Abstract

This chapter describes previous research about college students’ financial knowledge as well as approaches to teach financial information to this population. It reviews previous research in these two areas and concludes with ideas for future research. This chapter highlights some of the issues found with measurements of students’ financial knowledge and recommends that larger samples and oversampling of specific students groups may be the key to overcome some of these issues. This chapter also highlights the lack of consensus on ideal models for financial education and points to this shortcoming as indicative of a need for more research to determine the success and failure of existing financial education programs.

The original version of this chapter was revised. An erratum to this chapter can be found at DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_30

An erratum to this chapter can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_30

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

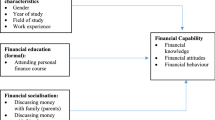

College is the first opportunity for most students to make financial decisions on their own, independent of their parents. The financial knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes that young adults (traditionally between the ages of 18 and 24) may acquire during their tenure at college depend not only on knowledge, skills, and behaviors developed through earlier socialization by family, peers, and early education, but also, to a large extent, on what they observe, learn, and exercise while at college. In turn, this is influenced by their expenditure choices (e.g., influenced by whether they live on- or off-campus), their payment methods (e.g., credit vs. debit cards), whether they are employed, their use and responsibility for education debt and other debt, and even the type of college they attend (e.g., public, private, 2- or 4-year, for-profit).

Students are expected to make decisions regarding educational and living expenses in the form of tuition, books, lab fees, rent, and food. The cost of living poses a significant hurdle for many students. Even those who receive financial aid sufficient to cover tuition and fees may struggle to cover living expenses (College Board, 2014). Students often allocate funds to social activities and material goods that may lead to desired peer approval and group affiliation (Wang & Xiao, 2009).

College students are likely to work part- or full-time to earn money. Balancing work and school takes time, so that some students who work may take longer to complete their studies (Joo, Durband, & Grable, 2008), and thus increase their educational expenditures. Greater financial burdens can lead students to drop out of college, or at a minimum, to reduce their course load to devote more time to paid work (Joo, Grable, & Bagwell, 2003). Students who incur significant debt, work too much, or suffer from financial stress may be more likely to leave college before graduation.

Students have choices in the types of colleges they attend—public, private, or for-profit. Their choices may be constrained financially (Paulsen & St. John, 2002; St. John, Paulsen, & Carter, 2005) by the institution’s cost. The match between a student’s capacity to pay and the institution’s cost affects, at least in part, the student’s persistence. Further, there may be specific financial issues unique to students at each type of institution which require specific financial knowledge.

The financial decisions students make have an important influence on their lives while in college and impact retention (Grable, Law, & Kaus, 2012), productivity, and potentially students’ health (Cude & Kabaci, 2012). College may be a last chance for formal financial education before students become independent adults (Jobst, 2012), with the opportunity to educate students at important decision points in young adulthood (Durband & Britt, 2012) and address concerns about student loans and prevent loan default (Grable et al., 2012). Improving students’ financial knowledge is important if it leads to positive financial behaviors that may improve a student’s quality of life (Xiao, Tang, & Shim, 2009) and build a foundation for lifelong financial well-being.

There are many perspectives from which to view concerns about young, financially inexperienced adults’ ability to successfully navigate financial decisions on their own. These include their financial socialization and the responsibilities of the educational institution as well as the students’ parents to guide and/or restrict students’ choices. However, this chapter focuses on college students’ financial knowledge and approaches to teach financial education to this population. It reviews previous research in these two areas and concludes with ideas for future research.

Previous Research about College Students’ Financial Knowledge

Since Danes and Hira’s article in 1987, the first to report measuring college students’ financial knowledge, more than 50 articles have been published on this topic. Interest has, in fact, increased, with more articles published in 2000 or later than before. Fourteen of these articles reported measuring international college students’ financial knowledge, all but two with a publication date of 2010 or later. From this work, results about the financial knowledge of college students in 14 different countries in addition to the USA have now been published; the countries include Malaysia (Bakar, Masud, & Jusoh 2006; Ibrahim, Harun, & Isa, 2009; Sabri, MacDonald, Hira, & Masud, 2010), Turkey (Akben-Selcuk & Altiok-Yilmaz, 2014; Sarigül, 2014), Australia (Beal & Delpachitra, 2003; Wagland & Taylor, 2009), Brazil (Potrich, Vieira, & Ceretta, 2013), Portugal (Roquette, Laureano, & Botelho 2014), Puerto Rico (Martinez, 2013), and Hungary (Huzdik, Béres, & Németh, 2014; Luksander, Béres, Huzdik, & Németh, 2014).

Research about college students’ financial knowledge has been published in more than 30 different academic journals. In addition, one honors thesis (Baughman, 2014), two master’s theses (Jorgensen, 2007; Micomonaco, 2003), and three dissertations (Gilligan, 2012; Robb, 2007; Woolsey, 2011) have measured students’ financial knowledge. The Journal of Family and Economic Issues has published more articles related to college students’ financial knowledge (6) than any other single journal followed closely by the College Student Journal (5). Overall, 14 articles were published in journals related in some way to finance or personal finance, 11 in journals related to college students and/or young adults, and 10 in journals related to family and consumer sciences.

Three specific issues related to previous surveys of college students’ financial knowledge are described. They are sampling, measurement, and evaluation of the test items.

Sampling

Issue 1: Use of samples that may not be representative of the college student population. Only a handful of articles, including the first (Danes & Hira, 1987) published to measure college students’ financial knowledge, reported using true random samples. In more than 20 studies, a test of financial knowledge was administered to a convenience sample of students in a class (see, for example, Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2006; Shahrabani, 2013) or at another school setting, such as the cafeteria (Micomonaco, 2003; Warwick & Mansfield, 2000). Articles reporting surveys administered online described asking professors to send the survey link to students (Baughman, 2014), using a snowball technique to recruit students (Jorgensen & Savla, 2010), and sending an email to all currently enrolled students at an institution (e.g., Javine, 2013; Robb, 2011).

