Abstract

This chapter presents a social contextual analysis of the ways in which bad life environments can shape the range of ‘psychosis’ behaviors and then what we might do about helping people who have had these behaviors shaped (Boyle and Johnstone, A straight talking introduction to the power threat meaning framework: an alternative to psychiatric diagnosis. PCCS Books, London, 2020; Guerin, Turning psychology into a social science. Routledge, London, 2020c; Johnstone et al., The power threat meaning framework: towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis. British Psychological Society, Leicester, 2018). This will follow a traditional behavior/contextual analysis of searching out (1) the behaviors of interest and then (2) the environments/contexts which shape and maintain these behaviors by (3) analysis of their consequences, outcomes, or functioning. However, this cannot be done in terms of simple or three-term contingencies since the adult human behaviors, environments, and functioning are extremely complex with complex histories. The details will only come from intensive work with individuals and exploring their idiosyncratic functional life contexts, through case study research or therapy, but using the full range of life contexts.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

6.1 Basic Analyses

6.1.1 Behaviors

The psychoses and schizophrenia have long been one of the most contentious of the groupings of ‘mental health’ issues (Bleuler, 1911; Jung, 1907/1960; Luhrmann & Marrow, 2016; Schilder, 1976; Sullivan, 1974). Furthermore, there are also several international groups, many even including psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, requesting that this category be dismantled since it makes little sense (Bentall, 2006; International Society for Psychological and Social Approaches to Psychosis, ISPS, 2017). Here I will ignore the DSM labels anyway since they are fictions, but the behaviors which have been observed and documented in the DSM are clearly not. The people who have had these behaviors shaped are usually suffering and in great pain and confusion.

The current DSM-5 clustering of ‘psychosis’ contains five main groups of very disparate behaviors:

-

Grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia).

-

Negative symptoms (especially diminished emotional expression and avolition—a decrease in motivated self-initiated purposeful activities).

-

Delusions.

-

Disordered thinking (speech)—frequent derailment or incoherence.

-

Hallucinations.

It is also often associated with traumatic and dissociative behaviors, and sometimes concurrent with major mood changes of depression, mania, or both (but labelled ‘schizoaffective’ by the DSM). Thus, even without any form of diagnosis, we can still observe the sorts of behaviors that were previously labeled by this arbitrary category and observe them and the contexts which shape them. We should no longer be guided by the DSM category system, but if they must be categorized, this can be done more functionally (Guerin, 2017, 2020a). There is more in (3) below.

6.1.2 Contexts for ‘Mental Health’ Behaviors

Many people have now proposed that ‘mental health’ behaviors are shaped when people are trying to deal with extremely bad life situations, such as living with traumatic events, abuse, poverty, threats of all sorts, violence, etc. (Boyle & Johnstone, 2020; Frankl, 2006; Guerin, 2020a; Johnstone et al., 2018) and not because of any brain disease, chemical imbalance, or ‘cognitive dysfunction’ (Johnstone, 2014). People are adapting to their bad worlds to get along and survive, but this is not working out well. As we will see below, they are in life situations in which none of their normal behaviors have any real effect to change anything. Behaviors that would normally bring about some change in the world, mostly in the ‘social world’, no longer work. Of particular importance for the group of behaviors listed as ‘psychosis’, language use no longer has the effects it normally has. Language is ‘broken,’ meaning that it no longer gets the outcomes that it normally has through the person’s discursive communities and social relationships. Or to put this better, the person still has all their language skills, but they have no discursive communities that support their talking without punishment or neglect.

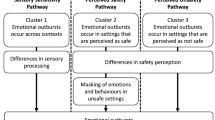

However, we must be clear that such bad life situations shape many different behavioral patterns to cope with, deal with, put up with, or escape from these bad contexts. Figure 6.1 illustrates this broader idea of the bad life situations of many people and some of the diverse behaviors shaped from these. The broadest question for analysis is this: For someone (though no fault of their own) who is trying to live in these bad life conditions, what behaviors are shaped and which more specific life environments shape the more specific different behaviors?

However, when looking at those outcomes of bad life situations which are called ‘mental health’ issues rather than criminal, escapist, exiting, or ‘putting up with’ responses, there are indeed some specific conditions which seem to predict that the ‘mental health’ behaviors will be shaped when trying to deal with such bad life situations. In particular, the following extra conditions are suggested for any contextual analyses of ‘mental health’ behaviors, as opposed to just criminal activities, bullying or exiting:

-

Having weak, bad, or contradictory social relationships and few opportunities for resources.

-

Therefore, being trapped in a bad situation so the other options are not available (such as simple exiting, talking your way out, or bullying your way out).

-

Any alternative behaviors which might be done are blocked, usually by other people.

-

The source or origin of your bad situations cannot easily be seen or observed (so we can further specify which life contexts these are most likely to be; Guerin, 2020a).

-

As a result, some ordinary behaviors which still seem to have some effect on some people some of the time in your life are shaped to become exaggerated or altered; but these are just those behaviors remaining possible with such restrictive worlds.

So, the profile of contexts shaping the ‘mental health’ behaviors is one of very restrictive life contexts with few behavioral options possible and so few effective consequences possible. This is not only just in situations of poverty or abuse, since restrictive life environments with few alternative behaviors can occur in any place in society. In fact, the more wealth a family has, the more they might act to ‘protect’ those family members by restricting their life options, although the wealth can be used to purchase alternative options for the person being restricted so that the ‘mental health’ behaviors do not become shaped.

