Abstract

Latino caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients are a fast-growing minority in San Diego County, California, as well as in the United States overall. Depression, higher levels of burden, and poorer health are common in this group. To improve quality of life for this underserved population, researchers from Stanford University partnered with the Southern Caregiver Resource Center to implement culturally tailored versions of two caregiver stress management programs derived from the original Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health and National Institute on Aging—funded projects in the southern area of San Diego County. This narrative describes how researchers and community providers collaborated to obtain funding from the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving and the San Diego County Behavioral Health Services to serve Latino caregivers in this region. The authors also highlight how two evidence-based interventions were adapted to make them feasible and culturally appropriate for Latino caregivers of low education, as well as the program’s challenges and successes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

This is the story of how academic researchers worked together with a community resource center to provide support for Latino caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients, and improve quality of life for this underserved population.

Globally, the number of older adults is increasing substantially. According to the World Health Organization [1], by the year 2050 there will be two billion people over the age of 60 around the world. In the United States, Latinos are the fastest-growing ethnic minority group. It has been estimated that older Latinos will represent 20 % of the US older population by 2050 [2]. As the average age of the population increases, the number of people developing Alzheimer’s disease also increases. In the general population of older adults, the prevalence of major neurocognitive disorder (also known as dementia) due to Alzheimer’s disease has been reported to be approximately 7 % for individuals between 65 and 74 years, 53 % for those between 75 and 84 years, and 40 % for individuals over the age of 85 years [3]. Although prevalence rates are similar, the absolute number of Latinos who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease is expected to increase 600 % by 2050 due to increasing longevity and related factors [4]. According to Clark et al. [5], Latinos start experiencing symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease approximately, on average, 7 years earlier than non-Hispanic Whites. Hinton et al. [6] describe a greater burden on Latino family caregivers due to higher prevalence of significant behavioral problems (e.g., hallucinations, aggression, wandering), suggesting that this group is in particular need of appropriate services.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association [7], there are currently approximately 15 million unpaid caregivers in the US. In the year 2012, it was estimated that these caregivers provided over 17.5 billion hours of care [7]. Family members usually become the primary caregivers of their loved ones until the illness becomes so severe that they might seek out help in long-term care facilities such as nursing homes. In many ethnically diverse communities, however, such as those of Latino and Asian origins, family members do not see nursing homes as an acceptable alternative. Generally, the oldest daughter (or son) is expected to become the primary caregiver and remain in that role for the duration of the illness [6]. In their meta-analysis, Pinquart and Sörensen [8] found that Latino and Asian American caregivers were more depressed, provided more hands-on care, had stronger filial obligation beliefs, and reported poorer physical health than non-Hispanic Whites and others with whom they were compared. It has also been reported that caregivers’ mortality rate may increase along with their stress and depression [9, 10].

Given the serious responsibilities and health risks that are associated with caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease, most caregivers would benefit from receiving information, emotional support, and skill training [11]. Many are not aware of how to obtain much needed help to decrease their levels of stress and improve their well-being, however. Latino caregivers also face other challenges, such as lack of English proficiency, financial constraints, negative stigma towards Alzheimer’s disease, and limited formal education as well as a dearth of programs developed to meet their specific needs [12, 13].

To help decrease the existing mental health services disparity among Latinos, Dr. Gallagher-Thompson and her colleagues were key participants in an influential series of studies that included a large number of Latino caregivers of elders with dementia. The first study, Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH I), was a product of collaboration among six sites in the US that recruited dementia family caregivers from Birmingham, AL; Boston, MA; Memphis, TN; Miami, FL; Palo Alto, CA; and Philadelphia, PA. The primary purpose of these projects was to tailor interventions (unique to each site) to meet the specific needs of racially and ethnically diverse clients at these locations. Latino caregivers represent a key focus at the Palo Alto and Miami sites. At Miami, 225 (114 Cuban American and 111 White American) caregivers were randomized to (1) a family-therapy-based in-home intervention, (2) a combination of that intervention and a computer telephone integration system designed to augment it, or (3) a control condition where minimal contact and support such as active listening and written information about dementia and caregiving were given to caregivers over the phone. Caregivers who received the combined intervention saw a significant reduction in depressive symptoms at 6 months. This program was particularly beneficial for Cuban American husband and daughter caregivers over time (based on follow-up at 18-months) [14].

At Palo Alto, 122 Anglo and 91 Latino caregivers of elder relatives with dementia were randomly assigned to either a cognitive behavior therapy (CBT)—based “coping skills” psychoeducational program or to a support group control condition patterned after those available in the community. Those assigned to the control condition met weekly for 12 weeks to discuss challenges and receive support from one another. In contrast, those assigned to the intervention group were given a workbook and participated in 12 small group meetings that focused on skill training. Sessions were offered in Spanish or English as appropriate. Bilingual/bicultural interventionists led the Spanish language meetings.