Issue 2: Low or unreported response rates . Four early studies (Chen & Volpe, 1998, 2002; Danes & Hira, 1987; Markovich & DeVaney, 1997) described mailing surveys to students and reported what are impressive response rates by today’s standards—51.3 % in Chen and Volpe’s research, 45 % in Danes and Hira’s, and 50 % in Markovich and DeVaney’s. More recent studies have posted surveys online; most used convenience samples and thus could not report response rates. However, among the online studies reviewed, only three reported response rates of 40 % or greater (Akben-Selcuk & Altiok-Yilmaz, 2014; Jorgensen & Savla 2010; Xiao, Ahn, Serido, & Shim, 2014). More typical response rates were 9–24 % (LaBorde, Mottner, & Whalley, 2013; Robb, 2007, 2011; Shim, Xiao, Barber, & Lyons, 2009). Baughman (2014) reported reaching only 1.8 % of the undergraduate student population surveyed and Javine’s (2013) response rate was 3.8 %.

Issue 3: Lack of purpose for selection of student populations of interest . Most surveys were aimed at undergraduates in general, although six targeted freshmen (Akben-Selcuk & Altiok-Yilmaz, 2014; Jones, 2005; Lee & Mueller, 2014; Rosacker, Ragothaman, & Gillispie, 2009; Woolsey, 2011; Xiao et al., 2014), one focused on seniors (Markovich & DeVaney, 1997), and one surveyed juniors and seniors (Hanna, Hill, & Perdue, 2010). A few studies (Javine, 2013; Jorgensen, 2007; Smith & Barboza, 2014; Shim et al., 2009) included graduate students in the surveys although the data from those students typically were excluded from the analysis. Makela, Punjavat, and Olson (1993) was the only study reviewed that assessed the financial knowledge of graduate students without including undergraduates. Five studies (Ford & Kent, 2010; Ludlum et al., 2012; Rosacker et al., 2009; Seyedian & Yi, 2011; Wagland & Taylor, 2009) assessed the financial knowledge of business majors only. The selection of student groups seemed motivated by convenience rather than a specific reason to assess the knowledge of the selected groups for a purpose.

Issue 4: Lack of purpose for selection of educational institution of interest . Descriptions of the universities where the students were recruited in previous research were often vague, although most were public institutions described as land-grant or state universities and on a single campus. Eight studies used student samples from more than one state (Chen & Volpe, 1998, 2002; Hancock, Jorgensen, & Swanson, 2013; Jorgensen & Savla, 2010; Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy, 2008; Norvilitis et al., 2006; Rosacker et al., 2009; Sabri et al., 2010). A few studies described the students’ campuses; terms used included metropolitan (Hanna et al., 2010), urban (Norvilitis & MacLean, 2010), and regional (Ford & Kent, 2010). Only one study was conducted at a predominantly black university (Murphy, 2005). Three included community c ollege students (Chen & Volpe, 1998, 2002; Gilligan, 2012), and nine included students at private colleges (Chen & Volpe, 1998, 2002; Goldsmith, Goldsmith, & Heaney, 1997; Jorgensen & Savla, 2010; Ludlum et al., 2012; Norvilitis et al., 2006; Sabri et al., 2010; Warwick & Mansfield, 2000; Woolsey, 2011).

Previous research provides no clear direction about whether student samples from different types of institutions can be combined to increase the number of respondents. Norvilitis et al. (2006) described students’ financial knowledge as “marginally” better at state vs. private universities. However, Jorgensen and Savla (2010), who collected data at “public, private, land grant, research, liberal arts, and undergraduate” universities (p. 469), found very low between-school variances in financial knowledge scores.

Measurement

Measuring college students’ financial knowledge requires knowing what and how to test. Huston (2010) recommended a guideline to measure financial knowledge as 12–20 items with three to five based on each of four content areas :

-

(1)

Money basics (including time value of money, purchasing power, personal financial accounting concepts)

-

(2)

Borrowing (i.e., bringing future resources into the present through the use of credit cards, consumer loans, or mortgages)

-

(3)

Investing (i.e., saving present resources for future use through the use of savings accounts, stocks, bonds, or mutual funds)

-

(4)

Protecting resources (either through insurance products or other risk management techniques).

Issue 1: Lack of comprehensive measures of financial knowledge . By Huston’s (2010) standard, 34 studies measured financial knowledge comprehensively, using measurement instruments that included at least 12 items that tested multiple aspects of personal finance. Nine studies measured knowledge in only one content area: investing (Ford & Kent, 2010; Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2006; Goldsmith et al., 1997; Volpe, Chen, & Pavlicko, 1996), credit (Jones, 2005; Ludlum et al., 2012; Warwick & Mansfield, 2000; Xiao et al., 2014), and student loans (Lee & Mueller, 2014). Most studies measured knowledge objectively but a handful used a self-perceived subjective measure of financial knowledge (Chan, Chau, & Chan, 2012; Shim et al., 2009)—or both (Javine, 2013; Goldsmith et al. 1997; Huzdik et al., 2014; Shim et al., 2009; Smith & Barboza, 2014; Xiao et al., 2014).

Issue 2. Differences in knowledge measures complicate comparison across studies . In most studies, the researchers created their own knowledge test, sometimes pulling questions from other sources but most often not specifying how they constructed the test. The majority of the questions used to measure financial knowledge were based on a previously-used instrument in only 13 of the studies reviewed. The most popular source was the Jump$tart Coalition’s Survey of Personal Financial Literacy among Students (http://www.jumpstart.org/survey.html). Researchers who used this instrument included Baughman (2014); Bongini, Trivellato, and Zanga (2012) who used 13 of the questions; Gilligan (2012) who removed three items for social bias; Lalonde and Schmidt (2009), Norvilitis and MacLean (2010), Norvilitis et al. (2006), Seyedian and Yi (2011), and Shim et al. (2009). Lucey (2005) described the Jump$tart survey as having “moderately high internal consistency overall” (p. 292) but challenged whether the items provide “a complete measure of financial literacy” (p. 292) and described some of the items as socially biased. Other sources of objective financial knowledge questions used in previous research were the Council on Economic Education’s Financial Fitness for Life test (Borodich, Deplazes, Kardash, & Kovzik, 2010), the Debt Management Survey (Lee & Mueller, 2014), and the USA Funds Life Skills Financial Literacy test (Woolsey, 2011).

