Abstract

Online learning communities constitute a dynamically evolving field at both levels, research and development in educational practice. This paper reports on the design and the implementation of two online communities with different organizational–functional characteristics, a self-directed (open) community and a semi-structured community. Using in combination of qualitative and social network analysis methods, this investigation revealed important information regarding critical community indicators, i.e. teachers’ engagement and mutual interaction, as well as collaboration and community evolution. The findings indicated that the semi-structured community was very effective and cohesive, since the majority of the participants were very active and self-organized in groups, and they developed strong interrelations among them. On the other hand, the open community turned out to be very centralized, evolving around the coordinator’s initiatives.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Virtual learning communities are generally thought as social structures, authentically developed under a common purpose, with the aim to promote knowledge sharing and continuously support members’ personal development in a specific field. In the context of situated learning, learning communities are based on dynamic and social participation processes, captured in collaborative activities, working artefacts, routines, stories or perceptions that promote participants’ professional development (Barab and Duffy 2000; Lave and Wenger 1991). Therefore, an effective social learning environment (a) is situated and meaningful (not abstract), (b) activates members through their engagement into learning activities, (c) is mutually constructed through personal contribution and interaction with peers who share common interests, (d) refers to relationships that developed through negotiation rather than to objectives related to formal education.

In last decade, the idea of online teacher communities (TC) has received a growing interest among academics, policy makers and educators as an alternative to both isolated manner of work and the traditional teacher professional development approaches (Brouwer et al. 2012; Jackson 2009; Jimoyiannis et al. 2011). TCs create (a) unique conditions for informal learning and (b) a sustainable environment for teacher communication, interaction and collaboration, without temporal or spatial restrictions. Due to their participatory and collaborative affordances, teacher communities are expected to improve teaching and schooling practices, since teachers have the opportunity to collectively examine and study new conceptions of learning, to share educational material, experiences and practices, to create shared views and improve their instructional practices and, finally, to mutually develop meaning towards achieving their professional growth (Delfino et al. 2008; Jackson 2009; Levine and Marcus 2010; Skerrett 2010).

Online communities have been effectively applied to support educational, training and professional development programmes (Baran and Cagiltay 2010; Delfino et al. 2008; Gray and Smyth 2012; Tang and Lam 2014; Vandyck et al. 2012). There are many studies showing that learning communities can improve teaching practices (Jackson 2009; Levine and Marcus 2010; Skerrett 2010) while they can develop a cooperative culture among teachers in everyday school reality (Vescio et al. 2008). However, any online teacher community could not be successful and not every member will benefit from his/her participation. Literature review has shown that teachers’ motivation and commitment to participate, their perceptions of community learning as well as their collaboration and achievements as members of a community are determined by a wide range of factors (Hur and Hara 2007; Hur and Brush 2009). With regard to the technological environments, asynchronous discussion forums (Cilliers 2005; Correia and Davis 2008; Zydney and Seo 2012) and learning management systems (LMS), such as Moodle and Blackboard, were the most popular and widely used tools to support TCs. On the other hand, the rapid growth and diffusion of Web 2.0 tools have led to increased interest about creating dynamic online TCs (Cho et al. 2007; Gray and Smyth 2012; Hou et al. 2010). Therefore, the design, implementation and investigation of online TCs constitute an open research problem in both areas, teacher development and e-Learning as well (Baran and Cagiltay 2010; Jackson 2009; Levine and Marcus 2010; Roth and Lee 2006).

This paper reports on the design, the implementation and the investigation of two teacher communities with different structure, organization and operation. The first was an open community of computer science teachers who were free to undertake their own initiatives and behave freely within the community. The second was a semi-structured teacher community ran in the context of a masters’ degree course entitled “e-Learning and ICT in education,” at the Department of Social and Educational Policy, University of Peloponnese, in Greece. The conceptual and design framework of the two communities is presented in detail. Preliminary findings about teachers’ performance, community indicators and the role of community structure were derived using a combination of qualitative and social network analysis methods . Conclusions are drawn for future research on online teacher communities of learning.

