Abstract

This paper focuses on the effects of longevity on the changes in returns to education, as well as human capital and economic growth. Health issues and the quality of life may reduce human capital which can be defined loosely and thus decrease income over the lifetime. The income effects of health are likely to vary depending on how health changes (for example morbidity vs. mortality) and at what time of life (for instance, infancy, working age or older). In this paper, we show that higher rates of longevity improvements would also boost economic growth, even if we eliminate the human capital formation mechanism and only look at the growth effects from higher rates of longevity improvements due to investments in physical capital. We show that some researchers find large labor market returns on height in adulthood, which is to a certain extent a proxy for early-life health. In addition, we deduct the trend that while lower mortality moves populations to a new path of growth, where that path ultimately lands depend on how fertility adjusts to changes in health. By these extrapolations, improved health would inevitably lead to larger gains for unhealthy regions, even though the gaps between rich and poor countries are orders of magnitude larger than gains estimated in the micro-literature. Furthermore, we discuss in detail the aggregate implications of the micro-estimates and point out the complications when extrapolating to the aggregate equilibrium, particularly due to the effects of health status on the population size.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Classification

1 Introduction

The issue of longevity, the health status and the quality of life have troubled the economists for decades. Most importantly, the link between longevity and the changes in returns to education, human capital, and economic growth are in the focus of economic theory (Ahmad & Khan, 2019; He & Li, 2020). In general, in all countries—low, middle, or high-income—there are always large and quite substantial differences in health outcomes across all social groups. On one hand, low-income and middle-income countries also have to solve the issues of nutrition as a part of healthy diet and thence a healthy way of living (Bennett et al., 2018). On the other hand, some middle-income and most of the high-income countries have to face the issue of obesity which represents a serious health risk, shortens the life span, and becomes a serious financial burden for the healthcare system and thence for the whole economy, as taxpayers have to cover the costs of healthcare for obese people suffering from such common civilization diseases as diabetes, high blood pressure, various form of cancer, or cardiovascular diseases (Ameye & Swinnen, 2019).

Some studies examine long-term associations between nutrition during the intrauterine period or in early infancy and non-health-related outcomes later in life in low-income and middle-income countries (Washio et al., 2021). Economists study the effect of early-life nutrition on adult health, education, marriage, and economic outcomes. Despite the potential for significant health, education, and economic benefits, the efficacy nationally has been often challenged (Lu et al., 2020). Other components can also reinforce potential nutritional effects, improving children’s general health and nutrition. The use of other community-based health programs may have increased after nutrition was introduced to intervention villages, leading to a possible confounding effect on adult outcomes. The lower rates of marriage across the settlements might have been associated with significant effects on women’s health and demography, as well as children’s health. This is in line with studies showing different effects of men’s and women’s labor market conditions on other children’s outcomes (Moskvina, 2022; Reichelt et al., 2021). Overall, the results stemming from many related studies suggest that increased child weights with an improvement in female labor markets may result from decreased household time to prepare meals. In particular, an increase in the amount of time spent paying for childcare and medical care suggests that improvements in the male labor market had beneficial effects on the children’s weight (a reduction in body mass) by increasing the health investments in children (Bertrand et al., 2021). In terms of predicted growth rates of men’s employment, economists find substantial effects of time spent buying prepared foods and time spent paying for child care and medical care. When looking at effects of female labor markets, we find a one-percentage-point increase in predicted female employment growth rates is significantly and positively associated with BMI, the probability of being overweight or obese, and the probability of being obese. Besides the fixed effects at individual, county, and time, the models for the linear county-specific trend over time are built in order to capture existing parallel trends of women’s labor market participation and increased overweight and obesity. In both extended and within-sibling models, there appears to be no effects of the poor child health of one spouse on labor supply for the other (Fang & Zhu, 2022).