Each group included six to ten caregivers as a way to increase social support from nonfamily members. During these sessions caregivers learned a variety of skills for mood and behavior management (e.g., how to relax during stressful caregiving moments and how to get help and support from family members by learning to communicate effectively and express their needs). Caregivers were also encouraged to engage in pleasant activities (small and positive activities for themselves daily), with the understanding that these behaviors would help improve their mood. Since the majority reported depressive symptoms, they were also encouraged to set self-change goals and reward themselves for any accomplishments. At the end of this program, both Latino and Anglo caregivers reported fewer depressive symptoms, better coping skills, better interactions with their social networks, and more tolerance toward their care-recipient’s memory and behavioral problems than caregivers of either ethnicity in the control condition [15].

The second study, REACH II, enrolled from five of the original six sites a total of 642 dementia family caregivers: 212 were Latino, 219 were White/Caucasian, and 211 were Black/African American. Caregivers were randomly assigned, within each ethnic group, to either the control group, which consisted of minimal contact through follow-up phone calls, or the intervention group. The latter consisted of a combination of 12 behavior management-focused home visits and telephone-based support groups and discussion of the caregiver’s physical health and well-being. Caregivers in the intervention group reported greater improvement on several quality-of-life indices from pre- to post-assessment measures than those in the control condition, irrespective of race/ethnicity. One of the most significant findings of this study was that Latinos showed the greatest improvement in comparison with the other two ethnic groups [16].

The Local Community

Around the same time the researchers of the REACH I project were publishing their findings and the REACH II project was under development, California was going through some exciting changes promising to improve public mental health services. In November 2004, Proposition 63, also known as the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA), was passed, and individuals making above one million dollars started being taxed an additional 1 % on their personal income [17]. This bill provided the first opportunity in many years to expand county mental health programs for individuals throughout different age groups, including older adults and families. The primary goal of Proposition 63 was to provide prevention, early intervention, and evidence-based treatments. Each county in California was expected to come up with a plan on how to address these new demands. Roberto Velasquez was working for the Alzheimer’s Association San Diego Chapter at the time and was very aware of the high needs that Latino caregivers in that region were facing. Mr. Velasquez became part of the special community advising committee for San Diego County and realized the need for local services for Latino dementia caregivers.

To increase awareness of the need for services for dementia family caregivers among county leaders, Mr. Velasquez requested and obtained funding from the BRAVO foundation and collaborated with a team of researchers at San Diego State University (led by Drs. Ramon Valle and Mario D. Garrett) to investigate the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and associated dementias among Latinos in San Diego County. The results of their investigation suggested that the Latino population over the age of 60 is projected to grow 344 % by 2030 and 652 % by 2050. Valle et al. [18] concluded that the number of Latino family members experiencing caregiving burden and stress is expected to rapidly increase to close to 100,000 individuals by the year of 2050. Thus, creating local services to provide intervention for caregivers is imperative.

With this new information, Mr. Velasquez developed a report for San Diego County leaders explaining the demographics associated with Alzheimer’s disease and associated dementias and highlighting several other important issues. Latinos were at higher risk to develop cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, making them more vulnerable to develop Alzheimer’s disease [19]. Latinos are the fastest-growing minority in that region, and they provide care at home for their loved ones as a way to prevent institutionalization [20]. One challenge was to clarify to county leaders that the proposed services were not meant to target the medical illness of dementia but to help the caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease with their stress and depression. A second challenge was to identify evidence-based treatments for Latino caregivers, given that this population has been understudied. After a thorough literature review, Mr. Velasquez identified the REACH studies as the most reasonable choice for the proposed county program.

Academia Meets Community

The Southern Caregiver Resource Center (SCRC) is an independent nonprofit agency founded in 1987 and based in southern San Diego County. In 2009, the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving awarded the SCRC a Quality Care Connections grant of $100,000 for 2 years to implement the REACH II program with Latino caregivers. The goal of this grant was to serve 25 caregivers annually with this intensive, home-based program. Mr. Velasquez’s local advocacy efforts started to show results early in 2009, when San Diego County released a request for proposals to develop and implement services targeting Latino caregivers using one of the REACH models. Mr. Velasquez, who was by then working for the SCRC, asked Dr. Gallagher-Thompson, a principal investigator for the REACH projects, for help to write this proposal.

Dr. Gallagher-Thompson assisted Mr. Velasquez to shape the county proposal to meet the county’s goal of 200 caregivers to complete the program within a 12-month period, which could not be done if the full REACH II protocol was followed. They selected the Spanish-language version of the REACH I small group program as the most appropriate intervention for the county proposal. In late October 2009, San Diego County awarded the contract to SCRC. Thus, the SCRC would offer both programs in parallel—one to fulfill the Rosalynn Carter funding initiative and the other, the San Diego County contract.

The Partnership

To help ensure the success of these programs and overcome cultural barriers, community partnerships were established first, with organizations that already provided health-related services to the Latino community. Evidence suggests that Latinos are more likely to enroll and stay in programs when recruited through a professional referral source that is well trusted [21]. The SCRC hired four promotoras from the local San Ysidro Health Center and the La Maestra Community Health Center who were trained on topics related to dementia and caregiving stress (in addition to their role as bilingual/bicultural health educators).