Theoretical and Design Framework

In the context of situated learning (Lave and Wenger 1991), many design features and ideas have been proposed with regard to teacher communities, where members are using tools and educational material, construct their working artefacts, collaborate and support each other, in order to achieve their learning goals and fulfil common needs (Brown and Duguid 1991; Wilson 1995). In a community of learning, each member is willing to offer his knowledge, experience, abilities and creations to the whole community; thus, he can contribute decisively to the establishment of a social learning culture through collective thinking and knowledge sharing among participants (Siemens 2003). In line with Wenger (1998), there are three core dimensions in an online TC which reflect the nature of a learning community:

Group identity : Mutual engagement that bind teachers together in a social entity.

Shared domain : A joint enterprise as understood and continually negotiated by community members.

Shared interactional repertoire : Shared practices, communal resources and beliefs that teachers have developed over time.

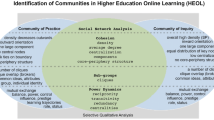

Social interactions in online communities are varied and often complex. Community indicators are directly related to different aspects of community operation and they are expected to be present and evolving over time (Galley et al. 2014; Wenger 1998; Williams et al. 2011). Our research design aimed to better monitor, observe and support successive and iterative teachers’ activities, which are expected to be evolving within the community at three mutually related levels, i.e. personal, group and community level (Tsiotakis and Jimoyiannis 2014).

Therefore, the conceptual framework that supported our design and analysis is built around six interrelated factors-aspects of community, which have a multiplicative effect on each other and, as a whole, they reflect the complexity of members’ learning presence within a teacher community:

Participation: Individuals’ enrolment, self-presentation and ways of attending community activities.

Engagement: Members’ social presence, participation in general discussions and online video conference meetings.

Interaction–reflection : Teachers’ negotiation of ideas and meaning through discussion forums and live journal articles, teachers’ engagement in working groups.

Creativity : Teachers’ content contributions, creation and sharing new knowledge in the community, ability to cocreate new artefacts with others (articles, educational material, original educational scenarios).

Cohesion : Ties among individuals and the community as a whole construct.

Community identity : Cultivating a sense of belonging in the community, common practices taking place within the community and values perceived by individuals in the community.

The Concept of Structure and Community Design

Literature review suggested that community structure is a critical design factor in online teacher communities which has not been studied in a systematic way (Graham 2007; Levine and Marcus 2010). The notion of structure is related to the openness of the community with regard to members’ engagement and contribution constraints. The results presented in this paper refer to a comparative study of two teacher communities, an open community (OC) and a semi-structured community (SC) which used the same operational principles and technological tools. Following the pilot study (Tsiotakis and Jimoyiannis 2013), the community facilitator shaped an ongoing cooperation framework with the aim to support a high level of dialogue, interaction and collaboration among members.

The community platform that used in both communities was designed to provide, in an integrated way, a variety of community tools supporting communication, content sharing, constructive activities and collaboration among participants. From its technological perspective, the platform was structured around the following four core components: LMS unit (Moodle), e-portfolio unit (Mahara), wiki (Mediawiki) and the videoconference system (BigBlueButton) (Tsiotakis and Jimoyiannis 2013).

Table 12.1 presents the TC dimensions analysed along the specific community indicators and the related members’ actions that are expected to be evolving during the community operation. The structure of the community indicators is characterized as high (+) when the particular community activities were mainly determined by the coordinator and they were, more or less, obligatory for the members. On the other hand, it is characterized as low (−) when the expected activities are optional and authentically directed by the participants themselves.

The Study

Objectives and Research Questions

The main objectives of this study were as follows: (a) to extend previous research findings by revealing and analysing critical community indicators, and (b) to shed light into the role of the community structure by revealing the different ways of individual contributions, social interaction and the dynamics of two teacher communities. Based on the theoretical considerations and in accordance to the research objectives, two research questions were addressed:

-

What was the role of community structure and how did it affect teachers’ learning presence and social interaction within the communities? What types of teacher activities were effective?

-

What was the architecture of the two communities? What were the main roles of the teachers recorded?

