Abstract

This paper reviews the experience of financial integration in the euro area since the start of the EMU and focuses on the possible impact that the implementation of the Banking Union (in particular the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism) might have on the future process of financial integration. To that end, the paper first describes the main past developments in financial integration both at the euro area level and at a disaggregated level (e.g. in specific market segments) through a wide range of indicators. Second, it assesses the degree to which the integration process achieved the main benefits usually expected from financial integration (i.e. enhanced risk-sharing and improved capital allocation) while avoiding potential negative effects in terms of financial stability as well as it evaluates the experience of financial fragmentation during the crisis. Third, it provides some preliminary considerations on how the implementation of the Banking Union might affect some less positive elements of the past experience of financial integration if these tended to manifest themselves again in the future. Overall, the Banking Union is expected to have a positive impact by promoting a more balanced financial integration process and contributing to reducing the diffusion and negative effects of financial fragmentation in times of crisis. This enhanced quality of the financial integration process would be to a large extent the result of the Banking Union making the conduct of prudential supervision and bank resolution more effective.

Adviser to the Executive Board—European Central Bank (ECB). Views expressed in this paper do not reflect necessarily those of the institution. The author is grateful to Andreas Baumann, ECB, for his valuable research assistance.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

This paper reviews the experience of financial integration in the euro area since the start of the single currency and concentrates on the issue of how the financial integration process could develop in the future in particular as a consequence of the implementation of the Banking Union. The focus is in particular on the potential effects of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) which started on 4 November 2014 and of the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) which entered partially into force on 1 January 2015.Footnote 1 The possible role of a common financial backstop as an element of the Banking Union is also acknowledged where appropriate.

The issue addressed in the paper is relevant since the process of financial integration in the euro area—characterised by a significant increase in integration in the run-up to the crisis and a diffused fragmentation during the financial and sovereign crisis—has unfolded in forms which may have not fully realised the main benefits normally expected from financial integration and may have produced some negative side effects in terms of the public objectives of financial and monetary stability.

Therefore, it is timely at the current juncture—in which a slow process of recovery of financial integration in the euro area is taking place—to assess what kind of impact the Banking Union might have in case past financial integration developments tended to manifest themselves again in the future. In this respect, a general expectation is that the Banking Union might “generate a higher quality of financial integration” (Draghi 2014).

The paper is organised as follows. We first review the main benefits of financial integration as well as potential negative side effects. Secondly, we describe the main elements of the Banking Union and its main impact banking policies (supervision and resolution). Thirdly, the main past developments in financial integration at the euro area level are presented also in comparison with global trends. Fourthly, we analyse specific features of the financial integration and fragmentation processes at a disaggregated level (e.g. in main financial market segments) from the viewpoint of the main benefits (and possible negative side effects) of financial integration and provide a qualitative assessment of the potential impact of the Banking Union. We draw finally some conclusions.

2 Main Benefits of Financial Integration

While the relevant literature on financial integration highlights many benefits of financial integration, there is a widespread agreement that the two most important ones relate to risk-sharing and capital allocation.Footnote 2 While these benefits can refer to developments both within a country and across countries, the focus in this paper is on the cross-border dimension.

Financial integration between countries can promote enhanced risk-sharing in any of the countries concerned mainly through increased portfolio diversification across borders thus improving the countries’ absorbing capacity to withstand shocks. This capacity would vary depending on the financial market segment which is affected by the integration process. Integration in equity markets is supposed to have a stronger effect due to the fact that shocks are immediately fully absorbed by equity owners while debt securities holders absorb shocks only when the debt servicing capacity of the securities issuers is impaired (e.g. insolvency).

The aspect of risk-sharing is particularly important in the context of monetary unions, such as the euro area, since countries adopting a single currency have at their disposal less policy tools to adjust to macroeconomic asymmetric shocks. In particular, these countries give up their exchange rate and country-specific monetary policy tools. Therefore, for these countries the financial diversification brought by integration can be a form of external insurance against asymmetric shocks. Van Beers et al. (2014) analyse how the various external insurance mechanisms, including through financial and banking markets, have operated until recently in the euro area also in comparison with the US experience.

Financial integration between countries can also favour improved capital allocation in any of the countries concerned as a result of many factors including increased availability of funds, enhanced competition among financial institutions and diffusion of financial knowledge and expertise. To the extent that financial integration allows for wider investment opportunities in a country, this could translate also into better macroeconomic performance. This could be as well the result of financial integration allowing for access to finance to economic sectors previously excluded.

Financial integration may however have also some negative side effects in terms of financial stability. In particular, financial integration can take forms which sow the seeds for future financial instability. This could be the case for instance of financial integration in the form of cross-border financial flows mainly of short-term nature which are by their very nature very volatile and thus can create financial stability problems in the recipient countries.

