Abstract

Esophageal diseases are functional disorders (gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), achalasia, esophageal diverticula), congenital abnormalities (esophageal duplication cyst), or tumors (leiomyoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), cancer). In the evaluation of these disorders, no single test provides all the needed information, but the final diagnosis and treatment plan are based on information provided by multiple tests. For instance, in patients with GERD, a barium swallow describes the anatomy of the esophagus and stomach (hiatal hernia, Schatzki’s ring, stricture); an upper endoscopy determines if mucosal injury is present and excludes gastric and duodenal pathology; esophageal manometry defines pressure, length, and position of the lower esophageal sphincter; quality of esophageal peristalsis; and pressure of the upper esophageal sphincter and its coordination with the pharyngeal contraction; ambulatory pH monitoring determines if abnormal gastroesophageal reflux is present, if reflux extends to the proximal esophagus and pharynx, and if there is a temporal correlation between episodes of reflux and symptoms experienced by the patient.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Barium swallow

- Computerized tomography (CT scan)

- Positive emission tomography (PET)

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Hiatal hernia

- Achalasia

- Diffuse esophageal spam

- Zenker’s diverticulum

- Epiphrenic diverticulum

- Esophageal leiomyoma

- Esophageal cancer

Introduction

Esophageal diseases are functional disorders (gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), achalasia, esophageal diverticula), congenital abnormalities (esophageal duplication cyst), or tumors (leiomyoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), cancer). In the evaluation of these disorders, no single test provides all the needed information, but the final diagnosis and treatment plan are based on information provided by multiple tests. For instance, in patients with GERD, a barium swallow describes the anatomy of the esophagus and stomach (hiatal hernia, Schatzki’s ring, stricture); an upper endoscopy determines if mucosal injury is present and excludes gastric and duodenal pathology; esophageal manometry defines pressure, length, and position of the lower esophageal sphincter; quality of esophageal peristalsis; and pressure of the upper esophageal sphincter and its coordination with the pharyngeal contraction; ambulatory pH monitoring determines if abnormal gastroesophageal reflux is present, if reflux extends to the proximal esophagus and pharynx, and if there is a temporal correlation between episodes of reflux and symptoms experienced by the patient. In patients with esophageal cancer, an endoscopy with biopsies establishes the diagnosis; a barium swallow determines the location and length of the cancer; an endoscopic ultrasound, a CT scan, and a PET scan determine the stage of the disease at the time of presentation.

The following chapter illustrates each disease through radiologic images, correlating those with the findings of other tests.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

A barium swallow is a key test for physicians treating patients with GERD. It is the best test to assess the anatomy of the esophagus, the gastroesophageal junction, and the stomach. Some authors feel that this test is also useful for establishing the diagnosis of GERD. Specifically they feel that GERD is present if reflux is demonstrated during the test. However, in a recent study from the University of Chicago, Bello and colleagues tested this hypothesis and reached the opposite conclusion. Specifically they showed that even when reflux is demonstrated during a barium swallow, it does not mean that abnormal reflux will be found on an ambulatory pH monitoring, the gold standard for the diagnosis of GERD. In their study, a cohort of 134 patients underwent barium swallow and pH monitoring. Based on the results of the pH monitoring, they were divided in two groups: GERD + and GERD-. On barium esophagography, gastroesophageal reflux was identified in 47 % of patients in the GERD + group and in 30 % of the GERD-, while no reflux was noted in 53 % of GERD + patients and in 70 % of GERD- patients (p = 0.050), accounting for a sensitivity of 47 %, a specificity of 70 %, a positive predictive value of 68.5 %, and a negative predictive value of 49 %. The overall accuracy was 57 %. In addition, there was no difference in the presence of hiatal hernia between GERD + and GERD- patients (40 % vs. 32 % (p = 0.368)). Similarly, Chen and colleagues demonstrated radiologic abnormalities in only 30 % of patients with an abnormal pH study. Based on these data, a barium swallow should not be considered a diagnostic test for GERD, but rather a complement to other tests, particularly before antireflux surgery. Its great value is providing anatomic information, such as the presence and type of a hiatal hernia, a Schatzki’s ring, or a stricture.

