Abstract

Workplace bullying is an anti-social behaviour which is defined as continuous harassment or “mobbing” of individual employee experienced for a relatively longer period of time. This may take several forms such as constant abuse, offensive remarks or teasing, ridicule, social exclusion, harassment, physical violence etc. The situation may be damaging to the wellbeing and job performance of the employee. However, if the organisation provided necessary support to the employee the effect of bullying could be mitigated. The paper examines these issues in selected Malaysian organisations. A sample of 231 employees representing different industry, size, gender, age, experience and job position responded to a self-rated questionnaire which measured the study variables, namely workplace bullying, psychological strain, self-rated job performance, and organisational support. Result indicated that nearly 14 % employees faced bullying incidents either weekly or daily. Such incidents resulted in higher psychological strain and lower job performance. Role of psychological support was positive in promoting performance and reducing strain.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Workplace bullying

- Workplace negative acts

- Anti-social work behaviour

- Psychological strain

- Job performance

1 Introduction

Workplace bullying is considered a severe form of anti-social behaviour. According to O’Driscoll et al. (2011), this behaviour is a major issue among employees and in organizations. Bullying can be identified by the occurrence of harmful physical or verbal behaviour that is repeated regularly. The individual or group being targeted is usually less powerful than the bully and lacks the ability to take a defensive position. Workplace bullying can occur in many forms, and can involve the use of insulting comments, yelling, screaming, and cursing. According to a survey one in six workers in the United States had been a victim of bullying in the previous year. Statistics also show that 81 % of bullies in the workplace are bosses and that the targets of bullying are usually women (Greenberg 2011).

According to Namie (2003), research about bullying was first initiated in the 1980s by a German psychiatrist, Heinz Leymann, who created an anti-bullying movement. Prior to the coining of the term “workplace bullying” in 1992 by British journalist Andrea Adams, workplace bullying was referred to as “mobbing”. LaVan and Martin (2008) mentioned that workplace bullying had been studied under a variety of terms, including employee abuse, workplace aggression, victimization, interpersonal deviance, social undermining, and workplace incivility.

The phenomenon of workplace bullying is responsible for many negative consequences, ranging from mild to severe harm, to physical violence that can result in death. Einarsen et al. (2003) reported that workplace bullying is a more crippling and devastating problem for employees than all other kinds of work-related stress put together. O’Driscoll et al. (2011) conducted a survey of over 1,700 employees of 36 organisations in New Zealand and found a strong relationship between bullying and strain, reduced well-being, reduced organisational commitment, and lower self-rated performance.

Although the prevalence of workplace bullying in various countries has been explored in several studies, the majority of these studies have been conducted in Scandinavia and other European countries (O’Driscoll et al. 2011). There is little evidence from countries such as Malaysia. The present study, therefore, intends to explore this issue in the Malaysian workplace.

1.1 What Is Workplace Bullying?

Workplace bullying has been defined in several ways. Leymann (1996) defined it as psychological terror or mobbing in working life that involves hostile and unethical communication, which is directed in a systematic way by one or a few individuals mainly towards one individual who, due to mobbing, is pushed into a helpless and defenceless position, being held there by means of continuing mobbing activities. Leymann further maintains that such behaviour, over a long duration, causes psychological, psychosomatic, and social misery.

Einarsen et al. (2003) posited that bullying at work means harassing, offending, or socially excluding someone, or negatively affecting someone’s work tasks. In order for the bullying (or mobbing) label to be applied to a particular activity, interaction or process, the action has to occur repeatedly and regularly (e.g., weekly) and over a period of time (e.g., 6 months). Bullying is an escalating process during the course of which the person confronted ends up in an inferior position and becomes the target of systematic negative social acts. A conflict cannot be called bullying, however, if the incident is an isolated event, or if two parties of approximately equal “strength” are in conflict.

According to Namie (2003) regardless of how bullying is manifested, through either verbal assaults or strategic moves to render the target unproductive and unsuccessful, it is the aggressor’s desire to control the target that motivates the action. Usually the person that the victim reports to (the boss) is the bully. Some common features of bullying in organizations include multiple negative acts and repeated forms of abuse, persisted abuse (over a period of 6 months or more), and involves power distance or disparity between the bully and the victim (Mikkelsen and Einarsen 2001; Salin 2001; Hoel et al. 2001; Zapf et al. 1996).

Research shows that bullying does not necessarily involve people from different genders or races. In fact, most reported bullying incidents involve people of the same sex and gender as the victim. Only 25 % bullying cases involve perpetrators of a different gender (Namie 2003). Namie observed that the characteristic common to all bullies is that they are controlling competitors who exploit their cooperative targets. Most bullies would stop if the rules changed and bullying was punished.

