Abstract

This chapter examines the relationship between involvement in churches and individual volunteering activity in the wider community in Australia. The findings confirm the importance of the degree of a person’s church involvement, demographics and theological orientation in predicting individual volunteering by church attendees in the wider community. Church attendees’ stated reasons for volunteering formed a pattern which did not vary across four domains of volunteering beyond the congregation, with altruistic and religious reasons being the most common reasons for volunteering activity. However, a distinction emerges in the findings between individual volunteering activity and collective involvement by the congregation in the wider community. The sense of collective efficacy among church attendees was strongly associated with the extent of congregational bridging to the wider community, but did not predict individual volunteering activity. The role of collective efficacy raises questions about the focus of congregations and the need for vision and goal setting as key ingredients in congregational life. The research sheds light on the relationship between bonding and bridging capital, and shows that the relationship is not a simple one. Bonding and bridging are quite strongly related where it is congregational rather than individual bridging activity that is in view.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Christian churches are significant organizations in western society that subscribe to the value of helping others. Churches have long played a role in meeting social and welfare needs, for example through congregations and parishes working in their local communities. Help may be provided through the programmes and agencies of Christian denominations, sometimes acting on their own initiative or, in some contexts, on behalf of governments. Such help may be given through individual church attendees volunteering to take part in the activities of community organizations which may have little or no connection with their church involvement.

One way of conceptualising these relationships between individuals, congregations and the wider community is through a social capital framework. The social capital theorist, Robert Putnam , defined social capital as ‘those features of social organization, such as trust, norms and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions’ (Putnam 1993, p. 167). As significant social institutions, churches have often been viewed as making a positive contribution to social capital. Putnam has observed that faith communities are the single most important repository of social capital in America and has identified the links between religiosity and increased volunteering, giving and civic engagement (Putnam 2002; Putnam and Campbell 2010). Formal volunteering through not-for-profit organizations such as churches has been described as the core of social capital, as people come together in an organised way for the benefit of others (Leonard and Onyx 2004).

Although there has been some debate in the literature about the best way to define social capital, all conceptualizations of social capital refer to the advantages that accrue from social networks. Thus, activities that increase opportunities for social networking should increase social capital. This has led researchers to consider the level of participation in activities and organizations as good indicators of within-group social capital, assuming that as people become more involved in a group, their network of relationships will grow and strengthen. As van Staveren and Knorringa (2007) point out, it is the dynamics within and between groups that generate social capital.

A distinction has been drawn in the literature between bonding social capital and bridging social capital (Woolcock and Narayan 2000). Bonding social capital is associated with dense, multiplex networks, long-term reciprocity, thick trust , shared norms and less instrumentality (that is, not specifically developed for personal or group advantage). Bridging social capital is theorised to be associated with large, loose networks with weak ties, relatively strict reciprocity, thin trust, greater risk of norm violation and more instrumentality (Leonard and Onyx 2003).

The focus of this chapter is on bridging social capital as it occurs in relation to Christian congregations. ‘Bridging’ has been used in different ways in the literature, including:

-

The extent of relationships beyond a group. These can include ties that congregations create with social service agencies and the relationships that members of one group can create by participating in other groups (Wuthnow 2004).

-

Relationships that cross demographic divides such as class or ethnicity (e.g. Portes 1998).

-

Bridges across gaps between networks where there has hitherto been little connection (e.g. Burt 2004), which may occur as a result of geographic distance or organizational structure.

-

The capacity to access resources such as information, knowledge and finance from sources external to an organization or community (e.g. Woolcock and Narayan 2000).

This chapter follows Paxton’s (1999) description of bridging and bonding social capital as between-group and within-group social capital. In the current chapter, ‘bonding’ will refer to the social capital that may be developed within a congregation and ‘bridging’ will refer to the social capital that develops through church attendees interacting with other groups in the wider community, including volunteering. It should be noted that under this definition, denominational organizations would be considered to be outside the congregation, the relationship between them being more typically a form of bridging than bonding. Compared with the bonding between attendees within a congregation, the links between a centralised denominational organization and its congregations would be characterised by far fewer personal relationships than within the congregation itself, more obvious and explicit terms of reciprocity and thin trust. In terms of instrumentality, agency is often the focus between the denominational organization and the congregation, with volunteering and financial giving occurring principally to increase agency. Even the more local situation between a congregation and a school within a parish would carry many of the hallmarks of bridging.

An aspect of bridging that has received little attention in the literature is whether the bridge is formed by an individual, a subset of the group such as a delegation or the majority of the group. Although Burt (1998) has demonstrated the advantages to an individual of bridging, a group might expect a greater advantage if the bridging was more of a group-based activity. This chapter will consider bridging activity both as an activity carried out by individual attendees in volunteering beyond their congregation, and as a group activity which a section of or all the congregation may undertake in the wider community.

This chapter will also consider the relationship between bridging and bonding, which has received at least some attention in the literature. It has been concluded that excessive bonding can restrict the possibilities for bridging (Fukuyama 1995; Granovetter 1973; Molina-Morales and Martínez-Fernández 2010; Portes 1998; Rostila 2010). However, others question the direction of causation where there is strong bonding and little bridging (Crowe 2007; Donoghue and Tranter 2010). For instance, building up the internal resources of a group can be a legitimate strategy, especially when it appears that there are few opportunities to acquire external resources through bridging, as in the case of minority groups experiencing discrimination.

