Abstract

In today’s world order, the frequency of international interactions has reached a level that was once unthinkable. As a natural consequence, international law is one of the main areas affected. Nowadays, international dispute settlement mechanisms are more vital than ever and the numbers of these mechanisms are rising sharply. However, this sudden increase has led to a phenomenon that has created concern amongst international lawyers: the so-called ‘uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals.’ This study has two complementary aims: First, using complexity theory to explain this phenomenon and arguing why it does not pose a threat to the international legal system; second, discussing why complexity theory should be referred to more to decide the future of international adjudication.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- The uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals

- International adjudication

- Complexity theory

- Complex adaptive systems

30.1 Introduction

Undeniably, the end of the Cold War radically changed the global order. As a natural consequence, international law was one of the main areas affected. The rule of law became an objective promoted in international relationships through means such as diplomacy, multinational and bilateral agreements, and international adjudication. The end of East-west hostility and the rise of globalisation lead to the creation of new international agreements and a sharp rise in the number of international courts and tribunals,Footnote 1 however, this ‘proliferation’ of international courts and tribunals brought about some concerns. For over 20 years, much has been said and written about these concerns by academics. Most strikingly, successive presidents of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) stated their concerns about the possible negative outcomes of ‘proliferation.’Footnote 2 The proliferation of international courts and tribunals has also stimulated discussion about their success and effectiveness. Studies that assess the performance of international courts and tribunals have diversified leading to different assessments.Footnote 3

‘What makes up the current structure of international adjudication?’ and ‘what this means for the future of international adjudication?’ require answering. To answer these questions, complexity theory might be a useful tool. Complexity theory examines a circumstance when many different agents are interacting with each other in several and various ways. It aims to explain the structure, behaviour and dynamics of this system of interaction. In this context, there are certain types of systems called ‘complex adaptive systems’.Footnote 4 According to the Ruhl, ‘complex adaptive systems theory studies how agents interact and the aggregate product of their interactions.’Footnote 5 Complex adaptive systems ‘combine qualities of coherent stability and disordered change to produce a sustaining, adaptive system.’Footnote 6 Therefore, complex adaptive systems stand between order and chaos, which make them significantly adaptable and resilient to external and internal changes.

As stated by Belcher, ‘Legal systems, or a subpart thereof that deals with a specific area of law, exhibit many of the characteristics of a complex adaptive system, and arguably are a complex adaptive system. Accordingly, by applying the principles of complex adaptive systems to the interdependent laws, systems, institutions and actors that interact to form a legal system, one can better break down a system’s operational format to gain a clearer insight into the how’s and why’s of the system’s functions.’Footnote 7 The authors of this article argue that the international legal system exhibits many characteristics of a complex adaptive system. These characteristics are helpful to explain the current uncoordinated proliferate structure of international adjudication. Thus, considering the international legal system and international adjudication through the lens of complex adaptive systems might provide a better understanding regarding their current structure and their future.

Therefore, Sect. 30.2 of this chapter will briefly develop the principles of a complex adaptive system and explain their relationship with the international legal system. It will argue that the international legal system demonstrates certain characteristics of a complex adaptive system, meaning that the recent uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals might be better understood and assessed from this perspective. Section 30.3 will then introduce the phenomenon called ‘the uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals’ and its related concerns. Finally, Section 30.4 will examine the current structure of international courts and tribunals and will discuss their future in the context of complex adaptive systems.

30.2 Complex Adaptive Systems Theory as a Descriptive Tool for the Recent Structure of International Adjudication

30.2.1 What Is a Complex Adaptive System?

A complex adaptive system is ‘a system in which large networks of components with no central control and simple rules of operation give rise to complex collective behaviour, sophisticated information processing, and adaptation via learning or evolution.’Footnote 8 They are a particular type of self-organizing system with emergent properties and an ability to adapt in reaction to a change of external situations.

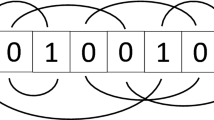

Complex adaptive systems focus on the interactions between the different agents of a particular system. These agents are interconnected and affected by each other in different ways depending on the nature of their interaction (for example, through flows of energy or information). These interactions are of a non-linear nature.Footnote 9 Therefore, rather than a specific or singular relationship or change, the aggregation of the interactions in the system determines the system’s emerging behaviours. Nevertheless, the system remains unpredictable since it is difficult to predict the outcome of the every interaction in the long term.Footnote 10

The core of complex adaptive system study is to focus on systems that have complex, macroscopic and emergent properties.Footnote 11 Accordingly, a great number of agents interact with each other in a system and they constantly adapt themselves to stay functional or to survive. All these activities create the cumulative behaviour of a ‘system,’ which is still far from being predictable in the long term due to its complex nature.Footnote 12 In the following paragraphs, the specific properties of this basic definition of complex adaptive systems will be explored, thus setting out the characteristics of a complex adaptive system.

To begin with, a fundamental distinction must be made between that the term complex and complicatedness. A complicated structure consists of various components, however if one of these components are taken out of the equation, the whole behaviour of the system does not necessarily, or fundamentally, change.Footnote 13 Conversely, complexity derives from the interdependency, non-linear interactions and attributes of the system’s components. Removing or transforming a component creates a change in the system’s overall behaviour beyond its actual value, function or embodiment.Footnote 14

This complexity helps to make a system more adaptive and resilient against changes within or to the system, since the impact of a particular change is subtilized across the system by means of feedback changes. Feedback changes simply refer to the alterations of agents’ behaviours due to feedbacks that they receive from the system.Footnote 15 When an agent changes its individual behaviour, others also react and alter theirs in respect of this change. Accordingly, while agents adapt themselves to these changes, their aggregated behaviours also make the system adaptive. The set-up of the network of agents and their casual relationships form the core of the system. Thus, their adaptive, interconnected and heterogonous structure creates a complex adaptive system.

Pauwelyn defines the certain features that complex adaptive systems share as a: ‘(i) dispersed interaction between many heterogeneous agents, (ii) leading to emergent self-organized collective behaviour, (iii) without global controller and (iv) continual adaptation with out-of-equilibrium dynamics’Footnote 16 The most common examples of complex adaptive systems are the ecosystems of biological speciesFootnote 17 and economies.Footnote 18 In this regard, Adam Smith’s invisible hand theory or ant colonies can be given as standard examples, as in both of these instances highly complex collective behaviour and physical structures emerge through various interactions, without a central control mechanism.Footnote 19

Therefore, it is evident that agents are the key elements of complex adaptive systems. Whilst the premise of complex adaptive systems study offers that the collective outcome or behaviour of a system is determined by the culmination of all agents’ individual behaviours,Footnote 20 these agents carry out their actions based on internal and external factors such as their own operational understanding, rules, interests, experiences and targets.Footnote 21 Hence, it is this heterogeneity of the agents that is significant to the outcomes and emergent behaviours of the whole system.

