Abstract

Globalization and internationalization are two concepts that are growing spectacularly in the last decades. However, multinational enterprises are facing the challenges and uncertainties of the cross-cultural context and struggling to maintain the effectiveness of their operations and the sustainability of their competitive advantage. Based on the literature research, the following report will thoroughly discuss five broad dimensions, namely: managers’ leadership skills, people management, organization’s design structure, culture and change management, which directly affect the global performance management of multinational enterprises. On one hand, it will address the theories that enable companies to overcome the challenges encountered while applying these dimensions, and accordingly maximize their tangible outcomes and their performance effectiveness. On the other hand, the report will highlight on the necessity of correlating risk management programs along with the global performance management programs and to continuously monitor their application and their alignment with the companies’ international business strategy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction to the Global Performance Management

Performance management (PM) has always been a hot topic among HR leaders (Boselie et al. 2012) searching to improve the organizations’ business processes and internal culture understanding, and to maximize employees’ performance. However, it has gained recently a critical interest worldwide, since it is affecting equally the organization itself in realizing its business strategy, and the employees in determining their career development (Evans et al. 2011).

Performance management is a strategic human resource management process described as being “an extension of performance appraisal” (Lindholm, 2000), where competencies and behaviors are reviewed and assessed according to previously determined parameters linked to corporate strategic goals, and where compensation decisions are then applied to the rating and evaluation of each individual.

While performance management acts locally in an organization, the term Global Performance Management (GPM) reveals a wider angle of this practice, spanning different cultures and countries, and covering Multinational Enterprises (MNE) spread globally throughout an international context (Knappert, 2013).

However, according to Mercer’s 2013 survey, the efficiency of the global performance management programs have not been very overwhelming recently, and only less than 3% of the companies acknowledged that these processes were truly valuable and efficient (2013 Global Performance Management Survey Report, 2013). In fact, a number of challenges are preventing their proper implementation; the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has identified five broad dimensions, namely: leadership, design, people, change management and culture, that influence global performance management programs and enable the accomplishment of the organization’s international strategy if they are continuously examined and improved.

The following report will further discuss these dimensions that challenge the achievement of a successful GPM, and how global organizations may properly address them, to consequently be able to monitor their people and operations and converge them toward clearly defined goals. The below diagram (Fig. 1) shows the research methodology adopted in this report, which will be further detailed in the following paragraphs.

(Source Haidamous, 2020)

Diagram of research methodology

2 Impact of Managers’ Leadership Skills

In today’s fast changing environments, effective leadership skills are increasingly becoming a scarce resource that cannot be translated solely through command and control. In fact, “developed markets are suffering from an exodus of older executives and developing markets straining to keep up with rapid growth” (Bhalla et al. 2011).

The primary driver that boosts the companies’ performance and enables them to successfully achieve expected results is the strength of their managers’ leadership skills and their ability to spread the organization’s culture and objectives among the entire workforce, embracing their subordinates’ humanistic needs and considerations, and aiding them to maximize their innovative outcomes through individual motivation and collective interaction. Bryan Robertson, the former director of lean transformation for Direct Line Group once said: “Our ultimate aim was to define the role of a leader as someone who coaches others to be successful and achieve their true potential” (Robertson, 2014).

The case of the Royal Bank of Canada that experienced a dramatic drop of financial returns in 2004, shows the extent to which a proper implementation of defined operational and behavioral objectives for leaders and managers can change the fate of an organization. In fact, further to the Bank’s critical situation, the senior team has set threshold expectations of behaviors and financial targets for the bank’s managers and amended the PM system to reward achieved goals. Three years later, the plan worked well and the bank’s stock price had doubled. All employees agreed that the visionary transformation was clearly reflected in the daily activities and that the leaders are still following the agreed-upon values (Bhalla et al. 2011).

Unfortunately, a detrimental phenomenon is affecting the organization and its employees in the contemporary working life which is the prevalence of destructive leadership in its passive and active forms, having serious implications on the overall PM programs, on the recruitment, and on the training and development of leaders. In fact, these concepts of leadership behaviors such as Machiavellian (Christie & Geis, 1970), authoritarian (Bass, 1990) and narcissistic leadership styles (Vries & Miller, 1984) demonstrate belittling, manipulating and humiliating behavior manners towards subordinates, and can also take the form of non-verbal aggression. They focus on control and obedience, and act as mental stressors for employees. They equally affect the legitimate organization’s interests, hinder the accomplishment of the strategic objectives and negatively impact the relationship with clients and customers (Padilla et al. 2007). They do so by neglecting or actively preventing the execution of the required tasks through sabotaging subordinates’ motivation and performance, stealing or misusing the corporate resources or aiming for individual interests regardless those of the organization (Conger, 1990).