A few researchers used different approaches to measure college students’ financial knowledge. For example, Borden, Lee, Serido, and Collins’s (2008) measure of knowledge was to ask students whether seven financial management practices were good or bad. Warwick and Mansfield (2000) and Ludlum et al. (2012) asked students about their knowledge of their own credit cards.

Issue 3: Limited evaluation of the quality of the financial knowledge measures. The literature suggests basing assessment of the properties of a measurement instrument on two main test theories: Classical Test Theory, the predominant measurement paradigm in test analysis, and Item Response Theory (Kunovskaya, Cude, & Alexeev, 2014). However, these techniques have rarely been used to analyze financial knowledge tests given to college students. For example, a Cronbach’s alpha indicates whether an instrument is reliable; however, only Jorgensen (2007) and Luksander et al. (2014) reported that statistic—which was 0.77 and 0.63, respectively, both above the recommended cutoff of 0.60. Two others used the statistic to verify the reliability of their financial knowledge instrument. Lee and Mueller (2014) used the alpha to eliminate one of the three subscales in their instrument. Sarigül (2014) evaluated a 30-item assessment instrument and removed seven items based on the Cronbach’s alpha.

More sophisticated techniques based on Item Response Theory can be used to refine results. Bongini et al. (2012) used the Rasch model to identify the most difficult and easiest questions. They described the most difficult as requiring numeracy to calculate cash inflows and outflows. They also reported DIFs (differential item functioning) to evaluate differences in knowledge among subgroups. The DIFs indicated that some items were more difficult for students in different majors while others were more difficult for females than for males.

Factors that Influence College Students’ Financial Knowledge

Given the inconsistencies in the ways previous measures of financial knowledge were constructed and administered, it is not surprising that there is little that can be definitively concluded about previous research. Not all studies reported an overall mean; for example, Danes and Hira (1987) reported means specific to content areas ranging from 48.8 % correct on insurance questions to 81.8 % correct on questions about record keeping. Among those who measured knowledge objectively and reported an overall mean, the percent correct ranged from 34.8 % (Avard, Manton, English, & Walker, 2005; Manton, English, Avard, & Walker, 2006) to 64 % (Jorgensen, 2007) in domestic studies and from 11.8 % (Sabri, MacDonald, Hira, & Masud, 2010) to 65 % (Sarigül, 2014) in international studies.

As for influences on financial knowledge, the greatest consistency in results is about the influences of academic major and gender. At least seven studies reported a positive relationship between being a business major and financial knowledge, including Bongini et al. (2012), who reported the relationship was positive but specific to the type of knowledge. At least 16 studies examined the relationship of gender to financial knowledge. Only Avard et al. (2005) and Manton et al. (2006), who studied freshmen, reported the relationship was not significant. While most studies found that being male was associated with greater knowledge, Bongini et al. (2012) and Danes and Hira (1987) described the significance of the relationship as inconsistent and Norvilitis et al. (2006), who used the Jump$tart Coalition test, reported that females’ scores were statistically significantly different (and higher) than males’ scores.

The relationship between class rank and knowledge was tested in at least eight studies and a positive relationship was reported by most; only Sabri et al. (2010), who surveyed students in Malaysia, did not find a significant relationship. Researchers also have found a positive relationship between employment or work experience and financial knowledge (Akben-Selcuk & Altiok-Yilmaz, 2014; Beal & Delpachitra, 2003; Chen & Volpe, 1998, 2002; Danes & Hira, 1987; Seyedian & Yi, 2011; Shahrabani, 2013). Researchers, including Chen and Volpe (1998, 2002), Jones (2005), Micomonaco (2003), Murphy (2005), and Robb (2007), have consistently reported a link between knowledge and ethnicity and higher financial knowledge scores for whites than for non-white college students.

There is much less evidence about the relationship between other variables examined and financial knowledge. Akben-Selcuk and Altiok-Yilmaz (2014), Chen and Volpe (1998, 2002), Danes and Hira (1987), and LaBorde et al. (2013) reported a positive relationship with age although Danes and Hira described that relationship as specific to insurance and loans. In contrast, Goldsmith et al. (1997) did not find a significant relationship between age and financial knowledge among college students.

Akben-Selcuk and Altiok-Yilmaz (2014) reported a significant relationship between not living at home and financial knowledge. Students who lived off-campus had greater financial knowledge about credit cards and loans in Danes and Hira’s (1987) research and scored higher on the more comprehensive measure that Sabri et al. (2010) used. In contrast, Sarigül (2014) did not find a significant relationship between residence and financial knowledge.

Beal and Delpachitra (2003) reported a positive and significant relationship between income and financial knowledge. Danes and Hira (1987) reported that income was positively related with knowledge about insurance.

Three studies (Akben-Selcuk & Altiok-Yilmaz, 2014; Goldsmith et al., 1997; Smith & Barboza, 2014) reported no relationship between financial knowledge and college students’ GPA. Lalonde and Schmidt (2009) described a significant and positive relationship between self-reported SAT scores and financial knowledge.

Four studies (Akben-Selcuk & Altiok-Yilmaz, 2014; Murphy, 2005; Sabri et al., 2010; Sarigül, 2014) described a positive relationship between parental education and financial knowledge but in Robb’s (2007) research the relationship was not significant. Akben-Selcuk and Altiok-Yilmaz (2014) and Sabri et al. (2010) reported that talking with parents about finances was positively related with students’ financial knowledge.

In Danes and Hira’s (1987) research, being married was positively related to financial knowledge in all areas except record keeping. Robb (2007) reported a positive relationship between college students’ financial independence and financial knowledge.

In research by Avard et al. (2005), Manton et al. (2006), and Lalonde and Schmidt (2009), there was no relationship between financial knowledge and completing a business, economics, or personal finance course. Only Shahrabani (2013), who surveyed students in Israel, found a positive relationship between having completed a business/economics course and financial knowledge. However, researchers have found relationships between financial knowledge and behaviors (owning a savings account – Sabri et al., 2010; having credit cards – Lalonde & Schmidt, 2009).

