Abstract

It is estimated that about one third of the clinical trials conducted in Argentina occur in the province of Cordoba, home to only 10 % of the country’s total population. This chapter describes the evolution of the provincial regulatory framework, the organizational environment that allowed the development of a private research center within the premises of a public hospital, and the ensuing collusion between researchers and clinicians.

Changes of the regulatory system coincide with political changes in the municipal and provincial governments. An investigation unveiled a series of problems including the diversion of public resources, the improper management of ethics committees and protocol approvals, and the use of coercive methods to expedite the recruitment of patients – often without informed consent. When, as a result of the investigation, the researchers were banned from the municipal hospital and health centers the provincial political leaders opened the doors of provincial health facilities, where they continued the implementation of clinical trials. In one instance, they conducted a trial despite the objection of the National Ministry of Justice. Eventually, one principal investigator and the research sponsor were fined for implementing a vaccine trial without informed consent.

This chapter illustrates how the political context can allow financial and power gain to trump ethical and scientific considerations, and how the decentralization of the health sector led to poor collaboration between the national and provincial health authorities.

The authors would like to thank Juan Carlos Tealdi and Susana Vidal for their assistance and comments during the preparation of this chapter. The authors have sole responsibility for analysis and interpretation of the data.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

5.1 The Clinical Trial Regulatory Framework in Cordoba

As explained in Chap. 4, Argentina is a federation of 23 provinces and the autonomous Federal Capital. Each province has its own executive, legislative, and judicial governments. Each province has its own Ministry of Health that is responsible for the regulation of the health sector and the provision of medical care services for the poor.

It is estimated that one third of all clinical trials conducted in the country take place in the Province of Cordoba, which houses about one tenth of the national population (Fernández 2005a). Recognizing this situation, the provincial government initiated the development of standards for clinical research involving humans. In 2001, the bioethics department of the provincial Ministry of Health designed a program for ethics in health research, which included the creation of a Provincial Commission for Ethics in Health Research (COPEIS in Spanish) to develop ethical standards, train professionals in research ethics, establish criteria for accreditation of Institutional Research Ethics Committees (IRECs), create a Provincial Registry for Health Research (RHR), and evaluate research protocols that could threaten the wellbeing of clinical trial participants.

During the first two years (2001 and 2002), almost 200 professionals were trained in five-month classroom courses. The COPEIS started functioning in 2002 as part of a supervision unit of the provincial Ministry of Public Health, a status that gave it legitimacy and sanctioning powers. The beginning of the following year (2003) saw the approval of Ministerial Resolution 729/02, which included the criteria for accreditation of the IRECs and the model for the evaluation of research protocols. Only hospital-based IRECs would be accredited; ethics committees in non-hospital settings, such as those established by foundations or other research centers, would not be accredited in the Province of Cordoba, although they could be accredited in other parts of the country. At the end of 2003, 11 IRECs had been accredited in the Province, and the RHR was operational (Vidal 2006).

Parts of the legislation – including the functions of the COPEIS and the decision to accredit only hospital-based IRECs – was rejected by researchers interested in conducting clinical trials at private centers and foundations, although highly complex private institutions had no problem accommodating to the new regulations (Ministerio de Salud 2006). The disagreement and rejection of these legislative items created difficulties for the staff in the bioethics department who had developed the standards (Ministerio de Salud 2006).

In an attempt to overcome these problems and the pressure from the private centers, the bioethics unit strengthened and increased the trainings for researchers and other personnel, especially those responsible for implementing the regulation and evaluating the clinical trials. Biomedical research institutions and human rights organizations had always been invited to designate representatives to the COPEIS, and information on the relationship between research involving humans and human rights was shared with the public. The promotion of civic participation and democratic inclusion was intended to strengthen the project.

Researchers working in small private centers organized and requested the political authorities of the Province to remove the regulatory aspects that interfered with the implementation of clinical trials. Without consulting either the experts in bioethics of the Provincial Ministry of Health, or the COPEIS, the clause in Resolution 729 requiring submission of clinical trial budgets and financing to the IRECs before the approval of a clinical trial, was suspended – just three months after it had become effective. Specifically, information was no longer required regarding: (1) the detailed research budget (the amount paid by the study sponsor, generally a multinational pharmaceutical company, to the principal investigator and to other researchers and institutions); (2) the compensation promised to the study participants (including expenses and access to medical attention); and (3) where appropriate, the fee to be paid to an institution for the evaluation of the study protocol by its IREC. The economic aspects of clinical trials have an important relationship with ethics and respect for the human rights of the participants, which is not always recognized by researchers, including those in the USA (Barlett and Steele 2011).

In October 2003, the Provincial authorities suspended the activities of the COPEIS, and in November, the agency was eliminated. New standards were published keeping much of the original content, but removing the requirements to: (1) name the place where the clinical trial participants would receive health care and the referral center where they could go in case of need; (2) provide insurance to compensate participants in case of harm attributable to their participation in the clinical trial; (3) describe the mechanisms to ensure access to treatment following the completion of the clinical trial; and (4) provide the budgetary information previously noted - payments to researchers, participants, and institutions. In addition, the new standards allowed accreditation of IRECs in research centers without medical care services.