Nevertheless, ‘underlying all agent interactions of a complex system is often simple, deterministic rules. What makes the interactions complex is how these rules, when set in motion among the diverse components of a system, produce nonlinear relationships including reinforcing and stabilizing feedbacks.’Footnote 22 The emergence of these interactions and behaviours happen without any external and central controller, yet the system keeps its identity and functions. This is a common and defining feature of complex adaptive systems and is called ‘self-organization’.Footnote 23

In addition, change within a complex adaptive system is perpetual and strives towards a critical state of dynamic behaviour, but is not homogenous in frequency or significance. In this respect, what makes a system adaptive rather than rigid or chaotic is the critical state of ‘stable disequilibrium’.Footnote 24 This hallmark feature of complex adaptive systems indicates that a system is always dynamic and in motion but also exhibits coherence under change.Footnote 25 Therefore, a complex adaptive system operates in an area entitled the ‘edge of chaos,’ a significant mid-point between order and randomness. As Ruhl notes;

We almost invariably find change occurring in power law event distributions in which vast numbers of small changes are punctuated by infrequent large changes. Complex adaptive systems build adaptive capacity based on this kind of change regime, not based on a normal distribution. An ecosystem, for example, builds resistance capacity to withstand environmental changes such as fire regimes, and builds resilience capacity to rebound from severe incidents. (…) Notwithstanding the remarkable capacity of complex adaptive systems to maintain their properties over time, we must return to the cold, hard truth that all systems ultimately are built on deterministic rules that cannot be violated. There is a limit to the resistance and resilience of any complex adaptive system, and if pushed hard enough or persistently enough, a system might move into a phase transition through which radically new network architecture is installed.Footnote 26

Therefore, ‘complex adaptive systems theory is about building models for moderate number contexts in which agent heterogeneity can and usually does influence outcomes, and as such it is worth exploring how it might inform our understanding of the legal system’.Footnote 27 This is also helpful to better understand the uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals, since international adjudication not only derives from the complex nature of the international legal system but is also a component of it. The international legal system exhibits many characteristics of a complex adaptive system, as it is a web of treaties and institutions that self-organize and display emergent properties.Footnote 28 Thus, the complex adaptive system characteristics of the international legal system, and consequently international adjudication, should be examined in detail before the discussion of the ‘proliferation’ phenomenon.

30.2.2 International Law as a Complex Adaptive System

In any legal system, different agents interact with each other in various ways. In terms of the international legal system, the interactions are more diverse due to today’s highly interconnected world where endless factors are changing matters in an instant and extreme way. The international legal system consists of many diverse components and the evolution of international law is affected by a number of these heterogeneous components, such as: states, international organizations, international and national courts and tribunals, non-governmental organizations, individuals and so on.Footnote 29 Therefore, international law making entails a broader process than provided for in strict conventional definitions of law making because, primarily, the number of contributors or causes of law making and the processes applicable are higher than under the traditional understanding.Footnote 30

Furthermore, in the international legal system, a law or an institution always has an interrelationship with other parts of the legal system. The interactions between all these actors (agents) shape international law. The interactions not only occur in the legal sphere but also in political, cultural, scientific and military spheres because the international legal system is generally a product of international relations, the continual formal and informal relationships between the aforementioned interconnected actors. Here international relations and law go hand in hand. On the one hand, international relations can shape international law. This can be seen from events such as the Cold War and its impact on both the international legal order and interactions between states and institutions.Footnote 31 On the other hand, the emergence of international legal concepts influences actors and their relationships; an example of this is the emergence of human rights and its influence on individuals, states and European politics.Footnote 32

These bilateral and multilateral interactions, which create the international legal system, are pivotal since they prove that the creation and implementation of law is a result of multifarious interactions between different actors either in a formal or informal manner. This reveals two important complex properties of the international legal system. First, states, institutions and organizations are constantly re-defining their aims in accordance with their own dynamics as well as the ‘international set-up at that moment.’ Therefore, the rules of interaction between actors ‘do not produce behaviours that are in continuous proportionate relationships over time; sharp tipping points and discontinuities frequently occur.’Footnote 33 This indicates the non-linearity of relationships between the actors of the international legal system.

Second, the various classes of the different autonomous components of international law making indicate the heterogeneity of the international legal system’s actors. In order to achieve any significant international legal development, the support of the majority of states is needed. However, all states are legally independent and their interests and aims are varied. Moreover, with the exception of a limited number of conventions and agreements,Footnote 34 multilateral and bilateral agreements are creating independent legal islands.Footnote 35 They diverge to a significant degree in terms of their subject matters, objectives, members, regulatory mechanisms, jurisdictions, and so forth. They also frequently create their own autonomous institutional laws and give a great deal of decision-making powers, autonomous personnel and specialists to the institutions. According to complexity theory, this diversity is not random; on the contrary, it is the result of the environment of the system and the actions of the other agents.Footnote 36 This also indicates the decentralized characteristic of international law.

At the same time, the interconnection of states is getting more complex as economic, social and political dependency on each other increases as a natural consequence of globalism and technological advancement. In today’s world, an armed conflict between two states in Europe may lead to economic crisis in America; a terrorist organization based outside of Europe can attack a European State and potentially cause a political and legal crisis; or an environmental disaster in Asia may have an effect on the Artic Region. Although, in theory, all states are independent from each other, in order to cope with all these global issues that affect them collectively, they need to work together. The number of treaties, international organizations and institutions that have been established over the past few decades exemplify this rise in co-operation between the actors of the international order. This indicates the interdependence of these international actors in creating international law and in creating and running legal institutions. Accordingly, international law is a system of interdependent actors in utilitarian and component interaction, as opposed to a set of uncoordinated norms and institutions.Footnote 37

Furthermore, states and international institutions are able to learn from their past experiences and abide by lessons learnt through history as they interact. They either adapt their behaviours in accordance with past experiences or they make changes to their behaviours that were not serving their own interest. All these interactions and approaches eventually shape international law. The protection of minorities and the development of human rights are an example of this. Until the late nineteenth century, it was accepted that a state could not interfere in another state’s treatment of its own citizens due to the understanding of Westphalian sovereignty.Footnote 38 However, states re-considered this approach in the late nineteenth century in pursuit of the protections of minorities in Ottoman Empire.Footnote 39 Unfortunately, this did not help prevent the disastrous experiences of the Second World War. Following this, states began aiming to protect not only minorities in other states from abuses, but all individuals, as witnessed in the Kosovo situation in late 1990s.Footnote 40

Of course, all these experiences lead to a shift in the approaches of international actors and a consequent evolvement of international law. Our above example, has for instance, led to several different international treaties, court interpretations on law and the emergence of concepts like ‘humanitarian intervention’ or ‘responsibility to protect.’Footnote 41 This demonstrates the other complex properties of the international legal system. First of all, it illustrates how past experiences alter the approaches and actions states and institutions take in relation to the creation and implementation of international law. This indicates the feedback loops in the international legal system to which actors then make feedback changes in order to stabilize the system. Moreover, it exhibits the path dependency of the international law making and applying process; the dependency of the system’s new state on information that has flowed through the system in all its prior states.Footnote 42

More strikingly, in international relations and the international legal system, parties act according to their own interests regardless of any possible impact on the system, nevertheless, these different aims, interests and acts implicitly lead to the creation of order. This evidences another complex feature of the international legal system; its decentralized structure. As explained in Part III, international law and adjudication suffer from decentralization because there is no centralized legislature, executive or judiciary. However, states continue creating and following international rules and there is a common agreement among states to abide by the law. The international legal system consists of independent actors who look after their own interest, but need each other to maximize their interests and provide some predictability to the system. Thus, an order is created without any higher institution or power specifically designed to provide it. This leads to a complex legal structure that is self-organized. In other words, the international legal order is a ‘system [which] tends to organize around a set of deep structural rules that lend stability to system behaviour.’Footnote 43