Previous Research About College Student Financial Education Programs

The term “financial education” has been used interchangeably with “financial literacy education” (Mandell & Klein, 2009; Norgel, Hauer, Landgren, & Kloos, 2009; Vitt et al., 2000; Willis, 2009), “personal financial education” (Hogarth, 2006; Huston, 2010), and “personal finance education” (PACFL, 2008). The term “financial education” can be quite broad, encompassing issues in economics and how decisions are impacted by economic conditions, or it can be narrow, focusing directly on one or only a few aspects of personal financial management. Financial education programs generally operate with the assumption that improving knowledge about personal finance leads to wiser financial decisions.

Some researchers have opined that the deficiency in the financial knowledge of college students is a direct result of the lack of financial education programs in the college curricula (Chen & Volpe, 2002; Cude et al., 2006a; Durband & Britt, 2012; Grable et al., 2012; Jobst, 2012; Norvilitis & Santa Maria, 2002). Some have called on colleges and universities to offer financial education programs as the vehicle to improve financial knowledge among students and help them avoid the pitfalls of poor financial decisions before and after graduation from college (Bianco & Bosco, 2002; Cude et al., 2006a; Cunningham, 2001; Harnisch, 2010; Hayhoe, Leach, Allen, & Edwards, 2005; Hayhoe, Leach, & Turner, 1999; Jones, 2005; Kazar & Yang, 2009; Lyons, 2004a; Peng, Bartholomae, Fox, & Cravener, 2007).

Financial Education Programs

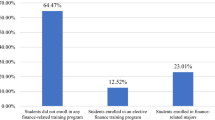

Researchers have found that relatively few colleges and universities offer financial education programs for students (Crain, 2013; Danns, 2014; Grable et al., 2012; Student Lending Analytics, 2008). Student Lending Analytics (2008) reported that 39 % of the colleges and universities in their survey provided a financial education program with financial aid administrators claiming responsibility for most (89 %) of the programs.

Despite the paucity of financial education programs on college campuses, researchers have investigated the nature and design of implemented programs. Researchers providing broad overviews of such programs include Cude and Kabaci (2012), Cude, Lyons, Lawrence, and the American Council on Consumer Interests Consumer Education Committee (2006b), Danns (2014), Grable et al. (2012), and Vitt et al. (2000). Others focused on specific aspects of college-based programs such as delivery methods (Dempere, Griffin, & Camp, 2010; Goetz, Cude, Nielsen, Chatterjee, & Mimura, 2011); program content (Goetz & Palmer, 2012); program staffing issues (Britt, Halley, & Durband, 2012; Halley, Durband, & Britt, 2012); and marketing strategies of programs (Bell, McGarraugh, & De’Armond, 2012).

Four specific issues related to prior research of college financial education programs are reported here. They are models of financial education programs, program delivery mechanisms, program content, and effectiveness of financial education programs and mechanisms.

Issue 1: Lack of consensus on effective models of financial education programs. Cude et al. (2006b) described four general models—financial education/counseling centers, peer-to-peer programs, programs delivered by financial professionals, and distance learning programs. Danns (2014) also identified four organizational models for financial education programs in state colleges and universities—academic, full-fledged money management center, branch, and seed program. Grable et al. (2012), while not specifically categorizing models, explained that financial education programs may be contracted out to third parties, delivered by counseling staff and peer counselors, or delivered through an academic unit.

Issue 2: Students’ differing preferences for program delivery mechanisms . Researchers who studied the mechanisms or methods used by colleges to deliver financial education programs (Cude et al., 2006b; Danns, 2014; Dempere et al., 2010; Grable et al., 2012) found colleges are utilizing a number of delivery mechanisms including credit and non-credit in-class personal finance courses, freshman orientation, telephone sessions, live web counseling, seminars, peer-to-peer and other counseling sessions, workshops, radio programs, flyers, pre-packaged DVD/CDs, blogs, podcasts, videos, email messages, single event activities, pre-packaged online courses, interactive activities, and small group discussions.

Some researchers have examined students’ preferences for specific delivery mechanisms that best serve their financial education needs (Cude et al., 2006a; Danns, 2014; Dempere et al., 2010; Goetz et al., 2011; Lyons, 2004b; Lyons & Hunt, 2003; Sallie 2009) but reached no clear-cut conclusions. In Sallie Mae’s (2009) research, a majority of undergraduate students preferred in-person financial education programs, including classroom sessions, over self-directed or passive financial educational methods. In contrast, financially at-risk students in Lyons’ (2004a) survey preferred online financial information while in Cude et al.’s (2006a) research, students preferred informative websites, financial education centers on campus, workshops, and formal classes. Dempere et al. (2010) found that students wanted a wide variety of delivery methods including formal classroom sessions, one-to-one counseling sessions, workshops, seminars, email tip-sheets, and online tutorials. Goetz et al. (2011) reported that students were interested in online resources and workshops, and, to a lesser degree, a financial counseling center. Students in Danns’ (2014) focus groups showed an overwhelming preference for an in-class personal finance course although some wanted workshops and seminars. Community college students preferred one-on-one discussions or counseling sessions, small group settings, and presentations from financial professionals in Lyons and Hunt’s (2003) research.

Issue 3: Lack of consensus on program content . Cude and Kabaci (2012) explained that there is limited consensus about how to design effective financial education programs on college campuses and by extension what program content should be offered. Some researchers have identified the content areas that colleges currently offer (Danns, 2014; Grable et al., 2012) while others have offered opinions about what should be offered. Jones (2005), Kazar and Yang (2009), and the PACFL (2008) argued that effective financial education programs should be comprehensive and multi-faceted and meet the needs of all students. Others have recommended that financial education programs should address students’ specific needs (Hayhoe et al., 1999; Lyons, 2004a). Lyons (2004a) argued that some groups of financially at-risk students (i.e., students from low- to middle-income families, financially independent students, and minorities) are likely to have specific financial education needs and that financial education programs and services should be tailored to meet these needs. The 2008 Higher Education Act requires colleges that run federal TRIO programs to connect disadvantaged students who participate in the programs with financial counseling (Supiano, 2008). Some researchers have argued for specific training such as investment education (Peng et al., 2007; Volpe et al., 1996). Goetz and Palmer (2012) argued for a more holistic approach to financial education content including financial goal development, money relationships, cash flow planning/budgeting, establishing and improving credit, managing debt, saving and investing, tax education, job selection, planning for expenses after college, and premarital financial counseling.

