Abstract

There is a large variability in the personality of suicide attempters, but many personality traits and disorders have been consistently associated with suicidal behavior. In clinical settings, psychiatrists and psychologists must often face high-risk patients with marked personality traits, but they seldom investigate personality features to plan the subsequent treatment. This limitation is due to the difficulty of a reliable assessment of personality, the frequent comorbidity with other mental disorders (including other Axis II disorders), and the lack of know-how to apply this information into targeted interventions. However, researchers are progressively carving the features of personality that interact with each other and with other risk factors, such as life events, to amplify the risk of a suicidal act. In this chapter we will review recent findings and outline the options for intervention that are being opened.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Impulsive aggression

- Borderline

- Personality disorder

- Personality traits

- Suicide attempt

- Suicidal ideation

- Narcissism

- Antisocial behavior

- Psychotherapy

- Treatment

1 Introduction

The personality is the enduring pattern of thoughts and behaviors that distinguish human beings from each other. For about 9–15 % of the population in developed countries (Lenzenweger et al. 2007), personality becomes problematic because it deviates markedly from the cultural background, being pervasive and inflexible from adolescence or early adulthood, and leading to significant impairments or distress. These are the criteria of a personality disorder (PD) according to the current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Some PDs are significantly associated with suicidal ideation, attempted and completed suicide, and high levels in some personality traits are recurrently found in samples of suicidal patients. Indeed, PDs are extremely frequent in clinical samples of psychiatric patients and even more among those becoming suicidal. About one-third of completed suicides according to autopsy studies and three in four suicide attempters could be diagnosed with a PD (Pompili et al. 2004). Considering the personality of patients at risk of suicidal behavior (SB) is important since: (i) PDs are frequently comorbid with other Axis I or Axis II disorders, (ii) the presence of a PD complicates prognosis and treatment response, and (iii) personality traits should inform any assessment of suicidal risk to control for their effect on other risk factors. Inversely, the role of personality is largely mediated by other factors, including comorbid psychopathology but also lifetime interpersonal difficulties or adverse life events (Schneider et al. 2008).

To date, research on risk factors of SB has mainly focused on Axis I mental disorders and sociodemographic features, and only some authors have focused on personality. However, personality features, along with other three dimensions, namely, psychopathology, life events, and suicidal staging, are critical to any model of SB aiming to attain an accurate risk representation (Courtet et al. 2011). For instance, personality features are clearly associated with the risk of repeating a suicide attempt. In a systematic review of the literature, personality traits such as anger/impulsivity, affect dysregulation, or compulsivity/anxiousness, as well as having a PD, were associated with the repetition of suicide attempts (Mendez-Bustos et al. 2013). Of note, although personality is a key element to understand SB, suicide attempters themselves cannot be easily clustered into “personality” groups. The results of studies of clustering are unclear but suggest two main subtypes of personality among attempters: (i) an internalizing subtype, characterized by general negative affect, and (ii) an emotionally dysregulated subtype, close to borderline PD (BPD; (Lopez-Castroman et al. 2015)). These subtypes have also been described as introverted/negativistic/avoidant/dependent/neurotic on the one hand and impulsive/hostile/antisocial on the other hand (Turecki 2005). However, personality features do not seem to differentiate the lethality or severity of suicide attempts in cluster analysis (Lopez-Castroman et al. 2015), which is in keeping with previous research (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2009a).

2 What Personality Traits and Personality Disorders Should We Look for in Patients at Risk of Suicidal Behavior?

The PDs most frequently associated with SB are situated in the so-called DSM-IVFootnote 1 cluster B (emotional/erratic), which includes antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic PDs. These PDs account for the bulk of suicide risk among individuals with significant personality pathology (Ansell et al. 2015). However, the personality traits that increase the risk for suicidal acts are not exclusive of this cluster.

2.1 Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

Recurrent SB is one of the diagnostic criteria of BPD. Although as many as 46–92 % of BPD patients attempt suicide during their lifetime, completed suicide is relatively rare (3–10 %) (Soloff and Chiappetta 2012a). Sixty percent report multiple suicide attempts (Zanarini et al. 2008), and indeed the repetition of suicide attempts, compared to single attempters, is associated with this diagnosis (Forman 2004). Despite their bad reputation, there is evidence of a positive evolution for many BPD patients in the long term (Shea et al. 2002; Tracie Shea et al. 2009; Zanarini et al. 2010), underlining the importance of supportive and preventive interventions in the period of high suicidal risk of SB. In fact, suicidal acts in BPD may help to regulate the emotional response when the individual is confronted to high psychic pain (Paris 2004). However, BPD patients that commit suicide seem to be less prone to psychiatric treatment. A meta-analysis of the literature showed that higher rates of suicide in BPD are associated with short-term rather than long-term follow-up (Pompili et al. 2005).

