Abstract

The goal of this chapter is to describe how youth leadership and coalition participation were nurtured by after-school programs and community infrastructure. Key adult allies provide insight into their role in supporting youth-led programs. They describe the changes in youth participation that they witnessed over time. Importantly, they describe changes in their own perspectives on youth leadership and participation. Moreover, they discuss youth development and the steps that they took to move into leadership positions and a more fully realized participation in coalition activities.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The youth component of the South Tucson Prevention Coalition (STPC) was the Youth-to-Youth program (Y2Y) . The Y2Y program grew out of the positive youth development strategies that Dr. Romero, Gloria Hamelitz-Lopez, Jaime Arrieta, and the STPC enacted over several years through after-school and summer research-based prevention programs and participatory action research . Y2Y has been a formal organization since 2005, after a group of 7 youth attended an international conference with STPC funds. Over the past 8 years, the youth involved with Y2Y have continually developed into robust community leaders—driven to help their peers and serve as role models for younger children to lead empowered, drug free lives.

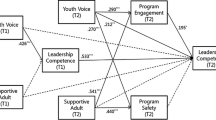

Through their own development of alcohol risk awareness and capacity to provide prevention activities, youth began to work with their peers to make smart choices, raise community awareness of the consequences of alcohol use, and community norms of availability to ultimately bring about positive youth development in the City of South Tucson. At least twice a year, Y2Y held an all-day youth retreat that they planned and led with adult guidance. Y2Y recruited new members each year, and they continued to build upon prior success in empowering youth and creating sustainable change for a healthy community. During this same time, adults were also beginning to form a coalition , South Tucson Prevention Coalition (STPC). Y2Y members regularly attended and participated in the STPC and served as key decision makers in the group through their research leadership, educational sessions, central participation in community activities, and participation in decision making (see Fig. 6.1 for an early recruitment flyer for youth).

However, it would be wrong and inappropriate to idealize or romanticize youth and their ability to create change. In fact, most individuals who work with youth on Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) would agree that there is need for adult participation , and this is usually in the form of adult allies or veteran activists (Noguera & Cannella, 2006). There, however, are few models for youth working on partnership with adults who do not already have critical consciousness about youth’s role in society and their ability to be agentic and involved in positive change. In the South Tucson Prevention Coalition , youth worked with youth and adult allies in small settings to develop critical consciousness and to engage in YPAR activities; however, one of the things that made STPC unique was that youth were then integrated into an adult coalition . This was not an easy task, and certainly the youth development programs rooted in Freirian models were fundamental to develop critical consciousness and foster leadership among youth before and during their participation with adults.At first, adults expected youth to carry out the adult decisions, or they expected that they would not participate in discussion or decision-making. Yet, it was the adults who were often surprised by the level of youth participation and by the youth’s honesty in discussions about alcohol use. In fact, some of the initial meetings were challenging for all participants, youth and adults alike. In the beginning, youth were still seen as “the problem,” due to negative stereotypes and low expectations, and adult privilege contributed to unequal relationships. However, the adults that continued to participate began to change their perspectives and their expectations of youth. They found that the youth voice added value to the conversation and to the planning of activities. They found that youth often had innovative contributions for ideas for strategies and solutions that had not been previously considered by adult leaders. Although the primary goal of the coalition was to focus on preventing underage drinking, a consequence of our YPAR approach was that adults gained critical consciousness about the humanity and equality of youth in their own community . The end result of STPC was community transformational resilience to create systemic changes to promote adolescent health in a sustainable manner. This was done in such a way to develop youth participation within the existing sociopolitical system . It was a form of disruption to the previous status quo, but executed in partnership with community leaders and adult allies.

An important element of the success of the Y2Y youth leadership program was the development of critical consciousness of the adults and their ability to facilitate and nurture youth leadership within the coalition. This chapter highlights interviews with two adult community leaders, Jaime Arrieta and Gloria Hamelitz-Lopez, who worked to provide space for youth to express their voice and to also empower youth to use their voice for good and specifically for prevention of underage drinking in their community. Gloria and Jaime both consistently framed their efforts within the larger efforts of the STPC to empower the youth of South Tucson. The sense that they were one small piece of a working organization pervaded our dialogue and is telling of one of the greatest strengths of the STPC and the larger South Tucson community. It becomes very clear in this chapter how crucial the role of continued youth leadership development was in bringing about the amazing community change that was achieved by STPC.