Few studies have addressed the issue of this anti-social behaviour in Malaysia. Patah et al. (2010) conducted a study on workplace bullying experiences, emotional dissonance and subsequent intentions to pursue a career in the hospitality industry. The study involved Malaysian diploma holders training at different hotels in Malaysia. Findings showed the significant impact of workplace bullying on the trainees’ subsequent career intentions and the emotional dissonance of their experiences. Another study by Yahaya et al. (2012) investigated the impact of workplace bullying on work performance in a manufacturing company. They reported significant relationship. Writing an essay on this subject in a Malaysian newspaper, Yeen (2012) posited that victims of workplace bullying in Malaysia may not have physical injuries, but they are suffering from pain that runs inside them. The situation at the workplace, the author mentions, is very similar to the typical schoolyard where little kids are bullied. Yeen opined that Malaysians in the workplace can become targets for bullies if they have at least one vulnerability that can be exploited, are different from others, are conscientious, quiet achievers, good at their job, are agreeable and well-liked, show independence of thought or deed, get more attention from others than the bully does, have inappropriate social skills and have annoyed the bully, are unassertive and prefer to avoid conflict, have a dispute with the bully, and are just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

1.2 Workplace Bullying and Psychological Strain

Previous researchers have agreed that workplace bullying is a major stress factor and it can have negative consequences on employees’ health (Bjorkqvist et al. 1994; Einarsen and Raknes 1997; Einarsen et al. 1996; Niedl 1996; O’Moore et al. 1998; Vartia 2001; Zapf et al. 1996). Agervold and Mikkelsen (2004) reported that employees may experience symptoms of anxiety, irritability and depression as health effects. In worst cases employees may develop symptoms similar to Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Leymann 1996). Namie (2003) also reported that the WBTI 2003 survey, aimed at measuring the psychological status of bullied employees, showed shocking results as effects of bullying range from severe anxiety (76 % prevalence), disrupted sleep (71 %), loss of concentration (71 %), PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder, 47 %), clinical depression (39 %), and panic attacks (32 %). All studies seem to suggest that experiences of bullying at work may negatively affect employee mental health and well-being. As such we hypothesised that:

H/1

Workplace bullying positively affects employees’ psychological strain.

1.3 Workplace Bullying and Job Performance

Workplace bullying has damaging effect on employees’ job performance as well. The more severe bullying is, the more psychological strain it causes, the worse job performance is. Studies suggest that the decreased job performance has an impact on job satisfaction and productivity. Fisher-Blando (2008) explained that bullying has a negative effect on how employees perform their jobs, which also has a negative impact on the employees’ morale and the financial performance of the organization. Namie (2003) also added that workplace bullying is very costly for the organization as bullied employees, who happen to be talented, develop job dissatisfaction and eventually leave the organization, so the rates of turnover will increase. Another study by Lutgen-Sandvik et al. (2007) found out that the degree of workplace bullying is negatively correlated with job satisfaction and overall job performance rating. Therefore the following hypothesis was developed.

H/2

Workplace bullying negatively contributes to employees’ job performance.

1.4 Workplace Bullying and Role of Organizational Support

The construct of perceived organizational support includes employees’ belief that the organization values their contributions, efforts, and well-being (Chen et al. 2009). The organization is perceived to fulfil the socio-emotional needs of its employees. There are evidences from work stress literature that social support at the workplace as well as organisational support contribute to increased job satisfaction, more positive mood, reduced stress, increased affective organizational commitment, increased performance, reduced turnover (O’Driscoll et al. 2011; House et al. 1988; Nahum-Shani and Bamberger 2011). Therefore, we hypothesised that:

H/3

Bullying at the workplace is negatively related to perceived support from the organization.

Furthermore, it was expected that effect of bullying on employees’ psychological strain as well as performance will be reduced if the organisation provides adequate support to the employees in terms of valuing their contribution and well-being. It was, therefore, hypothesised that:

H/4

Organisational support is positively associated with employees’ performance and negatively with psychological strain.

2 Method

2.1 Instruments

Following instruments were used to measure the study variables.

-

(a)

Workplace bullying was measured using the 22 revised version of Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ-R) by Einarsen (Hauge et al. 2007). The 22 items describe negative behaviours employees may encounter at the workplace. For instance, “Being ignored or facing a hostile reaction when you approach”. The responses vary from 1 (never) to 5 (daily). The instrument has been widely used and has been recognized as a reliable and valid measure of bullying construct (See Carroll and Lauzier 2014).

