Abstract

This contribution aims to broaden our understanding of factors affecting innovativeness of successors in family businesses in transition economies. In-depth literature review was conducted and three main constructs were identified as having considerable impact on successors’ innovativeness and that are: entrepreneurialism, knowledge transfer and creation, and social capital. We applied a multiple-case study approach and the main research findings of ten cases of Slovenian family businesses are discussed. We developed six propositions that provide a basis for further empirical testing of factor influencing successors’ innovativeness and innovation ability of family businesses in transition economies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Family business

- Succession

- Founder

- Successor

- Innovativeness

- Social capital

- Tacit knowledge

- Knowledge transfer

- Transition economy

- Slovenia

1 Introduction

While family businesses and succession have become an interesting subject of research in the recent years, and since 1990 the interest in the field has grown (Chirico, 2008), the question of smaller family firms (SFF) ability for innovation processes remains relatively unexplored (Chrisman, Chua, & Sharma, 2003). SME’s, innovation marketing and excellent research systems are drivers of innovation growth in EU. SFF represent an important share in the structure of all firms; over 70 % of all firms worldwide, according to Mandl (2008). Thus increase of their innovativeness is crucial for development of EU and Slovenia, which is one of the innovation followers with a below average performance, as an innovative society.

In our contribution we study SFF on a case of transitional economy in Slovenia. Although Slovenia, from a legal prospective is not in transition anymore, we believe, that from economic-development aspect it can be viewed as a transitional economy. Transition from this aspect means a transition from a routine to an innovative economy and society, which Slovenia has not achieved yet. This is a reason why we claim that Slovenia is still in transition (e.g., Bekö & Jagrič, 2011).

Very little is known on how SFF in transition economies face the challenges of succession. Owners/managers of SFF, mostly founders, practically have no experience in managing the succession process, as there is no tradition in these economies. Institutional support in a form of consulting and training is lacking as well and SFF are seldom subject of political or only occasionally public discussion (Duh, 2008). Our research focuses on the transition of SFF to the next generation as a potential for innovation processes in SFF in a transition economy. We explore innovativeness of the next generation and its importance for innovativeness and long-term sustainable development of SFF due to the fact that competitivness and long-term success are crucially determined by continuous innovation of products, processes as well as by social innovation. Our study aims at investigating crucial factors affecting innovativeness of successors in SFF in a transition economy. Therefeore, the main research questions, which we address in our contribution, are: Which factors strengthen or weaken innovativeness of the next generation in SFF in a transition economy? Why and how transfer of experiential knowledge (tacit knowledge shared through common experiences), routine knowledge (tacit knowledge routinized and embedded in actions and practice) and social capital of founder affect innovativeness of successors? Why and how entrepreneurialism and academic knowledge on the field of entrepreneurship affect innovativeness of successors?

We conducted in-depth literature review and applied multiple-case study approach in the process of searching answers to our resarch questions. We conducted case studies of ten SFF. We limit our research on leadership succession which is found to be “one of the most challenging tasks in an organizational life” (Zahra & Sharma, 2004, p. 334). Our research addresses only inter-generational family succession, since research findings indicate that a majority of family enterprises’ leaders have been found to be desirous of retaining family control past their tenure (e.g., Le Breton-Miller, Miller, & Steier, 2004). Due to strong presence of SFF in many Central and Eastern European post-socialist countries, we believe that our research findings could be of importance for academics, professionals and owners/managers of SFF in these countries.

This contribution is divided into four sections. Following the introduction section, the theoretical background is discussed in the second section. In the third section, methodology and findings with propositions are presented. The concluding section highlights the most important findings, future research directions and implications for owners and/or managers of family businesses.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Transition in Slovenia

Slovenia lies at the crossroads of commercial routes from the Southwest to the Southeast of Europe, and from Western Europe to the Near East. With approximately a population of two million living in a vastly diverse territory of 20,000 square kilometers it is a relatively small country. It is young country since it became independent state after the collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1990. Slovenia has entered European Union (EU) in May 2004 as the most advanced of all transition economies in Central and Eastern Europe.

Since 1990 Slovenia has undergone a threefold transition: (1) transition from a socialist to a market economy, (2) transition from a regional to a national economy, and (3) transition from being a part of Yugoslavia to becoming an independent state and a member of the EU (Mrak, Rojec, & Silva-Jáuregui, 2004). The transition to the market economy from the former socialist economy with social and state ownership in Slovenia was closely associated with the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The legal bases for the development of private SMEs were the Law on Enterprises (1988) and the Law on Craft (1988). The first law opened opportunities for the development of the private entrepreneurial sector, and the second law reduced obstacles for the development of the craft sector, especially limitations on employment in craft enterprises. Even though Slovenia’s macro-economic environment was traditionally not very supportive to entrepreneurship (Ramadani & Dana, 2013), the number of SMEs increased dramatically since the 1990s. In the year 2010 there were 126.965 enterprises in Slovenia, of which 99.8 % were micro (enterprises with 0–9 employees), small (enterprises with 10–49 employees) and medium-sized (enterprises with 50–249 employees) enterprises. Only 0.2 % of all enterprises in Slovenia had more than 250 employees, however providing 30 % of the nation’s jobs. The same percentage of jobs (30 %) is provided by micro enterprises. The size structure of enterprises and the employment share in Slovenia is comparable to the one in EU-27, whereas there are big differences in value added per employee. Value added per employee in EU-27 is 47,080 € and 29,840 € in Slovenia indicating that Slovenian enterprises considerably lag behind EU-27 average value added per employees (Močnik, 2012). Recent economic crisis has reduced a number of employees in Slovenian enterprises. In the time period 2008–2010 a number of employees has been reduced for 16.6 % in large enterprises, and for 4.9 % in SMEs. Contrary, micro enterprises increase a number of employees (1.6 % growth rate) (Širec, 2012).

