Abstract

This study followed the online activity on Twitter during Pakistan’s landmark 2013 General Election, also hailed as Pakistan’s first Twitter election, which marked the first ever transfer of power between two elected civilian governments. This election saw the unexpected emergence of Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI), the political underdog which followed close at the heels of well-established dynastic parties to grab the third-largest number of seats in the National Assembly. The rise of this party and its leader is attributed to the estimated 30 million young Pakistanis who voted for the first time and the advent of social media, as well as the leadership of Imran Khan, the most famous sports celebrity in the country. This study focused on the Twitter campaigns of Pakistan’s political parties with the aim to investigate how the medium was used by political parties for information dissemination, interaction, mobilization and engagement of voters. Our investigation was related and discussed in the context of the actual success achieved by each party. The approach followed was systematic automatic and manual content analyses and a social network analysis of the tweets (n = 10,140) posted by the top four political parties and their leaders in the month leading up to Pakistan’s general election. Our findings identify that every party used Twitter for different purposes. PTI used Twitter in the most diverse ways—they interacted with voters, provided real time detailed campaign updates, discussed specific social and political issues and called for a greater mobilization of citizens to vote. Through triangulation of our findings with the publically available election data provided by the Election Commission of Pakistan we further conclude that the success story of PTI, especially at the provincial level, was a blend of the party riding on personality politics paradigm with a combination of an increase in voter turnout and strategized online-offline campaigning targeted at the youth.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

9.1 Introduction

Twitter, the social networking tool, has emerged to be a powerful medium to connect, influence and engage its audience. Political landscapes throughout the world have been affected or altered by the political force which is Twitter; the uprisings in MENA region are an example. There is a radical transformation in the ways citizens and governments connect with each other. The design of the Twitter platform allows citizens to interact with each other, exchange messages enmasse and participate in a global debating arena. On the other hand, the medium also provides governments and politicians with an opportunity to connect with the citizens in new and effective ways and in the process eliminates the heavily mediated communication offered by the traditional media (Harfoush 2009; Posetti 2011). Appreciating this fact, politicians across the world have openly embraced Twitter; academic research too has established how Twitter has been extensively used by political candidates in United States of America (Christensen 2013; Conway et al. 2013; Hong and Nadler 2011), United Kingdom (Graham et al. 2013), Finland (Strandberg 2013), Sweden (Grusell and Nord 2011), Australia (Bruns and Highfield 2013) and New Zealand (O’Neill 2010) to connect and reach a wide audience base.

However, much of the exploits of Twitter as a political engagement tool have been in technologically advance democratic societies with high Internet accessibility and a large numbers of new media users. The usage of the medium for politician-citizen exchanges in a country like Pakistan, with low Internet penetration rates and the looming threat of terrorist attacks, has never been explored before. Because of the dangers to lives in face-to-face campaigning, Twitter plays a special role—as a convenient refuge and a more secure platform to connect with citizens. It is here we present a study first of its kind—investigating the usage of Twitter as a political engagement and campaign tool for Pakistan political parties and their leaders during the 2013 General Election.

Pakistan is an interesting case study for several reasons. Since its creation in 1947, Pakistan, the fifth largest democracy in the world, has seen three periods of martial law, extra-constitutional removal of civilian governments and disturbed civil-military and continuous political instability. Three attempts at an effective democratic transition of power in the past produced an assassination, a military coup and an imposition of martial law. However, the 2013 General Election witnessed the first ever democratic transfer of power in the country’s political history. The elections were marred by violence but that did not stop the citizens from voting in large numbers and recording one of the highest voter turnout rates in Pakistan’s election history.

These elections also witnessed the emergence of social media, including Twitter, as a tool of election campaign and electoral mobilization (Masood 2013). For the first time in Pakistan’s politics, social media played an active role, partly because violent attacks on political rallies in the past forced political parties to place a greater emphasis on the internet campaigning during this election.

Pakistan’s political affairs in the past have been dominated by old style dynastic politics and though the 2013 General Election result signaled a victory of sorts of the same it also saw a change. The social media campaigning combined with a vastly improved voter turnout has much to do with the emergence of a (non-dynastic) third national party, Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI). PTI, a political party under the leadership of Imran Khan, a former cricket star whose appeal as an anticorruption crusader combined the party’s extensive social media campaigns helped them come out of political backwaters and establish themselves as a major force in the political reckoning of Pakistan.

Thus by exploring the usage of Twitter by Pakistani political parties during the 2013 General Election with a special emphasis on PTI, a rising political power, we will investigate the strength of Twitter as a campaign tool. We will also present an analysis of PTI’s Twitter approach and relate it to their success in the General Election with an aim to foster greater understanding of how social media campaigning in emerging democracies can contribute to success in the ballot box.

