Abstract

Tourism events and sport activities have been separately widely analyzed due to the experience value offer, which can be integrated into destination marketing. However, little attention has been paid to the integration of sport as a tourism event that attracts casual sport Food Experiences: The Oldest Social

Food Experiences: The Oldest Socials and serious leisure fans. Therefore, clear orientation to client digital interaction is required, acknowledging that tourism and sport fans behavior are mostly influenced by eWOM and is complex comprehending many elements and a specific social media strategy. The present work offers a first glance at social media strategies in sport tourism events, by analyzing the activity on Facebook and Twitter of fans before, during and after the SATA Rallye Azores, documenting the topic criteria used, the engagement and sophistication achieved and transposing the engagement drivers to the components of the STAR (Storytelling, Triggers, Amusement, and Reaction) model. Results show that to have a content-oriented strategy that maximizes the engagement in social media. However, for the sport event chosen the engagement level found was lower than expected and the STAR model dimensions were completely different from the other social media phenomenon, presenting truly low levels of storytelling.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

This is a unique moment: referred by many as the information age, by others as the digital age, and still others as the globalization era. Regardless of the chosen designator, tourism emerges as a growing activity worldwide making use of the ubiquity of the digital age, the information-intensive nature of the information age and the increasing tourists’ mobility of the globalization era. Thus, the challenge facing any destination or hospitality and tourism firm that wants to be competitive in this market is to leverage their digital presence at a global scale, customizing their offer based on information available.

Hvass and Munar (2012) noticed that the role of online marketing has increased in the tourism industry, and the takeoff of social media following a similar path of what happen in other industries (Tiago and Veríssimo 2014). There has therefore been much discussion of and research on social media and its implications for the tourism and hospitality industries (Zeng and Gerritsen 2014; Goodyear et al. 2014; Munar et al. 2013; Hays et al. 2013; Hvass and Munar 2012).

Looking at tourist behavior, it can be seen that tourist become digital active, as information consumers and as cocreators of contents, sharing and commenting posts, photos and videos (Fotis et al. 2012). As Williams et al. (2015) recall “tourism is an experiential product,” that impels tourist to seek digitally peers opinions about previous experiences when planning a trip. Acknowledging this, Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) suggested that firms could decide to either “participate in this communication, or continue to ignore it.”

This impels us to analyze tourist/fans activity on two social networks regarding a sport tourism event promotes in Azores: SATA Rallye Azores. For that purpose, we used a combination of social network analysis and content analysis on a set of data gathered in Facebook and Twitter, documenting the topic criteria used and the engagement level achieved. The challenge is to validate past conceptual constructions or reshape it in the social media domain.

The present work offers a first glance at social media strategies adopted in local events, by analyzing the activity on Facebook and Twitter of an international sport event: SATA Rallye Azores. This paper is organized as follows. In the first two sections, we review the literature and formulate the researcõh questions. The next section describes the sample and measures used, and then presents the major findings. The findings presentation is accompanied by a discussion of the implications for theory and practice.

Background

Technology has become a baseline of everyday life of billions of people that posts tweets, likes and become fans, and at the same time search, create, and share contents, becoming consumers and creators simultaneously (Tiago et al. 2014). These communications technologies have redefined the tourism industry (Buhalis and Zoge 2007). Both firms and customers have consequently undergone behavioral changes. From a firm’s perspective, technology allows a cost reduction and strengthening the relationship with all stakeholders, permeating contemporary tourism marketing. Above all, these technologies have transformed the culture of purchasing and communication in hospitality and tourism firms, forging digital strategies that are ideally suited to the intangible nature of tourism (Cooper and Hall 2013).

