Abstract

The chapter, based on 61 in-depth interviews conducted in Angola in 2019 and 2022, focuses on the problem of institutional and cultural obstacles to the development of spillover effects from Chinese economic activities in Angola. The crucial institutional obstacle identified in our study is the strong presence of the state in the economies of both China and Angola. Cooperation between these countries has focused on large-scale infrastructure projects and has been based on state-to-state contracts. These contracts have often involved collaboration between Chinese SOEs and the Angolan military administration, resulting in limited social or judicial control over the cooperation standards. For example, regulations protecting the local labour force may be ignored by leveraging local connections (guanxi) and relying on military officials as local patrons. The above obstacle is reinforced by the lack of trust of Chinese businessmen towards their local business partners and their isolationist tendencies. Finally, it leads to the situation in which much less than 70 per cent of employees are local workers, which causes limitations of skills transfer possibilities. Furthermore, cultural and technological incompatibilities between Chinese and Angolan firms mean that even the limited technology and skills transfers that have occurred may become obsolete following the withdrawal of Chinese actors from Angola.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

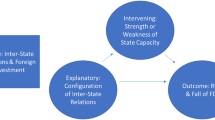

The overarching aim of the research detailed in this chapter (and throughout the book) is to examine the spillover effects of Chinese investments, as well as Chinese long-term economic activities more generally, in Africa. This broad focus stems from the observation that analysis of spillover effects is typically confined to foreign direct investment (FDI) outcomes, a framework that may be suitable for Western business practices but lacks applicability in the Chinese (and to some extent, African) context. As such, it reflects a form of conceptual eurocentrism.Footnote 1 Therefore, in the research’s latter phase, long-term project contracts initiated by Chinese companies, particularly state-owned enterprises (SOEs), were also included as potential sources of spillover effects.

Even with the expansion of the scope, the study still only identified a limited number of minor spillover effects resulting from Chinese economic activities. At the same time, multiple obstacles to the emergence of these effects were observed, attributable to a combination of economic, political and cultural factors. With the economic determinants having already been presented in earlier chapters of this book, this chapter shifts the spotlight to the institutional, political and cultural obstacles hindering the emergence of Chinese spillover effects in Angola. The findings are derived from 61 in-depth interviews conducted in Angola in 2019 and 2022 with foreign diplomats, local journalists, academics, officials, politicians and Chinese entrepreneurs, supplemented by existing literature on the topic.

The chapter proceeds as follows. Firstly, it describes the institutional features of both China and Angola relevant to the research problem, before going on to analyse how these factors contribute to the emergence of obstacles to spillover effects. Next, it examines how cultural differences can create further obstacles. Finally, the chapter assesses whether these obstacles can be eliminated given the significant changes in Chinese economic activities following the collapse of the ‘Angola model’ and the Sino–Angolan ‘marriage of convenience’ (de Carvalho et al. 2021).

Chinese and Angolan Institutional Framework

Despite China’s substantial economic involvement in Angola, both countries have distinct institutional frameworks that have resulted in a lack of significant spillover effects. With this in mind, we outline below the countries’ respective institutional and political systems.

Angola’s Institutional and Political System

Although the political system in Angola is theoretically multiparty, it is de facto dominated by the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (balance of payments) (Martins 2017). Despite receiving only 51 per cent of the vote in the most recent national elections (Vines 2022), the MPLA has been in power since Angola gained independence in 1975, with no transfers of power to another party during this time. The main opposition party, National Union for Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), whose armed forces fought the MPLA in a long and bloody civil war,Footnote 2 has little chance of winning elections (Martins 2017). In fact, as one interviewee observed, ‘In that way or another, the MPLA is going to win these elections’.Footnote 3

The MPLA, which has a long history in African politics, is actually governed by a relatively small number of influential families/clans, who compete for power while maintaining stability within the system (Martins 2017). Until 2017, power was concentrated in the hands of José Eduardo dos Santos, along with his family and close supporters (Wanda 2022).

Although officially based on Western democratic patterns, Angola’s institutional system has inherited the burden of Portuguese bureaucracy (Birmingham 1988), making it challenging to conduct business without proper contacts or facilitators among local elites. Despite President João Lourenço’s efforts to combat corruption, the bureaucratic system remains stagnant. As one interviewee asserted, the process of ‘arranging’ things has in fact become even more complicated than during the dos Santos era, when bribes were at least an option.Footnote 4

As a resource-rich country, Angola suffers from the ‘resource curse’ phenomenon (Gonçalves 2010; Teixeira 2011). Aside from the economic consequences—including price fluctuations, export vulnerability, macroeconomic instability, decline of terms of trade, Dutch Disease syndrome, fiscal mismanagement and impaired human capital accumulation (Kopiński et al. 2013)—there are significant institutional and political outcomes. The heavy reliance on natural resources and specific political systems has resulted in the state controlling a major portion of the economy (Gonçalves 2010; Rocha 2011). Here, it is relevant to note that, due to the prolonged civil war, a significant number of these state elites are associated with the military (Bernardino 2019; Roque 2022). Moreover, the fact that much of Angola’s revenue comes from resources means that the state is one of the largest employers, with little emphasis placed on developing the private sector, especially during José Eduardo dos Santos’s presidency. As a result, the majority Angola’s employed population (eight out of ten workers) work in the informal sector, while the unemployment rate is a hefty 30.8 per cent (INE 2022).