6.1 Gloria Hamelitz-Lopez: Youth Realities of Culture and Gender

Gloria Hamelitz-Lopez was the Executive Director of the John A. Valenzuela Youth Center (JVYC) . Her story of how she observed the youth change over the years in South Tucson involves many of the same themes that are foundational to participatory action research and serves as a parallel to what had also been seen within the partnerships that developed in the South Tucson community at large. During her interview, Gloria explained how the youth programs evolved over time at JVYC from being predominantly led by adults to being more youth-led as the coordinators re-thought the way the programs were being carried out. In particular, the participatory action research approach used as part of the Omeyocan YES and Voz programs changed their thinking:

Their main focus was the HIV prevention portion. But, what they did that was really different that I hadn’t seen in other presentations or other classes was that they had this huge focus also on Mexican American studies. And, really getting our kids empowered to make positive choices. This wasn’t a scare tactic like, “here, here’s a genital wart, look at how gross. Be scared. Don’t have sex” and, we know that those things are very short-lived, those kind of scare tactics don’t really work, you know, they may work for a little while, but, that’s about it.

And, what we saw happening was that they really talked about culture and some of our kids had never been exposed to that, we were really focused on middle school kids and beginning high school kids and they hadn’t yet been to La Raza studies classes and they just came up so empowered. They were really proud and they had seen how great all these Chicano leaders made all these differences and they stood up and they fought for all these issues in their community and they were looking around and they weren’t seeing that in their community, you know, but, what was really cool is that they kind of felt they wanted to take over and that they wanted to do something different, so, starting with that, Our kids were really, they were motivated, they were ready to go and we were kind of unsure what to do with that energy, you know, great, okay, we have standard, you know, boring stuff, “great! Let’s go clean the neighborhood”… and we wanted something different.

By making material more concretely rooted in actual lives and cultural understandings of the youth, Gloria explained that the programs became more impactful and began to spark the desire for action. It is important to note how this spark, in its small scale, was what eventually grew into the youth-led alcohol and substance use prevention program. This desire for action, as Gloria described, was the seed that eventually evolved into raising community awareness , increased youth involvement in research and action, and making presentations to the community and City Council in South Tucson in order to be civically engaged and to change city-level policy. In other words, this work created community transformational resilience by increasing positive community assets, aligning resources, and also reducing risk factors at the community level.

6.1.1 Raising the Consciousness of Adult Allies

As leaders at JVYC continued to create opportunities for youth to take on peer-to-peer leadership roles, an important moment for the youth and the adult leaders came when Gloria and others attended a Community Anti-Drug Coalition (CADCA) conference. She explained:

Part of the grant also gave our staff some money to travel and we went to a national conference…the CADCA conference…We were able to kind of go and see what other programs [were] doing nation-wide, especially programs that [were] working and one that really stuck out to us was the international youth-to-youth program…We were looking around at the conference and we had seen a lot of kids, a lot of teenagers, and I was like, how didn’t we bring teenagers to this, why didn’t that occur to us? And the more we started looking at other programs and activities, it clicked, like, this is what we need to get our kids involved in. And everything just started to snowball from there, so, that’s how the idea and premises of youth-to-youth came up.

The opportunity for national and international connections at this conference was critical and one that afforded the JVYC leaders exposure to diversity in approaches, programs, and activities which could best target the youth of South Tucson. Another important decision was for youth to attend the Y2Y international conference which was a collaborative effort among all three of the South Tucson youth centers (JVYC, HNS, and Project YES). A total of seven youth attended with the adult leaders who were excited, since they had seen how youth in other communities had been involved at the CADCA conference. The importance of seeing how other communities were working with and involving youth became clear from these experiences. These understandings were pivotal among JVYC leaders to evaluate how they were serving the youth of South Tucson and how they could do things differently and better.

6.1.2 Gaining Perspective: From Negativity to Positivity

Gloria explained what it was like the first time they attended the conference and highlighted how change did not occur “overnight” but rather was an adjustment for the youth and adult leaders alike:

We ended up becoming a group of theirs (Y2Y), which I now think we’re more successful than theirs which is really cool, but and then we were able to, with some of that extra money we had from South Tucson Prevention Collaborative : Omeyocan YES , we were able to take our kids to the youth-to-youth international conference which was in California, and that was just mind-blowing. And it was this huge week-long retreat that was focused on drugs, dating violence, on just about every issue that affects teenagers, and to see teenagers in charge of this was so surprising.

We took 3 kids from YVYS, we took 2 from HNS and 2 from Project Yes, because, you know, we still wanted to keep that whole community vibe going. And, it was almost sad, you know, this whole environment was super positive, and people were jumping and they were clapping, and our kids had never seen anything like that! You know, they were just like, they were looking around like, ‘what is this fool DOING? Why is he jumping? Why is he happy? Why is he clapping?’ And that was disturbing to me, like, what do you mean, you should be happy! Why don’t you have a happy childhood? And honestly, it actually ended up giving a couple of our kids a headache. It was just so difficult for them to process that kids were in charge, and they were happy and they were positive and they were making differences. It was just, it was too much for them, you know, and it took them a good day or two before they finally started to get into it, and they started to embrace it. And it was after that conference that they came back and they were like, ‘That was really fun! We’ve never had anything like that, EVER, not even in Tucson,’ so that kind of also started getting this whole notion started. They want to do something , they want to have healthy positive lives, and once we found out about this grant we were like, ‘Let’s do it! Let’s go, let’s see what we can accomplish with it.’ So, we were really excited, and like I said, a lot of it had to do with the prior programs that came into it. I think if we didn’t have any of that, I don’t think this would have been so successful… it was this building up of lots of different things.