From a tourist’ opinion, tourism is an integrated product with technology catalyzing and enhancing the entire tourism experience (Neuhofer et al. 2013). This involvement reflects the web evolution, from a simple “read-only” format to an “executable” one (Rizzotti and Burkhart 2010). More, the rapid and explosive growth of the Internet, in the last two decades, stimulated social behaviors exchanges and consequently modified human daily activities, habitats, and interactions (Tiago and Veríssimo 2014). These lead tourists to use social media as reliable sources of information, but above all as communities of interest regarding tourism products (Kavoura et al. 2015).

As in other tourism activities, the sport events can be classified in different categories according to the type sport, level of effort, athlete’s commitment and fans involvement with the sport. Recent studies reported that for instance, running events become “serious leisure” in the past 7 years, with tourist choosing their destination based on marathon time, difficulty, and place. In this case the notion of “serious leisure” comprehends that marathoners pass through a “career process” that requires physical efforts, progress and failures, and a strong feeling of identification with the sport (Shipway and Jones 2007). Another example was found in the work of Kane and Zink (2004) regarding kayaking tourists experiences, who were described has been in their own ‘‘social world’’ during the trip, focus on their personal “career progression.” However, not all sports tourism events required a “serious leisure” posture; World Cup or Olympic Games are two mega sport tourism events where most participants level of commitment and effort is quite reduced, since their role is restricted to chairing professional athletes during the game. This led us to question the differences between “serious leisure” and passive sport, from now on referred as “fan casual leisure,” in tourism.

Shipway and Jones (2007) presented the notion of “serious sport tourism” as a combination between “serious leisure” definition of Stebbins (1992, p. 3) and the social identity theory of Thoits and Virshup (1997), where through social identify achievement the tourist is able to experience serious leisure. These authors claimed that “fan casual leisure” is unable to provide the same outcome, driven from the smaller social identify bonds created (Stebbins 2001).

However, when looking at sport-related literature, one common reference found regarding people’s involvement with sports, teams, organizations, and sports athletes are “ego-involvement.” This concept was first presented by Allport in 1945. It explains that involvement is only present when an activity is evaluated from the individual’s perspective, and provides a combination of hedonic value, symbolic value, and a core or central component of their life (Beaton et al. 2011). Thus, even though “serious sport tourism” can offer the individual with a sense of belonging, combined with self-worth and self-esteem enhancement, “fan casual leisure” can get people more overwhelmed than most other activities.

With the social media networks, online and offline experiences tend to bond and social media interactions become a part of the fan event experience. These networks have drastically changed the way fans, sport figures and organizations interact, and communication thrives through social networking (Filo et al. 2015). So, currently reputation and engagement online seems to be key points to any sport-related brand or athlete.

Haven and Vittal (2008) described that user engagement is composed of four “I’s” (p. 3): “Involvement” (“the presence of a person at the various brand touch points”); “Interaction” (“the actions people take while present at those touch points”); “Intimacy” (“the affection or aversion a person holds for a brand”); and “Influence” (“the likelihood a person is to advocate on behalf of the brand”).

In order to make the fan experience unique across social media and other channels, we begin to thinking like fans and assess what they valued. The contents created tend to be the mirrors of their relational commitment and satisfaction, thus monetizing social media can be a help for brands and DMOs that want to promote sport tourism events.

Zeng and Gerritsen (2014) have conducted an exhaustive review of the literature in this domain and identified three domains of influence in social media that merit consideration: (1) as information and communication technologies tools that depend on information technology and firms’ digital marketing strategies; (2) as channels enabling peer-to-peer communication, based on content creation, collaboration, and exchange of content among firms, individuals, and communities; and (3) as a link to constructing a virtual community that affects people’s behaviors.

Social media due to their wide accessibility and ease of use enables tourists to engage in eWOM (Williams et al. 2015). For many, this source is much more reliable than the traditional tourism sources (Duan et al. 2008) and is relevant to support their experience.

