Abstract

In this chapter, the results of a research synthesis of the effects on school size on various outcome variables are presented. The present review built on an earlier “quick scan” on the impact of secondary school size on achievement, social cohesion, school safety, and involvement conducted for the Dutch Ministry of Education and Sciences in 2008 (Hendriks et al. 2008). It focuses on a broader set of outcome variables, and includes studies that investigated the effects of school size in primary education as well. Studies that provided information about economies of school size were included as well.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- School Size

- Vote-counting Procedure

- Extra-curricular Participation

- National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS)

- Small Schools

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

In this chapter, the results of a research synthesis of the effects on school size on various outcome variables are presented. The present review built on an earlier “quick scan” on the impact of secondary school size on achievement, social cohesion, school safety, and involvement conducted for the Dutch Ministry of Education and Sciences in 2008 (Hendriks et al. 2008). It focuses on a broader set of outcome variables, and includes studies that investigated the effects of school size in primary education as well. Studies that provided information about economies of school size were included as well.

The research synthesis seeks answers on the following research questions:

-

(1)

What is the impact of school size on various cognitive and noncognitive outcomes?

-

(2)

What is the “state of the art” of the empirical research on economies of size?

To answer the first question the impact of school size of variety of student, teacher, parents’, and school organizational outcome variables was investigated. A distinction is made between outcome variables, i.e., cognitive and noncognitive outcome variables, and school organization variables. Cognitive outcomes refer to student achievement. The noncognitive outcome variables included in the review relate both to students’ (attitudes toward school and learning, engagement, attendance, truancy, and drop-out) and teachers outcomes (satisfaction, commitment, and efficacy). School organization variables relate to safety, to involvement of students, teachers and parents, as well as to other aspects of the internal organization of the school, including classroom practices (i.e., aspects of teaching and learning). In the review school organization variables are seen both as a desirable end in itself, but also as intermediate variables conducive to high academic performance and positive student and teacher attitudes. To answer the second question, costs was included as a dependent variable in the review.

In the research synthesis we were not able to apply a quantitative meta-analysis in which effect sizes are combined statistically. One reason was many empirical studies did not provide sufficient information to permit the calculation of an effect size estimate. What is more, in many of the studies the relationship of school size and a dependent variable is not always modeled as a linear relationship. Instead a log-linear or quadratic relationship is examined or different categories of school size are compared, of which the number and distribution of sizes over categories varies between studies.

Therefore in this research synthesis, we used the so-called vote count technique, which basically consists of counting the number of positive and negative statistically significant and nonsignificant associations. This technique could be seen as a rather primitive form of meta-analysis,Footnote 1 and has many limitations, as will be documented in more detail when presenting the analyses. In this chapter, the results of the vote counts with a narrative review providing more in-depth information on a great number of the studies included in the review.

3.1 Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A computer-assisted literature search procedure was conducted to find empirical studies that investigated the impact of school size on a wide array of student outcomes (such as achievement, cohesion, safety, involvement, participation, attendance, drop-out, and costs). Literature searches of the electronic databases Web of science (www.isiknowledge.com), Scopus (www.scopus.com), ERIC, Psycinfo (provided through Ebscohost), and Picarta were conducted to identify eligible studies. Search terms included key terms used in the meta-analyses by Hendriks et al. (2008), i.e., (a) “school size,” “small* schools,” “large* schools” (b) effectiveness, achievement (c) cohesion, peer*, climate, community*, “peer relationship,” “student teacher relationship” (d) safe*, violence, security (e) influence*, involvement, participation (f) truancy, “drop out,” attendance, and (g) costs. In the search, the key terms of the first group were combined with the key terms of each other group separately. We used the limiters publication date January 1990–October 2012 and peer reviewed (ERIC only) to restrict our search.

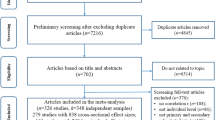

The initial search in the databases yielded 1,984 references and resulted in 875 unique studies after removing duplicate publications. The titles and abstracts of these publications were screened to determine whether the study met the following criteria:

The study had to include a variable measuring individual school size. Studies investigating schools-within-schools or studies examining size at the school district level were not included in the review. Studies were also excluded if size was measured as grade or cohort enrollment or the number of teachers in the school.

The dependent variable of the study had to be one or more of: (1) student attainment and progress, (2) student behavior and attitudes, (3) teacher behavior and attitudes, (4) school organizational practices and teaching and learning, and (5) economic costs

The study had to focus on primary or secondary education (for students aged 6–18). Studies that focused on preschool, kindergarten, or on postsecondary education were excluded.

The study had to be conducted in mainstream education. Studies containing specific samples of students in regular schools (such as students with learning, physical, emotional, or behavioral disabilities) or studies conducted in schools for special education were excluded from the meta-analysis.

The study is published or reported no earlier than January 1990 and before December 2012.

The study had to be written in English, German, or Dutch.

The study had to have estimated in some way the relationship between school size and one or more of the outcome variables. Study had to report original data and outcomes. Existing reviews of the literature were excluded from the review.

When cognitive achievement was the outcome variable studies had to control for a measure of students’ background, such as prior cognitive achievement and/or socioeconomic status (SES).

After this first selection, 314 studies left for the full text review phase. In addition recent reviews on school size (i.e., Andrews et al. 2002; Newman et al. 2006; Hendriks et al. 2008; Leithwood and Jantzi 2009) as well as references from the literature review sections from the obtained publication were examined to find additional publications. A cut-off date for obtaining publications was set at 31 December 2012.

The full text review phase resulted in 84 publications covering the period 1990–2012 admitted to the review and fully coded in the coding phase. The data were extracted by one of two reviewers and confirmatory data extraction was carried out by a second reviewer.

3.2 Coding Procedure

Lipsey and Wilson (2001) define two levels at which the data of the study should be coded: the study level and the level of an effect size estimate. The authors define a study as “a set of data collected under a single research plan from a designated sample of respondents” (Lipsey and Wilson, p. 76). A study may contain different samples, when the same research is conducted on different samples of participants (e.g., when students are sampled in different grades, cohorts of students or students in different stages of schooling -primary or secondary-), or when students are sampled in different countries. An estimate is an effect size, calculated for a quantitative relationship between an independent and dependent variable. As a study may include different measurements of the independent variable (school size), as well as different measures of the dependent variable (such as e.g., different outcome measures (achievement, engagement, drop-out), different achievement tests covering different domains of subject matter (e.g., language or math), measurement as different point is time (learning gain after 2- and 4 years), a study may yield many effect sizes, each estimate different from the others with regard to some of its details.

The studies selected between 1990 and 2012 were coded by the researchers applying the same coding procedure as used by Scheerens et al. (2007). The coding form included five different sections: report and study identification, characteristics of the independent (school size) variable(s) measured, sample characteristics, study characteristics, and school size effects (effect sizes).

The report and study identification section recorded the author(s), the title and the year of the publication.

The section with characteristics of the explanatory variable(s) measured coded the operational definition of the size variable(s) used in the study (In all studies referring to a measure of total number of students attending a school) as well as the way in which the relationship between size and outcomes was modeled in the study: either linear or transformed to its logarithm (size measured as a continuous variable), quadratic (estimating both linear and quadratic coefficients), or comparing different size categories.