The reverse of financial integration, namely fragmentation which may arise during a crisis, has always the negative connotation of reducing the benefits gained in the precedent integration period and may take forms which are detrimental to the smooth functioning of the monetary policy function as shown by the experience of the sovereign crisis in the euro area.

Against this background, a high quality process of financial integration is the one able to maximise the expected benefits while keeping the potential negative side effects in terms of financial stability to a minimum. At the same time, a not too negative process of financial fragmentation in a crisis situation can be the one with a limited impact on the benefits gained in the integration period and limited negative side effects on the effectiveness of monetary policy. These are the metrics under which we review past developments in financial integration. This can be only a broad qualitative assessment since it is very difficult to set quantitative benchmarks. Before we do that, we consider the main elements of the Banking Union.

3 Main Elements of the Banking Union

The Banking Union is composed of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM),Footnote 3 an extended harmonisation of national regimes for deposit insurance (Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive) and a common financial backstop in the form of the Bank Direct Recapitalisation (BDR) instrument of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The Banking Union represents an enormous institutional progress in comparison with the previous situation where responsibility for banking policies was exclusively at the national level. For the time being, it remains incomplete due to the lack of a Single Deposit Insurance Mechanism and the limited scope of the common financial backstop though for the latter there is a commitment of member states to develop in the future a common financial backstop also for bank resolution.Footnote 4

The adoption of the Banking Union responded primarily to a crisis management need, namely to reduce the negative feedback loop between sovereign and banking risks which spread during the sovereign crisis in the euro area. In general, this loop can manifest itself in two forms:

-

banking problems turning into fiscal problems due to the fact that government is the ultimate guarantor for its own banking system and under the circumstances of a weak fiscal position and a large size of the banking sector vis-à-vis the economy;

-

fiscal problems turning into banking problems since the costs of government funding are the basis for the costs of bank funding and domestic sovereign bonds represent a large share of bank assets.

The Banking Union is meant to address primarily the first dimension of the negative loop by basically reducing to a minimum the potential for government support to banks. To that end, the SSM is to be regarded as the first step intended to reduce the probability of banking problems mainly through an increase of effectiveness of prudential supervision of banks. This should be achieved through various channels including a reduction in the domestic bias in the supervisory action, a convergence of supervisory practices towards the highest quality and a substantive improvement of the supervision on a consolidated basis.

Despite this expected improvement brought by the SSM, there will be nevertheless banking problems. The main objective of prudential supervision is not zero failure but rather prudent risk behaviour of banks to reduce the risk of failure to a minimum. Therefore, an effective bank resolution mechanism is also needed to manage effectively bank failure so that the potential for government intervention is reduced. This goal is first pursued by the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) by introducing in all EU countries a common resolution toolkit (sale of business, bridge institution, asset separation and bail-in) and by setting up national resolution funds financed by the banking industry as well by imposing a prior use of private money to cover losses before public money could be used.Footnote 5

The objective is further pursued by the SRM which is meant to ensure a smooth resolution process for the significant banks under the direct supervision of the ECB and cross-border banks through a centralisation at the EU level of the decision-making process (Single Resolution Board, Commission, Council) and the setting-up of a Single Resolution Fund pooling the resources of the national funds. The SRM was necessary also to ensure overall consistency of the institutional framework for banking policies: maintenance of national responsibility for bank resolution in the presence of the SSM would create misalignments of incentives between resolution authorities and the single supervisor.

Therefore, to the extent that the SSM and the SRM (together with the BRRD) are effective in practice, the likelihood that a government has to support its ailing banks would be greatly reduced but not removed completely. To that end, it is necessary to have a common financial backstop which would mutualise the residual risk for governments thus de-linking fully a domestic banking sector from its own government. In that sense, it is only once the envisaged common financial backstop for bank resolution (fiscally neutral) has been agreed and implemented that the overall framework can be regarded as addressing fully the negative loop between sovereigns and banks.

4 Financial Integration at the Euro Area Level

Main developments in financial integration in the euro area can be seen through the lenses of a new indicator developed by the ECB, notably the Financial Integration Composite (FINTEC) indicator.Footnote 6 The FINTEC is an aggregation of selected price- and quantity-based indicators developed over time by the ECB to monitor financial integration in the main market segments of the euro area. Price dispersions and cross-border holdings are the basis for the calculation of price- and quantity-based FINTEC respectively,Footnote 7 while the monitoring process covers the money, (government and corporate) bond, equity and banking markets. The different time series (since 1995 and 1999 respectively) for the price- and the quantity-based FINTEC are due to the availability of the underlying data.