Developmental models suggest an interaction between life events, particularly early trauma, with the evolution into the symptomatic disorder of BPD and SBs (Hayashi et al. 2015). In a study with 120 BPD patients, those who died by suicide (n = 70) were compared with the rest of the sample (McGirr et al. 2007). BPD suicides had higher levels of Axis I and II comorbidity, novelty seeking, impulsivity, and hostility than survivors, as well as less suicide attempts and psychiatric hospitalizations. The interaction of impulsive and aggressive features and the comorbidity with other cluster B disorders (especially antisocial PD, which is found in 92.5 % of suicides), as well as lower harm avoidance, predicted a fatal outcome in this sample. Another study, the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, followed 431 participants for 10 years while considering the severity and dimensionality of the PDs. According to their results, paranoid, antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and dependent PDs emerged as independent risk factors for ever attempting suicide, but only the severity of BPD was retained in the multivariate model (Ansell et al. 2015). In other words, the common variance underlying multiple PDs that leads to SB may be best reflected by the diagnosis of BPD. Despite these advances, the accurate identification of the more “risky” BPD patients continues to be a challenge in clinical settings.

2.2 Antisocial Personality and Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD)

Antisocial patients behave in an irresponsible, impulsive, abusive, and guiltless manner. Having an ASPD predicts comorbid addictive, psychiatric, and medical problems, as well as high rates of SB, homicides, and accidents. The literature on personality-related suicide risk has mainly been focused on BPD. Accordingly, literature on ASPD and suicide is relatively scarce (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2007). The rate of suicide attempts in individuals diagnosed with ASPD range from 11 % to 42 % (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2007; Zaheer et al. 2008), but up to 72 % of patients with ASPD might attempt suicide (Garvey and Spoden 1980). Suicide attempts in ASPD individuals are usually considered nonserious, with no real intention to die, in order to manipulate others or to act out their frustration, and secondary to interpersonal loss or problems (Garvey and Spoden 1980; Frances et al. 1986). This lack of seriousness may suggest that they have no real intention of killing themselves and that they use suicide attempts to have a secondary gain (e.g., hospital admission) (Pompili et al. 2004). In a military hospital setting, antisocial patients used SB as an alternative channel to alleviating distress (Sayar et al. 2001).

The high rates of suicide attempts among ASPD individuals contrast to the rates of completed suicides (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2007). Suicide rates reported among patients with ASPD vary considerably as most studies use no operationalized criteria (Bronisch 2007), but most studies report rates around 5 % (Miles 1977; Zaheer et al. 2008), which is lower than the 8 % found in BPD in long-term follow-up studies (Bronisch 2007). Frances et al. (1986) hypothesized that the 5 % rate of suicide found in subjects with ASPD could be explained by the presence of a concurrent affective disorder, substance abuse, or other PD (Frances et al. 1986). Therefore, the traditional assumption derived from Cleckley and other classical authors that antisocial individuals could be so self-centered to actually try to kill themselves could be inconsistent with current findings (Lambert 2003).

In any case, ASPD individuals are typically quite refractory to medical treatment but show moderation with advancing age and positive life events, such as marriage or employment, which facilitate socialization (Black 2015). On the contrary, and independently of comorbid Axis I disorders, negative life events (particularly the death of the partner) seem to precede suicidal acts in this population (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2010). Serotonergic dysfunctions are found both in antisocial populations and patients at risk of SB. Interestingly, epigenetic mechanisms may explain the downregulation of serotonergic genes in antisocial offenders (Checknita et al. 2015). Of note, adolescent ASPD has been associated with all the stages of the suicidal process (ideation, attempts, and suicide), and inversely SB among adolescents is very frequently associated with antisocial behaviors according to the results of epidemiological studies (Marttunen et al. 1994). Furthermore, parents with antisocial personality transmit the risk of SBs to their offspring (Santana et al. 2015).

2.3 Histrionism and Histrionic Personality Disorder (HPD)

Histrionism is characterized by an enduring pattern of attention-seeking behavior and extreme emotionality. The concept of HPD arose from the clinical observation of common personality traits among women displaying conversion symptoms. Although it is usually associated to female gender, no gender differences were observed in an epidemiological study in the USA (Grant et al. 2004).