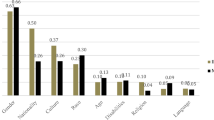

Conversely, the results of a study conducted by Müller and Turner demonstrated the effectiveness of the visionary, coaching, empathic and democratic management styles in creating a leader who succeeds in being followed and in providing adequate and enhanced work environment for his subordinates (Müller & Turner, 2007). Therefore, many companies have a big gap to fill in this regards, and Mercer’s recent studies revealed an urgent need to improve managers’ skills observed as the best lever of change: while candid dialogue was perceived as the most important driver of the overall performance management success, participants in a statistic survey claimed that almost half of managers are marginally skilled in linking individual performance to development planning, and 29% are marginally skilled in setting specific and measurable smart goals (2013 Global Performance Management Survey Report, 2013) (Fig. 2).

Elements that have the most impact on the overall success. 2013

On the other hand, managers need to be comfortable with change. To successfully face the uncertainties of foreign markets, they need to cooperate with their peers and have enough flexibility to deal with outsiders and adapt to new environments. Therefore, in order to collect the desired performance from managers, global organizations need to identify the potential leaders from the early stages of their career, and provide them with the necessary coaching to enhance their leadership skills and competencies (Bhalla et al. 2011).

3 Managing People to Achieve an Efficient Global Performance Management

A global organization’s workforce is strongly correlated with the success of its international business strategy, and can also be a source of sustainable competitive advantage if it is successfully managed at a global context and in the light of changing dynamics (Slavić et al. 2014).

Unfortunately, the vast majority of companies view their GPM program as the procedure of employees’ evaluation directly linked to compensation decisions. This pay-for-performance philosophy often lacks clear strategic assessment of the employees’ potential and competences, and rather focuses on tangible outcomes regardless of their true value. For example, only less than half of the companies focus on the personal leadership qualities of their CEO-s; instead, they address their bottom-line operational impact and achieved financial goals (2013 Global Performance Management Survey Report, 2013).

In this regard, a company is likely to adopt a GPM program that identifies and attracts talented individuals willing to challenge their capabilities. Through coaching and mentoring, they will be able to maximize their productivity and “think out of the box”, yet innovate in their field and guarantee the organization’s advantage over its competitors (Johnson et al. 2008); in this case, employees benefit from compensations beyond the simple financial incentives. To sustain their motivation, employees must sense the evolution of their career development, job rotation and autonomy. Hence, performance management should be strongly correlated with talent management programs where global organizations identify critical roles and talented individuals and focus contingency plans around them, but also, they recognize poor performers and act responsibly in their regard (Bhalla et al. 2011).

However, macro-environmental factors have seriously challenged people’s integration, and the need to adjust the GPM processes became crucial to support changing strategies that arise by entering an unknown global market, where a number of barriers are imposed, such as meeting new legal rules and regulations, new national cultures and a number of uncertainties (Slavić et al. 2014). In this context, MNEs need to avoid the risk of discrimination and inequalities against minorities through a number of guidelines that meet the diversity of today’s corporate workforce. Specifically, gender discriminating practices have become a worldwide phenomenon, and the under-representation of women in top management positions is nowadays deeply embedded in the organizational life (Meyerson & Fletcher, 2000). In France, for example, women account for only 9 percent of executive committee members (Sancier-Sultan, 2013). The literature researches showed that MNEs have put in place some initiatives aiming to avoid inequality, but have not obtained good application results for the simple reason that these measures were not very well implemented. To achieve a gender-diverse organization, an important success factor is the corporate culture that enables mind-sets to engage diversification and adaptation to dialogue, experimentation and incremental changes, to raise the levels of confidence in women leaders and to encourage the diversity of corporate management styles (Devillard et al. 2014; Sancier-Sultan, 2013).

4 The Transnational Design Structure to Insure Globalization

Global performance management researches have much debated the paradigms of convergence and divergence (DeNisi et al. 2008). The convergence paradigm seeks the adaptation of the management practices across countries driven by increased global competition and the need to find the most efficient methodologies to perform at a global context. Conversely, the divergence paradigm describes country-specific practices that remain stable over time, influenced by the organization’s legacy culture and processes (Pudelko & Harzing, 2007).

