Abstract

In this Chapter, we analyse occupational segregation of Latin American men and women in conjunction with their residential segregation at national level as well as for the metropolitan provinces of Madrid and Barcelona. Given the small sample sizes of occupational data at sub-national level, we employ Iterative Proportional Fitting to adjust these to the national counts so that more reliable analysis of occupational segregation at sub-national level can be undertaken over the study period (2000–2010). We find that while residential segregation tends to decrease over time for both men and women, occupational segregation has increased during the same period, particularly among women. The results also highlight a negative correlation between occupational and residential segregation for both men and women, thus suggesting the existence of a multidimensional problem which demands specific target policies, particularly in the labour market realm.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

It is generally argued that patterns of employment for immigrants vary according to local labour market conditions (Waldinger 1996; Wright and Ellis 1997) which, in turn, depend on the geographies of residence of immigrant groups (Wright et al. 2010). It can be said, as Glasmeier and Farrigan (2007, p. 221) note, that “the end result is a city made up of labour markets and residential enclaves”. However, while most studies of residential segregation traditionally seek to identify the factors that determine spatial patterns of immigrants (Massey 1985; Clark 1992; Wilson and Hammer 2001; Zubrinsky Charles 2001), the study of occupational segregation in conjunction with residential segregation is generally marginalised in some geographical contexts such as Spain. This is, of course, surprising given that in an often cited and reprinted article by Duncan and Duncan (1955a) the degree to which members of different occupational categories are residentially segregated from each other is considered an important aspect with potential implications for policy. As Ovadia (2003, p. 314) notes, “determining whether these two forms of segregation are associated is not only an issue of understanding whether there is an empirical relationship between them. If effective policies for reducing racial inequality are to be developed, then understanding the structural form of its components is necessary”.

Therefore, if residential concentration and the institutionalisation of the provision of resources, goods, and services through social networks facilitates ethnic niching in metropolitan labour markets (Wilson 2003,), why do most studies in Spain fail to infuse the intra-urban residential geography into an understanding of the immigrant division of labour? One explanation may be that there is no correlation between the two forms of segregation and, therefore, residential and occupational disadvantage in metropolitan areas is multidimensional. However, to the best of our knowledge an examination of whether or not these two forms of segregation are associated has not been undertaken to date. One can speculate that this lack of research is largely due to difficulties in analysing occupational segregation by nativity and gender at sub-national scales, as local labour market data with such detail is unavailable and regional tables are subject to small sample sizes.

The purpose of this chapter is twofold. First, it provides an illustrative example of how to derive larger sample sizes of populations by country of birth and gender for the provinces of Madrid and Barcelona using both provincial and national data from the Spanish Labour Force Survey (LFS). Second, we employ such estimates to quantify the level and direction of occupational segregation for Latin American men and women in the metropolitan provinces of Madrid and Barcelona. In doing so, we also aim to shed further light on the possible correlates (positive, negative, no correlation) between occupational and residential segregation. In addressing these issues, we focus on three specific questions:

-

1.

Over the past decade, how do levels of occupational segregation for Latin American differ by gender?

-

2.

To what extent are there differences nationally and between the metropolitan provinces of Madrid and Barcelona?

-

3.

What is the correlation (positive, negative or none) between occupational and residential segregation and, if so, is this consistent between metropolitan areas and gender?

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows: the next section gives an overview of the links between immigrant employment and residence; the following section discusses the evidence from the Spanish context; next the data and methods we use are outlined; two sections then present results and a final section briefly summarizes our leading findings and discussion.

Are There Links between Immigrant Employment and Residence?

New immigrants tend to locate where they have social networks through an ‘invasion’ and ‘succession’ process so that the urban location of employment opportunities is constantly resurfaced, thus contributing to the creation of ethnic enclaves and niches in the original areas of settlement (Wilson and Portes 1980; Portes and Bach 1985; Portes and Shafer 2007). Kaplan (1998) suggests four ways through which residential concentration supports ethnic enclaves/businesses: (1) proximity to a market of ethnic consumers; (2) the opportunity for exchange of information and economic resources; (3) agglomeration economies; and (4) the ability to maintain cultural cohesion for the community. Of course, this is consistent with the notion that networks play a crucial role in immigrant settlements (Light and Bonacich 1988; Waldinger 1996; Light and Gold 2000), particularly in a context of dual labour markets (Piore 1979): with the primary sector providing good jobs and earning trajectories (mostly for natives) but the secondary market providing peripheral employment, including low prestige, low income, job dissatisfaction, and the absence of return to past human capital investments (Wilson and Portes 1980, p 301). Thus, although immigrant networks might facilitate the entry of immigrants into the labour market upon arrival, they may also constrain occupational opportunities and labour mobility (Portes and Sensenbrenner 1993). If the latter occurs people and families are generally less able to improve residential circumstances and such social immobility does not allow intra-metropolitan movement from immigrants into better areas (Massey et al. 1991). Light (1998) notes, however, that the agglomeration economy in ethnic/immigrant enclaves can also trigger the forces of dispersion when immigrant businesses consider reaching out to a larger and broader clientele. There are also other factors that might lead to immigrant dispersal such as intermarriage or “partnering out” (i.e. partner someone who is not a co-national) which is closely related to the improvement of immigrants’ access to labour market institutions (Ellis et al. 2006). For instance Holloway et al. (2005) and Ellis et al. (2012) showed that US mixed-raced households tend to reside in less-segregated areas than single-race households.

In the sociological literature, it is widely acknowledged that residential segregation in metropolitan areas serves as a system of inequality that contributes to unequal access to resources and systematically disadvantages lower-status groups (Massey and Denton 1993). Since immigrants are usually not economically well-off upon their arrival they cannot afford expensive transportation costs and, therefore, tend to live nearby their workplaces in a fairly concentrated and segregation fashion (Massey 1985). This process is clearly rooted in the spatial differentiation of the urban economy, and is reinforced by metropolitan areas which are already segregated to different degrees along the lines of class and gender and the local interplay of supply and demand (Peck 1996; Peck and Theodore 2001). Therefore, it is expected that “residential segregation may thus lead to employment segregation through a group’s spatial accessibility to specific clusters of industries and/or by its social accessibility to niche jobs through group networks” (Ellis et al. 2004, p 623).

Therefore the way an immigrant group is spatially incorporated into society is as important to its socioeconomic well-being as the manner in which it is incorporated into the labour force. In other words, if avenues of spatial assimilation are not blocked by prejudice and discrimination, most minority groups or immigrants are able to convert socioeconomic achievements into improved residential circumstances and such social mobility allows them to move into better areas and better jobs (Massey 1985; Massey and Denton 1988; Massey et al. 1991). As a consequence, it is important that levels and trends in residential segregation be documented in conjunction with labour market disadvantage, allowing the analysis of these variables to be fully incorporated into research about the causes of urban poverty.