So, large online imagined sport communities are created around a sport event or sports figure. The emotional involvement and commitment that occur between sports fans establishes the basis for a community (Kavoura 2014) that shares not only the same values and likes/dislikes, but also similar consumer’ behaviors. Fourie and Santana-Gallego (2011) analyzed mega-sport events impact on tourist arrivals in the host country. These authors found that the results varied in accordance to the type of event, local involvement and the participating countries and whether the event is held during the peak season or off-season. That led us to question if all types of sport events can have the same positive results? And, what make them willing to share and comment experiences?

Framework and Results

Berthon et al. (2012) presented five axioms regarding web evolution and its impacts on consumers and marketing “(1) social media are always a function of the technology, culture, and government of a particular country or context; (2) local events rarely remain local; (3) global events are likely to be (re)interpreted locally; (4) creative consumers’ actions and creations are also dependent on technology, culture, and government; and (5) technology is historically dependent.”. When transposing these axioms’ to the tourism field and considering the findings of Law et al. (2014) is expectable to find that a local event does not remain local and that tourists engagement, actions and creations are equally dependent on technology, culture, and government.

One of the concepts that need to be confirmed in the social media domain is fan classification. Hunt et al. (1999) subdivided fans in several categories according to their geographical, temporal and engagement commitment shown the sport activity. As showed in previous research the interaction on social network related to tourism experience can be much more than brands post, incorporating factual data, opinions, and promoting interactions (Humphreys et al. 2014), for this reason the research approach used combined social network analysis and content analysis. With these considerations in mind, a four-dimensional framework: storytelling, triggers, amusement, and reaction (STAR) is proposed to leverage brands’ and destinations activity on social media. Each dimension will correspond to its weight as found in previous multidimensional analyses of social media contents (Tiago et al. 2015).

Filo et al. (2015) performed a careful review of the literature concerning sports and social media, noticing that most studies focus on Twitter, neglecting the other social networks. As advised by Billings et al. (2014) focusing on Twitter can be deceiving, and further research is needed, including other social network sites and metrics of analysis. Therefore, we focus on Facebook and Twitter, enlarging the field of research.

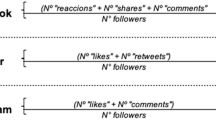

“Fan casual leisure” sports are a popular type of event in Portugal. For this reason, we chose a specific “fan casual leisure” event that occurs in Azores: SATA Rallye Azores, that is celebrating its 50th anniversary. This event occurs in Azores islands and belongs to World Rally Championship (WRC), organized by FIA European Rally Championship, counting with the participation of local, national, and international drivers, that race for 3 days in different types of roads (gravel, asphalt, and mix roads) and counts with numerous spectators. This event is worldwide broadcast by EuroSport and has an official website, Twitter, and Facebook pages, as well as a dedicated app for mobile phones, allowing a global and interactive consumption of the event. Data collection, perform during the weeks before and after the event of 2015, focused on the contents created on two different social networks, Facebook (www.facebook.com) and Twitter (https://twitter.com). Since our aim was to analyze sport tourism behavior in a specific sport event: SATA Rallye Azores, these two social networks were chosen due to their popularity among sport fans of these events. To evaluate the fans composition for the event social structures were analyzed through the use of graph theories. Afterwards the content post was studied and the level of engagement was estimated, allowing estimates of the STAR model.

In light of mounting research regarding to fans typology and considering Hunt et al. (1999) classification, SATA Rallye Azores page fans were analyzed. For this purpose, and based on the network structure found in both social networks, a cluster analysis was performed. Three clusters were found, as showed in Table 1.

Looking at the three clusters and comparing the analysis with the Hunt et al. (1999) fan classification structure, it is apparent that dysfunctional fans do not exist. There are fans based on location but with high activity on the social media pages, was integrated on cluster 3, denoting that this sport event regardless the worldwide coverage, is truly impacting locals.

Analyzing the contents posted and engagement produced in both Twitter and Facebook, the differences are evident and reflect the fact that Twitter has more temporary and devote fans and Facebook has more local and fanatical fans (Fig. 1).