Kabaci (2012) conducted a Delphi study with 36 experts to identify the personal finance core concepts and competencies that undergraduate college students as a whole, undergraduate loan recipients, and first-generation undergraduates should possess. The personal finance concepts that were identified as important for undergraduate college students included borrowing, budgeting, financial services, saving, student financial aid, insurance, and consumer protection. In addition, 140 personal finance competencies gained consensus by panel members.

Little research has been conducted to identify personal finance concepts that are important from the perspective of the college students themselves. Dempere et al. (2010) reported that a higher percentage of students were interested in learning more about saving/budgeting, paying for college/financial aid, and debt reduction/management than about retirement, investment, insurance, and tax planning.

Issue 4: Efficacy and effectiveness of programs and delivery methods. One of the biggest challenges in measuring the efficacy of financial education programs is that program content varies greatly. This may be due, in part, to the fact that financial education programs vary by school and by department. Some programs emerge from academic units and others are operated by student services or financial aid departments. Still, researchers have examined the effectiveness of delivery methods by comparing two or more delivery methods and single methods. Maurer and Lee (2011) reported similar learning gains from traditional classroom instruction and peer-led financial counseling but pointed to the need for further investigation. Lyons (2004b) found short workshops and small group settings to be effective methods.

Other researchers assessed the effectiveness of single delivery methods, including seminars (Borden et al., 2008); for-credit personal finance courses (Cude, Kunovskaya, Kabaci, & Henry, 2013; Gross, Ingham, & Matasar, 2005); workshops (Rosacker et al., 2009); and online Financial literacyfinancial literacy courses (Woolsey, 2011). Mandell (2009) suggested that the length of a course may play a significant role in effectiveness of financial education after finding that students who took a semester-length course in money management or personal finance were more financially literate than those who had taken only a portion of a course.

Directions for Future Research: Gaps in College Student Financial Knowledge and Financial Education Research

Assessing College Students’ Financial Knowledge

Future researchers who wish to assess college students’ financial knowledge should be guided by the issues addressed in the earlier section of the chapter. Large samples selected systematically and purposefully would improve the quality of future research. For example, if there is value in learning more about knowledge differences between freshmen and seniors or between private and public college students, then random samples purposively collected with the research question in mind are needed. Achieving response rates greater than 50 % is challenging among college student populations (Porter & Whitcomb, 2003) and lower academic ability and male students as well as students of color are typically underrepresented in the responses (Porter & Umbach, 2006). To overcome these issues, larger samples and oversampling of specific demographic groups are recommended. Perhaps most importantly, consensus is needed about personal finance knowledge essential to college students or specific groups of students. With that consensus, a test can be written that includes three to five items for each content area. Ideally, such a test would be piloted and the data subjected to statistical tests based on Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory to select items that provide the most useful information about students’ financial knowledge. With a standardized test given to different student groups, researchers then can conduct analyses more confidently to identify factors that explain differences in students’ financial knowledge.

Designing College Student Financial Education Programs

Future research is needed to further explore issues and opportunities associated with financial education on college campuses. The issues addressed earlier in the chapter are significant. For example, the lack of consensus about ideal models of financial education indicates that more study is needed to determine the opportunities and weaknesses that each presents.

Research is just beginning to systematically explore the personal finance concepts and competencies deemed most important for college students in general, as well as for specific groups such as those with student education loans. Future efforts should continue to work to gain consensus among researchers, administrators, and educators to build better financial education programs for all students. In addition, additional research that examines the issue from the perspective of college students, or specific groups of college students, is needed. Financial education programs are likely more effective when they address concerns that are of immediate relevance to the students themselves.

There is limited research about the financial knowledge and personal financial education needs of the varied types of students that are entering colleges at this time. Harnisch (2010) pointed to rapid changes in the college landscape and outlined that today’s students are more diverse than ever. Research about student financial education needs has failed to keep pace with this changing landscape.

There is a huge gap in our understanding of the financial issues and hence the education needs of non-traditional students, including military veterans, who may enter college with pressing financial problems and obligations including credit card debt, home loans, school- and college-age children, loss of jobs, divorce, and loss of wealth. Their financial situation then is compounded if they add student loans to finance their college education. Their previous experiences as well as their more complex financial lives may make their financial education needs quite different from those of traditional students.

Another neglected dimension in financial education research is whether there are differences, and if so what those are, in the needs of students who attend the various types of colleges. Much financial education research emanates from public research universities whose researchers invariably sample and report on behaviors of their own student population. There is a gap in our understanding of the needs of students at other 4-year as well as 2-year state colleges and universities. Increasingly, a sizeable number of enrollees at these institutions are from the minority populations and/or are first-generation college students who may have different financial issues and financial education needs.

About the Authors

Brenda J. Cude, Ph.D., is a professor in the Department of Financial Planning, Housing, and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia. She is the Undergraduate Coordinator and teaches both undergraduate and graduate courses. Her research focuses on college students’ financial knowledge and behaviors.

Donna E. Danns, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Economics in the Mike Cottrell College of Business, University of North Georgia and has taught courses in macroeconomics, microeconomics, global business, consumer economics, and money and banking. She is a former central banker and has held financial management positions in the private sector. Her current research is in the area of personal financial education in colleges and universities.

M.J. Kabaci, Ph.D., is an Instructor at the Montana State University in the Department of Health and Human Development. She teaches courses in the Family Financial Planning graduate program of the Great Plains Interactive Distance Education Alliance. Her research interests focus on the financial literacy of college students.