-

(b)

Psychological strain was measured using the 12 items of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) developed by Goldberg (1972). The respondents had to select how often they experienced the 12 items of psychological symptoms such as “Feeling unhappy and depressed”. Higher score on the instrument indicated greater strain. The scale is regularly used in occupational strain studies (O’Driscoll et al. 2011)

-

(c)

Organisational Support was measured by eight items adopted from scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (1986). Example of the measurement items in the scale: “The organization cares about my general satisfaction at work”. The test has four positively worded and four negatively worded items. The negative items were reverse-scored so that higher score indicated greater perceived support from the organization.

-

(d)

Self-rated job performance was measured by a single item scale developed by Kessler et al. (2003). Respondents are asked to rate themselves on a scale of 1–10 to indicate how well have they performed their job over the last 4 weeks?

The questionnaires were conveniently distributed to the employees working in different organisations through personal contacts as well as using online survey. A total of 231 usable ones were returned. Respondents were ensured about the confidentiality as well as anonymity to ensure their frank response on the questionnaire. Some demographic details were also collected.

2.2 Respondents’ Profile

Good number of respondents worked in customer service (18.2 %); the smallest group belonged to health institutions and personal care (3.5 %). Gender wise distribution showed a higher percentage of females (56.3 %) compared to males (43.7 %). Age-wise the largest number (42.9 %) fell into the age group of 21–30 years and only 5.6 % were above 51 years. In terms of Job levels 27.3 % were executives, 26.4 % were managers and 1.7 % were consultants. Majority of them (43.3 %) had the work experience between 6 and 10 years. Only 4.8 % had a work experience of 21 years and above.

3 Results

3.1 Frequency of Negative Acts

The frequency analysis revealed various forms of negative acts faced by employees in different frequencies. Most employees never got any negative behaviour at their workplace. However, there were number of instances where the encounters were either now and then, monthly, weekly and in some cases daily. Table 1 displays the frequencies.

Most employees never got any negative behaviour at their workplace. However, there were good number of instances where they reported facing various forms of negative acts now and then, such as, someone withholding information which affected performance, spreading gossips, being shouted at or becoming target of anger, opinion being ignored, and getting tasks with unreasonable deadlines. Some admitted that they have received threats of violence or physical or actual abuse at work. In terms of the incidents occurring monthly 25 % reported that they were being ordered to do work below their level of competence, 29 % said that gossip was being spread about them, 25.5 % were being reminded of their errors and mistakes, and 28.1 % were being pressured to not claim something to which by right they were entitled to.

Some common negative behaviour faced on weekly basis was: someone withholding information which affects performance (16.9 %), being ordered to do work below the employee level of competence (18.6 %). Another 19.5 % respondents said that they have been insulted and offended with remarks regarding their person, attitude, or private life.

Being bullied on daily basis is the most severe kind and it could leave serious damages. Although the low percentages indicated that only a handful of employees were getting bullied daily, it does not mean they should be ignored. This is a serious problem, and whoever is responsible should be stopped and punished. 5.6 % of the respondents said that key areas of responsibility have been removed or replaced with more trivial or unpleasant tasks, and gossip was being spread about them. 5.2 % of them reported receiving insulting behaviours daily.

3.2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics and coefficient of correlations. Results indicated good reliability of instruments used in the study. Correlations suggested that workplace bullying was positively associated with psychological strain (r = 0.42) and negatively with perceived organizational support (r = −0.68). Also, bullying was negatively associated with self-rated job performance (r = −0.52). Organizational support, on the other hand, was negatively related to psychological strain (r = −0.35) and positively correlated with self-rated job performance (r = 0.35). The correlations were in the hypothesized direction.

O’Driscoll et al. (2011) argued that the frequency of bullying encounters may not necessarily indicate the severity of a negative act. Even a less frequent bullying action may have a strong impact on the employees. Therefore, to measure the relative contributions of each negative act to employees’ performance and strain, multiple regressions were performed. Multicoliniarity diagnostics were performed and no issue was found as VIF indices were within acceptable range. A Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of less than ten is considered acceptable value to rule out multicoliniarity of the independent variables in equation (Pallant 2010). Results are entered in Table 3.

Regression analysis yielded three items of NAQ contributing negatively to employees’ performance and eight items contributing positively to psychological strain. Negative acts that resulted into lower self rating of performance included someone withholding information, opinion being ignored, and unreasonable deadlines. Similarly, acts that resulted in higher strain included being humiliated or ridiculed, insulting, offensive remarks, being shouted at or being target of spontaneous anger, repeated reminders of mistakes, repeated criticisms, practical jokes, and excessive teasing and sarcasm. Overall negative acts explained 34 % of the variance in performance and 30 % in psychological strain and supported hypotheses 1 and 2 of the study.