Participants and context

Two different teacher communities were established in this study. Open community was a homogeneous, domain-oriented community, which ran from October 2011 to March 2012. Computer science teachers in primary and secondary schools were invited by the community facilitator (T) to participate on a voluntary basis, after an open call. Finally, 72 teachers (41 male and 31 female) remained active and exhibited a consistent or periodic presence in the community activities. There were two phases in this self-organized community. In the preparation phase, which lasted 9 weeks, the community facilitator was shaping an ongoing operation framework and the teachers were continually encouraged and supported to keep dialogue, interaction and collaboration active. Following, his role was fading out and the teachers were free to undertake their own initiatives within the community.

The semi-structured community ran from January to June 2013, in the context of a masters’ degree course entitled “e-Learning and ICT in education,” at the Department of Social and Educational Policy, University of Peloponnese, in Greece. Twenty-three students (20 of them were in-service primary and secondary education teachers) attended the course. The community facilitator (T) was acting as e-moderator by setting the context, the expectations and the activities within the community in an emergent and mutually agreed way, in order to achieve a balance between openness and teachers’ constraints. Hence, a minimum level of contributions was requested from each student-teacher: (a) to write one article per month on the journal–blog area presenting a new topic of their choice, and (b) to create and publish a WebQuest scenario in OpenWebQuest platform (OpenWebQuest 2015).

The participant teachers, in both cases, were familiar with digital technologies; however, they had no prior experience of teacher communities and online collaboration tools or platforms. Common activities that teachers were encouraged but free to contribute, both individually and collaboratively, were the following: starting new discussion topics, debating and interchanging ideas, sharing experiences, writing articles in the community blog and commentating on peer contributions, uploading content material, suggesting content resources, creating specific interest groups, undertaking roles and responsibilities, creating original educational scenarios that could be applied in school practice, etc.

Source Data and Social Network Analysis

Data collection and analysis were based on a combination of systematic observation of community online activities along an operation period of 24 weeks. In addition, social network analysis (SNA) methods were used with the aim to reveal students’ engagement, learning presence and individual position within both teacher groups and the whole community. SNA provides a set of algorithms to quantify and give insight into member relations and group dynamics in terms of network structure parameters and graphs, i.e. cohesion, power centrality and betweenness centrality (Jimoyiannis and Angelaina 2012). To determine a starting point for our analysis, we have recorded any isolated incidence of community activities and we established a range of standard statistics. Every member contribution was considered as the unit of analysis (platform enrolment, forum postings, article/blog publications, blog commentaries, wiki page contributions).

Results

Teacher Community Presence

Table 12.2 shows the results representing teachers’ community presence in relation to the community indicators according to our conceptual framework. In both cases, the overall results were quite similar as far as the indicators of participation, engagement and interaction. It is quite clear from the data in Table 12.2 that the majority of the semi-structured community members were very effective. They were actively interacting and collaborating with each other. They created 14 working groups which were not addressed by the tutor but they appeared as the outcome of teachers’ interests and their spontaneous initiatives to collaboratively work with peers in order (a) to study a new educational topic and (b) to design new educational scenarios. In addition, 11 teachers contributed to the wiki activities of new content co-creation.

On the other hand, the majority of the members in the open community (OC) appeared to watch the community activities but they had limited interaction and collaboration with other teachers. Only 17 (out of 72) teachers appeared to be systematically involved into the collaborative activities; 5 teachers contributed to the wiki and 8 teachers published their ideas on the blog. On the other hand, 4 working groups were present in the open community with lower rates of activity and individual contributions. Based on their participation, the OC members were classified into four groups.

The first group includes 10 teachers who sporadically were logging to the community platform without any contribution at all. The second group contains 14 members (observers) who periodically were visiting the community platform, having access to the material and observing discussions; they were not interfering with comments or messages. The third group includes 31 members who regularly attended the events on the platform and participated with few messages in the asynchronous discussions. Finally, 16 teachers were active members and devoted enough time to the community activities, they participated into the teleconference sessions, they contributed to the discussions by posting messages and they were interacting and collaborating with peers to design educational scenarios and share ideas about educational topics of common interest.