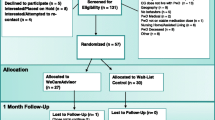

Promotoras (community peer educators/counselors or community health advocates) are essential to successful outreach in the Latino community. These trusted individuals, usually women, are friendly faces in the community that help provide information and education to families and are critical to generating referrals for the program intervention. They, an employee of the respected partner agencies, help instill confianza (trust) in the community about the program (Fig. 9.1).

“The Confianza Triangle” of successful recruitment as applied to the Southern Caregiver Resource Center (SCRC) example in this chapter. In the figure, (1) a community agency first establishes trust with Latino individuals, (2) the researcher (or SCRC) establishes trust with the community agency, and (3) the researcher (or SCRC) indirectly establishes trust with the Latino individuals

The La Maestra Community Health Center and San Ysidro Health Center were selected as partners for this program for many reasons, such as their more than 75 years of providing exemplary health and mental health services to San Diego’s Latino community, but equally important was the leadership of both these agencies. Mr. Velasquez had worked closely with the former chief executive officer of San Ysidro Health Center, Mr. Ed Martinez, for over 10 years on Latino and dementia programs, which included the Dementia Care Network project (El Portal de Esperanza, “the Portal of Hope”) developed by Mr. Velasquez in 2002 and funded by The California Endowment and a physician education project in 2003 funded by Forest Laboratories. Mr. Velasquez and Mr. Martinez engaged in collaborative programs educating families, professionals, and elected officials about the growing concern of Alzheimer’s disease and associated dementias in the Latino community.

After an introduction by Mr. Martinez, Mr. Velasquez developed a relationship with Ms. Zara Marselian, chief executive officer for La Maestra Community Health Centers, who also began collaborating on dementia-specific projects with Mr. Velasquez and Mr. Martinez. After the Dementia Care Network project ended, Mr. Martinez and Ms. Marselian jointly funded a Memory Screening Clinic in collaboration with the University of California San Diego that continues to operate to this day. When San Diego County Behavioral Health Services and Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving presented the opportunity to develop a REACH program in San Diego, Mr. Velasquez knew that both the San Ysidro Health Center and La Maestra Community Health Center would be a natural match for the program because of the commitment from their leadership.

After the partnerships were in place, a small team of external consultants was engaged to evaluate the SCRC’s readiness and cultural competence to engage the Latino community effectively and deliver the evidence-based programs with fidelity to the original REACH protocols.

Next, an advisory committee was formed, consisting of several original REACH researchers, Latino dementia caregivers, local university professors, promotoras from partnering agencies, and the SCRC’s management team. The committee met regularly to discuss ways to tailor the REACH protocols to fit the unique needs of Latino caregivers in San Diego County. The committee evaluated two proposed treatment modalities (and written materials that went with them) for their cultural relevance and sensitivity, clarity, and likely effectiveness with the target group. Special emphasis was made on certain components that these modified interventions needed to have to ensure fidelity to the original programs from which they derived. These components included keeping patients and caregivers safe; caregivers learning to manage (or respond differently) to difficult behaviors from the person with dementia; caregivers learning skills to handle negative emotions; and caregivers practicing a range of communication skills—especially how to obtain more help from other family members. Providing information on local resources was also critical. In addition, for practical reasons (e.g., staffing and overall costs), each of the original programs needed to be shortened.

Lastly, because data collection plays an important role in the evaluation of an evidence-based program, the SCRC partnered with the Health Services Research Center (HSRC) at University of California San Diego to develop a database to house the data obtained from the baseline and post-treatment assessments. The HSRC also provided technical assistance on data tracking and monitoring and prepared the empirical reports that were submitted back to funding sources.

Figure 9.2 depicts the chronology of how the partnership has formed and the actions taken to implement and evaluate the program.

Implementation: Examples of “Culturally Tailoring”

Renaming the Program

The acronym of the program, REACH, does not correspond to a word with any meaning in Spanish. Based on careful considerations from several focus groups consisting of dementia caregivers, promotoras, and care managers, we renamed REACH I (the small group program) CALMA (Cuidadores Acompañándose y Luchando para Mejorar y Seguir Adelante, which translates to “caregivers giving each other company and striving to get better and move forward”), and we renamed the REACH II program (based on in-home visits and provision of extensive information about caregiving and cognitive impairment) CUIDAR (Cuidadores Unidos Inspirados en Dar Amor y buscar Respuestas, which translates to “united caregivers to give love and seek answers”). Although the new names are not direct or literal translations, the acronyms are meaningful to the target group and conceptually appropriate.