This means that what have been called the ‘mental health’ behaviors are really behaviors that have been shaped by living in restrictive bad life situations. It turns out (Guerin, 2021) that those behaviors listed under the DSM categories of ‘schizophrenia’ and ‘psychosis’ have been shaped in some of the worst and most restrictive life situations (Bloomfield et al., 2021). But added to this, is that most of these listed behaviors have also been shaped by extremely punishing or neglectful discursive environments.

-

Analyzing the contexts of ‘psychotic’ behaviors as primarily shaped by broken discursive communities.

Before moving on to the more specific behaviors labelled as ‘psychotic’, I will make a few quick points about contextualizing talking and thinking, since such behaviors feature prominently in the ‘psychotic’ behaviors: ‘If we ask ourselves what is it that gives the character of strangeness to the substitutive formation and the symptom in schizophrenia, we eventually come to realize that it is the predominance of what has to do with words over what has to do with things’ (Freud, 1915/1984, p. 206). This is even now clear for the ‘negative symptoms’ (Moernaut et al., 2021).

For a social contextual analysis, language use is just a behavior like any other, although it has some special properties. But the key thing for language use analysis is that language is only shaped and maintained by people, not by anything else in the world. Cats do not shape saying “cat”, only people can do that (even if they sometimes occasion the social behaviors).

So, using words is always about doing things to people. Using language is just a fancy way of doing all of our social behaviors which we could potentially do in other ways, without words. Basically, when we talk about language use, we are talking about managing our social relationships and the outcomes of those relationships. Using language and managing social relationships become synonymous.

The point to take from this is that if there are ‘dysfunctions’ of speech, talking or thinking, then these are really ‘dysfunctions’ of social relationships and getting resources (effects) through social relationships. Typically, this means that “your words are broken”: that is, your words are no longer doing what they should do or have done in the past—there are only punishing consequences or no consequences anymore. Your language is no longer working to do anything, and this is because of social relationship problems. Under these conditions, we see ordinary language uses become exaggerated and distorted, such as occur with the label of ‘psychosis’ but also elsewhere in the DSM.

In this analysis, it is analytically and functionally important that the social relationship problems are occurring over many situations and social relationships. So, it is not that there is a ‘withdrawal’ from one or two people (who might be directly punishing), but a more widespread withdrawal from most social relationships. This could occur in environments in which (1) the larger societal systems are not working for the person (e. g., poverty or patriarchy), (2) many or most of their known social relationships are bad (e. g., abusive and violent families), or (3) they have a very restricted range of social contacts anyway and these are all bad (e. g., highly oppressive or restrictive families). Clearly, the first clinical step for repairing broken language use must be to build some sort of social relationship with such people in which the therapist can be trusted. Trying to focus solely on a quick and language-led recovery (talking therapies) is unlikely to work.

Contextualizing ‘thinking’ is a bit trickier because it is even harder to see the social origins of shaping than for spoken or written language uses. I have suggested that a good way to envisage and contextualize thinking is that it is made of the same language events which occur for talking—all the ways we have been shaped to speak in specific contexts—but our ‘thoughts’ are those which do not get said out loud (Guerin, 2020b, Chapter 4; cf. Skinner 1957). We ‘have’ the language responses in any specific context regardless of whether we say them out loud or not (they have already been shaped in context), and those which are not said out loud comprise what we call our ‘thinking’.

To analyze thinking, therefore, needs additional special forms of observation, analysis, and ‘therapy’. We need to (1) first find out the social contexts in which those discourses have been said out loud in the past, might be said, and with which audiences or social relationships these would be said. Second, (2) we must analyze the contexts under which those discourses are now not said out loud and which constitute thinking. Sometimes this is innocuous, as when we are interrupted, or no one is present. But in other cases, more clinically relevant, language use is not said out loud because there are audiences or social relationships in which some of the talking out loud has been punished or ignored. These cases of being shaped to think language responses instead of saying them out loud include those called ‘repressed thoughts’ by Freud and others.

6.1.3 Analysis of ‘Psychosis’ Behaviors Shaped in Context

What we need to do for analysis, therefore, is to find out how the behaviors of ‘psychosis’ have been shaped by bad life contexts and bad discursive contexts especially. When people are trapped in restrictive and bad life situations, there are numerous everyday behaviors that can get shaped to exaggeration—the whole realm of ‘mental health’ behaviors in fact. Many are done because they are opportunistic, others because there are few alternative behaviors which make any difference at all. People over time usually show many of these different ‘mental health’ behaviors, as well as behaviors to escape, bully or fight their way out, get distracted, or ignore the bad life situation and ‘put up with it’ (Guerin, 2020c). People do not get one ‘disease’ and that is all, as fictionized by the DSM. They are shaped to different and various behaviors over time.

Since the use of language is our primary way of dealing with people and social relationships, we therefore see distortions and exaggeration in the uses of language under restrictive and bad life situations. For example, we observe silence, exaggeration of stories and comments, fantasy stories, etc. With language use messed up, we also therefore can observe reductions in thinking things through, concentration, memory, planning, etc. We can observe exaggerated and ‘strange’ ways of talking about ‘self’. We can also observe people trying to find new audiences for their language use, and in many cases this is seen through such people frequently approaching strangers and trying to talk and tell stories (often catchy exaggerated stories). Talking to strangers might be the only reasonable conversation such a person has all day, even if the stranger soon finds an excuse to leave. But strangers are usually polite for a short time, and there is no responsibility since they will not be encountered again most likely.