The sample characteristics section recorded the study setting and participants. For study setting the country or countries in which the study was conducted were corded. With regard to participants, the stage of schooling (primary or secondary level) the sample referred to was coded as well as the grade or age level(s) of the students the sample focused on. The number of schools, classes, and students included in the sample were recorded as well.

The study characteristics section coded the research design chosen, the type of instruments employed to measure the time variable(s), the statistical techniques conducted and the model specification. For the type of research design, we coded whether the study applied a quasi experimental—or experimental research design and whether or not a correlational survey design was used. With regard to the type of instruments used we coded whether a survey instrument or log was used and who the respondents were (students, teachers, principals, and/or students), and whether data were collected by means of classroom observation or video-analysis or (quasi-) experimental manipulation. The studies were further categorized according to the statistical techniques conducted to investigate the association between time and achievement. The following main categories were employed: ANOVA, Pearson correlation analysis, regression analysis, path analysis/LISREL/SEM, and multilevel analysis. We also coded whether the study accounted for covariates at the student level, i.e., if the study controlled for prior achievement, ability, and/or student social background.

Finally, the school size effects section recorded the effects sizes, either taken directly from the selected publications or calculated. The effect sizes were coded as reflecting the types of outcome variables distinguished in the review (i.e., achievement, students’ and teachers’ attitudes to school, students’, teachers’ and parents’ participation, safety, attendance, absenteeism, truancy and drop out, school organization and teaching and learning, and costs). With regard to achievement, four groups of academic subjects were distinguished in the coding: language, mathematics, science, and other subjects.

3.3 Vote Counting Procedure

As the nature of the data reported in the 84 studies and 107 samples did not permit a quantitative meta-analysis without eliminating a significant number of studies in each of the outcome domains, a vote counting procedure was applied. Vote counting permitted inclusion of those studies and samples that reported on the significance and direction of the association of school size and an outcome measure, but did not provide sufficient information to permit the calculation of an effect size estimate. Vote counting comes down to counting the number of positive significant, negative significant, and nonsignificant associations between an independent variable and a specific dependent variable of interest from a given set of studies at a specified significance level, in this case school size and different outcome measures (Bushman and Wang 2009). We used a significance level of α = 0.05. When multiple effect size estimates were reported in a study, each effect was individually included in the vote counts. Vote counting procedures were applied for each of the (groups of) dependent variables: achievement, students’ and teachers’ attitudes to school, students’, teachers’ and parents’ participation, safety, attendance, absenteeism, truancy and drop out, school organization and teaching and learning, and costs.

The vote counting procedure has been criticized on several grounds (Borenstein et al. 2009; Bushman 1994; Bushman and Wang 2009; Scheerens et al. 2005). It does not incorporate sample size into the vote. As sample sizes increase, the probability of obtaining statistically significant results increase. Next, the vote counting procedure does not allow the researcher to determine which treatment is the best in an absolute sense as it does not provide an effect size estimate. Finally, when multiple effects are reported in a study, such a study has a larger influence on the results of the vote-count procedure than a study where only one effect is reported.

As vote counting is less powerful it should not be seen as a full blown alternative to the quantitative synthesis of effect sizes, but, rather as a complementary strategy.

Table 3.1 gives an overview of the studies, samples, and estimates included in the vote counting procedures for each type of outcome variables (i.e., achievement, students’ and teachers’ attitudes to school, students’, teachers’ and parents’ participation, safety, attendance, absenteeism, truancy and drop out, school organization and teaching and learning, and costs) as well as in total.

3.4 Moderator Analysis

Moderator analyses were conducted to examine the degree to which the relationship between school size on one hand and an outcome variable on the other could be attributed to specific sample or study characteristics. Due to the low number of samples included in the review for most of the outcome variables (see Table 3.1), moderator analysis was only applied for those studies and samples that included student achievement or safety as the outcome variable, and in which the relationship between size and outcomes was modeled as a linear or log-linear function. The following types of moderator variables were used in our analyses: sample characteristics as geographical region, and the level of schooling (primary, secondary schools), and study characteristics that refer to methodological and statistical aspects, e.g., study design, model specification, whether or not covariates at the student level (SES, cognitive aptitude, prior achievement) or school level (school level SES, urbanicity) are taken into account and whether or not multilevel analysis was employed.

3.4.1 Characteristics of the Studies and Samples Included in the Review

In total, 84 studies and 107 samples were included in the review. Almost three quarter of the studies (i.e., 58 studies) originate from the United States. Seven studies were conducted in the Netherlands, four in the United Kingdom, three in Israel, two in Canada, two in Sweden, and one in each of Australia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, and Taiwan.

Eighteen studies examined effects of school size in primary education contexts, 53 studies in secondary schools, and six studies collected data in primary and secondary schools separately. In three studies, a combined sample of primary and secondary schools was used.

More detailed information about the characteristics of the samples and studies can be found in Tables A.1 and A.2.

3.5 Results

3.5.1 Academic Achievement

Evidence about the relationship between school size and academic achievement was derived from 46 studies and 64 samples (yielding in total 126 effect estimates). Of the 46 studies, 20 studies (22 samples) provided evidence about the relationship between school size and achievement in primary education. Evidence about the effects of school size in secondary education was available from 29 studies (39 samples). In five studies the data were obtained from samples that included students from both levels of schooling. The majority of studies (and samples) were conducted in the United States. The other studies originate from Canada (1 sample), Hong Kong (1 sample), The Netherlands (2 samples), and Sweden (2 samples).

Table 3.2 shows the results of the total number of negative, nonsignificant, curvilinear, and positive effects found for the associations between school size and achievement. In this table, evidence is presented for all studies in total as well as separately for the three different ways in which school size is measured in the studies: (1) school size measured as a continuous variable usually operationalized as the total number of students attending a school or different sites of a school at a given date, suggesting a linear relationship, (2) school size measured as a quadratic function, seeking evidence for a curvilinear relationship and, (3) school size measured through comparison of different categories. In these latter studies, the evidence reported could show either a linear or curvilinear relationship, or favoring a certain size category.

The results of the vote counting show that of 126 effects sizes in total, more than half of the associations (78 effects, 62 %) between school size and achievement appeared to be nonsignificant, 23 estimates (18 %) showed negative effects and 11 estimates (9 %) positive effects.

3.5.2 School Size Measured as a Continuous Variable

When school size was measured as a continuous variable, in 11 of the 46 samples (20 effects) a negative relationship between school size and achievement was reported while in 8 samples (8 effect sizes) it was found that achievement rises as school size increases (see Tables 3.2 and A3).

In 15 of the 46 samples effects were examined for more than one achievement measure (e.g. in different domains (language or math), or at different points in time), the effects reported within one sample were in the same direction, thus all effects found were either nonsignificant, positive, or negative. The only sample that reported conflicting results was the study by Fowler and Walberg (1991). In this study 13 school achievement outcome measures were regressed on 23 school characteristics. After district socioeconomic status and the percentage of students from low-income families were accounted for, school size was the next most influential and consistent factor related to outcomes. Five of the achievement measures were negatively associated with school size; the other effects were nonsignificant. According to the authors these results suggest “that smaller school districts and smaller schools, regardless of socioeconomic status …, may be more efficient at enhancing educational outcomes” (p. 189). However, other authors (Spielhofer et al. 2004) recommended caution as only school level data were used in the regression analysis.

