Abstract

The authors tell a story about the relationships built between their research team and a group of young women from low-income, underserved communities in Chicago followed for over 10 years in a seven-wave longitudinal study. The study examines two major public health concerns, sexual risk and violence exposure, in a population of young women that is overburdened with these problems yet underrepresented in most research. Longitudinal designs are invaluable in capturing change over time but entail a number of challenges, with attrition perhaps the most significant. This narrative describes how the relationships with the study participants have played an integral role in maintaining the sample and enhancing the success of the project. The authors have established meaningful relationships with participants by including community members on their recruitment and tracking team, employing an approach that blends warmth and persistence, and taking a genuine interest in participants’ lives. They have also fostered relationships with these young women by maximizing study benefits, providing support and referrals, assessing safety related to suicidal ideation and intimate partner violence, and integrating a service through testing for sexually transmitted infections. The authors hope the lessons they have learned will be helpful to other researchers who wish to conduct longitudinal studies with hard-to-reach populations.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Longitudinal study

- Community engagement

- African American

- Young women

- Adolescence

- Sexual risk

- HIV/AIDS

- Violence exposure

This is a story of a 15-year community-academic collaboration in Chicago, where work has focused on HIV risk behavior in adolescents. GIRLTALK: We Talk, the latest wave of their study, responds to the disproportionate burdens of violence and sexual health consequences faced by low-income African American girls, with an emphasis on romantic partnerships.

We recently received a call from a participant in our seven-wave longitudinal study. We had not contacted her and were not expecting follow-up at that time. She just called to say hello, to let us know that she had gotten a new job and was doing well. Like many of the young women in our study, finding work was among life’s greatest challenges. At her last research interview, this young woman had asked if we knew of any job openings. Unfortunately, this is not a service we can provide, but when she did get a job a few months later, she chose to share the good news with us. In moments like this, we realize we have built relationships that impact the lives of these young women in ways that transcend our research protocol. Our participants have come to view the study team as a source of support, and moreover, the success of our longitudinal study is based on these relationships.

This chapter tells a story of how relationships, often immeasurable and unquantifiable, can enhance science in invaluable ways. Our story is not about traditional clinical intervention or community-based participatory research in a strict sense but about how relationships are integral to carrying out successful longitudinal research with hard-to-reach populations. Relationships have allowed us to successfully retain a sample of young women from low-income, underserved communities in Chicago. These women have returned for seven waves of interviews, over more than 10 years, beginning in early adolescence and spanning into emerging adulthood. Over the years, they have been willing to share their stories, revealing sensitive and deeply personal experiences related to sexual behavior and risks, mental health, substance use, trauma, and interpersonal violence.

Introducing the Partners: The Story of Our Collaboration

We begin by describing our relationships and how our collaboration has evolved over the past 15 years (see Fig. 2.1 for a visual chronology). Dr. Wilson’s and Dr. Donenberg’s partnership began in 1998, when Dr. Wilson began her graduate research at Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine. She was among Dr. Donenberg’s first graduate students, and their collaboration has now spanned more than 15 years. Shortly after Dr. Wilson entered the graduate program in clinical psychology, Dr. Donenberg received her first grant for a project examining HIV risk behavior among adolescents in psychiatric treatment, the Chicago Adolescent Risk and Evaluation Study (CARES). Dr. Wilson completed her dissertation work with that project and continued to work with Dr. Donenberg when she moved to the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). She took on the role as project director of CARES. As a student, Dr. Wilson played a crucial role in writing a new grant to understand mother–daughter relationships and mother–daughter communication in relation to HIV-risk among low-income African American girls, a group we began to recognize as disproportionately burdened by negative health outcomes. This study, later funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, was to become GIRLTALK, the focus of this narrative.

Dr. Wilson left Chicago for fellowships on the east coast, where she completed specialized training in child and adolescent trauma and a research fellowship focused on long-term effects of child abuse and neglect. Through this work, she developed an interest in the links between trauma and risk behavior. When Dr. Wilson returned to the Chicago area for her first faculty position, she reconnected with Dr. Donenberg and the GIRLTALK study, and the two renewed their collaboration. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Wilson received her first NIH-funded grant to re-interview the young women from GIRLTALK and assess lifetime history of trauma and violence exposure, experiences that had not been adequately explored in the original study. Providers at the original recruitment sites had expressed concerns about high rates of trauma, and Dr. Wilson believed early trauma might play an important role in the development of sexual risk behavior, given that these young women were growing up in neighborhoods with high rates of violence. Over the next few years, the research with GIRLTALK shifted to the role of trauma and violence exposure in the development of sexual risk behavior. Dr. Wilson’s collaboration with Dr. Donenberg and a research team at UIC including Ms. Coleman and Dr. Floyd allowed her to take a faculty position at Stanford University School of Medicine, from where she continues to lead the GIRLTALK: We Talk study.