Consequently, it is essential to not individually analyse a treaty, court, tribunal or institution, but to instead analyse the links that hold the system together in order to understand the international legal system and to reform it. As Lasin argues, ‘process that seems to be governed by chance when viewed at the level of the individual turns out to be strikingly predictable at the level of society as a whole.’Footnote 44 Thus, amplifying macroscopic patterns as a result of this non-reductionist approach rather than focusing on details is important to better understand the structure of international law and adjudication since the ‘system behaviour emerges from the aggregation of network casual chains which cannot be explained by examining any isolated part of the system.’Footnote 45 The effectiveness of international adjudication, for example, cannot be assessed by solely focussing on a limited number of components such as the judgements of certain courts, their enforcement or the number of cases that are brought before the courts and tribunals. Instead, the effectiveness should be assessed in the context of the international legal system including all its components.Footnote 46

This overlap and communality between the international legal system and the defining properties of complex adaptive systems are striking. However, as Ruhl points out, ‘showing that complex adaptive systems theory maps well onto the legal system does not (…) prove that the legal system is a complex adaptive system.’Footnote 47 Despite the remarkably similar properties, there are obvious doubts regarding applying physics and biology based theory to a social system, since people are the designers of legal systemsFootnote 48 and ultimately write the law. Furthermore, there are also some other problems with applying complex adaptive systems theory to international law that derive specifically from the nature of the international legal system. For example, it is not easy to identify the deterministic rules of the international legal system, a property that complex adaptive systems have. Ruhl provides some examples of deterministic rules applicable to law, such as court interpretations of legislation, legislature overrules, superior courts’ affirmation or reverse decisions on lower court decisions, and the implementation of statutes by agencies.Footnote 49 However, the position of courts, their decisions and the structure and powers of institutions in the international legal order differ significantly to their national counterparts. International courts’ decisions suffer from a lack of sufficient enforcement most of the time and institutions do not have the power to interfere in domestic issues unless a state permits it to do so. Nevertheless, as Ruhl explains, proving that a legal system is a complex adaptive system ‘is not the test to which the usefulness of complex adaptive systems theory should be put. Rather, it should suffice to show that the model of complex adaptive systems provides useful design lessons for the legal system.’Footnote 50

Thus, because of the many similarities pointed out between the international legal system and complex adaptive systems, the theory does appear to be a useful tool to understand, assess and reform international law (since international law is an outcome of the international legal system) and its sub-parts, including international adjudication. This approach has been followed by some scholars in relation to other sub-parts of international law such as international investment law,Footnote 51 international environmental lawFootnote 52 and international legal development.Footnote 53 As a result, some have developed criticisms and suggestions using complex adaptive system theory. One suggestion for instance, is that governance of international mechanisms and institutions should behave like a complex adaptive system in order to be efficient, arguing that adaptive or decentralised governance is more suitable then the classical hierarchical structures of the international legal order.Footnote 54

The sub-part of international law focused on in this article is international adjudication. Over the past two decades much has been said in relation to international adjudication including its significant development and, most interestingly, the uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals. Some scholars and lawyers have labelled this phenomenon a danger to the international legal order. The decentralized, fragmented, but interdependent nature of international adjudication tempts the use of the complex adaptive systems theory to explain the current situation. Thus, before the examination of the uncoordinated proliferation of international courts and tribunals in the context of complex adaptive systems theory, the phenomenon and its related discussions will be explained.

30.3 As a Phenomenon: The Uncoordinated ‘Proliferation’ of International Courts and Tribunals

The international order has changed considerably, particularly after the end of the Cold War. The amount international organizations has increased, existing organizations such as the European Union (‘EU’) have become more effective, and the rise of globalization and liberalization has created a new economic order that includes many powerful co-operational and regulative organizations and agreements such as the World Trade Organization (‘WTO’) and the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (‘NAFTA’). International courts and tribunals have also been affected. Their number has significantly increased, their subject matters have diversified, and new international courts and tribunals have started to display fundamental jurisdictional differences in comparison with their older counterparts such as the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’) or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (‘ITLOS’). Moreover, some existing courts such as the European Court of Human Rights (‘ECtHR’) and the European Court of Justice (‘ECJ’) have gained more jurisdictional powers. This recent increase in the number of international courts and tribunals has raised concerns about their ‘uncoordinated proliferation.’ The concerns include the creation of jurisdictional and normative conflicts that may pose threats to the international legal order, the fragmentation of international law which may undermine its the clarity and stability, and the resulting chaos that may potentially be caused to the international legal system.

Before further explanation in relation to the ‘uncoordinated proliferation’ phenomenon, it is necessary to define the term ‘international courts and tribunals’ for the purpose of this paper since definitions provided by different international adjudicatory bodies vary.Footnote 55 The term ‘adjudication’ usually includes both judicial bodies and arbitral methods. Both are law-based processes that can render binding decisions. However, a judicial body usually exists before a dispute arises and its adjudicators are selected through a mechanism that does not depend on disputant parties’ wills. Moreover, their powers derive from a general mandate such as a treaty, and the outcome of their process aims to protect not only the parties’ interests but the public’s too. Comparatively, in arbitration, the parties set up the arbitration body after a dispute arises with the purpose of solving a particular issue and the mandate of the arbitral body depends on parties’ wills.Footnote 56 The parties also have control over the selection of adjudicators. For the purpose of this paper, the term ‘international courts and tribunals’ refers to all of the fundamentally independent international judicial bodies regardless of whether they are permanent or not. Therefore, the term refers to the bodies which are established by an international instrument, can issue binding decisions by referring to international law, follow pre-existing procedural rules on cases that at least include a state or an international organization, and are composed of independent judges.Footnote 57 Arbitral bodies are not generally included.

30.3.1 The ‘Uncoordinated Proliferation’

To understand the reasons for the concerns about ‘uncoordinated proliferation,’ it is essential to recognize the unique nature of the international legal system, the state of its main actors as well as their changing structure, and ultimately, why international courts and tribunals are uncoordinated. As a considerably new field of law, international law shows substantial differences compared to its national counterparts. Domestically, modern states usually aim to have a system of control that is unified, clear, and coherently law driven. Hence, most states have set up a legal hierarchy between norms, sources, bodies and procedures, usually through their constitutions. The structure of the international legal system is completely different. Unlike national legal systems, international law is a ‘horizontal’ system that, despite the recent codification trend, is still largely uncodified. This horizontality means, aside from jus cogens rules or erga omnes obligations,Footnote 58 there are no set of rules that have supremacy over the others, unlike a constitution in a national legal system.