Besides Fowler and Walberg, eight other studies (samples) also found negative associations between school size and achievement (Archibald 2006; Caldas 1993; Deller and Rudnicki 1993; Driscoll et al. 2003; Heck 1993; Lee and Smith 1995; Moe 2009; Stiefel et al. 2006). In four of these studies the effect of school size on achievement was examined at different levels of schooling (Caldas 1993; Driscoll et al. 2003; Moe 2009; Stiefel et al. 2006). In these four studies the authors all reported a (weak) negative effect for primary education while for secondary education a nonsignificant (negative or positive) effect was found. Two of the remaining studies were conducted in primary education (Archibald 2006; Deller and Rudnicki 1993) and in the study by Heck a sample from both primary and secondary schools was used.

Archibald conducted the study in Washoe County, Neveda, USA. The researcher used a three level HLM model and found a small negative relationship between school size and both math and reading (standardized regression coefficient β = −0.03 for reading and −0.07 for math).

Ma and McIntyre examined the effects of pure and applied mathematics courses on math achievement in Canada, using data from the Longitudinal Study of Mathematics Participation. Variables included in the multilevel model were student background variables, prior math achievement, course attendance (pure math, applied math, low-level preparatory math), school location, school SES, parental involvement, and school climate. Ma and McIntyre did not find a significant main effect. In the final model positive interaction effects of school size with course taking were found. Students taking pure math or students taking applied math in smaller schools had higher achievement in math than did students taking pure math or applied math in larger schools. The effects were small: “a difference of 100 students in enrollment was associated with a difference in mathematics achievement of 5 % of a standard deviation. A quarter of a standard deviation often indicates a difference that is substantial enough to warrant practical implications: to reach that level a reduction in school size between 400 and 500 students is required” (p. 843).

Five studies (8 samples) found positive effects, i.e., achievement declined as school size increased (Borland and Howsen 2003; Bradley and Taylor 1998; Foreman-Peck and Foreman-Peck 2006; Lubienski et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2012). For three of these studies the curvilinear relationship was examined as well (for these studies see the text on curvilinear relations below).

In the study by Lubienski et al. (2008) the relationship between school size and math achievement is examined both in primary and secondary education, using data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP 2003) on over 150,000 students in grade 4 (primary) and 110,000 in grade 8 (secondary). Variables included in the HLM models refer to school type, student demographics, school demographics, school location, school climate, teacher education and experience, teaching methods, and student beliefs and attitudes. The authors found that “school size is slightly positive associated with math achievement” (p. 129) in grade 8, and nonsignificant in grade 4. Moreover, they noted that the “demographic variables accounted for the vast majority of the variance in achievement between schools” (p. 128).

In the study by Sun et al. (2012) data were taken from the Hong Kong sample of PISA 2006. The dependent variable was science literacy. For statistical analysis, the authors used a two-level multilevel model. At the student level sex (male students performed better), student SES, parental views on science, motivation, and student self-efficacy positively contributed to student science achievement. At the school level, school SES composition, quantity of instruction and school size were found to be positive predictors of science achievement. A possible explanation the authors provide for the positive effect of school size on science achievement is that “larger student body schools are more likely to have more grants or financial opportunities and greater support from parents … Therefore, big schools are more likely to attract and retain qualified and talented science teachers as well as create large peer effects as more active and bright students work together” (p. 2118).

3.5.3 Curvilinear Relationships (School Size as a Quadratic Function)

Of the 46 samples in which school continuous variable, 8 samples (4 studies) also reported curvilinear relationships (Borland and Howsen 2003; Bradley and Taylor 1998; Foreman-Peck and Foreman-Peck 2006; Sawkins 2002) (see Tables 3.3 and A.4).

The study of Borland and Howsen is the only study providing evidence about the curvilinear relationship of school size effects on academic achievement of elementary (3rd grade) students. The study was conducted in Kentucky (United States). The mean school size of the 654 schools was 490 students. Other variables in the model included student ability, teacher experience, the existence of a teacher union, average income of the community, class size, and poverty. The results of the two-stage least-squares regression suggested an optimal school size of around 760 students.

The three studies related to secondary education were all conducted in the United Kingdom. All three studies focused upon the upper end of the exam results distribution, with either the proportion of 15–16-year-old pupils in each school obtaining five or more General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examination results at grades A to C in England (Bradley and Taylor) or Wales (Foreman-Peck and Foreman-Peck) as dependent variable, or the percentage of pupils in their last year of secondary education (S4) gaining five or more Standard Grade passes at levels 1 or 2 in Scotland (Sawkins). The estimates for the samples in England and Wales suggest an inverted `U’-shaped relationship between school examination performance and school size. For the schools in England (Bradley and Taylor) the optimum school size found was around 1,200 students for 11–16 schools and 1,500 students for 11–18 schools, optima that seem to be considerably higher than the mean school size of the schools in the samples (685–765 for 11–16 schools and 916–1,010 for 11–18 schools, see also Table 3.3). The optimum school size found for schools in Wales appeared to be much lower (560 students), both compared to the evidence in England and to the mean sizes of the schools in the Welsh samples (respectively 871 in 1996 and 936 in 2002).

In the study using Scottish data (Sawkins 2002), a contradictory ‘U’-shaped relationship was found between examination performance and school size. Scottish school examination performance appeared to decline as the number of pupils in a school increases, reaching a minimum turning point of around 1,190 pupils for the 1993–1994 sample and 1,230 pupils for the 1998–1999 sample, after which the performance started to increase. The explanation might be that in Scotland very large schools are uncommon. In the study by Sawkins, only 4 % of the secondary schools appeared to be larger than the calculated minimum.

3.5.4 School Size Measured as Categories

In 15 studies (18 samples), schools were classified in categories, based on the number of pupils. Six studies (6 samples), were conducted in primary education and 10 studies (8 samples) in secondary education (see Table A.5). The range of school sizes included in the studies was variable. Some studies compared small and larger schools while in other studies schools of three or more different size categories were compared.

In three samples (2 studies), a positive relationship between school size and achievement was found (large schools doing better) (Gardner et al. 2000; McMillen 2004) and in three other samples (2 studies) a negative association (Eberts et al. 1990; Lee and Loeb 2000). In 16 samples, the relationship was nonsignificant, and in the remaining six samples a certain size category or optimum was favored (Alspaugh 2004; Lee and Smith 1997; Ready and Lee 2006; Rumberger and Palardy 2005).

In their study of 264 inner-city elementary schools in Chicago Lee and Loeb (2000) found that school size influenced both teachers and students. In small schools (with 400 pupils or less) 1 year gains in math achievement were significantly higher compared to those in mid-size (400–750 pupils) and large schools 750 pupils or more). Both direct and (small) indirect effects were found, the latter through teachers’ positive attitudes about collective responsibility for student learning. The limited number of small schools participating in the study, however, was a drawback of the study. Only 25 of the 264 schools were small (400 pupils or less).