Training the Promotoras and Care Managers

Training workshops for promotoras orient them to the SCRC services and teach them about key aspects related to dementia caregiving. The original length of the training was 10 hours (five 2-hour sessions), but we later condensed it into 5 hours due to logistical issues. Topics covered introduction to the two REACH models, eligibility criteria, and administrative protocols/procedures (e.g., referral protocols); additional services available in the San Diego area for older adults and caregivers; elder abuse and mandated reporting laws; Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related cultural beliefs (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease being equal to normal aging); skills to reduce caregiver stress; and plans for monthly promotora meetings and regular in-services. Lastly, we gave promotoras reading materials in both English and Spanish on topics related to Alzheimer’s disease and associated dementias, caregiving facts and statistics, and common signs of depression and anxiety.

The purpose of the 2-day training workshop for care managers was to train the two bilingual/bicultural master’s degree-level care managers hired by the SCRC to deliver the REACH interventions. On the first day, Dr. Gallagher-Thompson and Dr. Cardenas trained them in how to deliver the CUIDAR home-based caregiver intervention (corresponding to REACH II). They highlighted adherence to the original treatment protocol by including topics such as the following:

-

CBT (the theoretical base from which the program was developed)

-

Identifying caregivers’ risk priorities

-

Simple relaxation techniques (e.g., breathing exercises)

-

Using a “stress diary” to log stress and anxiety level daily, as well as the situations that trigger these feelings

-

Listing positive activities and tracking their completion daily

-

Developing an “action plan” for both the caregiver and care-recipient to implement skill practice

-

Using a thought record to examine and alter negative thinking patterns about caregiving

-

Completing the health passport Mi Guia de Salud (“My Health Guide”), in which caregivers record specific details related to their medical check-ups, medications taken, and medical providers’ contact information

-

Developing a “maintenance plan,” which involves asking caregivers to think about situations or events likely to occur in the next few months that will cause stress and recording skills learned in the program that can be used to help deal with the situation

On the second day, care managers, interventionists, and promotoras were brought together to learn the CALMA group program (corresponding to REACH I). They received background information and results from the original REACH I group program. During the training the interventionists participated in live demonstrations of each of the four CALMA group sessions.

Description of the Final Modified Interventions Used in San Diego County

We redesigned the CALMA small group program to include four group sessions to be offered by a trained care manager with assistance from a promotora. The care managers acted as lead group facilitators responsible for teaching the skills and exercises covered in the session. The promotoras assisted the care managers in various ways, such as walking around the classroom to assist individual caregivers with the exercises and materials (especially for caregivers with literacy issues or needing help writing their responses). We also offered three between-session telephone calls. Care managers would check in with caregivers on how things were going as they were implementing suggested changes and practicing their assigned exercises at home. The four CALMA group sessions encompass the key components from REACH I: managing stress with relaxation exercises; increasing pleasurable activities (i.e., behavioral activation); cognitive restructuring; assertiveness training to help manage anger and frustration; and getting the help one needs. We eliminated certain components from the original protocol because other SCRC services readily offered them. The format of the sessions closely followed the original REACH I procedures. For example, each session started with a review of the previous class material and home practice assignments and ended with an introduction of a new relaxation exercise. Additionally, to ensure program fidelity, we required care managers to audio-record the sessions, which a consultant later reviewed and rated, and both care managers and promotoras had opportunities to ask questions and receive feedback from weekly supervision meetings.

The CUIDAR home-based program was redesigned to include four individual home sessions offered by a care manager and three telephone calls in between home sessions (a shortened version of the original REACH II protocol). We tailored each session to the individual caregiver’s needs by determining which modules included in the Caregiver’s Guide were most relevant and important.

The decision as to which content areas would be covered was based on review of baseline assessment information and consultation with Dr. Gallagher-Thompson, who met by teleconference biweekly with the care managers for the first year of program implementation. Following the original REACH II model, each session took place with the individual caregiver in his or her home and lasted up to 2 hours. The telephone calls provided an opportunity for the care managers to check in and give feedback to the caregivers on the specific skills that were being taught.

Care managers could choose among the following modules:

-

Learning to build and maintain a strong social network (Social Support)

-

Managing caregiver stress by learning to use relaxation exercises (Managing Stress)

-

Increasing caregiver pleasurable activities (Pleasant Activities)

-

Restructuring negative or unhelpful thoughts to improve one’s mood (Understanding Your Feelings)

-

Maintaining one’s physical health by attending to the caregiver’s medical appointments and tracking personal health-related information (Healthy Life)

-

Home safety tips to reduce potential hazards or injury to dementia patient (Home Safety)

-

Tips on how to better communicate with someone diagnosed with dementia (Communicating with Your Loved One)

-

Managing difficult dementia-related behaviors, such as wandering, asking the same question repeatedly, and forgetting names and faces (My Loved One’s Behavior)

We examined the content to make it specific to the region (e.g., challenges involved in border crossing and whether comparable services would be available in Mexico to those in CA) and improve the look and feel of the materials and make them more user friendly. For example, the Caregiver Guide contained culturally appropriate photos and images throughout and had pockets to insert worksheets for each module. Every module is color-coded and includes a brief introduction to its topic to orient the caregiver to the section. Additionally, we gave special attention to the language used in each module for cultural appropriateness and ensured that the literacy level was maintained at the 6th grade level or lower to meet the average reading level of the target Latino group. Lastly, several modules included a cultural Dicho, which is a special idiom or quote known in the Latino culture that is often used to make a point or motivate a change in behavior.