Instead of the disbanded COPEIS, a Provincial Commission for Research with Human Subjects (CPISH in Spanish) was created. The new Commission consisting of three researchers from the private sector and one expert in bioethics started operations in 2004, but the bioethics expert resigned, soon after, and the Commission continued for some time without a bioethicist, until the position was replaced with a clinical researcher. In a very short time, the new Commission approved 14 IRECs, more than the previous Commission had approved in its two years of existence. Of the 25 approved IRECs, 18 were in private institutions, of which seven were highly complex institutions, five were of medium or low complexity, and six were centers, foundations, institutes, or polyclinics. The remaining seven IRECs were in public institutions, all highly specialized referral centers (Ministerio de Salud 2006).

The Provincial Ministry of Health continued to gather data on the protocols approved by the IRECs, such as the number of participants, the date of completion of the study, and adverse events. The information on the clinical trials authorized in the Province and the institutions where they were implemented became available on the internet, but the training program established by the old Commission was suspended.

Also in 2004, the researchers opposed to Resolution 729 established the Clinical Research Society of Cordoba (SICC in Spanish) in the city of Cordoba, which has been joined by many clinics, health centers, institutes, foundations, and private, and some public, hospitals. Little information about their activities is available on their web page: (http://www.sicc.org.ar/sicc/index.php).

In 2010, the SICC, together with the Argentine Chamber of Clinical Research Organizations (CAOIC in Spanish), organized a modular program for training and certification in clinical research. The first module of the program, a one-day intensive course, took place in December 2010, with almost 100 researchers in attendance. This is the only activity mentioned on the Society's web page, suggesting that it functions primarily as a pressure group. Training in clinical research – in this case, clinical trials outside the academic environment and in private institutions with economic connections to the pharmaceutical industry – might be tainted with conflicts of interests.

An investigative journalist, reviewing the minutes of the CPISH, identified conflicts of interest in almost half of the 78 meetings held by the Commission during 2005. A substantial number of evaluators had conflicts of interest and could not participate in meetings, which had consequences. In some cases protocol approvals were granted in the absence of quorum, and with the presence of only one or two persons (Fernández 2005b).

Following the appointment of a new Provincial Minister of Health towards the end of 2006, the Ministerial Resolution 493/2006 was passed, leading to the suspension of the CPISH. The authorization of clinical trials did not resume until January 17, 2007. In an interview with the press, the Minister said (Fernández 2006):

There is a huge number of research proposals in the review process, and we prefer to wait until the new standards are ready. Approvals had been granted at a rate of three to four protocols per week [meaning that previously the protocols had been reviewed too expeditiously]

When all the members of the Commission were asked to resign, the Minister temporarily assumed its functions. According to statements to the press, this was necessary to avoid possible conflicts of interest – a criticism raised against former Commission members, all of whom were clinical researchers. Resolution 22/07, published on January 24, 2007, provided the new standards for biomedical research involving humans (Boletín Oficial 2007), which aimed at increasing transparency and avoiding conflicts of interest during the clinical trial approval process. Referring to criticisms (see below), the Minister said (Fernández 2006):

We do not want to recruit patients in the public sector for studies that will be conducted in the private sector

Regulation 22/07 rescinded several clauses introduced by the previous Minister, revived others included in Resolution 729 that had generated opposition, and added a few new clauses. The CPISH was replaced by the Health Research Ethics Review Board (COIES in Spanish), which remains the governing body for clinical trials. Much of Resolution 22/07 discusses the IRECs, and mandates the inclusion of five permanent members: one with experience in research, another with experience in bioethics, a community representative, a non-physician health professional, and a legal advisor. The composition of the new IREC is very different from its predecessor, and, if needed, the IRECs can invite specialists to provide expert opinions.

For clinical trials to be conducted in the public sector, Resolution 22/07 established three IRECs: one for clinical trials in maternal-child health (probably in response to a situation which will be presented later in this chapter), another for clinical trials related to mental health, and the third for all other protocols. The IRECs were given clear responsibility for all necessary follow-up during the implementation of the clinical trials.

Collecting a percentage of the proposed research budget from researchers or sponsors was one innovation introduced by Resolution 22/07. The percentage differed for public and private institutions. The funds raised would cover the costs of monitoring the study, and other items such as the Provincial Registry of Health Research.

Annex III of the resolution indicates that the requests for protocol evaluation had to include a fee to be paid to the institution of the IREC that would be conducting the evaluation. It did not establish the method to determine the amount of the fee, nor did it state allocation of the fee to the different tasks.

The exclusion of institutions without medical care services was reinstated. However, a few months later it was amended. Specialized private institutions without medical care services could request an exception and be allowed to establish an IREC (Gobierno de Córdoba 2007):

… to evaluate and control only ambulatory studies related to the specialty of the health facility

The new amendment also required indemnity insurance in case of disability or death caused by participation in the clinical trial.

Resolution 22/07 did not require a detailed budget for the proposed clinical trial, only a declaration from the principal investigator showing the compensations payable to the participants for their expenses and for necessary medical attention. Only healthy participants could receive payment.