The examination of the impact of bonding upon bridging raises the broader question of what are the motivations that lead individual church attendees to volunteer in the wider community. To what extent does bonding experienced within the congregation itself account for individuals being motivated to volunteer for other community organizations and to what degree is it a function of the individual’s own beliefs? The literature on volunteer motivations is large and complex with numerous approaches and typologies. Some examples are Deci and Ryan’s (2000) self-determination theory, which focuses on the three core psychological needs of competence, connectedness and autonomy ; Edwards’ (2005) eight dimensions of motivation among museum volunteers (personal needs, relationship network, self-expression, available time, social needs, purposive needs, free time and personal interest); the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (2001) two motivational categories of helping others or the community and gaining personal satisfaction; Shye’s functioning modes of cultural, social, physical or mental wellbeing (Shye 2010).

The Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI, Clary and Snyder 1999) was selected as the basis for identifying motivations in this research because it has been developed with large samples and used effectively in a wide variety of contexts. The functional approach allows for the possibility that people will have multiple motivations for volunteering. The six motivations identified provide a good range of distinct motivations broadly covering those that appear in most other typologies. The VFI categories are: values, expressing or acting on important values such as humanitarianism; understanding, learning more about the world or using skills; enhancement, growing and developing psychologically; career, gaining career-related experience; social, strengthening social relationships and protective, reducing guilt or addressing personal problems. However, none of these typologies of volunteering specifically cover religious motivations and it was important that survey respondents were able to recognise the types of reasons with which they would be familiar. So in the present research, items used were based on the VFI categories and some items were added to address religious motivations.

Churches and Volunteering in Australia

The present research has been conducted in the context of Christian churches in Australia , in order to identify the nature of bridging between church congregations and the wider community. The research was partly funded by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Projects grant and was conducted jointly by the University of Western Sydney and NCLS Research. The focus of the research on churches reflects the interests of the partner agency, NCLS Research, a research group supported at the time of the study by the Catholic , Anglican and Uniting Churches .

Most Australians identify with a Christian denomination. In the 2011 national census (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011), 61 % of Australians identified as Christian, 22 % had no religion and 9 % did not state a religious affiliation . Only 7 % identified with a non-Christian religion. Far fewer, however, attend a church regularly. The International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) survey found that 16 % of Australian adults claimed to attend church monthly or more often, with 13 % claiming to attend every week or nearly every week (ISSP 2009). Church headcounts point to even lower rates of attendance, with an estimated 1.66 million people attending Catholic, Anglican and Protestant churches each week, or 8.8 % of the then population of 18.77 million people (Bellamy and Castle 2004).

From a historical perspective, the churches in Australia have been very active both in the establishment of charities for furthering social welfare objectives and in the establishment of schools. The Catholic Church is the largest non-Government provider of school education in Australia. Catholic, Anglican and Uniting Churches as well as the Salvation Army run most of Australia’s largest charities. Thus, churches in Australia provide the social organizations necessary to carry out significant volunteer work.

Although many studies have found a positive relationship between a person’s religiosity and volunteering (e.g. Shye 2010; Perry et al. 2008 ), other studies have found a weak relationship or none (Yeung 2004, p. 402). In the Australian context, research has generally found that religion has a positive impact on volunteering; people’s religious identity and frequency of attendance at religious services are both related positively to volunteering (Lyons and Nivison-Smith 2006). Furthermore, there is a positive correlation between hours spent on volunteering within congregations and hours volunteering beyond congregations (Leonard and Bellamy 2006, 2010).

One of the reasons for the different outcomes in studies of the relationship between religion and volunteering may be the kind of volunteering that is looked at. Although most churches employ paid staff, many roles are carried out by volunteers. In Australia, it has been found that around 50 % of church attendees have a voluntary role of some kind within the congregation; these roles can include preaching, leading worship , running groups for children and youth and administrative and business roles (Bellamy and Kaldor 2002). Volunteer roles are necessary for the successful operation of church congregations. This kind of volunteering needs to be distinguished from volunteering in community groups or social service organizations outside of the church, which is the subject of this chapter.

A related question for researchers in Australia has been whether the relationship between volunteering and religion is best explained by individual belief and commitment, or whether it is better explained by the activity of congregations in recruiting attendees into volunteer work. Lyons and Nivison-Smith (2006) found that committed belief was the key driver of individual volunteering, not the impact of religious networks. However, other Australian researchers have found that churches are important sites for volunteer recruitment, suggesting the importance of relationships and networks within congregations (Hughes and Black 2002; Evans and Kelley 2004).

The current chapter examines both sides of this question. The advantage of drawing upon a sample of church attendees is that the study has been able to look at the impact of various aspects of congregational life and the theological orientations of church attendees in some detail. Whilst it is not possible in such a sample to examine the relative impact of unbelief or of different faiths, the study has been able to consider the effects of different theological orientations in a nuanced way that would not have been possible in a broader population study.

There are tens of thousands of not-for-profit organizations in Australia, ranging from small arts and craft organizations and local sports clubs through to large social service organizations and charities. Given the range of volunteering activities in the wider community, it is likely that motivations for involvement will vary with the type of activity. In Australia, volunteering for recreation and sporting organizations is the largest domain of volunteering activity, accounting for 37 % of volunteers. Volunteering for community and welfare organizations (22 %) and education and training organizations (18 %) are the next largest domains, apart from volunteering for religious organizations such as churches (22 %). Volunteering for social action, social justice or lobby activities are among the smaller categories of volunteering (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010). These four domains were selected for detailed study because they accounted for the majority of volunteering activity outside of local churches and also covered many of Australia’s church-run charities and schools. Examining these domains provided the best approach, within the constraints of the survey, for gaining an appreciation of volunteering by church attendees beyond their local church, with only minimal deviation from what would be the overall picture had it been possible to explore all domains in depth.

