Abstract

This chapter reconfirms the need for place marketing and place branding and reminds of the markets available to places. We point out the decision to place purchase, that is, to visit, invest or locate, is a high involvement one and guided by the Rossiter-Percy Grid, advertising messages must be believed as being true by recipients if there is to be a likelihood of purchase. Subject to the purchase motivation, the place benefits must either offer a solution to a problem or offer some form of enjoyment or even social approval. We argue that revealing and selecting a place identity should be at the base of place branding and marketing strategies. In doing so, a brand strategy is more representative of the characteristics of the place and will better align place advertising with other channels of place communication. In addition to being guided by relevant advertising and communication frameworks, we draw upon our research and relevant literature to support our arguments. The objective of our chapter is to contribute to the understanding of place identity and its role in effective place marketing and place branding strategies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Place marketing has come to the fore in recent years with an increase in academic work as well as practitioner interest and application. Notwithstanding earlier works relating to selling and promoting places, Kotler et al. (1993) reinforced the need for a marketing approach. They identified the markets for places as being new residents, corporate headquarters, tourists and conventioneers, investors and exporters. Reasons for a marketing approach include the existence of a supply–demand relationship between a place and its markets, the ability to segment these markets, the competition between places to appeal to these markets and also the increasing mobility or ‘brand switching’ by place purchasers. With regard to brands, a place name complies with earlier definitions as the name identifies and differentiates (American Marketing Association 2005). Marketing textbooks include the brand as part of the actual product when discussing the levels of product (core, actual and augmented). Notwithstanding, the meaning, importance and management of brands has advanced over the past decade, to the extent that an organisation can adopt a brand orientation which is an “inside-out, identity-driven approach that sees brands as a hub for an organisation and its strategy” (Urde et al. 2011, p. 15). In this regard, many of the concepts used in place marketing and place branding (e.g. brand, brand orientation, identity, image, attachment and loyalty) have prior use in other domains. Place researchers have used these concepts and related theories to guide research. In this work, we take a similar approach, with the aim of making a contribution to the relevance and application of place identity to place branding. To do this, we use the Rossiter-Percy Grid (Rossiter and Percy 1997) which was developed to guide advertising strategies. Some of our earlier research findings together with current literature are drawn upon to support our arguments. Central to our approach is the claim places are sellers seeking to attract and retain place customers who include tourists, investors and new residents. To effectively market and brand-manage a place, we point out that an understanding of what place consumers are buying, and as well, the type of buying-decision is essential. We argue it is place identity that is being offered by a place and can represent the value purchased by ‘place customers’.

Purchasing Places

As with other types of brands, place brands have the ability to communicate functional and symbolic meanings (Hankinson and Cowking 1995). Ideally, these meanings should relate to benefits, that is, the value offered. This value may provide a motivation to buy, pay a price premium, and be more loyal—all contributing to brand equity. With a focus on meaning, we commence our discussion by considering the role of advertising in the branding of places and in doing so, proceed to show the importance of place identity.

It should be remembered that advertising has the objective of motivating a consumer to trial or rebuy. Advertisements targeting place markets might encourage people to try the place (e.g. for a tourist—to visit; for and investor—to invest; for a new resident—to locate). Rebuy, depending on the nature of the market includes decisions to revisit, reinvest or remain. Related to the rebuy of places, loyalty is important. Place loyalty and related concepts place attachment and place satisfaction have been given attention by geographers (e.g. Brown and Raymond 2007), environmental psychologists (e.g. Hidalgo and Hernandez 2001) and place marketers (e.g. Zenker et al. 2013; Zenker and Rütter 2014).

To explain the place purchase decision (either trial or rebuy), we introduce the Rossiter-Percy Grid (Rossiter and Percy 1997), shown as Fig. 5.1.