McMillen (2004) investigated the impact of school size achievement for three separate samples of students (at either elementary, middle, or high school level), using longitudinal achievement data from schools in North Carolina. At high school level, a positive and main effect was found of school size with both reading and math achievement after controlling for school and student demographic characteristics. Students in larger high schools were associated with higher achievement. But “the benefits of size at the high school level, however, appeared to accrue disproportionally … to higher–achieving students, white students and students whose parents had more education, especially in mathematics …” (p. 18). At the elementary and middle cohort the multilevel analyses yielded no statistical significant main effects for school size, but small interaction effects were found between size and prior achievement. Students who scored on grade level in the 3rd (respectively 6th) grade tended to do slightly better in larger middle and high schools. Students who scored below grade level in grade 3 (respectively 6) performed better in smaller schools. The interaction effects found at high school level (between size and ethnicity and size and parent education) were nonsignificant at primary and middle school level. McMillen also estimated curvilinear effects for school size. However, in all models tested, a better fit was achieved when only the linear term for school size was used. Possible explanations for the results found in the study refer to the broader curriculum offerings in large schools (higher achieving students in large schools might be able to take more advantage of these) (see also Haller et al. 1990; Monk 1994), and/or the culture and organization of small schools. Students from disadvantaged and minority background might have better achievement in small schools because of the better social climate and more personal relationships between students and teachers.

Rumberger and Palardy (2005) used data from the National Education Longitudinal Study (Nels: 88) to estimate the impact of school size on achievement growth, drop-out rate and transfer rate. The study was based on a sample of 14,199 pupils from 912 schools in the United States (nationwide) and was one of the rare studies in which achievement growth and drop-out rate were investigated simultaneously. Results of the multilevel analyses showed that “schools that are effective in promoting student learning (growth in achievement) are not necessarily effective in reducing drop-out and transfer rates” (p. 24). An “inverted U” relationship was found for achievement and drop-out. Achievement growth was significantly higher in large high schools (1200–1800 pupils) as was also the drop-out rate. Next to this, it was found that background characteristics contributed differently to the variability in the various outcome measures (i.e., 58 % of the variance in school drop-out rates, 36 % of the variance in student achievement and 3 % of the variance in transfer) as did also school policies and practices. When dropout was the dependent variable, school policies and practices accounted for 25 % of the remaining variance after controlling for student background. This was far more than for achievement or transfer.

The study by Luyten (1994) is the only Dutch study examining the association between school size and achievement included in the review. Luyten employed multilevel analysis to investigate the effect of school size on math and science achievement in the Netherlands, Sweden, and the US. Controlling for background characteristics (sex, achievement motivation, socioeconomic status, and cognitive aptitude), the study did not reveal any significant effects in any of the three countries.

3.5.5 Moderator Analyses

For the studies and samples in which school size was measured as a continuous variable moderator analyses were conducted to examine the degree to which the relationship between school size and achievement could be attributed to specific characteristics of the study or sample. Also we investigated whether the school size and achievement correlation was moderated by the academic subjects in the achievement measure.

The analyses of vote counts applied to studies and samples addressing the impact of school size on achievement in different subject areas does not show differences of importance (see Table 3.4). The percentage of positive effects (students in larger schools having better performance) for achievement in science and “all other subjects” is somewhat higher than those for language and mathematics.

Moderator analyses of study and sample characteristics examining the number and percentage of negative, nonsignificant, and positive effects of school size on academic achievement are presented in Table 3.5. Of the moderator analyses of study and sample characteristics, the statistical technique employed and the inclusion of a covariate for student’s prior achievement in the model tested are the most striking outcomes. More negative effects are found in studies that account for prior achievement as well as in studies that employed multilevel modeling.

3.5.6 Social Cohesion: Attitudes of Students and Teachers Toward School

Fourteen studies (15 samples, yielding in total 26 effect estimates) provided evidence about the relationship between school size and students’ and teacher attitudes toward school (see Tables 3.7, A.6, A.7). Evidence about the effects of school size on attitudes was mainly available from secondary education (12 studies; 13 samples). Only two of the 14 studies examined the impact of school size on students’ attitudes in primary education.

The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (9 studies; 10 samples). Other countries were Australia (1 study), Israel (1 study), Italy (1 study), and the Netherlands (2 studies).

The outcome variables (attitudes) measured in the studies could be classified into three main variables: identification and connection to school, relationships with students, and relationships with teachers (see Table 3.6). With regard to student attitudes identification and connectedness to schools the variables used included perceptions of pupils’ like feeling part of the school, feeling competent and motivated, feeling safe, being happy and satisfied with school, with education and the usefulness of their school work in later life. Relationships with students targeted at perceptions of being happy together as well as the kindness and helpfulness of their peers. The relationship with teachers is a variable in which relational aspects were included (e.g., the teacher treats pupils fairly and cares about them) as well as perceptions with regard to the support students receive (such as encouraging students to higher academic performance, helping pupils with school work).

As identification and connection to school is concerned, Kirkpatrick Johnson et al. (2001) distinguish between affective aspects (the feelings toward and identification with school, which he calls school attachment) and behavioral aspects (students’ participation or engagement). The latter refers to behaviors that represent participation, such as trying to their best in class, doing homework, and participate in extra-curricular activities. The authors further state that “theoretically, engagement and attachment are related to each other and to achievement. A student who feels more embedded in his or her school is more likely to exert effort, while one who participates in school and classroom activities is more likely to develop positive feelings about his or her school” (p. 320). Also, in previous research a positive relationship was found between identification and connection with aspects of schooling on the one hand and higher achievement and lower levels of problem behaviors on the other (e.g., Newmann et al. 1992; Bryk and Thum 1989; Gutman and Midgley 2000).

In this section, where the attitudes of students and teachers toward school are the outcome variable, we limit ourselves to attitudes to identification of and connection with school. Participation is addressed both in the section on involvement and in the section on other student outcomes.

Table 3.7 gives an overview of the number of studies, samples, and estimates included in the vote counting procedure for students’ and teachers’ attitudes to school. In total, 14 studies and 15 samples were included in the vote count. Two-third of the effects (derived from half of the 15 samples) between school size and attitudes to school appeared to be negative.

Two studies reported nonsignificant effects (Holas and Huston 2012; Kirkpatrick Johnson et al. 2001). Mixed effects were found in the studies by Crosnoe et al. (2004), Kahne et al. (2008), Van der Vegt et al. (2005). In these studies, both negative and nonsignificant effects were reported (see Tables A.8, A.9, A.10).

3.5.7 School Size Measured as a Continuous Variable

Eight studies reported linear negative effects of school size on attitudes to school. Five of these studies were conducted in the US, the other three in Australia, Israel, and Italy.

One the five US studies in which a negative effect was found is the study by McNeely et al. (2002). The authors used evidence from a sample taken from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (about 75,000 adolescents from 127 schools, grades 7–12). Average level of school connectedness of pupils was the dependent variable. This variable measured the degree to which students felt close to people at this school, felt safe, and felt part of the school, were happy and experienced that the teachers treated them fairly. Multilevel analysis was employed. Variables included in the model were student background characteristics at individual and school level, teacher qualifications, structural school characteristics, discipline policies and student participation, and classroom management. The results showed that small school size is positively associated with school connectedness, but the strength of this relationship was meager, as an increase of 500 students in school size was associated with a very small decline in school connectedness.