The klout score is a measure used that represents the influence of each user in social media networks. Assessing the klout value for the activity on Twitter of SATA Rallye Azores fans and followers, it is quite evident that their values are smaller than the worldwide average klout score for motorizing sport events

Social media is a game changer. In that sport tourist is in control. For that reason, is necessary in order to evaluate the most suitable elements to use in the social media domain in order to stimulate fans and tourist engagement.

Aspects related to emotional and practical values of content have already been debated in regard to characteristics that would positively lead to fan engagement. As Fig. 2 shows, photos remain the most active triggers of fans’ emotions and actions.

With so much time focused on the messenger, the value of the message itself tends to be devalued. The STAR model reveals that sports fans engagement reflects the capability of the messenger to combine four dimensions: storytelling; triggers; amusement; and reaction (Tiago et al. 2015). The weight found in the multidimensional analysis performed for each of the dimensions was: storytelling 0.1; amusement: 0.37; triggers: 0.33; reaction: 0.2. Both images and links can act as amusement or triggers, depending on if it stimulates an emotional state of mind or simply makes the content memorable. These two dimensions should account for 75 % of the STAR model for the case of SATA Rallye Azores.

As showed in Fig. 3 the outcome in social media of the sport tourism event is quite different from the balance STAR model and this might explain the low levels of nonlocal engagement found.

Final Considerations

The results obtained with the social network analysis suggest that for the case of SATA Rallye Azores the event and the destination influence the composition of the network and its activity, since the new and/or active fans were highly linked to each other based on one of two elements: geographic location and event-information. The quantitative and qualitative analysis conducted allow to validate the STAR model and results achieved reinforce the notion that engagement reflects the messenger’s ability to combine these four dimensions.

Depending on this model, and for the case of SATA Rallye Azores, photos were the most engaging content. Consequently, the trigger dimension received a weight much higher than in previous studies. Besides the images/photos, the content posted that reaches most fans and promotes a higher level of engagement was tied to the launch of a new app related to the event. For this event, the concept of storytelling was not fully explored. In this context, it needs to be understood as a nonstop and mostly improvisations phenomenon, made up of interlinked content that generates a feeling of empathy between fans, drivers, and brands and it is quite relevant to the development of the tourism product experience story. The components of amusement and reaction are related to content valence and the ability to encourage sport tourists to share, comment, and have fun and in this domain the different segments show different preferences in terms of type of content: the local shared with higher intensity photos and links related with the event and with the personal experience, mostly in Facebook; for the other two segments the prevalence was on sport detailed images and local landscapes. All four dimensions are not a requirement, but from their balance use upper levels of engagement can be achieved.

Effective use of social media can generate eWOM that helps to promote and differentiates a destination. For the present case, a deeper analysis of the overall brand awareness of the destiny and the assessment of the SATA Rallye Azores contribution for this awareness is needed it. As a first effort to understand the impact and outcomes of the sport event in social networks, this work leaves the challenge of DMOs and sport event managers to work more effectively the contents and to promote a more dynamic interaction with sport fans/tourists on social media platforms.

References

Beaton, A. A., Funk, D. C., Ridinger, L., & Jordan, J. (2011). Sport involvement: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Sport Management Review, 14(2), 126–140.

Berthon, P. R., Pitt, L. F., Plangger, K., & Shapiro, D. (2012). Marketing meets Web 2.0, social media, and creative consumers: implications for international marketing strategy. Business Horizons.

Billings, A. C., Butterworth, M. L., & Turman, P. D. (2014). Communication and sport: surveying the field: surveying the field: sage publications.

Buhalis, D., & Zoge, M. (2007). The strategic impact of the internet on the tourism industry. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 2007, 481–492.

Cooper, C., & Hall, C. M. (2013). Contemporary tourism: An international approach. Routledge.

Duan, W., Gu, B., & Whinston, A. B. (2008). Do online reviews matter?—An empirical investigation of panel data. Decision Support Systems, 45(4), 1007–1016.