So far the international evidence on the relationship between residential and occupational segregation has produced mixed results. While there seems to be greater support traditionally for the existence of a positive association between high levels of residential segregation and occupational disadvantage (Duncan and Duncan 1955a; Duncan and Lieberson 1959; Massey and Denton 1988, 1993), further research has led to inconclusive results. On the one hand, recent sets of evidence (Logan et al. 2002; Parks 2004; Wang 2006) reveal a similar positive association between residential and occupational segregation which is generally stronger for women than men. Although some other studies agree on the direction of the relationship, they differ in signalling that immigrant women are less concentrated than men (Wright and Ellis 2000). On the other hand, some scholars have found a negative association between occupational and residential segregation (Galster and Keeney 1988), and with results that suggest that the spatial patterns of occupational segregation do not vary greatly by gender (Ovadia 2003).

It becomes clear that although there seems to be ample support that increases in residential segregation are generally positively associated with occupational segregation, there is also evidence that groups “work together and live apart” (Ellis et al. 2004, p 634). Thus, the geographies of home and work may be actively shaping actual employment outcomes. However, when they are not positively correlated “we may tentatively conclude that social networks, regardless of their spatiality, trump geographical access and proximity in getting jobs” (Wright et al. 2010, p 1055). In this regard, the importance of spatial versus social accessibility in connecting residential and occupational segregation is largely to be subjected to the strength of a group’s social network. While social networks are central to understanding the maintenance of immigrant niches (Light and Bonacich 1988; Waldinger 1996; Light and Gold 2000), it has also been suggested that this element has been affected by the dispersion of jobs across metropolitan areas, which means that workers are more likely to commute beyond the boundaries of their community for employment than before. This “spatial disjuncture between home and work” is seen as a “distinct departure from the intra-metropolitan circulation patterns of earlier generations of migrants” (Zelinsky and Lee 1998, p 288). Gober (2000) believes that the adoption of this new sociospatial behaviour by some immigrant groups gives rise to deterritorised communities, whose glue is more in ethnic churches, social and service clubs, cultural centers and festivals rather than in traditional residential concentrations. Nonetheless, current research also emphasises the importance of characterising immigrant concentrations in order to understand labour market entry as well as employment niching (Ellis et al. 2007; Wright et al. 2010).

Evidence from the Spanish Context

Our chapter builds on two sets of empirical evidence from the Spanish context. First, in the labour market realm, it is widely acknowledged that the existence of regular and irregular avenues of international migration (Cachón 2002; Izquierdo and Martínez 2003; Aja and Arango 2006; Arango and Finotelli 2009; Sabater and Domingo 2012) and a preferential treatment for Latin Americans (Izquierdo et al. 2003; Peixoto 2009; Hierro 2013) acted during the years of the migration boom as a catalyst for the strong demand for labour-intensive and low-skilled jobs in low-paid occupational sectors. It is worthy of note that the latter is partly explained by the increased labour market participation by native women which resulted in an increased demand for female labour in the domestic service for cleaning, childcare and care of the elderly in Spain (Domingo and Gil-Alonso 2007; Vidal-Coso and Miret 2014; Simón et al. 2014), a situation not so different internationally (Lutz 2008).

As a consequence many migrant workers in Spain, including those from Latin America, largely represent a secondary market of workers (Cachón 2002, 2009) with low levels of skills, worse working conditions, and greater job instability. However, as the impact of the crisis in Spain has deepened, there has been a shift from a policy whose main objective was to recruit workers to meet the demands of the labour market to a policy which aims to improve the “employability” of unemployed resident immigrants (López-Sala 2013).

Second, it is generally recognised that the circumstances of arrival, skills, language, education, class, nativity and gender interact to create a heterogeneity of immigrant employment experience, with expectations that poor labour market outcomes for recent migrants are transitory and improve as immigrants acquire country-specific human and social capital (Schrover et al. 2007). Here, the imperfect transferability of human capital and time of residence appear as the central explanatory factors of migrant disadvantage (Chiswick 1978; Friedberg 2000). Following this classic explanation, it has been documented that immigrants experience a U-shaped pattern during their transition from the labour market in the country of origin to the labour market in the country of destination (Chiswick 1978; Chiswick et al. 2005; Akresh 2006, 2008). However, this has been less evident for immigrants in Spain (Amuedo-Dorantes and De la Rica 2007; Fernández and Ortega 2008; Izquierdo et al. 2009; Bernardi et al. 2011; Vidal-Coso and Miret 2014; Vidal-Coso and Vono-de-Vilhena, this book), thus posing the question of whether or not today’s immigrants will actually be able to “catch up” with the native population. Although there seems to be an upward labour mobility for those with pre-settled partners, especially among women (González-Ferrer 2011; Vono-de-Vilhena and Vidal-Coso 2012), immigrants remain to do worse than natives in the labour market even after controlling for similar sociodemographic characteristics (Cebolla and González-Ferrer 2008; Vidal-Coso and Miret 2014), particularly women. Therefore, although some studies reveal that upward mobility among immigrants occurs within the first 5 years of residence, the occupational status never seems to converge with that of natives with comparable skills (Alcobendas and Rodríguez-Planas 2009), a situation that is also observed for the immigrant-native wage gap (Izquierdo et al. 2009).

Third, it has become increasingly clear that the fact that immigrants are not equally distributed across the occupational structure in Spain is also due to a process of polarisation of employment in Spain (Bernardi and Garrido 2008; Stanek and Veira 2012). Generally, people are being employed in either professional and technical occupations or unskilled service work (Vidal-Coso and Miret 2014) and according to Amuedo-Dorantes and de la Rica (2007), such polarisation has made the labour complementarity process between the native and the immigrant population more prominent, and is particularly evident among female migrants. For instance, a study by Vidal-Coso and Miret (2013) revealed that the increased labour market participation by native women in recent years, which led to the externalisation of domestic tasks and increased demand for domestic and other personal services, resulted in a significant increase of women employed in domestic services and cleaning (64 %), most of whom (81 %) are immigrants. The latter aspect is intrinsically related to the growing representation of migrating women at international level (Massey et al. 2006; Donato 2006; Donato et al. 2011), which is considered the main factor in the feminization of migration flows in Southern Europe as a result of the growing global demand of labour power in the domestic work sector (Anthias and Lazaridis 2000; King et al. 2000).