While the convergence concept is a purely economic ideology, and the divergence stresses on the national culture of the organization’s country of origin, today’s multinational enterprises need to merge these two philosophies of GPM into the idea of crossvergence; this development in performance management practices draws a more realistic picture since it allows organizations to integrate various influences, and to consider new and innovative approaches that have not been considered before (Knappert, 2013). But most importantly, this process allows for a dynamic understanding of the foreign cultures and engages continuous learning and development of the organizations’ structure and performance (Ralston et al. 2008). Accordingly, this concept of GPM must be carefully diffused to the organizations’ key elements, and translated through the company’s strategy into a source of competitive advantage.

To ensure the proper implementation of the crossvergence concept, global organizations must adopt a lean structure that minimizes the unnecessary hierarchical layers, where communication and top-down decision-making are faster, and where senior leaders can have a better view and follow-up on the daily operations (Bhalla, et al. 2011).

The latter discussion is typically applicable for the transnational structure that stresses on innovation and learning objectives, and is described by Bartlett and Ghoshal as being like a matrix with two specific features; the first is its flexibility to adapt to the challenges of internationalization through encouraging the interconnectedness of groups and functional silos and emphasizing change on both individual and strategic levels, and the second is having more fixed responsibilities within its cross-cutting dimension (Johnson et al. 2008).

5 Change Management for a Better Performance

In today’s fast-paced world, the MNEs’ ability to set new priorities and to drive change in their strategic directions quicker than their rivals became crucial (Bhalla, et al. 2011). Unfortunately, 70% of the change programs fail to achieve their goals, mainly due to a lack of two fundamentals: a proper transmission of the change initiatives from the senior executives down to the business units, and employees’ resistance (Ewenstein et al. 2015).

Therefore, change needs to be spread gradually throughout the different layers of the organization following the process of “cascading change”; this process allows the organization to ensure that the goals and means of change are well received and assimilated by the different hierarchical structures, where companies achieve a minimum sufficiency by investing the required energy to succeed through focusing on the most important elements of change, and avoiding unnecessary fragmentation of efforts (Bhalla, et al. 2011).

Regarding employees’ resistance, it is never easy to ask people to think or act differently from the way they were used to do things for many years. Bryan Robertson, in his interview with McKinsey & Company, stated that he has faced this issue in many of his transformation programs, and clarified that employees may take the time to accept change, but when they go themselves through the “change curve” they will finally realize that there are better ways of doing things and become strong advocates of the company’s new strategy (Robertson, 2014; Financial Services Practice, 2015).

Being a critical competitive advantage, change management programs are necessary for organizations’ rapid results and sustainable growth to an unprecedented degree: decision-makers have to react more quickly, managers need to adapt faster to the opportunities and threats, while front-line employees have to be more collaborative and dynamic (Johnson et al. 2008). Consequently, the introduction of digital tools will allow global organizations to adapt to the continuously changing environments much faster than the traditional workshops and training courses, and are much more efficient in the light of the scale and the diversification of their employees. Powerful digital tools will equally allow just-in-time feedbacks, create direct connections among people by sidestepping hierarchy, and minimize the physical distances between employees through achieving a level of connectivity and commitment. For example, a beverage company in Africa was experiencing share losses in its highly competitive market. The challenge was to drive more than 1000 sales representatives spread widely across countries to increase their sales. An SMS message system was implemented, and each representative received a number of daily messages that included updates on consumers and market insights along with personalized performance information. Within a year, selling increased considerably, transforming a 1.5% market share loss to a 1% gain (Ewenstein et al. 2015).

6 Organizational Culture and Performance Effectiveness

While Hofstede states that culture is the “software of the mind” shared by a group that acts similarly upon this software (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2004), organizational culture has been defined as being the shared values and attitudes inherited over time and resulting of corporate behavioral norms and practices adopted for problem-solving and for the pursuit of the inner strategy (Johnson et al. 2008).

Corporate culture has a direct impact on the organizations’ performance: a weak and ambiguous culture underperforms employees regardless the level of their capabilities whereas a strong and positive culture can increase the productivity even with average individuals. Therefore, culture and performance are interdependent and organizations cannot seek to improve their performance without considering consolidating their corporate culture (Ehtesham et al. 2011).

