et al. 2014). In terms of educational policy, we think that it is important to design collective projects of professional development that are articulated with courses to which teachers can sign up individually. In a lifelong learning perspective, we believe that it is crucial for school systems to propose various perspectives and activities for supporting teachers’ professional development in assessment.

Notes

- 1.

In the canton of Geneva, the first grade of kindergarten is designated as grade 1. This means that grades 5–8 correspond to grades 3–6 in the K–12 systems in other countries.

- 2.

The journal (L’educateur) is well known by teachers in French-speaking Switzerland.

- 3.

In the curriculum of French-speaking Switzerland, the term ‘transversal’ objectives refers to objectives that are pursued in all disciplines, as contrasted with academic objectives that are specific to a given discipline.

References

Allal, L., & Mottier Lopez, L. (2005). Formative assessment of learning: A review of publications in French. In OCDE (Ed.), Formative assessment: Improving learning in secondary classrooms (pp. 241–264). Paris: OECD.

Allal, L., & Mottier Lopez, L. (2014). Teachers’ professional judgment in the context of collaborative assessment practice. In C. Wyatt-Smith, V. Klenowski, & P. Colbert (Eds.), Designing assessment for quality learning (pp. 151–165). Dordrecht: Springer.

Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory research methods: A Methodological approach in motion [110 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1). http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1801/3334. Accessed January 22, 2015.

Bourassa, M., Bélair, L. M., & Chevalier, J. (2007). Les outils de la recherche participative. Éducation et Francophonie, 23(2), 1–11.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

Desgagné, S. (1997). Le concept de recherche collaborative: L’idée d’un rapprochement entre chercheurs universitaires et praticiens enseignants. Revue des Sciences de l’Education, 23(2), 371–393.

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., & Kärkkäinen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learning and Instruction, 5(4), 319–336.

Gilliéron Giroud, P., & Ntamakiliro, L. (Eds.). (2010). Réformer l’évaluation scolaire: Mission impossible?. Berne: Peter Lang.

Gosselin, M., Viau-Guay, A., & Bourassa, B. (2014). Le développement professionnel dans une perspective constructiviste ou socioconstructiviste: une compréhension conceptuelle pour des implications pratiques. Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le Travail et la Santé, 16(3). http://pistes.revues.org/4009. Accessed July 19, 2015.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lussi Borer, V., & Muller, A. (2014). Quel apport/usage du “voir” pour le “faire” en formation des enseignants du secondaire. In L. Paquay, P. Perrenoud, M. Altet, J. Desjardins, & R. Etienne (Eds.), Travail réel des enseignants et formation: Quelle référence au travail des enseignants dans les objectifs, les dispositifs et les pratiques? (pp. 65–78). Bruxelles: De Boeck.

Morales Villabona, F. (2013). Modélisation d’une évaluation collaborative des apprentissages des élèves: Alternance entre un dispositif de formation et des pratiques en classe à l’école primaire. Canevas de thèse en Sciences de l’éducation, Université de Genève, Suisse.

Mottier Lopez, L. (2015). L’évaluation formative des apprentissages des élèves: Entre innovations, échecs et possibles renouveaux par des recherches participatives. Questions vives, 23. https://questionsvives.revues.org/1692. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Mottier Lopez, L., Borloz, S., Grimm, K., Gros, B., Herbert, C., Methenitis, J., et al. (2010). Les interactions de la régulation entre l’enseignant et ses élèves: Expérience d’une recherche collaborative. In L. Lafortune, S. Fréchette, N. Sorin, P. A. Doudin, & O. Albanese (Eds.), Approches affectives, métacognitives et cognitives de la compréhension (pp. 33–50). Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Mottier Lopez, L., Tessaro, W., Dechamboux, L., & Morales Villabona, F. (2012). La modération sociale: Un dispositif soutenant l’émergence de savoirs négociés sur l’évaluation certificative des apprentissages des élèves. Questions vives, 6, 159–175.

Paillé, P., & Mucchielli, A. (2012). L’analyse qualitative en sciences sociales. Paris: Armand Colin.

Race, P. (2001). A briefing on self, peer and group assessment. York: Learning and Teaching Support Network Generic Centre (Assessment series no. 9).

Reed, E. S. (1996). Encountering the world: Toward an ecological psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Salomon, G. (Ed.). (1993). Distributed cognition: Psychological and educational considerations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schneuwly, B., Dolz-Mestre, J., & Ronveaux, C. (2006). Le synopsis: Un outil pour analyser les objets enseignés. In M.-J. Perrin-Glorian & Y. Reuter (Eds.), Les méthodes de recherche en didactiques: Actes du premier séminaire international sur les méthodes de recherches en didactiques de juin 2005 (pp. 175–189). Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

Vinatier, I., Filliettaz, L., & Kahn, S (Eds.). (2012). Enjeux, formes et rôles des processus collaboratifs entre chercheurs et professionnels de la formation: Pour quelle efficacité. Travail et Apprentissage, 9.