Angola’s heavy reliance on commodity exports, particularly crude oil, gas and rough diamonds, has driven the government to maintain commodity export-oriented policies. This has led to deindustrialisation and limited investment in agricultural development, which in turn has resulted in a high dependence on imports for food, beverages, clothing, footwear and medicines, as well as foreign skilled labour (Rocha 2000, 2011, CEIC 2021, IMF 2021), even though other authors have pointed to some successes in domestic-market formation via Chinese contracted project (Wolf 2017).

In 2021, Angola exported 394 million barrels of crude oil, bringing in state revenues of US$ 27.87 billion. In the first half of 2022, Angola’s GDP grew by 3.2 per cent and was estimated to grow by 2.7 per cent over the course of the entire year (Ministério das Finanças 2022, pp. 11, 17). Oil revenues accounted for an estimated 60 per cent of current revenues in the 2022 state budget (Ministério das Finanças 2021, p. 72), with the total 2022 budget amounting to just over AOA 20,104 billion (Diario de Republica 2023, p. 623), equivalent to almost US$ 40 billion. Despite the current monetary stability of the kwanza (its exchange value having gone unchanged from June 2022 to February 2023), the annual inflation rate remains relatively high at 11.54 per cent as of February 2023 (a fall from 27 per cent in March 2022) (Banco Nacional de Angola 2023).

Recently, there has been an increasing focus on local production, including food production in the agricultural sector, with an increase of about 16 per cent in non-oil revenues expected for 2023 (Ministério das Finanças 2022, p. 45). This indicates growing awareness of the need to diversify the economy and reduce dependence on oil revenues, which could lead to more sustainable economic growth in future.

Chinese Institutional and Political System

China’s system does not strictly adhere to the traditional communism envisioned by Marxist theory, which calls for the abolition of private property and a classless society. While China did once have a centrally planned economy, this has undergone significant changes since market-oriented reforms were initiated under Deng Xiaoping’s ‘opening reform’ policy of the late 1970s. Today, China’s model combines elements of socialism, market-oriented reforms and state intervention in the economy, and is often referred to as ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’. Alongside this, China’s political system is known for its lack of pluralism, limited freedom of expression and press, and strict controls on civil society. This has led to debates among scholars about the true nature of China’s system, with some arguing that it can be more accurately described as authoritarianism rather than communism (W. Tang 2016).

Given the focus of this chapter, it is unnecessary to delve into analysis of the Chinese autocratic political system itself—rather, what is important here is the role of the Chinese state in economic activities. As early as the 1980s, the Chinese government allowed the establishment of private enterprises, although initially with constraints, such as having no more than eight employees (Naughton 2007). As data published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China demonstrates, however, grassroots-based private enterprises do not comprise the majority of the Chinese economy. While there have been exceptions, such as Jack Ma’s economic empire, SOEs continue to dominate the Chinese economy, receiving preferential treatment and support from the government.

In 1994, as part of the reconstruction and commercialisation of SOEs, China’s government introduced a policy called ‘grasping the large and letting the small go’ (zhuada fangxiao) (Cao et al. 1997). The policy aimed to gradually close fundamentally unprofitable SOEs while transforming, merging and adjusting promising ones to market economy standards (Nolan and Xiaoqiang 1999). Some SOEs were fully privatised, some took on mixed forms and some remained fully state-owned (Lin and Zhu 2001).

What is noteworthy, however, is that even companies that are formally private, such as Lenovo, usually have significant connections with state institutions, such as the Chinese Academy of Science and/or state officials (Xie and White 2004). Similarly, companies like Huawei have close ties between management and the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC), including the army component. While the majority of Huawei’s ownership is officially in the hands of its employees, they are unable to sell their shares, and ownership is controlled by the labour union, which in turn is dependent on the CPC (Balding and Clarke 2019; Hawes 2021). These examples highlight the influence of the state and CPC in China’s economic activities, even in supposedly private companies.

The construction sector, which plays a crucial role in China’s economic activities in Africa, is dominated by state and public ownership (Chen et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2009). Many construction sector SOEs in China enjoy significant advantages, including access to politically related economic decisions, credit lines and state assistance in times of trouble, as evidenced by recent cases such as Evergrande (Jim and Xu 2021). These characteristics are also applicable to Chinese construction companies operating in Africa (Chen et al. 2009).

Institutional Framework and Spillover Obstacles

The above characteristics, along with Angola’s situation in the wake of the civil war, have led to a particular pattern of Chinese economic activity in Angola, known as the ‘Angola model’ (Brautigam 2011). After the war finished in 2002, Angola sought Chinese aid for the challenging task of national reconstruction. Since then, Angola is estimated to have received over US$ 42 billion of loans from China (Wanda 2023).