Denison’s theory has demonstrated this fact and has identified the four deepest cultural traits affecting the company’s effectiveness, namely: involvement, consistency, adaptability and mission, as a foundation for more common cultural components such as symbols, rituals and actions (Denison, 1989). The involvement trait requires that executives and employees feel that their work is contributing to the achievement of the organization’s strategic goals and objectives which provides them with a sense of commitment and belongingness. And since global organizations’ culture is often influenced by national factors, the necessity of determining consistency through common behaviors and mind-sets ensures the company’s stability, a high degree of conformity and an internal integration. However, effective integration can sometimes hinder change and resist new initiatives. Hence, high-performance organizations are driven by customers’ needs and expectations, and have the readiness and adaptability to take risks and change path-dependent capabilities, and amend their system and processes toward a greater value and a continuous costumers’ satisfaction. These organizations have equally well defined directions and strategic objectives that draw their mission and express a vision of the organization’s future goals and purposes (Ehtesham et al. 2011). All these cultural values that affect organizational performance have therefore a direct impact on the performance management practices and can be summarized in the below model (Fig. 3).

Examples of how organizational culture can improve MNEs’ effectiveness and their performance management are numerous. Largest insurers in North America were facing many challenges that their previous investments were not able to solve. So they have integrated a new culture into their systems through a lean management process aiming mainly to improve their workforce productivity and level of engagement, to retain and develop the existing talent, to acquire new capabilities and enhanced resources and finally to rethink and update their business models. The new culture that primarily assesses clients’ values and drives changes that continuously act upon that value was implemented, and these companies have witnessed 20 to 30 percent increased returns in the first two to three years (Financial Services Practice, 2015).

A regional healthcare system located in the southern U.S. needed a step change in performance in order to encounter the challenges ahead and yield lasting results. So it consulted McKinsey, who helped designing and implementing a lean transformation, aiming to reduce costs while improving quality, and put in a performance-driven culture that ensures sustainable results. Within less than two years, each hospital has improved its productivity and revenues and secured long-term cost-saving. The new performance management system ensured that the new standards are shared by all employees and that real-time changes are made to continuously meet the clients’ expectations (McKinsey & Company, 2016).

7 Discussion

The five dimensions previously discussed are all interrelated. They equally affect the GPM program of an organization which primary objective is to improve the company’s performance, and therefore is crucial to achieving success. A fundamental principle while conducting a GPM is to continuously link it to the MNE’s strategy and objectives, through a spiral process in which performance is continuously assessed and enhanced upon previously set parameters that are aligned with the MNE’s international business strategy (Knappert, 2013).

Furthermore, “risk management should not be a separate silo […]. To the contrary, risk management should be intimately linked to performance management” (Ernst & Young, 2009). They should be perfectly aligned and treated as being two sides of the same coin. Accordingly, risk factors should be considered in every aspect of the five GPM dimensions previously discussed, to enable the MNE to face the uncertainties and challenges of the business markets, to continuously improve its resources and capabilities, and maintain its short-term and long-term competitiveness (Fig. 4).

(Source Ernst & Young, 2009, p. 2)

Risk management aligned with performance management… two sides of the same coin

The cyclical monitoring of the GPM will increase its effectiveness, and one of the most useful tools to do so is the Balanced Scorecard developed by Kaplan & Norton (2009). It measures the application and efficiency of corporate key performance indicators (KPIs) such as customers’ satisfaction and the iron triangle (cost, time and quality), unifies culture and language, and helps in transferring the company’s vision and mission into a measurable set of individual and collective objectives (Johnson et al. 2008). These objectives are either cascaded into various KPIs from a top-down perspective, or aggregated into fewer KPIs from a bottom-up perspective, and therefore, the Balanced Scorecard becomes a link between the company’s different layers and integrates the financial and non-financial goals into the daily operations and into the performance review process.

8 Conclusion

The addressed challenges are all common issues encountered in today’s MNEs, and consist the basis of the contemporary Human Resource activities and concern. This report has discussed the five main dimensions that align organization’s needs with those of the employees, and ensure that the corporate operations and objectives converge towards an effective performance management.

As a conclusion, the major areas of GPM include the necessity of goal setting and commitment and of employees’ engagement in the organization’s life-cycle as drivers for successful work performance, constituting the line of sight between the assessment of goal attainment, the compensation decisions and finally the actions taken to improve the global performance of a Multinational Enterprise.