The studies not conducted in the United States focused on respectively the impact of school size on teachers’ organizational commitment in Israeli schools (Rosenblatt 2001), student engagement and participation in Australia (Silins and Mulford 2004) and students’ sense of community in the Veneto region in Italy (Vieno et al. 2005). Negative effects of school size on students’ attitudes and teachers’ attitudes were reported in the studies, respectively bySilins and Mulford (2004) and Rosenblatt (2001). Vieno et al. (2005) found a positive effect, although this effect was not significant. In this latter study, conducted in the Italian context, students’ sense of community was measured by a six-item scale (example items were “our school is a nice place to be, our students accept me as I am and when I need extra help I can get it from my teacher”). School size appeared to be nonsignificant in this study, as well as many of the other structural characteristics (e.g., facilities, extracurricular activities, and whether the school is public or private). SES was significant at the school level but not at the individual level. An intermediate variable positively associated with sense of community was democratic school climate, a variable better malleable to change than school size and other structural variables.

Silins and Mulford (2004) employed path modeling to examine the association between school size and SES on both students’ perceptions of teachers’ work in the class and students’ outcomes (such as attendance, participation in, and engagement with school). Engagement with school was operationalized as students’ perceptions with regard to the way teachers and peers relate to them, the usefulness of their schoolwork in later life, and the extent of identification with their school. School size had an indirect and negative effect on engagement through participation (i.e., absences, participation in extracurricular activities, preparedness to do extra school work, involvement in classroom decisions, etc., ES = −0.16). Students in large schools participated less and this was associated with less engagement.

In the study conducted in the Netherlands finally, mixed effects were found. Van der Vegt et al. (2005) reported a nonsignificant effect of school size on students’ connectedness with school and significant negative effects of school size on both relationships with peers and relationships with teachers.

3.5.8 Curvilinear Relationships

Like, McNeely et al., Crosnoe et al. (2004) also used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. The sample included 15,000 students from 84 schools. The mean school size was 1,381 (with a standard deviation of 838). Interpersonal climate was the dependent variable. It was measured with three variables: (1) student school attachment (the extent to which adolescents felt close to people at their school and felt a part of their schools), (2) student–teacher bonding (the extent to which adolescents believed that teachers treated students fairly and, felt that teachers cared about them), and (3) student extra-curricular participation. Multilevel modeling was applied to estimate the effects of school size. The intra-class correlation (amount of variation between schools) appeared to be smaller for school attachment and teacher bonding (3 and 5 %, respectively) than for extra-curricular participation (14 %). For school attachment and teacher bonding a curvilinear effect was found with the lowest levels of attachment and teacher binding occurring at a size of 1,900 or 1,700 students, respectively. For extracurricular participation, a negative linear effect was found. The authors conclude that, based on the results of their study, an optimal school size for school connectedness would be less than 300 students, considerably lower than the optimal size for academic achievement found in other studies.

3.5.9 School Size Measured in Categories

In two of the tree studies in which school size was measured in categories (Bowen et al. 2000; Lee and Loeb 2000) small schools were favored above larger schools. In the study by Bowen et al., the focus was on student attitudes. School satisfaction and teacher support were the dependent variables. In the study by Lee and Loeb the impact of school size on teachers’ collective responsibility was investigated by means of teacher attitudes, i.e., the extent of a shared commitment among the faculty to improve the school so that all students learn.

Bowen et al. conducted their study in middle schools in the US and used five size categories (the smallest 0–399 pupils, the largest 1,000–1,399 pupils). They found negative effects of school size on school satisfaction and teacher support and concluded that “schools with enrolments of 800 or more might be too large to ensure a satisfactory educational environment.” Lee and Loeb (2000) employed their study in 264 schools in Chicago. They found that compared to small schools (0–400 pupils) “teachers’ views about the prevalence of collective responsibility appeared to be more negative in medium-sized schools (400–750 pupils) and even more in large schools (more than 750 pupils)”.

De Winter (2003) also used three size categories in his study (less than 500, 500–1,000, more than 1,000 pupils), which was conducted in Dutch secondary education. He concluded that an optimal size, as far as school climate for pupils is concerned is that a school is neither too big nor too small.

3.5.10 Participation

Participation of students, teachers, or parents was the dependent variable in 10 studies (see Tables 3.9, A.11, A.12). With the exception of the study by Holas and Huston, in which primary and middle schools were sampled both, all other studies were concerned with secondary education. Nine studies were conducted in the United States and one in Australia (Silins and Mulford 2004).

Seven of the ten studies provided evidence on participation of students, one about teachers and two about participation of parents (see Table 3.8). In five studies, students’ participation was restricted to participation in extracurricular activities; in the remaining two studies a broader operationalization of participation was taken. In the study by Holas and Huston, school involvement included four aspects (school attachment, teacher support, negative affect toward school and school activity participation). Higher scores represented higher involvement. Silins and Mulford used a broad concept of students’ participation, including absences, participation in extracurricular activities, preparedness to do extra work, involvement in classroom/school decisions and setting own learning goals, and voicing opinion in class.

The study by Kahne et al. (2008) examined the impact of 4 years of small school reform in Chicago. A variety of teacher and student measures was included in the study, including teachers’ involvement in school decision making (see also the section on other dependent variables).

The impact of school size on participation of parents was examined in two studies. Dee et al. (2007) included four-dependent variables about parental involvement in their study, each variable measured through one single item. The item addressing the most intense involvement with school (i.e., volunteering at school) was chosen to be included in this review.

The results of the vote count for school size on participation are presented in Table 3.9.

In almost all samples a negative and significant association between size and participation was found despite different conceptualizations, outcome measurements, and types of respondents (see also Tables A.13, A.14). Although the number of studies is limited such a pattern of results supports the claim that smaller schools are associated with greater engagement. This was also found in other review studies (see Leithwood and Jantzi 2009).

A dissenting opinion came from the study by Lay (2007), titled “Smaller isn’t always better.” In this study data from the 1999, National Household Survey was used to examine the effects of school size on participation in school activities. School size was measured in three ways: based on parental answers about the enrollment of their child’s school (responses were classified in categories) as well as based on data taken from matching zip codes for each pupil respondent with the high school within its borders (data were both used to measure school size as continuous variable as well as classified in categories). Other variables in the model were race, parent income, and plan to attend college. Depending on the measurement of school size used the effects on school activities differed. In the model where school size categories were based on parental responses (with categories <300, 300–599, 600–999 and over 1,000) the association between school size and participation was nonsignificant. When school size was measured by a continuous variable (based on matching zip codes with each pupil response) the effect was significant and negative. Finally, when categories based on the continuous measure were used (with categories <300, 301–600, 601–900, 901–1,200, 1,501–1,800, and over 1,800) a curvilinear relationship was found, in which participation in schools with 1501-1800 students was significantly less likely. According to the author, concerns over the measurement of school size as well the limited number of student, school, and community variables included in the model may account for the few significant effects found.

Teacher influence was just one of the 10 teacher measures included in the multilevel models of a study on the implementation and impact of Chicago High School Redesign Initiative (CHSRI) (Kahne et al. 2008). In this initiative, large traditional neighborhood high schools (non-CHSRI schools) were converted into small autonomous ones. Data were collected for four successive waves of 11th graders starting in the 2002–2003 school year when three CHSRI conversion schools had 11th graders to the 2005–2006 school year when 11 CHSRI schools had 11th graders. Based on the theory of change ten teacher outcome variables (e.g., collective responsibility, quality professional development, teacher-teacher trust) were included in the study as well as ten student outcome variables (e.g., quality of English instruction, academic press, sense of belonging), and four outcomes (absences, drop-out rate, graduation rate, and achievement test scores). A great number of student and school level background variables were controlled for. Three level hierarchical linear modeling was used to estimate the significance and effects of the CHSRI schools compared to around the rest of the Chicago Public Schools (the non-CHSRI schools). The main conclusion is that “given the newness of the reform and the small size of the samples, it is clearly too soon to make broad claims about the efficacy of small school conversions in Chicago. … We see indications that small school conversions as promised provide a more personalized and supportive school context for students … We saw evidence that smaller schools enable the creation of contexts for teachers (e.g., ones characterized by greater trust, commitment. and sense of influence) but that these contexts do not appear to be fostering more systematic efforts at instructional improvement, different instructional practices, and improved performance on standardized tests” (p. 299).