We implemented several measures to maintain fidelity to the original REACH interventions. Consultants again carefully reviewed final materials, and the care managers were required to attend training sessions (described earlier) to learn the steps to deliver the interventions correctly. For both programs, care managers were required to audio-record their sessions for fidelity checks. These were done by Veronica Cardenas, who is a bilingual/bicultural Spanish speaking psychologist who worked on the original REACH projects in northern CA with Dr. Gallagher-Thompson. Feedback was provided to the care managers in a timely manner so that the interventions would be delivered as planned.

We further modified the programs following the initial launch. At first, the four sessions in both programs were to be offered every other week (per consultants’ recommendations) as a way to extend the length of contact with caregivers and allow more time for materials to be absorbed and applied to caregivers’ situations. The SCRC quickly discovered, however, that a significant number of caregivers were not returning or were missing from sessions. As a result, the four sessions were offered in consecutive weeks—a modification that significantly improved participant retention and satisfaction with the program.

Outcomes

The REACHing Out program has been successful and exceeded target expectations for enrollment. The overall program also was successful in other target outcomes related to caregiver psychological well-being, to be described below. The original target of the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving was to serve 25 Latino caregivers in one year, whereas San Diego County’s goal was to serve 200 Latino caregivers annually for the duration of the contract. Since enrollment began in June 2010 through January 2014 (the period for which data are currently available), a total of 647 caregivers enrolled in CALMA and 39 in CUIDAR. In the 2012–2013 fiscal years alone, the SCRC enrolled 231 Latino caregivers into the combined programs. Thus, these programs appear to have been well received in the Latino communities in southern San Diego County. In fact, they have now become “institutionalized” into the standard SCRC program offerings—a significant milestone that was not anticipated at the outset but is perhaps the most important outcome of this body of work.

In terms of impact of the two programs on the psychological well-being of Latino Alzheimer’s disease caregivers, we need to view results in the context of translational research—from ivory tower to community—rather than in the context of traditional academic research. This means we have to examine each program’s impact separately, keeping in mind that, contrary to traditional research methods, participants were not randomly assigned to conditions. Instead they were assigned to one program versus the other according to their levels of symptom severity at the baseline assessment, which included self-report measures of depression and perceived “burden” or stress due to caregiving. For instance, caregivers who reported high levels of depression (that is, they scored above a standardized cut-off) were generally offered the CUIDAR program so they could get more individualized help. In contrast, those whose caregiving burden was relatively high but whose depression was low were assigned to CALMA, where the small group interaction could help them learn about others in the same situation and how they were handling similar problems. In general, this system worked out well, and there were few “transfers” between programs.

Demographics

All CALMA (N = 647) and CUIDAR (N = 39) caregivers were Latinos, with a majority identifying as Mexican or Chicano (87.0 % and 89.7 %, respectively). Most in both programs were female (90.5 % and 97.4 %, respectively). CALMA caregivers tended to be older than CUIDAR caregivers; however, the majority from each program was in the age range from 40 to 59 (58.4 % and 43.6 %, respectively), which is consistent with other research with Latino Alzheimer’s disease caregivers.

Program Satisfaction

Caregivers were asked to complete several items to assess the perceived benefits of the program they had received. Most either agreed or strongly agreed that because of the program, they felt more comfortable seeking help (CALMA = 98.3 %; CUIDAR = 97.5 %). Also, virtually all reported that they were satisfied with services received (CALMA = 99.7 %; CUIDAR = 100 %).

Psychological Well-Being Outcomes

Caregivers were interviewed at baseline (upon enrollment at SCRC) and again about 6 months after participating in either CALMA or CUIDAR. A comprehensive intake assessment was done by SCRC staff that included several measures to assess psychological well-being. Of those, we will discuss three: (1) Self-rated health (the extent to which overall health was seen as interfering with caregivers’ ability to do what they wanted to do in their daily lives); (2) perceived burden or stress related to caregiving, as indexed by the Zarit Burden Interview; and (3) self-reported symptoms of depression, as indexed by the CES-D scale. The latter two are widely used in caregiver research and were used in the original REACH studies.

Perceived Health

To assess caregiver attentiveness towards his or her own health, a standalone question on the assessment tool was added: “How much does your health stand in the way of you doing the things you want to do?” There were four possible responses: “Not at All,” “A Little,” “Moderately,” and “Very Much.” This question was administered during an initial assessment prior to the REACH intervention, and again at a reassessment approximately 6 months later, after caregivers had gone through a 4-week intervention.

CALMA

During the initial assessment, 27.0 % of caregivers in this program reported that their health was either “very much” or “moderately” standing in their way of doing the things they wanted to do. At reassessment only 11.6 % reported this.