A further aspect to consider in relation to volunteer motivations is whether the community organization that is the context for the volunteering is itself a church-run organization or a secular organization. This aspect will also be examined in the current chapter in relation to volunteer motivations as the type of motivation may vary among church attendees depending upon whether the community organization is run by a church, has a Christian heritage or is a purely secular organization.

Research Questions

The discussion suggests at least two sets of research questions for examination. The primary set of questions is to do with the relationship between congregational bonding capital and congregational bridging to the wider community. These primary research questions are:

-

Does congregational bonding stimulate individual volunteering in the wider community and, if so, how?

-

Does congregational bonding stimulate collective bridging to the wider community and, if so, how?

A secondary set of research questions considers the types of stated personal motivations found among church attendees who volunteer in the community. Answers to these questions extend the understanding of how bridging is occurring between Christian congregations and the broader community. Such questions include:

-

While religious motivations play a major role in individuals volunteering within congregations, how important are such motivations when it comes to church attendees volunteering beyond the congregation?

-

Are the main stated reasons for volunteering altruistic, instrumental or more intrinsically ‘religious’?

-

How do these stated motivations vary depending upon the type of volunteering context (e.g. whether the community organisation is church-run or secular)?

Method

Data Collection and Sample

The National Church Life Survey (NCLS) is a major survey of church attendees aged 15 years or over carried out every 5 years, involving all the major Christian denominations in Australia. Attendees at participating congregations complete a four-page survey. In the 2006 NCLS, respondents were asked to indicate if they would be interested in participating in further research by becoming part of a research panel. This chapter draws on data obtained from this research panel of church attendees drawn from across Australia.

Those attendees who indicated their interest in taking part in further research were sent a preliminary questionnaire for a study of social capital. More than 6,000 attendees completed this preliminary questionnaire that identified their demographic and religious profiles. Of these, 3,363 responded to a second, much longer questionnaire. Participants who had provided email addresses were sent emails with a hyperlink to a website containing this main questionnaire. Those without email addresses (about half of the entire panel) were mailed the main questionnaire. An individual code linked the data from the preliminary and main questionnaires for each respondent.

Most respondents to the main questionnaire were religiously committed people, with nine out of ten attending church weekly or more often. Most respondents (79 %) had a voluntary leadership or ministry role at their church for example in administration, children’s ministry, music or teaching. The respondents tended to be older than church attendees generally, with 78 % being aged over 50 compared with 59 % of attendees in the NCLS. Just over half of the respondents were female (52 %). Some 45 % of respondents had a university degree and about half were employed (full-time or part-time) or self-employed. Some 8 % of participants were born in a non-English speaking country, which is about the same proportion as found in the NCLS.

Individuals were asked about their experience of their congregation and their own levels of activity at church. Other questions were asked about their perceptions of their congregation. These questions treated the respondent as a key informant and examined the respondent’s impression of their congregation’s level of bonding. Respondents will differ in their knowledge of their congregation and so some will be better key informants than others. The potential negatives of being in groups cannot be ignored (Abbott 2009), so respondents were also asked about perceptions of congregational divisions and conflicts.

Scale Development

As mentioned in the Introduction, bridging has been defined in the current chapter as between-group social capital and bonding as within-group social capital, where the group is the congregation. Bridging activity can be seen as both an individual activity of attendees volunteering beyond their congregation, and as a group activity which a section of, or all, the congregation undertake together in the wider community .

A number of the key concepts in the study, including bonding, bridging and volunteering activity, have multiple facets and are generally not susceptible to measurement through the use of a single global item. Consequently scales were derived from multiple items by using Exploratory Factor Analysis on one half of the sample and then confirmed on the other half using Confirmatory Factor Analysis in Mplus. All scales achieved a reliability of 0.7 or more as measured by Coefficient H, indicating good scale reliability (Holmes-Smith 2011). Two bridging scales were developed which measure individual volunteering in the wider community and congregational bridging to the wider community. Three sub-scales were developed which measure different aspects of congregational bonding.

Individual Volunteering in the Community Scale

Arising out of the factor analysis, a scale of individual volunteering in the wider community was created from the following items:

-

Hours of volunteer work carried out in the wider community in the past month

-

Number of wider community organizations participated in during the past 2 years

-

Number of wider community organizations for which volunteer work was carried out in the past 2 years

-

Having been a spokesperson for a wider community organization/group in the past 2 years

-

Your advice was sought on a community issue in the past 2 years (excluding surveys)

Congregational Bridging Scale

Four items in the survey were scaled to measure the degree of congregational bridging to the wider community. The data is from the viewpoint of the respondent as a key informant of congregational activity; as a further stage in the research, it is intended to add more objective data from the larger National Church Life Survey database to more accurately describe congregational activity in the wider community. Items forming the congregational bridging scale include:

-

The congregation has been effectively helping people in the wider community

-

Leaders at church keep attendees strongly focused on connecting with people in the wider community

-

People at church mostly have similar attitudes to actively engaging in community service

-

Involvement of the congregation in other community organizations and events (e.g. community fairs, marches, beautification programmes, Carols by Candlelight)

The first and fourth items focus on the external activity of the congregation while the second and third items focus upon the internal attitudes of the congregation. The third item could potentially register strong agreement where the congregation has mostly negative attitudes to engaging in community service; however, the correlation with the other items showed that respondents interpreted this in terms of positive attitudes to community service.