The initial unfamiliarity and confusion that the South Tucson youth experienced regarding their peers at the conference is quite powerful. This experience raised the awareness and raised the expectations of both youth and adults. But this process of becoming more aware was difficult; it required some awareness of what their own community was missing and being conscious about the low expectations and negative stereotypes of youth in their own community. As Gloria explained, it was “difficult for them to process that kids were in charge” and were “happy, positive, and making differences.” The majority of youth and children (65 %) in South Tucson live in poverty, many at extreme poverty levels (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), and this is typically associated with a range of other stressors (see Chap. 1 for a more completed description of the local community). However, many of the youth were embedded in their community and may have been accustomed to this lack of resources, lack of support, and even the negative stereotypes about youth from South Tucson. Even the youth who were previously involved in community organizations and attended this conference were taken aback by the Y2Y youth leaders. This internal stress and conflict over seeing this new vision of youth action and leadership was not only negotiated by the youth. It was also present for Gloria, who explained that her understandings of the identity of the youth and where they were coming from changed. Initially, she could not make sense of the South Tucson youth’s confusion over their happy peers in leadership positions. However, she explained how rapidly South Tucson youth internalized this notion of action and leadership just over the course of the days they spent at the conference. This demonstrates how quickly critical consciousness and praxis can be stirred among adolescents when they are in the right conditions and particularly among other youth who are already engaged in action and taking on new roles that turn youth oppression upside down.

6.1.3 Shifting to Youth-Led Strategies

Putting youth in charge, and developing peer-to-peer opportunities at JVYC , was the next step to bringing youth-to-youth leadership home to their community. Thinking about the youth population in South Tucson in particular revealed an opportunity to put youth in action at JVYC:

For many years we always did leadership classes—teaching kids to be leaders and, it was basically adult-guided. Adults were up there telling you, this is how you organize, this is how you rally, and a lot of this was really just this lecture-based thing, and then there was never any action or follow-up behind it and, part of it was, kids weren’t really motivated. It was just like school: you go, you learn about something, in one ear, out the other, you took a test, and you move on. And we got tired of doing that. You know, everyone does leadership classes but we never see anything different happen.

This quote from Gloria highlights how youth leadership development may not always be nurtured in impoverished community settings, because often the infrastructure, opportunities, and expectations of leadership are missing (Rogalsky, 2009). It is exactly the missing infrastructure that Gloria and the youth became more aware of during the training and retreat sessions outside of their community. This new understanding empowered them to bring such an infrastructure to South Tucson and create structured, regular opportunities for youth to be leaders and to develop the next generation of youth leaders. Many scholars agree that didactic , lecture-based adult-led classes are not conducive to learning and certainly not conducive to internalizing leadership, civic engagement, or community change practices (Cammarota & Fine, 2008; Freire, 1968; Ginwright, Noguera, & Cammarota, 2006). Rather, engaging in participatory-based leadership was meaningful to the youth, particularly within a context in which they were supported and able to bring it back home through their activities at the JVYC (Ginwright et al., 2006).

This is another important reminder why after-school programs are often not sufficient to really create long-term change; the root of the risky behaviors is within societal infrastructure, particularly within impoverished communities, and attempts to only focus on individual responses to pervasive and constant messages and opportunities to engage in risky behavior are unsuccessful. This is exactly why community transformational resilience is necessary, particularly within low income communities with multiple layers of structural inequalities. There is a need to transform the environment in order to create more resilience promoting factors. Individual level resilience in a community with few resources and many risk factors is not likely to be enough to keep youth on a positive developmental trajectory. Furthermore, sustaining efforts to change the surrounding community is a daunting task that, for communities in poverty, has not been successful for generations—let alone something that adolescents could enact independently. They needed help from other youth and from adults who have developed a critical consciousness about the humanization and capacity of adolescent leaders.

It could have been easy for the JVYC youth to return home and perceive that the community problems were too big to change or that their own individual efforts were insufficient. And in fact, it was the critical combination of youth and adults working together that amounted to the change. With the desire to implement new techniques and to create city-level change through the support of more young people, those involved helped to grow the program into something much bigger than how it began. It was the commitment to creating change from youth and adults alike that, in the end, was transformative for the entire community’s resilience. This program was different because it prompted something to change within the youth that they could carry back to change the harsh realities that they witnessed in their own neighborhoods.