There is little knowledge about the link between SB and HPD. In a geriatric sample of 109 patients, histrionism showed negative correlations with suicidal ideation in the regression analyses (Segal et al. 2012). However, suicide attempts are frequent in people with HPD or histrionic personality traits, either as a way of emotional blackmail to the ones who take care of them or to attract attention from people (Rubio Larrosa 2004). Moreover, hysterical personality traits have been associated with suicide attempts in both women and men (Pretorius et al. 1994). Although some suicide attempts by HPD individuals take place in “a mood, albeit short-lived, of genuine despair,” usually it is clear from the circumstances that suicide attempts are made to coerce someone else into behaving in a way similar to the patient’s liking (Kendell 1983). Indeed, most suicide attempts are precipitated by disturbed relationships with close relatives or sexual partners. Due to their demanding, egocentric behavior and their dependence needs, their interpersonal relationships are characteristically stormy and fragile (Kendell 1983). Thus, it is not surprising that in a recent study with 150 psychiatric inpatients who had engaged in some kind of SB, HPD was a specific risk factor for suicide gestures but not for suicide attempts (García-Nieto et al. 2014). In other words, it is possible that some of the suicide attempts by HPD individuals could be better classified as suicide gestures.

As for completed suicide, HPD seems to be associated with a lower risk at least compared to other cluster B PDs. However, even if histrionic individuals tend to mature with time, some fail to obtain attention, becoming increasingly lonely, depressed, or addicted, which could eventually lead to a fatal outcome (Kendell 1983). Interestingly, one study has found that comorbidity with HPD among BPD patients predicts less lethal suicide attempts (Soloff and Chiappetta 2012a).

2.4 Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD)

NPD is characterized by lack of empathy for others, extreme grandiosity, and extreme self-involvement, among others (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2007). Few studies have investigated the SB of narcissistic patients (Pompili et al. 2004). Kernberg (1993) suggested that NPD or narcissistic personality traits could make an individual vulnerable to SB (Kernberg 1993). This vulnerability could be related to a fragile self-esteem (Perry 1989), which they try to raise through suicidal acts (Ronningstam and Maltsberger 1998). Thus, when we compared suicide attempters in Madrid with different cluster B diagnoses, those with NPD had higher expected lethality, but not higher impulsivity, than those without. Inversely, attempters with ASPD, BDP, or HPD were more impulsive, but did not report more expected lethality, than those without (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2009b). Depressed geriatric patients with narcissistic personality (either disorder or traits) scored higher in suicide risk than non-narcissistic controls in another study (Heisel et al. 2007).

As for suicide, they are more likely to commit suicide than patients without NPD or narcissistic traits, particularly if BPD was also present, according to a 15-year follow-up study of 550 patients in New York (Stone 1989). In a postmortem study with 43 consecutive suicides among Israeli males aged 18–21 years during compulsory military service, the most common Axis II diagnoses were schizoid PD (37.2 %) and NPD (23.3 %) (Apter et al. 1993). In any case, according to the psychological autopsy method, it is an infrequent diagnosis in suicides (Links et al. 2003).

In conclusion, narcissistic traits should be carefully considered when evaluating patients at risk of SB, as patients with these traits may be particularly at risk of making fatal attempts. Individuals who have suffered a “narcissistic injury” might react with rage and envision suicide as a means for retaliating or regaining control and plan more carefully their acts (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2009b). Of note, a recent study has shown that a single question could provide good results to evaluate narcissism (Konrath et al. 2014).

2.5 Impulsive Aggression

Impulsive aggression has been proposed as an endophenotype of risk for SBs related to reactive aggression. A combination of high impulsivity and high aggression is frequent among suicide attempters (Gvion and Apter 2011), but the components of this construct seem to have different effects on the suicidal acts. Although impulsivity is clearly related with making more suicide attempts, its role in the severity of the attempts is less clear (Soloff et al. 2005). The impulsivity of the attempt does not correlate well with the impulsivity of the attempter, and some authors argue that impulsivity as a trait facilitate the exposition to adverse experiences through the lifetime that eventually lead to SB (Anestis et al. 2014). In fact, aggressiveness has shown to be a better predictor of SB than impulsivity or hostility among depressed patients (Keilp et al. 2006). However, as previously stated, there is a well-documented association between impulsive personality traits and lifetime aggression in suicidal subjects (Rujescu and Giegling 2012), and the interaction of both components contributes to suicide completion, at least in BPD (McGirr et al. 2007). The familial transmission of SB appears also to be mediated by impulsive aggression and hostility traits. Indeed, completing a vicious circle, early life adversities (suicidal acts or childhood abuse in the family) are frequently present in the history of suicidal patients with high impulsive aggression levels (Lopez-Castroman et al. 2014). Of note, a gender effect should be considered for personality traits, such as impulsive aggression, with regard to SB. In a case-control study of individuals with major depressive disorder, Dalca et al. (2013) have recently shown that male completers, but not females, were characterized by impulsive aggression compared to controls (Dalca et al. 2013). According to their results, only non-impulsive aggression was part of the suicidal diathesis in females.