Table 12.3 shows the results of the teachers’ activities in the semi-structured community which depict individual engagement and contribution, i.e. (a) active participation in working groups, (b) individual articles published on the community blog, (c) article commentaries received by peers, (d) article views by peers, (e) posts uploaded in the community forum and (f) total time spent in the community platform.

The majority of the teachers in SC were active community members; this finding is also confirmed by the time they spent in the platform. A total of 135 original articles were published on the blog area presenting theoretical and practical educational themes; for example, contemporary pedagogy and ICT, learning design, educational scenarios and practices with ICT. Comprehensive discussions were evolving around the topics above. A total of 647 article commentaries were uploaded by the teachers to share ideas, perceptions or alternative opinions. The number of member views per article is another indicator of intensive social interactions among participants In addition, 21 WebQuests were individually constructed and shared within the community for peer reviewing and commenting.

Social Network Analysis

Cohesion analysis can reveal important information regarding the architecture of a teacher community, i.e. the existence of cliques (subgroups) of community members who were connected internally more than externally. In the semi-structured community, 58 teacher cliques were recorded. The e-portfolio sub-system was adopted by the teachers as the main area around which community activities were evolving; 49 cliques were recorded in e-portfolio. In addition, 4 cliques were in Mediawiki and 5 cliques in the discussion forum concerning general topics. It is important to be pointed that the majority of the cliques (46) included a great number of members, ranging from 7 to 12. This indicates that the SC was a highly cohesive community. In other words, members tended to develop strong interrelations and a wide scope of interactions among them, thus having enhanced opportunities for knowledge sharing and collaborative knowledge construction. The coordinator was present in 13 of the 58 cliques. This is an indicator that SC was self-directed in a great extent and the coordinator’ role was not critical towards influencing participants’ contribution and promoting community operation.

In the open teacher community, on the other hand, we identified 31 cliques. The majority of them included three members, while 8 cliques had 4 teachers and one clique 5 members. The community coordinator had a central role since he was present in 26 cliques. Cohesion analysis confirms the findings of descriptive analysis concerning the factors of participation, engagement and interaction. The OC was not cohesive but a rather static construct. In other words, the type of interactions and the ties among members were very weak.

Power (centrality) analysis is an effective SNA method to measure network activity in terms of community structure as well as the impact each member had with respect to spreading information and influencing others in the community (Jimoyiannis and Angelaina 2012). Figure 12.1 presents the power centrality maps for both communities. In the open community, the coordinator (T) is placed at the centre of the map; he was the most active and influential member in the community (Fig. 12.1a). Teachers M8, M22, M51, M54 and M64 were moderately active members while the majority of the teachers had a marginal (non-visible) contribution. A balanced operation was revealed in the semi-structured community (Fig. 12.1b). The majority of the participants had a significant contribution while the coordinators’ role was not central with regard to the evolution of the community activities. A large group of teachers were placed near the centre (i.e. S3, S10, S22, S15, S4, S6, S7, S8, S17, S19 and S23). They were the most active, influential and powerful members in the community; they had many connections to other powerful participants. On the other hand, as moving to the periphery, teachers were less powerful and important community members. The teachers S9 and S11, for example, had a marginal community contribution.

Figure 12.2 presents the betweenness (intermediation) centrality maps of the two communities. Betweenness centrality highlights the influence each member had as a connector among other teachers. In the open community, the coordinator was the central mediator. The majority of the members, with exception of teachers M8 and M22, had limited contribution and they are placed in the periphery. In SC, teacher S15 was the most effective member towards connecting others. Therefore, he had more control of the interaction and information interchange within the community. Teachers S22, S3, S10, S23, S14, S4 and S7 were also good connectors compared to their peers in the periphery. As an overall view, SC was a very cohesive community; the majority of the participants had significant contribution while only one member (S11) had a marginal role (lurker). In addition, the coordinator (T) had a rather peripheral than decisive role to the community operation.