In the residential realm, although location patterns of immigrants typically follow the spatial-assimilation model in Spain, the twin processes of immigration settlement and spatial integration have combined to produce a diversity of segregation patterns across groups. There are, however, two opposite poles. On the one hand, there is evidence of immigrant enclaves which are clearly associated to the enclave-economy hypothesis (e.g. for Catalonia and Barcelona see Solé and Parella 2005; and Serra 2012; for Andalucia, see Arjona 2007; for Madrid, see Riesco 2008; for specific nationalities, see Beltrán et al. 2006). On the other hand, there is also evidence of growing heterolocal residential behaviour (Sabater et al. 2012) which brings to view a co-existence of different sociospatial behaviours, with Latin American groups being closest perhaps to dispersal immediately after arrival (i.e. heterolocalism) and Asian groups displaying more economic integration but spatial encapsulation. In the middle is also a body of work which highlights the overall importance of the assimilation model, with the clustering of some ethnic groups reflecting the first stages of its process of concentration followed by dispersal. In this regard, studies have focused on immigrant clustering-dispersal in the main metropolitan areas of Madrid and Barcelona (Bayona 2007; Echazarra 2010; Martori and Apparicio 2011; Bayona and Gil-Alonso 2012; Sabater et al. 2012; Galeano et al. 2014; Sabater and Massey, this book). In general, although residential integration have occurred relatively quickly and decreasing residential segregation has been a characteristic of Spanish cities, there has been a renewed interest in research which tries to understand in greater depth the causes and meaning of residential clustering and dispersal for different groups. Whilst the spatial assimilation theory continues to provide a pivotal frame for the analysis of immigrant settlement, further understanding of the spatial behavior of recent immigrants is needed as demonstrated by the formation of enclaves and the existence of heterolocalism. Given the shortcomings of the traditional assimilationist theory, the latter is particularly relevant in a context of ‘a much greater range of location options in terms of residence and also economic and social activity than anything known in the past’ (Zelinksy and Lee 1998, p 285).

Therefore, although research to date suggests an ongoing process of spatial deconcentration is occurring among immigrants, much further understanding is needed to disentangle the main causes and/or mechanisms behind such residential behaviour. For instance, in this paper we argue that the fast dispersal immediately after arrival and the maintenance of the community without spatial agglomeration constitutes a remarkable feature among Latin American groups in Spain. However, this may be happening at the expense of occupational segregation, particularly among women.

Data and Measures

This paper uses time series data from the Labor Force Survey (LFS) and Municipal Registers from 2000 to 2010 on population by country of birth and gender. The Spanish LFS (Encuesta de Población Activa, EPA) provides the most representative sample of the Spanish workforce during that time period. This survey is conducted every quarter by the National Statistics Institute (aka INE), and includes approximately 60,000 households (more than 200,000 individuals). Data from the Spanish LFS is crucial to investigate the characteristics of the labour force by country of birth and its gender composition. For calculations of occupational segregation, we use the 10-category major classification from the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO): (1) managers; (2) professionals; (3) technicians and associate professionals; (4) clerical support workers; (5) services and sales workers; (6) skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; (7) craft and related trades workers; (8) plant and machine operators and assemblers; (9) elementary occupations; and (10) armed forces occupations.

Population data for the analysis of residential segregation is derived from the administrative registers where municipality neighbours and in- and out-migrations are processed. This information is known as the Padrón Municipal de Habitantes or Municipal Registers, and is released on a yearly basis by INE. Since racial or ethnic categories are not used in surveys nor in census operations in Spain, our analysis is focused on the Spanish-born (native) population and immigrants (non-natives) who were born in one of the Latin America countries. All our analyses have a gender breakdown as the relationships between Latin American immigrants and natives, particularly in the labour market realm, are expected to be different for men and women (i.e. natives and immigrants are selected into occupations by gender).

While the smallest geography at which population data are published is the Secciones Censales or census tracts, with an average population of 1500 people per unit, data from the Spanish LFS has limited geographical detail and is only released for Autonomous Communities and provinces. In addition to this data limitation, there is a relatively small number of immigrant respondents in the LFS compared to natives for sub-national geographies. In order to prevent the small-unit bias problem that leads to overestimating the segregation level of groups with small samples at provincial level, we have implemented Iterative Proportional Fitting (IPF) to reasonably adjust our values for sub-national units (i.e. provinces) using the national samples for Latin American men and women separately.

The use of IPF ensures that our table by occupation and gender is scaled so that it agrees in its total with row and column totals supplied separately, thus allowing a combination of information from two data sets: the marginal totals from the national scale and the true cross-tabulated values from the provincial scale. Tables 5.1 and 5.2 contain our initial and estimated population counts across the 10 occupational categories by gender for the provinces of Madrid and Barcelona before and after IPF. The use of IPF allows an adjustment of the initial counts keeping each area’s specific gender pattern relative to other areas and bringing consistency with the national totals by occupation and gender.

Tables 5.1 and 5.2 show the initial table amended, in which IPF has performed the weighting process by repeating the one-dimensional scaling first to meet the national total by gender and then to meet the national total by occupation, then again the national total by gender, and so on iteratively. IPF brings the estimates closer and closer until they are consistent with both sets of marginal totals. In doing so, we increase our respective sample sizes while preserving the pattern of the original table (Bishop et al. 1975). Such features of IPF can be assessed by computing the cross-product ratios. For instance, if we take the four cells in the top left-hand corner of the original data in Table 5.1 for Madrid, and compute the cross-product ratio (i.e. (6)*(22)/(12)*(24)) the result is 0.4583. By applying the equivalent information from the cells of the estimated data using IPF (i.e. (38)*(90)/(75)*(99)), we obtain the same result.

IPF was originally presented by Deming and Stephan (1940) and has been included in standard statistical texts for many decades (Bishop et al. 1975). Versatile routines have been developed to handle any two-dimensional array in Excel (Norman 1999) and to tables of any dimensions applying loglinear procedures in SPSS (Simpson and Tranmer 2003). The use of IPF for census-based applications has been demonstrated by previous research (Birkin and Clarke 1995), and has proved very useful in demographic and geographical studies to make the age and sex structure for small populations consistent with more reliable data (Norman et al. 2008; Sabater and Simpson 2009). The mathematical definition of IPF in two dimensions follows the set of equations below (Wong 1992):

Where Pij (k) is the matrix element in row i, column j, and iteration k. Qi and Qj are the predefined row totals and column totals respectively. The new cell values are obtained by using Eqs. (5.1) and (5.2), which perform iteratively and stop at iteration m when:

For the calculation of residential segregation, one common measure was used Duncan and Duncan 1955b, the Dissimilarity Index (D). D remains the preferred measure when the subject of the analysis is the uneven distribution of members of two groups across a set of categories (occupational or spatial). Although there are alternative indices, the use of D is seen as relevant because it maintains continuity and allows straightforward comparisons both nationally and internationally Massey and Denton 1988. More specifically, D is used as the standard measure to analyse the uneven distribution of members of two groups (native and Latin American) by gender across a set of categories on both occupational and residential segregation. As a result, two analyses are undertaken in this paper, one relating residential segregation to occupational segregation of women, and a second relating residential segregation to occupational segregation of men. In this case, D is interpreted as the relative share of Latin American immigrants, separately for men and women, who would have to exchange occupations or neighbourhoods with Spanish natives in order to achieve even occupational and residential distributions. A common formula for the dissimilarity index is:

Where Nxi refers to the population of the Latin American group x of interest in occupation/neighbourhood i; g is the population of the reference group (Spanish natives); and the summation over an index is represented by the dot symbol. Multiplying by 100 expresses the share as a percentage, such that 0 indicates complete integration and 100 represents total segregation.