2.6 Hostility, Anger, and Other Personality Traits

Hostility and anger are common traits of patients with cluster B disorders, and both are positively related to suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts in adolescents and adults (Ortigo et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2012). Among prisoners, anger and hostility scores differentiate also those who had attempted suicide (Roy et al. 2014). Furthermore, hostility was found to be higher in depressed attempters with siblings concordant for SBs (Brent et al. 2003).

Apart from the abovementioned, many personality features have been related to SB. For instance, irritability, low self-esteem, problematic coping strategies, inability to support stable interpersonal relationships, external locus of control, despair, intense feelings of fault and/or of shame following minimal mistakes, cognitive rigid style, and perfectionism (Blasco-Fontecilla et al. 2007). Within the Five-Factor model, two personality dimensions have been associated with SB: low extraversion and high neuroticism (Ortigo et al. 2009). In a recent study, low positive affect, as well as high aggression, predicted subsequent suicide attempts (during a 6-month follow-up) in adolescent attempters better than any Axis I or II disorder (Yen et al. 2012). Indeed, the authors suggest that affective and behavioral dysregulation, a component of many psychiatric diagnoses, could mediate the risk of new attempts in this high-risk population. Schizotypic personality has also been associated with lifetime suicide attempts. One study suggests that the degree of schizotypy could be associated with the risk of lifetime suicide attempt in patients with schizophrenia (Teraishi et al. 2014).

Finally, it is important to bear in mind the stability of personality traits. Personality traits associated with SB, or “suicidal” traits, show some instability during the lifetime according to long-term follow-up studies. For instance, in the case of BPD, patients have a tendency to be revictimized and re-experiment traumatic situations, but in the long run they acquire better coping skills and see their impulsivity, together with the risk of SBs, decrease (Zanarini et al. 2010). It should be noted that the instability of PDs might in part be due to the limited validity of current diagnostic systems. First, the diagnosis of a PD is made with a heterogeneous combination of persisting traits and transversal symptoms that may disappear with the evolution of the disorder. Secondly, the severity of PDs might not be accurately reflected by current classifications (López-Castromán et al. 2012).

3 Comorbidity with Axis I Disorders

The comorbidity with an Axis I disorder is probably the most important risk factor for suicide among individuals with PDs. This comorbidity characterizes also an important subgroup of suicide attempters who are at particularly high risk of repeated SB (Cheng 1995; Foster et al. 1999; Hawton et al. 2003). Comorbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders is reported in 14 % (Vijayakumar and Rajkumar 1999) to 58 % of all suicide victims (Cheng et al. 1997). Personality traits modify suicide risk differently depending on the underlying Axis I disorder (Schneider et al. 2008). Having a depression and being substance dependent are themselves suicide risk factors. But when they are comorbid with a PD, the risk of suicide goes beyond the simple sum of relative risks (Schneider et al. 2008). This may be particularly true for PDs in clusters B and C. For instance, the comorbidity of BPD and depression increased the number and seriousness of suicide attempts in a sample of inpatients (Soloff et al. 2000). A large population-based survey in Mexico describes multiplicative effects of depressed mood and antisocial problems with regard to death thoughts, suicidal plans, and attempts (Roth et al. 2011). According with a case-control study including 104 depressed males that had completed suicide and 74 living depressed male controls, completers had higher levels of comorbidity with substance use disorders and cluster B PDs, particularly ASPD and BPD (Dumais et al. 2005). The use of substances in BPD impairs the judgment of the patients and enhances the risk for impulsive attempts, which may explain why BPD with substance use disorders show worse suicide-related outcomes (Anestis et al. 2012).

4 Can We Reduce the Suicidal Risk Associated to Personality Disorders or Traits?

We can currently respond positively to this question, although individuals who suffer from PDs are still extremely difficult to treat for various reasons. Firstly, often patients are inobservant and demand treatment only when in stressful circumstances that render their coping abilities completely insufficient. Secondly, treatment of PDs typically involves a prolonged and intensive treatment with involvement of several forms of support. Thirdly, patients with PDs are frequently exposed to life events that trigger the suicidal crises (Yen et al. 2005). Finally, despite the increasing number of therapeutic options, both in psychopharmacology and psychotherapy, there is a paucity of specific treatments for the suicidality of PDs.