It can be seen, then, that having defective discursive communities can lead to a wide range of multiple problems which do not initially seem to bear on the ‘psychotic’ behaviors, including concentration, thinking abilities, coherence of storytelling, coherence of a ‘self’, and selection of audiences. This occurs after years of any use of language being punished, ignored, or constantly opposed.

I will now try to spell this out briefly with each of the five major groups of ‘symptoms’.

6.1.3.1 Grossly Disorganized or Abnormal Motor Behavior

This group of behaviors which is lumped together by the DSM encompasses ordinary behaviors which have been shaped out of the ordinary or exaggerated because they at least have some consequences (albeit dysfunctional usually). Taken directly from the DSM, I mix in here the following DSM listed ‘behaviors’: appear dramatic, emotional, or erratic; appear odd or eccentric, eccentricities of behavior; disorganized or abnormal motor behavior; motor control disrupted from normal; being reckless, impulsivity; increased energy; increased spending; overactivity; repetitive behaviors applied rigidly (Guerin, 2017).

These seem clearly, as a group, to be ordinary behaviors shaped into exaggeration. The general analysis would be that the bad life situations have restricted all possible ‘normal’ behaviors to change it or to exit in some way. These ‘unusual actions’ will certainly have effects, especially in the social contexts, but will not necessarily lead to the bad situation changing. In the case of living in bad societal contexts (poverty, male dominance), they are also not likely to change much. Some of these actions will provide distraction from the person’s bad life contexts, but probably not change much. Some might inadvertently lead to making new social contacts which could eventually help. Strong and weak forms of ‘catatonia’ are also a form of exiting, but also not ones which are likely to help change the bad situations.

6.1.3.2 Negative Symptoms

Negative symptoms are a curious mixture of behaviors which have been disputed over the history of psychiatry (Bleuler, 1912; Jung, 1907/1960). The main ‘behavior’ is the absence of a ‘normal’ behavior. The behaviors include: blunting of affect; poverty of speech and thought; apathy; anhedonia; reduced social drive; loss of motivation; lack of social interest; and inattention to social or cognitive input. The DSM writes:

Negative symptoms account for a substantial portion of the morbidity associated with schizophrenia but are less prominent in other psychotic disorders. Two negative symptoms are particularly prominent in schizophrenia: diminished emotional expression and avolition. Diminished emotional expression includes reductions in the expression of emotions in the face, eye contact, intonation of speech (prosody), and movements of the hand, head, and face that normally give an emotional emphasis to speech. Avolition is a decrease in motivated self-initiated purposeful activities. The individual may sit for long periods of time and show little interest in participating in work or social activities. Other negative symptoms include alogia, anhedonia, and asociality. Alogia is manifested by diminished speech output. Anhedonia is the decreased ability to experience pleasure from positive stimuli or a degradation in the recollection of pleasure previously experienced. Asociality refers to the apparent lack of interest in social interactions and may be associated with avolition, but it can also be a manifestation of limited opportunities for social interactions. (APA, 2013, p. 88)

From a social contextual point of view, keeping in mind the strong functional links given earlier between social relationships and the observed behaviors of thinking, they are all withdrawal or exiting strategies from ‘normal’ social relationships. In this sense, they will be functionally related to depression and catatonia, since they both are similar strategies shaped differently (but using the DSM does not encourage making these links).

Some recent research talking to people who had been labelled as having ‘negative symptoms’ also found that, when put in context, these behaviors were primarily issues of language use rather than problems of the brain (Moernaut et al., 2021). The main behaviors of ‘negative symptoms’ were due to the people not being able to put into words their unusual experiences: ‘…a failure of narratives to account for perplexing experiences participants are confronted with in psychosis’ (p. 1). If still questioned (by a therapist) about their experiences, they tended to employ ‘meta-narratives’, that is, talking about the fact that they could not talk about their experiences and spurious explanations as to why. These authors concluded: “The standard characterization of negative symptoms as a loss of normal functioning should be revised, as this does not match participants’ subjective experiences. Negative symptoms rather represent hard to verbalize experiences. This difficulty of linguistic expression is not a shortcoming of the person experiencing them, but characteristic of the experiences themselves.” Once again, then, what looks like failure of functioning (reduced speech, lack of concentration and planning, etc.) is really about the person’s language no longer working in a normal way because of the bad social relationships they have been subjected to, usually over long periods.

The ‘negative symptoms’ are also common as everyday behaviors, and mostly non-problematic, but in bad environments we see the exaggeration of these otherwise normal ‘withdrawal’ behaviors. If you are in a meeting and get severely criticized, it is likely your language use will also shut down (while you plan revenge; cf. ‘dissociachotic’, Ball, 2020). But ‘negative symptoms’ are ‘generalized’ behaviors which will function in different ways across many different life contexts as ways of (originally, at least) attempting to cope with bad or threatening situations—they are not a response to a specific bad situation such as being punished in one meeting. It is important to note for these behaviors, therefore, that the actual functioning cannot be gleaned by the form or topography of the behaviors, they always need contextualizing. And they could change at any time to another form.

Other behaviors likely to be found with the same people are: crying spells; desperation; feeling overwhelmed; unable to adjust a particular stressor; being awake throughout the night; decreased sleep; sleeping troubles; disturbance of eating, or eating-related behavior; somatic changes that affect the individual’s capacity to function; spending less time with friends and family; staying home from work or school; attention seeking; increased sex drive; increased alcohol and drug use (Guerin, 2017).

There are almost certainly exceptions but in general, time should not be spent on interpreting the ‘meaning’ or ‘sign’ of the particular behaviors in this group, but focus more on:

-

what the person’s overwhelming, general, or bad situation is about and what other responses might help change their environment (“What has happened to you?”)