6.1.4 Relationship Approach to Prevention

Gloria went on to explain how JVYC began to pay more attention to what the youth were already doing in their existing networks and reoriented their programming to match the strengths of the youth and consider the types of interactions that were meaningful to the youth in their own community. This rethinking by the JVYC adult staff was pivotal in the way they conducted all of their programming and ultimately in the result that it had on the youth.

There were conversations, you know, we always talk to our kids, and we know everything that’s going on in their lives, and one of the things we noticed was that if one of their friends had a problem, or even one of our kids had a problem, as much as they trusted us , they wouldn’t come to us first for advice, they always went to their friends. And we started thinking about that, ‘so why aren’t we really educating the kids more’ so they can give their friends educated answers, to a problem like, ‘Hey, I think I may be pregnant,’ they were giving crazy answers like ‘Well, dude you should do jumping jacks’ or ‘drink this’ or something.

So a lot of it came from some of the one-on-one relationships we had with our kids here. We really push a relationship-based approach here. If we have a good relationship with our kids they’re so likely to, do what we ask them, like ‘Come on, join this class,’ or ‘Come on, join this, let’s do this’ so, it is a positive getting them to do really interesting things.

By contextualizing their programming in the existing social networks employed by the youth, Gloria explained that their efforts began to have more of an effective influence. In these ways, JVYC’s approach was rooted in personalismo , in other words taking a personal relationships approach to adults working with youth and youth working with their peers. Through educating youth on issues such as pregnancy, in which much misinformation and “crazy answers” are shared among youth, Gloria and JVYC tapped into the strengths and needs of the community . The peer-to-peer model was also the foundation of the Omeyocan YES program which had been successful, particularly in increasing youth knowledge and comfort in talking about substance use and risky sexual behavior prevention among teens (see Chap. 4 for details).

6.1.5 Empowering Female Youth Leadership

Two youth in particular who attended programs at JVYC stood out in Gloria’s mind when she thought about how the programs and the youth involved began to change. She explained how engaging two young women led to positive outcomes for the group. For the protection of these individuals, their names have been changed. Gloria highlighted the strengths of the youth and explained the changes that happened when they took on leadership roles:

And about that same time we had two young ladies that were here, they came to the Center. One was named ‘Yesenia’ and one was named ‘Angelina’ and… during that time I had also been the case manager here for all of the kids, and those two girls had been coming to the center since they were in Kindergarten, and, part of our measures is that okay, great, if we’ve been working with a kid since Kindergarten and now these girls are supposed to be in 11th grade, that should be kind of a mark of if we’re doing good and the problem with these girls was that they were awesome—they started off in our Girl Scouts, they were in Cross Country, they were in all these positive activities when they were in Elementary School. Middle School hit and we saw a decline. High School hit and it was a disaster. These girls had already since—for 3 years—had already been kicked out of about 12 schools, 12 different charter schools—some for drug use, some for fighting. And these girls were just, they were just, not doing well.

This anecdote is representative of national trends for Latina adolescents. For over 30 years, Latinas have had the highest rates of depressive symptoms and suicide attempts during adolescence (CDC, 2008; Eaton et al., 2008, 2011; Romero, Edwards, Bauman, & Ritter, 2013; Zayas, 2011). Depressive symptoms and suicide attempts are associated with risk factors that represent marginalization from school, peer isolation, and lack of belonging (Romero et al., 2013). While overall high school dropout rates have decreased for all groups and for Latinos specifically over the past 40 years, Latino male and female adolescents still have the highest rates of dropouts, 13.9 % and 11.3 % respectively (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Thus, Gloria’s approach to further involve the young women and link them to something important, like improving their community , and being peer role models was in so many ways a revolutionary approach to responding to young women who were clearly getting pushed out of educational systems. Additionally, Gloria’s approach demonstrated that she believed in the young women, and in fact, given her history with them, she had witnessed a positive and leadership side of the young women when they were younger. However, given the larger context of negative stereotypes of Latinas, and specifically Mexican American adolescent females from South Tucson, Gloria’s belief in something good and worthwhile in the young women was an important pushback to the messages that they were receiving from the larger society and certainly from their local school settings.

She continued:

Before I became their case worker I had worked with them on this program called, Girlz Nite, which was really a girl’s empowerment program, and these girls were bright, and they had such aspirations, and it was so sad to me to see them decline.

So, as a social worker, we really try to work at getting them back at school, kind of motivating them. We had gotten them back into Las Artes, which is a GED program here and, part of that program, as I said, we really did a lot of family involvement. It was really intensive case management. I was constantly supervising them.