The standard expectation is that, because of the usual non-observed household effects that are related both to child health and to adult outcomes, estimates of within-family effects of child health will be smaller. The standard expectation is that due to common unobserved family effects, correlated both with childhood health and adult outcomes, that within family estimates of impacts of childhood health would be smaller. Although this is frequently claimed as an advantage for using schools as a proxy, these findings suggest this argument is likely to be exaggerated, because health at an earlier age (which is related to later health) can modify educational attainment at a later age (Levasseur, 2020). One challenge with attributing effects to childhood health is the high likelihood that other, yet-to-be-measured, dimensions of the family environment may still exist, and these dimensions could relate both to education at an earlier age to health at an earlier age (Mishra & Singhania, 2014).

To fully understand how education influences economic growth, we must be able to understand more comprehensively its effects on a country’s economy. However, economic models have left out indirect relationships between the cognitive effects from education (Litau, 2018) to labor supply via health. Economists suggest that an education-enhanced-health model of human capital provides a stronger political case for education, by capturing both educations direct effects on labor supply as well as indirect effects on labor supply via its effects on health. Education appears to affect the supply overlabor directly as well as indirectly via improvements in adult health (Setzler & Tintelnot, 2021).

In order to fully measure the indirect effects of education via adult health on labor force supply, education level and health status in adulthood are often included. Since labor force supply and adult health are the main variables, inclusion of both father’s and mother’s education is essential to the model construction. Father’s education has a large effect on labor force supply, while, in the same time, mother’s education has significant effects on health during childhood and early adulthood (Mörk et al., 2020).

Some researchers in the fields of economics or sociology explore the effects of child health on the observed economic and social outcomes in adulthood—education levels and trajectories, household income, family wealth, personal earnings, as well as labor supply. They present evidence that even nutrient intake during infancy influences health outcomes well after the individuals own adulthood (Cheng & Song, 2019). Although these studies generally control for an array of observed socioeconomic and demographic factors, the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models typically used for them cannot resolve the possibility for reverse causation, or a third factor driving both obesity and labor market outcomes. When significant on-observable factors are temporally variable, or if reverse causality is suspected, studies may employ instrumental variables to examine both obesity and labor market outcomes. Finding that is strongly predictive of an individual’s obesity, but is not related to labor market outcomes other than by its impact on obesity, is quite challenging. Although its validity would be compromised if the multitude of genes that are associated with obesity were also associated with other factors affecting labor market outcomes, such as the desire to postpone gratification (time-discounting), most studies failed to find any effects of common family environments on bodyweight. This approach will produce distorted estimates of the effects of obesity on earnings insofar as those factors are not captured by observable factors, such as education, or parents respond differentially to children's early signs of academic potential in ways related to future earnings.

2 Health Status and Income

There is some evidence stemming from the economic theory that income is correlated with the health status. People with various degrees of income tend to have varying degrees of health issues and problems (Strielkowski et al., 2022). This is explained by differences in the overall educational attainment, the distribution of resources and wealth, as well as in the strengths of health systems (Chvátalová, 2016). Given this, the utility of these measures when reviewing and assessing gender equality across higher-income countries is limited, and can obscure significant gender inequalities within these countries. This is also related to the differences in job satisfaction and thence mental health and happiness (Čábelková et al., 2016). Our literature review conducted in this section of our paper using a vast body of the economic literature identified only a few studies applying multidimensional measures of gender equality in relation to health outcomes in high-income countries. Given the motivations highlighted in the above points, the aim of the present paper is to first, systematically review multidimensional measures of gender equality across countries that have been used as the outcome of exposures in studies on health outcomes in high-income countries, and second, assess to what extent they are related to health outcomes.

In general terms, the assessment and monitoring of gender inequalities in high-income countries remains a priority. Here, we can compare inequalities between income levels in health and perceptions of health in high-income countries and in middle-income countries around the world. Many related studies focus on differences between individuals in their countries highest share of household income versus their countries lowest share, comparing respondents’ experiences and views in the two-thirds with respect to their own health and healthcare (Kansiime et al., 2021).