Finally, correlation analysis is undertaken using Pearson’s correlation (r) to evaluate the relationship between two continuous variables (i.e. segregation scores range from 0 to 100). The calculation of the Pearson Product-Moment Correlation coefficient (r), which is the magnitude of association between two continuous (interval/ratio) variables, can be expressed as follows:

The r value indicates the direction and magnitude of the correlation relationship between x and y, with a value between − 1 and + 1. Values closer to − 91 or 1 indicate a stronger relationship whereas values close to 0 indicate a weaker relationship. A positive r value indicates that a high value in one variable is associated with a high value in the other variable (or a low value in one variable is associated with a low value in the other variable). A negative r value indicates that a high value in one variable is associated with a low value in the other variable.

Results

Occupational Structure

Table 5.3 shows the percentage of total male and female for Latin Americans and Spanish natives in each ISCO-08 major group separately for Spain, Madrid and Barcelona in year 2010. The results of this table highlight that the relative size of the secondary segment of the labour market in Spain (occupations within major groups 5–9) is large for the total population (64.7 %) and even larger among Latin American immigrants (77.3 %). The results also reveal differences by gender, with a slightly greater proportion of Latin American women in low-status occupations (78 %) compared to men (76.6 %), a situation which is reversed for Spanish natives, with more men in the secondary segment (59.1 %) than women (45.2 %).

Examining the greatest percentages in each major occupation by gender (with more than 10 % of all employment), we denote how Latin American men are predominantly found among four major groups (27.9 % in craft and related trades workers, 19.3 % in elementary occupations, 14.1 % in services and sales workers and plant, and 12.4 % in machine operators and assemblers), whereas their female counterparts are mostly found in two major groups (42.1 % in elementary occupations, and 31.4 % in service and sales workers). The latter is in line with recent evidence from other studies suggesting that immigrant women experience a more intense occupational downgrading on arrival (Simón et al. 2014; Vidal-Coso and Miret 2014).

The results also illustrate that nearly two-thirds (60.7 %) of Latin American men are employed in occupations which require completion of the first stage of secondary education (ISCED-97 Level 2), whereas nearly a quarter (19.3 %) only need a minimum general level of education (ISCED-97 Level 1), and less than a quarter (18.8 %) are employed in occupations which demand a high-level of vocational qualification (ISCED-97 Level 3), a degree or equivalent qualification (ISCED-97 Level 4), or complex problem-solving, decision-making and creativity (ISCED-97 Levels 3 and 4). Although the picture for Latin American women is also shaped by a presence in occupations (predominantly services and sales workers) that require the first stage of secondary education (42.3 %), a significant group (elementary occupations) only need a minimum of general education (42.1 %). Indeed, a large percentage of Spanish natives can also be found in low-status occupations, with important gender differences too (21.5 % in craft and related trades workers among men, and 24.8 % in service and sales workers among women). However, there is clearly a much greater representation of employment across the occupational structure. For instance, more than one-third of all employment among Spanish natives for both men (34.2 %) and women (40.9 %) usually involve a degree or equivalent qualification, and/or relevant experience.

Although these results appear largely replicated in the metropolitan provinces of Madrid and Barcelona, there are some differences too. As can be observed, the proportion of Latin American workers employed in occupations which correspond to the secondary segment (occupations from 5 to 9) is larger among men in Madrid (78.3 %) compared to the national average (76.6 %), a situation that is also found among women in Barcelona (79.4 %) compared to the national average (78 %). Table 5.1 also makes evident that the ranking of occupations in the secondary segment for Latin American men and women in these two metropolitan areas also differs. While the groups of elementary occupations and service sales workers are ranked first and second for Latin American women in Madrid and Barcelona, only the group of craft and related trades workers for Latin American men shares the same (first) position in Madrid and Barcelona.

Of course, these are not the only differences between Madrid and Barcelona as there are also substantial ones in terms of how the occupational structure has evolved over time. Table 5.4 illustrates the occupational change (or mobility) for Latin American and Spanish natives by gender between years 2000 and 2010 in these two metropolitan labour areas and in Spain as a whole. As expected, the results make evident first a general tendency among Latin American men and women towards gaining representation in the low-status occupations while, at the same time, Spanish native men and women experience gains within higher status occupations and losses within low-status ones during this period.

However, we can also observe how there are exceptions to this pattern which clearly differ between the two metropolitan areas. For instance, examining first the changes over this 10 year period among Latin American women, we can denote how in Madrid women increased the proportional share of employment in the group of technicians and associate professionals between 2000 and 2010 by 9 % points–from 0 to 9 %-, while in Barcelona the same group slightly decreased–from 5.6 to 4.8 %. The table also allow us to see how Latin American women in Madrid decreased the proportional share of employment in the group of clerical support workers since year 2000 by 7.7 % points–from 13.7 to 6 %-, while the same group slightly increased in Barcelona–from 7 to 7.2 %. For males, we also observe different patterns in the two metropolitan areas. For example, in Madrid men increased the proportional share of employment in the group of clerical support workers between 2000 and 2010 by 3.9 % points–from 0 to 3.9 %-, while in Barcelona the same group decreased its size at the equivalent rate–from 6.2 to 2.3 %.

Apart from these opposite trends in Madrid and Barcelona, we also denote how the intensity of change varies considerably for those occupations with the largest shares. For instance, although the proportion of Latin American female employment in elementary occupations is higher in Madrid (45.9 %) than Barcelona (42.9 %), the analysis over time indicates that the proportional share has increased at a faster rate in Barcelona (by 8.7 % points) than Madrid (by 5.3 % points). Meanwhile, the proportion of Latin American male employment in the group of trade and related trades workers, which is slightly higher in Barcelona (30.2 %) than Madrid (27.9 %), appears to have increased at a faster rate in Barcelona (by 11.4 % points) than Madrid (by 7.3 % points).