In 2022, 54 per cent of Angolan oil was exported to China (Permanent Secretariat of Forum for Economic and Trade Co-operation Between China and Portuguese Speaking Countries [Macao] 2023). The oil is used to pay for financing lines with China and commercial sales. Additionally, China was the largest supplier of goods to Angola in 2021, with their value amounting to US$ 1.71 billion, representing 15 per cent of total Angolan imports (Trend Economy 2022).

The most significant part of Chinese activities under the ‘Angola model’ relates to infrastructure projects funded by resource-backed loans from China Exim Bank and constructed by Chinese SOEs. Thus, to a large extent, Sino–Angolan economic relations appear dominated by state- or state-to-state-related contracts. Long-term contracts are not typically considered in analyses of spillover effects in the Western literature, as they are not classified as FDI. If, however, we consider that these long-term contracts may span several years, then—as argued in chapter four of this book—there is no reason why they should be excluded as potential sources of spillover effects.

One relevant example here is the Angolan government-supported farm development projects carried out by Chinese companies. A policy paper by the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University outlines how seven farms ranging from 1000 to 45,000 hectares were to be developed by Chinese contractors, involving construction, cultivation and worker training. For this, the Angolan government received approximately US$ 600 million of credit from Chinese banks (Zhou 2015).

Little attention has, however, been paid to the results of these projects, which according to interviewees were disappointing. Despite construction, as well as delivery of machinery and equipment, being completed, the farms were left to deteriorate, with machinery rusting away.Footnote 5

These projects had the potential not only for spillover effects but also direct developmental impacts, as they spanned several years and were supposed to include technology transfers through the training of Angolan farmers. Moreover, they were conducted in the agricultural sector, where the technology gap between China and Africa is not significant compared to, for instance, the ICT sector.

If we focus solely on the spillover effects of infrastructural projects, such as the technology transfers mentioned above, the situation does not appear any better. Theoretically, long-term projects can bring about spillover effects, such as increases in employee skills that can then be utilised in other companies, thereby strengthening the competitiveness of Angolan contractors. Reality, though, is a different picture.

The main reasons underlying why Chinese activities in Angola fail to produce significant development effects—either directly or in the form of spillovers—arise from the institutional characteristics of both countries. Firstly, state-to-state relations are often less flexible when it comes to adjusting to the local environment, building meaningful links and adapting to local conditions. Both sides have their own goals, which are not always focused on economic efficiency. Chinese SOEs typically have easy access to state support, credit lines and a Chinese labour force, strengthening a reliance on their own resources.

Secondly, Chinese SOEs are largely driven by the pursuit of profit, which may not always align with the project’s wider goals. Chinese companies often prioritise completing a project regardless of whether this means compromising on quality—as has been the case in road projects—and may even pay bribes to African officials. Corruption among African elites has regularly been cited as a reason behind the failure of Chinese projects and the resultant lack of spillover effects, such as technology transfers.

Thirdly, despite an Angolan law requiring that companies hire at least 70 per cent of their employees from the local population (X. Tang 2016), the regulation has not always resulted in significant positive spillover effects. Theoretically, the law should foster the development of local labour force skills, which can over time—through employees changing jobs—be transferred to local firms. However, this regulation has not always been respected, and even when the number of local workers has increased they have mainly been engaged in simple jobs that do not require significant skills. Additionally, Chinese construction companies often prefer to import necessary products from China and/or hire Chinese subcontractors, either directly from China or through localised Chinese companies, further limiting the potential for skills development and knowledge transfers to the local workforce. Chinese companies often attribute this to the lack of a skilled labour force in Africa, which our respondents indicated is only partly accurate. The main reason for such practices lies in the culture of Chinese companies, which will be further explored in the following section.

Another crucial aspect that enables the Chinese to bypass existing rules in Angola is inadequate implementation of regulations and a general lack of control over projects by Angolan government and state institutions, which a majority of respondents (55 per cent) mentioned when asked for their opinion on assessment of Chinese economic activities in Angola. Furthermore, 27 per cent of respondents—over half of which were, interestingly, Angolan officials—pointed out that a significant portion of Chinese projects were introduced under military agreements. Given Angola’s history and the military’s position in the country, this has made exerting control over Chinese activities extremely difficult, with the companies able to appeal directly to their military ‘protectors’—such as General ‘Kopelipa’Footnote 6—in the event of any problems.

It is worth noting that implementation of regulations may not always have the desired effect. For instance, according to an official at AIPEX (Agency for Private Investment and Promotion of Exports of Angola), a law requiring partnerships between local and foreign companies was abandoned because it was difficult for foreign companies to find Angolan partners, resulting in a lack of investment.Footnote 7 Furthermore, due to the short-term economic and political interests of both the local and Chinese sides, an environment that is supportive of local economic activities has not been properly cultivated. For example, there was lack of acceptable local suppliers when the Chinese initially established their presence in Angola, prompting the Chinese to import the materials they needed from China. During this time, the Angolan government made no effort to protect and develop local production.