To examine how the extent of the tolerance of income-based disparities in health care might differ across nations and regions, it is possible to compare the proportion of people in each country morally concerned about unequal access to health care among income groups given that country’s level of perceived unmet health care needs. In all other high-income countries with similar low to moderate levels of concern about income-based health care inequality compared with the U.S. (such as Australia, Finland, Great Britain, and Taiwan) most respondents typically feel that their basic health needs are being met (Hero et al., 2017).

Variation among countries in the disparities in health care and medical assistance did not seem to be driven by differences in the level of wealth across various states. Moreover, it appeared that the ways people self-reported their health status differed considerably in the countries with high income and middle income. A review of papers examining income inequality and health among populations yield some interesting results that health was generally worse in societies with lower levels of inequality, particularly when the inequality was measured on larger geographical scales. In addition to that, it appears that the determinants of population health can differ from those for individual health (Abulibdeh, 2020; Alfani, 2022).

Although we know that individuals who are unemployed and low-income experience higher mortality, that does not necessarily imply that populations experiencing higher levels of unemployment or lower average income experience higher mortality. Therefore, it is important to understand population health on the social dimension, taking into account the total context that populations are living in. Even though the existence of health inequalities is an almost universal issue, it has been shown that the degree to which societal factors are relevant for health differs across countries. Health disparities negatively impact groups of individuals who systematically have experienced greater barriers to health on the basis of their race or ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, gender, age, mental health, as we as many other characteristics (Vela et al., 2022).

Researchers suggest that in United States racism which has produced segregated neighborhoods with few hospitals, higher rates of chronic illnesses, and uneven access to care is a major culprit. For the majority of African-Americans, American government’s promises for improving access to healthcare still cannot be fully materialized (Manuel & Herron, 2020). In addition, African Americans are more likely to suffer adverse income shocks, and are less likely to have the ability to rely on savings or access to financial help from friends or relatives when emergencies arise, like when an illness strikes. For instance, 30 percent of older African American married couples and 50 percent of older black singles were dependent on social security schemes for the lion’s shares of their incomes. The initiatives by the American law-makers aimed at raising the retirement age above 67 years of age will disproportionately hurt African American citizens and all Americans regardless with lower well-being or worsening health outcomes, serving as benefit cuts (Park et al., 2019).

This is a reflection of the 10/90 divide, wherein less than 10 percent of the funding allocated for healthcare research in developed countries is directed at problems that impact 90 percent of the global population, with even smaller proportions going to funding researchers and healthcare issues that are native to developing countries. Given the quality of evidence found, we can state that countries with social democratic institutional arrangements, higher government expenditure, lower income inequality, and policies to provide safer workplaces and access to education and housing tend to have better-health populations.

3 Improving Longevity and Reducing Mortality

Across the world, economist observe some differences in the mortality structures of populations. A drop in the death rate, unless it is accompanied by, or preceded by, a corresponding drop in fertility, will precipitate rise in the population, possibly leading to lower output per capita (Cazalis et al., 2018). Higher longevity can result in a larger population, which can reduce income per capita if there are Malthusian (congestion) effects. The tool takes advantage of what is called the epidemiological transition following the Second World War, which led to an exogenous decrease in deaths due to several major infectious diseases. The results obtained in a number of studies document that higher life expectancy has little impact on growth of total income, but has large effects on the increase of population, thus leading to substantial decreases in income per capita (Sharma, 2018).