Congregational Bonding Sub-Scales

Previous analysis (Leonard and Bellamy 2013, forthcoming) using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) identified a single underlying congregational bonding factor, with three primary sub-dimensions, measured by the following sub-scales:

-

Friendships in the congregation: Including the number of close friends who are part of the congregation, ease of making friendships at the congregation, being satisfied with friendships at church, the sense that the congregation is close-knit and a willingness among attendees to go out of their way to help each other (Standardised pathway coefficient = 0.53).

-

Congregational unity: Since personal relationships can also be divisive, data was collected from respondents about perceived congregational divisions, personal experiences of criticism or excessive demands. The resulting scale also included individual responses about trust in people at church and the outcome of any conflict at church (Standardised pathway coefficient = 0.48).

-

Collective efficacy: Respondents provided their perceptions regarding the ability of their congregation’s leaders to bring people together to make things happen, confidence that the congregation would come together to solve serious problems, willingness of the congregation to try new things, the presence of a clear congregational vision for its mission and confidence that the congregation would achieve its vision (Standardised pathway coefficient = 0.83) .

Level of Church Involvement

The level of church involvement was not found to be part of the underlying bonding factor (Leonard and Bellamy 2013, forthcoming). A separate Level of Church Involvement scale was developed comprising frequency of attending services, number of years at the congregation, number of roles in the congregation, involvement in special projects, having a leadership role or being a spokesperson for the congregation.

Motivations for Volunteering in Four Domains and Three Organizational Types

Participants were asked about motivations in four specific domains of volunteering activity, apart from volunteering within a church. The four domains were:

-

Schools

-

Recreation, sport or leisure organizations/groups

-

Community service , care or welfare activities

-

Social action, social justice or lobby groups/activities

For each domain, three types of organizations were distinguished:

-

Organizations associated with a local church

-

Other religious organizations

-

Secular organizations

For each of the four domains, there were six questions regarding the stated reasons for volunteering based on Clary and Snyder’s VFI (1999) and two specifically religious reasons for volunteering. It should be noted that, given the need to cover four domains and the constraints of the survey meant that single items rather than the full VFI scales were used to measure each function. The single items were:

-

To meet the needs of others or to make the world a better place (reflecting VFI values function)

-

To use my skills or to gain more knowledge (reflecting VFI understanding function)

-

To grow more as a person through volunteer activities (reflecting VFI enhancement function)

-

To gain career-related experience (reflecting VFI career function)

-

To meet new people or to spend time with people I know (reflecting VFI social function)

-

To address my own personal needs or problems (reflecting VFI protective function)

-

As part of living out my Christian values or living out my faith

-

As part of God’s mission to the world

For each of these motivations, respondents could indicate that it was the main reason, a very important reason, of some importance or not a reason for me.

To assess the relationship among the religious and VFI items, Exploratory Factor Analyses were conducted for each domain. In each domain, the pattern was the same:

-

The Religious Motivation Factor consisting of the two religious items and the values function item

-

The Personal Motivation Factor consisting of the other five VFI items

Each factor was confirmed using SEM and two scales for each domain were formed with Coef. H > 0.7 indicating strong reliability (Holmes-Smith 2011).

Demographics and Religious Orientation

The survey contained several standard demographic measures including Age , Gender, Highest Education Level and Country of Birth .

Respondents were asked to identify the Denomination of their congregation. They were also asked whether they personally identified with any of several theological streams. Catholicism and Anglo-Catholicism are major theological streams in the Australian context, with Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism being two other major streams. In contrast to these theologically conservative streams, Liberalism is another significant stream. These streams tend to cut across denominational boundaries and are often influential in many denominations.

Analysis

-

1.

Volunteering as an individual in the community was analysed using correlations and a regression analysis with the individual volunteering scale as the dependent variable and age, gender, education, denomination, theological orientation, levels of congregational involvement and congregational bonding as the independent variables.

-

2.

Congregational bridging to the community was analysed using correlations and a regression analysis with the congregational bridging scale as the dependent variable and age, gender, education, denomination, theological orientation, levels of congregational involvement and congregational bonding as the independent variables.

-

3.

Reasons for volunteering in the wider community by type of organization (local church, other religious, secular) was assessed through four repeated measures linear models, one for each domain (school, sport/ recreation, welfare, social action) with the two composite volunteer motivations (Religious and Personal) as dependent variables and type of organization as the independent variable.

Findings

Correlates of Individual Volunteering and Congregational Bridging

It was noted in the Method section that most respondents in this sample have a voluntary role of some kind within their congregation. In addition to this, the vast majority (96 %) had participated in the activities of at least one wider community organization outside of their local church in the past couple of years, while 82 % indicated that they had undertaken other types of volunteer work apart from volunteer roles in their congregation.

Among various demographic characteristics, a person’s highest education level (r = 0.10; p < 0.001) and being born overseas in a non-English-speaking country (r = −0.07; p < 0.01) are weakly but significantly correlated with the Individual Volunteering in the Community scale used in this research.

The church attendees in this sample come from a wide range of theological and denominational backgrounds. Table 7.1 shows that self-identified theological orientation and the denomination of the respondent’s congregation are weakly related or unrelated to both individual volunteering levels and congregational bridging to the wider community. An exception to this finding is being involved with the Uniting Church, which is positively and significantly correlated with individual volunteering. However, being involved with other Protestant denominations (as a single grouping) was negatively but weakly correlated with individual volunteering levels.