3.5.11 School Safety

Evidence about the relationship between school size and school safety was derived from 24 studies (25 samples) (see Tables 3.11, A.15, A.16). Two studies were conducted in primary education (Bonnet et al. 2009; Bowes et al. 2009), one study used samples both from primary and secondary school students (O’Moore et al. 1997) and in three studies elementary and secondary school students were sampled together. The remaining 18 studies were conducted in secondary education. Thirteen studies were performed in the United States, five studies in The Netherlands (Bonnet et al. 2009; Inspectorate of Education 2003; Mooij et al. 2011; Van der Vegt et al. 2005; De Winter 2003), two in Israel (Attar-Schwartz 2009; Khoury-KassabrI et al. 2004), one in Ireland (O’Moore et al. 1997), one in the United Kingdom (Bowes et al. 2009), one in Canada (Leung and Ferris 2008), and one in Taiwan (Wei et al. 2010).

The outcome variables addressed in the 24 studies referred to various forms of student safety behavior, including (combinations of) disciplinary behavior, bullying, norm violating behavior, and different types of violence (see Table 3.10).

The summary of directions of effect for school size and safety is presented in Table 3.11 (for detailed information we refer to the Appendix, Tables A.17 and A.18). The results indicate that the number of negative and nonsignificant effects do not differ from each other.

3.5.12 Positive Relationships/Mixed Effects

Positive effects of school size on feelings of safety were reported in five studies. With the exception of the study by O’Moore et al. (1997) in which a sample from primary and secondary schools was taken, all studies were conducted in secondary schools. The findings suggest that pupils felt more safely in large schools (Mooij et al. 2011); that less bullying and fighting takes place in larger schools (Klein and Cornell 2010; O’Moore 1997; De Winter 2003), and that in larger schools pupils were more satisfied with the safety policy and regulations(Van der Vegt et al. 2005). In contrast to the findings of De Winter, Van der Vegt et al. reported a negative effect of size on bullying and fighting. The three Dutch studies (Mooij et al. 2011; Van der Vegt et al.2005; Winter 2003), and the US study (Klein and Cornell 2010) will be discussed below, the study by O’Moore in the section on curvilinear relationships.

Mooij et al. (2011) used data from almost 80,000 pupils, 6,000 teachers, and other staff and 600 managers from secondary school in the Netherlands to test a two level model of social cohesion influences on a pupil’s feelings of school safety. Personal background, level of attainment in education, school measures against violence (pro-social discipline) were positively associated with feelings of safety at school. Negative directions of effect were associated with not feeling at home in the Netherlands, peers taking drugs and weapons into school, by pupil’s experiencing social violence, severe physical violence, and sexual violence as well as by staff experiencing severe physical violence. Curriculum differentiation based on learning differences (the streaming process of pupils into secondary schools) also had a negative effect on feelings of safety. The effect of school size was positive: pupils felt more safely at larger schools. However, when interaction effects were added to the model (i.e., the interaction of school size with pupil social violence), the main effect for school size on pupil’s feelings of safety became insignificant. The authors conclude that “given the present results national policy should try to increase the safety of pupils and staff in school by enhancing pro-social rules of conduct and the shard control of these rules, taking school measures against truancy and redefining curriculum differentiation procedures” (p. 385/386).

Van der Vegt et al. (2005) investigated the effect of school size on feelings of safety, the availability of a safety policy, and the occurrence of bullying and fighting and vandalism, drugs and theft. About 5,000 secondary school pupils participated in the survey. Regression analysis was applied. The results found were both negative (more bullying and fighting, vandalism, drugs and theft at larger schools) and positive (pupils in large schools more satisfied with the safety policy and safety measures). School size had no effect on the perceptions (feelings) of safety.

De Winter (2003) found opposite effects, in this study being bullied, bullying and fighting occurred significantly more at smaller secondary schools, also after correction for level of attainment (school type, i.e., different streams of secondary education) or urbanicity. According to the author, an explanation might be that, as students at smaller schools do have more intense relationships with their peers, then more frequent bullying and fighting obviously might also be part of these contacts.

The study by Klein and Cornell (2010) is the only one of the 13 US studies that found positive effects. In this study, the data were collected in three different ways, by means of (1) student and teacher perceptions of victimization, (2) student self-reported number of experiences with victimization, and (3) rates of victimization based on school discipline records. Three types of victimization were the dependent variable (i.e., bullying, threats, and physical attacks). Other variables included in the model were poverty, proportion nonwhite students, diversity, and urbanicity. Regression analysis was applied. The results were mixed. When teacher and student perceptions of victimization were the dependent variable, the results indicated a negative effect (with significant higher levels of violence perceived in larger schools). However, nonsignificant effects were found when student self-reports of being a victim of violence were used. And if discipline violence rates were the measure, the results indicated a positive association. These contradictory findings suggest the need for a closer examination of the measures of victimization used: “If large schools truly have a higher rate of student victimization, it will be necessary for these schools to adopt stronger safety policies and prevention issues, but if the problem is one of perception only, then school authorities should focus on educational efforts to reassure students and help them to feel safe” (p. 943).

3.5.13 Negative Relationships

An inverse relation between school size and safety was reported in 11 studies (Attar-Schwartz 2009; Bowen et al. 2000; Chen 2008; Chen and Vazsonyi 2013; Eccles et al. 1991; Leung and Ferris 2008; Stewart 2003; see also Bowes et al. 2009; Gottfredson and DiPietro 2011; Haller 1992; Van der Vegt et al. 2005).The effect might be small (with an increase of e.g., 500 pupils in a school increasing the risk for being a victim of bullying after controlling for neighborhood and family background variables and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors, see Bowes et al. 2009), or discontinue, i.e., school size only matters for schools of a certain size category (see Leung and Ferris 2008).To explain evidence on the association between school size and safety in some studies it was argued that other school organization conditions than size might be more likely to influence safety (see Stewart 2003).

Leung and Ferris (2008) examined the effect of school size on self-reported teenage incidence of violence of 17-year-old low SES French speaking males in Montreal, Canada, controlling for social and demographic characteristics. School size was measured both continuously and classified into four size categories (1,000 or less, 1,000–1,499, 1,500–1,999, 2,000 or more). Control variables included in the binary logistic model were drop-out status, average family income at school level, family structure, delinquent friends, and parent’s education. Depending on the measure of school size used, the results of the logistic regression analysis differed. School size measured continuously was significantly (negatively) associated with teenage violence. The authors also calculated marginal effects. For school size in the continuous model this implied that “an increase in school enrolment of one thousand would lead to about a 10 % increase in the probability of teenage violence” (p. 328). When school size was measured discretely (broken down into four size categories) only for very large schools a negative effect was indicated. “It’s marginal effect suggests that teenagers who attended a school with more than 2,000 students were about 22 % more likely to engage in violent behavior than those who attended schools with less than 1,000 students” (p. 328). No significant effects were found for small -and large medium-sized schools.