Moreover, other results suggest that introducing a government-run healthcare system leads to substantial reductions in infant mortality and crude death rates, which, in turn, has significant positive effects on growth. Mackenbach et al., (2015), for example, linked rising national well-being with decreased deaths from infectious diseases across European countries from 1990–2008, when they examined the upward shift in the Preston Curve (the relationship between real income and life expectancy) across set of European countries. The association of health and GDP for Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries during the past two centuries shows that GDP per capita and gross domestic product had significant impacts on life expectancy in most countries (Stefko et al., 2020), which was then followed by lower death rates. Early studies typically found strong positive associations between health and economic outcomes, defined as the level of either GDP growth per capita or per capita. Superior longevity and health were associated with increased productivity, which is the essential stimulus to sustained economic expansion. While among working-age populations primarily captures the impact of health on economic growth, which is mediated by labor supply and productivity, mortality across populations also accounts for macroeconomic effects from the survival rates in older populations, via savings, investment decisions, and welfare spending, among others (Kudins, 2022; Strielkowski & Weyskrabova, 2014). In terms of income inequality, Yapp and Pickett (2019) found that those states that yielded larger disparities in income also tended to exhibit worse results in terms of such health indicators as years of age, obesity, premature death, increased rates of homicide, and higher rates of mental illness.

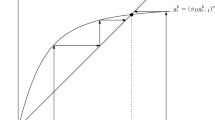

4 General Equilibrium Model of Health Capital

The impact of health-related issues on the economic growth and well-being is often calculated using the General Equilibrium Models. Using these economic models allows the researchers to grasp the relevance of a feedback effect on the health-related benefits from an environmental policy (Kang et al., 2019; Kumar et al., 2019). The results stemming from these calculations that is reported in numerous studies suggest that explicitly modeling the health-related effects of air pollution on consumers and producers allows for more accurate estimates of the effects of an environmental policy on private consumption and employment (Brodeur et al., 2021; Shan et al., 2021). One of the types of models that is used widely by the economists for estimating the full-scale effects of changes in trade policies, for example, as the outcome of the round of multilateral trade negotiations, is the applied general equilibrium model (often called the “computed general equilibrium” (CGE) model). Computable General Equilibrium models constitute an important part of the development of economic science in the last two centuries or so (Nugroho et al., 2021; Soummane & Ghersi, 2022).

Another common type isa partial equilibrium model, which estimates the effect of a trade policy measure on specific sectors rather than on the overall economy (Chodorow-Reich, 2020; Ferraro & Cristiano, 2021). Partial equilibrium models do not capture the connection to other sectors, and are therefore useful where spillover effects are expected to be small. The dynamic general equilibrium models for the four European Union economies presented in some studies are based on the intertemporal optimization decisions of households and firms. In the present framework, the models break down household sectors in these four economies according to their income deciles. In this type of models, food for direct human consumption is projected in per capita terms using base-year data on income per capita. For instance, the growth in food consumption following growth in per capita income only, independent of changes in the distribution of income, is almost 50% during a 40-year period (Baarsch et al., 2020). Given the estimated spending elasticity of global food consumption as well as the increase in food consumption obtained by the more optimistic forecast of a five-per-cent decline in the Gini coefficient over 40 years could have been achieved by just slightly more than 2 years of growth of per capita income to its present level. Under the assumptions made, a rise of 8 per cent in the Gini coefficient over 40 years would produce a decrease of around 5 per cent in food demand per capita, whereas a 5 per cent drop in the Gini coefficient would produce an increase of around 2–3 per cent in per capita food consumption in 40 years, relative to an income distribution-neutral growth scenario (Lakner et al., 2022). Paradoxically, over the short-term to medium-term, a poor-friendly growth scenario, which decreases inequality through faster increases in per capita incomes in developing countries, results in higher growth of demand, as incomes increase most for those households that have higher elasticity of demand. Other factors may change demand; for instance, rising incomes shift the demand curve of an ordinary good outward from its origin.

Demand functions are programs that indicate what households will want to purchase at given prices using their income. Demand theories describe the rational choice by individual consumers to purchase a most preferable amount of each good given their income, prices, tastes, and so on. Public-sector fiscal and transfer policies influence households’ incomes by their effects on those relative prices (Shulman & Geng, 2019). Governments that deliver public goods and transfer revenue to households raise revenues through direct and indirect taxes, although the former is more significant than the latter for the four European Union economies. Households accept commodity prices as given, and they discount future earnings using the reference rate in order to arrive at a present value of lifetime earnings. Neoclassical economics perceives its main tools, supply and demand, as the main price and quantity settlers in the market that is set in its equilibrium state, which influences both output distribution and income distribution. Modern mainstream economics builds upon neoclassical economics, but with a number of refinements either complementing or advancing in the novel realms of economic science such as the econometrics, game theory, as well as economic growth models (e.g., Solow model) to analyze the long-run variables that influence national income.