Thus, risk reduction in PDs needs to enhance the therapeutic alliance to avoid dropouts and provide a constant, regular, and long-term reference. The triggering effect of oncoming adversities can be anticipated and prevented when working closely with the patients. In this vein, Brodsky et al. (2006) found that the first suicide attempt in depressed BPD patients is commonly an interpersonal crisis (Brodsky et al. 2006). Besides, mental health professionals can focus on specific traits known to carry more risk. For instance, treating aggressive tendencies may reduce the risk for SB through integrative therapies (Zhang et al. 2012). But the first step in treatment is a good assessment. A complete psychiatric evaluation, after assessing for suicide risk and identifying the stage of the suicidal process (ideas, plan, or attempt), should investigate personality traits that are relevant for subsequent treatment. In the case of BPD patients, comorbid antisocial or schizotypal features may heighten suicide risk (Zaheer et al. 2008). Subsequent treatment should combine effective pharmacotherapy to treat comorbid Axis I disorders and relevant symptoms, such as depressed mood and affective lability, and psychotherapy. At the same time, supportive treatment in the context of a suicidal crisis should include all the interventions known to prevent suicide attempts such as 24 h crisis care, follow-up continuity in the days following the suicidal crisis, control of potential suicide means, treatment of comorbid substance use disorders, a policy on how to respond to noncompliant patients, or assertive outreach programs (While et al. 2012).

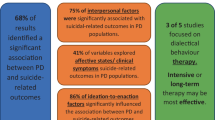

4.1 Psychotherapy

The usual treatment for PDs involves long-term psychotherapy with an experienced therapist. A recent meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials in adolescents has shown that suicidality (including suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm) during follow-up was reduced among adolescents receiving psychological or social interventions compared to controls. Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), followed by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mentalization-based therapy (MBT) showed the largest effect size (Ougrin et al. 2015). However, when suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm were studied separately, these interventions showed no difference with treatment as usual.

DBT is adapted to the features of BPD while focused on reducing self-harm behaviors (Linehan et al. 2012). However, DBT comprises multiple interventions, from individual therapy, to skills training, telephone coaching, and a consultation team. A recent study has found that all of these components actually play a role in the prevention of suicide attempts (Linehan et al. 2015). Interestingly, the decrease in suicide attempts and increase in anger control that is seen in BPD patients who receive DBT is fully mediated by the skills learned in the therapy (Neacsiu et al. 2010). Moreover, a DBT-based program for relatives of BPD patients, which provided general knowledge about SB and training for interpersonal skills, showed some promise of improving the family-patient relationship (Rajalin et al. 2009). However, ASPD is a risk factor for premature termination of DBT (Kröger et al. 2014).

Other structured treatments, such as transference-focused psychotherapy, have proved their utility in the reduction of suicidality compared to supportive therapies (Clarkin et al. 2007). Recently, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), an intervention designed to increase psychological flexibility, has been found useful to reduce psychic pain, depression scores, and suicidal ideation in a small sample of suicide attempters, many of which had a BPD (Ducasse et al. 2014). Of note, a recent review has compared the results of trials investigating the effectiveness of diverse types of psychotherapy to reduce SBs among BPD patients. The authors suggest that a more intense or long was not necessarily associated with a greater reduction of suicidal acts (Davidson and Tran 2014).

An interesting study examined through psychological autopsy the suicide victims that were receiving individual psychotherapy 3 months prior to their death. The authors found that nine out of 16 cases fulfilled criteria for a personality disorder, and they were frequently comorbid with a mood disorder (Pallaskorpi et al. 2005). Of note, those 16 patients were the only suicide completers receiving regular psychotherapy among 1,397 suicides from the Finnish national registry (1.1 % of the sample).

4.2 Pharmacotherapy

Psychotropic drugs are commonly used to treat some of the personality features that are associated with SB in clinical settings worldwide, such as impulsivity, anger, or mood shifts. The symptomatic relief provided by antidepressants, neuroleptics, or mood stabilizers appears to reduce the risk of suicidal acts for some patients. Kolla et al. (2008) have reviewed the psychopharmacological interventions for the management of SB in BPD (Kolla et al. 2008). However, the evidence for the use of psychotropic medication to specifically reduce SBs among patients with PDs is still inconclusive (Saunders and Hawton 2009). The known or potential antisuicidal effect of some medications (especially lithium and clozapine) deserves the development of future trials.

4.3 Hospitalization vs. Ambulatory Treatment

Beyond the preventive and supportive strategies that have been developed for acutely suicidal patients, chronically suicidal patients, such as BPD patients, need long-term interventions in ambulatory settings. Some authors advise against hospitalizing BPD patients in the management of self-harm because there is no evidence that it may prevent completion and it may paradoxically induce the patients to use self-harm behaviors help to become chronic (Paris 2004), but in case of acute suicidal crises inpatient treatment may be needed to prevent fatal outcomes (Oldham 2006).

Importantly, the targets of treatment should change over time. A recent study with 90 BPD patients has shown how acute stressors (depression) predict suicide attempts only during a year, while poor psychosocial functioning has long-term effects on suicide risk (Soloff and Chiappetta 2012b). Moreover, the authors underline the importance of rehabilitation treatments to prevent the poor psychosocial outcomes among these patients. We should also keep in mind that personality plays a larger role in the SB of young patients. Compared with older patients, Axis II comorbidity has been repeatedly associated with completed suicides among the young (Turecki 2005). In other words, the treatment of personality disorders should be particularly intensive for young people at risk.