9.2 Background

9.2.1 Political Use of Twitter

With a projected social network of 500 million users in 2013, Twitter is growing as a conversational medium connecting ordinary people to celebrities, the commons to influential and citizens to governments. In recent years a number of studies have examined the use of Twitter in politics; Bruns and Burgess (2011) identified the key patterns and themes in public conversations related to elections. Kim (2011) found that Twitter was being used by citizens primarily for political information-seeking, entertainment and social utility. Larsson and Moe (2012) identified different user types based on how high-end users utilized Twitter during the 2010 Swedish election. A number of scholars have also used the networks generated within Twitter during electoral campaigning as a validated tool to predict election results (Bermingham and Smeaton 2011; Skoric et al. 2012; Sang and Bos 2012; Tumasjan et al. 2010). All these studies suggest the widespread Twitter involvement of citizens during elections.

Twitter has been widely used in recent years to support electoral campaigning (Hendricks and Kaid 2010). Scholars specifically have analyzed the use of Twitter by politicians and party organizations during election campaigns. Grusell and Nord (2011) highlight the need of Twitter examination in relation to election campaigns due to the newness of the medium. Strandberg (2013) raises the purpose of Twitter as a political mobilization tool and in doing so agrees with Norris (2001) who emphasizes the use of online tool for the purpose of engaging the citizens. A majority of such studies deal with Twitter usage in the US political environment. Metzgar and Maruggi (2009) established the facilitating role of Twitter in unfolding of the 2008 US elections. Livne et al. (2011) found significant differences in Democrats, Republicans and Tea Party candidates’ Twitter usage pattern during the 2010 midterm US elections; they suggest that conservative candidates had used the medium more effectively for campaigning. Ammann (2010) in analyzing the same data found that most tweeting by Senate candidates was informational and had no correlation to voter turnout.

A spike in Twitter research in the US context happened last year when we witnessed the ‘most tweeted’ political event in history, the 2012 US presidential elections. Studies (Conway et al. 2013; Hong and Nadler 2011) measuring the potential impact of Twitter on 2012 US presidential elections found that while Twitter expands possible modes of election campaigning, high levels of Twitter usage by election candidates did not result in their greater popularity or greater level of public attention they received online. Christensen (2013) went beyond the two-party constructs of most other studies and built a broader framework identifying Twitter usage by minority party or ‘third party’ presidential candidates during election. He found that third parties were more frequent in discussing marginal issues and their tweets were a useful indicator of the topics and issues important to minorities within the US political system.

Zhang et al. (2013) investigated the impact of different types of social media tools on voters’ attitudes and behavior during the 2012 U.S. presidential campaign. Based on their findings, they suggest that political parties can utilize the political activism fostered by social media tools like Twitter to empower and mobilize their supporter.

In other parts of the world, Bruns and Highfield (2013) tracked specific interactions between Australian politicians and the public during 2012 election in the Australian state of Queensland and found different approaches adopted by specific candidates and party organizations during the state elections. Graham et al. (2013) analyzed tweets by the candidates in the 2010 UK General Election and found that some candidates specifically used Twitter as a tool for mobilization and relationship formation with the citizens, but Aragón et al. (2013) suggest most parties usually tend to use Twitter just as a one-way flow communication tool. Vergeer et al. (2013) studied the micro blogging during the 2009 European parliament elections in the Netherlands and found low rate of Twitter usage as a campaigning tool. Vaccari and Valeriani (2013) analyzed the 2013 Italian general election and noted that the average followers of even the most followed politicians were inactive and not well-followed; very tiny minorities accounting for the vast majority of retweets and information dissemination.

9.2.2 The Case of the 2013 Pakistan General Election

Pakistan is a federal parliamentary democratic where at the national level, citizens above the age of 18 elect a bicameral legislature, the Parliament of Pakistan, which comprises of a directly elected National Assembly (lower house of the Parliament) and Senate (upper house of the Parliament), whose members are chosen by elected provincial legislators. On 11th May 2013, Pakistan elected the members of its 14th National Assembly. This was an important landmark in Pakistan’s political history, because for the first time the country witnessed a civilian transfer of power after the successful completion of a 5 year term by a democratically elected government. It suggested that Pakistan had finally overcome the clutches of the military dictatorship which overshadowed more than half its 66-year history.

Since its independence, Pakistan has seen epic socio-economic changes; but the politics in the country has been characterized by the dominance of old political parties who continue to engage in dynastic ‘family’ politics to keep their vote bank intact. Pakistani politics over the years has been dominated by Bhuttos and Zardari of Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and Sharifs of Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) with support from secondary parties such as Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM), Awami National Party (ANP) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI). The stability of the government and the organization of parliamentary elections is challenged and threatened by the domestic militant and separatist groups. The umbrella group of Pakistan Taliban, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) urged the public to boycott the 2013 general elections and warned the candidates of political parties’ such as PPP, MQM and ANP. Despite the unprecedented level of violence during the campaign, the 2013 General Election in 272 constituencies across four provinces of Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Punjab and Sindh along with Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and Federal Captial of Islamabad saw a record voter turnout of over 60 %, a marked improvement over the 44 % turnout during the 2008 elections.