Brand attitude strategy quadrants from Rossiter-Percy Grid. Source Percy and Rosenbaum-Elliot (2012)

The Grid is a 2 × 2 attitude framework, with the vertical axis being involvement, that is, ‘perceived decision risk’. The risk may be financial, functional, psychological or social and is dichotomised as being ‘high’ or ‘low’. The efforts individuals will make to reduce the likelihood of making a wrong decision can be used to indicate if a decision is high risk or low risk. The classification as to whether a decision is high or low risk for an individual is determined primarily through qualitative interviews (Rossiter et al. 2000). Referring to the Grid, and admittedly without the benefit of empirical data, we suggest the decision to purchase a place (visit, invest, locate) is a high involvement one as for most it involves financial, functional, and in some cases psychological and social risks. Conversely, low involvement decisions imply that the risk of making the wrong decision is minor; not an expected attitude when an individual is deciding to place purchase.

As shown in the horizontal axis of the Grid, Rossiter and Percy distinguish between negative and positive motivations, explaining the former are not ‘bad’ per se, but are negatively orientated with possible communication objectives being problem–solution, problem-avoidance or incomplete–satisfaction (Percy and Rosenbaum-Elliot 2012, p. 185). In contrast, positive motivations to buy are aligned to enjoyment and social approval. We contest that conspicuous consumption (Veblen [1899] 1931, p. 36), status consumption (O’Cass and McEwen 2004, p. 34) and cool consumption (Hebdige and Potter 2008) have relevance to positive motivations. Fashion is also relevant (Atik and Firat 2013) and has been contextualised to places (Lewis et al. 2013).

Regarding the purchase of place, two points are made. First and intuitively, potential purchasers must have an awareness of the place (the brand) and second have a positive attitude (not to be confused with positive motivation) towards the place for a purchase to be likely. The positive attitude must be based upon a benefit. We argue this benefit needs to exists within a place’s identity, and as we point out further on, should not be ‘made-up’, put into a slogan, tag-line and/or jingle and termed ‘the brand’. We draw on the high-involvement decisions in the Rossiter-Percy Grid to defend this stance.

As pointed out, the decision to purchase a place may be based on positive or negative motivations. For negative motivation, people who leave war affected or economically depressed places, for example, might be addressing a problem–solution motive. People who relocate to give their children a better education or more career opportunities would be an example of problem-avoidance motive, whereas people looking for a better lifestyle are addressing incomplete satisfaction. In contrast, people may decide to purchase a place for positive motivations, that is, to enjoy the place (sensory gratification) or to impress others (social approval). For further discussion on purchasing motivations, see Percy and Rosenbaum-Elliot (2012, p. 185).

While Percy and Rosenbaum-Elliot (2012) emphasise different communication strategies are necessary for negative motivations (being informational strategies) and positive motivations (being transformational strategies), in both cases, there are common requirements which we argue are relevant to places. If the place purchase decision is based on negative motivations, then information must be provided in a manner to convince the target audience. This includes understanding current attitudes. If people have a negative attitude, (not negative motivation) even if it is out-dated or wrong, they are not likely to buy. For this reason, place marketers need to know what attitudes are held by potential place purchasers and those who influence their decision. In one of our consultancies, we addressed this issue by interviewing external opinion leaders from industry sectors relevant to the place (Baxter et al. 2012). It is also necessary to establish what benefits are important to potential place purchasers.

If the place purchase decision is based on positive motivations, then aligned with the Rossiter-Percy Grid, not only must the message be accepted as true, the target audience must “personally identify with the brand and the benefits portrayed” (Percy and Rosenbaum-Elliot 2012, p. 193)—that is, the place will satisfy sensory gratification and/or social approval. Pivotal to our argument on place identity, potential purchasers in high involvement decisions must accept the benefits communicated as being true—an important point when considering the relevance of place identity to place marketing and place branding.

This section has established the type of decision involved in purchasing a place. Advertising of course is only one form of communication and we hold that other forms of communication should deliver a consistent message about a brand (place or other). For example, Ashworth (2009, p. 1) explains people “make sense of place by constructing their own understandings of them in their minds through contact points”. The contact points include: accumulated personal experiences; forms of representation such as films, novels and media reports; and deliberate policy interventions related to planning and urban design.

Communication

As mentioned at the outset, those involved in place marketing and place branding, have used established, yet relevant, concepts and theories to guide their research usually with the benefits and limitations of doing so being acknowledged. Studies in communications are a case in point.