References

Akben-Selcuk, E., & Altiok-Yilmaz, A. (2014). Financial literacy among Turkish college students: The role of formal education, learning approaches, and parental teaching. Psychological Reports: Employment Psychology and Marketing, 115(2), 351–371.

Avard, S., Manton, E., English, D., & Walker, J. (2005). The financial knowledge of college freshmen. College Student Journal, 39(2), 321–339.

Bakar, E. A., Masud, J., & Jusoh, Z. (2006). Knowledge, attitude and perceptions of university students towards educational loans in Malaysia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 27(4), 692–701.

Baughman, S. T. (2014). The current state of financial literacy of University of Arkansas students: 2014. Honors Thesis. Sam Walton College of Business, University of Arkansas.

Beal, D. J., & Delpachitra, S. B. (2003). Financial literacy among Australian university students. Economic Papers, 22(1), 65–78.

Bell, M. M., McGarraugh, J., & De’Armond, D. D. (2012). Marketing strategies for financial education programs. In D. B. Durband & S. L. Britt (Eds.), Student financial literacy: Campus-based program development (pp. 79–88). New York: Springer Science.

Bianco, C. A., & Bosco, S. M. (2002). Ethical issues in credit card solicitation of college students – The responsibilities of credit card issuers, higher education, and students. Teaching Business Ethics, 6(1), 45–62.

Bongini, P., Trivellato, P., & Zenga, M. (2012). Measuring financial literacy among students: An application of Rasch analysis. Electronic Journal of Applied Statistical Analysis, 5(3), 425–430.

Borden, L. M., Lee, S. A., Serido, J., & Collins, D. (2008). Changing college students’ financial knowledge, attitudes, and behavior through seminar participation. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(1), 23–40.

Borodich, S., Deplazes, S., Kardash, N., & Kovzik, A. (2010). How financially literate are high school and college students? The cases of the United States, Belarus, and Japan. Proceedings of the Academy for Economics and Economic Education, 13(1), 12–16.

Britt, S. L., Halley, R. E., & Durband, D. B. (2012). Training and development of financial education program staff. In D. B. Durband & S. L. Britt (Eds.), Student financial literacy: Campus-based program development (pp. 37–56). New York: Springer Science.

Chan, S. F., Chau, A. W.-L., & Chan, K. Y.-K. (2012). Financial knowledge and aptitudes: Impacts on college students’ financial well-being. College Student Journal, 46(1), 114–132.

Chen, H., & Volpe, R. P. (1998). An analysis of personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review, 72(2), 107–128.

Chen, H., & Volpe, R. P. (2002). Gender differences in personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review, 11(3), 289–307.

College Board. (2014). Trends in higher education. Retrieved from http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/introduction

Crain, S. (2013). Are universities improving student financial literacy? A study of general education curriculum. Journal of Financial Education, 39(1/2), 1–18.

Cude, B., Lyons, A., & the American Council on Consumer Interests Consumer Education Committee. (2006b). Get financially fit: A financial education toolkit for college campuses. Columbus, MO: American Council on Consumer Interests.

Cude, B., & Kabaci, M. J. (2012). Financial education for college students. In D. Lambdin (Ed.), Consumer knowledge and financial decisions (pp. 49–66). New York: Springer Science.

Cude, B. J., Kunovskaya, I., Kabaci, M. J., & Henry, T. (2013). Assessing changes in the financial knowledge of college seniors. Consumer Interests Annual, 59. Retrieved from http://www.consumerinterests.org/cia2013

Cude, B. J., Lawrence, F., Metzger, K., LeJeune, E., Marks, L., Machtmes, K., & Lyons, A. (2006a). College students and financial literacy: What they know and what we need to learn? In B. Cude (Ed.), Proceedings of the Eastern Family Economics Resource Management Association Annual Conference (pp. 102–109). Retrieved from http://mrupured.myweb.uga.edu/conf/22.pdf

Cunningham, J. (2001). College student credit card usage and the need for on-campus financial counseling and planning services. Undergraduate Research Journal for the Human Sciences. Retrieved from http://www.kon.org/urc/cunningham.html

Danes, S. M., & Hira, T. K. (1987). Money management knowledge of college students. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 17(1), 4–16.

Danns, D. (2014). Financial education in state colleges and universities: A study of program offerings and students’ needs. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Georgia. Retrieved from Open Access Theses and Dissertations https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/danns_donna_e_201405_phd.pdf

Dempere, J. M., Griffin, R., & Camp, P. (2010). Student credit card usage and the perceived importance of financial literacy education. Journal of the Academy of Business Education, 11, 1–12.

Durband, D. B., & Britt, S. L. (2012). The case for financial education programs. In D. B. Durband & S. L. Britt (Eds.), Student financial literacy: Campus-based program development (pp. 1–8). New York: Springer Science.

Ford, M. W., & Kent, D. W. (2010). Gender differences in student financial market attitudes and awareness: An exploratory study. Journal of Education for Business, 85, 7–12.

Gilligan, H. L. (2012). An examination of the financial literacy of California college students. Ph.D. Dissertation, College of Education, California State University, Long Beach.

Goetz, J., Cude, B. J., Nielsen, R., Chatterjee, S., & Mimura, Y. (2011). College-based personal finance education: Student interest in three delivery methods. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(1), 61–76.

Goetz, J., & Palmer, L. (2012). Content and delivery in financial education programs. In D. B. Durband & S. L. Britt (Eds.), Student financial literacy: Campus-based program development (pp. 65–78). New York: Springer Science.

Goldsmith, R. E., & Goldsmith, E. C. (2006). The effects of investment education on gender differences in financial knowledge. Journal of Personal Finance, 5(2), 55–69.

Goldsmith, R. E., Goldsmith, E. C., & Heaney, J.-G. (1997). Sex differences in financial knowledge: A replication and extension. Psychological Reports, 81, 1169–1170.

Grable, J. E., Law, R., & Kaus, J. (2012). An overview of university financial education programs. In D. B. Durband & S. L. Britt (Eds.), Student financial literacy: Campus-based program development (pp. 9–26). New York: Springer Science.