References

Bass BM (1990) Authoritarianism, power orientation, machiavellianism, and leadership. In: Bass BM, Stogdill RM (eds) Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: theory, research, and managerial applications. Free Press, New York, pp 124–139

Bhalla V, Caye JM, Dyer A, Dymond L, Morieux Y, Orlander P (2011) High-performance organizations: the secrets of their success. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG)

Boselie P, Farndale E, Paauwe J (2012) Performance management. In: Brewster C, Mayrhofer W (eds) Handbook of research on comparative human resource management. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, UK

Christie R, Geis FL (1970) Studies in machiavellianism. Academic Press, New York

Conger JA (1990) The dark side of leadership. Organ Dyn 19:44–55. 2 edn. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(90)90070-6

DeNisi A, Varma A, Budhwar PS (2008) Performance management around the globe: what have we learned? In: Performance management systems: a global perspective. Routledge, Abingdon [England], New York, NY, pp 254–262

Denison DR (1989) Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: a theory and some preliminary empirical evidence. School of Business Administration, University of Michigan. From Denison Consulting: https://www.denisonconsulting.com/sites/default/files/documents/resources/denison-1989-preliminary-evidence_0.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2016

Devillard S, Sancier-Sultan S, Werner C (2014) Why gender diversity at the top remains a challenge. From McKinsey & Company: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/why-gender-diversity-at-the-top-remains-a-challenge. Accessed 13 Dec 2016

Ehtesham UM, Muhammad TM, Muhammad SA (2011) Relationship between organizational culture and performance management practices: a case of university in Pakistan. J Compet (4), 78–86. http://www.cjournal.cz/files/77.pdf

Ernst & Young (2009) A new balanced scorecard: measuring performance and risk

Evans P, Pucik V, Björkman I (2011) Global performance management. Glob Chall: Int Hum Resour Manag 2:346–390. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Ewenstein B, Smith W, Sologar A (2015) Changing change management. McKinsey & Company. http://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/leadership/changing-change-management. Accessed 10 December 2016

Financial Services Practice (2015) Building a culture of continuous improvement in insurance. McKinsey & Company. www.mckinsey.com/client_service/financial_services

Haidamous (2020) Towards a high-performance global organization; dimensions, challenges and solutions of GPM programs

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ (2004) Cultures and organizations: software for the mind, 2nd edn. McGraw Hill Professional

Johnson G, Scholes K, Whittington R (2008) Exploring corporate strategy, 8th edn. Financial Times Prentice Hall, Harlow, England

Kaplan, R & Nortan, D (2009) Conceptual foundations of the balanced scorecard. Harvard Business School, pp 2–32

Knappert L (2013) Global performance management in the multinational enterprise. Berlin.

Lindholm N (2000) National culture and performance management in MNC subsidiaries. Int Stud Manag & Organ 29:45–66. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

McKinsey & Company (2016) By creating a performance-driven culture, a health system lowered costs and raised quality of care. From McKinsey & Company: Healthcare Systems & Services: http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/how-we-help-clients/creating-performance-driven-culture. Accessed 13 Dec 2016

MERCER (2013) 2013 Global Performance Management Survey Report

Meyerson DE, Fletcher JK (2000) A modest manifesto for shattering the glass ceiling. Harvard Business Review

Müller R, Turner JR (2007) Matching the project manager’s leadership style to project type. Int J Project Manage 25:21–32

Padilla A, Hogan R, Kaiser RB (2007) The toxic triangle: destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Lead Q 18:176–194. 3 edn, United States

Pudelko M, Harzing A-W (2007) Country-of-origin, localization, or dominance effect? An empirical investigation of HRM practices in foreign subsidiaries. Hum Resour Manag 46. 4 edn. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20181

Ralston DA, Holt DH, Terpstra RH, Kai-Cheng Y (2008) The impact of national culture and economic ideology on managerial work values: a study of the United States, Russia, Japan, and China. J Int Bus Stud 39. 1 edn

Robertson B (2014) Cultural change at direct line group. McKinsey & Company, Interviewer. Retrieved 10 Dec 2016

Sancier-Sultan S (2013) Women matter 2013–gender diversity in top management: moving corporate culture, moving boundaries. From McKinsey & Company: http://www.mckinsey.com/global-locations/europe-and-middleeast/france/en/latest-thinking/women-matter-2013. Accessed 13 Dec 2016

Slavić A, Berber N, Leković B (2014) Performance management in international human resource management: evidence from the CEE region. Serb J Manag 9(1). Accessed 04 Dec 2016

Vries FK, Miller D (1984) Narcissism and leadership: an object relations perspective. Fontainebleau, Human Relations, forthcoming, France

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Haidamous, N. (2024). Towards a High-Performance Global Organization; Dimensions, Challenges and Solutions of GPM Programs. In: Salman, A., Tharwat, A. (eds) Smart Designs for Business Innovation. AUEIRC 2020. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49313-3_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49313-3_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-49315-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-49313-3

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)