As shown in Fig. 1, the FINTEC indicates how the degree of financial integration in the euro area measured in terms both of prices and quantities varies overtime. By construction, the value of the FINTEC ranges between 0 (lack of integration) and 1 (full integration).Footnote 8 The price-based FINTEC indicates that the overall level of financial integration increased substantially between the introduction of the euro and the financial crisis, reflecting similar developments in the underlying market segments. At its peak, the level of integration was not far away from the defined level of full integration.Footnote 9 With the financial crisis and even more the sovereign crisis, there was a strong reversal in the process of financial integration (fragmentation) reaching a low level comparable to the one prevailing before the introduction of the euro. It is only with the announcement of the Banking Union and the ECB Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) operations that a process of recovery of financial integration started which is still under way.

Composite indicators of financial integration (FINTECs). Source ECB. Notes The price-based FINTEC aggregates ten indicators at the monthly frequency, covering the period Q1 1995–Q3 2014, and the quantity-based FINTEC aggregates five indicators at the quarterly frequency, covering the period Q1 1999–Q1 2014.

A similar pattern is shown by the quantity-based FINTEC though the level of integration measured through cross-border holdings tends to be lower than the one measured through price dispersions. At its peak, the quantity-based FINTEC was still far away from the defined level of full integration. In general, this bears the question of better understanding—in monitoring financial integration—the interplay between price and quantity dynamics beyond the obvious consideration that normally quantities tend to react more slowly and to a lesser degree than prices.

Developments in financial integration in the euro area should not be seen in isolation but rather against the background of the process of financial integration at the global level. Concerning equity and bond markets, Fig. 2 plots bilateral holdings of equity and debt securities within the euro area and among a selected sample of advanced economies (expressed as % of the respective GDP). This can be regarded as another quantity-based indicator to measure the degree of financial integration.

The figure shows that the patterns over time are similar in both geographical areas though not surprisingly the effects of the sovereign crisis were felt more in the euro area than at the global level. Interestingly the level of financial integration was normally higher in the euro area than globally reflecting the fact that a single currency provides further favourable conditions (such as disappearance of foreign exchange risk) for financial integration.

Concerning bank markets, Fig. 3 presents bilateral foreign bank claims for the euro area and two selected geographical samples of advanced economies and other countries (rest of the world) respectively (as % of the respective GDP). While also in these markets the level of integration in the euro area remained normally higher, the euro area has suffered the most from the financial and even more the sovereign crisis. At its bottom, the degree of banking integration in the euro area was not far away from the one among the advanced economies. This may be due to the process of reduction of cross-border activities of many euro area banks as part of a broader bank deleveraging process.

Finally, it is interesting to compare developments in financial integration within the euro area with the rest of the European Union (EU). We confine ourselves to the banking markets. Figure 4 shows the evolution of foreign bank claims between the EU non-EA countries (UK and Sweden only) and the euro area in both directions as well as within the two areas. The figure indicates that in the run-up to the crisis there was not only a strong increase in banking integration within the euro area (see Sect. 5.1) but also in cross-border banking flows between the euro area and the rest of the EU in both directions. By contrast, the crisis determined a strong reduction of banking flows particularly from the EU non-EA countries to the euro area to very low levels. This raises the question of whether and when they will increase again.

5 Financial Integration at Disaggregated Level and Possible Impact of the Banking Union

In this section, we look at financial integration patterns at a disaggregate level (e.g. main financial market segments) with a view to providing an assessment of the quality of the integration and fragmentation processes and developing some considerations on how the past developments, if they tended to repeat themselves, could be affected by the Banking Union. We do so by distinguishing between developments occurred: (i) before the crises, where the main issue is the extent to which the process of increasing financial integration achieved the expected benefits while avoiding negative side effects on financial stability, and (ii) during the crisis, where a main aspect is the degree to which financial fragmentation triggered negative side effects in terms of monetary stability. Finally, we also highlight some structural developments.

5.1 Developments Before the Crisis

Before the crisis, as seen in Sect. 4, financial integration increased significantly at the aggregated level reflecting growing integration in the main market segments. However, the way in which this process unfolded in some segments can be regarded as not always positive from the viewpoint of the main benefits of financial integration. Two main aspects can be mentioned in this respect.

A first aspect relates to the geographical composition of financial flows within the euro area. Figures 5 and 6 show changes occurred in financial flows (bank claims and debt securities) between four regions (financial centres, euro area core and peripheral countries and others countries (rest of the word)) in the period 1997–2007.Footnote 10 The figures indicate that in the period concerned there was an increase in financial flows relating both to bank claims and, to a lesser extent, to debt securities from core to peripheral countries. In addition, core countries increased substantially their bank intermediation role between financial centres and peripheral countries. Overall, the process of increasing integration in bond and banking markets within the euro area reflected to a large degree increasing financial flows between core and peripheral countries. This development was reversed during the crisis.

