Abstract

Single parenthood , resulting from nonmarital births and divorce , is increasingly becoming associated with lower levels of education for women. Cross-sectional comparisons show that children of married parents are less likely to suffer material deprivation. To reduce hardships for children, therefore, some analysts advocate policies that would increase marriage rates . I argue that alternative approaches offer more chance of success: increasing education levels and reducing the penalty for single parenthood. There is ample evidence to support both alternative approaches. Education levels are increasing and are associated with lower levels of child hardship net of family structure . And comparative research shows the negative economic consequences of single parenthood are ameliorable through state policy. In contrast, the hundreds of millions of dollars spent promoting marriage, and the reform of national welfare policy intended to compel poor mothers to marry, have produced no discernible effects on marriage rates or child well-being .

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Divergent Responses to Family Inequality

McLanahan and Jacobsen (Chap. 1 ) express concern that family patterns associated with poverty —single motherhood, early age at first birth , mothers’ non-employment , and divorce —are becoming increasingly associated with lower levels of education. The apparent effect of these trends is to concentrate disadvantage among children who not only have parents with low levels of education, but who also have family structures and trajectories that are not conducive to escaping poverty and its harms.

Although they focus on several trends , the core issue is single motherhood, and that is the focus of this comment. Single motherhood occurs through the birth of children to women who are not married—which continues to become more prevalent, especially among younger women and those with relatively low education (Martin et al. 2013)—and through divorce , which is concentrated among couples with lower levels of education (Cohen 2014). To reverse that trend, McLanahan and Jacobsen (Chap. 1) suggest, first, a family intervention: giving less-educated women “a good reason to postpone motherhood” (p. 21). Their second recommendation is to “improve the economic prospects of men, especially men with no more than a high school degree ,” because “[w]omen are not likely to marry men whom they view as poor providers” (p. 21). Although this second recommendation focuses on economics, McLanahan and Jacobsen favor it because it will decrease the prevalence of single motherhood, concluding, “nothing could be more important for preserving the institution of marriage” (p. 22). Thus, in response to the trends by which “the second demographic transition is leading to growing disparities in children’s access to parental resources ,” McLanahan and Jacobsen seek to alter family structure, to reduce single parenthood. The approach they propose, however, is just one of several logical responses to family inequality —and the one that recent history suggests is not likely to succeed. I illustrate their argument in Fig. 2.1. In Fig. 2.1, McLanahan and Jacobsen’s “diverging destinies” appear as increases in b/b′ over time, or the increasing tendency of women with low levels of education to engage in “behaviors associated with poor child outcomes.” That is, in addition to the direct effects of mothers’ education on child outcomes (through income and other resources, labeled e), family behaviors exacerbate social class inequality. Changing the family behavior of the low-education group is their proposed response. Logically, however, to reduce harm to children, we might consider two alternative approaches: (1) promote the flow labeled a, which moves more women into the highly educated category or (2) reduce the quantity d, which indicates the negative outcomes associated with single motherhood. I discuss these alternatives first.

“Diverging destinies.” The McLanahan/Jacobsen strategy is to decrease b/b′ (decrease the tendency of low-education women to engage in “bad” family behavior). Alternatives include increasing a (moving women into the high-education group) or reducing d (mitigating the harms associated with “bad” family behavior)

Increase Education

All else equal, it is probably safe to assume that further increasing education levels for women would lead to fewer nonmarital births . That is both because women with higher education have fewer children and because they are more likely to do so after marrying (Table 2.1). Of course, unmarried parenthood has continued to increase despite women’s rising education levels. But poverty among the children of single mothers has no doubt been reduced by the increasing likelihood that their mothers will have education beyond high school.

This may be illustrated with a few simple statistics (Table 2.2). The proportion of single mothers with bachelor’s degrees reached 18.9 % in 2013, and those with college degrees are much less likely to be poor. Only 18.2 % of college-graduate single mothers live below 150 % of the official poverty line , compared with 52 % for those who have not complete college. These education patterns simply suggest that more education for women would increase total child well-being by reducing single motherhood and its associated hardships—that is, through both c and e in Fig. 2.1. That may seem a banal conclusion, but it is one that somehow is not part of McLanahan and Jacobsen’s (Chap. 1) recommendations, as they focus on changing family structure .