Segregation Trends and Correlations

While taking a snapshot of occupational segregation may be useful to examine the distribution of people across occupations at one point in time, we focus on changes over time in order to assess trends toward integration or segregation. At the same time we evaluate the association between the two forms of segregation, occupational and residential, by computing zero-order correlation coefficients.

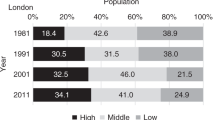

Figure 5.1 shows the evolution in occupational and residential segregation for Latin American men and women from 2000 through 2010. For this purpose, the index of dissimilarity (D) was computed across the 10 major occupational categories in Spain. For this exercise, we also display the values of residential segregation with a gender dimension in order to facilitate the interpretation of occupational segregation in comparison with residential segregation.

The results for D in occupation reveal differential trends in the degree of occupational integration achieved by Latin American men and women over time. On average, Latin American men in Spain experience a low level of occupational segregation, albeit it has slowly increased over time (from 18.4 in 2000 to 22.6 in 2010). In contrast, Latin American women not only experience a higher degree of occupational segregation (at 36); it also showed a sharp increase during the period of observation (going from 21.2 to 36). In other words, in 2010 roughly one-third of Latin American women in the labour force would have had to be reallocated to eliminate their overrepresentation in certain occupations and their underrepresentation in others in order to achieve a level of evenness comparable to their Spanish native counterparts. The results for D in the residential domain illustrate the opposite for Latin American men, who display higher values of dissimilarity than women, although in both cases the high-moderate level of segregation have been slowly declining over time (going from 44.6 in 2000 to 41.4 in 2010 for men; and from 41.4 in 2000 to 37.3 in 2010 for women). Thus, our results suggest that levels of occupational segregation are generally lower than residential segregation at national level for both men and women. However, it is worthy of note that that the levels of occupational and residential segregation for Latin American women are more similar and range within high-moderate levels whereas the values of occupational segregation among Latin American men are low compared to their high-moderate values of residential segregation.

Table 5.5 displays the results from the zero-order correlations and indicates that the basic pattern of association between occupational and residential segregation is similar for both men and women at national level, with a correlation coefficient which is − 0.895 for Latin American men and − 0.968 for Latin American women. Both correlations are statistically significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). These results would indicate that there is a relationship between the variables under investigation, and that the strength of such relationship is strong for both Latin American men and women, although the latter group (women) clearly display higher values, thus signalling the strongest relationship of the two. In principle, these results would support the idea that occupational and residential segregation are negatively correlated, thus suggesting that there is an inverse relationship between these two forms of segregation.

Figures5.2 and 5.3 show trends in occupational and residential segregation for Latin American men and women at metropolitan level in Madrid and Barcelona respectively between 2000 and 2010. The results for Madrid’s province clearly display how occupational dissimilarity among Latin American men rose significantly over the decade, going from 14.9 to 39.6. Although the increase among Latin American women was less steep, from 39.1 to 49.6, it is clear that the values of occupational segregation were already much higher, thus highlighting a greater level of unevenness across the occupational categories at the start of the period compared to their Spanish native counterparts. Interestingly, the rather marked rise in occupational segregation for Latin American men and women took place in a context of slowly increasing residential dissimilarity for Latin American men, from 30.1 to 32.7, and decreasing residential dissimilarity for Latin American women, from 28.7 to 28.

A similar picture is found at metropolitan level in Barcelona, albeit with some differences. First, Latin American men ended up at a similar level of occupational and residential dissimilarity in 2010 after a decade of increasing segregation in the labour market, going from 23.3 to 32.3, and decreasing segregation residentially, going from a peak of 40.6 to 31.8. Second, Latin American women experienced an increase in their level of occupational segregation during the decade, from 31.8 to 44.7, whereas their residential segregation fell steadily, going from a peak of 37.3 in 2000 to end the decade at 28.1 in 2010.

Finally, Table 5.6 and 5.7 show the results from the zero-order correlations at metropolitan level for Madrid and Barcelona. On the one hand, the results for Madrid reveal that the basic pattern of association between occupational and residential segregation is not similar for men and women, thus differing from the national picture. While Latin American men in Madrid display a weak correlation between occupational and residential segregation (0.204, and not statistically significant), Latin American women still highlight a strong correlation between the two (− 0.713, and statistically significant at the 0.01 level). On the other hand, the results for Barcelona illustrate a pattern of association similar to the national picture, with a correlation coefficient which is − 0.741 for Latin American men and − 0.841 for Latin American women. Both correlations are statistically significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

For men, the basic pattern of association between occupational and residential segregation is similar at national level and for the metropolitan area of Barcelona, albeit the relationship is always less strong. In sum, this analysis has shown that the zero-order association between two forms of segregation, occupational and residential, is negative and significant in most cases, thus highlighting that with a relatively extensive segregation of one form (occupational), the other form (residential) tends to be relatively low. However, it is worthy of note that while these results appear to support the hypothesis that there is an inverse relationship between occupational and residential segregation, it may be the case that after controlling for variables that affect both forms of segregation the correlation may also be nonsignificant or even positive. Therefore, it is important to treat these results with caution and as part of an initial explorative spatial data analysis.

In addition, a critical element in the overall description is to recognise that changes in occupational structure can incur a bias due to compositional effects or quality of immigrants arriving at different points in time (Borjas 1995); the business-cycle effects and correspondent entries and exits (Aslund and Rooth 2007); and the effect of return migration (Constant and Massey 2003; Dustmann and Weiss 2007). Unfortunately, an investigation of such effects falls outside the scope of this paper. However, given the recency of immigration in Spain and along with major economic restructuring, we can thus speculate that compositional, business-cycle and return migration will not change dramatically the overall description as the demand for ‘flexible labour’ and the expansion of jobs at the low end of the labour market are likely to continue to increase in the future (Cachón 2009).

Some Conclusions

Our analysis of occupational segregation in conjunction with residential segregation in Spain supports three basic conclusions. First, the degree of occupational segregation by Latin Americans has been shown to differ clearly by gender. While men experienced relatively low levels of occupational segregation, with a slow increase over time (from 18.4 in 2000 to 22.6 in 2010), women showed much higher levels of occupational segregation as well as sharp increase during the period of study (from 21.2 to 36) in Spain as a whole. These results clearly contrast with those from the residential domain in which men display higher values of dissimilarity than women, and overall values of residential segregation indicate a slow decline for both genders (going from 44.6 in 2000 to 41.4 in 2010 for men; and from 41.4 in 2000 to 37.3 in 2010 for women).

Second, despite the ecological differences, the variation in sex composition of occupational categories and the differential occupational structure of the economy between Madrid and Barcelona, the respective patterns and trends in residential and occupational segregation yield similar conclusions for both metropolitan areas: in each case, the level of occupational dissimilarity among Latin American women is considerably greater compared to Latin American men; and residential segregation has tended to decline over time, with the exception of Latin American men in Madrid.