Several researches ascertain that Slovenia is not in transition anymore when looking from legal perspective (e.g., Bekö & Jagrič, 2011). However, when looking from economic-development perspective Slovenia can still be viewed as a transitional economy since a transition from a routine to an innovative economy and society has not been finished yet. In many cases economic reforms have been faster than the change in mindset and the ability of people to adapt thereby delaying a transition (e.g., Dana & Dana, 2003). Recent GEM (Global entrepreneurship monitor) research for Slovenia show that a gap still exist between the respect people exhibit towards entrepreneurship as a profession and their belief that entrepreneurship is a good career choice (Rebernik et al., 2014). In authors’ opinion not enough effort has been devoted in society for transforming the declared respect of individuals for entrepreneurship as a profession into their actual decision to pursue an entrepreneurial career. Besides necessary creation of normal business environment in Slovenia, the efforts should be made to raise people’s awareness that entrepreneurship can be a good career path which allows a good work-life balance.

2.2 Family Business Succession and Its Specifics in Slovenia

One of the major problems family businesses encounter is the transfer of ownership and management to the next family generation (e.g., Sharma, Chrisman, & Chua, 2003). Research findings indicate that only 30 % of family enterprises survive to the second generation because of unsolved or badly solved succession to the next family generation, and many enterprises fail soon after the second generation takes control (Morris, Williams, Allen, & Avila, 1997). The low survival rates could be explained by research findings showing that family enterprises have become more conservative and less innovative over time (e.g., Donckels & Fröhlich, 1991), and second generation family businesses often fail due to inaction and reluctance to seek out new business opportunities (Ward, 1997). Dyck, Mauws, Starke, and Mischke (2002) suggest that succession can represent a strategic opportunity in rapidly growing firms or firms in emerging and dynamic markets which are facing changing managerial needs.

We believe that the survival of family firms across generations depends on their ability to renew through innovation. The realization of effective succession, and firm’s innovation and competitiveness in the succeeding generation depends to great extent on the preparation of the competent leader and enhancement of his/her innovativeness. The exploration of family business’s succession as a process of strategic renewal by enhancing successor’s innovativeness is of special importance for transition economies among which we still encounter Slovenia (as explained in previous section). According to some research results there are between 40 and 52 % (Duh & Tominc, 2005) or even 60–80 % of SFF in Slovenia (e.g., Glas, Herle, Lovšin Kozina, & Vadnjal, 2006), contributing 30 % of the GDP (Vadnjal, 2006) and the majority of them being in the first family generation (Duh, 2008). Recently the subject of discussion has become the problem of transferring family firms to the next generation. Namely, SFF established in 1990s, are approaching the critical phase of transferring firms to the next generation. Owners/managers of SFF, mostly founders, practically have no experience in managing process of succession, as there is no tradition of succession in Slovenia and similar is true for other transition countries. Since Slovenia is one of the innovation followers with a below average performance, the enhancement of innovativeness of successors and their firms is of crucial importance for the future of Slovenia as innovative society.

2.3 Successors’ Innovativeness

Innovativeness refers to “a firm’s tendency to engage in and support new ideas, novelty, experimentation, and creative processes that may result in new products, services, or technological processes” (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996, p. 142). In family firms, innovativeness is regarded as a highly important dimension of entrepreneurial orientation for long-term performance, together with autonomy and pro-activeness (Nordqvist, Habbershon, & Melin, 2008). According to our belief entrepreneurs are not managers, but innovators, therefore succession should contribute to enhancement of the level of entrepreneurship, rather than efficiency. More than production and ability to produce at the lowest costs, it is important that successors have entrepreneurial education and enough knowledge for innovation ability. According to Steier (2001) innovation ability of firms is complemented by social capital, which is defined as a stock of resources and abilities in a network of relationships between firms and/or people and it encourages cooperative behavior, thereby facilitating the development of new forms of association and innovative organization.

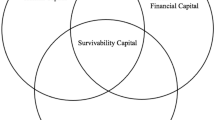

In our study we are exploring three constructs and that are entrepreneurialism (i.e., entrepreneurial competences of successors), knowledge transfer and creation, and social capital, and their impact on successors’ innovativeness.

2.3.1 Entrepreneurialism

Entrepreneurialism stands for entrepreneurial competencies, which are according to Ganzaroli, Fiscato, and Pilotti (2006): attitude toward problem solving, attitude toward entrepreneurship, social relationships, attitude toward risk, attitude toward negotiation, attitude toward team working, creativity, technical knowledge and competence, marketing knowledge and competence, administrative knowledge and competence, working commitment, communication skills, motivating skills. This definition coincides, although not entirely, with the description of factors, leading to innovation at the individual level as proposed by Litz and Kleysen (2001).