3.3 Bullying and Organisational Support

The NAQ items were also regressed on perceived organisational support to test hypothesis 3 which expected negative relationship between the two. Table 4 displays the result.

The findings supported hypothesis 3. Out of 22 items of NAQ, 12 were found to be negatively associated with organisational support. Together such experiences explained 58 % of the variance. To test hypothesis 4 a simple regression analysis was performed to predict the two dependent variables, i.e., performance and strain from organisational support. Analysis showed positive contribution (β = 0.35, P < 0.000) to self-rated job performance and negative contribution (β = −0.16, P < 0.01) to psychological strain.

4 Discussions and Conclusion

The study proposed to examine the situation on workplace bullying and how frequently various negative acts occur in workplaces in Malaysia. The study objectives also included examining the effects of bullying on psychological strain, perception of organisational support, and self rating of performance. It was expected that bullying will positively affect psychological strain and negatively affect performance as well as perceived organisational support. Also, it was expected that organisational support will mitigate psychological strain and facilitate performance.

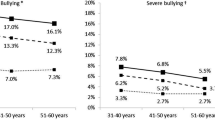

The combined frequency of negative acts experienced on a weekly or daily basis (to qualify as being bullied) suggested a score of 14.07 %. This is the figure that has been reported in other studies as well. For example Nielsen et al. (2010) reported an overall 14.6 % of employees being bullied after conducting a meta-analysis of 86 studies across several countries. Some common negative behaviour faced on weekly and daily basis were: withholding information which affected performance (18.6 %), being ordered to do work below the level of competence (21.2 %), having key areas of responsibility removed or replaced with more trivial or unpleasant tasks (20.8 %), spreading gossip about you (18.6 %), being ignored or excluded (18.2 %), repeatedly criticized (21.6 %) and being insulted and offended with remarks regarding their person, attitude, or private life (19.5 %).

It was also suggested that (e.g., O’Driscoll et al. 2011) even a less frequent negative encounter may have profound psychological impact on employees that may reduce their motivation to work and cause distress. We, therefore, performed multiple regression analysis to examine the contribution of each of the 22 negative acts (included in the NAQ measure) on two the outcome variables, namely, self-rated job performance and psychological strain. The findings showed that more negative acts contributed to strain than to performance. Several negative encounters caused significant psychological distress; however, three acts of others significantly reduced their performance. As reported earlier these acts included: withholding of information that affected employees’ performance, their opinion being ignored, and unreasonable deadlines. Among the acts that caused strain included task given with unreasonable deadlines, being humiliated or ridiculed in connection with work, getting personal insulting or offensive remarks, being shouted at or being target of anger, repeated reminders of errors and mistakes, repeated criticism of work effort, practical jokes carried out by unfriendly colleagues, and being subject of excessive teasing or sarcasm.

The result examining the effect of bullying on self rated job performance and psychological strain supported our hypothesis. The analysis also suggested a significant negative contribution of bullying experiences on perceived organisational support. On the other hand organisational support was negatively associated with strain and positively with performance. As posited by Chen et al. (2009), perceived organizational support indicates employees believe that the organization values their contributions, efforts, and well-being. In return employees enjoy their work, show work commitment and better performance.

Overall the findings were in line with previous studies conducted in other places which suggested the negative effects of workplace bullying on employees’ performance, job satisfaction, morale, and intention to stay with the organisation (Fisher-Blando 2008; Namie 2003; Lutgen-Sandvik et al. 2007).

4.1 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

The study has few limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small thus limiting the possibility of any adequate generalisation of results. Furthermore, data need to be collected from a well-designed sampling framework that adequately represents employees from different sectors and industry as well as better representations of employees at different levels within the organisation. Also the cross sectional design of the study puts limitation on causal explanation. Moreover, objective of the study should have included coping strategies that employees develop in situations where they are frequently subjected to negative acts, as well as organisational initiatives to mitigate the effects of such acts. Future studies are recommended to examine these issues.

References

Agervold, M., & Mikkelsen, E. G. (2004). Relationships between bullying, psychosocial work environment and individual stress reactions. Work and Stress, 18(4), 336–351.

Bjorkqvist, K., Osterman, K., & Hjelt-Back, M. (1994). Aggression among university employees. Aggressive Behavior, 20(3), 173–184.