Moreover, there is no formal hierarchy between the primary sources of international law set out in article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice (SoICJ). As a result, most of the bilateral and multilateral agreements or international and supranational organizations create their own autonomous and independent rules and dispute settlement means. Therefore, in the international legal system, it is possible to see the existence of more than one normative system regulating the same matter, or the existence of several courts and tribunals that have jurisdiction on same issues. This is a natural consequence of the decentralized nature of international law. The decentralized nature derives from the fact that international law has a ‘contractual’ characteristic rather than a ‘legislative’ one; international laws are usually created by bilateral and multilateral treaties or international customary law rather than by a designated primary law-making body.Footnote 59 This creates a decentralized legislative system that is usually unable to set a formal hierarchy between conflicting international norms or the jurisdictions of judicial bodies.

For a relatively long time, most have considered the aim of international law to be to create a united and harmonic legal order that is regulated by international legal rules and diplomacy.Footnote 60 In this regard, from its creation, some scholars have described the United Nations (UN) Charter as the ‘constitution of the world community’ and the UN as the body at the top of the international legal structure.Footnote 61 This was perhaps the outcome of comparing international law with its domestic counterparts and hoping for a similar structure for the international legal system. Great scholars like Kelsen or Lautherpact have pointed out the different nature of international law whilst defending the idea of a unified international legal system as a necessity. Neither lost faith in the possibility of having a unified and coherent international legal system.Footnote 62 However, both throughout the Cold war and after, their wish has not materialized. From this article’s point of view, it will not be possible to create a single and coherent international legal system in the near future. One of the main reasons of this is the impossibility of sustaining the traditional understanding of sovereignty. Of course, the main purpose of this paper is not to examine this topic, but in order to shed light on the other discussions in this chapter, this topic will briefly be explained.

In this regard, it no longer seems plausible to defend the traditional definition of state sovereignty, the so-called ‘Westphalian Model.’Footnote 63 Before the dilution of the traditional meaning of sovereignty, states were only limited within their domestic legal system by their own national law. According to the traditional definition, state sovereignty was absolute, unitary and legitimate. Therefore, no other actor could interfere with the internal matters of a nation. However, changes in, inter alia, technology, international relations and international order have transformed this notion.Footnote 64 States’ independence has shifted to interdependence and several developments have lead to this change.

Firstly, the establishment of international and supranational organizations has increased. These organizations, that mostly aim to provide stability to their members’ relationships, have set up normative standards and offered dispute settlement mechanisms. Today, for instance, members of the European Union (EU) are obliged to follow certain rules set by EU bodies, whilst at the same time, the World Trade Organization (WTO) asks members to conform to the standards set by the agreement. Of course, states are involved in these organizations through consent and they can choose to stay away; however, staying out of these organizations can be a big disadvantage. Thus, states prefer to be a part of organizations like the WTO or the EU for their own interest and allow these organizations to interfere with their domestic system either directly or indirectly.

Secondly, the universalization of human rights and the rising number of independent, non-governmental, monitoring organizations have started to impact the internal matters of states. Organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have aided in increasing the awareness of human rights and states’ treatment towards human rights, and UN bodies and the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) have set out obligations for states to promote human rights. Despite the fact that some human rights norms have no obligatory nature and suffer from a lack of enforcement, non-obligation of human right norms puts states in tough situations in front of the international community,Footnote 65 and as a result, influences their internal acts.

Thirdly, there is a growing consensus that state sovereignty does not preclude external intervention. Inter and inner state conflicts and internal humanitarian crises are often met with some form of action by members of the international community. In the recent Crimea crisis, the UN, the EU and the US got directly involved; states and international organisations such as the UN or the EU impose sanctions on states in attempting to deal with certain humanitarian crises occurring within states; and there is growing support in the international community for the concept of ‘humanitarian intervention.’

Fourthly, many issues now force states to be interdependent. States need one another on issues such as maximizing trade profits, protecting the environment or providing a minimum standard of human rights. This, coupled with the impact of globalization and liberalization, has lead the difference between the national and the international to become blurry. Nowadays, states need to be part of international agreements and organizations to both maximise and protect their benefits.

This impact on sovereignty makes it harder for a unified international legal system to exist because international relations are now occurring in a faster and more informal manner. The actors of international relations are not just states but include, inter alia, international organizations and non-governmental organisations, and the number of matters that each actor can act upon is wider because of this dilution in the traditional definition of state sovereignty. Therefore, the role of states in the international legal system is changing, and the actors of international law are diversified.Footnote 66

There are also other reasons why it does not seem possible for a single-handed or a hierarchical international legal system to exist. To begin with, the idea overlooks political reality. During the Cold War, it was believed that the polarized structure of the world was hindering establishment of a hierarchical structure governed by the UN. However, the rise of globalization, liberalism and the end of the East-west polarization did not change the lack of hierarchy and coherence. In the new era, the actors began competing with each other, tried to maximize their benefits and attempted to create competing normative systems.Footnote 67 Moreover, those who believed that the UN Charter would be a world constitution overlooked the source and nature of the Charter. The UN Charter was not derived from natural and legitimate sociological processes like domestic constitutions. Furthermore, with the exception of Article 103 of the UN Charter and its highly political and controversial relationship with Security Council resolutions, the UN has no formal supremacy over other international organizations or rules.Footnote 68 Also, other international rules do not take their legitimacy from the UN Charter. Therefore, the UN charter is not a constitution or constitution-like document but a pivotal multinational treaty.

Moreover, despite globalization and rising interdependence, there are still important economic, legal or social differences between different geographical regions. This prevents states from accepting similar norms about even universalised issues such as human rights. In this regard, one should accept that as long as the world does not become a more harmonized place sociologically, it is not likely to have a worldwide, hierarchal and unified normative system. Thus one should embrace the current structure of international order as well as the fragmented structure of international law.

Therefore, as a result of this decentralized structure of international law, there is no hierarchy or coherence between international courts and tribunals.Footnote 69 This lack of hierarchy and coherence had not drawn much attention until the late 20th, when the number of international courts and tribunals began to increase. The rise of compulsory jurisdiction and the rapid growth in the number of courts and tribunals has caused concerns about the uncoordinated multiplicity of judicial dispute resolution options.Footnote 70 Consequently, the possibilities of normative conflicts or the overlapping jurisdictions of courts and tribunals have created ‘the fear of chaos’ in international dispute resolution.

30.3.2 The Fear of Chaos

Due to its decentralized and horizontal nature, the international legal system is constituted of uncoordinated norms and bodies. Treaties and organizations tend to create or choose their own norms, procedures and dispute settlement means. These so-called ‘self-regulated’ regimes apply their own set of rules without any formal coherence with each other. In light of this nature, the recent rise in the creation of international courts and tribunals without any formal connection to each other has caused some anxieties. One scholar has even defined the uncoordinated and incoherent aspects of the international legal system and the international courts and tribunals as ‘anarchic.’Footnote 71 Thus, possibilities of normative, jurisdictional and jurisprudential conflicts between the uncoordinated courts and tribunals stand out as main concerns. The former ICJ president Guillaume emphasized these concerns;

Overlapping jurisdiction also exacerbates the risk of conflicting judgments, as a given issue may be submitted to two courts at the same time and they may hand down inconsistent judgments. National legal systems have long had to confront these problems. They have resolved them by, for the most part, creating courts of appeal and review. (…) The proliferation of international courts gives rise to a serious risk of conflicting jurisprudence, as the same rule of law might be given different interpretations in different cases.Footnote 72

Consequently, lawyers have questioned whether the rising number of international courts and tribunals pose a threat to the international legal system.Footnote 73 It has been argued that different interpretations on similar rules might threaten the perception of the existence of an international legal system and, if similar cases are not solved in the same means constantly, ‘the very essence of a normative system of law will be lost.’Footnote 74 In this context, conflicting interpretations of courts and tribunals might lead to the fragmentation of substantive international law and threaten the credibility of international law and its unity. Moreover, different pronouncements by courts and tribunals on the same issue of law might undermine the overall legitimacy of the international legal system and be harmful to the reliability of international adjudication.Footnote 75 This could potentially make the enforcement of decisions more problematic than ever. Former ICJ presidentsFootnote 76 and some authorsFootnote 77 have argued that the proliferation also threatens the role of ICJ as a primary judicial organ of the UN.