And, these girls actually managed to attend their GED classes for 4 months, and not ever be late, not ever get kicked out, which was a huge feat. One of the girls, Yesenia, she got her GED, and she was really excited. But Angelina failed her GED. And I was so ready—I was like, ‘oh my god, this, she’s gonna go back, she’s gonna go back to her bad ways, I don’t know what to do ‘because she can’t do this whole program again.’ And I was just so pleasantly surprised when she said, ‘you know what? I don’t want my GED. I’m gonna go back to high school.’ And she went back to [high school], she did the accelerated program summer school and she got her high school diploma.

And that wasn’t enough… these girls wanted to go to college now.

The stark difference between the young woman who dropped out of high school and the one who was resilient even in the face of adversity lies in the investment. Gloria’s non-traditional investment in her positive development and, as a result, achievement flies in the face of all the odds that were against this young woman. Although several factors were certainly at play, the influence of youth leadership and positive programming in this young woman’s life is unambiguous. Through her involvement in the JVYC and by having a positive adult mentor such as Gloria encouraging and expecting great outcomes, Angelina began to internalize the understanding that she was able to take ownership of her aspirations and achieve them, despite whatever obstacles stood in her path. Gloria continued on and described how the two young women eventually took on roles of youth leadership with the JVYC and began to inspire within their peers the changes that they had experienced. Thus, the young women became the solution instead of the problem.

So they both decided, ‘we’re gonna go,’ it was Tucson College I think at the time, they wanted to get their medical assistant degrees, and, I was just so excited, and part of the reason that I’m selecting these two girls was because, what I started seeing was that these girls were leaders, and they kept getting all the kids riled up. They wouldn’t go and get high with themselves, they took five kids, they would come to our program, they would say ‘come on, let’s go,’ and, you know, we’re a drop-in program, we’re like, ‘Nooo! Don’t leave!’ and I started to see that but what I also started to see when they were doing good, they were telling the kids, they’d be like, ‘Hey fool, you’re not even in school, you should come to school with me,’ and they must have gotten 20 kids enrolled in Las Artes that had already been dropped out, and it was just like, ‘wow! They’re listening to these girls! That’s crazy, you know! Like, here I am, begging these kids, showing them all these things, doing a wonderful show, ‘Please come back to school, do this.’ I couldn’t get them motivated and I was just like, ‘it’s the power of teens on teens’—that peer pressure, whether it’s good or negative is so powerful!

Gloria’s description of the young women here also demonstrates how intricately linked substance use and educational outcomes are, particularly in the community of South Tucson where 42 % of the adults did not have a high school diploma (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012).

And, so, we had an idea. We’re like, you know what, we had some extra money in our budget and we needed to hire a Rec Aid and I said, ‘Why don’t we hire those two? Look at them—if they can get all these kids in high school, I bet you if we start doing this class, they’ll get all of them to join. If we start doing this… they’ll get them all to join.’ So, it really became about, let’s get them all to do positive things and it just worked out amazing.

While Gloria saw that the youth were still engaging in some risky behaviors, she also noted that they were beginning to have a positive influence on youth educational achievement. This reflection is the essence of strengths-based programs, where Gloria chose to hire the young women and to build on the strengths that they had. Her decision was also strategic because it ensured that the young women had to stay in the building—they couldn’t just “drop-in” and then leave and return again. This was much more likely to limit their opportunities to engage in substance use and thus limit the young women’s access to taking other youth with them to use substances through only “dropping-in” at JVYC . Additionally, after the Omeyocan YES program and the Y2Y program , Gloria was more aware of peer-to-peer modeling as a way to create youth change and promote adolescent health. As such, she chose to work with these young women who were peer leaders. This is a much different model than most traditional after-school models where adults teach youth in a linear manner. Moreover, her approach is significantly different from most alcohol prevention strategies that do not consider the educational context of young people. More traditional strategies also often focus on abstinence rather than accepting where youth are at and identifying present strengths in order to facilitate holistic and contextually embedded development—that is, considering their educational, peer, and after-school contexts. Lastly, Gloria’s approach demonstrated that adults would not give up on youth even if they continue to engage in risky behaviors at any level.

6.1.6 Benefits of Youth Leadership

Reflecting on how these changes were made possible, Gloria again emphasizes the role that the financial backing, that came with a new grant that grew out of relationships developed through the STPC, played in the success of their program:

I really don’t think it was until we got our Drug Free Community grant that we had some pretty big money to—we had a lot of ideas of what we wanted to do. We had projects we had seen nation-wide, and that we’ve seen in other cities that really worked, but we didn’t have the resources ourselves to do it, and we didn’t have the money. So, this grant came in to play and I think it really just gave us this awesome push that we could really do some awesome stuff with this community , and that’s really where we started to see our youth changing. It started with those two girls, it started with these classes, and it just started snowballing into something really big.