Whilst Table 7.1 shows that very little individual volunteering behaviour in the wider community is explained by theological and denominational background, Table 7.2 shows that friendships, unity and collective efficacy—all of which are central to bonding social capital—are also either weakly related or unrelated to individual volunteering in the community. The negative correlation with bonding as unity suggests that situations of congregational disunity may also be a catalyst for some attendees choosing to increase their volunteer involvement with other organizations. It could also be that with increasing unity in the congregation, individual focus and satisfaction are more firmly found in the congregation itself, meaning that volunteering outside the congregation becomes a less attractive option. This interpretation, however, is tempered by the much stronger positive correlation between an individual’s involvement level in the congregation, which includes both volunteering at church and frequency of attendance, and individual volunteering in the community. This suggests that attendees who are highly involved in their local congregations are not doing so at the expense of volunteering in other community organizations; rather a church involvement may well motivate attendees to also volunteer elsewhere.

However, Table 7.2 also shows that the picture is very different when it comes to congregational-level bridging to the wider community. Here all congregational bonding measures are correlated positively and strongly or moderately with congregational bridging to the wider community. The strongest association is between bonding as collective efficacy, or the sense that together we can achieve things, and congregational bridging. A moderate correlation also exists with bonding in the form of friendships.

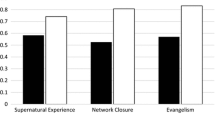

Predictors of Congregational Bridging to the Community

Regression analysis was carried out to identify the key predictors of congregational bridging, the results of which are shown in Table 7.3. Table 7.3 highlights the importance of congregational bonding in predicting congregational bridging. Collective efficacy in particular predicts a large part of the variance in congregational bridging (Beta = 0.54), with some 38 % of the variance in congregational bridging being predicted overall. The strength of friendships within congregations (Beta = 0.14) and being involved in the Uniting Church (Beta = 0.11) also made positive contributions to the model, whilst involvement level in the congregation and having an Evangelical or Reformed faith made smaller negative contributions.

Predictors of Individual Volunteering

In keeping with previous Australian research (Leonard and Bellamy 2010; Lyons and Nivison-Smith 2006), Table 7.4 shows that an individual’s congregational involvement level, which includes both volunteering at church and frequency of attendance, was the most significant predictor of individual volunteering in the community (Beta = 0.38) . It is notable that aspects of congregational bonding generally do not feature in the model, with the exception of bonding as unity, which makes a small negative contribution (Beta = −0.06). This relative lack of contribution by congregational bonding provides some support for Lyons and Nivison-Smith’s (2006) position that there are church attendees who are committed to volunteer across a range of contexts, irrespective of the impact of the social networks within their congregations.

Demographics, such as highest education level and increasing age , also make an independent, positive contribution to the model, while being born in a non-English-speaking country makes a small negative contribution (Beta = −0.06). These results highlight the positive effects of education in providing both vision and skills for volunteer work, while the positive contribution of increasing age is consistent with the greater likelihood of volunteering among middle aged and older people in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010). The negative contribution of country of birth may reflect barriers to do with English language literacy and relative opportunity for wider community participation among migrant groups .

Furthermore, Table 7.4 shows that personal beliefs also have a small independent impact, with particular theological orientations being present in the model—a traditional approach to faith making a positive contribution to predicting individual volunteering (Beta = 0.06) and a Charismatic theological orientation making a negative contribution (Beta = −0.07).

Motivations for Volunteering

Motivations to volunteer beyond the congregation were explored for four domains; schools, sport, recreation or leisure organizations, community service or welfare organizations and social action, justice or lobby groups. Participants were able to respond for any or all the domains and, in the past 2 years, 82 % had volunteered in at least one domain and 11 % had volunteered in all four.

In these four domains, altruistic reasons and religious reasons were the most commonly stated reasons for their volunteering activity. Table 7.5 shows that for each of the four volunteering domains investigated, ‘meeting the needs of others’, was the most frequently stated reason for volunteering. This was closely followed by ‘living out Christian values or faith’ and volunteering ‘as part of God’s mission to the world. Reasons to do with personal growth and the use of skills were the next most common reasons across the four volunteering domains. The least frequently reported reasons were those to do with the meeting of personal needs through volunteering, such as career enhancement and addressing one’s own personal problems or needs.

As described in the Method section, these eight motivations factored into two clear strong factors: a Religious Motivations factor which included the religious motivations and meeting the needs of others and a Personal Motivations factor which included the other listed motivations. These two factors were then used to explore how motivation varied with the type of organization in which the volunteering occurred: the local church, a denominational agency or other religious organization or a non-religious (secular) organization.

Table 7.6 shows the means for the two motivation scales for each domain by type of organization. First, as expected from the table of the separate motivations, religious motivations are stronger than personal motivations for all domains. (F values: school = 607.9, sport/recreation = 424.6, community service = 2,392.9, social action = 1,005.7. All F values were significant at p < 0.0005.)

For type of organization, however, there was a difference between the school domain and the other three domains. For schools, there were no substantial variations in motivation based on the type of organization (For the effect of organization F = 0.6 NS and for the interaction with the motivation scales F = 1.4 NS). However, religious reasons for volunteering were less likely to be given when the organization was a secular sport, recreation or leisure organization, a secular community service or welfare organization or a secular social action, justice or lobby group. (F values for the interaction of type of organisation and motivation scales: sport/recreation = 83.6; community service = 68.3; social action = 36.1. All F values were significant at p < 0.0005.)