In our research we propose entrepreneurial competences as crucial for development of innovative capabilities of successors. We follow Ganzaroli et al. (2006) and their definition of factors, contributing to the formation of entrepreneurial competences: working experience outside the SFF, family context (i.e., familiness) and formal education (i.e., in entrepreneurship).

2.3.2 Knowledge Transfer and Creation

The processes of creating new and using existent knowledge are of crucial importance for fostering innovations in organizations. Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000) see organizations as entities which create knowledge continuously through so called SECI process (i.e., socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization), which is central to the organizational knowledge creation theory aiming at explaining organizational creativity, change and innovation.The concept of knowledge conversion is based on one of the most recognized typology of knowledge which differentiates between explicit and tacit (implicit) knowledge (e.g., Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009). In family business literature the transfer of tacit knowledge from predecessor to successor and successor’s training to assume the top management functions have been found to be key processes in developing and protecting knowledge and guaranteeing the continuity of the family business since family firms often “maintain their own ways of doing things—a special technology or commercial know-how that distinguish them from their competitors” (Cabrera-Suárez, De Saa-Pérez, & García-Almeida, 2001, p. 38). However, many authors suggest that successors have not only to acquire knowledge from the members of previous generation, but also add new knowledge and diverse perspectives (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Chirico, 2008; Kellermanns & Eddelston, 2004) since fast changing environment “requires raising potential successors who add future value to the firm by seeking new opportunities and fostering entrepreneurship” (García-Álvarez, López-Sintas, & Gonzalvo, 2002, p. 202). For this reason, different research studies address early exposure to a family business (e.g., Gersick, Davis, McCollom Hampton, & Lansberg, 1997), apprenticeship (Chirico, 2008; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004), the role of mentoring in family firms (Boyd, Upton, & Wircenski, 1999), involvement of the next-generation family members in decison-making and strategic planning (Mazzola, Marchision, & Astrachan, 2008) and team working, as well as knowledge accumulation by learning-by- doing (Chirico, 2008).

2.3.3 Social Capital

Social capital complements innovation ability of firms (Steier, 2001), and firms derive social capital from their embeddedness in the overall structure of a network and from their embeddedness in different relationships within a network (Uzzi, 1997). According to Light and Dana (2013) social capital that involves relationship of mutual trust and the norm of recipocity facilitate entrepreneurship only when supportive cultural capital exists. Social capital has also been explained as an internal phenomenon as “some aspect of social structure that facilitates certain actions of individuals within the structure” (Coleman, 1990, p. 302) and thus internal social capital. The complexity of social capital relates to many issues that can exist within the family firm, including “norms, values, cooperation, vision, purpose, and trust” (Pearson, Carr, & Shaw, 2008).

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) proposed three distinct dimensions of social capital: a structural dimension, a cognitive dimension and a relational dimension. According to Inkpen and Tsang (2005) structural dimension involves the pattern of relationships between network actors. It concerns the configuration of linkages among units or firms and the extent of centrality in social networks; a cognitive dimension reflects the shared purpose and meaning created through lasting relationships within the organization or group; and a relational dimension represents the trust, obligations, and commitments that result from the personal relationships that are created through the structural and cognitive dimensions.

3 Method

3.1 Case Study Approach

The research questions and the field development level on the topic researched induced us to adopt a qualitative empirical research approach. We used a multiple-case study approach (e.g., Yin, 2003), which has been widely accepted in family business research (e.g., Chirico, 2008). Multiple cases “permit replication logic where each case is viewed as an independent experiment that either confirms or does not the theoretical background and the new emerging insights” (Chirico, 2008, p. 435). Although there is no ideal number of cases, Eisenhardt (1989) believes that between four and ten cases is best in order to increase rigor. We selected ten cases from the database which authors of the paper have been creating for many years.

3.2 Data Collection

We selected ten cases of family firms in the size class of micro, small and medium sized family firms (from 0 to 249 employees). Namely, many micro enterprises face the problem of transferring ownership and management to the next generation. This is why we talk SFF. Limitation for the sample was that founder of the firm is employed in a firm, still owns a firm or is active in the firm, although retired, and that next generation is involved in a firm. For the purpose of our research we defined a family firm as the one in which a founder (i.e., an owner/manager) considers the business as a family one. Research was geographically limited to Slovenia.

The authors conducted personal interviews with a founder and a successor since they are very well qualified to elaborate on it and since there might be significant differences in perceptions between founders and successors (e.g., Zahra & Sharma, 2004). In all cases interviews took place at premises of a companyduring the working days. It is believed the timing and place of the interview did not influence on the readiness and openness to reveal data and information.

Our sample consists of ten SFF (two micro, four small, four medium-sized firms). They employ minimum eight workers (total of 657, average of 66), 39 family members. The geographical dispersion of the sample is favorable, as our selected cases cover all Slovenian regions. The average age of the SFF is 23.4 years. Most of SFF (five) report medium, two high and three low technological complexity of a firm. Eight successors are employed in their SFF. The average age of the successors is 29.7 years. The involved firms have 18 successors and 10 potential successors.