Third, consistent with these broad trends, a correlation analysis at national level supports the idea that, contrarily to the parsimony hypothesis (i.e. positive correlation), occupational and residential segregation are negatively correlated for both men and women, thus suggesting that there is an inverse relationship between these two forms of segregation. While these results are largely replicated in the metropolitan province of Barcelona, they differ slightly in Madrid, where a weak and non-significant correlation between occupational and residential segregation is found among men. Overall, the national picture as well as the results for Madrid and Barcelona would, however, suggest that areas with low levels of female residential segregation tend to have high levels of occupational segregation.

Finally, the findings suggest that the use of IPF is a valid tool to maximise small samples of population by occupation and gender from the Spanish LFS for the provinces of Madrid and Barcelona while keeping each area’s original specific pattern. IPF has been extensively used when reliable counts or estimates for a desired cross-classification cannot be obtained directly but counts or estimates of the variables of interest are available at a higher level of aggregation. Although IPF can also be used to derive populations by occupation and gender for particular immigrant groups, the initial counts for these populations are too small at national level that producing sub-national estimates is not advisable. Nonetheless, further investigation is being carried out to derive estimates for Latin American men and women for smaller areas such as municipalities using the available information from the Spanish LFS at national and provincial level, and the population data with detail of country of birth and gender from Municipal registers.

Discussion

It is widely accepted that different forms of social structures affect economic action of immigrant communities (Wilson 1987; Massey and Denton 1993) and that the actual experience of socio-spatial segregation of a demographic group depends on the characteristics of the local labour market in which the group works (Ellis et al. 2007; Wright et al. 2010). Within this context, the relationship between globalisation and externalisation of reproductive work, a complex way in which gender, race and immigration interact (Calavita 2006), continues to play a crucial role in the social and labour integration, particularly among Latin American women in Spain (Díaz et al. 2012). As Domínguez-Mujica (2014, p 379) notes, “structural factors such as population ageing, the lesser development of social services and patriarchal family values, favour the externalization of reproductive work and contribute to consolidation of this labour niche”.

Our findings highlight that Latin Americans, particularly women, clearly suffer extensive occupational discrimination but limited residential segregation. This negative correlation between occupational and residential segregation is probably the worst-case scenario in the policy arena because it suggests that both sets of segregation do not derive from a single underlying system of inequality, and reflect multidimensinal issues which demand specific target policies, particularly in the labour market realm. However, the extensiveness of labour market specialisation of Latin Americans and immigrants in general, and among women in particular, points to institutional practices and public policies that, in fact, both facilitate and, to some degree, create the conditions of occupational segregation. Therefore, although the reduction of residential segregation between Latin Americans and Spanish natives represents ‘good news’, this should not distract policymakers from dedicating greater efforts to mitigate a triple discrimination in the labour market—based on gender, ethnos and class—that acts as a highly restrictive factor in terms of immigrants’ choice (Santamaría 2009).

A large body of research conducted over the past decade (see, among others Cachón 2002, 2009; Domingo and Gil-Alonso 2007; Amuedo-Dorantes and De la Rica 2007; Fernández and Ortega 2008; Izquierdo et al. 2009; Bernardi et al. 2011; Simón et al. 2014; Vidal-Coso and Miret 2014; Vidal-Coso and Vono-de-Vilhena, this book) clearly indicate that increasing polarisation in the Spanish labour market is leading to a complementarity process between Spanish natives and the immigrant population. Unfortunately, such processes appear to be at the expense of growing occupational disadvantage for the immigrant population, particularly among female migrants. Our findings are in keeping with previous results, and highlight the importance of documenting trends in residential and occupational segregation sub-nationally over time. If ethnic niching becomes a more permanent issue in Spain, it is likely that this will affect not only the first generation but also subsequent generations and, therefore, there could be a knock-on effect on the current residential de-segregation. In this regard, one can speculate that the immediate spatial dispersal enjoyed by Latin Americans will probably count for very little if their descendants are re-segregated in socioeconomic terms.

References

Aja, E., & Arango, J. (Eds.). (2006). Veinte años de inmigración en España. Barcelona: CIDOB.

Akresh, I. R. (2006). Occupational mobility among legal immigrants to the United States. International Migration Review, 40(4), 854–884.

Akresh, I. R. (2008). Occupational trajectories of legal US immigrants: Downgrading and recovery. Population and Development Review, 34(3), 435–456.

Alcobendas, M., & Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2009). Immigrants’ assimilation process in a segmented labor market. IZA Discussion Paper Series, 4394, Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & De la Rica, S. (2007). Labour market assimilation of recent immigrants in Spain. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 257–284.

Anthias, F., & Lazaridis, G. (2000). Gender and migration in Southern Europe. Women on the move. Oxford: Berg.

Arango, J., & Finotelli, C. (2009). Spain. In M. Baldwin-Edwards & A. Kraler (Eds.), REGINE Regularisations in Europe. Study on practices in the area of regularisation of illegally staying third-country nationals in the member states of the EU. Vienna: ICMPD.

Arjona, A. (2007). Ubicación espacial de los negocios étnicos en Almería. ¿Formación de enclaves económicos étnicos? Estudios geográficos, 68(263), 391–415.

Aslund, O., & Rooth, D. O. (2007). Do when and where matter? Initial labour market conditions and immigrant earnings. The Economic Journal, 117(518), 422–448.

Bayona, J. (2007). La segregación residencial de la población extranjera en Barcelona: ¿una segregación fragmentada? Scripta Nova, 11(235). http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-235.htm. Accessed 25 October 2014.

Bayona, J., & Gil-Alonso, F. (2012). Suburbanisation and international immigration: The case of the Barcelona metropolitan region. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 103(3), 312–329.

Beltrán, J., Oso, L., & Ribas, N. (Eds.). (2006). Empresariado étnico en España, Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales. Observatorio Permanente de la Inmigración.

Bernardi, F., & Garrido, L. (2008). Is there a new service proletariat? Post-industrial employment growth and social inequality in Spain. European Sociological Review, 24(3), 299–313.

Bernardi, F., Garrido, L., & Miyar, M. (2011). The recent fast upsurge of immigrants in Spain and Their Employment Patterns and Occupational Attainment. International Migration, 49(1), 148–187.

Birkin, M., & Clarke, G. (1995). Using microsimulation methods to synthesise census data. In S. Openshaw (Ed.), Census users’ handbook (pp. 363–387, Chapter 12). Cambridge: GeoInformation International.

Bishop, Y. M., Fienberg, S. E., & Holland, P. W. (1975). Discrete multivariate analysis: Theory and practice. Cambridges: MIT.