Conclusions

This paper reported on an investigation concerning the role of community structure by comparatively analysing teachers’ performance in an open and a semi-structured teacher community. With regard to the methodological perspective, the paper proposed a twofold analysis framework based on (a) descriptive analysis of log data extracted from the community platform, (b) social network analysis of teachers’ individual contributions to the various platform subsystems (discussion forums, blog articles, wiki pages, e-portfolio).

Both descriptive and social network analysis revealed important information regarding the dynamics and the cohesion of the communities, the teacher groups developed therein, as well as the role and power each participant had within the communities. Confirming existing research findings (Graham 2007), our results provided supportive evidence that the structured community framework was effective towards promoting teachers’ engagement, interaction, ideas and experiences interchange, collaboration, and knowledge sharing and co-creation, thus developing a live and evolving learning community. In addition, SNA revealed a decentralized teacher community; the facilitator was not the central member of the learning community network while the majority of the participants demonstrated enhanced motivation to be actively engaged into the community activities (uploading articles and postings, supporting dialogue and discussion topics, interchanging ideas, sharing content and resources, cocreating educational material, etc.).

On the other hand, the open community turned out to be very centralized, evolving around the coordinator’s initiatives. Low rates of teachers’ interaction and presence in group activities were recorded. Individuals’ commitment to contribute was not decisive, and the whole community operation was reduced over time. Despite that an open, self-directed design framework would be expected to be more effective and encouraging towards increasing active participation and cooperation among community members (So and Kim 2013), the community structure and the coordinator’s role appeared to be critical success factors, influencing members’ control and motivation to keep the community active.

The proposed analysis framework revealed valuable information regarding critical community indicators, i.e. participation, engagement, interaction, creativity and cohesion, which depict members’ individual contributions, peer interaction and ties, the community structure and teacher groups developed, teacher connections and information flow, group cohesion, as well as the power (influence) each participant had within the community. Therefore, this study offered an integrated framework to track and analyse how an online teacher community was structured and evolved as well as important aspects of members’ presence in the community, i.e. teacher connections and information flow, the power and the influence each participant had within his community.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the existing knowledge by confirming that both openness and constraints are critical factors to effectively organize, support and implement online teacher communities for professional development (Cilliers 2005). Online teacher communities should be, in many senses, self-organized and dynamic; however, a balance between structure and constraint is required to constructively influence the community operation. In addition, the combination of both virtual and physical network aspects seems to be important.

Exploring the role of structure in shaping social learning environments, especially in the field of teacher communities, is an open research problem. Our current efforts are directed towards combining SNA findings with qualitative data from content analysis of teachers’ online discourse (blog articles comments, discussion posts, contributions to the wiki, etc.) and teachers’ interviews. We expect thus to further analyse teachers’ learning presence and knowledge construction as well as common practices and values perceived by individuals within the community. The ultimate goal of this research project was to propose an integrated framework for the design and implementation in practice of effective teacher communities with the affordances to promote professional development of the participants.

References

Barab, S. A., & Duffy, T. (2000). From practice fields to communities of practice. Theoretical foundations of learning environments, 1(1), 25–55.

Baran, Β., & Cagiltay, Κ. (2010). The dynamics of online communities in the activity theory framework. Educational Technology & Society, 13(4), 155–166.

Brouwer, P., Brekelmans, M., Nieuwenhuis, L., & Simons, R.-J. (2012). Fostering teacher community development: A review of design principles and a case study of an innovative interdisciplinary team. Learning Environments Research, 15, 319–344.

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science, 2(1), 40–57.

Cho, H., Gay, G., Davidson, B., & Ingraffea, A. (2007). Social networks, communication styles, and learning performance in a CSCL community. Computers & Education, 49, 309–329.

Cilliers, P. (2005). Complexity, deconstruction and relativism. Theory, Culture and Society, 22(5), 255–267.

Correia, A. P., & Davis, N. (2008). Intersecting communities of practice in distance education: The program team and the online course community. Distance Education, 29(3), 289–306.

Delfino, M., Dettori, G., & Persico, D. (2008). Self regulated learning in virtual communities. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 17(3), 195–205.