In this regard, the possibility of two major problems can be identified. Firstly, different international judicial bodies might produce different jurisprudences by interpreting the same rule of law differently. Secondly, two different international courts or tribunals might have jurisdiction on the same matter leading to different judgments on the same case. These possible problems will be examined in light of the aforementioned concerns by referring to some highly cited cases.

To begin with, international judicial bodies can interpret the same legal concepts or rules differently since there is no formal system between the international courts and tribunals or no stare decisis principle in international judicial dispute settlement. This means neither a judicial body’s own previous decisions nor other courts and tribunals pronouncements have binding force over a courts or tribunal’s decision. Consequently, it has been claimed that international law is facing danger of fragmentation. To illustrate the reality of this danger, scholars and the former ICJ presidents have cited some cases in which they claim this problem can be seen.

Perhaps the most cited example is the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia’s (ICTY) disagreement in the Tadic case with the ICJ’s previous Nicaragua pronouncement on an aspect of state responsibility.Footnote 78 In fact, this was not the first time that the ICTY had taken a different position to the ICJ. In 1996, while the ICJ stated, in its Nuclear Weapons advisory opinion, that an armed reprisal during an armed conflict should comply with the principle of proportionality,Footnote 79 in the Martic case the ICTY decided that armed reprisals are fully prohibited in international law.Footnote 80 Both bodies also took different approaches on the issue of whether it is possible to examine the legality of UN Security Council resolutions. While the ICJ avoided assessing of the legality of Security Council resolutions in the Lockerbie case,Footnote 81 in the Tadic case, the Appeal Chamber of the ICTY directly examined the legality of its own creation, which was through a Security Council resolution.Footnote 82

As mention, the decision that has been constantly referred to by scholars as well as by the former ICJ president Guillaume is the ICTY’s final judgement in the Tadic case. In its final decision, the Appeal Chamber of the ICTY explicitly referred to the ICJ’s Nicaragua decision and put forward a comprehensive analysis of the ICJ’s jurisprudence.Footnote 83 In Nicaragua, the ICJ had decided that the United States had no responsibility for the acts of the ‘contras,’ the acts themselves had violated international humanitarian law. In its reasoning, the Court stated that the fact that the United States trained and financed the ‘contras’ was not ground for its responsibility. According to the ICJ, in order to confer state responsibility, there must have been ‘effective control’ over the specific operation in which the violation was committed.Footnote 84 The ICTY disregarded the ICJ’s ‘effective control’ test by finding its reasoning unpersuasive. The ICTY stated that, at least for organized military groups, it was sufficient to have ‘overall control.’Footnote 85 This approach broadened the scope of responsibility with respect to states’ extraterritorial activities compared to the ICJ’s jurisprudence. In its Celebici decision, the ICTY explicitly stated that no hierarchical relationship existed between the ICTY and the ICJ, and therefore, the Court stressed that the ICTY is not bound by the ICJ’s jurisprudence.Footnote 86

Another example that has frequently been used to point out the ‘danger of fragmentation’ is the European Courts of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) judgement in the Loizidou v. Turkey case.Footnote 87 In that case, the ECtHR discussed the validity of the reservations Turkey made in its declaration accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court. Turkey argued the validity of its reservations under articles 26 and 45 of the Convention. These two articles correspond to article 36 of the ICJ Statute. An exactly similar situation has never arisen before the ICJ; however, in one of its advisory opinions, the ICJ stated that if any reservation were compatible with the object and purpose of the related convention, a reserving state would still be a party to the convention. Moreover, the Court pointed out that each reservation should be tested on its own standpoint.Footnote 88 However, in its Loizidou judgement, the ECtHR emphasized that it has a different legal nature to the ICJ:

(…) unlike the Convention institutions, the role of the International Court is not exclusively limited to direct supervisory functions in respect of a law-making treaty such as the Convention. Such a fundamental difference in the role and purpose of the respective tribunals, coupled with the existence of a practice of unconditional acceptance (…) provides a compelling basis for distinguishing Convention practice from that of the International Court. Footnote 89

The ECtHR found Turkey’s reservation impermissible by stating that provisions of the Convention should ‘be interpreted and applied so as to make its safeguards practical and effective.’Footnote 90 The ECtHR decision differed from the ICJ’s jurisprudence and took a more restrictive interpretation regarding reservations whilst pointing out the different nature of Convention and the ECtHR to the ICJ.

The second possible problem with the ‘uncoordinated proliferation’ is that different international courts and tribunals might have jurisdiction on the same matter, possibly leading to two or more judicial bodies making different decisions on the same issue. This potentially peculiar situation might endanger the legitimacy and enforceability of both verdicts. The Swordfish Case has been used as an example of this situation.Footnote 91 In the Swordfish case, Chile had closed its ports to the ships of the EU Member states and impeded EU vessels’ imports to Chile. The EU claimed that the act had violated both UNCLOS rules and the GATT. Therefore, the disagreement came before both of the ITLOS and a WTO panel. Footnote 92 However, these processes were both suspended due to a peaceful agreement taken between the involved states. This case exemplifies that the same type of situation may arise in the future. Whilst the WTO panel and the ITLOS would be applying different sets of rules and assessing the cases from different perspectives, the possibility of jurisdictional conflicts and different decisions being made still caused concerns.

All these cases are used to exemplify the risks of conflicting jurisprudences and jurisdictions of the courts and tribunals. It has been claimed that situations like these can harm confidence in the courts and tribunals, the coherence of the system as a whole and the legitimacy of the specific tribunal.Footnote 93 These concerns have some valid points, however, it is questionable whether the situation is as dramatic as described by the aforementioned writers. Is the danger as big as the former ICJ presidents described? Do we need to have ‘second thoughts’ when establishing new courts due to ‘proliferation’ concerns? The authors of the article believe that the complex adaptive properties of the international legal system might dispel these concerns.

30.4 Considering International Courts and Tribunals in the Context of Complex Adaptive Systems: Dispelling the Fears Regarding ‘Uncoordinated Proliferation’

As explained, the ‘uncoordinated proliferation’ of international courts and tribunals has led to some anxieties among international law scholars. Former ICJ presidents and some authors have stated that the ‘unity’ and ‘coherence’ of international law and international courts and tribunals might be threatened by the ‘proliferation.’Footnote 94 However, it is very doubtful whether unity or coherence has ever existed in the international legal system. If the words ‘unity’ and ‘coherence’ refer to a formal structure that has been designed and governed by rules and a set of bodies that have a definite hierarchical relationship, this type of a ‘unity’ or ‘coherence’ have never existed in the international legal system. On the other hand, if the words are intended to refer to a united mind, where all the parties have a similar approach and understanding towards the international legal system, this is also hard to find.