Ms. Coleman joined the team as the recruitment and tracking coordinator for CARES in early 2001, and she brought a wealth of research experience from working with youth and families in the surrounding Chicago areas. She originally came to UIC as a group facilitator and recruiter for a community-based intervention aimed at reducing HIV/AIDS risk in low-income, inner-city African American youth. Shortly after Dr. Donenberg moved to UIC, she met Ms. Coleman and asked her to join our team. She continued to work with us for more than 10 years. Over the course of GIRLTALK, Ms. Coleman became a legend with the families; they frequently asked about her at interview appointments and brought her baked goods for the holidays. Dr. Wilson also worked closely with Ms. Coleman on CARES, learning much about recruiting and tracking community participants and immediately thought of her as the ideal person to locate and engage the young women in her new study. Because the research team had been out of contact with many of the participants for over 3 years, Ms. Coleman’s special touch was crucial for the success of our continued follow-up. Even years after being in contact, she remembered the life stories of many participants and was able to pick up where she left off with them in the new recruitment phase.

After completing her doctoral work at the University of Kentucky, where she was involved with a mass media campaign to encourage adolescents to postpone sexual debut, Dr. Floyd entered a postdoctoral fellowship at UIC with Dr. Donenberg’s research team to continue her training with minority populations. Dr. Donenberg introduced her to Dr. Wilson, given their common interests in reducing sexual health risks among adolescent girls. They first worked together in conducting focus groups and interviews in preparation for submitting the revised GIRLTALK: We Talk grant proposal. Because of their successful collaboration on this project, Dr. Wilson asked Dr. Floyd to take the role of project director when the grant was funded, and Dr. Floyd has continued to lead data collection for this newest wave of the study.

Defining the Issues

Sexual Risk

Our research focuses on understanding and preventing sexual risk behavior in vulnerable populations. In particular, the GIRLTALK study sought to understand the role of mother–daughter relationships and communication in sexual risk taking among African American girls seeking mental health services in low-income Chicago communities. Young African American women are among demographic groups in the United States bearing the highest burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death for Black women ages 25–34 years [1], and risk for young Black women is estimated to be 20 times that for young white women [2]. Furthermore, African American women ages 15–24 are the highest risk demographic group for both chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to United States (US) public health department documentation [3]. A nationally representative study with US high school girls reported that 44 % of African American girls, as compared to 20 % of White and Mexican American girls, were infected with an STI [4]. Like other health disparities that affect minority women, disadvantages associated with living in impoverished, underserved communities likely account for disproportionate rates of STIs among young African American women [5]. Furthermore, African American adolescent girls presenting for mental health services represent a particularly vulnerable subgroup in need of effective intervention to reduce risk for STIs. Indeed, youth in psychiatric treatment tend to engage in higher rates of sexual risk behaviors than their peers [6].

Violence Exposure

Violence exposure represents another major public health problem that disproportionately impacts young women growing up in low-income urban neighborhoods [7–11]. Violence exposure is also associated with sexual risk (e.g., [7, 12–16]) and mental health problems [17]. A nationally representative US study found that 60 % of 0 to 17-year-olds experienced physical, sexual, or witnessed violence in the year preceding the study [18]. In another nationally representative study, 48 % of adolescents reported lifetime exposure to violence [19]. Research with youth in Chicago, from similar communities as the GIRLTALK women, in the 1990s reported that 26 % of youths aged 7–15 years old had witnessed a shooting, 30 % a stabbing, and 78 % a beating. Half of youth ages 10–19 years old reported physical victimization, and three fourths had witnessed a robbery, stabbing, shooting, or murder. Two thirds of high school students reported being witness to a shooting, nearly one half had witnessed a murder, and over one fourth reported being victims of physical or sexual violence [20, 21]. Given these alarming statistics and links between violence exposure and sexual risk, the newest phase of our work has focused on uncovering pathways from violence exposure to sexual risk in the GIRLTALK young women.