Hiatal Hernia

The hernias of the esophageal hiatus are divided in four types (I, II, III, IV):

-

Type I hiatal hernia occurs when the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and the upper stomach are herniated into the chest. The GEJ maintains its position above the herniated stomach (Figs. 2.1 and 2.2). It is also called “sliding” hiatal hernia as it can slide in and out of the thoracic cavity so that the presence and size of the hernia can vary over time. This is the most common type of hernia, accounting for more than 85 % of all hiatal hernias.

-

Type II paraesophageal hiatal hernia. This type of hernia (also known as “rolling hernia) occurs when the stomach rolls in the posterior mediastinum next to the GEJ (usually left lateral) which maintains its normal position (Fig. 2.3).

-

Type III paraesophageal hernia. This is also known as “mixed” hiatal hernia, a combination of sliding and rolling as both the GEJ and the stomach are herniated in the chest, with the stomach located next to the esophagus (Fig. 2.4). These hernias can be very large, and sometimes they can be identified in plain upright chest radiograph (Fig. 2.5). These hernias can be associated with a gastric volvulus (Figs. 2.6 and 2.7).

-

Type IV. These hernias occur when not only the stomach but other upper abdominal organs (colon, spleen, omentum, small bowel) are herniated into the chest (Fig. 2.8).

Schatzki’s Ring

Schatzki’s rings are found at the level of the GEJ or just above it. They consist of annular membranes of mucosa and submucosa, and they are usually associated with pathologic gastroesophageal reflux (Figs. 2.9 and 2.10).

Achalasia

Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder characterized by failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax appropriately in response to swallowing and absent esophageal peristalsis. The classic radiologic findings include a) distal esophageal narrowing (“bird beak”); an air-fluid level, residual food in the esophagus; and slow emptying of the barium from the esophagus into the stomach (Fig. 2.11). In long-standing cases, the esophagus may become dilated and assume a sigmoid shape (Figs. 2.12 and 2.13). These findings are very important as treatment (pneumatic dilatation or surgery) is usually less effective when the esophagus is massively dilated and sigmoid, and an esophageal resection, may be indicated.

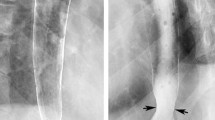

Diffuse esophageal spasm (DES) is another esophageal motility disorder, less frequent than achalasia. In DES the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter may be normal or elevated, and normal peristalsis is mixed with simultaneous contractions. This disorder is often intermittent so that the esophagus can sometimes look normal while other times shows the characteristic “corkscrew” appearance (Figs. 2.14 and 2.15).

Esophageal Diverticula

Zenker’s Diverticulum

This diverticulum forms in the Killian’s triangle, limited superiorly by the inferior constrictors of the pharynx and inferiorly by the cricopharyngeus muscle (Figs. 2.16 and 2.17). A functional obstruction, such as a hypertensive upper esophageal sphincter (UES) or a lack of coordination between the pharyngeal contraction and the UES, probably causes the formation of this diverticulum.

Epiphrenic Diverticulum

This diverticulum is located in the distal esophagus above the diaphragm, more commonly on the right side (Figs. 2.18, 2.19, and 2.20). This diverticulum is usually associated with a primary esophageal motility disorder such as achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm.

Benign Esophageal Tumors

Polyps

Fibrovascular polyps are benign mesenchymal tumors. They usually present as a pedunculated intraluminal mass (Fig. 2.21). They are well diagnosed by endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (Fig. 2.22).

Leiomyomas

They are the most common benign submucosal tumors in the esophagus (Fig. 2.23). They present as an intraluminal defect, and they are well defined by endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (Fig. 2.24).