According to Frahm, the real hazard is to the ‘consistency’ and ‘cohesiveness’ of international law rather than to its ‘unity.’ He describes ‘consistency’ and ‘cohesiveness’ as the application and interpretation of international rules on the basis of legitimacy and formal standards.Footnote 95 However, it is also doubtful whether this kind of consistency and cohesiveness has ever existed.Footnote 96 In terms of substantive rules of international law, there are only a limited set of rules that have been universalized, namely erga omnes obligations and jus cogens rules.Footnote 97 There is also no uniformity in the procedural rules of the international institutions and bodies. Moreover, the relationship between the coherence of international law and its legitimacy is not linear. Therefore, the unity and coherence of international law is more likely an academic idea rather than a political reality.Footnote 98

In this regard, approaching the international legal system as a complex adaptive system allows one to better understand and assess the current structure of international courts and tribunals. This approach also leads to a better understanding regarding any future reforms. Thus, it shall be argued that international adjudicative bodies are more efficient as they become more compatible with the complex adaptive structure of the international legal order. Moreover, considering the aforementioned anxieties through the lens of complex adaptive systems theory enables further assessment to be made regarding these concerns.

To begin with, fear of a chaotic system due to uncoordinated proliferation and fragmentation seems unwarranted since the international legal system exists in the edge of chaos because of its dynamical, complex and decentralized nature. ‘Seeking ‘the edge of chaos’ is not seeking disorder or randomness but the right balance between order and flexibility. This perspective should give pause to lawyers, generally critical of fragmentation and decentralization, and intuitively in search of order and central authority’.Footnote 99 International law is derived from a pragmatic point of view. It does not have a constitution to reflect the common purpose of states or humanity. A higher organ, acting in a systematic manner, has not created international law. Instead, international law is created by several international agreements that cover different legal issues and different actors. If one uses the terminology of complex adaptive system theory to describe this, international law, as an outcome of the international legal system, is created and affected by the non-linear relationships of various heterogeneous actors, which have many different aims and interests. Therefore, the purpose of international courts and tribunals is not to maintain the coherence of international law, but to fulfil the roles that are laid out in their specific mandates. International actors are free to accept their jurisdiction as they please.

If a state or another actor needs to refer to an international judicial body at any point, it has total freedom to do so from the beginning.Footnote 100 Of course, if actors A and B bring their case before different courts at the same time, this might create conflicting interpretations on the same issue. However, international courts or tribunals either have a different ratione materiae, ratione loci or set of rules to apply. Thus, whilst different branches of international law will overlap, this does not make their perspectives the same.Footnote 101 Kingsbury argues that ‘the law and practice concerning provisional measures in international tribunals is somewhat chaotic (…)’ by exemplifying the different approaches of the ICJ, the ECtHR, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the ITLOS.Footnote 102 On the face of it, the anxiety regarding conflicting jurisprudences seems to be valid. However, international judicial bodies have different legal perspectives, mandates, subject matters and jurisdictions. In other words, they also reflect the heterogeneity of international legal order. Therefore, if the same matter goes to different bodies at the same time, each one of these bodies will apply a different set of rules and interpret the law according to their own mandates, traditions and aims.

The ICTY Trial Chamber stressed this issue while it was considering whether the ICTY should follow the ICJ’s jurisprudence. The Chamber stated that while the ICJ examined the state’s responsibility, the ICTY was examining the individual’s acts and responsibility. Thus, it rejected the existence of any real contradiction.Footnote 103 The Vienna Convention on the Law of TreatiesFootnote 104 already provides a basic set of rules to settle normative conflicts between treaties, such as lex specialis and lex posterior. In terms of jurisdictional conflicts, as long as courts and tribunals stay within their competence and apply traditional international legal reasoning, lack of formal unity or coherence does not pose a threat to the international legal order.Footnote 105 In addition, since none of the previous international court and tribunal decisions are formally binding, even for the same body, it is peculiar to expect jurisprudence not to conflict.

Moreover, due to the complex properties of the international legal system, establishment of a systematic and formal uniformity seems unlikely. This, however, does not pose a threat to the entire judicial system of international law. A totally fragmented system is unlikely because of the network connectivity and feedback loops present in the international legal system. Even if the sets of rules that courts and tribunals apply differ from one another, they are all part of the same root, international law. As Chaney states, international courts and tribunals generally have the same understanding about the core areas of international law.Footnote 106 There is no legitimate reason to claim that the international courts and tribunals will split up from the fundamental principles of international law. Therefore, the decentralized structure of international courts, tribunals and laws does not necessarily mean that the system is a totally fragmented one.

In addition, the inter-judicial dialogue between international courts and tribunals and between these bodies and national courts is growing. ‘The cases of institutional interactions typically involve the flow of information. Treaty and administrative bodies exchange information, both formally and informally, on shared substantive issues. They share reviews and lessons learned regarding their functioning and frequently consult each other on administrative or legal issues that arise.’Footnote 107 Despite the fact that international courts and tribunals are not bound by their own decisions or the decisions of others, they have the tendency to cite both it their judgements. This does not mean that courts and tribunals will follow one another’s jurisprudence, but this evidences that they recognize one another’s perspective. This is one of the instances of feedback loops present in international adjudication. The ICTY’s approach in the Tadic case is a perfect example of this. Whilst the ICTY did not follow the ICJ’s jurisprudence, it took it into consideration, discussed it and reasoned why the ICTY would follow a different path. Nowadays, international courts and tribunals are cognisant of one another’s views and decisions. Moreover, national courts have been citing international courts and tribunals’ views and application of the law more than ever.Footnote 108 Perhaps the most striking example of this was the citation of an ECtHR decision by a United States Court.Footnote 109

One should accept that international legal system is a pluralist one. There is diversity in the choices and approaches of different actors but, as stated above, the difference between the normative systems of the international law bodies and the difference in their interpretations and the interpretations of courts or tribunals only indicates a lack of formal hierarchy, but not a chaos or hazard in the system. As Burke-White puts it;

(…) the pluralist conception of the international legal system recognizes – and possibly thrives on – the diversity of the system. A wide range of courts will interpret, apply, and develop the corpus of international law. States will face differing sets of obligations that may even be interpreted differently by various tribunals and may at times conflict. Possibly most significantly, national and international legal processes will interact and influence one another, resulting in new hybrid procedures, rules, and courts. Yet, these developments will occur within a common system of international law engaged in a constructive and self-referential dialogue (…)Footnote 110

Burke-White’s comment covers some complex properties of the international legal system and international adjudication such as the diversity of the actors, laws and institutions; the decentralized composition of the system; and the non-linear interactions.