Minority Populations: Most Affected, Least Represented

Despite suffering disparate rates of many major health concerns, including violence and sexual risk [5], minority individuals from underserved backgrounds continue to be underrepresented in the published behavioral science literature [22]. In part, this finding relates to the fact that such populations are often hidden, difficult to reach, and distrustful of academic research, making research more costly and challenging to conduct [23]. Yet, research findings with college students or middle-class Caucasians may not generalize to all segments of the population. Moreover, designing effective interventions to reduce health risk requires inclusion of participants from the populations at highest risk. In this narrative, we describe our efforts to maintain a sample of minority women from low-income urban communities.

The Importance and Challenges of Longitudinal Research

Our research uses a longitudinal approach to understand the development of risk behavior and potential risk and protective factors. Most existing research on sexual risk is cross-sectional, correlating reported behavior with reported risk factors, such as early violence exposure. Although cross-sectional studies are cost-effective and play a critical role in the initial stage of establishing a linkage, they represent only a snapshot in development and are unable to capture changes in behavior over time. Examining change over time is particularly important during the dynamic developmental stage of adolescence. Longitudinal data are also critical to understanding phenomena such as sexual behavior, which changes considerably during adolescence and young adulthood. Moreover, longitudinal research allows us to evaluate temporal order of experiences, an essential step in testing causal theories and determining ideal points and targets for intervention.

Despite the benefits of longitudinal research, it comes with a number of challenges [24]. First, this kind of research is undoubtedly an extensive undertaking that requires significant time and resources. Second, individuals who participate in longitudinal research may be unique from their peers, given the commitment required over multiple years and assessments. Third, it is possible that variables most relevant for the individuals in a longitudinal study are no longer the most significant for later generations, making results obscure by the time findings are published. Fourth, the most significant challenge of longitudinal research is perhaps attrition, which is the primary focus of this narrative.

Over the waves of a longitudinal study, participants are inevitably lost, and if attrition is high or selects for important characteristics (e.g., the highest risk or lowest risk individuals drop out at higher rates than others), findings can be biased in important ways. Thus, two of the most challenging and critical aspects of longitudinal research are reducing attrition and, when there is attrition, reducing systematic loss of participants with particular characteristics. In research with low-income, urban minority populations, these issues can be particularly challenging due to high mobility [25, 26]. The hardest-to-reach participants may be those with the most chaotic and difficult life circumstances, such as homelessness, and it is crucial that such individuals continue to be represented. This narrative describes how our relationships with the study participants have played an integral role in maintaining the sample and enhancing the success of the project.

The GIRLTALK Study

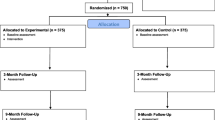

GIRLTALK is a longitudinal study that originally focused on mother–daughter relationships, mother–daughter communication, and peer and partner relationships as predictors of HIV-risk behavior among African American girls recruited from mental health agencies serving low-income communities in Chicago. The girls entered the study at ages 12–16 (average age 14). They were followed for 2 years and completed five interviews until they were ages 14–18 (average age 16). Recognizing the high rates of violence in the communities where the girls resided and the potential role of violence in risk behavior, a sixth interview at average age 17 focused on a comprehensive assessment of trauma and violence exposure, including physical, sexual, and witnessed violence. It became clear from the interviews that many girls had experienced violence in their romantic relationships, and violence involving dating partners was strongly associated with sexual risk. These findings led to the current wave of data collection addressing romantic partnerships, including partner violence, as women are entering adulthood (ages 18–25). We call this newest wave GIRLTALK: We Talk to highlight the focus on couples and dyadic relationships. Thus, relationships, first with mothers and now with partners, are central to the design of the study itself.

Embarking on this research initially involved forming relationships with community agencies and stakeholders at the mental health agencies where we identified and recruited adolescent girls and their mothers. Early in the process, we elicited input from community members to refine our questions, measures, and procedures, through focus groups, community advisory board meetings, and pilot testing. Our advisory board met annually and was integral to understanding some of the emerging trends and findings. But this story focuses primarily on the relationships we have developed with the participants themselves.