Gross, K., Ingham, J., & Matasar, R. (2005). Strong palliative, but not a panacea: Results of an experiment teaching students about financial literacy. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 35(2), 7–26.

Halley, R. E., Durband, D. B., & Britt, S. L. (2012). Staffing and recruiting considerations for financial education programs. In D. B. Durband & S. L. Britt (Eds.), Student financial literacy: Campus-based program development (pp. 27–36). New York: Springer Science.

Hancock, A. M., Jorgensen, B. L., & Swanson, M. S. (2013). College students and credit card use: The role of parents, work experience, financial knowledge, and credit card attitudes. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(4), 369–381.

Hanna, M. E., Hill, R. R., & Perdue, G. (2010). School of study and financial literacy. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 11(3), 29–37.

Harnisch, T. (2010). Boosting financial literacy in America: A role for state colleges and universities. Perspectives, Fall, 2010, 1–24.

Hayhoe, C., Leach, L., Allen, M., & Edwards, R. (2005). Credit cards held by college students. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 16(1), 1–10.

Hayhoe, C., Leach, L., & Turner, P. (1999). Discriminating the number of credit cards held by college students using credit and money attitudes. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20, 643–656.

Hogarth, J. (2006, November). Financial education and economic development. Presented at the improving financial literacy international conference, OECD, Paris. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education/37742200.pdf.

Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44, 296–316. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01170.x.

Huzdik, K., Béres, D., & Németh, E. (2014). An empirical study of financial literacy versus risk tolerance among higher education students. Public Finance Quarterly, 4, 444–456.

Ibrahim, D., Harun, R., & Isa, Z. M. (2009). A study on financial literacy on Malaysian degree students. Cross-cultural Communication, 5(4), 51–59.

Javine, V. (2013). Financial knowledge and student loan usage in college students. Financial Services Review, 22, 367–387.

Jobst, V. (2012). Financial literacy education for college students: A course assessment. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 12(2), 119–128.

Jones, J. E. (2005). College students’ knowledge and use of credit. Financial Counseling and Planning, 16(2), 9–16.

Joo, S., Durband, D. B., & Grable, J. (2008). The academic impact of financial stress on college students. Journal of College Student Retention, 10(3), 287–305.

Joo, S., Grable, J. E., & Bagwell, D. C. (2003). Credit card attitudes and behaviors of college students. College Student Journal, 37(3), 405–420.

Jorgensen, B. L. (2007). Financial literacy of college students: Parental and peer influences. Master’s Thesis, Human Development, Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, VA.

Jorgensen, B. L., & Savla, J. (2010). Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of financial socialization. Family Relations, 59, 465–478.

Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy. (2008). Survey of personal financial literacy among students. Retrieved from http://www.jumpstart.org/survey.html

Kabaci, M. J. (2012). Coming to consensus: A Delphi study to identify the personal finance core concepts and competencies for undergraduate college students, undergraduate student education loan recipients, and first-generation undergraduate college students. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Georgia. Retrieved from Open Access Theses and Dissertations https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/kabaci_mary_j_201205_phd.pdf

Kazar, A., & Yang, H. (2009). Challenging higher education to meet today’s need for financial education. The Navigator: Directions and Trends in Higher Education Policy, 3(2), 15–21.

Kunovskaya, I., Cude, B. J., & Alexeev, N. (2014). Evaluation of a financial literacy test using classical test theory and item response theory. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35, 516–531.

LaBorde, P. M., Mottner, S., & Whalley, P. (2013). Personal financial literacy: Perceptions of knowledge, actual knowledge and behavior of college students. Journal of Financial Education, 39(3/4), 1–30.

Lalonde, K., & Schmidt, A. (2009). Credit cards and student interest: A financial literacy survey of college students. Research in Higher Education Journal, 10(pt 1–4), 1–14.

Lee, J., & Mueller, J. A. (2014). Student loan debt literacy: A comparison of first-generation and continuing generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 55(7), 714–719.

Lucey, T. A. (2005). Assessing the reliability and validity of the Jump$tart survey of financial literacy. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 26(2), 283–294.

Ludlum, M., Tilker, K., Ritter, D., Cowart, T., Xu, W., & Smith, B. C. (2012). Financial literacy and credit cards: A multi-campus survey. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7), 25–33.

Luksander, A., Béres, D., Huzdik, K., & Németh, E. (2014). Analysis of the factors that influence the financial literacy of young people studying in higher education. Public Finance Quarterly, 2, 230–241.

Lyons, A. C. (2004a). A profile of financially at-risk college students. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 38(1), 56–80.

Lyons, A. C. (2004b). A qualitative study on providing credit education to college students: Perspective from the experts. Journal of Consumer Education, 22, 9–18.

Lyons, A., & Hunt, J. (2003). The credit practices and financial education needs of community college students. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 14(1), 63–74.

Makela, C. J., Punjavat, T., & Olson, G. I. (1993). Consumers’ credit cards and international students. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 17(2), 173–186.

Mandell, L. (2009). The impact of financial education in high school and college on financial literacy and subsequent financial decision making. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Economic Association, San Francisco, CA.

Mandell, L., & Klein, L. S. (2009). The impact of financial literacy education on subsequent financial behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 20(1), 15–24.

Manton, E. J., English, D. E., Avard, S., & Walker, J. (2006). What college freshmen admit to not knowing about personal finance. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 3(1), 43–54.

Markovich, C. A., & DeVaney, S. A. (1997). College seniors’ personal finance knowledge and practices. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 89, 61–65.

Martinez, G. J. R. (2013). El conocimiento sobre planificación y manejo de las finanzas personales en los estundiantes universitarios (The knowledge about financial planning and personal finance management in university students). Global Conference on Business and Finance Proceedings, 8(2), 1350–1354.

Maurer, T. W., & Lee, S.-A. (2011). Financial education with college students: Comparing peer-led and traditional classroom instruction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 680–689.

Micomonaco, J. P. (2003). Borrowing against the future: Practices, attitudes and knowledge of financial management among college students. Master’s Thesis, Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Murphy, A. J. (2005). Money, money, money: An exploratory study on the financial literacy of black college students. College Student Journal, 39(3), 478–488.