His comments also put forth another important complex property of the international legal system and international courts and tribunals. Similar to other decentralized systems, the international legal system has self-organization qualities that ‘have emerged through the interaction of its constituent components.’Footnote 111 ‘Centralized institutions (…) run counter to the principle of requisite variety, lack sufficient flexibility, and inhibit random mutations. On the contrary, decentralized institutions (…) have diverse components and are constantly changing through self-organization.’Footnote 112 Approaching the international legal system as a complex adaptive system allows us to better understand how the system generally operates, as a self-organizing system that is built up of many interacting actors, treaties, laws and institutions. It allows order to appear in the absence of any higher institution or power specifically designed to provide it. This therefore leads to a complex adjudicative structure and adjudicative institutions that also exhibit self-organizational properties.

International courts and tribunals emerge from a series of minor or major historical events. Despite the fact that international courts and tribunals are individually designed by humans rather than having transpired organically, the underlying reasons for their establishment are the many complex social and political interactions. Thus, there are certain indicators that international law and adjudication exhibits the same self-organized nature of the international legal system.

The first indicator of this self-organized nature is that, in some areas of international law such as international investment law or international environmental law, a substantive framework has not arisen from institutional decision-making or a central international agreement, but has arisen instead from several multilateral and bilateral agreements.Footnote 113 ‘The overall structure has incrementally evolved from, and is continuously shaped and reshaped by, the numerous decentralized decisions taken within individual institutions and the interaction effects arising therefrom.’Footnote 114 As a result, the system itself creates a decentralized and flexible dispute settlement understanding. Therefore, several different institutions and adjudicative and quasi-adjudicative bodies determine the substantive normative standards of these fields of international law. Of course, this set-up is not operative for some other fields of law such as human rights law or international criminal law since their normative nature does not feasibly lend itself to such a structure.

The second indicator is that multilateral regimes and their dispute settlement mechanisms have developed over time through trial and error.Footnote 115 Therefore, substantive laws, institutional powers, and jurisprudences have evolved through the agreements of several different actors in response to changes in the international legal system. To illustrate, the normative context of international criminal law has changed constantly over time. It is clear that the jurisprudence, substantive law and the structure of international criminal courts and tribunals (such as the Nuremberg Tribunal, ICTY, ICTR and ICC) are different from each other.Footnote 116 In this sense, the network connectivity of feedback leads to changes in the system. It does not matter that the change is deliberately imposed by parties rather than by an organic emergence. This is because various parties of the international community would have responded to feedbacks that they received from the system, and thus felt the need for a change in order to make the system more effective and stable. In other words, the parties did not create laws artificially but, instead, norms emerged from the societies and their interactions. For example, the concept of genocide was introduced to law only after World War IIFootnote 117 and the nexus between crimes against humanity and war was removed from substantive law only after the system identified that there was no need for a war to be occurring in order for a crimes against humanity to be committed.Footnote 118

The third indicator of this self-organization is that, ‘more subtle and policy-driven changes in existing law may arise through the process of interpretation reflecting the notion that treaties are living instruments that should be interpreted in light of contemporary conditions. Article 31(3)(c) of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides a powerful means in this regard. It requires that the interpreter of a treaty takes into account any relevant rules of international law applicable in relationships between the parties, and it may include other treaties, customary rules, or general principles of law. This dynamic approach to interpreting treaties provides additional adaptiveness in a way that builds a more coherent system.’Footnote 119 In fact, international courts and tribunals do not have the formal capacity to create or amend international law. However, it is certain that their interpretations on norms, in light of contemporary conditions, have an impact on both the development and creation of law (particularly customary international law).Footnote 120 There are some examples of this in international law’s history such as the introduction of erga omnes obligations by the ICJFootnote 121 or the emergence of the margin of appreciation doctrine in the jurisprudence of the ECtHR.Footnote 122 Thus, substantive law and the application of norms might be interpreted and re-interpreted by adjudicative bodies in order to adapt them to a current situation, and an emerging norm might have an impact on another actor, institution and the international legal system as a whole.

In light of all this, it can be argued that international adjudicative bodies should be designed to be more adaptive and flexible in order to be more efficient in a system that has complex properties. A complex adaptive system itself utilizes more adaptive institutions and shows resilience against rigidly designed ones. In this regard, it is not necessarily important whether international adjudicative institutions are organized around a single multilateral treaty, a central international organization, or by many different elements. What is important is whether adjudicative institutions and bodies are sufficiently flexible and are able to react to changes in the international order and legal system.

In this context, Kim and Mackey ask an important question while discussing the complexity of international environmental law; ‘each treaty or institution may be capable of learning from the experiences of its state members in applying negotiated rules, but what about the system of treaties and institutions as a whole?’Footnote 123 This question is also valid for this article and is the underlying reason as to why the international legal system and international law and adjudication have been considered together. International law and adjudication coevolves with international relations and the international legal system in order to respond to feedbacks and the interactions of its social environment and to be able to solve problems more effectively. Of course, as exemplified in the following paragraphs, the adaptive capacity of different international institutions and adjudicative bodies varies since their legal aims and norms are different. However, in general, claiming that there is a completely distinct institution or legal framework to the all parts of the international legal system is not accurate. A change in international law or the legal order can have an impact on other actors and institutions. Disagreements on international labour law issues between the US and China might have an impact on the substance of an international investment agreement, and the emergence of a concept in international environmental law can affect international human rights or international trade law jurisprudences.

Fear of an inefficient system due to fragmented international law and the uncoordinatedly proliferated courts and tribunals appears to be an inaccurate consideration in the light of complex adaptive systems theory. The proliferation of institutions and their decentralized nature in the international legal system does not necessarily imply anarchy or chaos. On the contrary, in a complex adaptive system, more centralization can have negative impacts on the adaptation capacity of the institutions and laws, as well as on their effectiveness.

The ICJ and the ITLOS might be the best examples of adjudicative results stemming from ‘deeply pathological regimes riddled with birth defects in need of drastically more coherence and structure’Footnote 124 The establishment of these international courts and tribunals was an outcome of the idea of controlling the system using a top-to-bottom approach and creating a unified international dispute understanding. The premise of the ICJ was for it to be a ‘world court’ under the organization of the UN, with the capacity to solve any type of disagreement between its parties. However, to date, only 71 states have recognized the jurisdiction of the Court as compulsory, and most of these states have made many reservations to their declarations.Footnote 125 The caseload of the court has always been an issue; the ICJ has only heard 2.4 cases per year since its establishment.Footnote 126 In addition, the implementation of the Court’s judgments has proved to be problematic in cases such as Tehran Hostages Footnote 127 or Nicaragua.Footnote 128 In a similar vein, the ITLOS has suffered from very comparable problems. While it was created by the mandate of the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, it has been referred to rarely; only 22 cases have ever been submitted to the ITLOS, of which most are in regards to prompt release or provisional measures.Footnote 129

Comparatively, when adjudicative regimes are more decentralized and flexible, they become more efficient and successful in terms of their caseload and their ability to solve the disputes. For instance, the ECtHR is also an outcome of a pivotal multinational treaty like ITLOS. However, certain adaptive properties of the ECtHR make it much more effective in terms of caseload and the enforcement of its decisions. For example, in response to feedbacks from the system, parties of the ECHR constantly amend law via protocols to make the court more effective. Moreover, the ECtHR has developed an important jurisprudence, the so-called ‘margin of appreciation’ doctrine. This doctrine refers to ‘the space for manoeuvre that the Strasbourg organs are willing to grant national authorities, in fulfilling their obligations under the Convention.’Footnote 130 It allows the ECtHR to take into account the fact that the Convention will be interpreted differently in different member states due to their varying judicial and sociological structures and public interests. Today, the ECtHR is accepted as being one of the most efficient international courts.