The overall picture here is that, no matter the domain for the volunteering, church attendees say that they mostly volunteer out of love for God and love of neighbour rather than for reasons of personal interest. Further, although religious reasons still remained prominent for doing volunteer work even within secular organizations , it appears that for some church attendees the connection between their volunteer work and their faith was less clear when the volunteering was done for a secular organization or group other than a school. While it is unclear why the religious motivation remains strong for volunteering in schools irrespective of the type of organization, part of the reason is likely to be the teaching of religious instruction by volunteers in public schools in Australia.

Discussion

Individual Volunteering in the Community

Based on respondents’ reports of their volunteering activities, the level of involvement of the attendees in their congregations emerged as the strongest predictor of individual volunteering in the community. This finding is in keeping with previous Australian research and echoes the findings of Putnam and Campbell’s study of religion in the USA (2010). They found that religiosity was influential on various forms of civic engagement such as volunteering, not through the beliefs and values of the churches, but rather through the impact of religious social networks within churches. In this respect, they identified close friendships at church, the frequency of discussing religion with family and friends and involvement in small Bible study groups as being key drivers of various forms of civic engagement (Putnam and Campbell 2010, p. 472). However, the findings of the current study suggest that the situation in Australia may be different to that of the USA. It is notable that congregational bonding expressed as friendships did not emerge in this study as a predictor of individual volunteering in the community. Further, the attendee’s involvement in small groups was not strongly correlated with individual volunteering in the community (r = 0.11; p < 0.001). The lack of strong, positive associations between various aspects of congregational bonding and individual volunteering weakens the notion that religious social networks are key drivers of such activity in Australia. The different patterns between Australia and the USA may be explained by the relatively lower levels of church attendance in Australia, leading to a stronger correlation between believing and belonging. By comparison, Putnam and Campbell refer to the ‘imperfect correlation’ in the USA, both with significant numbers of believers outside the churches and non-believers within the churches (Putnam and Campbell 2010, p. 473).

Collective Efficacy and Congregational Bridging

An important distinction emerges in the current study between respondents’ reports of their individual activity (individual volunteering in the community) and their perceptions of collective involvement by the congregation as a whole (congregational bridging to the community) . Whilst religious beliefs and outlook appear to be important to individual volunteering, it is the social dimension that appears to play a stronger role in congregational-level activity. Both individual volunteering and congregational activity have the potential to contribute in positive ways to the social capital of the community. But the way in which each is to be promoted appears to differ greatly, given the very different sets of predictor variables.

The findings about the importance of collective efficacy give an important clue about how congregations can stimulate volunteering, by raising questions about the focus of a congregation: Does it have goals and does it achieve them? Collective efficacy and similar concepts such as collective agency or collective action have been canvassed in the social capital literature (Onyx and Bullen 2000; Leonard and Onyx 2003; Sampson 2006; Staveren and Knorringa 2007) providing a dynamic quality missing from conventional thinking about social capital. More recently Williams and Guerra (2011) noted the importance of collective efficacy and argued that social networks are a necessary precursor for collective mobilisation for the common good. However, rather than a simple causal relationship, it is possible that collective efficacy and congregational bridging work in a positive cycle in which they enhance each other .

The importance of personal friendships is widely acknowledged in church life, and is seen as necessary and expected in the light of Christian teaching to love one another. However the finding that collective efficacy is a stronger factor than the level of friendships in predicting congregational bridging suggests that the achievement of goals and the pursuit of a vision are key ingredients to a richer congregational life and the production of social capital, apart from how attendees treat one another. The current research brings direction and achievement back into the spotlight. Implicit in these findings is the suggestion that congregations should not shy away from the change that would be required in pursuing a vision but should embrace it as part of building social capital both in the wider community and potentially within the congregation .

Previous analysis of the National Church Life Survey data of Anglican and Protestant church attendees in Australia has also pointed to the importance of congregations having a vision for the growth of the church and its members, which is both clearly understood and owned by the congregation itself. This facet of congregational life, which forms part of collective efficacy, has been found previously to not only predict church attendance growth but is strongly linked to attendees’ own sense of belonging to the congregation (Kaldor et al. 1997, p. 141). Commitment to a vision was found to be one of the most important predictors of a sense of belonging to a congregation, along with other aspects of collective efficacy such as a belief that the leaders are capable of achieving goals and that they place a great emphasis on helping attendees to discover their own gifts and skills. The current research elaborates these previous findings by showing the framing of a vision to be part of a greater collective efficacy that needs to be fostered. It means chiefly that congregations need to believe that together they can achieve things and that they can trust both their leaders and each other in pursuing such a vision. In this respect, the link between having a sense of belonging to a church and commitment to a vision becomes clearer. The current research suggests a new focus for the development and understanding of social capital within congregations; the dominance of collective efficacy suggests a dynamic concept whereby a congregation is goal-oriented but not at the expense of relationships among the members of the congregation .

The Relationship Between Bonding and Bridging

The current study sheds light on the relationship between bonding and bridging capital, as identified in the context of church congregations. The research shows that the relationship between bonding and bridging is not a simple one and how some studies point to a negative relationship between the two while others point to a positive relationship. The current study shows the relationship to be more nuanced than first thought. Bonding and bridging are quite strongly related where it is congregational bridging activity that is in question. Even then, it is particular aspects of bonding that appear to be more important within church congregations, particularly aspects of collective agency and the strength of friendship networks.

