Abstract

Education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) students living in remote communities has long been seen as an intractable problem. Ten years of concerted effort under Closing the Gap and related policy initiatives has done little to improve outcomes beyond small, incremental improvements. Programs and strategies promising much have come and gone, and most have quietly gone by the wayside. This apparent failure leaves the context of remote education ripe for the picking. If we can demonstrate what works and why, it may provide an answer to the problem. This systematic review aims to uncover what research in the ten years from 2010 to 2020 reveals about what does and does not make a difference to outcomes for students. The review identified 36 papers that provide strong evidence to show what is and is not effective. The review also found several issues that have little or no evidence and which could be the subject of more research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The outcomes of education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First NationsFootnote 1) students from remote communities have been cause for some concern. Over the last few decades, multiple reports have highlighted the gap in achievement results for remote students (Harris, 1990; Northern Territory Department of Education, 1999; Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 2000; Wilson, 2014; Northern Territory Department of Education, 1986; Watts & Gallacher, 1964). Each year in Australia, the Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap Report (e.g. Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2020) highlights failures, deficits, and statistics that show little or no change in the results.

Against a bleak picture of limited evidence and a history of apparent failures, this systematic review sought to find out, based on recent credible research and evaluation evidence, what contributes to better outcomes for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. This chapter brings an earlier study (Guenther et al., 2019) which reported data from the period 2006 to 2017 up to date with evidence from the period 2010 to 2020.

Methodology

Review Question

The question used for this systematic review of the literature was “What factors contribute to educational outcomes for Indigenous students from remote communities?”

Factors were conceptualised as influencers of positive or negative outcomes, for example leadership, pedagogy, engagement, health-related factors, and parent participation. Educational outcomes were conceptualised as any positive or negative personal, academic, social product of schooling. They included educational attainment, citizenship, success or failure, identity, equity, well-being, and empowerment. Students were conceptualised as young people from pre-school (excluding childcare) through primary and secondary years of education. Their “schooling” was also understood in terms of participation in boarding schools, hostels, elementary, residential, or independent schools. The focus of this review was on remote Australian Indigenous students; those identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students from remote and very remote parts of the nation. “Remote” students were understood in terms of geographic isolation, from homelands, or from what is sometimes referred to as a “red dirt” context. The review did not consider aspects of rural or regional education.

Databases and Publication Sources

The following electronic databases were searched using available library search tools: EBSCO Education Complete, A+ Education, Eric, ProQuest, PsycInfo, Scopus, and Web of Science. The author’s own EndNote library was searched as well.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

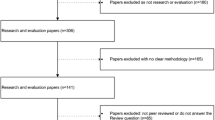

The procedure for identifying articles and their critical appraisal follows the methods detailed by (Lowe et al., 2019) and in Chap. 2. Database searches supplemented by the lead author’s own reference library yielded 1153 articles (after duplicates were removed). Of these 57 came from the lead author’s own library and 1091 came from database searches. A total of 733 papers were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed above, leaving 420 papers. If the paper’s abstract or other bibliographic fields did not describe research, evaluation, or empirical evidence, it was excluded. Similarly, if they did not mention or describe a methodology, papers were filtered out of the included studies. If papers were not peer reviewed or did not respond to the review question, they were excluded. Application of filtering processes reduced the number of included articles from 420 to 53 (see Fig. 12.1).

Critical Appraisal

For each paper, six criteria were selected. Criteria were chosen to reflect aspects of quality in qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies. In the review of each paper, a score of 1 was given if the criterion was fully met, 0.5 if the criterion was partially met and 0 if it was not met satisfactorily. Scores were calculated for each paper reviewed. Those that did not achieve a score of at least 4 out of a possible 6 were rejected. From the 53 papers, 17 were excluded, leaving 15 quantitative, 15 qualitative, and six mixed-methods papers.

Methodological Issues: Quantitative Studies

One of the major concerns with some quantitative studies that use standardised instruments is that they often fail to consider the philosophical standpoints of minority groups they are measuring. The assumptions about what defines “success” are challenged in papers by Guenther et al. (2014b), Guenther (2013), and Guenther et al. (2015). The other point to note, which arises from quantitative studies, is that analysis is often conducted where young people are currently engaged at school drawing on their results. This limitation is discussed in the studies on Abecedarian programs (Page et al., 2019; Wolgemuth et al., 2011) and the paper by Dunstan et al. (2017) on affective engagement.

Methodological Issues: Qualitative Studies

Qualitative methodologies are generally built on paradigms of subjective reality. In the case of the studies reviewed here, many of the studies explored peoples’ perceptions. It is noteworthy that in many cases, the perceptions of local people differ from those of non-locals (Guenther et al., 2015; Guenther et al., 2014a). Therefore, success can mean one thing to one group of people and another thing to others.