Galley, R., Conole, G., & Alevizou, P. (2014). Community indicators: A framework for observing and supporting community activity on Cloudworks. Interactive Learning Environments, 22(3), 373–395.

Graham, P. (2007). Improving teacher effectiveness through structured collaboration: A case study of a Professional Learning Community. Research in Middle Level Education, 31(1), 1–17.

Gray, C., & Smyth, K. (2012). Collaboration creation: Lessons learned from establishing an online professional learning community. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 10(1), 60–75.

Hou, H. T., Chang, K. E., & Ting Sung, Y. (2010). What kinds of knowledge do teachers share on blogs? A quantitative content analysis of teachers’ knowledge sharing on blogs. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(6), 963–967.

Hur, J. W., & Hara, N. (2007). Factors cultivating sustainable online communities for K-12 teacher professional development. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 36(3), 245–268.

Hur, J. W., & Brush, T. E. (2009). Teacher participation in online communities: Why do teachers want to participate in self-generated online communities of K-12 teachers? Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(3), 279–303.

Jackson, T. O. (2009). Towards collective work and responsibility: Sources of support within a freedom school TC. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 1141–1149.

Jimoyiannis, A., & Angelaina, S. (2012). Towards an analysis framework for investigating students’ engagement and learning in educational blogs. Journal of Computer Assisted learning, 28(3), 222–234.

Jimoyiannis, A., Gravani, M., & Karagiorgi, Y. (2011). Teacher professional development through Virtual Campuses: Conceptions of a ‘new’ model. In H. Yang & S. Yuen (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Practices and Outcomes in Virtual Worlds and Environment (pp. 327–347). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levine, T. H., & Marcus, A. S. (2010). How the structure and focus of teachers’ collaborative activities facilitate and constrain teacher learning? Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 389–398.

OpenWebQuest (2015). Wequest Platform. Retrieved July 30 2015, from http://platform.openwebquest.org/en/index.php

Roth, W.-M., & Lee, Y.-J. (2006). Contradictions in theorizing and implementing communities in education. Educational Research Review, 1, 27–40.

Siemens, G. (2003). Learning Ecology, Communities, and Networks extending the classroom. Retrieved October 12 2015 from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/learning_communities.htm

Skerrett, A. (2010). There’s going to be community. There’s going to be knowledge: Designs for learning in a standardised age. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 648–655.

So, K., & Kim, J. (2013). Informal inquiry for professional development among teachers within a self-organized learning community: A case study from South Korea. International Education Studies, 6(3), 105–115.

Tang, E., & Lam, C. (2014). Building an effective online learning community (OLC) in blog-based teaching portfolios. The Internet and Higher Education, 20, 79–85.

Tsiotakis, P., & Jimoyiannis, A. (2013). Developing a Computer Science Teacher Community in Greece: Design framework and implications from the pilot. In Conference Proceedings EDULEARN13 (pp. 70–80).

Tsiotakis, P., & Jimoyiannis, A. (2014). Teachers’ performance within communities of learning: Investigating the role of community structure. In Proceedings of the European Conference in the Applications of Enabling Technologies (ECAET 2014), Glasgow, UK.

Vandyck, I., de Graaff, R., Pilot, A., & Beishuizen, J. (2012). Community building of (student) teachers and a teacher educator in a school-university partnership. Learning Environments Research, 15, 299–318.

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 80–91.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, R., Karousou, R., & Mackness, J. (2011). Emergent learning and learning ecologies in Web 2.0. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(3), 39–59.

Wilson, B. G. (1995). Metaphors for instruction: Why we talk about learning environments. Educational Technology., 35(5), 25–30.

Zydney, J. M., & Seo, K. K. J. (2012). Creating a community of inquiry in online environments: An exploratory study on the effect of a protocol on interactions within asynchronous discussions. Computers & Education, 58(1), 77–87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tsiotakis, P., Jimoyiannis, A. (2017). Investigating the Role of Structure in Online Teachers’ Communities of Learning. In: Anastasiades, P., Zaranis, N. (eds) Research on e-Learning and ICT in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-34127-9_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-34127-9_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-34125-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-34127-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)