And, right now, we’re really lucky. We’ve got a great group of kids, and, you know, if we look at their successes, it’s astounding, you know, like, I feel like such a late bloomer! I mean, they have better accomplishments than I’ve ever had! And I’m jealous and proud at the same time. But, you know, we’re just really lucky. We’ve got some awesome kids and we know that it wasn’t something that happened overnight. It’s been years in the making, so, we’re really excited to be where we are now.

An important message resonates with Gloria: for as much as youth benefit from working with adults in programs such as those run through the JVYC , the adults benefit from the engagement just as much. Gloria spoke at length about giving voice and listening to youth as well as creating opportunities for youth to take on roles of leadership among their peers. The implied and overt subtext of her interview was also clear though—she and the adults at JVYC learned a tremendous amount about youth and how to help youth by engaging the very individuals they set out to assist. Once Gloria and other adults developed that critical consciousness of the youth in their own community, then there was sufficient momentum to not only keep it going but to also build more opportunities for youth. It was their consciousness about the societal context of youth behaviors, combined with a strengths-based approach, that valued, honored, and challenged the youth, inclusive of their cultural background and role as equal contributors to the community .

6.2 Jaime’s Story: Laying the Groundwork for Community Transformational Resilience

Jaime Arrieta worked as the youth outreach and prevention specialist at the Southern Arizona AIDS Foundation (SAAF) for 7 years. He played a key role in the South Tucson Prevention Coalition by linking youth with the coalition and providing continual after-school youth spaces for in-depth prevention classes and leadership training for civic engagement. In his time working at SAAF, Jaime created a prevention program called Voz (i.e., translation to the word “Voice” in Spanish) which educated youth about risky behaviors (e.g., substance use, unsafe sexual health practices, self-harm) and worked to develop life skills for community involvement and self-efficacy with youth (e.g., refusal, communication , cultural pride). This after-school program was offered at JVYC and other local areas and helped to develop a youth pipeline for the Y2Y and youth participation in the coalition. One aspect of the Voz program which differentiated it from other prevention efforts was the focus on establishing equitable dialogue among its members—valuing the voice of each individual as being of equal importance to the prevention and educational content presented. This is a fundamental approach to work relying on Freire’s (1968) model and participatory action research (McIntyre, 2008). The opportunity to learn and practice these skills in a youth-centric space was an important groundwork for the youth to be prepared to participate as equals in STPC and in future alcohol mapping PAR activities. Although Voz was created as a prevention curriculum for risky behaviors, Jaime understood that in order to truly engage the youth he would need to take a comprehensive approach to participating in youth experiences in the South Tucson community.

6.2.1 Community Level Voice and Change

Youth were encouraged to share their experiences as contextualized in their environment and cultural understandings and engaged in dialogue about the influences these contexts had on their behaviors, values, and outlook. Unsurprisingly, many graduates of Jaime’s Voz program were the youth who went on to become involved in the future activities of the STPC and Y2Y, such as the alcohol mapping project and the successful protesting of the state granting a liquor license to a local South Tucson Walgreens (see Chap. 9 for a summary). Jaime’s involvement with the youth of South Tucson was one component of the larger system of efforts working toward youth health promotion and education, but his hard work stands out as laying the groundwork for the youth-driven community changes that emerged—inspiring youth to believe in the power of their voice.

A key element of the Voz program was the active role the youth played in their learning. Rather than merely relying on presenting facts and information to the youth, the adults involved in Voz facilitated open dialogue about risky behaviors and about how risky behaviors are present in the larger community context. Jaime explained the “voice in the back of [your] head…that voice is your subconscious. It tells you what’s right and what’s wrong regardless of how you were raised. In general, you sort of know what’s right and what’s wrong.” Developmentally, adolescents can possess cognitive understandings of what is right and what is wrong. Decision-making, however, or deciding whether or not you choose the “right” or the “wrong” option is a skill that adolescents do not master until early adulthood. The Voz program encouraged the youth of South Tucson to be more conscious of their “gut” understandings and how to follow those values through openly dialoguing with informed adults about such sensitive matters. In “meeting the youth where they were,” Jaime encouraged the importance of participant voice and engagement with the curriculum. The youth were free to ask any questions they were curious about and were given the opportunity to take ownership of their voice. Thus, inspiring voice was twofold for the Voz program and STPC.

Youth participated in a photo-voice participatory action research project through Voz where they took pictures of the aspects of their community that they felt were positive influences and the aspects that they felt were negative influences. Afterward, the youth presented their findings to their youth group and engaged in critical dialogue to raise consciousness (Freire, 1968). Through this exercise, the participants of Voz developed an understanding that their perceptions and experiences mattered and that their opinions were especially important in the context of the communities in which they lived. This type of participatory action research activity laid the groundwork for later youth-led work with STPC where they took their results to the next level of sharing with the broader community of adults and civic leaders. From the Voz activities, youth learned that they could bring about community change through an internalized message that they have the right to take issue with aspects of a community that are detrimental to their health; moreover, they have the insight and ability to help their community change for the better. Some of the negative community attributes that the youth identified were trash, graffiti, alcohol consumption and signage, homelessness, gangs, and drug presence. This work was also a critical precursor for the future work on community alcohol license and signage mapping.