5.2 Clinical Trials in the Children’s Hospital of the Municipality of Cordoba

The medical facilities of the Municipality of Cordoba, which serve the poor and the indigent, have been used to recruit and conduct clinical trials since 1987. The Municipal Children’s Hospital is a high technology hospital and serves as referral center for many primary care centers (Ávila Vázquez 2007).

According to the National Administration of Food, Drugs and Medical Technology (ANMAT in Spanish), between 1996 and 2003, 19 clinical trials were conducted at the Children’s Hospital, and the Chief of the Department of Pediatrics, who supervised 50 pediatric residents, was listed as principal investigator for 16 of the 19 studies (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2006).

Most of these studies were Phase III trials of vaccines, antibiotics, antihypertensives and asthma medications for children, and were sponsored by SmithKlineBeecham, Merck, Sharp & Dome, Upjohn, and Aventis, among others (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2007). ANMAT did not share information on the results of the trials, serious adverse events and deaths, or agreements between the principal investigator and the sponsors of these studies with the Municipality (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2006). ANMAT did not provide information about the number of trial participants to be recruited in the province, but information collected from municipal institutions indicated that 2,200 children were participating in the trials directed by the Chief of Pediatrics (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2007:4). Ávila Vázquez (2007) estimated that the researchers could have received between US$500 and US$12,000 per patient recruited, and the total amount collected by the researchers could be up to US$ 24 million. Most of these studies took place through the Center for Studies for the Development of Advanced Projects in Pediatrics (CEDPAP in Spanish), a private organization (CRO) directed by the Chief of Pediatrics of the Children Municipal Hospital, who implemented clinical trials in this hospital and in other public sector facilities.

In 1998, CEDPAP signed a three-year contract with the Municipality of Cordoba. The contract was for the surveillance of pneumococcus infections and read (Sarasqueta 2004:34):

… given its future importance for the development of interventions to reduce respiratory infections in children all departments of the Ministry of Public Health and Environment of the Municipality of Cordoba are authorized to participate in this project…

CEDPAP’s interest in preparing the ground for future vaccine trials was clear from the language included in the contract.

CEDPAP’s administrative offices were located inside the Children’s Hospital until 2001. The fact that the Department of Pediatrics and CEDPAP were headed by the same physician, had the same postal address and all documents related to the clinical trials had the logos of the two institutions was a cause of confusion; and hospital staff and outside researchers worked side by side. Hospital staff resented the fact the clinical trials benefitted businesses, and the public hospital was not compensated for the use of supplies and human resources. However, it was not until 2006 that CEDPAP’s director was prosecuted for allowing a private business to benefit from the resources of a public hospital.

After the CEDPAP offices were moved from the Hospital, the clinical trials continued to be conducted inside the hospital, and the relationship between the hospital and CEDPAP was well explained by the hospital’s director in a memorandum to the Directors of the Departments of Pediatrics, Surgery and Diagnosis and Treatment, where he stated that CEDPAP would continue to be the “Research Branch of our hospital” (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2006:4).

The Chief of Pediatrics continued implementing clinical trials in the municipal hospital after the three-years contract expired. During his work as principal investigator of clinical trials, he achieved prestige among his peers and the recognition of international institutions, allowing him to establish connections with provincial and national politicians. CEDPAP also gained recognition, and signed contracts with Argentinean universities and municipalities to carry out other research projects.

In 2003, two years after the expiration of the contract, CEDPAP signed a Cooperation Agreement with the Municipality of Cordoba. The Annex to the Agreement clarified that CEDPAP wanted to conduct clinical trials sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry.

Almost immediately, CEDPAP’s activities started to be questioned. Complaints were heard from physicians in neighborhood health centers, which served a very low income population and were within the catchment area of the Children’s Hospital. In response to criticisms raised by people with some knowledge of the situation, several agencies and organizations, including the Social Services area of the Catholic Church, the Medical Council of the Province of Cordoba and the Public Ombudsman, requested the municipal authorities to investigate (2006).

The Trade Union of Workers and Municipal Employees opposed the permission to meddle in the affairs of the municipal health facilities granted by the Agreement to CEDPAP, a private company, for the benefit of the pharmaceutical industry. This was the final straw, and the Cooperation Agreement between the Municipality and CEDPAP was annulled a few days after it had been signed (Franco 2006).

With the election of a new municipal government, the Municipality of Cordoba began an investigation of the Children’s Hospital at the end of 2003, suspending all clinical research in the municipality. The Department of Human Rights in the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights asked Dr. Pedro Sarasqueta, Chief of the Neonatology Service in the Garraham Hospital, Buenos Aires, to prepare an Expert Report,Footnote 1 including an analysis of all the documents and complaints collected on the situation at the Children’s Hospital. Dr. Sarasqueta said in conclusions of his Report (Sarasqueta 2004):

-

1.

The hospital had not estimated the cost of the supplies used, and did not compare the cost incurred with the benefits obtained from the clinical trials. Statements by hospital personnel indicated that (Sarasqueta 2004:1):

…in some current research, such as the pneumococcus surveillance study, increasing amounts of laboratory and radiological supplies are being used and paid for by the Children’s Hospital of Cordoba, substantially adding to the operating cost of the hospital in these budget lines. Other testimony that will need to be evaluated during the Administrative Inquiry describes situations where essential blood cultures were not done for patients outside the study protocol due to lack of funds in the hospital budget, while those in the study received them because the supplies were provided by the sponsor

-

2.