-

what social relationships do they still have which are present and what the person’s discourses say about these social relationships,

-

the possible generalized audiences for these behaviors (‘generalized other’, ‘social norms’, media, ‘someone’, ‘everyone’, ‘men’, strangers),

-

who is requiring some sort of response be made at all; where is that pressure coming from (it could be from therapists, in fact, demanding that the person put everything into words, “express your feelings”, when they cannot do this; Moernaut et al., 2021).

6.1.3.3 Disorganized Thinking

For the ‘schizophrenic’ behaviors listed by the DSM as ‘disorganized thinking’, I include: slowing down of thoughts and actions; concentration difficulties; consciousness disrupted from normal; memory disrupted from normal; perception disrupted from normal; racing thoughts; rapid speech; disorganized thinking; cognitive or perceptual distortions; preoccupation;

intolerance of uncertainty; repetitive mental acts applied rigidly.

As outlined earlier, for social contextual analysis, any issues with talking or thinking are issues with social relationships. When social relationships are messed up, then our language also get messed up because language only does anything to people. People in bad situations can have their language stop working or functioning because they can no longer get any effects or consequences from talking, or else only punishing effects. Any features of language can then be shaped to become exaggerated or transformed, if this gets at least some effect or change. There are many variations in the DSM, but there are also probably many others with nuanced differences that are worth exploring.

So, the important analysis here is to remember that language use is only shaped through the effects on people, so that when social relationships get bad and other alternatives are not possible, then language ceases to function, at least in the normal ways. With language being perhaps the most frequent behavior through which we all have effects in our worlds, all the functionings of language become undone. This includes most of what are currently called ‘cognitive’ functions such as memory, concentration, ‘processing’, self, beliefs, etc. (Guerin, 2020b). If we think of memory as storytelling in language, then memory will be disrupted in bad life situations in which language is not having any effect on the people around (Janet, 1925/1919). Talking and thinking will be slowed down, and hence ‘concentration’ slowed.

Some forms of ‘disorganized thinking’ in the DSM, but which are functionally related in the above way, in addition to the one labelled ‘disorganized thinking’, are ‘slowing down of thoughts and actions’, ‘concentration difficulties’, ‘consciousness disrupted from normal’, and ‘memory disrupted from normal’. It is suggested that all are shaped from trying to deal with punishing, restricted or negligent social relationships, which means that the language no longer works as it normally would in getting people to do things (help, laugh, bond, entertain, etc.). With heavily punishing audiences for any talk, as seems to be implicated for those who have received labels of ‘schizophrenia’ and ‘psychoses’, we would perhaps expect more of ‘slowing down of thoughts and actions’ and ‘concentration difficulties’. We would also expect that in such socially punishing contexts a lot of talking would be replaced with thinking (Guerin, 2020b, Chapter 3).

To put this all together, when social relationships are massively broken and no longer get any effects, then language will also be broken since that is the main way we get effects in life. This can be replaced by violent or bullying behaviors to have effects, but it also means that language functioning is messed up. Of importance is that if language is heavily or generally punished or no longer gets the common effects, then this will also ‘break’ parts of behavior which are considered important in social life:

-

Self-talk and what this can get us in our social worlds.

-

Memory.

-

Planning and future talk.

-

Increased frequency of engaging strangers in conversation since they are polite for a period in most cases and will not be seen again, so there are no further obligations or responsibly.

-

A strong form of cynicism and noticing of hypocrisy in people’s behavior and talk.

-

Lack of concentration and what looks like ‘slowing down’ of language use.

6.1.3.4 Delusions

It is proposed that similar social relationship issues have shaped the behaviors under theDSM label of ‘delusions’ (Guerin, 2023). This group can also include: dysfunctional beliefs; intrusive and unwanted thoughts; grandiose ideas, grandiosity; hallucinations; recurrent and persistent thoughts. As for before, there will almost inevitably be cross-overs found between all these behaviors as people are shaped into different behaviors by similar and recurring bad life situations.

For social contextual analysis, people’s beliefs are just language use and not something stored or possessed ‘inside’ them (Guerin, 2020c). Our beliefs are shaped by our social relationships and we use our beliefs to do all our regular social behaviors (Guerin, 2020c, Table 4.1). Beliefs are like tools we can use to strategize our social worlds. These strategies are not just to agree with what your significant others believe. For example, you can state your ‘beliefs’ to build a self-identity by using differences to those around you; you can also use beliefs to compete with others around you (Guerin, 2020c, Chapter 4).

For the cases of ‘delusional beliefs’, the person has been shaped into at least one very common way of engaging in social relationships—through the common and ubiquitous use of storytelling (Frank, 2010; Guerin, 2023). However, since this has not worked or been functional in changing anything in the person’s world, it once again becomes exaggerated into certain types of stories with social properties which get attention and which make it difficult to refute. Such stories include rumors, gossip, conspiracy stories, and urban legends (Guerin & Miyazaki, 2006).

The social properties include telling abstract stories, so they are difficult for people to challenge despite any objections by listeners (even therapists report this). They also provide somewhat interesting, engaging, and even entertaining discourses for the person in all parts of life, although this becomes more difficult as they get more exaggerated and extreme. However, with delusional stories to tell, the person can at least engage in some social interactions which potentially could help change their bad life situations. However, these probably work best for new audiences and those who are strangers, rather than the same delusions being told over to the same known people. It must also be remembered that any aversiveness from poor stories being told repeatedly can also function as yet another type of exiting or withdrawal strategy—a way of getting away from people or having them back off.