Filo, K., Lock, D., & Karg, A. (2015). Sport and social media research: A review. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 166–181.

Fotis, J., Buhalis, D., & Rossides, N. (2012). Social media use and impact during the holiday travel planning process. Springer-Verlag.

Fourie, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2011). The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tourism Management, 32, 1364–1370.

Goodyear, V. A., Casey, A., & Kirk, D. (2014). Tweet me, message me, like me: using social media to facilitate pedagogical change within an emerging community of practice. Sport, Education and Society, 1–17.

Hays, S., Page, S. J., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media as a destination marketing tool: its use by national tourism organisations. Current Issues in Tourism, 16, 211–239.

Haven, B., & Vittal, S. (2008). Measuring engagement: Four steps to making engagement measurement a reality. In I. Forrester Research (Ed.), Measuring customer engagement (pp. 2–11). Cambridge, USA: Forrester Research.

Humphreys, L., Gill, P., & Krishnamurthy, B. (2014). Twitter: a content analysis of personal information. Information, Communication & Society, 17, 843–857.

Hunt, K. A., Bristol, T., & Bashaw, R. E. (1999). A conceptual approach to classifying sports fans. Journal of Services Marketing, 13, 439–452.

Hvass, K. A., & Munar, A. M. (2012). The takeoff of social media in tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18, 93–103.

Kane, M. J., & Zink, R. (2004). Package adventure tours: Markers in serious leisure careers. Leisure Studies, 23(4), 329–345.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68.

Kavoura, A. (2014). Social media, online imagined communities and communication research. Library Review, 63, 490–504.

Kavoura, A., Stavrianeas, K., & Sotiriadis, M. (2015). The importance of social media on holiday visitors’ choices-the case of Athens, Greece. EuroMed Journal of Business, 10.

Law, R., Buhalis, D., & Cobanoglu, C. (2014). Progress on information and communication technologies in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26, 727–750.

Munar, A. M., Gyimóthy, 2nd, S., Cai, III, L., & Jafari, J. (2013). Tourism social media: transformations in identity, community and culture. Emerald Group Publishing.

Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2013). A typology of technology‐enhanced tourism experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research.

Rizzotti, S., & Burkhart, H. (2010). Usekit: A step towards the executable web 3.0. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web. Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: ACM.

Shipway, R., & Jones, I. (2007). Running away from home: Understanding visitor experiences and behaviour at sport tourism events. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(5), 373–383.

Stebbins, R. A. (1992). Amateurs, professionals, and serious leisure. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). The costs and benefits of hedonism: Some consequences of taking casual leisure seriously. Leisure Studies, 20(4), 305–309.

Tiago, T., & Veríssimo, J. (2014). Digital marketing and social media: Why bother? Business Horizons, 57, 703–708.

Tiago, T., Tiago, F., & Amaral, F. (2014). Restaurant quality or food quality: What matters the more? In: INBAM, ed. International Network of Business and Management Journals. Barcelona.

Tiago, T., Tiago, F., Faria, S., & Couto, J. P. (2015). Who is the better player? Off-field battle on Facebook and Twitter. Business Horizons, Forthcoming.

Thoits, P. A., & Virshup, L. K. (1997). Me’s and we’s. Self and identity: Fundamental issues. pp.106–133.

Williams, N. L., Inversini, A., Buhalis, D., & Ferdinand, N. (2015). Community crosstalk: an exploratory analysis of destination and festival eWOM on Twitter. Journal of Marketing Management, 1–28.

Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27–36.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Faria, S., Tiago, T., Tiago, F., Couto, J.P. (2017). Tourism Events: The SATA Rallye Azores in Facebook and Twitter. In: Kavoura, A., Sakas, D., Tomaras, P. (eds) Strategic Innovative Marketing. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33865-1_55

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33865-1_55

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-33863-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-33865-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)