Borjas, GJ. (1995). Assimilation and changes in cohort quality revisited: What happened to immigrant earnings in the 1980s? Journal of Labor Economics, 13(21), 201–245.

Cachón, L. (2002). La formación de la ‘España inmigrante’: mercado y ciudadanía. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 97(2), 95–126.

Cachón, L. (2009). La ‘España inmigrante’: marco institucional, mercado de trabajo y políticas de integración. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Calavita, K. (2006). Gender, migration and law: Crossing borders and bridging disciplines. International Migration Review, 40(1), 104–132.

Cebolla, H., & González-Ferrer, A. (2008). La inmigración en España (2000–2007). Del control de flujos a la integración de inmigrantes. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales.

Chiswick, B. R. (1978). The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. Journal of Political Economy, 85(5), 897–921.

Chiswick, B. R., Lee, Y. L., & Miller, P. W. (2005). A longitudinal analysis of immigrant occupational mobility: A test of the immigrant assimilation hypothesis. International Migration Review, 39(2), 332–353.

Clark, WAV. (1992). Residential preferences and residential choices in a multi-ethnic context. Demography, 29(3), 451–466.

Constant, A., & Massey, D. (2003). Self-selection, earnings, and out-migration: A longitudinal study of immigrants to Germany. Journal of Population Economics, 16(4), 631–653.

Deming, W., & Stephan, F. (1940). On a least squares adjustment of a sampled frequency table when the expected marginal tables are known. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 11(4), 427–444.

Díaz, E. M., Gallardo, F. C., & Castellani, S. (2012). Latin American immigration to Spain. Cultural Studies, 26(6), 814–841.

Domingo, A., & Gil-Alonso, F. (2007). Immigration and changing labour force structure in the Southern European Union. Population, 62(4), 709–727 (English edition).

Domínguez-Mujica, J. (2014). The enduring connection between gender, migration and household services. Geographia Polonica, 87(3), 367–382.

Donato, K. M. (2006). A glass half full? Gender in migration Studies. International Migration Review, 40(1), 3–26.

Donato, K. M., Alexander, J. T., Gabaccia, D. R., & Leinonen, J. (2011). Variations in the gender composition of immigrant populations: How they matter. International Migration Review, 45(3), 495–526.

Duncan, O. D., & Duncan, B. (1955a). Residential distribution and occupational stratification. American Journal of Sociology, 60(5), 493–503.

Duncan, O. D., & Duncan, B. (1955b). A methodological analysis of segregation indices. American Sociological Review, 20(2), 210–217.

Duncan, O., & Lieberson, S. (1959). Ethnic Segregation and Assimilation. American Journal of Sociology, 64(4), 364–374.

Dustmann, C., & Weiss, Y. (2007). Return migration: Theory and empirical evidence from UK. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 236–256.

Echazarra, A. (2010). Segregación residencial de los extranjeros en el área metropolitana de Madrid. Un análisis cuantitativo. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 68(1), 165–197.

Ellis, M., Wright, R., & Park, V. (2004). Work together, live apart? Geographies of racial and ethnic segregation at home and at work. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 94(3), 620–637.

Ellis, M., Wright, R., & Parks, V. (2006). The immigrant household and spatial assimilation: Partnership, nativity, and neighborhood location. Urban Geography, 27(1), 11–19.

Ellis, M., Wright, R., & Parks, V. (2007). Geography and the immigrant division of labour. Economic Geography, 83(3), 255–282.

Ellis, M., Holloway, S. R., Wright, R., & Fowler, C. S. (2012). Agents of change: Mixed-race households and the dynamics of neighborhood segregation in the United States. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(3), 549–570.

Fernández, C., & Ortega, C. (2008). Labour market assimilation of immigrants in Spain. Spanish Economic Review, 10(2), 83–107.

Friedberg, RM. (2000). You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2), 221–251.

Galeano, J., Sabater, A., & Domingo, A. (2014). Formació i evolució dels enclavaments ètnics a Catalunya abans i durant la crisi económica. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 60(2), 261–288.

Galster, G. C., & Keeney, W. M. (1988). Race, residence, and economic opportunity: Modeling the Nexus of urban racial phenomena. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 24(1), 87–117.

Glasmeier, A. K., & Farrigan, T. L. (2007). Landscapes of inequality: Spatial segregation, economic isolation, and contingent residential locations. Economic Geography, 83(3), 221–230.

Gober, P. (2000). Immigration and North American cities. Urban Geography, 21(1), 83–90.

González-Ferrer, A. (2011). Explaining the labour performance of immigrant women in Spain: The interplay between family, migration and legal trajectories. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 52(1–2), 63–78.

Hierro, M. (2013). Latin American migration to Spain: Main reasons and future perspectives. International Migration (online version only).

Holloway, S. R., Ellis, M., Wright, R., & Hudson, M. (2005). Partnering ‘out’ and fitting in: Residential segregation and the neighbourhood contexts of mixed-race households. Population, Space and Place, 11(4), 299–324.

Izquierdo, A., & Martínez, R. (2003). La inmigración en España en 2001. In A. Izquierdo (Ed.), Inmigración: mercado de trabajo y protección social en España (pp. 99–181). Madrid: CES, Colección Estudios.

Izquierdo, A., López de Lera, D., & Martínez Buján, R. (2003). The favorites of the twenty-first century: Latin American immigration in Spain. International Journal of Migration Studies, 149(40), 98–125.

Izquierdo, M., Lacuesta, A., & Vegas, R. (2009). Assimilation of immigrants in Spain: A longitudinal analysis. Labour Economics, 16(6), 669–678.

Kaplan, D. H. (1998). The spatial structure of urban ethnic economies. Urban Geography, 19(6), 1489–1501.

King, R., Lazaridis, G., & Tsardanidis, C. (2000). Eldorado or fortress? Migration in Southern Europe. London: Macmillan.

Light, I. (1998). Afterword: Maturation of the ethnic economy paradigm. Urban Geography, 19(6), 577–579.

Light, I., & Bonacich, E. (1988). Immigrant entrepreneurs: Koreans in Los Angeles, 1965–1983. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Light, I. H., & Gold, S. J. (2000). Ethnic Economies. San Diego: Academic.

Logan, J. R., Alba, R. D., & Zhang, W. Q. (2002). Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 299–322.

López-Sala, A. (2013). Managing uncertainty: Immigration policies in Spain during economic recession (2008–2011). Migraciones Internacionales, 7(2), 39–69.

Lutz, H. (2008). Migration and domestic work. A European perspective on a global theme. Surrey: Ashgate.

Martori, J. C., & Apparicio, P. (2011). Changes in spatial patterns of the immigrant population of a Southern European metropolis: The case of the Barcelona metropolitan area (2001–2008). Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 102(5), 499–630.