Foreign bank claims in different regions (in USD millions). Source BIS consolidated banking statistics. Notes Immediate borrower basis, domestically owned banks, reporting countries: core EA countries: AT, BE, DE, FI, FR, NL; peripheral EA countries: GR, IE, IT, PT, ES; financial centre countries: CA, CH, DK, JP, SE, UK, US; counterparty countries: the same as for reporting countries, except for core countries as LU was added

While this integration process is likely to have achieved the expected benefits in terms of risk-sharing, it was possibly less advantageous in terms of capital allocation: the large amount of financial flows to peripheral countries is likely not to have been employed fully in the most efficient way as highlighted for instance by the rapid growth in some countries of bank lending to the real estate sector. It also had some negative effects in terms of financial stability for both sets of countries: in peripheral countries the banking system became excessively exposed towards certain economic sectors (again real estate), while in core countries the banking system became excessively exposed towards the peripheral countries. On balance, it is doubtful that this kind of development represents a high quality form of financial integration.

Looking forward, this type of developments is less likely to re-occur. The argument relies on the assumption that the past evolution mainly represented the financial side of macroeconomic dynamics within the euro area. In particular, financial integration would have allowed the current account imbalances of peripheral countries to be financed by core countries which in turn would have acted also as intermediaries for investors outside the euro area (e.g. Chen et al. 2013). Against this background, first these macroeconomic imbalances might have been just a one-off event associated with the introduction of the euro. Second, even if they tended to re-emerge, they should be more promptly detected and addressed through the new Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure (MIP) agreed at the EU level.

In addition, if imbalances were to turn out specifically in the euro area banking sector, there would be policy tools, associated with the Banking Union, which should help reduce the risk of financial instability. In particular, the SSM is expected to enhance the degree of effectiveness of prudential supervision thus reducing the possibility for euro area banks of building excessive risk concentrations towards economic sectors and/or countries. In addition, the new EU macro-prudential framework—laid down in the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) IV and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR)—provides national authorities with specific policy tools to remediate imbalances in the banking sector. These national responsibilities are complemented in the euro area by new macro-prudential powers that the SSM Regulation assigns to the ECB so increasing the likelihood of an effective policy toolkit to address financial imbalances related to the banking system.

A second aspect relates to the main features of banking integration. Figure 7 shows the evolution of banks’ holdings of bank debt securities by country of issuer.

The figure shows that between the start of the euro and the financial crisis there was a substantial reduction of domestic debt securities and a corresponding increase in the holding of securities issued by banks in other euro area countries up to 40 % of respective total holdings. During the crisis the process went into reverse to stabilise more recently with the abatement of the sovereign crisis.

Turning to lending activity, Fig. 8 provides the share of cross-border loans for different typologies of loans, namely interbank loans, loans to non-financial corporates and loans to households. Before the crisis the share of cross-border interbank loans increased from 25 to 35 % of the total interbank lending. By contrast, cross-border lending to non-financial corporates increased slightly before the crisis (from 5 to 7.5 % of total lending to corporates) to remain then at that low level, while cross-border lending to households has always been insignificant.

Taken together, the two figures show that the process of increasing banking integration in the euro area took place primarily through cross-border interbank financing in the form either of purchase of bank debt securities or of interbank lending. By contrast, cross-border lending to the real economy remained a very limited share of the overall cross-border bank activity.

A process of banking integration mainly in the form of interbank financing is likely to bring the expected benefits of financial integration in terms of risk-sharing. As to capital allocation, the high share of interbank financing implies that the investment decisions in a given country fall exclusively on the domestic banking sector which may bring less efficient choices in case of very high amounts of available funds. This could be one of the reasons why some banks in the euro area became overly exposed to certain economic sectors. Whether a configuration with a higher share of direct cross-border lending to the real economy would be more efficient remains a matter for further analysis but it seems intuitive that, when capital allocation choices are shared between domestic and foreign banks, the outcome is likely to be more efficient. In addition, from the viewpoint of financial stability, cross-border interbank financing is subject to a higher degree of volatility than cross-border direct bank lending.

Overall, the process of banking integration in the run-up to the crisis had some drawbacks and it would be desirable to avoid them in the future process of financial integration. To that end, an increase in the share of direct cross-border lending to the real economy could help.