3.3 Data Analysis

We built ten extensive case studies and interviews of two respondents from each firm allowed us to compare the answers given by them. When analysing cases we were guided by a theoretical framework created from existing literature. Conceptual insights that emerged from cases helped us to refer to the existing literature to develope and enrich these insights. We conducted cross-case comparisons in order to refine emerging insights (e.g., Chirico, 2008). Interpretation and propositions were refined in several iterations before finalizing them. Data analysis was conducted applying a combination of deductive and inductive methods.

3.4 Findings with Development of Propositions

In this section we discuss findings and provide propositions for the future research arising from our case studies analysis. Our research is exploratory and thus seeks to stimulate further work focusing on innovativeness of the next generation and innovative performance of SFF in transitional economies.

3.4.1 Innovativeness of SFF and Their Successors

Our research revealed that although most founders report constant development of new products, services, processes, in order to remain competitive in their industry, only four have protected know–how, one of them has registered six and one eight patents on his name, two founders report over five registered patents on the name of the company. One founder has protected brand. Three successors are developing new processes and services with their parent. Successors all report constant development activities, seven report up to ten own developments of new solutions, especially in IT, improvements of existing services and processes, simplifications, which lead to cost reduction. They are less involved into development of new products. This is result of their non-technical formal education (only one successor has technical background). In the recent 5 years eight of the studied SFF have introduced over 530 new products, services and processes. Observed innovation activity of the SFF is dynamic, with successors taking more active role in development activities of SFF.

3.4.2 Entrepreneurialism

Working outside the family firm gives the successors “a more detached perspective over how to run and how to introduce changes and innovation in the business” (Chirico, 2008, p. 447) and usually occurs before the successor enters a family business for full time. Having previous working experience successor can integrate the knowledge transferred by the predecessor with the knowledge acquired during training process to assess and manage the firm’s familiness as well as to invest in replenishing, increasing and upgrading these knowledge bases as valuable resources (e.g., Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001). Findings of our research reveal that only two of the successors have previous working experience from the other firm in a different industry, and one has worked before in two other firms, in a different and same industry. All others report no previous working experience in other firms. Two successors also report internships in other firms in a different industry. Nowadays lack of working experience in other, but family firms, is strongly connected with economic situation and lack of job opportunities in Slovenia. According to seven successors’ communications skills, attitude toward negotiation and marketing knowledge and competence are the most affected by working experiences outside the SFF. Attitude toward problem solving is highly ranked but given less importance in comparison with the previously mentioned factors. The least importance is given to administrative knowledge and competences and attitude toward risk, while all other factors, from attitude toward entrepreneurship to motivation skills are evaluated as having moderate impact on development of entrepreneurial competences of successors. A right mix of out- and inside training experience is fundamental to acquire technical and managerial knowledge of the business and leadership abilities (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001). It plays a key role in creativity and innovation process (Litz & Kleysen, 2001).

The following proposition is derived upon above described findings:

Proposition 1

Previous working experiences outside a SFF are positively related to formation of entrepreneurial competences such as communication skills, attitude toward negotiation, marketing knowledge and competences, attitude toward problem solving and are negatively related with attitude toward risk; and consequently entrepreneurial competences are positively related to innovativeness of successors in SFF.

In family business research there is overwhelming support for the significant influence on successor’s performance played by educational level of successor (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Steier, 2001). Successor’s educational level should meet requirements needed to be an entrepreneur in a knowledge-based economy. It is no longer enough just to know how to perform a specific activity and/or function. Being competitive requires being able to create new knowledge. Successors in our study are all well educated: one of successors has a technical university degree, one in economics, others graduated or (three) still study entrepreneurship. In the eyes of successors, the most important significance is given to formal education’s impact on development of technical knowledge and competences, followed by marketing, administrative knowledge and competences and attitude toward team working. The least impact is given to working commitment and motivating skills. Formal education is basis for formation of human capital. In teaching the accent should be given to skills like critical thinking, creativity, communication, user orientation and team work, using domain specific and language knowledge. Entrepreneurship studies cover all these. The research has revealed that formal education in the eyes of successors affects development of creativity, but not to the same extent as e.g., technical or marketing knowledge and competences.

On the basis of above discussion we develope the following proposition:

Proposition 2

Formal education is positively contributing to formation of entrepreneurial competences such as technical and marketing and administrative knowledge and competences and is negatively related to attitude toward risk; entrepreneurial competences are positiviley related to innovativeness of successors in SFF.

The familiness can be understood as a mixture of cultural values, entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors. According to Cabrera-Suárez et al. (2001) there is great influence of a predecessor and a family on a successor in terms of cultural values, entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors. Familiness is according to different authors (e.g., Sirmon & Hitt, 2003) a resource that is unique to family firms. Habbershon, Williams, and MacMillan (2003) define familiness as the set of resources controlled by a firm resulting from a continuous overlap of a family system with the business system in a firm. Since familiness results from interactions among individuals, a family, and a firm over time (Chrisman, Chua, & Steier, 2003) which are the key variable of innovativeness of family firms, resulting in joint innovative results (Litz & Kleysen, 2001), it is an intangible, unique resource. As a distinctive bundle of intangible assets, Matz Carnes and Ireland (2013) believe that familiness has the potential to affect a family firm’s efforts to innovate. On the other side, familiness assumes a too strong involvement of founders into operative decision making and family issues, thus reducing their readiness for risk taking (Sethi, Smith, & Park, 2001). Our research revealed that in the eyes of successors (eight) familiness has a very strong impact on development of working commitment and attitude toward entrepreneurship (seven), followed by a strong impact on technical knowledge and competence (five), social relationships and attitude toward risk. Less but still important impact is assigned to motivating skills, marketing knowledge and competences, and attitude toward negotiation.