Over the first five waves of the study, we successfully retained 76–81 % of the baseline sample of 266 mother–daughter dyads. At the sixth wave, we only invited girls who participated in at least one of the five follow-up interviews. We enrolled 74 % of those who were eligible (177 out of 239), although more than a year had passed on average since the last contact, and several years had passed for many participants. Of the 177 girls who participated in Wave 6, we have so far interviewed 123 women in GIRLTALK: We Talk, and recruitment efforts are still underway with plans to enroll 130–150. We are also recruiting the young women’s romantic or sexual partners to participate. Although attrition is a risk and limitation of longitudinal research, we see our ability to remain in contact with these women as a success story. Nonetheless, we have lost a proportion of the women at each follow-up and are now facing the challenge of recruiting the most hard-to-reach participants in the sample. Predictably, over the past 10 years, the GIRLTALK women have regularly moved and changed their phone numbers, and we have had to rely on multiple contacts and chains of contact with collateral friends, family members, and community members such as pastors. In many cases, we have reached what may be dead-ends with letters returned and all available phone numbers disconnected. Next steps include going into the field and knocking on doors at the last-known residences and using online people searches. Despite these challenges, we believe our efforts to follow the women from early adolescence to emerging adulthood are worth the ability to capture developmental changes in a way that is lost in studies relying on cross-sectional designs.

The Role of Relationships in Retaining Participants

In preparing for GIRLTALK: We Talk, we mailed letters to all of the young women who participated in the sixth wave of data collection to notify them that a new study would be launching for which they may be eligible. A few months later, we received a message from a staff member in the UIC department where the original waves of the study took place (the project had moved to a new department in a new building). A woman had come to the university looking for the GIRLTALK study. It turned out that she was the mother of a participant who had received our letter, but before she could contact us or pass the information on to her daughter, the letter was lost in a house fire. And yet she recalled the letter and wanted to make sure that her daughter could participate again.

How is it that we have been able to retain this sample, with the dedication of participants exhibited by the story above? In short, trust, genuine concern, and consistent respect for each individual family’s life story. Scientifically, we have employed a number of incentives and tracking procedures found to be successful in longitudinal research [27, 28]. We provide gifts after each interview, such as T-shirts, key chains, and water bottles with the study logo. During the initial five waves, we called families monthly to update their locator information, and we began contacting families several months before the newest wave of funding came through, in anticipation of the project. We sent birthday cards with movie passes, holiday cards, and postcards with return addresses so that families could update us if they moved. We continue to send newsletters summarizing findings from GIRLTALK and related information and resources. Although these strategies undoubtedly help, we believe it is something more, something less tangible that has motivated these women to keep returning.

Relationships in the Context of Recruitment and Tracking

Including Community Members on the Recruitment Team

One critical way that we have maintained relationships with the women is in the context of recruitment and tracking. Our recruitment team includes individuals from the same or similar communities where the young women live. At times, recruiters may even encounter participants in the community. This situation can of course raise challenges. We learned that one of our recruiters, approximately the same age as the women at the current wave, went to the same high school as some of our participants. Although the situation was helpful in the recruiter being able to relate to the participants, we have had to take extra precautions regarding confidentiality. The recruiter was advised to be conscious of the similarities she has with the participants and their curiosity about her position on the research team because participants have sometimes asked her about finding similar work. We asked her to limit conversation around her personal and educational background and to redirect questions about her age, full name, or where she grew up and went to school.

Mindful of issues such as confidentially, coercion, or dual relationships, we have used community connections to build relationships. Once, at a dinner at her church, someone at the table recognized Ms. Coleman’s voice. It turned out she was a participant whom Ms. Coleman had tried to contact several times. The participant had lost our number, and we had not reached her. After this encounter, Ms. Coleman was able to schedule her assessment, and she completed the study. When recruiters go into the field to knock on doors, most people cautiously crack the door, seeming understandably wary at first. But when the recruiters mention GIRLTALK, they are usually greeted warmly invited to come inside.

An Approach that Blends Warmth and Persistence

Our recruitment approach blends warmth with persistence and recognizes that participants face numerous stressors that often take priority over participating in research. Many of the young women enrolled in our studies are in school, working, and/or raising children. Unemployment is often a serious concern that makes basic survival paramount. So when attempting to recruit these women, we are not thwarted by hang-ups, an impolite response from an individual answering the phone, or a no-show to a scheduled interview. We assume these events are not personal but, rather, that the individual is focused on other important matters that take precedence. Often, they are simply unable to think about the study at that moment. We sometimes reach a family member who does not know about the study or reacts negatively. We have found it important not to let such interactions negatively affect us. We just call back later, until we get someone else on the phone or reach the participant at a better time. While persistent, we are always friendly and, without pushing, might say something like, “I’m not trying to bug you, and if you’ve got other things to do it’s fine, just let me know a good time to call you back.” We respond to hang-ups by calling back and politely saying something like, “I believe we got disconnected” or “I’m sorry. I think I hung up on you.”