Massey, D. S. (1985). Ethnic residential segregation: A theoretical synthesis and empirical review. Sociology and Social Research, 69(3), 315–350.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1988). The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces, 67(2), 281–315.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Massey, D. S., Gross, A. B., & Eggers, M. L. (1991). Segregation, the concentration of poverty, and the life chances of Individuals. Social Science Research, 20(4), 397–420.

Massey, D. S., Fischer, M. J., & Capoferro, C. (2006). International migration and gender in Latin America: A comparative analysis. International Migration, 44(5), 63–91.

Norman, P. (1999). Putting iterative proportional fitting on the researcher’s Desk. Working Paper. School of Geography, University of Leeds.

Norman, P., Simpson, L., & Sabater, A. (2007). ‘Estimating with Confidence’ and hindsight: New UK small area population estimates for 1991. Population, Space and Place, 14(5), 449–472.

Ovadia, S. (2003). The dimensions of racial inequality: Occupational and residential segregation across metropolitan areas in the United States. City and Community, 2(4), 313–333.

Parks, V. A. (2004). The gendered connection between ethnic residential and labour market segregation in Los Angeles. Urban Geography, 25(7), 589–630.

Peck, J. (1996). Workplace: The social regulation of Labor Markets. New York: Guilford.

Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2001). Contingent Chicago: Restructuring the spaces of temporary labor. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(3), 471–496.

Peixoto, J. (2009). Back to the south: Social and political aspects of Latin American migration to Southern Europe. International Migration, 50(6), 58–82.

Piore, M. J. (1979). Birds of passage: Migrant labor in industrial Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Portes, A., & Bach, R. L. (1985). Latin journey: Cuban and Mexican immigrants in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Portes, A., & Sensenbrenner, J. (1993). Embeddendness and immigration: Notes on the social determinants of economic action. American Journal of Sociology, 96(6), 1320–1350.

Portes, A., & Shafer, S. (2007). Revisiting the enclave hypothesis: Miami twenty-five years later. Research in the Sociology of Organisations, 25, 175–190.

Riesco, A. (2008). ¿Repensar la sociología de las economías étnicas? El caso del empresario inmigrante en Lavapiés. Migraciones, 24, 91–134.

Sabater, A., & Domingo, A. (2012). A new immigration regularisation policy: The settlement programme in Spain. International Migration Review, 46(1), 191–220.

Sabater, A., & Simpson, L. (2009). Enhancing the population census: A time series for sub-national areas with age, sex and ethnic group dimensions in England and Wales, 1991–2001. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(9), 1461–1477.

Sabater, A., Bayona, J., & Domingo, A. (2012). Internal migration and residential patterns across Spain after unprecedented international migration. In N. Finney & G. Catney (Eds.), Minority internal migration in Europe (pp. 293–311). Surrey: Ashgate.

Santamaría, L. C. (2009). La mercantilización y mundialización del trabajo reproductivo. El caso español. Revista de Economía Crítica, 7, 74–94.

Schrover, M., van der Leun, J., & Quispel, C. (2007). Niches, labour market segregation, ethnicity and gender. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(4), 529–540.

Serra, P. (2012). Global businesses ‘from Below’: Ethnic entrepreneurs in metropolitan areas. Urban challenge (Urbani izziv), 23(s2), 97–106.

Simón, H., Ramos, R., & Sanromá, E. (2014). Immigrant occupational mobility: Longitudinal evidence from Spain. European Journal of Population, 30(2), 223–255.

Simpson, L., & Tranmer, M. (2003). Combining sample and census data in small area estimates: Iterative proportional fitting with standard software. Professional Geographer, 57(2), 222–234.

Solé, C., & Parella, S. (2005). Los negocios étnicos: Los comercios de los inmigrantes no comunitarios en Cataluña. Barcelona: Fundació CIDOB.

Stanek, M., & Veira, A. (2012). Ethnic niching in a segmented labour market: Evidence from Spain. Migration Letters, 9(3), 249–262.

Vidal-Coso, E., & Miret, P. (2013). The internationalitation of domestic work and female immigration in Spain during a decade of economic expansion, 1999–2008. In L. Oso & N. Ribas-Mateos (Eds.), International handbook of gender, migration and transnationalism. Global and development perspectives (pp. 337–360). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Vidal-Coso, E., & Miret, P. (2014). The labour trajectories of immigrant women in Spain: Are there signs of upward social mobility? Demographic Research, 31(13), 337–380.

Vono-de-Vilhena, D., & Vidal-Coso, E. (2012). The impact of informal networks on labour mobility: Immigrants’ first job in Spain. Migration Letters, 9(3), 237–247.

Waldinger, R. (1996). Still the promised city? African Americans and new immigrants in postindustrial New York. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wang, Q. (2006). Linking home to work: Ethnic labour market concentration in the San Francisco CMSA. Urban Geography, 27(1), 72–92.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Wilson, F. D. (2003). Ethnic niching and metropolitan labor markets. Social Science Research, 32(3), 429–466.

Wilson, F. D., & Hammer, R. B. (2001). The causes and consequences of racial residential segregation. In A. O’Connor, C. Tilly, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Urban inequality in the United States: Evidence from four cities (pp. 272–303). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wilson, K., & Portes, A. (1980). Immigrant enclaves: An analysis of the labor market experiences of Cubans in Miami. American Journal of Sociology, 86(2), 295–319.

Wong, D. (1992). The Reliability of Using the Iterative Proportional Fitting Procedure. The Professional Geographer, 44(3), 340–348.

Wright, R., & Ellis, M. (1997). Nativity, ethnicity and the evolution of the intra-urban division of labour in metropolitan Los Angeles, 1970–1990. Urban Geography, 18(3), 243–263.

Wright, R., & Ellis, M. (2000). The ethnic and gender division of labor compared among immigrants to Los Angeles. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(3), 583–600.

Wright, R., Ellis, M., & Parks, V. (2010). Immigrant niches and the intrametropolitan spatial division of labour. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(7), 1033–1059.

Zelinsky, W., & Lee, B. A. (1998). Heterolocalism: An alternative model of sociospatial behaviour of immigrant ethnic communities. International Journal of Population Geography, 4(4), 281–298.

Zubrinsky Charles, C. (2001). Processes of racial residential segregation. In A. O’Connor, C. Tilly, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Urban inequality in the United States: Evidence from four cities (pp 217–271). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sabater, A., Galeano, J. (2015). The Nexus Between Occupational and Residential Segregation. In: Domingo, A., Sabater, A., Verdugo, R. (eds) Demographic Analysis of Latin American Immigrants in Spain. Applied Demography Series, vol 5. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12361-5_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12361-5_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-12360-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-12361-5

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)