There was political interference because the study “Hospital-based surveillance to estimate the disease burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children less than three years of age in Cordoba, Argentina” was approved by the Minister of Health more than one month before receiving the scientific and ethical approval of the corresponding committees. And the IREC, which finally approved the study, carried the logos of the two institutions, reflecting the confusion between the Hospital and CEDPAP (Sarasqueta 2004:17)

-

3.

The ethics committee of the hospital that approved the protocol of the anti-pneumococcal vaccine did not comply with existing regulations. The approval document included the name of CEDPAP and the name of the hospital, as well as the names of the principal investigator and co-investigator, who due to conflicts of interests should not be present during the discussion much less vote for the approval of the protocol.

-

4.

The work of the hospital was impacted. As in many municipal hospitals operating with scarce resources, the presence of a number of clinicians who were not part of the hospital staff could (Sarasqueta 2004:22):

…produce a strong institutional imbalance between research and staff physicians with different tasks and very different remunerations, which can result in significant adverse changes in the implementation of the most important functions of public institutions, which is the provision of health care for predominantly low-income populations, whose only health resource are the public hospitals

This is to say, there was differential access to necessary diagnostic tests and treatments: if the patient was a clinical trial participant he/she had preferential access while regular patients did not. There were instances when a clinical trial took place without the knowledge of the hospital staff, implying potential risks for the patient.

Dr Sarasqueta acknowledged that this problem was due in part to the former Municipal Secretary of Health, who allowed a private institution to operate within public health facilities without controls, and without informing “…senior administrators, such as the Director General for Coordination of Primary Care” (Sarasqueta 2004:23).

-

5.

According to information presented in the dossier, the consent to participate in the clinical trial was not always informed. One mother did not understand that her daughter could be in the control group, and might not receive the vaccine. According to her testimony, she (Sarasqueta 2004:24):

…was read only part of the informed consent, which was colored in yellow. She signed the document, then they gave her another part of the document which was white, with several sheets of paper, which she was not able to read before signing the consent

When she asked why her daughter had become ill during the study, she was told that her daughter had received the placebo, a word she did not understand and had to look up in a dictionary.

-

6.

It was not ethical for CEDPAP to pay residents working in a clinical trial, since this was “…a distortion during a time of learning about professional standards” (Sarasqueta 2004 :35). Nor was it considered acceptable to pressure professionals working in municipal facilities to become involved in the clinical trials by collecting information, providing services to clinical trial participants, or recruiting patients. When municipal employees opposed these practices, the Municipal Secretary of Health replied (Sarasqueta 2004:35):

It is the decision of this Secretariat that the issue be resolved and timely notification given to continue the studies with the possibility of imposing sanctions against those professionals employed [by this Secretariat] who do not comply with the directive

The evaluation report confirmed that the Municipal Secretary of Health had ceded power to the private sector for managing research, conducting interventions and providing care in municipal pediatric facilities.

After the Expert Report was received, the Municipal Government began an Administrative Inquiry in 2004 (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2005a). Following interviews with many people, the 364 page document resulting from the investigation confirmed the conclusions of the Expert Report, stating that:

-

Municipal employees had been pressured to contribute to the implementation of clinical trials by recruiting patients under three years of age, drawing blood for tests, giving vaccinations, and performing other activities

-

Informed consents were signed without properly informing parents or witnesses about the study protocol – including that blood samples were to be sent to another country – or explaining the risks assumed by participating in an experimental vaccine trial

-

The protocol had been approved by an Ethics Committee which included the researchers

-

Physicians, biochemists, radiologists, laboratory technicians, and nurses had been pressured, through monetary compensation or by management, to recruit the number of participants required by the protocol

-

To comply with the study protocol, CEDPAP personnel worked in the Hospital and in clinics within its catchment area; they unlawfully gained access to medical records and classified documents, and made illegible notes that the hospital staff, who cared for patients prior to their enrollment in the trials could not understand; and

-

CEDPAP physicians did not know how to treat adverse effects or they had been forbidden to do so

The document also stated that equipment donated to the hospital had disappeared, a situation that was reported to the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor.

Based on these and other charges, which are detailed in the document, and for reasons of space, are omitted, 12 municipal employees were disciplined for non-compliance with municipal ordinances. Of these 12, four were dismissed and eight suspended for 15 or 30 days (Municipalidad de Córdoba 2005b). The Chief of Pediatrics escaped sanctions as he reached retirement age and chose to retire.

One of the dismissed employees appealed the dismissal and received a majority decision for reinstatement. In addition, the municipality had to pay lost wages and a US$3,700 compensation for unjust dismissal (Cámara Contencioso Administrativo de Primera Nominación 2009). The trial judges did not discuss the possible ethical violations committed in the clinical trials, but explained why the employee should be reinstated. In their opinion, the administrative sanction was excessive. They questioned the reasons for not applying the same sanction to everyone involved in the clinical trials, and said that pressure from senior hospital personnel had caused the employee's actions.