We have also learned to be flexible by calling participants at various times of day, including evenings and weekends, and asking what times are best to reach them. We make every effort to call at times convenient to the participant, which could be 10:00 at night or on a Sunday afternoon. We recognize that our participants are individuals with many other priorities, and we convey that we value their time. To enhance our recruitment efforts, we have incorporated various modes of communication, such as text messages and voice calls, and ask participants the best means to reach them. We have found that many participants avoid answering an unrecognized number and respond more quickly to a text message than a voicemail. Of course, we are respectful if a participant indicates that she no longer wants contact from us, although we have rarely had this response.

At times life will get in the way of participation, but young women who have benefited from our previous research typically find ways around life’s challenges to continue their involvement. Participants sometimes express interest in participating but ask to be contacted at a later time. For example, one young woman scheduled for a GIRLTALK: We Talk interview did not attend her scheduled appointment. After multiple attempts to contact her to reschedule, she eventually explained that she was dealing with some personal issues and asked if we would call her in a couple of months to schedule another interview. In some cases, we have scheduled recruitment calls to take place during specific times of the year due to a participant’s request. For instance, another young woman was in the process of planning her summer wedding and asked us to call her back at the beginning of the fall. She wanted to participate but could not make time for the study at the time we called due to this important life event.

A number of our participants are away at school or have relocated out of Chicago, sometimes out of the state. Some of these out-of-town participants schedule interviews when they return to Chicago, even if it means giving up time with friends and family. Others do not plan to visit Chicago, and we travel to their location to interview them. Participants who are initially hesitant to participate have brightened in tone and eagerly accepted when we offered to travel to them. One recent out-of-town participant expressed, “This study must be really important if you’re willing to come all the way to me,” and others have made similar statements.

Treating Participants as Humans, Rather Than Numbers

Our recruitment team takes genuine interest in the lives and experiences of our participants and treats them as people rather than merely research subjects we are trying to recruit. We have found that conveying interest in and showing care for what is going on in their lives goes a long way. Similarly, we find that people tend to warm up when they realize we have their interests at heart. Thus, recruiters pay attention to important events, such as birthdays, surgeries, weddings, childbirths, and family illnesses and deaths. We listen to the young women when they want to talk about their wedding plans or job searches. We are mindful of life events when we contact participants and make sure to ask about them when we do make contact. These personal touches make a difference. When participants arrive for their interviews, they usually ask to see “Miss Gloria” or other individuals who have been involved in recruitment. At the end of an interview, we often spend additional time talking with the women. Many ask about future opportunities to participate in our research studies or inquire of ways their friends or family members could get involved. We believe the young women and their mothers have learned that we genuinely care about them, and some families have said they would participate even if we offered no compensation.

Relationships Through Giving Something Back

Maximizing Benefits

Another critical aspect of our relationships with the participants involves giving back to the community, or at least to the young women participating in our study. GIRLTALK mothers often told us that they continued to participate because they felt the study benefitted their daughters, themselves, and their relationship. They particularly enjoyed a part of the study that involved mothers and daughters discussing a conflict in their relationship and trying to resolve the problem. The families appreciated the attention they received from the project staff. Although there was no active intervention, the mothers frequently shared that they felt “better” and that their daughters were “better” because they participated in GIRLTALK. This experience was shared by a participant in GIRLTALK: We Talk who expressed how much she and her mother benefited from being in the previous GIRLTALK study. She told us that before GIRLTALK she did not have a relationship with her mother, but after participating in the study, their relationship improved greatly—so much so that she relocated to be closer to her mother, and their communication remains positive today.

Similarly, the young women in GIRLTALK: We Talk tell us they have gained from thinking about their romantic relationships and participating with their partners. Many of the women have said it was helpful to participate in a videotaped interaction during which they discuss actual relationship conflicts with a romantic partner. Some participants have shared how helpful it was to talk with their partners about real relationship issues because they rarely have the opportunity to talk about these kinds of concerns. For some couples, this may be an opportunity to face topics they are avoiding. During a follow-up call, one couple told us that they decided to break up after airing conflicts during the videotaped interaction but were able to work things out and later got back together. As with the mothers and daughters, couples appear to benefit from discussing these issues in a safe, structured setting. A number of the young women and their partners have also said they enjoyed this activity as a way to help other women and couples. At the end of the partner interview, several couples have described plans to use their study compensation for a date night, and we have noticed numerous couples leave the study holding hands.