Carroll, L. C., & Lauzier, M. (2014). Workplace bullying and job satisfaction: The buffering effect of social support. Universal Journal of Psychology, 2(2), 81–89.

Chen, A., Eisenberger, R., Johnson, K. M., Sucharski, I. L., & Aselage, J. (2009). Perceived organisational support and extra-role performance: Which leads to which? Journal of Social Psychology, 149(1), 119–124.

Einarsen, S., & Raknes, B. I. (1997). Harassment in the workplace and the victimization of men. Violence and Victims, 12(3), 247–263.

Einarsen, S., Raknes, B. I., Matthiesen, S. B., & Hellesoy, O. H. (1996). Bullying at work and its relationships with health complaints: Moderating effects of social support and personality. Nordisk Psykologi, 48, 116–137.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). The concept of bullying at work: The European tradition. In S. Einasen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse at workplace: An international perspective in research and practice (pp. 3–30). London: Taylor & Francis.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507.

Fisher-Blando, J. L. (2008). Workplace bullying: Aggressive behavior and its effect on job satisfaction and productivity. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Phoenix.

Goldberg, D. P. (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greenberg, J. (2011). Behavior in organizations (10th ed.). London: Pearson.

Hauge, L. J., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2007). Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work and Stress, 21(3), 220–242.

Hoel, H., Cooper, C. L., & Faragher, B. (2001). The experience of bullying in Great Britain: The impact of organizational status. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 443–465.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationship and health. Science, 241, 540–545.

Kessler, R. C., Barber, C., Beck, A., et al. (2003). The world health organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ). Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45(2), 156–174.

LaVan, H., & Martin, W. M. (2008). Bullying in the U.S. workplace: Normative and process-oriented ethical approaches. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 147–165.

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Psychology, 5(2), 165–184.

Lutgen-Sandvik, P., Tracy, S. J., & Alberts, J. K. (2007). Burned by bullying in the American workplace: Prevalence, perception, degree and impact. Journal of Management Studies, 44(6), 837–861.

Mikkelsen, E. G., & Einarsen, S. (2001). Bullying in Danish work-life: Prevalence and health correlates. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 393–413.

Nahum-Shani, I., & Bamberger, P. A. (2011). Explaining the variable effect of social support on work-based stressor-strain relations: The role of perceived pattern of support exchange. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 114, 49–63.

Namie, G. (2003). Workplace bullying: Escalated incivility. Ivey Business Journal, 68(2), 1–6.

Niedl, K. (1996). Mobbing and well-being: Economic and personal development implications. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 239–249.

Nielsen, M. B., Mathiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2010). The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and organizational Psychology, 83(4), 955–979.

O’Driscoll, M. P., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Bentley, T., Catley, B. E., Gardner, D. H., & Trenberth, L. (2011). Workplace bullying in New Zealand: A survey of employee perception and attitudes. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 49(4), 390–408.

O’Moore, M., Seigne, E., McGuire, L., & Smith, M. (1998). Victims of bullying at work in Ireland. The Journal of Occupational Health and Safety: Australia and New Zealand, 24(3), 569–574.

Pallant, J. (2010). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS. New York: McGraw Hill International.

Patah, M. O., Abdullah, R., Naba, M. M., Zahari, M. S., & Radzi, S. M. (2010). Workplace bullying experiences, emotional dissonance and subsequent intentions to pursue a career in the hospitality industry. Journal of Global Business and Economics, 1(1), 15–26.

Salin, D. (2001). Prevalence and forms of bullying among business professionals: A comparison of two different strategies for measuring bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 4(4), 425–441.

Vartia, M. (2001). Consequences of workplace bullying with respect to the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environment and Health, 279(1), 63–69.

Yahaya, A., Ing, T. C., Lee, G. M., Yahaya, N., Boon, Y., & Hashim, S. (2012). The impact of workplace bullying on work performance. Archives Des Sciences, 65(4), 18–28.

Yeen, O. I. (2012). December 10. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from http://thestar.com.my/lifestyle/story.asp?sec=lifefocus&file=/2012/12/10/lifefocus/12373851

Zapf, D., Knorz, C., & Kulla, M. (1996). On the relationship between mobbing factors and job content, social work environment and health outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5, 215–237.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Hassan, A., Al Bir, A.T.S., Hashim, J. (2015). Workplace Bullying in Malaysia: Incidence, Consequences and Role of Organisational Support. In: Bilgin, M., Danis, H., Demir, E., Lau, C. (eds) Innovation, Finance, and the Economy. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15880-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15880-8_3

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-15879-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-15880-8

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)