In this respect, the current study complements other studies which find that interactions inside church groups help to explain ties beyond the groups. For instance, based on a 3-year study of Protestant-based volunteering and advocacy projects in the USA, Paul Lichterman (2005) found that bridges can be successfully built where group customs allow for ongoing reflection and critical discussion about the group’s place in the wider community. He found that the nature of a group’s own togetherness will shape the kind of togetherness it will seek to create in the wider community. Bartkowski and Regis (2003) explored how the abundance of bonding capital within congregations can lead to both compassion towards, and judgment of, those outside the congregation and to coordinated service action or the withholding of such action. Cnaan et al. (2002) showed how congregations work both independently and together to provide social services for individuals and neighbourhoods, complementing Government welfare services in the USA.

Religious and Personal Motivations to Volunteer

The results of the current study have shown that in a sample of church attendees, the religious motivation of individuals plays an important role in their volunteering activity in the wider community. Although differences in theological orientation can play some role, it was broader altruistic reasons and religious reasons, such as living out one’s faith and values, or being part of fulfilling God’s mission in the world, which emerged as important for attendees engaging in a variety of volunteering activity in the wider community. More self-oriented motivations, such as seeing volunteering as a way of dealing with personal problems, using personal skills, or for career enhancement, were less likely to be reported among this sample of Australian church attendees than elsewhere (e.g. Hustinx and Lammertyn 2003).

However, it is noted that the nature of the sample, which is skewed towards more committed and older church attendees, will have an influence on these results. The over-representation of older attendees means that this sample would be less likely to cite career enhancement as a reason for volunteering. Similarly, the high rating for religious motivations across all types of volunteering activity may reflect the high levels of commitment among this sample of church attendees. Nevertheless it needs to be recognised that church attendance in Australia is engaged in by a committed minority of the population for largely intrinsic reasons; it is far less likely now than in previous times that people would attend church for reasons of social desirability, status or other extrinsic reasons.

Attendees’ reasons for volunteering are consistent with Putnam and Campbell’s (2010, pp. 463–465) finding about the importance of altruism as a motivation for church-goers and Clary and Snyder’s (1999) ‘values’ motivation. The eight motivations suggested to respondents grouped into two factors; religious reasons and meeting the needs of others grouped together and career enhancement, social and protective functions grouped together in a pattern similar to the two dimensions identified for Australia generally (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001). However, they do not sit comfortably with conceptualising volunteering in terms of Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan 2000), which focuses on individual competence, connection and autonomy . Although volunteering, as a demonstration of shared Christian values, may be a source of connection with others, social connection was not found to be as strong a reason for volunteering among this sample of attendees.

The prominence of religious reasons for volunteering across a range of volunteering domains outside church life, along with the assumed importance of such reasons for volunteering within church life, points to a common set of motivations both for bridging and bonding activity. This provides further evidence of the connection between bridging and bonding social capital in church life, at least in terms of its expression as volunteering activity. Although motivations were only studied in four domains, they covered the most common avenues for volunteering in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010). Further, despite the differences among the domains, (e.g. sport vs. social action) there was a uniformity to the pattern of motivations which suggests that it is likely to be replicated in other domains that were not examined, such as the arts or health services. However, there may be exceptions, such as volunteering for professional associations, which might strongly relate to career motivations.

Respondents reported that religious reasons for doing volunteer work were still prominent even when volunteering for secular organizations . However, it appeared that, for some attendees, the connection between their volunteer work and their faith was less clear when the volunteering was done for a secular organization or group. By comparison, social services provided by religious organizations might have other religious functions and characteristics which are attractive to those who wish to volunteer as an exercise of their faith. Examples of where a religiously run social service may differ from the secular equivalent would include the presence of prayer and Bible reading and the greater likelihood of meeting other religious people, religious conversation and shared meanings, values and culture.

Conclusion

Bringing these findings together, we find support for the importance of a religious outlook and committed belief in the recruitment of volunteers from within churches but add in the importance of the collective efficacy of the congregation. Such collective efficacy has the potential to develop the public activities of the congregation in the wider community. Those activities offer opportunities for volunteering and provide an ideal pathway for recruiting volunteers from the churchgoers who are already volunteering within the congregation and thus have a demonstrable belief in the value of such work.

These insights are presented from the perspective of those church congregations wishing to increase their social capital and contribution to the community. How well such activities are received by a highly secularised Australian society would depend upon their perceived community benefit. While on the one hand, many Australians are cautious about religious belief that is fervent and passionately held, on the other hand, the welfare and advocacy work of church-based agencies is widely respected. There is already a degree of trust in such church-based agencies and this is reflected in levels of donor support and the awarding of Government contracts; church-based charities are among the largest charitable organizations in Australia. It is within this atmosphere of goodwill that church congregations are able to make a contribution.

The current research is significant in view of the importance of churches, both to the education and welfare sectors in Australia and the importance of volunteering particularly to not-for-profit organizations and charities. The research is also theoretically significant in establishing the relationship between bonding and bridging social capital through collective efficacy .

Future research could investigate whether these insights prove useful to secular organizations , the importance of collective efficacy for example, which may be aided by, but not require, a shared religious faith. Nor does it appear to require a homogeneous group. Leonard and Bellamy (2013, forthcoming) found only a very weak relationship between bonding and a preference for a homogeneous group. A shared commitment to any cause may be a sufficient catalyst for collective efficacy but whether it is actualised in bridging might depend on the group’s goals.