Most of successors (six) assign a very strong impact of entrepreneurial competences on their innovativeness, and agree (eight) that working experience outside the SFF and familiness has a strong impact on their innovativeness, while formal education has only moderate impact (seven) on their innovativeness.

From discussion above, the following proposition can be derived:

Proposition 3

Familiness relates positively to formation of most of entrepreneurial competencies and consequently most of entrepreneurial competences relate positively to innovativeness of the next generation in a SFF.

3.4.3 Knowledge Transfer and Creation

Firms need to transfer and acquire new knowledge as they seek to innovate and enhance performance (e.g., Nonaka et al., 2000; Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009). In SFF it is very important how and in which way predecessors transfer their tacit knowledge to successors thus enabling successor to get “hands-on” knowledge about the SFF and the industry. For this reason we explored different methods of tacit knowledge transfer (experiential and routine knowledge) from founders to successors of SFF. Many authors (e.g., Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Gersick et al., 1997) suggest that early exposure to a family business through summer and lower category jobs are valuable experiences for successors since they acquire in this way tacit knowledge, which is usually linked to a founder and therefore of particular importance during the transfer from the founding to the second generation (e.g., Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001). The successor can also absorb tacit knowledge about the business at home since “conveying the psychological legacy of the firm is an important part of child rearing from the beginning” (Gersick et al., 1997, p. 71). Especially, maintaining creative environments in families during childhood are prerequisite for creativity and innovation in businesses (e.g., Zenko & Mulej, 2011). The findings of our research show that most (seven) successors found early exposure and involvement into SFF as an important way of acquiring founder’s tacit knowledge. Most of them (nine) were exposed early, already as small children, to the family business environment.

Another important way of enhancing successor’s knowledge found in the literature (e.g. (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Chirico, 2008) is by mentoring and supervising relationships with family business leaders since they believe that the close interactions between them and their successor is a superior form of experience supporting development of tacit knowledge by successors. Mentoring is an effective way of transferring critical skills (i.e., technical and managerial), knowledge on managerial systems (especially of informal managerial systems), norms of behavior and firm’s values (Swap, Leonard, Shields, & Abrams, 2001). There is no common agreement on whether the parents are the most suitable mentors (e.g. Gersick et al., 1997), as well as diverse opinions on the role of formal in informal mentoring exist (e.g., Boyd et al., 1999). Our analysis revealed that all ten successors found mentoring as an important way of assimilating critical knowledge and skills (technical and managerial), mostly informal knowledge about management, norms of behavior, and SFF values. Nine successors were informally mentored by their parent, while seven were formally mentored by a non-family member.

Tacit knowledge can also be passed between family generations in the form of apprenticeship (Chirico, 2008), which is found to be an excellent training especially in traditional industries that do not operate in environments of rapid change. The findings of our research reveal that most (eight) of successors went through the apprenticeship in their SFF and four of them stressed that apprenticeship with observing, imitating and practising represents an excellent method of transferring founder’s tacit knowledge and their training.

In family businesses successors have the opportunity to learn directly from the preceding generation in a “learning-by-doing process” how to run the family firm, and “…, specially, all the ‘tricks of trade’ related to the business” (Chirico, 2008, p. 441). The findings showed that learning-by-doing, according to all ten successors’ high agreement, enables them indirect access to founder’s knowledge about managing the family business and business tricks. Seven of successors could learn about their family business directly from their parents.

Successor’s active participation in decision-making is found to be of crucial importance since both generations have the opportunity to offer suggestions for managing and improving processes and at the same time being able to learn from the other by transferring knowledge (e.g., Kellermanns & Eddelston, 2004). Mazzola et al. (2008) explored the role of strategic planning in the strategic decision-making process and revealed that the involvement of the next generation family members in the planning process, especially in the strategic planning, benefits their developmental process. This involvement enables the development of shared vision, provides the next generation with crucial tacit business knowledge and skills, deep industry and business knowledge, contributes to building credibility and legitimacy for the next generation as well as improves the relationships of successors with internal and external stakeholders. Namely, involvement of successor’s in meetings and communication with internal and external stakeholders (Mazzola et al., 2008) enables the assimiliation of the tacit knowledge of customers and suppliers and incorporation of that knowledge into new concepts, technologies, products or systems (Nonaka, von Krogh, & Voelpel, 2006). Case analysis revealed that most (seven) successors highly agree, while nine of them were also included, that involvement in the planning processes, especially strategic planning, enables them to assimilate critical tacit (business) knowledge and skills, insight into industry development, improves successor’s relationships within SFF and with partners out of the SFF thus contributing to their innovativeness. Nine successors have been involved into meetings even before they formally enetered the family firm.