Voigt, J. (1985). Pattern and routines in classroom interaction. Recherches en Didactique des Mathématiques, 6(1), 69–118.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Organization and Orientation of the Seminars and the Collaborative Assessment Experiences in the Teachers’ Classrooms

Appendix: Organization and Orientation of the Seminars and the Collaborative Assessment Experiences in the Teachers’ Classrooms

Seminar 1 (7 h) | Seminar 2 (3 h) | Seminar 3 (4 h) |

|---|---|---|

Discussion of the “contract” between teachers and researchers: professional development goals and research goals | Teachers share their practices, carried out in class and observed by the researcher | Idem |

Teachers’ questions regarding the theme of the seminars: “assessment and student group work”, an assessment for learning | Based on a document prepared by the observing researcher | Idem |

Initial activity Collaborative drafting, in groups of 3, of an article for a professional journal on the theme of the seminars; teachers experience directly the process of collaboration when carrying out a complex task | Discussion of excerpts of interactions between students during group work and when using assessment tools: How do the students collaborate? What conditions appear necessary for collaborative assessment? | Discussion (idem): What is the purpose of assessing group functioning in relation to the academic objectives? How should these different levels be interwoven? What are the contributions of group moments and whole-class moments with regard to collaborative assessment and student learning? |

Discussion of this experience, with reference to concrete examples in relation to the conceptual framework proposed by the researchers: self-assessment (SA) procedures in student group work (Fig. 10.1) | Discussion concerning the assessment tools created by the teachers and their use in class: What is their role? What conditions will allow these tools to be genuinely conducive to collaborative assessment by students? | Discussion (idem): What are the benefits of collective construction (by students and teacher) of the assessment criteria? |

Collective reflection on – assessment criteria (academic objectives/group functioning) – SA at an individual level and at a group level – roles of the classroom teacher depending on his/her intentions Co-construction of shared principles for collaborative assessment procedures in the classroom – ask the students to focus their assessment on social skills and group functioning – encourage the students to construct a shared appraisal during their joint assessments | Refining the questions raised by the participants – What are the role and contributions of whole-class discussions with regard to collaborative assessment and student learning? – What do students refer to when constructing group agreement during the assessment procedure? What are the sources and the modes of resolution of disagreements? – Which criteria should be adopted to support student collaboration? Why and how should students play a greater role in defining the criteria and constructing the tools? | Refining the questions (idem) – Which learning objectives should be the focus of collaborative assessment? Can different types of learning be assessed with the same procedure or tool? – What is the role of the assessment tool? At which point in the activity should it be used? – What is the scope for individual reflection during collaborative assessment? – What time frame should be adopted for collaborative assessment (occasional, continuous, etc.)? – What is the purpose of the collaborative assessment? Does it contribute to regulation of learning? |

Decisions concerning the experiences to be conducted in class Three different academic activities are planned | Decisions concerning the experiences to be conducted in class A single academic activity is planned in all classes (text production) | Decisions concerning the experiences to be conducted in class Idem (text production) |

Activities to be conducted collaboratively by small groups of students | Idem | Idem |

Self-assessment tools, with criteria at both the individual and the group levels, will be finalised outside the seminar by the teachers | One framework for the self-assessment tools in all classes – criteria to be defined interactively with the students, (ensure that criteria make sense to students) – focus on assessment at the group level (not items at an individual level) – an open-ended rubric for “comments” is added | The assessment tool should include academic objectives (in addition to group functioning), while remaining focused at the group level |

Principles – carry out whole-class discussions with the students – work with them on handling possible disagreements within the group | Principles Continue to carry out whole-class discussions linked to assessment – to construct the criteria – to ensure reflection following assessment experiences | |

Outside the seminar, on the teachers’ own initiative The teachers working at the same grade level developed a single tool with the same assessment criteria; the tools differed between the grades (same criteria for individual and group levels in grades 3–4, different criteria in grades 5–6) | Outside the seminar, on the teachers’ own initiative For each of the criteria in the assessment tool negotiated with the class, the appraisal is communicated by open-ended comments written by the group | After the three seminars Additional meetings were held between the teachers and the researcher to define the classroom observations and the interviews to be conducted for longer-term research purposes |

Use of the assessment tool immediately after the academic activity carried out by small groups of students | ||

Classroom observation: some teachers initiated a whole-class discussion about the assessments the students had carried out | Classroom observation: the teachers adopted the role of moderator when defining the criteria with the students, sometimes reformulating proposals and clarifying/regrouping certain proposals |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mottier Lopez, L., Morales Villabona, F. (2016). Teachers’ Professional Development in the Context of Collaborative Research: Toward Practices of Collaborative Assessment for Learning in the Classroom. In: Laveault, D., Allal, L. (eds) Assessment for Learning: Meeting the Challenge of Implementation. The Enabling Power of Assessment, vol 4. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39211-0_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39211-0_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39209-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39211-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)