Macroeconomic analysis also looks at factors that influence long-run levels and growth in national income. Growth economics studies factors explaining economic growth—the growth in a nation’s per capita income over an extended time frame. They are also used when attempting to assess the differences in per capita output in different countries, growth rates inside and across countries and groups of countries. In addition, they are employed to measure the convergence rates of different economies. Here is where the overall output of goods and services such as the country’s GDP is used to measure the economic welfare, or the amount of wealth a given country produces on average per person. As Joseph Stiglitz has pointed out (Stiglitz, 2019), measuring GDP fails to capture some factors that matter to people’s lives and contribute to their well-being, such as safety, leisure, distribution of income as well as sustainable development and growth per se needs in order to be sustained.

5 Conclusion

All in all, we show that longevity has some profound effects on the changes in returns to education, human capital, and economic growth regardless of the countries and regions in question. The duration and the quality of life of any country’s citizens shape up the economic priorities, the tax collection system, as well as the spending on such important but vulnerable areas as education and healthcare that depend on the state budgets. It is also important to remember that returns to education are also higher in case people live longer and healthier. This helps to foster the creation of the high-quality human capital as well as to preserve it for a longer span of time. All of this might be quite important in the times of the decline in the population due to the falling birth rates in many developed economies. People in those economies tend to live longer but they also tend to settle down in older age in order to start a family. Yet many have few or no children which negatively impacts the population prognoses.

Furthermore, it is a well-known fact that the majority of health-related expenses for any individual falls into the last years of her or his life and might include hospital bills, various expensive treatments, or medicine. The aim of any government is to promote the healthy style of life among the population in order to minimize these costs and to save these money for other purposes.

While low-income and middle-income countries often struggle with malnutrition issues, some middle-income and the majority of high-income countries face the issues of obesity and the health risks it creates. Therefore, the approaches and policies aimed at prolonging the length of healthy and productive lives of the citizens might differ with goals set specifically for each concrete situation.

The impact of education on longevity is also considerable and notable. More investments into human capital means better educated population which can perform better in economic sense and spend more funds on promoting its healthcare and wellbeing.

Therefore, academics, business stakeholders, as well as governmental officials need to support factors leading to the support of the increasing longevity and its beneficial accompanying factors as far as they help to increase the economic growth of the society and increase the prosperity of the whole society.

References

Abulibdeh, A. (2020). Can COVID-19 mitigation measures promote telework practices? Journal of Labor and Society, 23(4), 551–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/wusa.12498

Ahmad, M., & Khan, R. E. A. (2019). Does demographic transition with human capital dynamics matter for economic growth? A dynamic panel data approach to GMM. Social Indicators Research, 142(2), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1928-x

Alfani, G. (2022). Epidemics, Inequality, and Poverty in Preindustrial and Early Industrial Times. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(1), 3–40. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20201640

Ameye, H., & Swinnen, J. (2019). Obesity, income and gender: The changing global relationship. Global Food Security, 23, 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2019.09.003

Baarsch, F., Granadillos, J. R., Hare, W., Knaus, M., Krapp, M., Schaeffer, M., & Lotze-Campen, H. (2020). The impact of climate change on incomes and convergence in Africa. World Development, 126, 104699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104699

Bennett, S., Glandon, D., & Rasanathan, K. (2018). Governing multisectoral action for health in low-income and middle-income countries: Unpacking the problem and rising to the challenge. BMJ Global Health, 3(Suppl 4), e000880. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000880