Team work is found to be an important way of knowledge creation since “… through dialogue, their mental models and skills are probed, analyzed and converted into common terms and concepts” (Nonaka et al., 2006, p. 1185). Team knowledge is viewed as an important source of innovation since the combination of team member’s knowledge leads to new knowledge (Delgado-Verde, Martín-de Castro, & Navas-López, 2011). Team work, especially on the same project or as a part of processes of strategic planning and decision-making, is considered compulsory for the development of successor’s managerial carrier (e.g., Ganzaroli et al., 2006). Since it facilitates the creative interactions of both generations, is essential for a family firm to be creative and innovative entity (e.g., Litz & Kleysen, 2001). Family members’ specialized knowledge and its recombination enables the adaptation of the family firm to changes in environmental conditions (Chirico & Salvato, 2008). Majority of successors (eight) agree on the importance of the team work for knowledge transfer and creation of new knowledge as a source of innovations. Eight successors reported on working in teams as part of their training.

In the light of the above discussion the following propositions have been developed:

Proposition 4

Early exposure to a family firm, mentoring, apprenticeship, learning-by-doing, active successor’s participation in decision-making, (strategic) planning and team work are effective ways of knowledge transfer and creation, and are positively related to innovativeness of the next generation in SFF.

According to Szulanski (1996) there might be some obstacles that hinder knowledge transfer to the next generation in SFF, and that are: random ambiguity and unproven correctness, founder not interested to transfer knowledge, successor not motivated to accept knowledge, factors of circumstances, like limitations in organizations and bad relationship between predecessor and successor. Asking successors a question about the importance of founders’ interest for transferring knowledge to the successor, importance of successor’s motivation for accepting knowledge from the founder and importance of a good relationship between the founder and successor, we were not surprised, that all successors strongly agreed that these criteria are a pre-condition for successful transfer of knowledge. In all studied cases the pre-conditions for successful succession were at place which is confirmed by characteristics of the studied sample: regarding succession, in two SFF succession has been already fully done (management and ownership), in one case the founder is actively present in the firm while being retired, in the other case the founder is working for his SFF as a single entrepreneur. In two SFF management has been transfered to the successors, transfer of ownership is in procedure, both founders are retired, but active in the firms. In one SFF management is transferred, but not ownership, although founder is retired, but active. Three other SFF are in the midst of transfering ownership and management, one is in transfer of ownership only, the founder being still employed, but co-founder died, so transfer of ownership is more a process of regulating heritage. Only in two SFF there are only plans for succession and founders do not know or say when.

Proposition 5

Interest of the founder, successor’s motivation and good relationship between the predecessor and successor are positively related to successful knowledge transfer and consequently innovativeness of the next generation in SFF.

3.4.4 Social Capital

In our study we examined structural and relational dimension of internal social capital, while Burt’s (1992) perspective of social capital, primarily focusing on external linkages and what benefits arise from structural holes found within the network of relationships (Adler & Kwon, 2002), was omitted.

Structural dimension of internal social capital, which involves the pattern of relationships between network actors (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998), and can be studied through openness and quality of communication channels between the family members and between family and non-family members in SFF, is according to findings of our research very strongly present in SFF. The majority of successors (seven) highly agrees that honest communication between the family members as well as between family and non-family members in SFF is very important and contributes to creation of special and valuable ability to maintain long-term competitiveness and eases transfer of knowledge. As well they say that in their firms honest communication is taking place. Six successors say that it is very important not to have hidden agendas in front of other family members, and in their cases they omit such practice. Willingly sharing information with one another is being assessed as highly important by seven successors and flow of information does not represent an obstacle. The research shows the pattern of relationships which are based upon honest communication and information sharing between the family members, which enhances knowledge mobility and sharing between persons. This factor contributes to enhance innovation (Ganzaroli et al., 2006).

The relational dimension of internal social capital refers to the nature of the relationships themselves and the assets that are rooted in them (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). It manifests itself in strength of relations and trust. Strength reflects the closeness of a relationship between actors, and increases with frequency of communication and interaction (Hansen, 1999). Strong ties lead to greater knowledge transfer (Reagans & McEvily, 2003). Although some studies indicate that a high level of trust may also create collective blindness and inhibit the exchange and combination of knowledge (e.g., Lane, Salk, & Lyles, 2001), previous research has generally argued that trust increases organizational knowledge transfer. Trust enables the transfer of organizational knowledge since it increases partners’ willingness to commit to helping partners understand new external knowledge (Szulanski, Cappetta, & Jensen, 2004). The findings of our research reveal that all ten successors highly agree about importance of confidence in one another and a great deal of integrity with each other. Trust is strongly built into the relationships between the family members. All successors confirm that confidence strengthens the ties they have developed, increases open communication and knowledge sharing between the family members (e.g., Reagans & McEvily, 2003), thus contributing to their commitment to the SFF (e.g., Szulanski et al., 2004). We were not surprised by the finding that seven successors said that family members, meaning mostly founders, are not thoughtful regarding feelings of each other. According to Ganzaroli et al. (2006), founders have difficulties with succession, as decision for “stepping out of power” is not an easy one. There are many reasons, like fear for the future of the firm, for his/her own self-respect and identity, potential loss of respect—in family and in the community, and the lack of trust in successor’s skills, that help explain, why they might not be thoughtful regarding feelings of successors. They had to work hard for their success, they worked long hours, took responsibility and risk, so they expect from successors to show the highest level of commitment to the firm.