The elections saw the return to power of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, once a political exile deposed by the military. Notably, the elections marked the prominent rise of the ‘unknown factor’ Imran Khan and his non-dynastic centrist party PTI. Throughout the election campaign PTI spelled out a vision of transparent government in a modern Islamic republic focusing on the power of the youth in Pakistan. Also as outlined from their policies PTI appealed for a true democracy involving active participation of the people in elections—a call to vote and constantly criticized the US drone attacks in tribal areas of Pakistan demanding for strong protests by political parties. PTI last won even a single seat in the national assembly in the 2000 General Elections; however, the 2013 elections saw the party emerging as the third most successful national party securing second highest number of votes, winning a major province, KPK, and also winning key seats in three provincial capitals. Building on his surging popularity as a nationally revered cricketing hero, Imran Khan won three out of four seats he contested for.

As of this article, social media usage is a rising trend in Pakistan, with 8 million Facebook users and 3 million Twitter users. As a result, the 2013 elections in Pakistan was also the first ‘social media’ election (McKenzie 2013) when the well-known, dynastic political parties such as PMLN, PPP and MQM as well as the challenger, PTI, turned to Facebook and Twitter to promote and connect with citizens before and during elections. This move to social media platforms was motivated not only by the aim to connect to wider audiences and optimize party visibility, but also as a safeguard to deter acts of violence. Violent attacks on political rallies are a common occurrence in election campaigns in Pakistan, and social media helped as a convenient and safe campaign platform for parties to limit holding political events in sensitive areas (McKenzie 2013).

9.3 Research Questions

A well-crafted social media campaign hugely led by Twitter has become a norm in the elections of most modern democratic societies which have high Internet and social media penetration; but what role Twitter can play in the general election of a society like Pakistan, with over 80 million voters and less than ten percent Internet penetration? This study is a step towards answering this question, with the aim to characterize the Twitter campaign strategy of the top four political parties in Pakistan during the 2013 General Election, with a special emphasis on the online campaign strategies of PTI. We posit the following research questions:

-

RQ1: Which political party was most frequently using Twitter during the elections in Pakistan?

-

RQ2: To what extent and with whom were the political parties interacting on Twitter?

-

RQ3: How was the interaction (a) between parties and (b) within parties and their sub-organizations on Twitter?

-

RQ4: What functions did the tweets by these political parties serve?

-

RQ5: What were the key societal and political issues discussed by these parties on Twitter?

-

RQ6: How did PTI’s usage of Twitter differ from that of other political parties and how did this relate to their success in the national election?

-

RQ7: What is the relationship between PTI’s provincial success and the increase in voter turnout?

9.4 Methodology

9.4.1 Data Collection

The present analysis involved two stages of data collection. The first stage of analysis was conducted on an archive of tweets posted from midnight on 10th April, 2013 (Pakistan Standard Time) to midnight on 14th May, 2013. We started to collect the data from 10th April, 2013 in order to collect data for 1 month period before the general elections which was scheduled for 11th May, 2013. In the process, we collected a total of 10,140 tweets posted by the top four political parties (PMLN, PPP, PTI and MQM) and their leaders. The tweets were downloaded in tab-delimited text format from Topsy (http://www.topsy.com/), an archive of the public Twitter stream. For this time period, we downloaded 10,140 “significant” tweets, i.e., tweets containing links or retweets. Every tweet included information about the tweet’s text, its timestamp, username, type of tweet (tweet, link, image or video), hits, trackbacks, embedded links and mentions.

For the second part of our analysis we collected the publically available statistical data related to Pakistan General Election 2013 provided by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) at their official website www.ecp.gov.pk.

We focused on Twitter data only, because we anticipated that a telecom-Twitter tie-up in Pakistan, allowing free Twitter posts by mobile subscribers, gave Twitter wider outreach and more accessibility than other social networks such as Facebook. We considered only English language tweets and filtered out tweets in other languages such as Urdu, which accounted for 158 or 1.5 % of the total tweets collected. Clearly this is a small number compared to the total number of English language tweets, so we anticipate that discarding them will not impact our findings.