CUIDAR

At baseline, 50.0 % of caregivers in this program reported that their health was either “very much” or “moderately” standing in their way of doing the things they wanted to do. At reassessment, virtually none reported this.

Zarit Burden Interview

Caregivers were given the brief (12-item) version of the Zarit Burden Interview [22, 23], which measures perceived burden or stress related to being in the caregiving role. They rated each item on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always), with higher scores indicating greater burden, yielding a possible range of 0–44. “High Burden” is defined as greater than or equal to 8, the cut-off score typically used in research studies.

CALMA

Fewer caregivers reported high levels of burden after participating in the CALMA intervention groups. Only 15 % scored above the cut-off at the reassessment, indicating that burden was reduced for the majority of participants. A paired sample t-test was used to assess change over time and significant reduction was found: mean = 8.02 at baseline vs. 4.22 at reassessment (t (380) = 19.32, p < 0.001).

CUIDAR

Similarly, the number of caregivers reporting high levels of burden after receiving personalized intervention in the CUIDAR program drastically reduced; at reassessment, less than 10 % were still highly burdened. Note, however, the small sample size; caution should be used in interpreting these data. Again, a paired sample t-test was used to assess change over time, and significant reduction was found: mean = 10.39 at baseline vs. 2.86 at reassessment (t (27) = 11.06, p < 0.001).

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [24] is a 20-item self-report screening tool that assesses for current symptoms of depression. The CES-D has a potential range of 0–60, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms; those who score 16 or greater are considered to be experiencing a significant level of depression and likely are in need of treatment. This scale has been widely used in prior research with dementia family caregivers, including with Latino caregivers in the REACH studies.

CALMA

The number of caregivers reporting high levels of depression decreased after participating in this program. At baseline, 55.5 % were at high risk for clinical depression based on CES-D score, whereas at the reassessment only 26.6 % were at high risk. The paired sample t test showed significant reduction over time: the mean dropped from 18.18 to 11.88 (n = 452; t (451) = 13.38, p < 0.001).

CUIDAR

A similar reduction in the percentage of caregivers scoring above the clinical cut-off for depression is found here: at baseline, 76.7 % were at high risk, while at the reassessment only 10.0 % were at high risk. This finding must be evaluated in light of the fact that CUIDAR participants were selected partly on the basis of high distress in terms of initial depression level, so it is not surprising that such a high percent were clinically depressed at the outset. What is noteworthy is the highly significant drop in this percentage over time. As well, the overall mean score here dropped from 22.36 to 8.57 (n = 28; t (27) = 9.55, p < 0.001).

Lessons Learned

A key factor to the success of these projects was implementation of the “Confianza Triangle” (see Fig. 9.1) from the beginning. The promotoras’ active participation in development of materials, training sessions, and many meetings where we talked about how best to implement these programs was critical to the programs’ success. The many challenges to engaging Latino caregivers in treatment have been well documented in the literature [21, 25], and we are certain that without the promotoras’ help with outreach and engagement, the programs would not have been as successful as they turned out to be. At the same time, the use of promotoras in outreach (especially when they are not employees of the lead agency) can be a challenge. To address this challenge with the four promotoras assigned to the program (who were employed by La Maestra Community Health Center and San Ysidro Health Centers), we took multiple steps. For example, formal sub-contract agreements were created and signed by the partner agency executives along with the SCRC’s executive team. These agreements detailed the partnership and described the original REACH programs, the role of the promotoras, and the expected annual compensation to the partner agencies. We created and reviewed job descriptions and provided special trainings to teach about the original REACH models and what we wanted the new programs to achieve. Due to significant staff turnover in these jobs, this training followed a formal curriculum. Additionally, we held regular, structured meetings to review goals, referrals, outreach activities, and activity logs for reporting purposes and to answer questions and address concerns.

The annual outreach goals (N = 400 unduplicated clients) for the promotoras (described as “prevention activities”) and the intervention goals (N = 230 unduplicated clients) for the care managers up to today are very clear and restricted to the South Bay region of San Diego County. Over the program’s 5-year history, the quality of outreach contacts and referrals has improved dramatically. Roughly 9 % of all outreach contacts become referrals to the interventions. Of the referrals, approximately 47 % go through the assessment portion of the program; of those assessed, over 80 % participate and graduate from the program. Due to the restricted target region, promotoras tend to be very competitive in their outreach efforts. There is great pride in knowing that he or she made a quality referral and that the individual referred graduated from the program. In addition, the promotoras assist the care managers in the CALMA small group program, and they become a familiar face to many of the participants. To encourage healthy competition and minimize conflicts, we created a promotora coordinator position (with funding from the county) to better coordinate outreach efforts, provide mentorship and supervision, and mitigate competitive conflicts (e.g., overlapping territories, encroaching on another promotora’s community contact). This coordinator now meets weekly with the team of promotoras to review goals, referrals, outreach activities, activity logs for reporting purposes, answer questions, address concerns, and review a spreadsheet with the team that highlights referrals and graduates per promotora. This coordinator, plus SCRC’s director of education and programs, also meets with the extended group monthly—consisting of the promotoras themselves, their agency supervisors, and SCRC’s two care managers. This has really helped to improve communications among all the principal parties and helps keep the programs “on track.”