Jaime and Gloria took a clear stance against the faulty deficit-driven view of youth and moved toward a perspective of youth agency and capability through the programs offered and the ways in which they interacted with youth. It was these settings that were created by critically conscious adults that helped to nurture the development of youth leaders who were prepared and confident to participate in the South Tucson Prevention Coalition . Jaime explained how the Voz program challenged the youth to have an active voice in their community:

It really got the youth to be able to engage in their community and look at their community and [see] what are the problems in our community. We were able to plant some of those seeds on the educational level of like ‘Ok this is your community. What are some of the problems you see in it?’ I got to interact with these youth and help them create the need…what their need was in their community.

Through the Voz program, Jaime worked to lay the groundwork for youth to believe that they had a voice, were capable of enacting change, and had the right to better themselves and their community. These were key factors in the youth involvement in STPC. Once youth had discovered their voice it was easy to integrate them into working with the adults in the coalition . Some youth were very shy at first, and it took time before they felt comfortable to honestly share their perspectives.

6.2.2 Agency and Respect

Another key component of youth development to which Jaime frequently referred was the concept of agency or efficacy. That is, the belief that one can make decisions for him or herself and influence their self and surroundings. Inspiring the youth who were involved in Voz to believe that they could make a difference in their lives and surroundings was critical to eliciting the final outcome of true community change. It is important to note that these changes did not occur over night. As Jaime explains, “Community change is very slow. [However] when it happens it kind of has a lot of inertia.” This statement is very similar to what was noted by Gloria; once there was a breakthrough with adults and youth there are strong momentum that led to bigger changes. When asked about the youth and community reactions to the youth-initiated changes regarding the liquor signage and license denial , Jaime explained that a great deal of respect was given to the STPC and the youth involved. Jaime added that another critical thing he thought the youth took away from being involved in the community and the Voz program was respect—respect for oneself and others and the importance of being an ally. This most basic element is fundamental to working with youth of color, who often face being dehumanized, stereotyped, and disrespected on a regular basis (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). To facilitate such outcomes, Jaime made it clear that the youth were always treated with respect. He explained:

I have the grownup insight to pass along to the youth in a language they can understand without discriminating or making them feel less. It’s us talking as people not me talking to you. I’ll give you the scenario and let’s come up with the solution together.

6.2.3 The Role of Dialogue

This concept of supporting a mutual dialogue between leaders and underserved or underrepresented individuals follows a model of exploration and change as established by educational thinker, Paulo Freire (1968). Freire argued against the “banker model” of education where the student was to be “filled” with knowledge or content almost as a transaction of putting money into a vault. Instead, he passionately described a system of co-creation of knowledge between the learner and the learned with both individuals holding each role of the learner and the learned simultaneously. Parsing out the political ramifications of Freire’s work, what remains is a core value of humanizing each individual through dialogue—ensuring agency and voice for every person without hierarchy, dominance, or oppression. This is one more critical element of what allowed for such positive changes to occur in the South Tucson community. The youth were treated with respect and dignity and engaged in such a way that they became key participants in their own development.

6.2.4 Seeing Community Change as Collective

In thinking about true community change, it is critical to understand the larger community conceptions of the work being enacted. Jaime explained that outsiders wondered: “That’s really cool, how’d you do that? or How does that work?” And he would respond by saying:

Well, I didn’t do it myself. I was just a little small cog in the wheel…and it takes all of those things to make the whole thing function and you just provide whatever you can to make sure that hopefully it works.

Jaime went on to explain the importance of remaining aware of how one’s efforts fit into the larger process of change:

It’s kind of like when you’re climbing a big hill, all you really do is look down at the ground. You can’t look up because you can’t see the top of it but when you look back you look [to see] how far I’ve come. You forget to turn around and look around…and find something that is working. You gotta remember to every now and then look around and keep an eye out for the change because it might happen and you might not see it.

When asked about any advice he had for other communities to learn from STPC regarding youth-direct change, Jaime explained that communities should “learn about how to organize and get youth buy-in [with] something for the youth to focus on, giving them a project to say ‘this is what you have, this is what you get to do with it.’” In addition, he thought that organizations should “find out what are the needs of the youth, finding out the needs of the community and…how do you make it work.” Jaime stressed the importance of the adults who are leading the initiatives getting along and working together toward the larger goals of change.