Similarities exist between Kavaratzis’s (2004) city image communication model and Balmer and Gray’s (1999) model of the corporate identity-corporate communications process. Kavaratzis (2004) explains the content and result of place communications is image formation, whereas Balmer and Gray (1999) posit identity as the content of brand communications resulting in corporate images and reputation. We argue place identity is the content and result of place communications. As content, identity is communicated formally and informally. Kavaratzis’ (2004) model includes landscape, infrastructure, government structure, and internal stakeholder behaviours as contributing to primary communication. Similar to Balmer and Gray’s model, these characteristics refer to stakeholder’s first hand experiences with places (or organisations). Secondary or formal communications include public relations, visual identity systems and promotions and advertising; the latter being the focus of the Rossiter-Percy Grid discussed earlier. Finally, tertiary communication includes word-of-mouth (between internal-to-internal stakeholders and internal-to-external stakeholders), media and competitors’ communication. In the context of tourism Kerr et al. (2012) refer to the role and potential of ‘bragging rights’, a point which is likely to have relevance to other place markets. Bearing in mind that residents are producers of the place product, place identity is also the result of communication. As the primary, secondary and tertiary communications are interpreted by residents they inherently have influence on place product itself. We extend this point in the following section.

We now return to the point raised in the previous section about the requirement of brand benefits advertised (formal communication) being accepted as true by the potential purchaser in high involvement decisions (regardless of the motivation). In doing so, we also point out the futility of advertising a place message if it is not consistent with other forms of communication. A so-called brand tagline could be communicated by way of an advertisement but if the claim is not communicated through primary and tertiary sources, then it is unlikely this will be accepted as true by a potential place purchaser. Tertiary word of mouth communications by existing place purchasers to potential ones is a case in point. For this reason an identity-driven approach to place marketing and place branding is essential. We now explain place identity.

Place Identity

Place identity is a concept used in other disciplines including environmental psychology and geography. With regard to corporations, identity describes ‘who we are as an organisation’ (Brown et al. 2006, p. 102). Brown et al. (2006) explain the identity holders not only take part in the creation of organisational identity but are also shaped by it. The organisational member is a producer and consumer of organisational identity. We refer to the Structurational Model of Identification in which Scott et al. (1998) build upon Giddens' (1984) Structurational Model to support the duality of identity and identification. They explain identification both a process of attachment and a product of that process. Identification relates to emerging identities and has relevance to the identity-driven approach we subscribe to in place branding. Identity and the communication of that identity by individuals express belongingness, that is, attachment, to various collectives. Scott et al. (1998) remind of the social costs and rewards of maintaining various identities; a point we argue relates to the high involvement decision to place purchase which is in effect a process of identification. The place purchaser seeks a place which offers an alignment with their perceived or desired identity. The decision to visit, invest or relocate in a place by some individuals (or organisations) is an example of identification that contributes to an emerging identity. The impact of the Creative Class (Florida 2002) is an example of the identification process and a consequent emerging identity. Some of the characteristics of place identity are now provided.

Residents Are the Identity-Holders

Similar to the organisation and its employees, residents are the identity holders of a place. Residents have views about who (or what) we are as a place. As explained in more detail further on, ideally the identities held by residents need to be considered within place branding strategies. A place brand strategy that is far removed from its place identity (what we are) will not likely be accepted as true by residents let alone the external recipients of advertising communications.

Place Identity Is Pluralistic

The argument for multiple identities is established in the literature regarding individuals (Barker and Galasinski 2001), organisations (Balmer and Greyser 2003) and places (Baxter et al. 2013). With regard to nations, de Cillia et al. (1999, p. 200) conclude “there is no such thing as the one and only national identity”. Hall (2003, p. 194) explains these multiple identities occur from “positive and negative (place) evaluations”. The uniqueness and distinctiveness of a place is subjective to those who live there and is relative to their experiences. The place identities (identity-set) may include complimentary or uncomplimentary identities; not only towards each other, but even toward adopted marketing and brand strategies.