School delinquency/misbehavior was the dependent variable in the study conducted by Stewart (2003). In this study, data were used from the second wave of the National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS). More than 10,000 10th grade students within 528 schools participated in the study. School misbehavior was measured by means of a scale asking pupils how often during the first half of the current school year they got in trouble for not following school rules, were put on an in-school suspension, suspended, or put on probation from school and got into a physical fight at school. Multilevel modeling was applied to examine the effects six of school level and 14 pupil level covariates on school misbehavior. Two school level variables in the model were significant: school size and school location. Larger schools in urban areas had significantly higher levels of school misbehavior. At individual level 10 of the 14 covariates were found significant, including three of the four school social bond variables distinguished in the study. Higher levels of school attachment, school commitment, and beliefs in school rules were positively associated with lower levels of misbehavior. School involvement, the 4th social bond variable, was (positive but) not significantly related to misbehavior. A further interesting result of this study is that the other school covariates (school composition, school poverty, school social problems, and social cohesion) were not significantly associated with school misbehavior.

3.5.14 Curvilinear Relationships

The only study that reported curvilinear relationships was the study by O’Moore et al. (1997). This study was conducted in Ireland in both a sample of primary and secondary schools. Three categories of size were distinguished (less than 200 students, 200–499 pupils, and 500 pupils or more). The results were mixed. In primary schools no significant differences were found between school size categories and the incidence of being bullied, while in secondary schools the chance of being bullied was least common in large schools. With regard to bullying others, both in primary and secondary education the highest proportion of pupils who bullied others were found in medium-sized schools.

3.5.15 Moderator Analyses

For the studies and samples in which school size was measured as a continuous variable moderator analyses were conducted to examine study and sample characteristics that may account for the differences of directions of effect found (see Table 3.12). The statistical technique employed and if a study was conducted in the United States are the most prominent outcomes. More negative effects are found in studies applied in the United States, as well as in studies that did not apply multilevel modeling. More significant effects (both negative and positive) were found if urbanicity was controlled for.

3.5.16 Student Absence and Dropout

Twelve studies (15 samples) reported on evidence about attendance, truancy, or absenteeism. The effect of school size on dropout was examined in four studies (5 samples). Almost all studies (and samples) were conducted in secondary schools, with one study reporting evidence from primary schools (Durán-Narucki 2008) and two studies employed in samples of both primary and secondary students (Eccles et al. 1991; Heck 1993). With the exception of the study by Bos et al. (1990), conducted in the Netherlands and the study by Foreman-Peck and Foreman-Peck (2006) conducted in Wales (United Kingdom), all studies relate to the context of the United States. Two studies (Gardner et al. 2000; Kahne et al. 2008) investigated the effect of size on both absenteeism and dropout.

The predominant outcome variables included in the studies were attendance, absenteeism, and drop-out rate (see Tables 3.13, 3.14, A.19, A.20, A.21, A.22). Perceptions with regard to truancy and absenteeism were measured in just two studies.

Before calculating the vote counts, the results of some studies were rescored, so that in all cases a positive effect denotes a situation of high attendance and less absenteeism, truancy or drop-out.

Table 3.15 shows the summary of the vote counts for studies in which attendance or truancy were the dependent variable. One study (Durán-Narucki (2008) reported a positive relationship between school size and attendance rate. Four studies reported negative effects (less attendance in larger schools) (Eccles et al. 1991; Foreman-Peck and Foreman-Peck 2006; Haller 1992; Jones et al. 2008). Mixed effects were reported in three studies (Kahne et al. 2008; Kuziemko 2006; Lee et al. 2011) and nonsignificant relationships in three studies as well (Bos et al. 1990; Chen and Weikart 2008; Heck 1993). One study (Gardner et al. 2000) reported evidence favoring small schools (see also Tables A.23, A.24).

With regard to drop-out, three of the five studies reported significant differences between size categories. In the fourth study (Kahne et al. 2008), in which a linear effect of size was investigated, no statistically significant relations were found (see also Table 3.16, A.25, A.26).

3.5.17 Positive Relationships/Mixed Effects

Durán-Narucki (2008) investigated the relationship between the quality of school building facilities and poor English Language Arts and math achievement (i.e., percentage of students that scored on the lowest level) in 95 elementary schools in New York City. Attendance, measured as the average percentage of days attended school in a school year, was included as a potential mediator variable in the study. Covariates in the model were concentrated ethnicity, SES, teacher quality, and school size. The findings of the regression analysis indicated that school size was significantly and positively related with daily attendance, i.e., the study found significantly higher attendance in larger schools. The effects of school size on the percentage of students having poorer performance in English and math achievement were negative, but did not reach statistical significance. School attendance mediated the relation between school building condition and achievement, fully for poor performance in English Language Arts and partially for math. The author did not provide an explanation for the effect of size found in the study.

Lee et al. (2011) investigated the effectiveness of the Ohio High School Transformation Initiative (OHSTI) on attendance, graduation, dropout rates, and performance index scores. This school improvement initiative focused on transforming large high schools to small learning communities. In the Initiative a large school is defined as above 800 students, a small learning community as 100 students per grade level or 400 students in total. Between 30 and 35 schools participating in the study were small schools, approximately 200 schools were defined as large but being similar to the OHSTI schools. Mann-Whitney tests were performed to analyze attendance rates between small and large schools over 5 school years. In the first four years of the Initiative no significant differences were found between small and large schools, in the most recent school year (2007–2008) the attendance rate was significantly lower in small schools. Regarding drop-out rates (these were compared at grade level instead of school level and therefore not included in the review), the findings of the study indicated no consistent pattern. Although the study “observed some progress in small schools “the authors stated that “small schools programs alone are not the answer to improve education” (p. 25). Creating sense of community, extending the school day or year for students who need it and attracting and retaining effective teachers might be key factors as well.

3.5.18 Negative Relationships

Four studies reported negative effects (less attendance in larger schools). In two of these studies student and teacher ratings with regard to absenteeism were the outcome measure (Eccles et al. 1991; Haller 1992), while in the other two the effect of size on (attendance) rate was examined (Foreman-Peck and Foreman-Peck 2006; Jones et al. 2008).

Eccles et al. (1991) used data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS: 88). They found absenteeism, violence, and substance abuse significantly more often being reported as a major problem in larger schools by both teachers and students. Haller (1992) came to the same conclusion. In his study, perceptions of school level student indiscipline (truancy and vandalism/theft) was estimated from three sources (student, teacher, and self-reports) and regressed on school size and ruralness. The results show that ruralness and size together add significantly to the variance explained. Size appeared to be more important than ruralness. Interaction effects were also found: “the larger a rural school …, the greater its level of indiscipline” (p. 152). In the conclusion the authors hold a plea for other criteria than improving student behavior underlying decisions on consolidating schools (such as equity and efficiency). As far as student behavior is concerned, implementing relatively easy malleable school practices (such as identifying all pupils not attendant each morning) might be even effective as well.