Overall, it is important to point out that through these processes and respectful listening to all stakeholders time and time again, we all learned how to work effectively together. This required flexibility and good communication to ensure that clear lines of communication were established to address problems, issues, and concerns in a timely manner. The SCRC learned that there is an ongoing need for training and supervision of all staff on the project, including management at partner agencies. The SCRC had to recognize and adjust expectations of productivity, because the turnover for promotoras was high. Meanwhile, the staff learned how to maximize their time to meet the project goals. Also, our community partners learned that in their work promoting the “new REACH,” they could also meet their own goals of obtaining referrals for their agencies.

One Partner’s Perspective: Delores Gallagher-Thompson

On a more personal level, all the researchers on the team (including me) learned that we can negotiate differences between the “ivory tower” and the “real world” in ways that respect the very different contexts we are coming from and, at the same time, develop products and services that are faithfully grounded in evidence-based principles and practices. For me, this was a remarkable, impactful learning experience—it was the first time in my professional career that I worked in such a “hands-on” way with so many different community partners who were located so far away. My previous experience focused on smaller agencies and programs in the greater San Francisco Bay area—we had our challenges and issues, of course, but because the teams were smaller and closer together geographically, resolutions were easier to come by. For REACHing Out, a number of in-person trips to the San Diego area were necessary, as well as very frequent teleconference calls and online exchanges. This experience taught me a number of skills that were rooted in its very challenges—for example, how to communicate clearly when I was not there in person and I needed to rely on electronic media to get my points across. Most importantly, it taught me how to listen well to what was being said and really pause and think before expressing opinions or recommendations. I was particularly sensitive to the fact that because I was non-Latino (in my heritage, though very Latina in my cultural preferences!), I had to listen harder and think more before speaking out. These are important lessons that I have since had the privilege to apply in other contexts—for example, training providers in Australia in the use of another derivative caregiver program (also based in the original REACH models) through use of Skype and videoconferencing. This experience would never have been one I would have done without the prior experience with REACHing Out that thoroughly prepared me for that work.

To analyze in advance the SCRC’s organization capacity was another important key to the success of these programs. It was imperative to ensure that the SCRC was ready to serve the Latino population and that it had the capacity to offer culturally appropriate services. As mentioned earlier, in order to assess for this capacity, outside experts were employed to evaluate where the organization was at the time. It was also important to keep in mind the cost to implement these programs and if this cost was manageable. In addition, it was crucial to ensure that the program being built was capable of being sustainable. A key step for sustainability was establishing collaborative partnerships with organizations in the community who were already serving the population we were looking to serve. Having discussions with these organizations early on and then creating formal partnerships with them helped tremendously during the planning and implementation phases and, later, with sustainability. Lastly, collecting impact data (using reliable measures that have been often used in caregiving research) has helped enormously to demonstrate to the funding sources, and to other interested parties, that REACHing Out is a successful model that provides tangible results and improves people’s lives.

Among the lessons learned for future projects is the need to create and implement proper documentation of the procedures and protocols at the beginning. Also, having an advisory committee that is open and flexible to change that inevitably accompanies the growth of the program proved to be an important collaboration. Maintaining open lines of communication between the researchers on the committee and the organization itself (as well as the community stakeholders) was another key factor. SCRC’s management team educated the researchers regarding the San Diego geography and SCRC’s capacity in terms of carrying out the project. Meanwhile, the researchers rolled up their sleeves on this project and adjusted their scientific expectations based on the feedback provided by SCRC and other community partners. For the academic partners, much has been learned in the process of implementing the REACH interventions in a real-world community setting. For instance, it was crucial to listen to feedback provided on the feasibility of replicating the exact same treatment models in a new environment with a different set of resources and a different target population. Additionally, academic partners balanced the need to make the programs “feasible” with the equally important need to stay true to the original model and thoughtfully consider what the key features were that had to remain. Following multiple consultations (as described above), once the best intervention models were determined, academic partners worked with SCRC to create a good “fit” between staff and caregivers. For example, staff were bilingual, bicultural, and of the same community where the caregivers resided. Academic partners also created training plans for new staff to learn how to implement the programs, and a fidelity plan to promote high quality protocol adherence.

A final lesson learned is that the burden, stress, and depression associated with dementia family caregiving can be relieved through relatively cost-effective means. Results from CALMA (the small group program) were of clinically meaningful magnitude at much less expense, compared to the home-based CUIDAR program. This underscores the importance of doing a careful caregiver assessment at the outset so that the more expensive and time-consuming services can be reserved for those who truly need them.