6.1.3.5 Hallucinations (Auditory)

Both visual hallucinations and auditory hallucinations (voice hearing) are related to delusions, dysfunctional beliefs, intrusive and unwanted thoughts, grandiose ideas, grandiosity, and recurrent and persistent thoughts. They all pertain to language and imagery responses, including thinking, becoming exaggerated under very bad life situations. I would also include panic attacks in this functional group even though they are remote from the others within the DSM.

For the case of auditory hallucinations, which includes voice hearing, it is easier to see the analysis. I have proposed earlier already that thinking is the same as talking but is under further external contexts (usually punishing) such that they are not said out loud. It is also clear that hearing music, voices, and other sounds are ‘normal’ behaviors, but wrongly talked about as originating from inside the head. We ‘normally’ have a dominant, command or ‘me’ voice, but this is shaped by all the discourses, conversations, dialogues, media, television, etc. around us constantly in everyday life for all our life. Our talking and arguing with those commonly around us also figures prominently in all this.

So, it is no wonder that under extreme bad life situations when a person’s language is not working to have any effect and get things done, these other behaviors will also be exaggerated. And what is then heard as an ‘auditory hallucination’ (hearing voices or noises) will originate from the many discourses around us as responses which are not said out loud. If we normally have a conflict with someone, and cannot say out loud all the things we are shaped to, then we will ruminate over this for a time afterwards until it is resolved (Kheng & Guerin, 2020)

An anthropological study by Luhrmann et al. (2015) and Luhmann (1912) shows this clearly. They talked to people who hear voices in India, Ghana, and the United States and interviewed for some of the social relationship contexts for the voices.

Broadly speaking the voice-hearing experience was similar in all three settings. Many of those interviewed reported good and bad voices; many reported conversations with their voices, and many reported whispering, hissing or voices they could not quite hear. In all settings there were people who reported that God had spoken to them and in all settings there were people who hated their voices and experienced them as an assault. Nevertheless, there were striking differences in the quality of the voice-hearing experience, and particularly in the quality of relationship with the speaker of the voice. Many participants in the Chennai and Accra samples insisted that their predominant or even only experience of the voices was positive – a report supported by chart review and clinical observation. Not one American did so. Many in the Chennai and Accra samples seemed to experience their voices as people: the voice was that of a human the participant knew, such as a brother or a neighbor, or a human-like spirit whom the participant also knew. These respondents seemed to have real human relationships with the voices – sometimes even when they did not like them. This was less typical of the San Mateo sample, whose reported experiences were markedly more violent, harsher and more hated… In general the American sample experienced voices as bombardment and as symptoms of a brain disease caused by genes or trauma... Five people even described their voice-hearing experience as a battle or war, as in ‘the warfare of everyone just yelling’. (p. 42)

More than half of the Chennai sample (n = 11) heard voices of kin, such as parents, mother-in-law, sister-in-law or sisters. Another two experienced a voice as husband or wife, and yet another reported that the voice said he should listen to his father. These voices behaved as relatives do: they gave guidance, but they also scolded. They often gave commands to do domestic tasks. Although people did not always like them, they spoke about them as relationships. One man explained, ‘They talk as if elder people advising younger people’. A woman heard seven or eight of her female relatives scold her constantly. They told her that she should die; but they also told her to bathe, to shop, and to go into the kitchen and prepare food. Another woman explained that her voice took on the form of different family members – it ‘talks like all the familiar persons in my house’. Although the voice frightened her and sometimes, she claimed, even beat her, she insisted that the voice was good: ‘It teaches me what I don’t know’. (p. 43)

6.1.3.6 Hallucinations (Visual)

Visual hallucinations are likely to co-occur with delusions, dysfunctional beliefs; intrusive and unwanted thoughts; auditory hallucinations; grandiose ideas, grandiosity; recurrent and persistent thoughts.

People in everyday life report imagery, some more than others, and it is usually very persuasive, direct, and impactful. More so than hearing or talking. The same analyses therefore apply that when trapped in very bad life situations, strong visual hallucination imagery can appear, shaped by the change it usually incurs.

In this way the shaping and effects of visual hallucinations are like those of hearing voices and panic attacks. They are all normal behaviors shaped by bad life situations. They do not contain a message, as is sometimes claimed, but do signal that the life situation is out of control. In earlier times (premodern, imagery was probably more frequently used, since language has become the dominant behaviors in modernity. Seeing visions was also more common, therefore, and likewise signaled that something was wrong with the community’s life situation that needed changing. So indirectly they probably contained another sort of message as they do now.

6.2 How to Support People Who Have Been Shaped into the ‘Psychosis’ Behaviors?

Having looked at the behaviors shaped when trying to live in bad life situations, and the specific behaviors shaped by the extra ‘mental health’ conditions, we can finally look at what might be done to change such shaped behaviors. I want to separate out two parts of this: how to respond to someone with these behaviors, and how to attempt to change or lessen such behaviors.

6.2.1 How to Respond Within a Social Relationship or ‘Therapeutic Alliance’

What is typically done with these ‘disorders’ is to support the person by distraction, forced removal, or capacity-reducing drugs, and hope that over time their bad situations will change (which they can do, of course). Often, they have bureaucratic forms to deal with as well. None of these are helpful for people in such situations.

From the analysis here, the support person must remember that the person is used to non-effectual social behavior and language use, so the best strategy is finding ways to show that what the person is saying does indeed have some effects on the listener (typically the therapist to start). This is not done through asking a lot of questions (“When did these delusions first occur?”), nor just reflecting back what they tell you (“You seem to be feeling very confused”). Better is to be clear that their words are beginning to get some of the usual effects of people using language. Even for those of us outside of these life bad situations, being interrogated or being asked a lot of questions about our own conduct, history, and the like is an unusual discourse in everyday life and is at least mildly punishing.