Later, when regulations supporting local producers were passed, local cement and brick factories appeared on the market. This, however, coincided with the end of the construction boom in Angola, and many Chinese SOEs left the country. As a result, these local companies now not only face a lack of spillover effects, but also a general lack of demand for cement.Footnote 8

Cultural Differences as Spillover Obstacles

Cultural differences can pose significant obstacles to the emergence of spillover effects in the context of Chinese economic activities in Angola. One key factor is that China is generally a network-based society, with guanxi (relationship-building) a prominent aspect of this within the academic discourse (Jiang and Barnett 2013). Guanxi is not inherently nation-based, however, and can theoretically include members from different nations. Nevertheless, building and maintaining guanxi takes time and is typically based on mutual trust (Lee and Dawes 2005), which is not easily achieved over a short period. As a result, Chinese individuals who come to Angola often prefer to rely on their existing networks, which are typically limited to other Chinese individuals.

This reliance on established networks can limit the opportunities local Angolan companies have to benefit from spillover effects. For instance, when larger companies are looking for contractors, they may choose people they already know, which often means Chinese contractors. This mentality can also encourage more Chinese individuals to come to Angola and start businesses, as they will potentially have easier access to contracts and emerging opportunities. Thus, any horizontal spillover effects that do occur may be constrained to local Chinese companies rather than Angolan ones. The cultural difference evidenced in the Chinese network-based approach hinders the potential for spillover effects beneficial to Angola’s broader local economy.

There are also challenges related to the preparedness and absenteeism of Angolan employees working for Chinese employers. Angolan workers may need to take time off to deal with illness or death in their extended family or neighbourhood, which is not always tolerated by Chinese employers (Lelo 2015).

These issues are compounded by numerous other cultural differences, which create an atmosphere of mistrust between Chinese and Angolan workers. Differences in work ethics and understandings of concepts related to business cooperation may contribute to Chinese employers’ perception of Angolan workers as unreliable (Schmitz 2021). Moreover, there may be differences in understanding when it comes to corruption or exchanging favours. In Angola, the term ‘gasosa’ (soft drink) is used for favours, while in China ‘xiaofei’ (tip) is used. In both countries, giving or receiving favours in certain situations is considered normal. In Chinese culture, however, one is expected to provide something in return when accepting a favour, and the amount requested should not be exaggerated. According to Chinese informants cited by Chery Mei-ting Schmitz, Angolans often ask for too much in return for a favour and may not be seen as trustworthy in fulfilling their part of the exchange (Schmitz 2021).

Another factor that exacerbates these mistrust-related issues relates to a division, rooted in Chinese racism, between ‘civilised’ Chinese people (‘huaren’) and ‘barbarians’ (Dikötter 2015). According to this mindset, non- ‘civilised’ people, including Africans, are regarded as ‘barbarians’ unless they show indications of being sinicised or part of a technological and/or economically developed society.Footnote 9 This inherent belief in Chinese superiority leads to a lack of confidence in cooperating with ‘barbarians’. While Westerners have been partially excluded from this category due to the humiliation China endured in the nineteenth century, Africans are still often considered inferior and untrustworthy from an economic and technological perspective (Cheng 2011).

This lack of confidence in Africans’ professionalism is compounded by the importance of personal connections (the above-mentioned guanxi) in Chinese business culture. Angolans are unlikely to receive real skills or knowledge transfers, as Chinese employers prefer to entrust management and crucial tasks to people they trust—namely, Chinese personnel. This issue of lack of connection and Chinese isolationism was raised by several interviewees. In one case, workplace apartheid and discrimination against local workers were cited as an obstacle to skills transfers (see also Ganga 2019).Footnote 10

The language barrier can also pose a significant obstacle to cooperation and skills transfers between Chinese and Angolan workers. Most Chinese workers do not speak foreign languages, including Portuguese, which is the official language of Angola (Lelo 2015). This can make it more challenging to transfer skills and knowledge effectively. In a similar case in English-speaking Kenya, lack of proper translation was identified as a barrier to skills transfers.Footnote 11

Furthermore, lack of proper translation relating to machinery, electronic equipment and software provided by the Chinese only hinders the ability of Angolan workers to use and benefit from such technology. For example, one respondent mentioned that the machinery, electronic equipment labels and software to control their work provided for agricultural projects and the Ombaka National Stadium in Benguela were only in Chinese, preventing Angolans from using them effectively.Footnote 12

Interpersonal barriers and lack of emotional involvement between Chinese and Angolan workers can also affect the transfer of skills and knowledge. As one respondent observed, Chinese workers do not typically engage emotionally with Angolan workers,Footnote 13 with any such involvement often limited to Chinese men getting involved with Angolan women. This can create interpersonal barriers and hinder effective communication and cooperation.

There are also a number of cultural factors in Angola that can pose challenges to spillover effects. Firstly, both China (Jiang 2018) and Angola (Chêne 2010) rely heavily on patronage systems, but their understandings of how this system should work often differ significantly. This disparity can—as mentioned previously—result in increasing levels of mistrust on the Chinese side, hindering effective cooperation and skills transfers.

Secondly, local work ethics in Angola often differ from those in China, with Angolan workers sometimes prioritising the short-term impacts of their work over long-term effects or savings (Schmitz 2021). This difference in work ethic may lead to a perceived lack of reliability in the eyes of Chinese partners, again constraining the possibilities for meaningful skills transfers.