5 Conclusion

PDs and personality traits have a well-documented effect on suicide risk. Cluster B disorders, such as BPD, are among the mental disorders more intensely associated with suicidal outcomes, especially when comorbid with major depression. There is increasing evidence supporting an endophenotype of impulsive aggression that would mediate the relationship between cluster B disorders and SB (Turecki 2005). This knowledge is progressively being translated into effective interventions (DBT, MBT, ACT), some of them being personality specific. Among the needs, further studies should investigate the specific effect of less common PDs (in clusters A and C) while considering the extensive comorbidity of these entities and their dimensionality (Ansell et al. 2015). However, any intervention with “risky” personalities, very often coming to the emergency room only after a suicide attempt, should cultivate their observance and commitment with potential treatments.

Notes

- 1.

The DSM-5 does not use anymore clusters of PD, but most clinicians continue using DSM-IV PD clustering system.

References

Anestis MD, Gratz KL, Bagge CL, Tull MT (2012) The interactive role of distress tolerance and borderline personality disorder in suicide attempts among substance users in residential treatment. Compr Psychiatry 53:1208–1216. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.04.004

Anestis MD, Soberay KA, Gutierrez PM et al (2014) Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 18:366–386. doi:10.1177/1088868314535988

Ansell EB, Wright AGC, Markowitz JC et al (2015) Personality disorder risk factors for suicide attempts over 10 years of follow-up. Personal Disord: Theory Res Treat 6:161–167. doi:10.1037/per0000089

Apter A, Bleich A, King RA et al (1993) Death without warning? A clinical postmortem study of suicide in 43 Israeli adolescent males. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:138–142

Black DW (2015) The natural history of antisocial personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry 60:309–314

Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-García E, Saiz-Ruiz J (2007) Personality disorders and suicide. Nova Science Publishers, New York

Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-García E, Dervic K et al (2009a) Severity of personality disorders and suicide attempt. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119:149–155. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01284.x

Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-García E, Dervic K et al (2009b) Specific features of suicidal behavior in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 70:1583–1587. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04899

Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-García E, Duberstein P et al (2010) An exploratory study of the relationship between diverse life events and specific personality disorders in a sample of suicide attempters. J Pers Disord 24:773–784. doi:10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.773

Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B et al (2003) Peripubertal suicide attempts in offspring of suicide attempters with siblings concordant for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatr 160:1486–1493

Brodsky BS, Groves SA, Oquendo MA et al (2006) Interpersonal precipitants and suicide attempts in borderline personality disorder. Suicide Life Threat Behav 36:313–322. doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.313

Bronisch T (2007) The relationship between suicidality and depression. Arch Suicide Res 2:235–254. doi:10.1080/13811119608259005

Checknita D, Maussion G, Labonte B et al (2015) Monoamine oxidase A gene promoter methylation and transcriptional downregulation in an offender population with antisocial personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry 206:216–222. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144964

Cheng AT (1995) Mental illness and suicide. A case-control study in east Taiwan. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:594–603

Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA (1997) Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 170:441–446

Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF (2007) Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatr 164:922–928. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.922

Courtet P, Gottesman II, Jollant F, Gould TD (2011) The neuroscience of suicidal behaviors: what can we expect from endophenotype strategies? Transl Psychiatry 1:e7. doi:10.1038/tp.2011.6

Dalca IM, McGirr A, Renaud J, Turecki G (2013) Gender-specific suicide risk factors: a case-control study of individuals with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 74:1209–1216. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08180

Davidson KM, Tran CF (2014) Impact of treatment intensity on suicidal behavior and depression in borderline personality disorder: a critical review. J Pers Disord 28:181–197. doi:10.1521/pedi_2013_27_113

Ducasse D, René E, Béziat S et al (2014) Acceptance and commitment therapy for management of suicidal patients: a pilot study. Psychother Psychosom 83:374–376. doi:10.1159/000365974

Dumais A, Lesage AD, Alda M et al (2005) Risk factors for suicide completion in major depression: a case-control study of impulsive and aggressive behaviors in men. Am J Psychiatr 162:2116–2124. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2116

Forman EM (2004) History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. Am J Psychiatr 161:437–443. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437

Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, Patterson C (1999) Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry 175:175–179

Frances A, Fyer M, Clarkin J (1986) Personality and suicide. Ann N Y Acad Sci 487:281–295. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb27907.x

García-Nieto R, Blasco-Fontecilla H, de Leon-Martinez V, Baca-García E (2014) Clinical features associated with suicide attempts versus suicide gestures in an inpatient sample. Arch Suicide Res 18:419–431. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.845122