The remaining cases were also acquitted (La Mañana de Córdoba 2009), and the Mayor, in his new electoral campaign, publically apologized to the Chief of Pediatrics, perhaps in response to the Chief’s lawsuits against the Mayor, the Deputy Mayor, the Municipal Secretary and Sub-Secretary of Health, the Municipal Director of Medical Care, the ex-Director of the Hospital, and other physicians and union members. The grounds for the lawsuits were that when the municipal authorities discontinued the epidemiological surveillance in the region, they violated Article 205 of the Penal Code, which stated that it was an offense (Franco 2005):

…to contravene the measures adopted by appropriate authorities to prevent the introduction or propagation of an epidemic.

In the Complaint filed by the Chief of Pediatrics, there were few references to the clinical trials and the alleged ethical violations, which were the foundation of the preliminary investigation (Franco 2005).

According to the Chief of Pediatrics, infant mortality had increased in the Municipality of Cordoba because the new administration had prevented the continuation of the epidemiological surveillance approved by previous authorities, which CEDPAP had been conducting without using public funds. There was no mention that the epidemiological surveillance was funded by a pharmaceutical company (in this case, by GSK, which was presumably financing this study to gather information for the development of vaccines). The Complaint stated that the Administrative Inquiry was a conspiracy against the Chief of Pediatrics (Franco 2005):

At no time was there any intent to ‘investigate’ anything, only to find something to legitimize what had been previously decided: to eliminate Dr. Tregnaghi, his team, and all the scientific projects they were conducting

The Complaint added that the personal attack was a political decision, evidenced by the appointment of a Chief Investigator who “had a well-recognized feud” against him (Mac Lean and Degiorgis 2005).

The Chief of Pediatrics was charged with theft, but due to the statute of limitations (two years) the charge was dismissed. In his Complaint, he stated that he had reported the theft of equipment donated by GSK at his request, to the administration of the Children’s Hospital.

Two former Chiefs of Residents in the Children’s Hospital (2001–2002 and 2004–2005) made statements about the ‘scientific nature’ of the clinical trials. According to them, the function of the Argentine researchers was limited to collecting data and caring for patients (Mac Lean and Degiorgis 2005). And they noted that in Cordoba (Mac Lean and Degiorgis 2005:1):

… after many years of scientific work in the Hospital, we should find a reliable practice of research or a scientific culture, which isn’t there

They concluded that it could not be said that in Cordoba there was a clinical scientific community, but that there was a commercial activity of clinical trials in public hospitals that was used for private gain. One of the commercial products was a vaccine marketed by a foreign company and sold at a price outside the reach of the impoverished clinical trial participants.

… Monetary payment was the principal stimulus for the hospital residents, noting that most did not receive a salary… [but] were even coerced by the Chief of Pediatrics… For years, the Chief of Pediatrics and head of CEDPAP paid US$20 to the resident on duty who found pneumonia on an X-ray, and the payment increased to US$50 if pneumococcus was found in the blood culture, and we do not think that this is the way to make science (Mac Lean and Degiorgis 2005:1)

5.3 Two Case Studies: COMPAS and the Hepatitis Vaccine Trials

5.3.1 The COMPAS Trial

Upon retirement, the Chief of Pediatrics ceased to work for the municipality, and since the Mayor had suspended his research, he could no longer use the Municipal Children’s Hospital for his clinical trials. The clinical trials continued, however, because the Provincial Minister of Health welcomed the retired Chief, offered him the use of the Provincial Maternal-Neonatal Hospital and other provincial facilities, and made arrangements for his research to continue in other municipalities of the Province. In addition, in 2003, the Provincial Minister made the regulatory changes to Resolution 729, previously discussed.

The retired Chief of Pediatrics looked for other municipalities in Cordoba and in other provinces (see Chap. 4) to carry out the clinical trial of a GSK vaccine to prevent pneumococcal infections – known as the COMPAS trial. The COMPAS trial was an international, multicenter trial that in the Latin American region included Panama, Colombia and Argentina, where they expected to enroll 24,000 children under one year of age. Argentina had the highest quota of 17,000 children, but recruitment was halted at 13,981.

With the support of the Provincial Ministry of Health, the city of Rio Cuarto in the municipality of the same name was chosen for the trial. Rio Cuarto has a population of 166,000 (2010) and is a service town for the rural communities of the municipality. At the beginning, only a few municipal clinics participated in the trial, but in 2005, all municipal clinics recruited children for the trial and a total of 331 babies were enrolled (Puntual 2005).

The Provincial Deputy Minister of Health said that the mothers of the children had received a detailed explanation of the nature of the clinical trial, and had to consent before their children could participate. He added that the vaccine had no risks for the children, that it was safe, and that all physicians of the municipality would be trained as “assistant researchers”. Since the clinical trial was taking place in municipal facilities, and municipal personnel would be assistant researchers, it is probable that the municipality incurred some expenses; however, the amounts, spent, and the compensation offered by GSK are unknown. As explained in Chap. 4, the informed consent was poorly understood by mothers, and a few children enrolled in the trial in other provinces, died.