The above discussion leads us to the following proposition:

Proposition 6

Internal social capital facilitates transfer of knowledge through structural (i.e. number of relations and centrality) and relational capital (i.e. tie strength and trust) and its sharing between generations in SFF and consequently it is positively related to innovativeness of the next generation in SFF.

4 Conclusion with Limitations and Future Research Directions

In our study we investigated the factors influencing innovativeness of successors in SFF in transition economies on the case of Slovenia. We identified three constructs that help us to explain innovativeness of successors in SFF: entrepreneurial competences, knowledge transfer and creation, and social capital. Specifically we examined the impact of the following factors: previous working experience outside the SFF, formal education (in entrepreneurship) and familiness on development of entrepeneurial competences of the successor in SFF; different methods of knowledge transfer and creation: early exposure to the business, mentoring, apprenticeship, involvement in decision making, strategic planning, learning by doing, team working; structural and relational dimension of internal social capital and its impact on knowledge transfer and consequently on innovativeness of the successor in SFF. We developed a research model and introduced six propositions supported by data from ten cases thereby integrating them in the context of the succession and successor’s innovativeness in SFF in transition economies.

Propositions provide the basis for developing empirical testing, where the combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods should be applied in the future research. These propositions also have implications for practice as they provide useful cognitions for stakeholders involved in the succession process (i.e., especially family members) as well as professionals dealing with family businesses’ succession issues and innovativeness.

Our study provides a starting point for further, detailed research on family business and innovation management in SFF in transition economies, especially of factors enhancing/hindering innovativeness of founders, successors, SFF and innovative performance of SFF.

References

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Mangement Review, 27, 17–40.

Bekö, J., & Jagrič, T. (2011). Demand models for direct mail and periodicals delivery services: Results for a transition economy (Applied economics). London: Chapman and Hall.

Boyd, J., Upton, N., & Wircenski, M. (1999). Mentoring in family firms: A reflective analysis of senior executives’ perception. Family Business Review, 12(4), 299–309.

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saa-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–46.

Chirico, F. (2008). Knowledge accumulation in family firms: Evidence from four case studies. International Small Business Journal, 26(4), 433–462.

Chirico, F., & Salvato, C. (2008). Knowledge integration and dynamic organizational adaptation in family firms. Family Business Review, 21(2), 169–181.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Sharma, P. (2003). Current trends and future directions in family business management studies: Toward a theory of the family firm. Article written for the 2003 Coleman White Paper series.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Steier, L. P. (2003). An introduction to theories of family business. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 441–448.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dana, L. P., & Dana, T. (2003). Management and enterprise development in post-communist economies. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 1(1), 45–54.

Delgado-Verde, M., Martín-de Castro, G., & Navas-López, J. E. (2011). Organizational knowledge assets and innovation capability: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 12(1), 5–19.

Donckels, R., & Fröhlich, E. (1991). Sind Familienbetriebe wirklich anders? Europäische STRATOS-Erfahrungen. Internationales Gewerbearchiv, 4, 219–235.

Duh, M. (2008). Overview of family business relevant issues, Country fiche Slovenia. Institute for Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Maribor.

Duh, M., & Tominc, P. (2005). Pomen, značilnosti in prihodnost družinskih podjetij (Importance, characteristics and future of family enterprises). In M. Rebernik, P. Tominc, M. Duh, T. Krošlin, & G. Radonjič (Eds.), Slovenski podjetniški observatorij 2004, 2. del (Slovenian entrepreneurship observatory 2004, 2. part) (pp. 19–31). Institute for Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, Faculty of Economics and of Maribor.

Dyck, B., Mauws, M., Starke, F. A., & Mischke, G. A. (2002). Passing the baton. The importance of sequence, timing, technique and communication in executive succession. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 143–162.

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from the case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Ganzaroli, A., Fiscato, G., & Pilotti, L. (2006). Does business succession enhance firm’s innovation capacity? Results from an exploratory analysis in Italian SMEs. Working paper [n. 2006–29], 2nd Workshop on family firm management research, Nice, Italy. Available at: http://ideas.repec.org/p/mil/wpdepa/2006.29.html (Accessed 5 February 2014).

García-Álvarez, E., López-Sintas, J., & Gonzalvo, P. S. (2002). Socialization patterns of successors in first- to second-generation family businesses. Family Business Review, 15(3), 189–203.

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., McCollom Hampton, M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation. Life cycles of the family business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Glas, M., Herle, J., Lovšin Kozina, F., & Vadnjal, J. (2006). The state of family firm management in Slovenia. In Proceedings of 2nd workshop on family firm management research, EIASM, Nice, Italy.

Habbershon, T. G., Williams, M. L., & MacMillan, I. C. (2003). A united systems perspective of family firm performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 451–465.

Hansen, M. T. (1999). The search transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organizational subunits. Administration Science Quarterly, 44, 82–111.

Inkpen, A. C., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2005). Social capital, networks and knowledge transfer. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 146–165.

Kellermanns, F. W., & Eddelston, K. A. (2004). Feuding families: When conflict does a family firm good. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(3), 209–228.

Lane, P. J., Salk, J. E., & Lyles, A. (2001). IJV learning experience. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 1139–1161.

Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Steier, L. P. (2004). Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(3), 305–328.

Light, I., & Dana, L.-P. (2013). Bounaries of social capital in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 603–624.