3.5.19 Nonsignificant Relationships

Chen and Weikart (2008) investigated the relationship between school size, school disorder, student attendance, and achievement. The model builds upon the School Disorder Model (Welsh et al. 2000) and was extended for this study with student achievement. 212 middle schools in New York City participated in the study. Percentage free lunch and percentage white students were the control variables. Structural Equation Modeling was applied. Higher school disorder (β = −0.10), a lower attendance rate (β = −0.08), and lower achievement (β = −0.02) were found in larger schools but the effects were not statistically significant. The hypothesis that “school size has an indirect effect on academic achievement mediated by school disorder and student attendance rate” could also not be confirmed (p. 15). However, the results indicated a strong positive relationship between attendance rate and achievement (β = 0.54). Like Eccles et al., Chen and Weikart also suggest to focus on measures to improve school climate, including attendance policies, instead of reducing school size.

3.5.20 School Size Measured as Categories

Three studies reported differences on attendance or dropout rate between various school size categories (Gardner et al. 2000; Lee and Burkam 2003; Rumberger and Palardy 2005). Gardner et al. compared small Californian public schools (between 200 and 600 pupils) and large schools (2,000 pupils or more). Student achievement (four measures), absenteeism, and dropout were the dependent variables. The results indicated a significant positive effect of school size on all student achievement measures. At the same negative effects were found for absenteeism and dropout. So students at larger schools performed better, but were more absent and dropout in large schools was significantly higher. This was also the conclusion in the study by Rumberger (1995). In this study (see the section on student achievement for a more elaborated description) an “inverted U” relationship was found for achievement and drop-out with large high schools (1,200–1,800 pupils) having significant higher achievement gain but also higher drop-out rates.

Lee and Burkam (2003) study built on the study by Rumberger (1995). Lee and Burkam also used the longitudinal data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS: 88). The sample consisted of 3,840 students in 190 schools from the High School Effectiveness supplement of NELS: 88. Whether a student dropped out between 10th and 12th grade was the dependent variable. Four categories of school size were compared (<600, 601–1,500, 1,501–2,500, >2,500). Binary logistic multilevel modeling was applied. The results indicated that “compared to medium-sized schools (601–1,500 pupils), large and very large schools have higher drop-out rates. This was particularly true for large schools (nearing a 300 % increase in the odds of dropping out, p < 0.001). Small schools also had higher dropout rates than medium-sized schools (more than a 100 % increase in the odds, p < 0.10)” (p. 22). Interaction effects indicated that in public or catholic schools of small and medium size with positive student–teacher relations, the probability on drop-out is less. The final model explains 12 % of the between school variance of drop-out. Besides the school level factors included in this study (school demographics, schools’ academic organization, and schools’ social organization) other factors might be of influence as well.

3.5.21 Other Student Outcome Variables

Six studies reported on school size effects on other student outcomes, i.e., student attitudes towards self and learning, and engagement (see Tables 3.17, A.27, A.28). One of these studies collected data from primary schools and middle schools (Holas and Huston 2012), the remaining studies all included evidence from secondary schools. One study (Inspectorate of Education 2003) was conducted in the Netherlands, the other six studies in the United States.

The results were mixed (see Tables 3.18, A.29, A.30). Two studies (Coladarci and Cobb 1996; Holas and Huston 2012) reported nonsignificant relationships between school size and student outcomes, two other studies reported negative effects (Lay 2007; Weiss et al. 2010). For one study (Kirkpatrick Johnson et al. 2001), a nonsignificant effect was found at the primary level, while at the secondary level larger schools were associated with less student engagement. In the study by Lay (2007) the direction of effect found differed depending on how school size was measured. When school size categories were the independent variable (either based on parental responses or on the continuous measure) a curvilinear relationship was found (with students in schools with fewer than 300 students significantly more likely to volunteer in community services). However, when school size was measured continuously, the relationship between size and participation was nonsignificant.

3.5.22 Attitudes

Two studies, one in US middle and one in US high schools investigated the relationship between school size and student attitudes. Coladarci and Cobb 1996 examined the indirect effect of school size on 12th grade academic achievement and self-esteem through (total time spent on) extracurricular participation. Using evidence from the National Educational Longitudinal Study of 1988 database, only students who attended either a small high school (less than 800 pupils) or a large high school (1,600 or more pupils) were considered in the study. Structural equation modeling was applied. Variables included in the model were prior self-esteem and prior achievement, SES, size, total extracurricular participation and total time spent on extracurricular participation. The authors did find a significant negative effect of school size on extracurricular participation (β = −0.210), with higher extracurricular participation among students attending smaller schools. The indirect effects of school size on achievement (β = −0.005) and self-esteem (β = −0.015) through extracurricular participation were negative, but not significant.

Holas and Huston (2012) applied path analysis to compare student achievement, school engagement and perceived efficacy and competence in English and math of students starting middle schools in 5th and 6 grades compared to students of the same grade in elementary schools. School characteristics (observed classroom quality, teacher-related classroom quality, school percentage of minority and poor students, and school size) were included in the path model as intermediate variables.The authors did not find significant effects of school size on any of the outcome variables of students in 5th grade. In 6th grade, school size was negative and significantly related to school engagement. In 6th grade, the study failed to find significant associations between size and perceived self-competence or achievement.

3.5.23 Engagement

Three studies investigated the impact of school size on student engagement in schools (Kirkpatrick Johnson et al. 2001; Lee and Smith 1995; Weiss et al. 2010). In these studies engagement in school was operationalized in very different ways (see Table A.27). Lee and Smith (1995) used the concept academic engagement, a composite of eight items measuring student behavior related to work in class. Kirkpatrick Johnson et al. (2001) focused on engagement in school (operationalized as attendance, attention for school work and doing homework), while Weiss et al. (2010) used a very broad composite measure of engagement based on seven variables: teacher experience, delinquent behavior, academic friend, educational motivation, teachers’ belief about ability, school preparedness, and parental involvement.

Lee and Smith (1995) investigated the effects of school size on achievement gain and academic engagement, using data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study 1988. Their analysis controlled for school restructuring practices, SES, minority status, initial ability, average school SES, minority concentration, sector, academic emphasis, and course-taking differentiation. The authors found both significantly higher and more socially equitable achievement gain and academic engagement in smaller schools. In the discussion of the article the authors wonder whether reducing school size really is the issue. “We would not draw that conclusion from our results. … Rather the findings indicate that the size of enrolments act as a facilitating or debilitating factor for other desirable practices. For example, collegiality among teachers, personalized relationships, and less differentiation of instruction by ability … are more common and easier to implement in small schools” (p. 261/262).

Weiss et al. (2010) also investigated the impact of size on achievement and engagement in US high schools. Using data from the Educational Longitudinal Study (ELS 2002) they found that “there are significant differences related to student engagement between schools of different size categories, while school size is not significantly related to mathematics achievement. Compared with students attending schools of the smallest size (the omitted category in the multilevel analysis), those in schools with 1,000–1,599 students or with more than 1,600 students have (significant) lower levels of engagement” (p. 170). Differences related to demographic characteristics were also examined in the study. Students previously held back were significantly less engaged, students from higher educated parents, students with higher SES, students with Hispanic background and females have significantly higher engagement. African–American students were not significantly different in engagement than white students.

3.5.24 School Organization and Teaching and Learning

Three studies in the review included measures of the impact of school size on school organization and teaching and learning (see Table 3.19). These studies had different aims and scope.