The Deputy Minister said (Orchuela 2006):

Recently, in compliance with the protocol, we have been congratulated for the timely enrolment of more than 300 children

which unveils the interest of the provincial authorities in satisfying the speedy recruitment that multinationals demand from clinical trial researchers.Footnote 2 In 2009, as mentioned in Chap. 4, the principal investigator and GSK were fined by ANMAT for not complying with clinical trial guidelines during the implementation of COMPAS.

5.3.2 Phase II Study of the Immunogenicity of a Vaccine

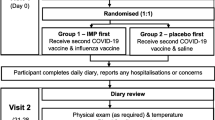

According to clinicaltrials.gov, the purpose of the Sanofi-Aventis sponsored Phase II study comparing the immunogenicity of the combined DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP-T vaccine with Pentaxim and Engerix-B Pediatric vaccines in healthy Argentine children at 2, 4, & 6 months of age was “to demonstrate that the immune response in the month of receiving the three doses of the hexavalent vaccine (DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP-T) is not inferior to that generated after receiving the corresponding doses of the association of Pentaxim and Engerix-B Pediatric.” The secondary objective of this clinical trial was to describe the safety profile of the vaccines in the two groups.

The study was conducted by CEDPAP and the physicians of the Provincial Maternal Neonatal Hospital in Cordoba, with the approval of ANMAT and the Ministry of Health of the Province of Cordoba.

According to clinicaltrials.gov, the enrollment of 624 children in Cordoba began in October 2004 and ended in November 2005; despite the fact that the Council on Bioethics and Human Rights in Biomedical Research at the National Ministry of Justice announced in July, 2005, that (Tealdi 2005:13):

… implementation should not be approved. If the study has started, it must be suspended with due care for the protection of research subjects

In Argentina, the National Ministry of Justice is obliged to investigate citizen complaints involving human rights violations and the number of petitions has increased in recent years.

The national Ministry of Justice issued a lengthy report, which included the following points: (1) the implementation of the study disrupted the national calendar for vaccinations, put children at risk, and, being a study aimed at changing public policy, it was approved without an analysis of its relevance and possible impact on the public health of the nation; (2) there were conflicts of interest in the ethics committee that approved the study; and (3) the study was approved by the ethics committee although it violated nine paragraphs of the Declaration of Helsinki and ten clauses of the Guidelines issued by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences and the World Health Organization -CIOMS/WHO 2002.

The official immunizations calendar of Argentina requires the administration of the first dose of the Hepatitis B vaccine at birth, while the research protocol delayed the vaccine until two months of age in cases where the mother was not sero-positive for Hepatitis B. Delaying the administration of the vaccine would put Argentine children at risk for infection, which, at such a young age would considerably increase their possibility of developing chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and/or hepatic carcinoma later in life. For this reason, the World Health Organization made the recommendation (adopted by many countries) that the first dose of the vaccine be given at birth, especially where there are insufficient resources to analyze the presence of the hepatitis B antigen in pregnant women and trace the children of infected mothers. There are other criteria to be considered when evaluating studies aimed at altering public policy, as stated in this report (Tealdi 2005:9–10):

Proof of Principle (POP) protocols, such as this, try to show to what extent a particular approach may work better than other immunization schedules… These studies do not have a direct and immediate benefit for the population under study… In these cases it is necessary to establish agreements between the sponsor and the regulatory authority and decide up to what point the proposed research may benefit the public health of the population and may be sustainable as public policy strategy… All studies in pediatric populations must be strictly regulated and controlled by the national authority, making it necessary to establish a national review system for biomedical research in general and for research on vaccines in the pediatric population in particular

As in other studies, the principal investigator was also the chairman of the ethics committee, which approved the study, and

… in spite of this, neither the informed consent nor the body of the protocol identified the existence of possible conflicts of interest… Similarly there was not any mention regarding the budget of the study and eventual disbursements such as honoraria or other payments that the researchers may receive (Tealdi 2005:10)

In addition, the evaluation by the Ministry of Justice documented the following problems: (1) the informed consent form was incomplete and had erroneous information, (2) a vulnerable population was not adequately protected, and primacy was given to scientific interest instead of human wellbeing, (3) the protocol omitted important scientific information and did not provide a careful risk – benefit evaluation for the study, and (4) there was a difference in ethical standards for the sponsor country as compared with the guest country (Tealdi 2005:12).

Later, September 20, 2005, the European Medicines Agency withdrew the vaccine that had been used in the Argentinean experiment from the European market because of its low immunogenicity against Hepatitis B (EMEA 2005). However, clinicaltrials.gov shows that nine studies using that vaccine were taking place after that date using vulnerable populations – children living in medium- and low-income countries (see Table 5.1).

5.4 Discussion

This chapter shows the political dimensions of clinical trials. The changes to provincial regulations that took place in Cordoba did not result from clinical advances or new ethical approaches to clinical research, but from the interests of elected officials and their appointed staff. The first provincial regulation was based on internationally recognized ethical principles. It has been acknowledged that compliance with these principles may delay the conclusion of the clinical trials and increase their cost, and consequently, the sponsors and the principal investigators have an interest in introducing modifications to the regulations. Some elected officials were more vulnerable to the lobbying of the investigators than others.