In the some other areas of international law, complex and adaptive properties are more prominent. For example, in international investment law, thousands of treaties, customary laws, national laws, agreements and arbitration awards co-exist without a central mechanism or multinational treaty controlling the system.Footnote 131 This decentralized structure and constant interaction between various actors enables the law to constantly adapt itself in reaction to the needs of all the components.Footnote 132 Of course, the very nature of this field of international law is different. It would not be suitable to create an international investment law like dispute settlement understanding for international human rights, international criminal law or the law of the sea since these fields require different approaches regarding their institutions and some of their significant norms are not flexible. Nonetheless, it still seems vital to make these laws and institutions as adaptive as possible to the complex nature of the international legal system in order to make them more efficient.

Nevertheless, this varied nature of the various international adjudicative bodies is a natural consequence of the fact that the international legal system operates in the edge of chaos and is constantly seeking the perfect balance between order and flexibility. Parties of international adjudication are looking to maximize their interests and gain more control over dispute settlement processes. At the same time, there is a need for order and predictability in the international legal system to avoid chaos. Thus, whilst some international adjudicative bodies can strike this balance such as the WTO dispute settlement mechanisms or ICSID arbitrations, international bodies, like the ITLOS, which try to create a rigid top-to-down mechanism, suffer from stagnation and deadlock. As it is stated by Pauwelyn ‘resilience of the system questions the absolute need for a controlling multilateral institution or dramatically more centralization’Footnote 133 Therefore, in terms of international legal system and its sub-part international adjudication, seeking to continue operating in the edge of chaos is more effective and sustainable in the long run.

In light of the above analysis, the benefit international law and adjudication gains from highlighting the complex adaptive properties of the international legal system can be seen. Despite the fact that the international legal system has a fragmented structure in terms of its institutions and norms, it is not a completely chaotic, randomly organized collection of norms and institutions. On the contrary, this decentralized composition of norms and institutions creates a more flexible and effective system for the interactions between equally sovereign independent states and between them and other actors of international relations. ‘Change in social systems is very often the specific intent of human intervention, in which case knowing how the system responds to change should be an important factor in the design of the instrument of change.’Footnote 134 Given this, international law and its courts and tribunals should be designed around the complex adaptive system properties of the international legal system.

As Belcher emphasises, ‘in the consideration of the agents that comprise the legal system where a legal reform program can go awry – most commonly as an error of exclusion as there are numerous secondary and tertiary interested parties that are frequently overlooked during reforms.’Footnote 135 ‘Law, as a complex adaptive system, coevolves with the social systems it aims to regulate, and thereby induces changes on itself. (…) therefore, the theory of law’s complexity counsels us to design law to think like a complex adaptive system.’Footnote 136 Thus, various agents and possibilities should be considered when international law is designed. To this end, organizational ties should be strengthened, such as the duty to cooperate and coordinate among treaty bodies or other institutional entities. Moreover, international courts and tribunals both in terms of their procedures and jurisprudence should search for the right balance of stability and flexibility.

For a long time, international lawyers have complained about the weak nature of the international judiciary.Footnote 137 Therefore, it is somehow peculiar to witness these ‘proliferation’ discussions. The ‘proliferation’ of international courts and tribunals is not a real danger, but instead an opportunity to strengthen the international legal system. As Buergenthal states ‘the proliferation of international tribunals with specialized and regional competence has in recent decades enabled governments to experiment with and observe the effects of international adjudication involving states and their acceptance of the jurisdiction of international tribunals.’Footnote 138 In this sense, the complex adaptive properties of the international legal system indicates that different ideas and experiments are not a hazard for international law, but an opportunity to improve normative systems or to create better ones.

Notes

- 1.

Belcher, M., and Newton, J. (2005). ‘International Legal Development: A Complex Problem Deserving of a Complex Solution and Implications for the CAFTA Region’, 12 Sw. J. L. & Trade Am. 189, p. 190.

- 2.

Statement of Judge Stephen M. Schwebel, President of the International Court of Justice, to the Plenary session of the General Assembly of the UN 26.10.1999, http://www.icj-cij.org/court/index.php?pr=87&pt=3&p1=1&p2=3&p3=1&PHPSESSID. Accessed on 07.08.2014; Statement of Judge Gilbert Guillaume, President of the International Court of Justice, to the UN General Assembly of 26.10.2000, http://www.icj-cij.org/court/index.php?pr=84&pt=3&p1=1&p2=3&p3=1. Accessed on 07.08.2014.

- 3.

For example. Born, G., (2012). ‘A New Generation of International Adjudication’, 61 Duke Law Journal, pp. 858–864, http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1523&context=dlj. Accessed on 12.08.2014.

- 4.

Belcher, ‘International Legal Development’, supra note 1, p. 193.

- 5.

Ruhl, J. (2008). ‘Law’s complexity: A premier’, 24 Georgia State University Law Review, p. 889.

- 6.

Ruhl, J. (1997). ‘Thinking of Mediation as a Complex Adaptive System’, Brigham Young University Law Review, p. 777.

- 7.

Belcher, ‘International Legal Development’, supra note 1, p. 194.

- 8.

Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: A guided tour, Oxford: Oxford University Press (2009). p. 13.

- 9.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. White River Junction: Chelsea Green. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. pp. 2–4.

- 10.

Belcher, ‘International Legal Development’, supra note 1, p. 194.

- 11.

Hornstein, D. (2005) ‘Complexity Theory, Adaptation, and Administrative Law’, 54 (4) Duke Law Journal, pp. 913–960.

- 12.

Ruhl, ‘Law’s Complexity’, supra note 5, p. 904.

- 13.

Miller, J. and Page, S. (2007). Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life, Princeton University Press, p. 9.

- 14.

Ruhl, ‘Law’s Complexity’, supra note 5, p. 891.

- 15.

Belcher, ‘International Legal Development’, supra note 1, p. 198,199.

- 16.

Pauwelyn, J. (2014). ‘At the Edge of Chaos? Foreign Investment Law as a Complex Adaptive System, How It Emerged and How It Can Be Reformed’ 29 ICSID Review, p. 392.

- 17.

See. Gross, J., McAllister, R., Abel, N., Smith, D., and Maru, Y. (2006). ‘Australian rangelands as complex adaptive systems: A conceptual model and preliminary results’, 21 Environmental Modelling & Software, pp. 1264–1270.

- 18.

See Generally, Arthur, B., Durlauf, S., and Lane, D. (1997) (eds.), ‘The Economy as an Evolving Complex System II, Introduction: Process and Emergence in the Economy’, Addison-Wesley, http://tuvalu.santafe.edu/~wbarthur/Papers/ADL_Intro.pdf. Accessed on 07.08.2014.

- 19.

Pauwelyn, ‘At the Edge of Chaos?’, supra note 16, p. 393.

- 20.

Newman, M. (2001). ‘Complex systems’, 79 American Journal of Physics, p. 800.

- 21.

Belcher, ‘International Legal Development’, supra note 1, p. 195.

- 22.