The determinants of educational attainment and related policies are outside of my expertise, so after this brief discussion, I now turn to the consequences of single motherhood.

Reduce the Penalty for Single Motherhood

Single motherhood need not lead to inequality and hardship. Some single mothers are poor and some are not, and the negative outcomes statistically associated with single motherhood are much more related to material deprivation than they are to family structure itself. As McLanahan wrote two decades ago:

For children living with a single parent and no stepparent, income is the single most important factor in accounting for their lower well-being as compared with children living with both parents. It accounts for as much as half of their disadvantage. Low parental involvement, supervision, and aspirations and greater residential mobility account for the rest (McLanahan 1994, p. 134).

Because single motherhood and poverty are highly correlated for children at a single point in time, and because poverty in one generation is highly correlated with poverty in the next, many people assume that growing up with a single mother—independent of its association with income—leads to poverty in adulthood. Careful longitudinal studies find this is not true, however. Musick and Mare, using the National Longitudinal Surveys to examine women born in the 1960s, conclude:

Net of the association between poverty and family structure within a generation, the intergenerational transmission of poverty is significantly stronger than the intergenerational transmission of family structure , and neither childhood poverty nor family structure affects the other in adulthood (Musick and Mare 2006, p. 490).

Holding constant poverty status in adolescence, in other words, having lived with a single mother in adolescence did not increase the odds of a woman being in poverty when she reached adulthood. The unadjusted pattern from Musick and Mare’s paper is shown in Fig. 2.2. Other research, such as that assessing school readiness , finds similar patterns in the cross section (Condron 2007; Denton et al. 2009).

Percent poor among adult mothers, by family structure and poverty level in adolescence. Source My calculations, combining Black and White mothers, from Musick and Mare (2006)

Of course, if single mothers are poor, and their children experience the harms associated with that, the knowledge that such harms result more from economic status than from family structure provides cold comfort. From a policy perspective, however, that insight suggests that such travails are largely preventable by policy strategies that provide jobs or income supports. Despite the challenges single-parent families face, poverty need not be one of them: The effect d in Fig. 2.1 is mutable.

Cross-national research confirms this. Consider the poverty gap between single-parent and married-parent families. Several analyses of relative poverty across family types in Europe, Canada, and the USA find that single mothers in the USA are much more likely to have incomes below half the median, after accounting for income taxes and transfers, than those in these other rich countries (Brady and Burroway 2012; Misra et al. 2007). For example, Brady and Burroway found that not only did the USA have the highest poverty rate for single mothers among these countries (41 %), but it also had one of the largest differences in relative poverty rates between single-mother families and the population overall (24 % points). In contrast, in the Nordic countries, single mothers had poverty rates less than 5 % points higher than the population at large (Fig. 2.3).

Poverty rate for single mothers and overall poverty rate in 10 countries. Source Brady and Burroway (2012)

Reducing the hardships associated with single parenthood is not a complicated proposition. The failure of basic needs provision for poor families is so stark that virtually any intervention seems likely to improve their well-being. Among single-mother families, more than one-in-three report each of food hardship, healthcare hardship, and bill-paying hardship in the previous year (Eamon and Wu 2011). Poor families, especially those with a single parent, need more money, which may come from a (better-paying) job, an income subsidy, or in-kind support such as food support.

Change Family Structure

There is no denying that single-parent families have high poverty rates. Would not redirecting trends in family structure reduce child poverty and hardship and do it in a more politically feasible way than increasing welfare or jobs programs, given Americans’ distaste for welfare programs? Of course, changing family structure is the longstanding goal of federal welfare policy . The 1996 welfare reform was premised on the necessity of “prevention of out-of-wedlock pregnancy and reduction in out-of-wedlock birth .” Indeed, the first “finding” of the law was, “(1) Marriage is the foundation of a successful society” (Public Law 104–193, 1996). In the service of this ideological assertion (one that cannot be empirically assessed), the federal government has spent hundreds of millions of dollars attempting to promote marriage among the poor—money that came from the federal welfare program (Heath 2012).