In this respect, while further analysis is needed to better understand the reasons why historically corporates and above all households resort to a very limited extent to cross-border bank financing, the Banking Union is likely to provide a positive contribution. In particular, the SSM is expected to support both the demand and the supply side of bank credit. On the demand side, the more effective supervision by the SSM would enhance the degree of confidence in the banking sector in the euro area thus possibly providing an incentive for corporates and households to resort to cross-border bank lending. On the supply side, the adoption by the SSM of a consistent approach to supervision within the euro area should remove existing hurdles to cross-border lending relating to the implementation of supervision at the national level. In addition, the SSM, being less affected by domestic bias, should not favour ring-fencing of capital and liquidity at banks within national borders. Furthermore, the SSM should promote a revamp in the cross-border consolidation of the banking system.

The SRM—together with the harmonised legal framework for bank resolution at the EU level (BRRD)—may also play a positive role. In fact effective and credible bank resolution regimes—by making bailout less likely—should exert a powerful control over the risk-taking attitude of banks. If shareholders and creditors of banks consider bank resolution (in particular the bail-in instrument) credible they will have strong incentives for monitoring effectively the risk behaviour of banks. Therefore, to the extent that the new EU bank resolution framework turns out to be effective in practice, it would assist the SSM in promoting more prudent bank behaviour thus increasing the overall level of trust in the banking system (Ignatowski and Korte 2014).

Finally, the level of confidence in the banking system could benefit also from the introduction of the envisaged common financial backstop for bank resolution.

5.2 Developments During the Crisis

During the financial and sovereign crisis, as seen in previous sections, there was a reversal in the process of financial integration with fragmentation spreading in most market (money, bond and banking) segments, while the equity markets were less affected. This process of fragmentation not only removed most of the benefits gained during the precedent period of integration but also took forms which had some negative effects in particular for the monetary policy function. In this respect, we mention three main aspects.

The first relates to integration of money markets. Figure 9 presents a new quantity-based indicator developed by the ECB to monitor integration in the euro area money market (offset coefficient).Footnote 11 The indicator measures the extent to which increases (decreases) in total liquidity autonomous factors in a country explain the inflows (outflows) from (to) other euro area countries. In other words, the coefficient measures the degree to which domestic shocks to liquidity are offset by liquidity flows across countries. The value of the indicator ranges between 0 (lack of integration) and −1 (theoretical full integration). The value of −0.66 was identified—through an econometric analysis—as the reference value for a high level of integration in the period concerned (January 2003–January 2014).

The figure shows that the coefficient has been around the reference value in the period preceding the crisis thus indicating a high level of integration. By contrast, during the crisis, the value of the coefficient moved into an area indicating impairment in the cross-border re-allocation of liquidity, namely a significant reduction in the degree of integration in the euro area money market. This reduction was particularly acute during the sovereign crisis and was eased only following the announcement of the ECB OMT operations. More recently the value has stabilised close to the reference value. The reduction of cross-border liquidity flows was to a large extent the consequence of a decrease in the level of confidence among banks also as reflection of the sovereign risk.

During the crisis the process of financial fragmentation affected significantly in a negative way the effectiveness of the single monetary policy. In particular, the monetary transmission mechanism was considerably impaired as—especially during the sovereign crisis—short-term interest rates became more sensitive to domestic liquidity conditions.

The Banking Union is likely to reduce the likelihood of this negative effect in future crises for the same reasons highlighted above. The SSM and the SRM, by making prudential supervision and bank resolution more effective and promoting more prudent risk behaviour of banks, as well as the future common financial backstop for bank resolution are all likely to promote and maintain a high level of confidence within the banking sector even during crises.

A second aspect relates to integration in bond markets. Figure 10 shows the evolution of banks’ holdings of debt securities (government and corporate bonds) by residence of issuer in the period September 1997–January 2014. Before the crisis banks increasingly substituted domestic bonds with bonds issued in other euro area countries (and partly from the rest of the EU) thus increasing integration in these markets, while during the crisis the process reverted to stabilise more recently. These developments were mainly driven by the holdings of government bonds which represent the largest share of banks’ debt securities holdings.

In addition, the increasing banks’ home bias for government bonds was primarily occurring in peripheral countries. Figure 11 shows the banks’ holdings of government bonds as percentage of their total assets in the euro area as well as in core and peripheral countries.

The figure indicates that during the crisis the share of banks’ holdings of domestic government bonds increased more in the peripheral countries reaching in April 2014 around 9 % of total banking assets versus around 2.5 % in core countries. While during the crisis the gap between the two remained lower than the one prevailing at the inception of the euro, it is an issue of concern from a financial stability viewpoint given that banks in peripheral countries may become excessively concentrated towards their own sovereign thus reinforcing the negative loop between them.