So, one better strategy is to just listen and then be clear about what effect the person’s words are having on you (Guerin et al., 2021). In doing this, one must be ‘authentic’ or honest, since the people will easily know if it is being made up—they have had a lifetime of observing fake responding. Getting them to talk about their experiences or history, or anything they wish, is the best way to proceed. [But one must also beware of the neoliberal shaping of modern therapy to be quick and efficient when doing this.] Once the person has talked and you have listened and shown you have been affected, then other things can be done, but often that by itself is enough.

6.2.2 How to Change the Behaviors

The ideal task of therapy from the social contextual approach is to analyze the person’s bad life situations and try to change those life situations or find a different strategy for the person which actually works to have some life effects. Just changing the actual behaviors alone as they appear, as typically done in CBT, will not be enough if the person will remain in their same bad environments. Moving the person to a completely new life world might even be necessary (e.g., Haley, 1973). Also, of importance is finding activities and especially new social connections in which they can have an effect on people or make a difference, since this has not been possible for some time in their lives.

To put this succinctly, the message is to: fix the person’s bad life situations, don’t try and fix the person. And to do this by responding that is sensitive to their long histories of poor outcomes from any use of language.

If we look back to Fig. 6.1, it suggests that there are at least three ‘layers’ of treatment for life issues arising from trying to live in bad situations.

-

Level 3 For Level 3, there are attempts made to directly change the behaviors shaped by the bad life situations in partnership with the person (always), without changing the life situation itself. If the person is doing ‘delinquent’ behaviors, then try and stop or change those behaviors. If the person is having anxious thoughts, then try and stop, block, or replace those thoughts. Typical procedures here are done through clinical psychology (CBT), behavior modification, coaching into alterative behaviors, educational programs, and many more methods going back a long time (Janet, 1925/1919).

-

Level 2 The interventions or treatments called Level 2 are attempts to just help people cope with their bad life situations; that is, put up with it or cushion the bad effects. Counselling, therapy, and clinical psychology all do this, as does social work for people with ‘mental health’ behaviors and other behaviors listed in Fig. 6.1 (violence, drugs, bullying, crime). Psychiatric medications are the same in that they placate people and make it easier for them to put up with their ‘symptoms’, but psychiatric drugs do not ‘cure’ anything and have more troublesome side effects including difficulties with eventual withdrawal. Recreational drugs can have the same Level 2 outcomes as well.

-

Level 1 These are attempts to directly change the person’s bad life world. That is, go into the person’s world and work with them to change their bad life situations. This rarely happens in psychiatry and clinical psychology (with a few exceptions), and such clinicians are usually not allowed to do this professionally. Some social workers do most of this, as do other ‘care workers’ and community helpers.

For many of those with ‘mental health’ behaviors, that is, who have had behaviors shaped through bad life situations, the above is sufficient. However, when dealing with those who have been shaped into behaviors in the ‘psychosis’ label, often it is nearly impossible to go in and change the ‘home’ life situation. There is often crime, abuse, drug use, etc., for which many others are involved, making this difficult or impossible to change. In such cases, it becomes necessary to work with the person to create new life contexts and reduce the impact of the person’s original life situation. This is easier for discursive communities than the more physical problems of normal life (abuse, poverty, etc.). I will deal with creating new discursive communities in more detail below.

In reality all three levels are needed. Regardless of whether Levels 1 or 3 are implemented, people need to be socially and materially supported and cared for throughout (Level 2). Many bad life situations are extremely difficult to change, so supporting the person to put up with their predicaments until the bad situations resolve themselves ‘naturally’ is probably what a large number of purported ‘cures’ are really doing. If you have some form of therapy or treatment over 1–2 years, frequently the bad life situation will change during that period anyway.

A curious feature of contextual approaches is that when a context changes, the behaviors which have been shaped do not become ‘cured’ or ‘stopped,’ but they simply disappear and do not occur. When you are seated in front of a piano, then your playing behaviors occur. When the piano is absent then the behaviors simply disappear (unless there is another context for piano playing present). Your piano playing does not get ‘wiped out’, ‘erased’, or ‘cured’.

Table 6.1 shows some of the therapy discourses used with the medial model of the outcomes being sought. Table 6.1 also shows some of the terms that are used for contextual approaches when changes occur. It is important to note that you often do not wish for the behavior to completely be erased in any case, since there will likely be contexts in life when those behaviors are functional. We do not want people in therapy to have crying erased, just attuned to new contexts.

6.2.3 Dealing with Language Use Issues

The general treatment of ‘psychosis’ behaviors we have seen follows along the same lines. But those who have such behaviors shaped are usually in extreme bad life situations, so Level 2 is necessary throughout. Level 1 and 3 treatments often are difficult to do even in partnership with the person. But we have seen that a lot of the symptoms are language-based, which really means they are social relationship-based. We have also seen that the specific behaviors are not so important and should not be overinterpreted. So the main thrust is to work on Level 1 and change the bad discursive life worlds such people are living in.