9.4.2 Coding Categories

A manual content analysis was employed as the principal mechanism for examination where an individual tweet was the unit of analysis. The first stage of coding scheme focused on the type of tweet. In Twitter terminology, a tweet is a micro-blog post. Besides posting original content in a normal post, a tweet could also be a mention of a different Twitter user, a reply to a tweet by another Twitter user, a retweet or reposting of a tweet posted by someone else. In the context of Twitter political campaigning, the following four tweet types were established (Table 9.1):

Once the types of tweet were established we moved to the second stage of coding scheme where @ replies were consequently coded to understand with whom were the parties interacting through their tweets. For assurance of classification of a user’s profile the coders first checked the user’s profile and then if needed clicked on the user’s profile details to find more information and then classify the user accordingly into respective category. The categories are mentioned in Table 9.2.

At the final stage of the coding scheme, partly based on approach tested previously in Twitter research (Graham et al. 2013) the tweets were coded for their function. In cases where the tweet could fall into two or more functional categories, coders were asked to pay attention to the dominant functional category. These categories are presented in Table 9.3. A team of four coders were employed to code the tweets for the above mentioned categories. The inter-coder reliability was tested by randomly selecting 25 % of the coded tweets by each coder and the reliability was found to be satisfactory.

9.4.3 Word Cloud and N-Gram Phrase Extractor

For a preliminary frequency analysis of words in text, we generated word clouds from the tweet streams of individual parties. Word clouds are a method of visualizing text frequencies, in which the more frequently appearing words in a source text are rendered in bigger sizes to give them greater prominence in display. We used an online word cloud generator hosted at Wordle.net; the developer describes that this tool is useful to get the “portrait” of interests mentioned in the text (Feinberg 2010). We anticipated that the visualization would give us a convenient way to compare the main concerns and interests of the political party Twitter accounts.

Similarly, we compared the frequently recurring phrases in the tweet streams by using the N-Gram Phrase extractor hosted at the website, Compleat Lexical Tutor (http://www.lextutor.ca/tuples/eng/). N-grams refer to contiguous phrases of “N” length which are generated from provided text. The N-Gram Phrase extractor tool is suitable for analyzing really short texts, such as those in a tweet, and extracting recurring phrases and displaying the output in varying spans of co-text (usually 17–20 words) with the phrases centered and listed in alphabetical order. Information about how many times a phrase, or a “lexical bundle” occurs in the text is reported to the left of the page with phrases listed alphabetically. Since this program reports only those lexical bundles that recur in the text or file submitted by the user, it provides a good way to examine the extent and type of lexical bundles that their political parties are applying in their writings. To improve the counting of repetitious phrases, the N-Gram Extractor notices and discounts up to three intervening words so that phrases like “a car” and “a big car” are counted as repeated units. Furthermore, by reducing all words to their family headwords, the software is able to identify and collate phrases such as “I go home” and “He goes home”. Accordingly, we set the program to extract and count all phrases ranging from two to four words in length and to consider intervening words and family headwords. We anticipated that identifying and analyzing lexical bundles would reveal a lot more about the central issues or claims which political parties were iteratively targeting in their Twitter campaign.

9.4.4 Social Network Analysis

To better understand the characteristics of the online network community formed by the Pakistani political parties and their leaders on Twitter, we conducted a social network analysis. We used Gephi 0.8, a tool developed by Bastian et al. (2009), to analyze formed network and visualize it. For social network graph rendering, we wanted to identify how the Twitter accounts were connected to one another, which is why we chose to visualize the network with the Harel-Koren Fast Multiscale layout.

9.5 Findings

Our findings are presented in two parts. First we analyzed the collected data from Twitter API and the respective results are presented as Tweet Analysis in Sect. 5.1 and secondly the analysis for the election results data gathered from ECP’s website are presented as Election Analysis in Sect. 5.2.

9.5.1 Tweet Analysis

Table 9.4 provides the descriptive statistics for the parties and their Twitter accounts. Evidently, PTI and its leader, Imran Khan, have the greatest number of followers as compared to other parties and their respective leaders. The Table also provides the Klout scores for the individual Twitter accounts. Klout measures users’ online social influence based on how others engage with their content. Although the algorithm behind Klout, which is based on more than 25 variables, has not been published, it is based on a user’s interaction with others in their social networks and the networks’ reaction to the user’s activity. The Klout scores for the Twitter accounts of PTI and Imran Khan were higher than those of other parties and politicians.

The answer to the first research question, RQ1, required a simple frequency analysis of the tweets posted by the top four political parties. Figure 9.1 provides a timeline illustrating the distribution of tweets throughout the observed period of 10th April to 14th May 2013 for PPP, MQM, PMLN and PTI.

The trendline for each party is characterized by several small spikes in frequency, leading up to the highest spike on Election Day itself, on 11th May. The smaller spikes before the Election Day likely correspond to offline events including major political campaigns. From the Fig. 9.1, PTI emerges as the most active party on Twitter during the campaign period and the day of election. There was an exception on 18th April when PMLN announced its candidates list.

Figure 9.2 shows trendlines for only PTI’s tweets, specific to the five provinces of Baluchistan, KPK, Punjab, Sindh and FATA/Federal Capital. Tweets specific to KPK were found to be consistently high in this analysis.