The increasing home bias in banks’ holdings of government bonds may be the result of several factors. Battistini et al. (2014) provide evidence that, during the sovereign crisis, while all euro area banks increased their exposures to the domestic sovereign to hedge against the re-denomination risk until the ECB OMT operations, some banks in peripheral countries have increased their home bias even further as a result of various factors including: possible “moral suasion” by the respective governments, “carry trade” motivations given also their low level of capitalisation and the EU regulatory treatment of sovereign debt (e.g. risk weighting for capital requirements and large exposures regime). More in general, increasing home bias in the holding of government bonds in times of crisis may reflect a broad risk aversion attitude.

The potential impact of the Banking Union on this kind of developments is expected to be on balance positive. First, the SSM, as already mentioned, will be less affected by domestic considerations in its own action (reduction of domestic bias) and will be very attentive to developments in the concentration of sovereign risk and “carry trades” activities of banks. In addition, the SSM can be expected to play an active role when discussions on the regulatory treatment of sovereign debt develop at the EU level. Furthermore, more broadly, the Banking Union as a whole is likely to contribute to reducing the negative effects of a generalised risk aversion in the banking sector. All this should eventually reduce the home bias for sovereign debt in times of stress.

A third aspect refers to integration in banking markets. Figure 12 shows the pattern of the spread between lending rates of small and large loans. Small loans are assumed to be representative of loans to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The spread is shown for the euro area as a whole and for distressed and non-distressed countries for the period Jan 2003–Mar 2014.Footnote 12 The figure shows that for the euro area as a whole the spread has been steadily decreasing before the crisis, while it has increased during the crisis. Therefore, SMEs used to pay during the crisis much higher bank lending costs than large corporates and this spread was larger in distressed countries (where it reached at the peak a value of around 200 bps).

Spread between small and large loans (small loans up to EUR 1 mn). Source ECB. Notes “distressed” countries are Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal and Slovenia. Small loans are loans of up to €1 million, while large loans are those above €1 million. Aggregation is based on new business volumes. *The euro area series is calculated as weighted average of country spreads

This geographical fragmentation of the banking markets in the euro area in terms of costs of bank lending clearly affected the effectiveness of the single monetary policy with policy rates reductions not reflected in bank lending rates.Footnote 13 This development was the consequence of both demand and supply side of bank credit. On the demand side the deterioration of macro-economic conditions in distressed countries had a bearing on the demand for credit by the real economy. On the supply side, the need for banks in distressed countries to repair their balance sheet after the crisis experience as well as the high costs of funding also due to the sovereign risk contributed to a reduction in the offer of bank credit.

The Banking Union could contribute to reducing the risk of this kind of fragmentation in the banking markets in future times of crisis mainly in case of supply side issues. In that respect, the SSM is expected to promote the development and maintenance of banks’ healthy financial conditions thus reducing the likelihood of balance sheet constraints as well as to induce banks (jointly with the macro-prudential authorities) to build adequate capital buffers in good times so that banks would be better able to withstand shocks in stress situations. By contrast, the SSM would be less relevant in case of financial fragmentation stemming mainly from demand side issues for which macroeconomic measures of governments and central bank interventions would be appropriate.

5.3 Developments Through the Cycle

Beyond cyclical developments, the experience of financial integration in the euro area also shows two important structural aspects. The first one was already highlighted in Sect. 5.1 above and relates to the persistent home bias in bank lending activity to the real economy. In that context, we have pointed to the possibility that a larger share of direct cross-border lending to corporates and households might bring benefits in terms of capital allocation efficiency.

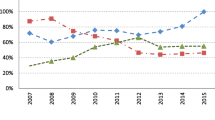

The second structural aspect relates to integration in equity markets. Figure 13 shows the ratio over time (2001–2012) between all equity and debt bilateral holdings within the euro area and the theoretical share of bilateral holdings assuming full integration.Footnote 14 As such, the indicator represents a way to compare the level of financial integration in the two markets.

Euro area bilateral equity and debt holdings (% of theoretical share of bilateral holdings). Sources IMF (CPIS), World Bank (WDI) and ECB calculations. Note The numerator is the sum of debt or equity bilateral portfolio holdings. The denominator is calculated as the sum of the products of the countries’ total portfolios multiplied by the share of the partner country in the euro area debt or equity market portfolio. The sample countries include Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain

In this respect, the figure highlights that the level of integration in equity markets has always been lower than in bonds markets though the gap has narrowed down during the crisis given the lower impact of the crisis on equity markets integration. Bearing in mind the potential benefits of financial integration, this structural element entails that there is still scope for reaping benefits in terms of risk-sharing/shock absorbing capacity within the euro area by increasing integration of the equity versus the bond markets.