Thirdly, as a local businessman from Israel asserted, one of the biggest challenges in Angola is the pervasive atmosphere of living in hardship. Even if Angolan workers are trained, the reality of their lives outside work—including issues such as family sickness, death and poverty—may force them to prioritise personal concerns over professional development, they just obey orders instead of internalising knowledge.Footnote 14 This can lead to a swift decline in their proficiency of acquired skills.

Another interpretation of this phenomenon is that Angolan workers tend to rely on waiting for orders rather than using their own initiative and applying their learned skills in a creative way. This preference may be influenced by the priorities of the colonial education system, which, in many cases, persisted in the postcolonial period (Sifuna 2001). In essence, if children are primarily taught to memorise content provided by teachers who may not possess advanced skills (Arias et al. 2019), it becomes challenging to expect them to engage in critical thinking and effectively internalise and apply their acquired skills in a creative manner.

Lastly, the postcolonial past may contribute to a rejection attitude. Specifically, Africans may comply with orders but perceive them as imposed. Therefore the lack of internalisation can be a result of the historical legacy of colonialism.

Additionally, one interviewee revealed that Chinese employers often fail to respect Angolan labour laws, requiring workers to work long hours without proper rest and disregarding the fact that Angolan workers have children to educate at home.Footnote 15 This lack of consideration for labour laws and cultural norms further exacerbates the cultural gap, leading to resentment among Angolan workers and making it difficult for them to integrate into the Chinese work environment.

Fourthly, there is a notable cultural gap between China and Angola, as well as between China and the West. It is important to consider that Angola was one of the first African countries to be colonised, resulting in considerable internalisation of Portuguese or Lusophone culture, especially among Angolan elites. By contrast, Angolans are unfamiliar with China, potentially pushing them towards ignoring rather than internalising or integrating Chinese culture. This can result in skills obtained while working with the Chinese being perceived as irrelevant after their departure from Angola, as they may not be applicable or accepted in the local context.

A relevant example of this phenomenon can be seen in the agricultural industry, with a respondent highlighting two issues related to skills transfers involving workers who previously worked in Chinese farms.Footnote 16 The first is that the products produced in Chinese farms are typically geared towards Chinese cuisine, with the vegetables grown not familiar to or widely accepted by Angolans. As a result, when the Chinese farms left, there was no demand for these vegetables in the local market.

The second issue concerns Chinese farms’ practices, with techniques such as using human excrement as fertiliser considered culturally unacceptable, even disgusting, by Angolans. This can result in a reluctance to buy food from Chinese farms, as well as a perception that skills obtained while working in such farms, including fertilising techniques, are repugnant and useless.

Similar issues apply to other types of skills obtained by Angolans while working with Chinese counterparts, with the cultural, language and technical incompatibilities between Chinese and Angolan or Western solutions rendering the acquired skills irrelevant or ineffective in the local context. This underscores the importance of taking cultural differences and local acceptance into consideration when attempting to ensure the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of skills transfer processes.

The relevance of this is further reinforced by the recent withdrawal of Chinese companies from Angola. Any technology or skills transfers that have occurred may become useless in the wake of these companies’ departure due to uniqueness of Chinese solutions and technology. Thus such withdrawal can result in limited developmental effects of Chinese presence (infrastructure excluded), as local people may be unable to effectively utilise previously acquired skills when they come to cooperate with local, Western or Brazilian companies.

Summary and Conclusion

One of the main reasons behind the limited developmental impacts of Chinese economic activities in Angola, including indirect spillover effects, is the technological gap as discussed in Chapter 3 and underdevelopment of the local business sector and industry. On top of this, institutional and cultural factors further diminish the potential for positive outcomes.Footnote 17

Among the institutional factors, the strong presence of the state in the economies of both countries is particularly significant. Cooperation between China and Angola has largely focused on large-scale infrastructure projects necessary for post-war reconstruction, and been based on state-to-state contracts. These contracts have often involved collaboration between Chinese SOEs and the Angolan military administration, resulting in limited social or judicial control over cooperation standards. This lack of oversight has impacted the quality of construction and may have reduced the effectiveness of regulations such as the requirement that 70 per cent of employees be local workers, which could have facilitated skills transfers. More generally, inflexibility and lack of adjustment to local needs in state-to-state cooperation can render an entire project ineffective in terms of direct and indirect developmental effects.Footnote 18

The cultural features of Chinese and Angolan society also contribute to institutional spillover obstacles. Both cultures place strong emphasis on informal network-based business relations, which can have significant repercussions, including the potential for corruption. According to informants, Angolan elites often initiate projects with the primary goal of obtaining commissions, which can amount to 10–20 per cent of the contract value.al.

When the focus is solely on personal gain rather than the actual outcomes of a project, the probability of achieving spillover effects is very low. This is because there is a lack of control over Chinese activities from the Angolan side. Additionally, from the perspective of the Chinese, such effects may not be seen as profitable for them.