To answer the second research question, RQ2, we identified the types of tweets and their percentage distribution for each of the four political parties and the findings are provided in Table 9.5. We found that political parties were using Twitter quite differently from each other. PTI was again the leader in interacting with users (21 % of their tweets were replies). They were second to PPP in mentioning their party leader in their tweets. They may have been highlighting their party leader, Imran Khan, because his popularity and fan-following—as of this study, he is the most followed Twitter user in Pakistan. On the other hand, PMLN and MQM used Twitter to moderately interact with their followers.

It was imperative to understand with whom were these parties interacting on Twitter. Figure 9.3 reveals the results as the two most frequent parties on Twitter, PMLN and PTI were largely interacting with the public while PPP and MQM interacted with politicians. It is noteworthy that PTI were once again ahead of other parties in interacting not only with the public but also the media. This can be explained by the fact that PTI is the only non-historical party in Pakistan politics and is more in need of traditional media presence as well.

To answer RQ3, it was necessary to identify the prevalence, if any, of discussions between and within party Twitter accounts. We followed the approach adopted by most scholars (Grant et al. 2010) and constructed a network based on instances of conversations (at least one tweet in either direction) involving the Twitter accounts of one or more political parties or their leaders or their regional branch. To render the social network, the Harel-Koren Fast Multiscale layout was used to cluster tightly connected users to one another. Clusters appear to exist in the network graph but they are largely exclusive and not much interaction between parties was visible. However, when we focussed only on PTI tweets we did find interaction between PTI’s official account and its leader (@imrankhanpti) and other sub-organisations (@ptikpkofficial, @ptipnjbofficial) as visible in Fig. 9.4. We tested the PTI network for actual clustering coefficient (C) and average path length (L). The results showed L = 2.937, C = 0.891 signifying a small world network. This reveals that PTI used the medium for unmediated connection amongst their sub-divisions and leader, Imran Khan.

In preliminary analysis for RQ 4–5 to identify what Pakistani political parties and politicians were tweeting about, we first generated word clouds from their parties’ tweets. Word clouds are a method of visualizing text frequencies, in which the more frequently appearing words in a source text are rendered in bigger sizes to give them greater prominence in display. Figures 9.5, 9.6, 9.7, 9.8 present word clouds of Pakistani political parties’ tweets and provide an emblematic illustration of the topics discussed in their tweets.

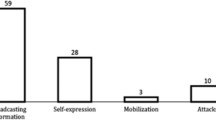

A deeper content analysis was then conducted to identify the functions of tweets posted by each of the political parties. Figure 9.9 reveals that the top three parties PMLN, PPP and PTI predominantly used Twitter for posting updates about their campaign and also as a platform for campaign promotion. It shows that PTI were ahead of other parties in campaign updates via Twitter but used it less as a criticism tool to criticize other parties and politicians, while MQM used the platform more for criticism than any other function. The most significant finding was the use of Twitter to call out the voters to exercise their right to vote. While most other parties rarely used Twitter to urge citizens to vote, approximately every one out of ten PTI tweets urged the users to vote.

RQ5 investigates the other key issues of development being discussed by political parties. First, we used N-Gram Phrase Extractor to extract the most frequent terms and keywords used in the subset of tweets from each party. From the overall results, we limited our analysis on the top 25 two-word and three-word strings as these accounted for maximum repeated usage and would reveal the importance of issues in party discussions. We then removed the terms related to campaign updates and promotions (e.g.; “Campaign coverage by”, “from NA-128”, “today polling station”) to focus only on issues (if any) discussed by the parties. We then manually clubbed the frequently occurring words into common themes. The top discussed themes (issues) and the common frequent words (two-string and three-string) are listed in Table 9.6.

9.5.2 Election Analysis: Seats and Popularity

Considering the actual results of the 2013 Pakistan General Elections, Table 9.4 shows that PMLN was the most successful (126 National Assembly seats) and the most popular party (14.8 million votes). PTI was third on the number of seats won (28 seats) and the second most popular party in Pakistan with nearly 7.6 million votes.

Table 9.7 shows that other than the leader PMLN, PTI also gathered more votes per candidate (32,601) as compared to other parties. In the detailed party performance to understand the voting patterns across provinces, it is evident that each province favored a particular party. PMLN won the majority at the national level—but their performance was largely based on the success in Punjab. PPP were largely successful in Sindh while MQM won all their seats from Sindh. PTI dominated KPK, but it also won some seats from Punjab, Sindh and FATA/Fed Cap.

9.5.3 Election Analysis: Voter Turnout and Increase in Votes Polled

The Election Commission of Pakistan declared that the overall voter turnout in the Pakistan general elections 2013 was 55.02 %—an approximately 11 % increase since the last general elections in 2008. We compared the province-wise voter turnout for 2008 and 2013 to check whether this had a role to play in PTI’s success.