Place Identity Is Fluid

As a social and relational concept, place identities are inherently fluid and subject to change (Minca 2005; Mueller and Schade 2012). It is the socially derived expectations of a setting that influences cognitions, and hopefully reflects the intended value and significance of the setting to the individual (Stokols and Shumaker 1981; Wynveen et al. 2012). Altman and Low (1992, p. 7) describe places as “repositories and contexts within which interpersonal, community, and cultural relationships occur”. Although place identities are created through individual interpretations of place, they are constrained to the identity-holder’s cultural environment. We concur with Kalandides (2011) and Kavaraztis and Hatch (2013) in that the fluidity of place identities implies they are a process not merely an outcome of research. It is because place identities are fluid and influenced by sources within and outside the place, that constant monitoring and management of place identities is important.

Place Identity Is Co-produced

Co-production of place identity refers to the meaning-making process between residents and place, that is, residents are producers and consumers of identity. We subscribe that the multiples of place identity are the result of constant meaning-making processes between people and the place they live. Place identities are residents’ interpretation of place elements, such as culture, the natural and built environment and influenced by sources within and outside the place. Place as distinct from space requires human interaction. To illustrate, an outdoor basketball court in its simplest form is just a slab of concrete. As people utilise the space it becomes a place of sport and socialisation. Place identities are formed through communicative processes, between place and people, as well as between people.

Place identities are social and exist “in the experience, eye, mind, and intention of the beholder as much as in the physical appearance of the city or landscape” (Relph 1976, p. 5). From a city planner’s perspective of place, Hague (2005 , p. 7) describes environmental cognitions as the process of filtering “feelings, meanings, experiences, memories and actions” through social structures. In addition, Wynveen et al. (2012) propose the place meaning-making process is influenced by “the setting, the individual, and the individual’s social worlds” (Wynveen et al. 2012, p. 287). Therefore, the very essence of place is social. In their place branding model, Aitken and Campelo (2011) emphasise co-creation of meaning. Central to this model is the need to understand the shared identities within place. Understanding shared identities and how they represent daily life is crucial to creating an authentic place brand.

After reminding of the need for place marketing and place branding, we have addressed the nature of the place purchase decision, the types of communicative process for places followed by an explanation of place identity. We now proceed to expand upon the relationship between place identity and place brand management by drawing upon our own research work and relevant literature.

Place Identity and Place Brand Management

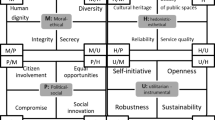

We have pointed out in an earlier work (Baxter et al. 2013) of the misunderstandings which exist between place identities and place brand identity. Place identity is pluralistic and fluid. Differently, place brand identity is selected and designed and more formally communicated. Figure 5.2 which relates to a study of the City of Wollongong, Australia (Baxter 2011) is used to explain this point.

Relationship between place identities, competitive place identity, and place brand identity. Source Adapted from Baxter et al. (2013)

Semi-structured interviews with a purposefully selected sample of Wollongong residents were used to reveal Wollongong’s identities. The objective was to reveal the ‘population of identities’ which are shown as ‘A’ in Fig. 5.2. The open arrow in ‘A’ is to suggest the fluidity of place identity. Not dissimilar to other places which have developed and implemented a brand strategy, Wollongong some 10 years prior to our study had selected and designed the tagline of ‘city of innovation’ as its competitive identity and brand identity. Interestingly, despite millions of dollars in promotion and a timeframe of a decade, the theme of innovation was not apparent in the revealed identities, raising some questions as to the appropriateness and effectiveness of the brand strategy. This brings us to the point as to the role of place branding in identity management. For instance, to argue the effectiveness of a place brand strategy, a longitudinal study of identities may show changes in identity over time and even emerging identities as discussed earlier; of course we acknowledge place identities are influenced by more than a brand strategy.

With the benefit of hindsight and the advantage of acquiring a better understanding of the nature of place identity and place branding, our recommendation is to select a competitive identity from the revealed identity set ‘A’ and link this with a designed brand identity. We point out that the designed identities (‘B’ and ‘C’ in Fig. 5.2) represent the strategic choices, in this case, led by the local council.