On the Chinese side, while they generally accept the idea of ‘exchange of favours’, they may not be amenable to the lack of reciprocity in business relations, leading to a lack of trust towards local business partners. This can hinder cooperation development, including skills and knowledge transfers. Moreover, Chinese isolationist tendencies can reinforce mistrust, resulting in a preference for hiring their own people instead of local workers or contractors. Local regulations protecting the local labour force may be ignored by leveraging local connections (guanxi) and relying on military officials as local patrons. Furthermore, cultural and technological incompatibilities between Chinese and Angolan solutions mean that even the limited technology and skills transfers applicable to Chinese working environment that have occurred may become obsolete following the withdrawal of the Chinese presence from Angola.

The various issues detailed above mean the effects of Chinese economic activities in Angola appear primarily to have been restricted to mobile technology and infrastructure development (often of low quality), as well as trade (with an unfavourable trade structure for Angola). Meanwhile, Angola is left with significant debt and a lack of substantial developmental impacts, including spillover effects.

If significant spillover effects arising from Chinese economic activities in Angola are to occur going forward, then the institutional, cultural and economic obstacles that have limited developmental impacts thus far need to be addressed. This, however, may not be a straightforward task, for a number of reasons.

Firstly, addressing the institutional challenges would require reducing corruption, improving regulatory frameworks and ensuring social and judicial control over cooperation standards. This would necessitate significant reforms in both China and Angola aimed at creating a more transparent and accountable business environment.

Secondly, addressing the cultural challenges would require building trust and reciprocity in business relations, overcoming isolationist tendencies and promoting local participation and compliance with regulations. This would necessitate efforts from both Chinese and Angolan parties to understand and respect each other’s cultural norms and practices.

Thirdly, addressing the economic challenges would require diversifying economic cooperation beyond infrastructure and trade, and promoting skills and knowledge transfers to build local capacity. This would necessitate strategic planning, investment in education and training, and promoting entrepreneurship and innovation in Angola.

Substantial Chinese withdrawal from Angola and growing scepticism in some African countries towards continuing economic cooperation with China pose additional challenges. Overcoming these may require a complex reformulation of the cooperation model, including a shift towards more ‘people-to-people’ focused relations rather than just state-to-state contracts. Such a reformulation would involve local communities, businesses and civil society assuming a greater role in decision-making processes and project implementation.

Overall, achieving significant spillover effects from future Chinese economic activities in Angola requires a comprehensive approach involving institutional, cultural and economic reform, as well as a willingness from both countries to adapt their cooperation model. Issues related to debt sustainability, environmental sustainability and social inclusiveness also need to be addressed if a more sustainable and mutually beneficial partnership between the countries is to be constructed.

Notes

- 1.

See Chapter 5 of this book.

- 2.

- 3.

Interview with Angolan official, 12.05.2022, Luanda, Angola.

- 4.

Interview with Angolan official, 12.05.2022, Luanda, Angola.

- 5.

Interview with journalists, Benguela, 20.05.2019.

- 6.

General Manuel Hélder Vieira Dias Jr., Angolan general, public official and businessman closely associated with former president José Eduardo dos Santos.

- 7.

Interview with AIPEX officer, 25.05.2019, Luanda, Angola.

- 8.

Interview with foreign businessman, 10.05.2022, Luanda Angola.

- 9.

Of course, we do not claim that this applies to all the Chinese present in Angola; at the same time, however, we cannot pretend the issue does not exist. Moreover, such attitudes do not, sadly, pertain only to the Chinese.

- 10.

Interview with Angolan journalist, 20.05.2019, Benguela, Angola.

- 11.

Interview with Kenyan academic, 5.02.2022, Kilifi, Kenya.

- 12.

Interview with Angolan journalist, 20.05.2019, Benguela, Angola.

- 13.

Interview with Angolan journalist, 21.05.2019, Benguela, Angola

- 14.

Interview with foreign entrepreneur, 12.05.2022, Luanda, Angola.

- 15.

Interview with Angolan official, 25.05.2019, Luanda, Angola.

- 16.

Interview with Angolan academic, 19.05.2022, Luanda, Angola.

- 17.

Chinese are becoming increasingly aware of the cooperation problems, which is reflected in their efforts to introduce Chinese Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) into the African context, as described by Tan Mullins (2020). However, it should be noted that many of these initiatives are largely declarative in nature and may not always translate into concrete actions. This can be seen in the case of the described in the text Angolan farm projects. Furthermore, even if these activities were to be implemented, they may no longer be applicable to Angola due to the significant withdrawal of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) from the country.

- 18.

A good example of such a project could be the big, empty hotel on the outskirts of the small Angolan town of Sumbe.

References

Anstee, M. (1996) Orphan of the Cold War. The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Angolan Peace Process, London: Macmillan.

Arias, O., Evans, D.K. and Santos, I. (2019) The Skills Balancing Act in Sub-Saharan Africa Investing in Skills for Productivity, Inclusivity, and Adaptability.

Balding, C. and Clarke, D.C. (2019) ‘Who owns Huawei?’, SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.3372669.

Banco Nacional de Angola (2023) Evolução Mensal da Taxa de Inflação Nacional, viewed 20 March 2023: https://www.bna.ao/#/pt/estatisticas/consultar-dados/estatisticas-preco-contas-nacionais/evolucao-mensal-tx-inflacao/nacional.