Keeping the voter turnout for the 2008 general elections as base (100 %) we plotted the turnout for the 2013 general elections to identify the increase in number of votes polled per province. The results are displayed in Fig. 9.10. There was a jump of 29.68 % in the number of votes polled nationally in 2013 compared to the polled votes in 2008. Notably, the most prominent increase in votes polled was in the province of KPK (53.12 % increase). This was also where PTI achieved the most success and won 17 National Assembly seats. KPK was followed by FATA/Fed Capital where the increase was 40.50 %. Also PTI was the second most successful party in Punjab, FATA/Fed Capital which recorded a significant increase in votes (34.1 and 40.5 %). The two provinces which faired below the national average of increase in votes, Sindh (13.1 %) and Baluchistan (−4.9 %) were the provinces where PTI did not fare as well, by winning just one National Assembly seat in Sindh and not recording victory in Baluchistan.

9.5.4 Election Analysis: Voter Age Group

2013 was deemed as Pakistan’s first ‘youth election’. When we analyzed the data for the voter age group, our results established the same. On the national level, about 35 % of the voters were under the age of 30 years. 20 % of the total comprised youth in the age group of 18 to 25 years (Fig. 9.11). At the province level, we found the majority of the youngest eligible voter population in the province of KPK, with approximately 24 % of the population between the age group of 18 to 25 years. This was a major difference when compared to other significant provinces of Punjab and Baluchistan.

9.6 Discussion

This study focused on the usage of Twitter in the general elections of a democratic society which is not only characterized by low social media penetration but faces threats of ethnic and political violence in its dynastic political environment. The question posed here was if Twitter as a campaigning tool can make a difference in the general elections of such a society?

Our findings revealed that a new and upcoming political party, PTI, used the medium in an effective manner and were the most benefitted by their social media participation, which helped them to win nearly 30 seats in the National Assembly in 2013 elections, as compared to none in the previous election. PTI applied a combination of strategic online and offline campaigning led by the youth, which emphasized a call for action against corruption in the country. Imran Khan led extensive on the road campaigns in Punjab, a province where PMLN historically holds a strong hand. On 26th April, Imran Khan attended 32 public gathering within six hours to cover large grounds and all the updates related to campaigns were regularly updated on Twitter. However in Karachi, a city with a population of 20 million people that saw all the parties holding extensive public rallies, PTI stayed away and did not organize even a single campaign event during the elections. PTI strategically and solely focused on online activities in Karachi as the city has disproportionally high percentage of youths within its population who are actively connected to the Internet. This proved successful as the party became the second largest party in the city after winning an important national assembly seat and three provincial assembly seats. Thus what we observe is Twitter presenting itself as a direct force in election campaign in some provinces while acting as an additional facilitator in others.

Overall, PTI evolved as the most dominant party on Twitter and this is in accordance with previous arguments too (Christensen 2013; Lassen and Brown 2011) which suggest that minority parties are usually most active online after being drawn to the medium for lack of television and mainstream media exposure. These parties (PTI in the case of Pakistan) face incredible challenge in reaching out to the public, and thus voters, partially due to the symbiotic relationship between the traditional mass media channels and the leading political parties.

If we compare PTI’s online campaign to the election studies in the US, we note that their approach seems to be inspired from Obama’s social media team in 2008, who also favorably exploited Twitter to their advantage and in a way set a trend of using the tool for election campaigning. PTI was most active in uploading a large selection of campaign photos and videos and providing real time updates of Imran Khan’s campaign activities from the ground. This is reflected in the trendline for PTI in Fig. 9.1, when we see a mini peak for PTI on the 24th April, the day when Imran Khan held press conferences discussing a more credible polling system. Similarly we see another mini peak on 8th May just before the Election Day, as this was the day when Imran Khan was injured after falling from a makeshift stage during a campaign rally in Lahore. The correlation of online and offline activity concurs with other Twitter-politics research (Bruns and Highfield 2013; Larsson and Moe 2012) which shows that the online social media activity peaks in relation with major offline events, including campaigns and wide political events.

The political social media campaign of Obama and Khan are also similar in the way they emulate the personality politics paradigm. Political campaigns emphasize the personalities of their candidates to capture the voters’ attention, exemplified in Obama’s campaign and subsequent triumph in the 2008 and 2012 US Presidential Election (Wayne 2011). The popularity of political actors also impinges on personal relationships in numerous ways, often with significant consequences. Imran Khan is the most followed Twitter user in Pakistan and this speaks volumes about his popularity, at least in the online sphere. PTI’s political campaign on Twitter was built around the Khan persona, being moderately frequent but not overwhelming in direct mentions of their leader in their tweets. A similar approach was followed by PPP whose former leader and late Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, the first woman prime minister of Pakistan, was assassinated during a campaign rally in 2007.