The discussion regarding Fig. 5.2 brings us back to the main argument in this chapter regarding the high involvement place purchase decision to visit, invest, or relocate. The Rossiter-Percy Grid insists advertising messages need to be accepted as being true in the minds of the place purchaser. We extend this argument to include other forms of place communication identified by Kavaratzis (2004) in particular word of mouth from current place purchasers. Referring once more to Fig. 5.2, the ‘city of innovation’ brand strategy and associated advertising campaign, we question how such communication would motivate the place purchase decision. Does it aid a problem–solution decision? Would it contribute to sensory gratification or social approval? Is the message accepted as being true?

From the findings of our research, as shown in Fig. 5.2, the identities of ‘potential’ ‘changing’ and ‘connected’ are examples of identities which could be selected as competitive identities and form the basis of a brand strategy. These identities could be benefits in an advertising message which have a likelihood of being accepted as being true by prospective place purchasers. Identities may communicate different benefits to different markets. For instance, ‘potential’ and’ changing’ may have appeal to investors and new residents but less so for tourists. This does raise the issue as to whether one selected and designed brand identity can be effective in multiple markets. Kerr and Balakrishnan (2011) refer to this issues in their discussion of place brand architecture. In addition to external relationships, a selected brand strategy may isolate and even alienate some internal stakeholder groups. Regardless of the place brand strategy deployed, the link to identities should not be overlooked.

Our approach to place branding is identity-driven. Supporting this Kavaratzis and Hatch (2013) refer to identity selection as producing a brand-identity statement, which should be negotiated between stakeholders through participatory methods. Using the terminology of Kavaratzis and Hatch's (2013) identity based place brand model, the objective here is to reflect and express place identities in communications.

Conclusion

Based on the need to market places, we argue that if the objective is to attract and retain desired place market segments, the place purchase decision needs to be understood. Central to our argument is the high involvement nature of the place purchase decision. What is advertised must be accepted as true—a difficult task if the message is not aligned in some way to place identity. Further and ideally, primary, secondary and tertiary communications should be aligned, remembering that residents in particular contribute to and deliver the brand promise. The place purchase decision is more likely to occur if the messages are consistent and accepted as true by potential purchasers. To achieve this, we subscribe to the view that an identity-driven approach is fundamental. Not only is a brand promise based on a complimentary identity likely to be believable, it has the potential to over-ride or even terminate some negative identities. We subscribe to the need for a better understanding of identity formation which in turn aids identity management through marketing and branding strategies. The development of new theory which will have both academic and practitioner relevance is our priority.

References

Aitken R, Campelo A (2011) The four Rs of place branding. J Mark Manage 27(9–10):913–933

Altman I, Low SM (eds) (1992) Place attachment. Plenum Press, New York

American Marketing Association (2005) Dictionary of marketing terms. http://www.marketingpower.com/mg-dictionary-view329.php?. Accessed 20 June 2007

Ashworth G (2009) The instruments of place branding: how is it done? Eur Spat Res Policy 16(1):22

Atik D, Firat AF (2013) Fashion creation and diffusion: the Institution of Marketing. J Mark Manage 29(7–8):836–860

Balmer J, Greyser S (2003) Revealing the corporation. Routledge, London

Balmer JMT, Gray ER (1999) Corporate identity and corporate communications: creating a competitive advantage. Corp Commun Int J 4(4):171–177. doi:10.1108/eum0000000007299

Barker C, Galasinski D (2001) Cultural studies and discourse analysis: a dialogue on language and identity. Sage Publications, London

Baxter J (2011) A systemic functional approach to place identity: a case study of the city of Wollongong. Masters by research masters by research thesis, University of Wollongong, Wollongong. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4371&context=theses

Baxter J, Kerr G, Clarke R (2013) Brand orientation and the voices from within. J Mark Manage 29(9–10):1079–1098. doi:10.1080/0267257x.2013.803145

Baxter J, Kerr G, Clarke RJ (2012) Identities and images of Wollongong. Wollongong City Council, Wollongong

Brown G, Raymond C (2007) The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: toward mapping place attachment. Appl Geogr 27(2):89–111