References

Abbott, S. (2009). Social capital and health: The problematic roles of social networks and social surveys. Health Sociology Review, 18(3), 297–306.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2001). Voluntary work Australia 2000 (ABS Cat No. 4441.0). Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Voluntary work Australia (ABS Cat No. 4441.0). Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011). Reflecting a nation: Stories from the 2011 census, 2012–2013 (ABS Cat No. 2071.0). Canberra: ABS.

Bartkowski, J. P., & Regis, H. A. (2003). Charitable choices: Religion, race and poverty in the post-welfare era. New York: New York University Press.

Bellamy, J., & Castle, K. (2004). 2001 church attendance estimates (NCLS Occasional Paper 3). Sydney: NCLS Research.

Bellamy, J., & Kaldor, P. (2002). National Church Life Survey initial impressions 2001. Adelaide: Openbook.

Burt, R. (1998). The gender of social capital. Rationality and Society, 10(1), 5–42.

Burt, R. S. (2004). Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), 349–399.

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(5), 156–159.

Cnaan, R. A., Boddie, S. C., Handy, F., Yancey, G., & Schneider, R. (2002). The invisible caring hand: American congregations and the provision of welfare. New York: New York University Press.

Crowe, J. A. (2007). In search of a happy medium: How the structure of interorganizational networks influence community economic development strategies. Social Networks, 29(4), 469–488.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Donoghue, J., & Tranter, B. (2010). Citizenship, civic engagement and property ownership. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 45(4), 493–508.

Edwards, D. (2005). ‘It’s mostly about me’: Reasons why volunteers contribute their time to museums and art museums. Tourism Review International, 9, 21–31.

Evans, M., & Kelley, J. (2004). Australian economy and society 2002: Religion, morality and public policy in international perspective 1984–2002. Sydney: Federation Press.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Holmes-Smith, P. (2011). Structural equation modeling: From fundamentals to advanced topics. Melbourne: SREAMS.

Hughes, P., & Black, A. (2002). The impact of various personal and social characteristics on volunteering. Australian Journal of Volunteering, 7(2), 59–69.

Hustinx, L., & Lammertyn, F. (2003). Collective and reflexive styles of volunteering: A sociological and modernization perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(2), 167–187.

ISSP. (2009). International Social Science Project. Canberra: Australian National University.

Kaldor, P., Bellamy, J., & Powell, R. (1997). Shaping a future. Characteristics of vital congregations. Adelaide: Openbook.

Leonard, R., & Bellamy, J. (2006). Volunteering within and beyond the congregation: A survey of volunteering among Christian church attendees. Australian Journal of Volunteering, 11(2), 16–24.

Leonard, R., & Bellamy, J. (2010). The relationship between bonding and bridging social capital among Christian denominations across Australia. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 20(4), 445–460.

Leonard, R., & Bellamy, J. (2013 forthcoming). Dimensions of bonding social capital in Christian congregations across Australia. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations.

Leonard, R., & Onyx, J. (2003). Networking through loose and strong ties: An Australian qualitative study. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(2), 191–205.

Leonard, R., & Onyx, J. (2004). Social capital and community building. London: Janus.

Lichterman, P. (2005). Elusive togetherness: Church groups trying to bridge America’s divisions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lyons, M., & Nivison-Smith, I. (2006). The relationship between religion and volunteering in Australia. Australian Journal of Volunteering, 11(2), 25–37.

Molina-Morales, F. X., & Martínez-Fernández, M. T. (2010). Social networks: Effects of social capital on firm innovation. Journal of Small Business Management Accounting Research, 48(2), 258–279.

Onyx, J., & Bullen, P. (2000). Measuring social capital in five communities. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 36(1), 23–42.

Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 88–127.

Perry, J., Coursey, D., Brudney, J., & Littlepage, L. (May–June 2008). What drives morally committed citizens? Public Administration Review, 68(3), 445–458.

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24.

Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. (2002). Democracies in flux. The evolution of social capital in contemporary societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Putnam, R., & Campbell, D. E. (2010). American grace: How religion divides and unites us. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rostila, M. (2010). The facets of social capital. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 41(3), 308–326.

Sampson, R. J. (2006). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In F. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Shye, S. (2010). The motivation to volunteer: A systemic quality of life theory. Social Indicators Research, 98, 183–200. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9545-3.

van Staveren, I., & Knorringa, P. (2007). Unpacking social capital in economic development: How social relations matter. Review of Social Economy, 65(1), 1–9.

Williams, K., & Guerra, N. (2011). Perceptions of collective efficacy and bullying perpetration in schools. Social Problems, 58(1), 126–143.

Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital: Implications for development theory, research and policy. World Bank Research Observer, 15(2), 225–249.

Wuthnow, R. (2004). Saving America? Faith based services and the future of civil society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Yeung, A. B. (2004). An intricate triangle—religiosity, volunteering and social capital: The European perspective, the case of Finland. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(3), 401–422.

Acknowledgments

The research which is the focus of this chapter was funded through an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Projects grant. The research was conducted jointly by the University of Western Sydney and NCLS Research, a research group sponsored by Anglicare Diocese of Sydney, Uniting Mission & Education (Synod of NSW & the ACT), the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference and the Australian Catholic University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bellamy, J., Leonard, R. (2015). Volunteering Among Church Attendees in Australia. In: Hustinx, L., von Essen, J., Haers, J., Mels, S. (eds) Religion and Volunteering. Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04585-6_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04585-6_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-04584-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-04585-6

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)