Political parties use Twitter primarily as a tool for interaction. Our analysis found that almost every party focused on a different issue based on their party agenda. PMLN raised concerns about the energy crisis within the country and criticized PPP due to frequent electricity breakdowns (sometime up to 18 h a day at the peak of summer. PPP built on the agenda of its former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and concentrated on their work and importance of socio-economic development and empowerment of women. MQM were critical of the bomb blasts by Taliban near its office in Karachi. PTI’s tweets focused on issues of drone attacks. However, quite different to other political parties, PTI were also extremely active in promoting voting behavior and focusing on youth. Their focus on capturing the youth’s attention is a tactical move considering the overwhelming numbers of young voters in Pakistan; a majority of them were likely connected to the online world and helped to turn the party’s luck. Out of an electoral list of 83 million voters, 47 % of the voters were under the age of 35 and 30 % under 30 years. According to the National Database Registration (NADRA) 30 million voters were newly listed in the electoral rolls, out of which a high proportion turned 18 years only in the last 3 years. Hence, PTI maximized the medium to connect to youth and discuss their issues.

Our finding revealed that PTI maintained a strong online interactive presence at two levels: internal and external. Primarily, the party was active in connecting between the main account and its sub-organization accounts with a strong focus on interaction with KPK and also its chairman, Imran Khan. Where most political parties had one or maximum two Twitter accounts to connect with the public and others, PTI had one main account (@ptiofficial), four regional accounts (@ptipnjbofficial, @ptikpkofficial, @ptibaluchistan and @ptisindhoffice), one account dedicated to television program (@ptitvprgos) updates along with Imran Khan’s account (@imrankhanpti). With these accounts, PTI created a small world network consistently engaging citizens and others within and outside of their network.

At the secondary level, PTI interacted with the public; in fact, they were the most active in interacting with the electorate and promoting the character of Imran Khan as a potential prime minister. Interaction over Titter bypassed traditional media “gatekeepers” such as newspaper or television journalists, which are responsible for filtering, editing and interpreting a party’s messages to the citizens.

9.7 Conclusion

The 2012 General Election was one of the most successful elections in Pakistan’s political history. Although we cannot establish prime causal factors, but our analysis did find PTI to be ahead of all other parties in calling out the citizens to exercise their voting rights. This action reflected their election manifesto where they had criticized the low voter turnout figures and urged the citizens to contribute toward the democracy in Pakistan. Their offline action of pushing the ECP to grant voting rights to overseas Pakistanis (present day Pakistani constitution does not enable Pakistanis settled abroad to vote in general elections) supplemented their online action and political intention of bringing Pakistan closer to a true democracy.

PTI’s success at the provincial level and more specifically in KPK reflects the way they successfully wielded Twitter as a political campaign tool. Probably the greatest contributors to their win were the high percentage of voting population under the age of 25 and the overall increase in number of votes. These factors combined with PTI’s focus on KPK through their Twitter activity and on the road campaigns resulted in a strong success in the region.

To sum up, our findings indicate that Twitter can play a significant role even in a fragile societal and political environment like Pakistan. PTI’s offline strategies and their online involvement on Twitter signifies that the medium can be robustly used to involve more people in a democratic process, especially the youth, by providing them with campaign updates, interacting with them and mobilizing them to vote.

Notes

An earlier version of this study was presented at the 47th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Ahmed and Skoric 2014).

See [Ahmed, S., & Skoric, M. M. (2014, January). My name is Khan: The use of Twitter in the campaign for 2013 Pakistan General Election. Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 2242–2251). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society]

References

Ahmed, S., & Skoric, M. M. (Jan 2014). My name is Khan: The use of Twitter in the campaign for 2013 Pakistan General Election. Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 2242–2251). IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC.

Ammann, S. (2010). A political campaign message in 140 characters or less: The use of Twitter by US Senate candidates in 2010. Available at SSRN 1725477.

Aragón, P., Kappler, K. E., Kaltenbrunner, A., Laniado, D., & Volkovich, Y. (2013). Communication dynamics in twitter during political campaigns: The case of the 2011 Spanish national election. Policy & Internet, 5(2), 183–206.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (May 2009). Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM) (pp. 361–362).

Bermingham, A., & Smeaton, A. (2011). On using twitter to monitor political sentiment and predict election results. Proceeding of IJCNLP conference, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011). The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. European Consortium for Political Research conference, 25–27 August 2011. Reykjavík.

Bruns, A., & Highfield, T. (2013). Political networks on twitter: Tweeting the Queensland state election. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 667–691.

Christensen, C. (2013). Wave-riding and hashtag-jumping: Twitter, minority ‘third parties’ and the 2012 US elections. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 646–666.