Bertrand, M., Cortes, P., Olivetti, C., & Pan, J. (2021). Social norms, labour market opportunities, and the marriage gap between skilled and unskilled women. The Review of Economic Studies, 88(4), 1936–1978. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdaa066

Brodeur, A., Gray, D., Islam, A., & Bhuiyan, S. (2021). A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. Journal of Economic Surveys, 35(4), 1007–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12423

Čábelková, I., Abrhám, J., & Strielkowski, W. (2015). Factors influencing job satisfaction in post-transition economies: The case of the Czech Republic. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 21(4), 448–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2015.1073007

Cazalis, V., Loreau, M., & Henderson, K. (2018). Do we have to choose between feeding the human population and conserving nature? Modelling the global dependence of people on ecosystem services. Science of the Total Environment, 634, 1463–1474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.360

Cheng, S., & Song, X. (2019). Linked lives, linked trajectories: Intergenerational association of intragenerational income mobility. American Sociological Review, 84(6), 1037–1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419884497

Chodorow-Reich, G. (2020). Regional data in macroeconomics: Some advice for practitioners. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 115, 103875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2020.103875

Chvátalová, I. (2016). Social policy in the European Union. Czech Journal of Social Sciences, Business and Economics, 5(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.24984/cjssbe.2016.5.1.4

Fang, G., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Long-term impacts of school nutrition: Evidence from China’s school meal reform. World Development, 153, 105854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105854

Ferraro, O., & Cristiano, E. (2021). Family business in the digital age: The state of the art and the impact of change in the estimate of economic value. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(7), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070301

He, L., & Li, N. (2020). The linkages between life expectancy and economic growth: Some new evidence. Empirical Economics, 58(5), 2381–2402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1612-7

Hero, J. O., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Blendon, R. J. (2017). The United States leads other nations in differences by income in perceptions of health and health care. Health Affairs, 36(6), 1032–1040. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0006

Kang, M. Y., Myong, J. P., & Kim, H. R. (2019). Job characteristics as risk factors for early retirement due to ill health: The Korean longitudinal study of aging (2006–2014). Journal of Occupational Health, 61(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12014

Kansiime, M. K., Tambo, J. A., Mugambi, I., Bundi, M., Kara, A., & Owuor, C. (2021). COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development, 137, 105199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199

Kudins, J. (2022). Economic usefulness of older workers in terms of productivity in the modern world. Insights into Regional Development, 4(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.9770/IRD.2022.4.1(3)

Kumar, B., Jensen, M. M., Strielkowski, W., Johnston, J. T., Sharma, V., Dandara, C., Shehata, M., Micarelli Struetta, M., Nikolaou, A., Szymanski, D., Abdul-Ghani, R., Cao, B., Varzinczak, L., Kerman, B., Arthur, P., Oda, F., Bohon, W., Ellwanger, J., Tyner, J., & E., & Murphy. C. (2019). NextGen voices: Science-inspired sustainable behavior. Science, 364(6443), 822–824. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax8945

Lakner, C., Mahler, D. G., Negre, M., & Prydz, E. B. (2022). How much does reducing inequality matter for global poverty? Journal of Economic Inequality. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09510-w

Levasseur, P. (2020). Fat black sheep: Educational penalties of childhood obesity in an emerging country. Public Health Nutrition, 23(18), 3394–3408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002906

Litau, E. Y. (2018). Cognitive science as a pivot of teaching financial disciplines. In Proceedings of the 31st International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2018: Innovation Management and Education Excellence through Vision 2020, 72–80.

Lu, J., Zhang, C., Ren, L., Liang, M., Strielkowski, W., & Streimikis, J. (2020). Evolution of external health costs of electricity generation in the baltic states. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155265

Mackenbach, J. P., Kulhánová, I., Bopp, M., Borrell, C., Deboosere, P., Kovács, K., & De Gelder, R. (2015). Inequalities in alcohol-related mortality in 17 European countries: A retrospective analysis of mortality registers. PLoS Medicine, 12(12), e1001909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001909

Manuel, T., & Herron, T. L. (2020). An ethical perspective of business CSR and the COVID-19 pandemic. Society and Business Review, 15(3), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-06-2020-0086

Mishra, U., & Singhania, D. (2014). contrasting the levels of poverty against the burden of poverty: an Indian case. International Economics Letters, 3(2), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.24984/iel.2014.3.2.1.