The main part of interventions, therefore, from a social contextual approach is to find some activities, probably not related to their ‘symptoms’, which allow the person to act in the world and have some effects through using their language. These do not have to be positive or pleasurable effects, as we have seen from their symptoms. Having effects on other people is probably the best, but initially this can be difficult to manage. Music and art therapy can function in this way (Guerin, 2019a, b; Killick, 2017). Similar events occur in newer treatments for voice hearers (Romme & Escher, 2000). So instead of focusing on the ‘delusions’ or trying to refute them (CBT), find ways with the person for them to engage with new listeners in other types of storytelling that have ‘normal’ effects. Many of the newer ‘social’ treatments for ‘psychosis’ are probably doing this inadvertently (Haddock & Slade, 1996; Meaden & Fox, 2015; Mullen, 2021; Putman & Martindale, 2022; Ruiz, 2021a, b).

So, because the behaviors labelled as ‘psychosis’ are commonly language-based, finding ways to allow the people with ‘psychosis’ behaviors to have effects on people using their language would be the best step. Devise activities in which the person can talk, so that this talking actually has consequences on another person, agreeing, obeying, bonding, etc. Talking about things unrelated to their shaped language behaviors is probably the best. That is, do not discuss their delusions, etc. but other things in life, and other forms of storytelling (Frank, 2010).

Basically, their social relationships and the consequences which can be gained from social relationships need to be repaired (fix the person’s bad discursive situations, don’t try and fix the person). Some therapists probably do this incidentally from talking to people, but it could be done in much better ways with real trust. The therapist needs to let the person with ‘psychosis’ behaviors have real effects with consequences(effects) through other people, this is what has been missing in their lives. But ironically, clinical training frequently requires the clinician to not show any signs that the person has affected them in any way.

Finding ways to support a person into developing such language-use-with-effects can occur within therapy in many ways. It is usually done inadvertently by most therapists, but a lot more could be done by not just asking questions and listening to answers but by arranging so that the person can achieve outcomes with their language use. Asking questions and getting answers in therapy is usually only for the benefit (effect) of the therapist. This might be as simple as the person asking the therapist a question and getting an answer, which is often not allowed in therapy. Many therapies almost certainly do some of these without it being explicit (Haddock & Slade, 1996; Meaden & Fox, 2015; Mullen, 2021; Putman & Martindale, 2022; Ruiz, 2021a, b).

If one looks through the sociolinguistic research, one can find a myriad of potential methods for this. As one example, ‘adjacency pairs’ is a sociolinguistic term for common pairs of statements in everyday conversation where the first has a reliable or common outcome or effect: questions have the effect of getting an answer; thanking gets “you’re welcome”; a greeting gets a return greeting effect; a request gets a fulfilment; etc. The point of these is not to learn what people commonly do but to begin using language, possibly with new audiences than those who have shaped the ‘psychosis’ behaviors, and get some effects occurring. This is what has been missing. Therapists need to become much more sensitive or attuned to what effects language has, and how that applies within therapy to those they are supporting (Guerin et al., 2021).

We can go beyond the ‘therapeutic alliance’ as a potential breeding ground for getting effects or outcomes for language use and begin to involve other people outside of the therapy situation. Those shaped into ‘psychosis’ behaviors typically do not need communication training or language instruction—they have presumably learned all that before. What they lack are supportive discursive communities. This can be done by helping the person to find new groups and social relationships where their talking is more effective. The outcomes of talk do not have to be all kindness, positive and understanding; rather, the talk needs to let the person have effects on other people, to get things done with their language in the way we all do. Self-help groups are important, but there is a myriad of other groups who could provide this basic resource, community, and special-interest groups. If your talk always receives only positive and affirming replies, such as in some self-groups, this can wear thin, as it does in everyday conversations. There is much sociolinguistic research on other forms of language use which can have effects, such as politeness, and directives (Guerin, 1997).

But the other main sensitivity is about what is said out loud and what is ‘thought’. From a long time of being punished, thinking (talking but not out loud) is prevalent, and so another goal is to increase out loud talking. Again, this does not just mean to get the person saying anything out loud or trying to talk about ‘feelings’ or difficult topics, but just to have their discourses receive outcomes or effects when out loud, rather than merely being thought when they get no outcomes. So, what is talked about in this way is almost irrelevant, and if nonsensitive topics were done more, this would likely increase more rapidly. Forcing someone to talk about what is difficult or impossible to say out loud (Guerin, 2020a, Chapter 7; Moernaut et al., 2021) is counterproductive to having them learn to talk and get reasonable or useful outcomes. Again, ironically, therapists are taught to only talk about and address serious personal issues, and things that are difficult to even say, when conducting therapy.

Eventually, then, the person with new audiences and getting effects other than punishment and neglect when they talk will begin reestablishing their talking about plans, memories, ‘self’, and improve their concentration and remembering.

6.2.4 Building a Discursive Life History

Finally, if the person is willing to talk about their history and context, we can now add another type of finding out their contextual history. This is to ask directly about the discourses and outcomes of those discourses in their lives. Table 6.2 gives some ideas of what can be asked. Remember that this is really about the person’s social relationships, and what they have been able to do with those audiences in the past.

References

Ball, M. (2020). Dissociachotic: Seeing non psychosis. Paper presented at A disorder for everyone! Challenging the culture of psychiatric diagnosis and exploring trauma informed alternatives. Cornwall, UK.

Bentall, R. P. (2006). Madness explained: Why we must reject the Kraepelinian paradigm and replace it with a ‘complaint-orientated’ approach to understanding mental illness. Medical Hypotheses, 66, 220–233.

Bleuler, E. (1911). Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. International Universities Press.

Bleuler, E. (1912). The theory of schizophrenic negativism. NY: The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company. (Nervous and mental disease monographs series, Number 11).

Bloomfield, M. A. P., Chang, T., Wood, M. J., et al. (2021). Psychological processes mediating the association between developmental trauma and specific psychotic symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 20, 107–123.