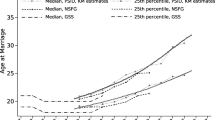

The result, given the size of the effort, can only be described as a spectacular failure. Welfare reform did increase employment rates (Sayer et al. 2004), but it did nothing to change the direction of family structure trends. Program evaluations show that marriage intervention programs have had no measurable effect on marriage rates (Wood et al. 2010). And of course, marriage rates in the population have continued their long-run decline (Cohen 2013), most especially for those without college degrees . As Fig. 2.4 shows, those without college degrees in the 2000s experienced an accelerating drop in the percentage married.

There is simply no precedent to support the idea that government policy can reverse the long-run decline in marriage, or the increase in non-marital childbearing . And the advocates of such policies offer no evidence to support the idea that such a policy might work in the future. In contrast, we have voluminous evidence that such efforts do not work—and that they often come with religious or ideological baggage that selectively impose upon the freedoms and integrity of poor people and their families (Heath 2012).

The rise of women’s independence, along with the decline in marriage and fertility , are interrelated parts of modern social development. And the overall consequence of these trends must be deemed positive—as life expectancies have increased, absolute poverty has decreased, and gender inequality has receded. The delay in age at marriage and the extension of divorce rights have no doubt prevented or ended many unhappy or unsafe marriages , even as they have carried risks. But the advocates for marriage offer no attempt to specify the ideal marriage rate. How are we to know that the decline in marriage has gone too far? The unwavering advocacy for more marriage, in the face of its continued inefficacy and impracticality, dissolves into ideology and distracts from the important challenges we face in attempting to improve the quality of life for poor families and their children.

References

Brady, D., & Burroway, R. (2012). Targeting, universalism, and single-mother poverty: A multilevel analysis across 18 affluent democracies. Demography, 49(2), 719–746. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0094-z.

Cohen, P. N. (2013, June 4). How to live in a world where marriage is in decline. The Atlantic.com. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/06/how-to-live-in-a-world-where-marriage-is-in-decline/276476/

Cohen, P. N. (2014). Recession and divorce in the United States, 2008–2011. Population Research and Policy Review. doi:10.1007/s11113-014-9323-z

Condron, D. J. (2007). Stratification and educational sorting: Explaining ascriptive inequalities in early childhood reading group placement. Social Problems, 54(1), 139–160. doi:10.1525/sp.2007.54.1.139.

Denton Flanagan, K., & McPhee, C. (2009). The children born in 2001 at kindergarten entry: First findings from the kindergarten data collections of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) (NCES 2010-005). Washington: U.S. Department of Education, NCES.

Eamon, M. K., & Wu, C. F. (2011). Effects of unemployment and underemployment on material hardship in single-mother families. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(2), 233–241. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.09.006.

Heath, M. (2012). One marriage under God: The campaign to promote marriage in America. New York: New York University Press.

Martin, J., Hamilton, B., Ventura, S., Osterman, M., & Mathews, T. (2013). Births: Final data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports, 62(1), 1–69.

McLanahan, S. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Misra, J., Moller, S., & Budig, M. J. (2007). Work-family policies and poverty for partnered and single women in Europe and North America. Gender and Society, 21(6), 804–827. doi:10.1177/0891243207308445.

Musick, K., & Mare, R. D. (2006). Recent trends in the inheritance of poverty and family structure. Social Science Research, 35(2), 471–499. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.11.006.

Wood, R. G., McConnell, S., Moore, Q., Clarkwest, A., & Hsueh, J. A. (2010). Strengthening unmarried parents’ relationships: The early impacts of building strong families. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/15_impact_exec_summ.pdf

Sayer, L. C., Cohen, P. N., & Casper, L. M. (2004). The American people: Women, men, and work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

U.S. Census Bureau, D. I. S. (n.d.-a) 2012. Educational attainment in the United States: Detailed tables. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/2012/tables.html

U.S. Census Bureau, D. I. S. (n.d.-b). 2010. Fertility of American women: Detailed tables. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/fertility/data/cps/2010.html

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Lucia Lykke for research assistance. Some parts of this analysis appeared earlier on my blog, Family Inequality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cohen, P.N. (2015). Divergent Responses to Family Inequality. In: Amato, P., Booth, A., McHale, S., Van Hook, J. (eds) Families in an Era of Increasing Inequality. National Symposium on Family Issues, vol 5. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08308-7_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08308-7_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-08307-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-08308-7

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)