To gauge the extent to which this would be possible, we can refer to an indicator of cross-border equity holdings. Figure 14 provides for the period 1997–2012 the share of equity issued in the euro area and held by residents in other euro area countries. The figure shows that throughout the whole period the ratio has steadily increased from 12 % in 1997 to 43 % in 2012 confirming once again that equity integration was marginally affected by the crisis.

Looking forward, the Banking Union is not the primary policy tool to achieve the objective of further equity market integration. This will require specific public actions including further legal harmonisation at the EU level in difficult fields such as corporate governance, insolvency and taxation.Footnote 15 These are likely to be main elements of the Capital Market Union project that the new Commission intends to pursue.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we have looked at the experience of financial integration in the euro area since the introduction of the single currency. First, we reviewed the main past developments at the aggregated and disaggregated levels. Overall the euro area experienced a first full cycle of financial integration with integration increasing significantly in all market segments in the run-up to the crisis and then decreasing during the financial and sovereign crisis with spreading fragmentation covering all market segments though to a lower degree in the equity markets. Only after the announcement of the Banking Union and the ECB OMT operations there were a stabilisation and the start of a re-integration process.

Second, we considered the extent to which the process of financial integration brought the two main expected benefits (i.e. enhanced risk-sharing and improved capital allocation) while containing potential negative side effects in terms of financial stability and the degree to which the process of financial fragmentation during the crisis had negative side effects.

In a nutshell, the result of this review is that the process of increasing financial integration seems to have brought to a large extent the expected benefit of risk-sharing, while the evidence is less conclusive in terms of improved capital allocation and it had some negative side effects in terms of financial stability. On the other side, the process of financial fragmentation during the crisis took forms which had substantial negative side effects on the monetary policy function. More specifically:

-

prior to the crisis, it is doubtful that two main features of the process of increasing financial integration—namely the geographical composition of financial flows (mainly from core to peripheral countries) and the predominant share of interbank financing in cross-border banking flows—were conducive to efficient capital allocation. In addition, the same features may have been an important driver behind certain developments—such as high volatility of financial flows, large concentration of bank exposures towards specific economic sectors and countries and asset price inflation—raising concerns from a financial stability viewpoint;

-

during the crisis, the process of financial fragmentation, in addition to withdrawing the main benefits gained in the previous period, was characterised—especially during the sovereign crisis—by a very high degree of home bias in money, bond and banking markets which impaired significantly the transmission mechanism of the single monetary policy.

Beyond the cyclical developments, two structural aspects have qualified the experience of financial integration throughout the period, namely a large degree of home bias in bank lending to the real economy (non-financial corporates and households) and a lower degree of financial integration in equity versus bond markets. The first aspect entails that a larger share of direct cross-border bank lending might bring positive effects in terms of capital allocation efficiency, while the second implies room for enhancing risk-sharing capability through higher equity market integration.

Third, we provided some preliminary qualitative considerations on the extent to which the implementation of the Banking Union, in particular the SSM and SRM (and where relevant the future common financial backstop for bank resolution), could affect the future process of financial integration if this tended to replicate past experiences. The Banking Union is expected to have a positive influence on those aspects of financial integration which are more closely affected by banking policies. In particular, the Banking Union—by pursuing the interrelated objectives of enhanced degree of effectiveness of prudential supervision and bank resolution, promotion of prudent risk behaviour of banks and maintenance of a high degree of public confidence in the banking system—is likely to contribute to:

-

reducing the likelihood of unbalanced patterns of financial flows between regions of the euro area (together with the EU Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure and the EU macro-prudential framework);

-

decreasing the share of cross-border interbank financing and increasing the share of cross-border direct bank lending to the real economy;

-

reducing the degree to which home bias would prevail in some market (e.g. money and bond) segments in periods of financial fragmentation.

Overall the Banking Union, to the extent it is effective in practice, should lead to a more balanced financial integration process in comparison with past experience by allowing in: (i) periods of increasing integration to reap fully the expected benefits while at the same possibly reducing potential negative side effects on financial stability and (ii) periods of crisis to reduce the intensity and impact of financial fragmentation.

By contrast, the Banking Union is less suitable to affect other developments such as cross-country differences in bank lending conditions when they reflect primarily demand side issues as well as a lower degree of integration of equity versus bond market. For the former government and central bank interventions are more appropriate, while for the latter the forthcoming project of Capital Market Union as part of the policy agenda of the new Commission is expected to play a key role.

Finally, it should be highlighted that the Banking Union, in addition to affect the possible recurrence of past developments, is also likely to trigger new dynamics in the process of financial integration which are difficult to foresee at the moment. In this respect, we mention just two possible developments. First, the SSM is likely to provide a strong momentum for banks in the euro area to carry out their capital and liquidity management on a group-wide basis and no longer along national borders thus providing further impetus to cross-border bank activities. Second, both the SSM and the SRM are likely to promote conditions for a revamp of banking flows between EU non-EA countries and the euro area in both directions.