Garvey MJ, Spoden F (1980) Suicide attempts in antisocial personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 21:146–149

Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS et al (2004) Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 65:948–958

Gvion Y, Apter A (2011) Aggression, impulsivity, and suicide behavior: a review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res 15:93–112. doi:10.1080/13811118.2011.565265

Hawton K, Houston K, Haw C et al (2003) Comorbidity of axis I and axis II disorders in patients who attempted suicide. Am J Psychiatr 160:1494–1500

Hayashi N, Igarashi M, Imai A et al (2015) Pathways from life-historical events and borderline personality disorder to symptomatic disorders among suicidal psychiatric patients: a study of structural equation modeling. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 69:563–571. doi:10.1111/pcn.12280, n/a–n/a

Heisel MJ, Links PS, Conn D et al (2007) Narcissistic personality and vulnerability to late-life suicidality. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 15:734–741. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180487caa

Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Oquendo MA et al (2006) Aggressiveness, not impulsiveness or hostility, distinguishes suicide attempters with major depression. Psychol Med 36:1779–1788. doi:10.1017/S0033291706008725

Kendell RE (1983) DSM-III: a major advance in psychiatric nosology. International perspectives on DSM-III. American Psychiatric Press, Arlington

Kernberg OF (1993) Severe personality disorders. Yale University Press, New Haven

Kolla NJ, Eisenberg H, Links PS (2008) Epidemiology, risk factors, and psychopharmacological management of suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Arch Suicide Res 12:1–19. doi:10.1080/13811110701542010

Konrath S, Meier BP, Bushman BJ (2014) Development and validation of the Single Item Narcissism Scale (SINS). PLoS One 9:e103469. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103469

Kröger C, Roepke S, Kliem S (2014) Reasons for premature termination of dialectical behavior therapy for inpatients with borderline personality disorder. Behav Res Ther 60:46–52. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.001

Lambert MT (2003) Suicide risk assessment and management: focus on personality disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 16:71

Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC (2007) DSM-IV personality disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. BPS 62:553–564. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019

Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Ward-Ciesielski EF (2012) Assessing and managing risk with suicidal individuals. Cogn Behav Pract 19:218–232. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.11.008

Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS et al (2015) Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 72:1–8. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039

Links PS, Gould B, Ratnayake R (2003) Assessing suicidal youth with antisocial, borderline, or narcissistic personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry 48:301–310

López-Castromán J, Galfalvy H, Currier D et al (2012) Personality disorder assessments in acute depressive episodes. J Nerv Ment Dis 200:526–530. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318257c6ab

Lopez-Castroman J, Jaussent I, Beziat S et al (2014) Increased severity of suicidal behavior in impulsive aggressive patients exposed to familial adversities. Psychol Med 1–10. doi:10.1017/S0033291714000646

Lopez-Castroman J, Nogue E, Guillaume S et al (2015) Clustering suicide attempters: impulsive-ambivalent, well-planned or frequent (in press)

Marttunen MJ, Aro HM, Henriksson MM, Lönnqvist JK (1994) Antisocial behaviour in adolescent suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 89:167–173

McGirr A, Paris J, Lesage A et al (2007) Risk factors for suicide completion in borderline personality disorder: a case-control study of cluster B comorbidity and impulsive aggression. J Clin Psychiatry 68:721–729

Mendez-Bustos P, de Leon-Martinez V, Miret M et al (2013) Suicide reattempters. Harv Rev Psychiatry 21:281–295. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000001

Miles CP (1977) Conditions predisposing to suicide: a review. J Nerv Ment Dis 164:231–246

Neacsiu AD, Rizvi SL, Linehan MM (2010) Dialectical behavior therapy skills use as a mediator and outcome of treatment for borderline personality disorder. Behav Res Ther 48:832–839. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.017

Oldham JM (2006) Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatr 163:20–26. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.20

Ortigo KM, Westen D, Bradley B (2009) Personality subtypes of suicidal adults. J Nerv Ment Dis 197:687–694. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b3b13f

Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D et al (2015) Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54:97–107. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009, e2

Pallaskorpi SK, Isometsä ET, Henriksson MM et al (2005) Completed suicide among subjects receiving psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom 74:388–391. doi:10.1159/000087789

Paris J (2004) Half in love with easeful death: the meaning of chronic suicidality in borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 12:42–48

Perry JC (1989) Personality disorders, suicide and self-destructive behavior. In: Jacobs D, Brown H (eds) Suicide understanding and responding. International Universities Press, Madison, pp 157–169

Pompili M, Ruberto A, Girardi P, Tatarelli R (2004) Suicidality in DSM IV cluster B personality disorders. An overview. Ann Ist Super Sanita 40:475–483

Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Tatarelli R (2005) Suicide in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatry 59:319–324. doi:10.1080/08039480500320025

Pretorius HW, Bodemer W, Roos JL, Grimbeek J (1994) Personality traits, brief recurrent depression and attempted suicide. S Afr Med J 84:690–694

Rajalin M, Wickholm-Pethrus L, Hursti T, Jokinen J (2009) Dialectical behavior therapy-based skills training for family members of suicide attempters. Arch Suicide Res 13:257–263. doi:10.1080/13811110903044401

Ronningstam EF, Maltsberger JT (1998) Pathological narcissism and sudden suicide‐related collapse. Suicide Life Threat Behav 28:261–271. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1998.tb00856.x

Roth KB, Borges G, Medina Mora ME et al (2011) Depressed mood and antisocial behavior problems as correlates for suicide-related behaviors in Mexico. J Psychiatr Res 45:596–602. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.009

Roy A, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Branchey M (2014) Comparisons of prisoners who make or do not make suicide attempts and further who make one or multiple attempts. Arch Suicide Res 18:28–38. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.801816

Rubio Larrosa V (2004) Comportamientos suicidas y trastorno de la personalidad. In: Bobes J, Saiz P (eds) Comportamientos suicidas. Prevención y tratamiento. Ars Medica, Barcelona. pp 222–231

Rujescu D, Giegling I (2012) Intermediate phenotypes in suicidal behavior focus on personality. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Santana GL, Coelho BM, Borges G et al (2015) The influence of parental psychopathology on offspring suicidal behavior across the lifespan. PLoS One 10:e0134970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134970

Saunders KEA, Hawton K (2009) The role of psychopharmacology in suicide prevention. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 18:172–178

Sayar K, Ebrinc S, Ak I (2001) Alexithymia in patients with antisocial personality disorder in a military hospital setting. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 38:81–87

Schneider B, Schnabel A, Wetterling T et al (2008) How do personality disorders modify suicide risk? J Pers Disord 22:233–245. doi:10.1521/pedi.2008.22.3.233

Segal DL, Marty MA, Meyer WJ, Coolidge FL (2012) Personality, suicidal ideation, and reasons for living among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 67:159–166. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr080

Shea MT, Stout R, Gunderson J et al (2002) Short-term diagnostic stability of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Am J Psychiatr 159:2036–2041

Soloff PH, Chiappetta L (2012a) Subtyping borderline personality disorder by suicidal behavior. J Pers Disord 26:468–480. doi:10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.468

Soloff PH, Chiappetta L (2012b) Prospective predictors of suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder at 6-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 169:484–490. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11091378

Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM et al (2000) Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: a comparative study. Am J Psychiatr 157:601–608

Soloff PH, Fabio A, Kelly TM et al (2005) High-lethality status in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 19:386–399. doi:10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.386

Stone MH (1989) Long-term follow-up of narcissistic/borderline patients. Psychiatr Clin N Am 12:621–641

Teraishi T, Hori H, Sasayama D et al (2014) Relationship between lifetime suicide attempts and schizotypal traits in patients with schizophrenia. PLoS One 9:e107739. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107739

Tracie Shea M, Edelen MO, Pinto A et al (2009) Improvement in borderline personality disorder in relationship to age. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119:143–148. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01274.x

Turecki G (2005) Dissecting the suicide phenotype: the role of impulsive-aggressive behaviours. J Psychiatry Neurosci 30:398–408

Vijayakumar L, Rajkumar S (1999) Are risk factors for suicide universal? A case-control study in India. Acta Psychiatr Scand 99:407–411

While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A et al (2012) Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997–2006: a cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet 379:1005–1012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1

Yen S, Pagano ME, Shea MT et al (2005) Recent life events preceding suicide attempts in a personality disorder sample: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. J Consult Clin Psychol 73:99–105. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.99

Yen S, Weinstock LM, Andover MS et al (2012) Prospective predictors of adolescent suicidality: 6-month post-hospitalization follow-up. Psychol Med 43:983–993. doi:10.1017/S0033291712001912

Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E (2008) Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin N Am 31:527–543. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.007

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB et al (2008) The 10-year course of physically self-destructive acts reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 117:177–184. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01155.x

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G (2010) Time to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder and stability of recovery: a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 167:663–667. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081130

Zhang P, Roberts RE, Liu Z et al (2012) Hostility, physical aggression and trait anger as predictors for suicidal behavior in Chinese adolescents: a school-based study. PLoS One 7:e31044. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031044

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lopez-Castroman, J., Blasco-Fontecilla, H. (2016). How to Deal with Personality in Suicidal Behavior?. In: Courtet, P. (eds) Understanding Suicide. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26282-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26282-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-26280-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-26282-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)