Brown T, Dacin P, Pratt M, Whetten D (2006) Identity, intended image, construed image, and reputation: an interdisciplinary framework and suggested terminology. Acad Mark Sci J 34(2):99

de Cillia R, Reisigl M, Wodak R (1999) The discursive construction of national identities. Discourse Soc 10(2):149–173

Florida R (2002) The rise of the creative class. Basic Books, New York

Giddens A (1984) The constitution of society. University of California Press, Berkeley

Hague C (2005) Planning and place identity. In: Hague C, Jenkins P (eds) Place identity, participation and planning. Routledge, Oxfordshire, pp 3–19

Hall S (2003) Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. Open University, Sage

Hankinson G, Cowking P (1995) What do you really mean by a brand? J Brand Manage 3(1):43–50

Hebdige D, Potter A (2008) A critical reframing of subcultural cool and consumption. Eur Adv Consum Res 8:527–528

Hidalgo MdC, Hernandez B (2001) Place attachment: conceptual and empirical questions. J Environ Psychol 21(3): 273–281

Kalandides A (2011) The problem with spatial identity: revisiting the “sense of place”. J Place Manage Dev 4(1):28–39

Kavaratzis M (2004) From city marketing to city branding: towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand 1(1):58–73

Kavaratzis M, Hatch MJ (2013) The dynamics of place brands an identity-based approach to place branding theory. J Marketing Theory 13(1):69–86

Kerr G, Balakrinshnan M (2011) Challenges in managing place brands. J Place Brand Public Dipl 8(1):6–16

Kerr G, Lewis C, Burgess L (2012) Bragging rights and destination marketing: a tourism bragging rights model. J Hosp Tour Manage 19(1):7–14. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/jht.2012.17

Kotler P, Haider D, Rein I (1993) Marketing places: attracting investment, industry, and tourism to cities, states, and nations. Free Press, New York

Lewis C, Kerr G, Burgess L (2013) A critical assessment of the role of fashion in influencing the travel decision and destination choice. Int J Tour Policy 5(1/2):4–18

Minca C (2005) Bellagio and beyond. In: Cartier C, Lew A (eds) Seductions of place: geographical perspectives on globalization and touristed landscapes. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 103–120

Mueller A, Schade M (2012) Symbols and place identity, a semiotic approach to internal place branding—case study Bremen (Germany). J Place Manage Dev 5(1):81–92

O’Cass A, McEwen H (2004) Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. J Consum Behav 4(1):25–39

Percy L, Rosenbaum-Elliot R (2012) Strategic advertising management, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Relph E (1976) Place and placelessness. Pion, London

Rossiter J, Donovan R, Jones S (2000) Applying the Rossiter-Percy model to social marketing communications. Paper presented at the ANZMAC 2000, Gold Coast, Australia

Rossiter J, Percy L (1997) Advertising communication and promotion management, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Scott C, Corman S, Cheney G (1998) Development of a structural model of identification in the organisation. Commun Theory 8(3):298–336

Stokols D, Shumaker SA (1981) People and places: a transactional view of settings. In: Harvey J (ed) Cognition, social behaviour and the environment. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, pp 441–488

Urde M, Baumgarth C, Merrilees B (2011) Brand orientation and market orientation—from alternatives to synergy. J Bus Res 66(1):13–20

Veblen T ([1899] 1931) The theory of the leisure class: an Economic Study of Institutions. The Viking Press, Inc., New York

Wynveen CJ, Kyle GT, Sutton SG (2012) Natural area visitors’ place meaning and place attachment ascribed to a marine setting. J Environ Psychol 32(4):287–296. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.05.001

Zenker S, Petersen S, Aholt A (2013) The citizen satisfaction index (CSI): evidence for a four basic factor model in a German sample. Cities 31(0):156–164. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.006

Zenker S, Rütter N (2014) Is satisfaction the key? The role of citizen satisfaction, place attachment and place brand attitude on positive citizenship behavior. Cities 38(0):11–17. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.12.009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kerr, G., Oliver, J. (2015). Rethinking Place Identities. In: Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., Ashworth, G. (eds) Rethinking Place Branding. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12424-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12424-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-12423-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-12424-7

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)