Boyle, M., & Johnstone, L. (2020). A straight talking introduction to the power threat meaning framework: An alternative to psychiatric diagnosis. PCCS Books.

Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. University of Chicago Press.

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Freud, S. (1915/1984). The unconscious. (In the Penguin freud library volume 11) : Penguin Books.

Guerin, B. (1997). Social contexts for communication: Communicative power as past and present social consequences. In J. Owen (Ed.), Context and communication behavior (pp. 133–179). Context Press.

Guerin, B. (2017). How to rethink mental illness: The human contexts behind the labels. Routledge.

Guerin, B. (2019a). What does poetry do to readers and listeners, and how does it do this? Language use as social activity and its clinical relevance. Revista Brasileira de Análise do Comportamento, 15, 100–114.

Guerin, B. (2019b). Contextualizing music to enhance music therapy. Revista Perspectivas em Anályse Comportamento, 10, 222–242.

Guerin, B. (2020a). Turning mental health into social action. Routledge.

Guerin, B. (2020b). Turning psychology into social contextual analysis. Routledge.

Guerin, B. (2020c). Turning psychology into a social science. Routledge.

Guerin, B. (2021). Contextualizing the ‘psychotic’ behaviors: A social contextual approach. In J. A. Díaz-Garrido, H. Laffite Cabrera, & R. Zúñiga Costa (Eds.), Terapia de aceptación y compromiso en psicosis: Aceptación y recuperación por niveles (ART) (Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis: Acceptance and Recovery by Levels (ART)) (pp. 533–550). Ediciones Pirámide (Spanish translation).

Guerin, B. (2023). Delusions as storytelling gone wrong in bad life situations: Exploring a discursive contextual analysis of delusions with clinical implications. University of South Australia: Unpublished paper.

Guerin, B., & Miyazaki, Y. (2006). Analyzing rumors, gossip, and urban legends through their conversational properties. The Psychological Record, 56, 23–34. [Translated into Spanish in: Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 35, 257–272].

Guerin, B., Ball, M., & Ritchie, R. (2021). Therapy in the absence of psychopathology and neoliberalism. University of South Australia: Unpublished paper.

Haddock, G., & Slade, P. D. (Eds.). (1996). Cognitive-behavioural interventions with psychotic disorders. Routledge.

Haley, J. (1973). Uncommon therapy: The psychiatric techniques of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Norton.

ISPS. (2017, July). ISPS Liverpool declaration. http://www.isps2017uk.org/making-real-change-happen

Janet, P. (1925/1919). Psychological healing: A historical and clinical study. George Allen & Unwin.

Johnstone, L. (2014). A straight talking introduction to psychiatric diagnosis. PCCS Books.

Johnstone, L., Boyle, M., Cromby, J., Dillon, J., Harper, D., Kinderman, P., et al. (2018). The power threat meaning framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis. British Psychological Society.

Jung, C. G. (1907/1960). The psychogenesis of mental disease. Princeton University Press.

Kheng, C., & Guerin, B. (2020). “I just can’t get that thought out of my head”: Contextualizing rumination as an everyday discursive-social phenomenon and its clinical significance. University of South Australia: Unpublished paper.

Killick, K. (Ed.). (2017). Art therapy for psychosis: Theory and practice. Routledge.

Luhrmann, T. M. (1912). When God talks back: Understanding the American evangelical relationships with God. Vintage Books.

Luhrmann, T. M., & Marrow, J. (Eds.). (2016). Our most troubling madness: Case studies in schizophrenia across cultures. University of California Press.

Luhrmann, T. M., Padmavati, R., Tharoor, H., & Osei, A. (2015). Differences in voice-hearing experiences of people psychosis in the USA, India and Ghana: Interview-based study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(1), 41–44.

Meaden, A., & Fox, A. (2015). Innovations in psychosocial interventions for psychosis: Working with the hard to reach. Routledge.

Moernaut, N., Krivzov, J., Lizon, M., Feyaerts, J., & Vanheule, S. (2021). Negative symptoms in psychosis: Failure and construction of narratives. Psychosis, 14, 1–10.

Mullen, M. (2021). The dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook: Manage your emotions, reduce symptoms and get back your life. New Harbinger.

Putman, N., & Martindale, B. (2022). Open dialogue for psychosis: Organising mental health services to prioritise dialogue, relationship and meaning. Routledge.

Romme, M., & Escher, S. (2000). Making sense of voices: A guide for mental health for professionals working with voice-hearers. Mind Publications.

Ruiz, J. J. (2021a). ACT de grupo para personas con experiencias psicóticas. In J. A. Díaz-Garrido, H. Laffite Cabrera, & R. Zúñiga Costa (Eds.), Terapia de aceptación y compromiso en psicosis: Aceptación y recuperación por niveles (ART) (Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis: Acceptance and Recovery by Levels (ART)) (pp. 261–288). Ediciones Pirámide (Spanish translation).

Ruiz, J. J. (Ed.). (2021b). FACT de Grupo. Integrando ACT y FAP de Grupo. Ediciones Psara.

Schilder, P. (1976). On psychoses. International Universities Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Prentice Hall.

Sullivan, H. S. (1974). Schizophrenia as a human process. Norton.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Guerin, B. (2023). Contextualizing ‘Psychosis’ Behaviors and What to Do About Them. In: Díaz-Garrido, J.A., Zúñiga, R., Laffite, H., Morris, E. (eds) Psychological Interventions for Psychosis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27003-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27003-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-27002-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-27003-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)