Providing Support and Referrals

Another way in which the project gives back is through careful attention to women’s safety and security. At the end of each interview, we provide referrals for mental health services and other resources if concerns such as suicidal ideation, intimate partner violence, or abuse arise, or if requested by participants. When women report relationship violence or suicidal ideation during the interview, we assess their risk of harm and help them develop safety plans. As a standard, we give everyone information about healthy relationships, recognizing when relationships are abusive, and referrals for domestic violence services including shelters, legal advocacy, and obtaining protective orders. We also offer to help link them with a service if desired. When a participant came to her GIRLTALK: We Talk appointment with a fresh black eye and limping, we were immediately concerned. During the interview, she revealed that she had been assaulted a few days earlier by members of her ex-boyfriend’s gang. We were able to provide her with a confidential hotline number through the Chicago Police Department for reporting gang-related incidents. In addition, she had not sought medical attention and accepted with appreciation our offer to walk her to the university medical center emergency department.

Although our study is not an intervention, we believe that many young women return because they feel connected to our staff, value the relationships that we continue to nurture, and have gained something meaningful from being a part of the study. This kind of relationship can also bring about challenges when participants need services we cannot provide but see our site as a safe, trusted place. When we contacted one participant to schedule her appointment with her romantic partner, she disclosed that she was experiencing abuse from her live-in boyfriend and needed help. She did not want us to call the police out of fear of negative consequences from her landlord. Instead, the young woman asked to come to our lab at UIC, over an hour away from where she lived. While respecting the participant’s wish not to involve the police, we assessed her immediate safety over the phone and kept her on the line while identifying and contacting domestic violence shelters in her community. Although we could not provide these services directly, we were able to convince her to meet with a local domestic violence advocate who would be in a better position to help her.

From a purely scientific perspective, one could argue that this kind of relationship changes the participants’ experience and access to services, and therefore threatens the validity of our findings. In clinical research, there are always important tradeoffs and balances to weigh. In this case, we strongly believe that in recruiting vulnerable, underserved populations such as these young women, the scientific costs are worth it. As they are willing to share deeply personal information, revealing experiences such as abuse and intimate partner violence, for the sake of our scientific endeavor, it is our ethical and moral obligation to provide something in return. And as this chapter emphasizes, these efforts to support and maintain positive relationships with the sample have enhanced the science in numerous ways.

Integrating a Service

In GIRLTALK: We Talk, we are able to offer an even more direct and tangible benefit to participants through tests and treatment for STIs. Scientifically, we are interested in conducting biological tests for STIs as an objective indicator of sexual risk. This choice also brings up an ethical obligation, however. Because most STIs are non-symptomatic, it is common for individuals to be unaware that they are infected. Moreover, many of the women in our study lack consistent health care. Untreated STIs can lead to negative health outcomes for individuals and have serious implications for public health. Thus, in designing this wave of the study we felt ethically obligated to provide treatment for participants who tested positive. To do this, we looked to intervention studies being conducted by Dr. Donenberg’s lab that provided testing and treatment for STIs. We decided to use the same procedures, even though our study is not intended to be an intervention.

We test each woman and her partner for three STIs—chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis—that can be tested relatively non-invasively with urine samples. We notify all participants of their results, whether positive or negative. For those who test positive, we offer no-cost treatment and counseling from a physician who is part of the study team. We coordinate these appointments and escort participants to the doctor’s office. We also offer transportation to the appointment. Thus far, 30 % of the women and 11 % of their partners have tested positive for at least one STI. Over half (54 %) have chosen to see our doctor, and an additional 33 % told us they received appropriate treatment from their personal doctor. A particularly meaningful experience occurred when both members of a couple tested positive and chose to schedule their treatment and counseling together. We were able to transport the couple to an appointment with the study doctor. While biological tests for STIs meet a scientific aim of the study in providing objective data demonstrating risk, these procedures also allow us to offer participants a valuable intervention and service.