Norgel, E., Hauer, D., Landgren, T., & Kloos, J. R. (2009). Money doesn’t grow on trees: A comprehensive model to address financial literacy education. Retrieved from https://www.noellevitz.com/upload/Student_Retention/RMS/Retention_Success_Journal/RetScssJrnlStCatherineU0909.pdf

Norvilitis, J. M., & MacLean, M. G. (2010). The role of parents in college students’ financial behaviors and attitudes. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31, 55–63.

Norvilitis, J. M., Merwin, M. M., Osberg, T. M., Roehling, P. V., Young, P., & Kamas, M. M. (2006). Personality factors, money attitudes, financial knowledge, and credit-card debt in college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(6), 1395–1413.

Norvilitis, J. M., & Santa Maria, P. (2002). Credit card debt on college campuses: Causes, consequences, and solutions. College Student Journal, 36(3), 356–364.

PACFL. (2008). 2008 Annual Report to the President. Washington, DC: President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy. Retrieved from http://www.treas.gov/offices/domestic-finance/financial-institution/fin-education/council/index.shtml.

Paulsen, M. B., & St. John, E. P. (2002). Social class and college costs: Examining the financial nexus between college choice and persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 73(3), 189–236.

Peng, T. M., Bartholomae, S., Fox, J. J., & Cravener, G. (2007). The impact of personal finance education delivered in high school and college courses. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(2), 265–284.

Porter, S. R., & Umbach, P. D. (2006). Student survey response rates across institutions: Why do they vary? Research in Higher Education, 47(2), 229–247.

Porter, S. R., & Whitcomb, M. E. (2003). The impact of lottery incentives on student survey response rates. Research in Higher Education, 44(4), 389–407.

Potrich, A. C. G., Vieira, K. M., & Ceretta, P. S. (2013). Nível de alfabetização financeira dos estundantes universitários Afinal, o que é relevante? (Level of financial literacy of college students: What is relevant?). Revista Electrônica de Ciência Administrativa, 12(3), 314–333.

Robb, C. A. (2007). College students and credit card use: The effect of personal financial knowledge on debt behavior. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

Robb, C. A. (2011). Financial knowledge and credit card behavior of college students. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 690–698.

Roquette, I. U. A., Laureano, R. M. S., & Botelho, M. C. (2014). Conhecimento financeiro de estudantes universitárias na vertente do crédito. (Financial knowledge of credit among college students). Tourism & Management Studies, 10(Special Issue), 129–139.

Rosacker, K. M., Ragothaman, S., & Gillispie, M. (2009). Financial literacy of freshmen business school students. College Student Journal, 43(2), 391–400.

Sabri, M. F., MacDonald, M., Hira, T. K., & Masud, J. (2010). Childhood consumer experience and the financial literacy of college students in Malaysia. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 38(4), 455–467.

Sallie Mae. (2009). How undergraduate students use credit cards: Sallie Mae’s national study of usage rates and trends 2009. Retrieved from http://www.salliemae.com/NR/rdonlyres/)BD600F1-9377-46EA-AB1F\6061FC763246/10744/SLMCreditCardUsageStudy41309FINAL2.pdf

Sarigül, H. (2014). A survey of financial literacy among university students. The Journal of Accounting and Finance, 64, 207–224.

Seyedian, M., & Yi, T. D. (2011). Improving financial literacy of college students: A cross-sectional analysis. College Student Journal, 45(1), 177–189.

Shahrabani, S. (2013). Financial literacy among Israeli college students. Journal of College Student Development, 54(4), 439–446.

Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 708–723.

Smith, C., & Barboza, G. (2014). The role of trans-generational financial knowledge and self-reported financial literacy on borrowing practices and debt accumulation of college students. Journal of Personal Finance, 13(2), 28–50.

St. John, E. P., Paulsen, M. B., & Carter, D. E. (2005). Diversity, college costs, and postsecondary opportunity: An examination of the financial nexus between college choice and persistence for African Americans and whites. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 545–569.

Student Lending Analytics, LLC. (2008). Student lending analytics flash survey: Financial literacy programs. Retrieved from http://www.studentlendinganalytics.com/images/survey090908.pdf

Supiano, B. (2008). For students, the new kind of literacy is financial: Colleges offer programs in managing money. Chronicle of Higher Education, 55(2), A1–A38.

Vitt, L. A., Anderson, C., Kent, J., Lyter, D. M., Siegenthaler, J. K., & Ward, J. (2000). Personal finance and the rush to competence: Financial literacy education in the U.S. Middleburg, VA: Fannie Mae Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.isfs.org/documents-pdfs/rep-finliteracy.pdf

Volpe, R. P., Chen, H., & Pavlicko, J. J. (1996). Personal investment literacy among college students: A survey. Financial Practice and Education, 6(2), 86–94.

Wagland, S. P., & Taylor, S. T. (2009). When it comes to financial literacy, is gender really an issue? The Australasian Accounting Business & Finance Journal, 3(1), 13–25.

Wang, J., & Xiao, J. J. (2009). Buying behavior, social support and credit card indebtedness of college students. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(1), 2–10.

Warwick, J., & Mansfield, P. (2000). Credit card consumers: College students’ knowledge and attitude. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(7), 617–626.

Willis, L. (2009). Evidence and ideology in assessing the effectiveness of financial literacy education. San Diego Law Review, 46, 415–458.

Woolsey, A. (2011). An analysis of first-year freshmen financial literacy and the effectiveness of an online financial education program at small four-year private universities. Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/92/3492666.html.

Xiao, J. J., Ahn, S. Y., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2014). Earlier financial literacy and later financial behaviors of college students. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(6), 593–601.

Xiao, J. J., Tang, C., & Shim, C. (2009). Acting for happiness: Financial behavior and life satisfaction of college students. Social Indicators Research, 92, 53–68.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cude, B.J., Danns, D., Kabaci, M.J. (2016). Financial Knowledge and Financial Education of College Students. In: Xiao, J. (eds) Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28885-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28887-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)