Mörk, E., Sjögren, A., & Svaleryd, H. (2020). Consequences of parental job loss on the family environment and on human capital formation-Evidence from workplace closures. Labour Economics, 67, 101911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101911

Moskvina, J. (2022). Work after retirement: The evidence of sustainable employment from Lithuanian enterprise. Insights into Regional Development, 4(2), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.9770/IRD.2022.4.2(4)

Nugroho, A., Amir, H., Maududy, I., & Marlina, I. (2021). Poverty eradication programs in Indonesia: Progress, challenges and reforms. Journal of Policy Modeling, 43(6), 1204–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2021.05.002

Park, S. S., Wiemers, E. E., & Seltzer, J. A. (2019). The family safety net of black and white multigenerational families. Population and Development Review, 45(2), 351. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12233

Reichelt, M., Makovi, K., & Sargsyan, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes. European Societies, 23(sup1), S228–S245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1823010

Setzler, B., & Tintelnot, F. (2021). The effects of foreign multinationals on workers and firms in the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(3), 1943–1991. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjab015

Shan, Y., Ou, J., Wang, D., Zeng, Z., Zhang, S., Guan, D., & Hubacek, K. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 and fiscal stimuli on global emissions and the Paris Agreement. Nature Climate Change, 11(3), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00977-5

Sharma, R. (2018). Health and economic growth: Evidence from dynamic panel data of 143 years. PLoS ONE, 13(10), e0204940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204940

Shulman, J. D., & Geng, X. (2019). Does it pay to shroud in-app purchase prices? Information Systems Research, 30(3), 856–871. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2019.0835

Soummane, S., & Ghersi, F. (2022). Projecting Saudi sectoral electricity demand in 2030 using a computable general equilibrium model. Energy Strategy Reviews, 39, 100787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2021.100787

Stefko, R., Gavurova, B., Ivankova, V., & Rigelsky, M. (2020). Gender inequalities in health and their effect on the economic prosperity represented by the GDP of selected developed countries – Empirical study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103555

Stiglitz, J. E. (2019). Measuring what counts: The global movement for well-being. The New Press.

Strielkowski, W., & Weyskrabova, B. (2014). Ukrainian labour migration and remittances in the Czech Republic. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 105(1), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12052

Strielkowski, W., Zenchenko, S., Tarasova, A., & Radyukova, Y. (2022). Management of smart and sustainable cities in the Post-COVID-19 Era: Lessons and implications. Sustainability, 14(12), 7267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127267

Vela, M. B., Erondu, A. I., Smith, N. A., Peek, M. E., Woodruff, J. N., & Chin, M. H. (2022). Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: Evidence and research needs. Annual Review of Public Health, 43, 477. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103528

Washio, Y., Atreyapurapu, S., Hayashi, Y., Taylor, S., Chang, K., Ma, T., & Isaacs, K. (2021). Systematic review on use of health incentives in US to change maternal health behavior. Preventive Medicine, 145, 106442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106442

Yapp, E., & Pickett, K. E. (2019). Greater income inequality is associated with higher rates of intimate partner violence in Latin America. Public Health, 175, 87–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Guliyeva, A., Nikitina, N.I., Gardanova, Z.R., Ilgov, V.I. (2023). Effects of Longevity on Changes in Returns to Education, Human Capital, and Economic Growth. In: Kumar, V., Kuzmin, E., Zhang, WB., Lavrikova, Y. (eds) Consequences of Social Transformation for Economic Theory. EASET 2022. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27785-6_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27785-6_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-27784-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-27785-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)