CEDPAP was an influential institution. The Director of the Municipal Children’s Hospital told all hospital staff that CEDPAP should be considered the research unit of the public hospital. That for the Provincial Ministry of Health, supporting vaccine clinical trials had become a provincial policy could be attributed to lobbying. One Minister of Health opened the doors of the Provincial Maternal Neonatal Hospital to the ex-Chief of Pediatrics of the Municipal Children’s Hospital – who was not allowed to continue clinical trials in the municipality due to serious allegations of regulatory and ethical violations – to conduct clinical trials.

The political dimensions of defining clinical trial regulations are also illustrated by the reaction of private foundations to the regulation that disallowed IRECs in institutions that did not offer medical care. Through lobbying, these private organizations were successful in reversing the regulation.

The lobbying power of clinical trial researchers should not be disregarded. As their relations with powerful transnational pharmaceutical corporations solidify, they acquire professional prestige. Thus, the Chief of Pediatrics of the Children’s Municipal Hospital was a member of the permanent advisory council of the Latin American Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases, and received a prize from the International Organization for Training and Medical Research (IOCIM) in recognition of his clinical research career.

This chapter also illustrates the behavior of the pharmaceutical industry. GSK did not appear to be concerned by the allegations raised by the municipality against the Chief of Pediatrics and maintained him as principal investigator of COMPAS, only to confirm several years later – through the courts – that national regulations had been violated during the implementation of the trial. We can suggest that when a pharmaceutical industry decides that a physician delivers, it will keep him/her as principal investigator for years to come. For the pharmaceutical industry, delivery means, among other things, successful lobbying and expeditious completion of trials. The fines imposed do not appear to be a deterrent to continue business as usual.

The Sanofi-Aventis clinical trial also shows the successful lobbying that private provincial institutions involved in clinical trials can have at the national level. CEDPAP continued the trial even after the European Medicine Agency had withdrawn the vaccine from its market. ANMAT and the Provincial Ministry of Health did not raise any concern, and the National Ministry of Justice seemed to be unable to stop the trial.

In Cordoba, most participants in clinical trials are poor and indigent, and are recruited primarily by their attending physician. At the end of the trial, if a medicine is commercialized, the participants will not be able to access it because of its high price. If the poor and indigent happen to be children, then we have a case of double vulnerability.

Finally, the concerns of the Municipality of Cordoba raise an additional important question. The staff of the hospitals and clinics was concerned about the interference and health risks caused by the physicians and other health workers contracted for the clinical trials. The municipal health workers considered unethical the fact that clinical trial participants were treated differently than ordinary patients, that is to say that the former received better care than the latter.

Notes

- 1.

The requested Expert Report is an activity prior to an Administrative Inquiry.

- 2.

For more information on how pharmaceutical companies value speedy recruitment see the Peruvian case study discussed in Chap. 12.

References

Ávila Vázquez, M. 2007. Globalización e identidades médicas en los ensayos clínicos. (Globalization and medical identities in clinical trials) Salud Colectiva 3(3): 235–245.

Barlett, D.L., and J.B. Steele. 2011. Deadly medicine. Vanity Fair, January. http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2011/01/deadly-medicine-201101?printable=true¤tPage=all. Accessed 27 Oct 2012.

Boletín Oficial. Provincia de Córdoba. 2007. Crean el sistema de evaluación, registro y fiscalización de los investigadores en salud (A system to evaluate, register and supervise clinical researchers is created). Boletín Oficial. Provincia de Córdoba. Resolución no. 2. Tomo 17 (Resolution number 2, volumen number 17), Jan 24.

Cámara Contencioso Administrativo de Primera Nominación. 2009. Sentencia Judicial a favor de empleada municipal que fue separada de su trabajo por colaboración con el Dr. Tregnaghi (Court Decision in favor of municipal employee who was dismissed due to having collaborated with Dr. Tregnaghi).

EMEA. 2005. Press release. European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of Hexavac. EMEA/297369/2005. http://www.medicinesauthority.gov.mt/pub/29736905en.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2012.

Fernández, M. 2005a. Córdoba: Laboratorio médico de Argentina (Cordoba: Medical Laboratory of Argentina). La Voz del Interior (Córdoba), 2 Oct. http://archivo.lavoz.com.ar/2005/1002/sociedad/nota361306_1.htm. Accessed 27 Oct 2012.

Fernández, M. 2005b. Argentina, Córdoba: Más personas controlarán ensayos clínicos (Argentina, Cordoba: More people will control clinical trials). La Voz del Interior (Córdoba), 17 Nov. http://archivo.lavoz.com.ar/2005/1117/UM/nota372128_1.htm. Accessed 27 Oct. 2007.

Fernández, M. 2006. Salud frena nuevas investigaciones médicas (Health ministry delays new medical research). La Voz del Interior (Cordoba), Dec 4. http://archivo.lavoz.com.ar/nota.asp?nota_id=24090. Accessed 27 Oct 2012.