Through the combined efforts of many individuals, the youth in South Tucson have the opportunity to have a voice and work toward making a change in their community, in part through their participation in STPC . By instilling a sense of agency and capability in the youth through the Voz program , Jaime has clearly worked toward laying the groundwork for youth to believe that they do have a voice and are able to bring about change and create their own realities. Encouraging this agency is no small feat and is truly a beautiful accomplishment. However, as Jaime would point it, bringing about these understandings and goals with the youth was not a one-way interaction from teacher to student. Stressing the importance of dialoguing with youth, colleagues, and the community, Jaime explained that collaboration is crucial for success at every level of the community change process. “The youth have a voice and it can be heard.”

The work that Gloria and Jaime did with youth in small groups and in providing them opportunities to understand and voice their view of their own community was critical to their ability to step up to leadership within the coalition . When his work was framed in this way and presented back, Jaime was a bit taken aback:

Robby (interviewer): Just the idea, the core idea, that what the youth have to say—[that] their voices are important—just that idea…it seems like you were really a key person in creating this concept that is so foreign—that we want to hear what you have to say…and that’s the groundwork of everything else that came. Jaime: “Thanks, wow, well you sit back and you don’t really think about it. It was just something that was fun to do and from my perspective it was empowering the youth to say ‘ok these are the problems but how do we attack them’…and coming from a community that didn’t have a lot of opportunity or their hands held by their families to do it, a lot of it came from themselves so it was really neat to watch them get inspired by it and do it.”

6.3 Conclusion

Just as Jaime made clear during his interview, the most important opportunity that an adult can give a child is a voice. And as both Gloria and Jaime explained, eliciting internalized efficacy over both oneself and context starts with that very voice. By focusing on the roles of community-based organizations (CBOs) in a student’s educational experiences, researchers can see a wider scope of ecological factors. For low-income minority families, the social and emotional adjustments of young people influence how they view their own achievements and success (Wong, 2008). The role of adults and the STPC helped to not only build community but also provide opportunities to develop the capacity of the youth by giving them room to examine the structural inequalities. The development of adult critical consciousness about youth and reframing their view of the potential of youth of color was important to the success of STPC . Additionally, the opportunities for continued youth prevention programs that were youth-space oriented were helpful to continue to feed the pipeline of youth who were ready to work with the coalition . They allowed them to examine their identities in the dominant culture and build social capital within their own neighborhood that was more meaningful to them on a cultural and economic basis (Yosso, 2005). By creating the Coalition as a site to create and maintain community norms , values, and trust , youth were given atmospheres to build social capital and examine their membership in their neighborhoods. Youth and adults worked together to create community transformational resilience .

References

Cammarota, J., & Fine, M. (2008). Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. New York: Routledge.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 57 (No. SS-4). Atlanta, GA: Author.

Eaton, D. K., Foti, K., Brener, N. D., Crosby, A. E., Flores, G., & Kann, L. (2011). Associations between risk behaviors and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: Do racial/ethnic variations in associations account for increased risk of suicidal behaviors among Hispanic/Latina 9th-to-12th grade females students? Archives of Suicide Research, 15(2), 113–126.

Eaton, D. K., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S., Ross, J., Hawkins, J., Harris, W. A., Lowry, R., McManus, T., Chyen, D., Lim, C., Brener, N. D., … Wechsler, H. (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57, No. SS-4.

Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury.

Garcia Coll, C., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Vazquez Garcia, H., et al. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914.

Ginwright, S., Noguera, P., & Cammarota, J. (Eds.). (2006). Beyond Resistance!: Youth Activism and Community Change: New democratic possibilities for practice and policy for America’s youth. New York: Routledge.

McIntyre, A. (2008). Participatory action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Noguera, P., & Cannella, C. M. (2006). Youth agency, resistance, and civic activism: The public commitment to social justice. In S. Ginwright, P. Noguera, & J. Cammarota (Eds.), Beyond resistance: Youth activism and community change (pp. 333–347). New York: Routledge.

Rogalsky J, 2009. “Mythbusters”: Dispelling the culture of poverty myth in the urban classroom. Journal of Geography 108(4), 198–209.

Romero, A. J., Edwards, L., Bauman, S., & Ritter, M. (2013). Preventing teen depression and suicide among Latinas. New York: Springer.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). South Tucson census data. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/04/0468850.html

U.S. Census Bureau, Department of Commerce. (2013). Current Population Survey (CPS), October 1967–2012. Source: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_219.70.asp

Wong, N. A. (2008). They see us as resource: The role of a community-based youth center in supporting the academic lives of low-income Chinese American Youth. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 39, 181–204

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.

Zayas, L. H. (2011). Latinas attempting suicide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Harris, R., Post, J., Arrieta, J., Hamelitz-Lopez, G. (2016). Adult Perspectives on Nurturing Youth Leadership and Coalition Participation. In: Romero, A. (eds) Youth-Community Partnerships for Adolescent Alcohol Prevention. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26030-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26030-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-26028-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-26030-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)