Overall, it will be important to monitor very closely developments in financial integration in the euro area and the EU under the Banking Union.

Notes

- 1.

Some provisions of the SRM Regulation (e.g. on the Single Resolution Fund and bail-in mechanism) will enter into force on 1 January 2016.

- 2.

For a detailed review of main benefits of financial integration see Baele et al. (2004).

- 3.

Both the SSM and the SRM are complemented by and based upon the Single Banking Rulebook (Capital Requirements Directive IV, Capital Requirements Regulation, Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive) applying to the EU as a whole.

- 4.

In approving the compromise with the European Parliament on the SRM on 27 March 2014, the Council stated that during the transitional phase of the Single Resolution Fund a common backstop would be developed.

- 5.

The BRRD provides that losses incurred by a bank first need to be covered by using the bail-in mechanism for a minimum of 8 % of the bank’s total liabilities and second use can be made of the national resolution fund for a maximum of 5 % of the bank’s total liabilities (experience of past banking crises indicates that governments provide on average financial support to banks in the range of 13 % of total bank assets).

- 6.

The FINTEC was presented for the first time on the occasion of the publication of the ECB report on Financial Integration in Europe 2014 on 28 April 2014 and details will be presented in the ECB report “Finanical Integration in Europe”, April 2015.

- 7.

The calculation of the FINTEC entails three steps: (i) homogenisation of all indicators through a transformation on the basis of the “cumulative distribution function” (CDF); (ii) definition of a theoretical benchmark of full integration; and (iii) aggregation of sub-indices through either equal weights or size weights.

- 8.

For the price-based FINTEC the theoretical benchmark for full integration is assumed to correspond to a value of zero for all price dispersions, while for the quantity-based FINTEC the theoretical benchmark for full integration is determined on the basis of a “market portfolio” approach (i.e. each investor replicates the market portfolio).

- 9.

Given that price-based indicators of financial integration are based on price dispersions which reflect also risk premiums, they may over/underestimate the degree of financial integration depending on how correctly markets price risks. If—as it is commonly assumed—in the run-up to the crisis markets were under-pricing risks, price dispersion was lower and degree of financial integration higher than in case of correct risk pricing.

- 10.

Financial centres include Canada, Denmark, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, UK and US; core countries include Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Netherlands and Luxembourg; peripheral countries include Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

- 11.

The offset coefficient was introduced for the first time in the ECB report on Financial Integration in Europe 2014 (Special Feature A on “Geographical segmentation of the euro area money market: a liquidity flow approach”).

- 12.

“Distressed” countries include Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal and Slovenia.

- 13.

These aspects are analysed in more detail in the ECB Report on Financial Integration in Europe 2014 (Special Feature B on “Divergence in financing conditions of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the euro area”).

- 14.

Calculated on the basis of a “market portfolio” approach.

- 15.

These aspects are analysed in Sapir and Wolff (2013) and in more detail in the ECB Report on Financial Integration in Europe 2014 (Special Feature C on “Initiatives to promote capital market integration in the European corporate bond and equity markets”).

References

Baele, L., A. Ferrando, P. Hoerdahl, E. Krylova, and C. Monnet. 2004. Measuring financial integration in the euro area. ECB Occasional Paper No 14, Apr 2004.

Battistini, N., M. Pagano, and S. Simonelli. 2014. Systemic risk, sovereign yields and bank exposures in the euro crisis. Economic Policy 29: 203.

Chen, R., G.M. Milesi-Ferretti, and T. Tressel. 2013. Eurozone external imbalances. Economic Policy 28: 101.

Draghi, M. 2014. Financial integration and banking union. Speech at the conference for the 20th anniversary of the establishment of the European Monetary Institute, Feb 2014.

European Central Bank. 2014. Financial Integration in Europe 2014, Apr 2014.

Ignatowski, M., and J. Korte. 2014. Wishful thinking or effective threat? Tightening bank resolution regimes and bank risk-taking. ECB Working Paper No 1659, Apr 2014.

Sapir, A., and G. Wolff. 2013. The neglected side of banking union: reshaping Europe’s financial system, Breugel, Sep 2013.

Van Beers, N., M. Bijlsma, and G. Zwart. 2014. Cross-country insurance mechanisms in currency unions: an empirical assessment, Bruegel Working Paper No 4, Mar 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Grande, M. (2015). What Kind of Financial Integration Under Banking Union?. In: Paganetto, L. (eds) Achieving Dynamism in an Anaemic Europe. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14099-5_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14099-5_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-14098-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-14099-5

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)