Franco, G. 2005. Denuncia formulada por el Dr. Miguel Tregnaghi al Sr. Fiscal de Instrucción (Complaint from Dr. Miguel Tregnaghi to the Prosecutor during the Preliminary Inquiry).

Franco, G. 2006. Letter from the lawyer of Dr. Miguel Tregnaghi to Dr. Nuria Homedes.

Gobierno de Córdoba. Ministerio de Salud. 2007. Resolución 1618 Art. 17 bis (Resolution 1618, Art 17 bis), 28 Dec. http://www.cba.gov.ar/wp-content/4p96humuzp/2012/07/sal_coeis_resol1618.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2012.

La Mañana de Córdoba. 2009. Fallo judicial a favor de médicos echados por juez (Court Decision in favor of physicians dismissed by the judge), 13 May. http://www.treslineas.com.ar/fallo-judicial-favor-medicos-echados-juez-n-93373.html. Accessed 28 Oct 2012.

Mac Lean, B., and D. Degiorgis. 2005. Investigaciones científicas privadas en el hospital infantil (Private scientific research in pediatric hospital). La Fogata, Sept. http://www.lafogata.org/05arg/arg10/arg_26-13.htm. Accessed 2 Nov 2012.

Ministerio de Salud. 2006. Situación de la ética de la investigación biomédica en la Provincia de Córdoba (Assessment of the ethical situation of biomedical research in the Province of Cordoba). Ministerio de Salud. Ministerio de Salud, Provincia de Córdoba, Área de Bioética, Cordoba.

Municipalidad de Córdoba. 2005. Proyecto de Decreto. Documento no. 3675 (Draft of decree. Document number 3675), 30 Aug. http://www.cordoba.gov.ar/cordobaciudad/principal2/docs/democracia/salud/Proyecto_de_Decreto_Expte_942681_03__Htal_Infantil.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2012.

Municipalidad de Córdoba. 2006. Participación Ciudadana. Caso Hospital Infantil. Sumario Administrativo Municipality of Cordoba (Citizenry participation. Case of the Pediatric Hospital. Preliminary evaluation), 27 Sept. http://www.cordoba.gov.ar/cordobaciudad/principal2/default.asp?ir=42_4. Accessed 28 Oct 2012.

Municipalidad de Córdoba. 2007. Presentación al Informe de Peritaje del Dr. Sarasqueta (Introduction to the expert report by Dr. Sarasqueta). Córdoba. Municipalidad de Córdoba.

Municipalidad de Córdoba. Dirección de Sumarios e Investigaciones. 2005a. Reporte final no 03/05 Expediente No 942.681/03 (Final Report number 03/05 Ref: Expte. No 942.681/03), 23 Aug. http://www.cordoba.gov.ar/cordobaciudad/principal2/docs/democracia/salud/Proyecto_informe_final_Htal_Infantil_mail_elina%202.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2012.

Orchuela. J. 2006. Investigaciones clínicas con medicamentos y vacunas en hospitales públicos de Córdoba y Santiago del Estero fuertemente cuestionadas (Clinical research with drugs and vaccines in the public hospitals of Cordoba and Santiago del Estero have been strongly questioned). Boletín Fármacos 9(1): 100–105.

Puntual. 2005. El laboratorio Glaxo prueba una vacuna con 330 bebés riocuartenses (Glaxo test a vaccine on 330 babies at Rio Cuarto), 8 Nov.

Sarasqueta, P. 2004. Informe de peritaje: Caso Hospital Infantil Municipal de la ciudad de Córdoba (Evaluation report: Pediatric Municipal Hospital of Cordoba). Municipalidad de Córdoba.

Tealdi, J.C. 2005. Solicitud de opinión sobre ensayo clínico: Estudio fase II de inmunogenicidad de una vacuna combinada DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP-T comparada con PENTAXIM y ENGERIX B Pediátrico a los 2, 4, y 6 meses de edad en niños argentinos sanos. Consejo de Ética y Derechos Humanos para las Investigación Biomédicas. Secretaría de Derechos Humanos- Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos Coordinator (Request of opinion about the clinical trial: Phase II Immunogenicity of DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP~T Combined Vaccine Compared With PENTAXIM™ and ENGERIX B® at 2-3-4 Months Schedule in healthy Argentinean children. Ethics and Human Rights Council for biomedical research. Human Rights Secretariat- Ministry of Justice and Human Rights Coordinador). Buenos Aires, 8 July.

Vidal, S. 2006. Ética o mercado, una decisión urgente. Lineamientos para el diseño de normas éticas en investigación biomédica en América Latina (Ethics or market, an urgent decisión. Guidelines for designing ethical norms for biomedical research in Latin America). In Investigación en seres humanos y políticas de salud pública (Research with humans and public health policies), ed. M.G. Keyeux, V. Penchaszadeh, and A. Saada, 191–232. Bogota: Unibiblos and Redbioética UNESCO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ugalde, A., Homedes, N. (2014). Politics and Clinical Trials in the Province of Cordoba. In: Homedes, N., Ugalde, A. (eds) Clinical Trials in Latin America: Where Ethics and Business Clash. Research Ethics Forum, vol 2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01363-3_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01363-3_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-01362-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-01363-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)