Conway, B. A., Kenski, K., & Wang, D. (2013). Twitter use by presidential primary candidates during the 2012 campaign. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(11), 1596–1610.

Feinberg, J. (2010). Wordle. In J. Steele & N. Iliinsky (Eds.), Beautiful Vizualization: Looking a data through eyes of experts (pp. 37–58). O’Reilly Media: CA.

Graham, T., Broersma, M., Hazelhoff, K., & van’t Haar, G. (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters: The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 692–716.

Grant, W. J.,Moon, B., & Busby Grant, J. (2010). Digital dialogue? Australian politicians’ use of the social network tool Twitter. Australian Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 579–604.

Grusell, M., & Nord, L. W. (May 2011). Small talk, huge impact? The Role of Twitter in the National Election Campaign in Sweden in 2010. In IAMCR 2011-Istanbul.

Harfoush, R. (2009). Yes we did! An inside look at how social media built the Obama brand. Berkeley: New Riders.

Hendricks, J. A., & Kaid, L. L. (2010). Techno politics in presidential campaigning. New York: Routledge.

Hong, S., & Nadler, D. (June 2011). Does the early bird move the polls?: The use of the social media tool ‘Twitter’ by US politicians and its impact on public opinion. Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference: Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times (pp. 182–186). ACM.

Kim, D. (2011). Tweeting politics: Examining the motivations for Twitter use and the impact on political participation. 61st Annual Conference of the International Communication Association.

Larsson, A. O., & Moe, H. (2012). Studying political microblogging: Twitter users in the 2010 Swedish election campaign. New Media & Society, 14(5), 729–747.

Lassen, D. S., & Brown, A. R. (2011). Twitter the electoral connection? Social Science Computer Review, 29(4), 419–436.

Livne, A., Simmons, M. P., Adar, E., & Adamic, L. A. (July 2011). The party is over here: Structure and content in the 2010 election. Proceedings of the Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Masood, S. (13 May 2013) Pakistani leader moves quickly to form government. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/14/world/asia/pakistan-election-developments.html?_r=1 & . Accessed 11 June 2013.

McKenzie, J. (8 May 2013). Pakistanis take refuge in social media campaigning before election. Techpresident. http://techpresident.com/news/wegov/23853/pakistanis-take-refuge-social-media-campaigning-election. Accessed 7 June 2013.

Metzgar, E., & Maruggi, A. (2009). Social media and the 2008 US presidential election. Journal of New Communications Research, 4(1), 141–165.

Norris, P. (2001). Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Neill, B. (2010). New Zealand politicians’ use of social media applications: A political social capital perspective. http://130.217.226.8/handle/10652/1450. Accessed 10 June 2013.

Posetti, J. (2011). The Spill Effect: Twitter Hashtag Upends Australian Political Journalism Mediashift (PBS). http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2010/03/the-spill-effect-twitter-hashtag-upends-australian-political-journalism061. Accessed 13 June 2013.

Sang, E. T. K., & Bos, J. (April 2012). Predicting the 2011 Dutch senate election results with twitter. Proceedings of the Workshop on Semantic Analysis in Social Media (pp. 53–60). Association for Computational Linguistics.

Skoric, M., Poor, N., Achananuparp, P., Lim, E. P., & Jiang, J. (Jan 2012). Tweets and votes: A study of the 2011 Singapore general election. 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Science (HICSS) (pp. 2583–2591). IEEE.

Strandberg, K. (2013). A social media revolution or just a case of history repeating itself? The use of social media in the 2011 Finnish parliamentary elections. New Media & Society, 15(8), 1329–1347.

Tumasjan, A., Sprenger, T. O., Sandner, P. G., & Welpe, I. M. (2010). Predicting elections with Twitter: What 140 characters reveal about political sentiment. ICWSM, 10, 178–185.

Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2013). Follow the leader! Direct and indirect flows of political communication during the 2013 general election campaign. New Media & Society, 1461444813511038.

Vergeer, M., Hermans, L., & Sams, S. (2013). Online social networks and micro-blogging in political campaigning. The exploration of a new campaign tool and a new campaign style. Party Politics, 19(3), 477–501.

Wayne, S. J. (2011). Personality and politics: Obama for and against himself. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Zhang, W., Seltzer, T., & Bichard, S. L. (2013). Two sides of the coin assessing the influence of social network site use during the 2012 US presidential campaign. Social Science Computer Review, 31(5), 542–551.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kokil Jaidka for her programming skills which were valuable in data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ahmed, S., Skoric, M. (2015). Twitter and 2013 Pakistan General Election: The Case of David 2.0 Against Goliaths. In: Boughzala, I., Janssen, M., Assar, S. (eds) Case Studies in e-Government 2.0. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08081-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08081-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-08080-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-08081-9

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)