Bernardino, L.B. (2019) As Forças Armadas Angolanas. Contributos para a edificação do Estado, Lisboa: Mercado de Letras.

Brautigam, D. (2011) The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. OUP Oxford. Available at: https://books.google.pl/books?id=X2g2rEMSdIYC.

Birmingham, D. (1988) ‘Angola Revisited’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 15(1), pp. 1–14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03057078808708188.

Cao, Y., Qian, Y. and Weingast, B.R. (1997) ‘From federalism, Chinese style, to privatization, Chinese style’, SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.57564.

Chêne, M. (2010) Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in Angola. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute (U4 Helpdesk Answer). Available at: https://www.u4.no/publications/overview-ofcorruption-and-anti-corruption-in-angola.

de Carvalho, P. (2002) Angola. Quanto Tempo Falta para Amanhã? Reflexões sobre as crises política, económica e social, Oeiras: Celta Editora.

de Carvalho, P., Kopiński, D. and Taylor, I. (2021) ‘A marriage of convenience on the rocks? Revisiting the Sino–Angolan relationship’, Africa Spectrum, 57(1), pp. 5–29. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/00020397211042384.

CEIC (2021) Relatório económico de Angola. 2019/2020, Luanda: CEIC da Universidade Católica de Angola. Available at: http://www.embajadadeangola.com/pdf/RELATORIO-ECONOMICO-2019-2020-VERSAO-FINALISSIMA-18-AGOSTO-2021Relatorio2021_01a264_FINAL.pdf.

Chen, C., Goldstein, A. and Orr, R.J. (2009) ‘Local operations of Chinese construction firms in Africa: An empirical survey’, International Journal of Construction Management, 9(2), pp. 75–89. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2009.10773131.

Cheng, Y. (2011) ‘From campus racism to cyber racism: Discourse of race and Chinese nationalism’, The China Quarterly, 207, pp. 561–579. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741011000658.

Correia, P.P. (1996) Angola. Do Alvor a Lusaka, Lisboa: Hugin.

Diario de Republica (2023) Article 2, number 2, of the Law nr 2/23, 13th March, I Série, nr 47, page 613.

Dikötter, F. (2015) The discourse of race in Modern China. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://books.google.pl/books?id=ZpGMCwAAQBAJ.

Ganga, A. (2019) A gropolítica do petróleo angolano e a sua inserção na relação sino-angolana, Lisboa: Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa. Available at: https://repositorio.ual.pt/bitstream/11144/4464/1/A%20diss%20alice%20G..pdf.

Gonçalves, J. (1991) Angola a fogo intenso. Ensaio, Lisboa: Cotovia.

Gonçalves, J. (2010) ‘The economy of Angola: From independence to the 2008 worldwide crisis’, The Perspective of the World Review, 2(3), pp. 73–89. Available at: https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/6357/1/PWR_v2_n3_Economy.pdf.

Guimarães, F.A. (1998) The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict, London: Macmillan.

Hare, P. (1998) Angola’s Last Best Chance for Peace. An Insider’s Account of the Peace Process, Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Hawes, C. (2021) ‘Why is Huawei’s ownership so strange? A case study of the Chinese corporate and socio-political ecosystem’, Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 21(1), pp. 1–38. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14735970.2020.1809161.

IMF (2021) Quinta avaliação do Acordo Alargado do abrigo do Programa de Financiamento Ampliado e pedido de modificação dos critérios de desempenho, Washington, DC: Fundo Monetário Internacional. Available at: https://www.ucm.minfin.gov.ao/cs/groups/public/documents/document/aw4x/ntkz/~edisp/minfin1593723.pdf.

INE (2022) Indicadores de Emprego e Desemprego. Inquérito ao emprego em Angola, Luanda: Instituto Nacional de Estatística.

Jiang, J. (2018) ‘Making bureaucracy work: Patronage networks, performance incentives, and economic development in China', American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), pp. 982–999. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12394.

Jiang, K. and Barnett, G.A. (2013) ‘Guanxi networks in China’, Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia, 12(2), pp. 89–97. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17477/jcea.2013.12.2.089.

Jim, C. and Xu, J. (2021) China Asking State-Backed Firms to Pick Up Evergrande Assets—Sources | Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-asking-state-backed-firms-pick-up-evergrande-assets-sources-2021-09-28/ (Accessed: 14 February 2023).

Jorge, M. (2000) “O conflito em Angola: natureza e perspectivas”, in: La Réconciliation en Angola. Une Contribution pour la Paix en Afrique Australe, Paris: Centre Culturel Angolais, pp. 111–124.

Kissinger, H. (1999) Years of Renewal. The Concluding Volume of His Memoirs, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kopinski, D., Polus, A. and Tycholiz, W. (2013) ‘Resource curse or resource disease? Oil in Ghana’, African Affairs, 112(449), pp. 583–601. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adt056.

Lee, D.Y. and Dawes, P.L. (2005) ‘“Guanxi”, Trust, and long-term orientation in Chinese business markets’, Journal of International Marketing, 13(2), pp. 28–56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.13.2.28.64860.