Future Directions

As of this writing, most of the partnerships mentioned are still active. Currently the communities being served are in close proximity to the US-Mexico border and Tijuana, Mexico. This southern part of San Diego County includes the city of San Ysidro, which is one of the busiest land border-crossings and where services are most needed. One recommendation from these findings is that funders, in collaboration with SCRC, expand this program to northern San Diego County that also has a substantial Latino population. SCRC plans to continue to lobby San Diego County for additional funding to enable this program expansion to occur. We all need to recognize that dementia is a global problem; its incidence and prevalence are rapidly rising [26]. Future partnerships with other agencies throughout the United States and even with other countries around the world would be invaluable in expanding these services to other communities that have a large Latino population with relatively low health literacy and low socio-economic status who nevertheless have significant (often unmet) service needs.

SCRC is now actively working to create a toolkit based on our new models to disseminate so that other organizations can benefit from our experience and lessons learned. The toolkit will include training materials and protocols to help build other organizations’ capacity. This should allow other community-based providers to replicate and benefit from the translational research that we have implemented, and would allow more evidence-based programs to reach populations who need them the most.

References

World Health Organization, Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia: A Public Health Priority. 2012; Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241564458_eng.pdf.

Administration on Aging. A statistical profile of Hispanic older Americans aged 65+. Department of Health & Human Services; 2010 [cited 2013 March 5]; Available from: http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/minority_aging/Facts-on-Hispanic-Elderly.aspx.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fifth edition (DSM-5). 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Alzheimer’s Association. Minorities Contract Alzheimer’s Earlier. 2011; Available from: http://www.elderauthority.com/alzheimers-association-en-espanol.

Clark CM, DeCarli C, Mungas D, Chui HI, Higdon R, Nuñez J, et al. Earlier onset of Alzheimer disease symptoms in Latino individuals compared with Anglo individuals. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(5):774–8.

Hinton L, Chambers D, Velásquez A. Making sense of behavioral disturbances in persons with dementia: Latino family caregiver attributions of neuropsychiatric inventory domains. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):401–5.

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2013 [cited 2013 september 2]; Available from: http://www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf.

Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):90–106.

Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(6):946–72.

Vitaliano PP, Young HM, Zhang J. Is caregiving a risk factor for illness? Curr Direct Psychol Sci. 2004;13(1):13–6.

Savard J, Leduc N, Lebel P, Beland F, Bergman H. Caregiver satisfaction with support services: influence of different types of services. J Aging Health. 2006;18(1):3–27.

Alvarez P, Rengifo J, Emrani T, Gallagher-Thompson D. Latino older adults and mental health: a review and commentary. Clin Gerontol. 2014;37(1):33–48.

McHenry JC, Insel KC, Einstein GO, Vidrine AN, Koerner KM, Morrow DG. Recruitment of older adults: success may be in the details. The Gerontologist. 2012 Aug 16 (Epub ahead of print).

Schulz R, Burgio L, Burns R, Eisdorfer C, Eisdorfer C, Gallagher-Thompson D, Gitlin LN, et al. Resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): overview, site-specific outcomes, and future directions. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):514–20.

Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW, Solano N, Ambler C, Rabinowitz Y, Thompson LW. Change in indices of distress among Latino and Anglo female caregivers of elderly relatives with dementia: site-specific results from the REACH national collaborative study. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):580.

Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727–38.

Mental Health Services Act. Proposition 63. [cited 2014 April 19]; Available from: http://prop63.org/about/prop-63-today/.

Valle R, Garrett Mario D, Velasquez R. Developing dementia prevalence rates among Latinos: a locally-attuned, data-based, service planning tool. J Popul Ageing. 2013;6(3):211–25.

Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, Jagust WJ. Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):169–77.

Mausbach B, Coon D, Depp C, Rabinowitz Y, Wilson-Arias E, Kraemer H, et al. Ethnicity and time to institutionalization of dementia patients: a comparison of Latina and Caucasian female family caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1077–84.

Gallagher-Thompson D, Singer LS, Depp C, Mausbach BT, Cardenas V, Coon DW. Effective recruitment strategies for Latino and Caucasian dementia family caregivers in intervention research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(5):484–90.

Zarit SH, Orr NK, Zarit JM. The hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: families under stress. New York: New York University Press; 1985.

Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–7.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Areán P. Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: issues to face, lessons to learn. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):45–51.

Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang YM, Au A, Brodaty H, Charlesworth G, Gupta R, et al. International perspectives on nonpharmacological best practices for dementia family caregivers: a review. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35(4):316–55.

Acknowledgment

This narrative is based upon work supported and funded by San Diego County Behavioral Health Services and the Rosalynn Carter Institute. The authors would like to thank Marissa Goode from the University of California San Diego for her assistance in statistical data analyses for this narrative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gallagher-Thompson, D. et al. (2015). From the Ivory Tower to the Real World: Translating an Evidence-Based Intervention for Latino Dementia Family Caregivers into a Community Setting. In: Roberts, L., Reicherter, D., Adelsheim, S., Joshi, S. (eds) Partnerships for Mental Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18884-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18884-3_9

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-18883-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-18884-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)