Malignant Esophageal Tumors

Esophageal Cancer

The squamous cell cancer is usually localized in the mid-thoracic esophagus (Figs. 2.25 and 2.26), while the adenocarcinoma is more frequently located in the distal esophagus arising from a background of Barrett’s esophagus (Figs. 2.27 and 2.28). The diagnosis is established by endoscopy with biopsies. The staging of the cancer relies on endoscopic ultrasound to define the depth of the tumor (T) and the presence of pathologic periesophageal lymph nodes (N) (Fig. 2.29) and on a CT scan (Figs. 2.30, 2.31, and 2.32) and a PET scan to identify distant metastases (Figs. 2.33, and 2.34).

Selected Reading

Allaix ME, Patti MG. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:425–8.

Allaix ME, Herbella FA, Patti MG. The evolution of the treatment of esophageal achalasia: a look at the last two decades. Updates Surg. 2012;64:161–5.

Baker ME, Einstein DM, Herts BR, Remer EM, Motta-Ramirez GA, Ehrenwald E, Rice TW, Richter JE. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: integrating the barium esophagram before and after antireflux surgery. Radiology. 2007;243:329–39.

Bello B, Zoccali M, Gullo R, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and antireflux surgery. What is the proper preoperative work-up? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:14–20.

Bruzzi JF, Munden RF, Truong MT, et al. PET/CT of esophageal cancer: its role in clinical management. Radiographics. 2007;27:1635–52.

Chen MYM, Ott DJ, Sinclair PA, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: correlation of esophageal pH testing and radiographic findings. Radiology. 1992;185:483–6.

Cole TJ, Turner MA. Manifestations of gastrointestinal disease on chest radiographs. Radiographics. 1993;13:1013–34.

Dean C, Etienne D, Carpentier B, et al. Hiatal hernias. Surg Radiol Anat. 2012;34:291–9.

Gullo R, Herbella FA, Patti MG. Laparoscopic excision of esophageal leiomyoma. Updates Surg. 2012;64:315–8.

Hansford BG, Mitchell MT, Gasparaitis A. Water flush technique: a noninvasive method of optimizing visualization of the distal esophagus in patients with primary achalasia. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:818–21.

Herbella FA, Patti MG, Del Grande JC. Hiatal mesh repair—current status. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:61–6.

Jobe BA, Richter JE, Hoppo T, et al. Preoperative diagnostic work up before antireflux surgery: an evidence and experience-based consensus of the esophageal diagnostic advisory panel. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:586–97.

Lee SS, Ha HK, Byun JH, et al. Superficial esophageal cancer: esophagographic findings correlated with histopathologic findings. Radiology. 2005;236:535–44.

Levine MS. Benign tumors of the esophagus. In: Gore RM, Levine MS, editors. Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. Second edition: WB Saunders; 2000.

Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology. 2005;237:414–27.

Levine MS, Chu P, Furth EE, et al. Carcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: sensitivity of radiographic diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1423–6.

Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Barium esophagography: a study for all seasons. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:11–25.

Muller M, Gockel I, Hedwig P, et al. Is the Schatzki ring a unique esophageal entity? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2838–43.

Patel B, Han E, Swan K. Richard Schatzki: a familiar ring. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:678–82.

Patti MG, Herbella FA. Achalasia and other esophageal motility disorders. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:703–7.

Patti MG, Waxman I. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: from heartburn to cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3743–4.

Patti MG, Gorodner MV, Galvani C, et al. Spectrum of esophageal motility disorders: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Arch Surg. 2005;140:442–8.

SAGES Guidelines Committee. Guidelines for the management of hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(12):4409–28.

Soares R, Herbella FA, Prachand VN, Ferguson MK, Patti MG. Epiphrenic diverticulum of the esophagus: from pathophysiology to treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:2009–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Borraez, B.A., Gasparaitis, A., Patti, M.G. (2014). Esophageal Diseases: Radiologic Images. In: Fisichella, P., Allaix, M., Morino, M., Patti, M. (eds) Esophageal Diseases. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04337-1_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04337-1_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-04336-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-04337-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)