Litz, R. A., & Kleysen, R. F. (2001). Your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions: Toward a theory of family firm innovation with help from the Brubeck family. Family Business Review, 14(4), 335–352.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

Mandl, I. (2008). Overview of family business relevant issues. Final report, Austrian Institute for SME Research, Vienna. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/entrepreneurship/craft/family_business/family_business_en.Htm (Accessed 31 July 2009).

Matz Carnes, C., & Ireland, D. (2013). Familiness and innovation: Resource bundling as the missing link. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1399–1419.

Mazzola, P., Marchision, G., & Astrachan, J. (2008). Strategic planning in family business: A powerful developmental tool for the next generation. Family Business Review, 21(3), 239–258.

Močnik, D. (2012). Temeljne značilnosti slovenskega podjetništva v primerjavi z evropskim (Basic characteristics of Slovenian entrepreneurship in comparison with the European). In K. Širec & M. Rebernik (Eds.), Razvojni potenciali slovenskega podjetništva: Slovenski podjetniški observatorij 2011/12 (Developmental potentials of Slovenian entrepreneurship: Slovenian entreprenurship observatory 2011/12) (pp. 15–28). Maribor: Faculty of Economics and Business.

Morris, M. H., Williams, R. O., Allen, J. A., & Avila, R. A. (1997). Correlates of success in family business transitions. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(5), 385–401.

Mrak, M., Rojec, M., & Silva-Jáuregui, C. (Eds.). (2004). Slovenia: From Yugoslavia to the European Union. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Koper: Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage Koper. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 5–34.

Nonaka, I., & von Krogh, G. (2009). Tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory. Organization Science, 20(3), 635–652.

Nonaka, I., von Krogh, G., & Voelpel, S. (2006). Organizational knowledge creating theory: Evolutionary paths and future advances. Organization Studies, 27(8), 1179–1208.

Nordqvist, M., Habbershon, T. G., & Melin, L. (2008). Transgenerational entrepreneurship: Exploring EO in family firms. In H. Landström, H. Crijns, & E. Laveren (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, sustainable growth and performance: Frontiers in European entrepreneurship research (pp. 93–116). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Pearson, A. W., Carr, J. C., & Shaw, J. C. (2008). Toward a theory of familiness: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(2), 949–969.

Ramadani, V., & Dana, L.-P. (2013). The state of entrepreneurship in the Balkans: Evidence from selected countries. In R. C. Schneider & V. Ramadani (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in the Balkans (pp. 217–250). Berlin: Springer.

Reagans, R., & McEvily, B. (2003). Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(2), 240–267.

Rebernik, M., Tominc, P., Crnogaj, K., Širec, K., Bradač Hojnik, B., & Rus, M. (2014). Spregledan podjetniški potencial mladih: GEM Slovenija 2013 (Overlooked entrepreneurial potential of young people: GEM Slovenia 2013). Maribor: University of Maribor, Faculty of Economics and Business Maribor.

Sethi, R., Smith, D. C., & Park, C. W. (2001). Cross-functional temas, creativity, and the innovativeness of new consumer products. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), 73–86.

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. H. (2003). Succession planning as planned behavior: Some empirical results. Family Business Review, 16(1), 1–14.

Širec, K. (2012). Razvojni potenciali slovenskega podjetništva (Developmental potentials of Slovenian entrepreneurship). In K. Širec & M. Rebernik (Eds.), Razvojni potenciali slovenskega podjetništva: Slovenski podjetniški observatorij 2011/12 (Developmental potentials of Slovenian entrepreneurship: Slovenian entrepreneurship observatory 2011/12) (pp. 7–13). Maribor: Faculty of Economics and Business.

Sirmon, D. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management and wealth creation in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 339–358.

Steier, L. (2001). Next generation entrepreneurs and succession: An exploratory study of modes and means of managing social capital. Family Business Review, 14(3), 259–276.

Swap, W., Leonard, D., Shields, M., & Abrams, L. (2001). Using mentoring and storytelling to transfer knowledge in the workplace. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 95–114.

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness. Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(Special Winter Issue), 27–43.

Szulanski, G., Cappetta, R., & Jensen, R. J. (2004). When and how trustworthiness matters: Knowledge transfer and the moderating affect of causal ambiguity. Organization Science, 15(5), 600–613.

Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464–476.

Uzzi, B. (1997). Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 35–67.

Vadnjal, J. (2006). Innovativeness and inter-generational entrepreneurship in family businesses. In Cooperation between the economic, academic and governmental spheres—Mechanisms and levers. Proceedings of the 26th conference on entrepreneurship and innovation, Maribor.

Ward, J. L. (1997). Growing the family business: Special challenges and best practice. Family Business Review, 10(3), 323–337.

Yin, K. R. (2003). Case study research, design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Zahra, S. A., & Sharma, P. (2004). Family business research: A strategic reflection. Family Business Review, 17(4), 331–346.

Zenko, Z., & Mulej, M. (2011). Diffusion of innovative behavior with social responsibility. Kybernetes, 40(9), 1258–1272.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Letonja, M., Duh, M. (2015). Successors’ Innovativeness as a Crucial Succession Challenge of Family Businesses in Transition Economies: The Case of Slovenia. In: Dana, LP., Ramadani, V. (eds) Family Businesses in Transition Economies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14209-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14209-8_8

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-14208-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-14209-8

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)