As well as enhancing relationships with the participants and fulfilling what we believe is our ethical obligation, this kind of intervention offers a different approach than much traditional research. Over the history of clinical research, underserved populations have often been exploited—horrific examples such as the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment come to mind. We tend to think of these kinds of transgressions as artifacts of the past, but HIV/AIDS research as recently as the 2000s has been plagued with controversies around withholding of treatment [29]. Although we are not engaged in community participatory research to develop an intervention per se, we provide support and assistance in getting treatment for those who reveal clinical concerns. Thus, in addition to benefitting individual participants, these actions may help to foster greater trust in research institutions [30]. Our work is associated with the Community Outreach Intervention Projects (COIP), a public health program within the UIC School of Public Health that has been involved with the community for over 25 years, providing much needed medical care and other services to individuals from low-income communities of Chicago and integrating research and interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS.

What Have We Learned?

The ultimate goal of our research is to inform the design of intervention and prevention efforts to reduce risk for problems such as STIs and intimate partner violence among women who are disproportionately affected by these problems. With longitudinal data, we are able to identify risk markers, protective factors, and health outcomes across different stages of development. For example, we have found that in early adolescence, girls’ sexual experience was associated with externalizing problems (e.g., aggression, delinquency), more permissive parenting, less open mother–daughter sexual communication, and more frequent mother–daughter communication [31]. Among sexually active girls, mother–daughter attachment was associated with more consistent condom use [31]. Other findings suggest that family and peer relationships work together to influence sexual risk. Stronger mother–daughter attachment was associated with having less risky peers, which was in turn linked to less sexual risk behavior self-reported by the girls [32]. Results from the original GIRLTALK waves formed the basis for a mother–daughter intervention to reduce HIV risk, which is currently being evaluated in a randomized clinical trial with girls from the same low-income communities in Chicago.

Incorporating Wave 6 data, we are now examining the role of violence exposure in the development of sexual risk behavior. So far, we have found that violence exposure during childhood was associated with increased likelihood of sexual activity in early adolescence, but only risk behaviors (e.g., inconsistent condom use and multiple partners) during late adolescence when sexual activity is normative [33]. We have also found that violence in the context of romantic relationships, as compared to relationships with family members, peers, or other community members, is most strongly associated with sexual risk in our sample [7]. These findings led to the development of the GIRLTALK: We Talk study focused on romantic relationships. Dr. Wilson is now designing an intervention that combines elements of empirically supported interventions for trauma, HIV risk, and dating violence to promote healthy romantic relationships in girls with histories of violence exposure.

Recommendations for Building Relationships in Longitudinal Research

Our experience with this longitudinal study with young women in Chicago has provided us with a unique perspective, which we hope will be helpful for other researchers. We have learned a number of lessons that may be useful for research teams who wish to conduct similar research that involves following hard-to-reach populations over time. First, it is essential to develop strong relationships with community stakeholders and representatives during the initial stages of the research design and plans. Second, we have found it to be extremely beneficial to select recruiters and assemble recruitment teams who have backgrounds and experiences that reflect those of the participant population. Third, a recruitment approach blending warmth and persistence is most effective. It is helpful for recruiters to maintain a “thick skin” so that they remain positive, friendly, and persistent despite inevitable rejection and difficulty finding participants. It is equally important that the recruiter treats each participant as a unique individual and takes interest in participants’ lives, noting the best times to reach them and remembering important life events. Fourth, we suggest that finding ways to directly benefit participants in longitudinal research is not only an ethical obligation but also enhances relationships and retention. Beyond enhancing science and fulfilling our ethical obligations, we have found that this approach and the relationships built make the work particularly meaningful for our research team.

Adequate representation of ethnic and racial minorities in research is essential for reducing health disparities in the USA, and effective recruitment and retention is necessary for adequate representation. Other researchers have found that strategies incorporating community involvement, in person contact, telephone follow-up, and timely incentives are likely to be most effective in recruiting and retaining minority participants [34]. Although it takes considerable effort, time, and resources, the cultivation of these approaches has proven effective in building trust and rapport with a sample of low-income African American young women, thereby allowing us to follow them from adolescence into young adulthood and now helping us to recruit their romantic partners. In order to carry out this work, we have relied on strong collaborative relationships within our research team that have evolved over more than a decade. Our partnership continues to build on past successes and the unique experiences and strengths of each team member.

Conclusion

Building relationships with our participants has been central to the success of our research following a longitudinal sample of young African American women from low-income communities in Chicago. Through their continued participation, we are gaining valuable knowledge for designing effective interventions to reduce significant public health problems, such as STIs and intimate partner violence, which disproportionately affect low-income minority women. The young women of the GIRLTALK study have gifted us with their time, dedication, and life stories. Although we have only looked into a small window of their lives, the stories they have been willing to share mean much more than a data point.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among women. CDC HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet 2008.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among African American youth. 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012.

Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1505–12.

Pearlin L, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46:205–19.

Donenberg GR, Pao M. HIV/AIDS prevention and intervention: youths and psychiatric illness. Contemp Psychiatry. 2004;2:1–8.

Wilson HW, Woods BA, Emerson E, Donenberg GR. Patterns of violence exposure and sexual risk in low-income, urban African American girls. Psychol Violence. 2012;2:194–207.

Foster H, Brooks-Gunn J, Martin A, Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Waldman ID. Poverty/socioeconomic status and exposure to violence in the lives of children and adolescents. The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 664–87.

Voisin DR. The effects of family and community violence exposure among youth: recommendations for practice and policy. J Soc Work Educ. 2007;43:51–66.

Berman SL, Silverman WK, Kurtines WM. The effects of community violence on children and adolescents: intervention and social policy. In: Bottoms BL, Kovera MB, McAuliff BD, editors. Children, social science, and the law. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. p. 301–21.

Osofsky JD. The impact of violence on children. Domest Violence Child. 1999;9(3):33–49.

Voisin DR, Neilands TB. Community violence and health risk factors among adolescents among adolescents on Chicago’s Southside: does gender matter? J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:600–2.

Brady SS, Donenberg GR. Mechanisms linking violence exposure to health risk behavior in adolescence: motivation to cope and sensation seeking. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:673–80.

Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Williams JK, Kitchen CR, Loeb T, Carmona JV, et al. Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? Implications for prevention and policy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:660–5.

Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV among victims of child abuse and neglect: a thirty-year follow-up. Health Psychol. 2008;27:49–158.

Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:711–35.

McDonald CC, Richmond TR. The relationship between community violence exposure and mental health symptoms in urban adolescents. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:833–49.

Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormrod RK, Hamby SL. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1411–23.

Hanson RF, Borntrager C, Self-Brown S, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, et al. Relations among gender, violence exposure, and mental health: The National Survey of Adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:313–21.

Jenkins EJ, Bell CC. Violence among inner city high school students and post-traumatic stress disorder. In: Friedman S, editor. Anxiety disorders in African Americans. New York: Springer; 1994. p. 76–88.

Bell CC, Jenkins EJ. Community violence and children on Chicago's Southside. Psychiatry. 1993;56(1):46–54.

Arnett JJ. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am Psychol. 2008;63(7):602–14.

Sue S. Science, ethnicity, and bias: where have we gone wrong? Am Psychol. 1999;54(12):1070–7.

Lerner RM. Methodological issues in the study of human development concepts and theories of human development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2002. p. 480–517.

Lewis DA, Sinha V. Moving up and moving out? Economic and residential mobility of low-income Chicago families. Urban Aff Rev. 2007;43.

Jelleyman T, Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:584–92.

Blachman DR, Esposito L. Getting started: answering your frequently asked questions about applied research on child and adolescent development. In: Maholmes V, Lomonaco CG, editors. Applied research in child and adolescent development: a practical guide. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2010. p. 7–37.

Kapungu CT, Nappi CM, Thakral C, Miller SA, Devlin C, McBride C, et al. Recruiting and retaining high-risk HIV adolescents into family-based HIV prevention intervention research. J Child Fam Stud. 2012;21(4):578–88.

Kazdin AE. Ethical issues and guidelines for research. Research design in clinical psychology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2003.

Smith MB. Moral foundations in research with human participants. In: Sales BD, Folkman S, editors. Ethics in research with human participants. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000.

Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Mackesy-Amiti ME. Sexual risk among African American girls: psychopathology and mother–daughter relationships. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):153–8.

Emerson E, Donenberg GR, Wilson HW. Health-protective effects of attachment among African American girls in psychiatric care. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(1):124–32.

Wilson HW, Donenberg GR, Emerson E. Childhood violence exposure and the development of sexual risk in low-income African American girls. J Behav Med. 2014;37:1091–101.

Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):1–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wilson, H.W., Coleman, G.J., Floyd, B.R., Donenberg, G.R. (2015). Building Relationships with At-Risk Populations: A Community Engagement Approach for Longitudinal Research. In: Roberts, L., Reicherter, D., Adelsheim, S., Joshi, S. (eds) Partnerships for Mental Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18884-3_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18884-3_2

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-18883-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-18884-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)