Lelo, C.K. (2015) A influência do absentismo no ambiente de trabalho. Estudo de caso numa instituição de ensino da saúde angolana, Lisboa: Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/48584584.pdf

Lin, Y. and Zhu, T. (2001) ‘Ownership restructuring in Chinese state industry: An analysis of evidence on initial organizational changes’, The China Quarterly, 2001/08/24, 166, pp. 305–341. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S000944390100016X.

Martins, V. (2017) ‘Politics of power and hierarchies of citizenship in Angola’, Citizenship Studies, 21(1), pp. 100–115. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2016.1252718.

Messiant, C. (1994) ‘Angola: Le retour à la guerre ou l’inavoulable faillite d’une intervention internationale’, L’Afrique Politique, pp. 199–229.

Ministério das Finanças (2021) Relatório de fundamentação do orçamento geral do Estado 2022, Luanda: Ministério das Finanças (draft).

Ministério das Finanças (2022) Relatório de fundamentação do orçamento geral do Estado 2023, Luanda: Ministério das Finanças (draft).

Naughton, B. (2007) The Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth. The MIT Press.

Nolan, P. and Xiaoqiang, W. (1999) ‘Beyond privatization: Institutional innovation and growth in China’s large state-owned enterprises’, World Development, 27(1), pp. 169–200. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00132-6.

Permanent Secretariat of Forum for Economic and Trade Co-operation Between China and Portuguese Speaking Countries (Macao) (2023) China Was One of the Main Destinations for Angolan Crude Oil in 2022, viewed 5 May 2023: https://www.forumchinaplp.org.mo/china-was-one-of-the-main-destinations-for-angolan-crude-oil-in-2022/.

Rocha, M.A. (2000) Por onde vai a Economia Angolana?, Luanda: Executive Center and Luanda Antena Comercial.

Rocha, M.A. (2011) Alguns temas estruturantes da Economia Angolana. As crónicas do jornal Expansão 2009–2011, Luanda: Kilombelombe.

Roque, P.C. (2022) ‘The Angolan armed forces: A strained national pillar’, in Governing in the Shadows: Angola’s Securitized State. Oxford University Press, pp. 129–168. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197629895.003.0005.

Schmitz, C.M. (2021) ‘Making friends, building roads: Chinese entrepreneurship and the search for reliability in Angola’, American Anthropologist, 123(2), pp. 343–354. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13558.

Sifuna, D. (2001) ‘African education in the twenty-first century : Challenge for change’, Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 4(1), pp. 21–38.

Tan Mullins, M. (2020) ‘Smoothing the Silk Road through successful Chinese corporate social responsibility practices: Evidence from East Africa’, Journal of Contemporary China, 29(122), pp. 207–220. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1637568

Tang, W. (2016) Populist authoritarianism: Chinese political culture and regime sustainability. Oxford University Press.

Tang, X. (2016) ‘Does Chinese employment benefit Africans? Investigating Chinese enterprises and their operations in Africa’, African Studies Quarterly, 16(3–4), p. 107.

Teixeira, C. (2011) ‘A nova constituição económica de Angola e as oportunidades de negócios e investimentos’, Lisboa. Available at: https://www.fd.ulisboa.pt/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Teixeira-Carlos-Nova-Constituicao-Economica-de-Angola.pdf.

Trend Economy (2022) Annual International Trade Statistics by Country, viewed 5 May 2023: https://trendeconomy.com/data/h2/Angola/TOTAL.

Vines, A. (2022) Angola’s Political Earthquake: The Aftermath of the August 2022 Elections. Available at: https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/angolas-political-earthquake-aftermath-august-2022-elections-36067 (Accessed: 8 November 2022).

Wanda, F. (2022) ‘The political economy of partidarização within the postcolonial state in Angola’, Journal of the British Academy, 10(s6), pp. 99–122.

Wanda, F. (2023) ‘Milagre ou mirage? Para onde foi o dinheiro da China?’, Expansão, 22 Jan. Available at: https://www.expansao.co.ao/opiniao/fernandes-wanda/interior/para-onde-foi-o-dinheiro-da-china-111654.html

Wolf, C. (2017) ‘Industrialization in times of China: Domestic-market formation in Angola', African Affairs, 116(464), pp. 435–461. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adx015.

Wright, G. (1997) The Destruction of a Nation. United States’ Policy Toward Angola Since 1945, London: Pluto Press.

Xie, W. and White, S. (2004) ‘Sequential learning in a Chinese spin-off: The case of Lenovo Group Limited’, R&D Management, 34(4), pp. 407–422. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2004.00349.x.

Zhou, J. (2015) Neither ‘Friendship Farm’ nor ‘Land Grab’: Chinese Agricultural Engagement in Angola.

Zhou, J.L., Fang, D.P. and Chen, C. (2009) ‘Chinese state-owned construction enterprises in the international market: A gap analysis’, in International Conference on Global Innovation in Construction, United Kingdom: Loughborough University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jura, J., de Carvalho, P. (2023). Institutional and Cultural Obstacles of Chinese Spillover Effects in Angola. In: Kopiński, D., Carmody, P., Taylor, I. (eds) The Political Economy of Chinese FDI and Spillover Effects in Africa . International Political Economy Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38715-9_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38715-9_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-38714-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-38715-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)