Findings and Discussion

Limitations of Papers Versus Theses

One feature of this review is the number of papers that are based on post-graduate studies or theses. Thirteen of the 36 papers were based on eight separate post-graduate studies. Seven papers were completed theses. Only one of the post-graduate studies (Wilson et al., 2018) was quantitative and two employed mixed methods (Nutton, 2013; Hunter, 2015). In most cases, these studies ranked highly in the critical appraisal assessments. One reason for the higher scores is the greater opportunity to fully explain methods, findings, and implications, together with ethical considerations and theory. Some of the journal articles scored lower, not because of the quality of the study, but because of the length constraints of journals or book chapters.

What Is Not Discussed in the Papers

There are several important issues that are not discussed in the papers. None of the papers discussed policy issues in any depth, though the paper on Direct Instruction implementation by Guenther and Osborne (2020) does raise concerns about the ethics of policy implementation that results in harm to students. Funding, somewhat related to policy, is discussed more as a contextual factor than a causal issue for outcomes. Research on the impact of funding for educational outcomes does not appear in the included papers. Systemic issues are seldom discussed in any detail in the papers. For example, no papers focus specifically on workforce development. Nor is there a paper that focuses on the impact of leadership or pre-service teacher preparation. These are all important issues that can have an impact on outcomes for students.

None of the papers discussed remote schooling outcomes as employment or economic participation. McInerney et al. (2012) and Guenther et al. (2014a) discuss aspirations for work, but not actual outcomes. Guenther et al., (2014b) draw a link from employment to educational outcomes, but do not make the connection the other way around. None of the papers discussed schooling outcomes in terms of language and culture, though Guenther et al. (2015) point to community perceptions of success in terms of first language learning.

What Factors Contribute to Educational Outcomes for Indigenous Students from Remote Communities?

The outcomes of schooling are defined by the included papers in several ways. We found seven clusters of outcomes. Several papers describe outcomes in academic terms, often as literacy and numeracy (Guenther, 2013; Biddle & Cameron, 2012; Lietz et al., 2014). A second cluster relates to well-being, often discussed in terms of physical health such as hearing loss (Su et al., 2019) and related issues such as racism and “teasing” (Guenther et al., 2018). A third cluster describes aspirations emerging from and contributing to education, particularly related to motivations and choices (Parkes, 2013; Parkes et al., 2015; McInerney, 2012; McInerney et al., 2012). A fourth cluster described outcomes in terms of equity, including aspects of access, opportunity, and justice (Silburn et al., 2014). A fifth cluster points to participation as an outcome, with elements of attendance, engagement, and retention (Dunstan et al., 2017; Hewitt & Walter, 2014). A sixth cluster relates to identities, related to confidence and alignment (or misalignment) to ontological positions (Fogarty, 2010; Gaffney, 2013). Finally, a small cluster of outcomes is described as relational, particularly in terms of social networks (Mander, 2012; Biddle & Cameron, 2012). Outcomes then are many and varied. When referring to “success”, few papers specifically defined what this was (except e.g.Guenther et al., 2015), but implied was a combination of the above outcomes.

Moving now to factors that do not contribute substantially to positive outcomes, the papers raise questions about the following approaches. Firstly, remoteness is mostly not considered to influence outcomes. Several studies challenge this (for example Guenther, 2013; Guenther, 2015; Biddle et al., 2012; Hewitt & Walter, 2014), and while some studies did find correlations between remoteness and outcomes, some showed positive relationships, such as the study by Dunstan et al. (2017) which showed remoteness was associated with greater affective engagement. Secondly, programmatic solutions to remote teaching or pedagogy are highly dependent on other factors. Even Abecedarian programs (Page et al., 2019; Wolgemuth et al., 2011), which were found to be effective in raising phonological awareness, were dependent on teacher attitudes and acceptance of professional learning. Some, such as Direct Instruction (Guenther & Osborne, 2020), fail to show improvement. Thirdly, of concern is the number of studies that report problems with boarding schools and programs (Guenther et al., 2016; Benveniste et al., 2015a, 2015b; Mander, 2012; O’Bryan, 2016; Hunter, 2015). The evidence presented here should raise concerns for policy advisors and funders, who invest significant resources into boarding. Fourthly, we can also be confident from this review that standardised testing in the form of NAPLAN will not demonstrate what works well for remote students where “vocabulary items tested may not have been within the life experiences of children in more remote areas” (McLeod et al., 2014, p. 129). Standardised testing at best masks the positive outcomes of students and at worst supports racist or assimilationist expectations of education (Guenther, 2015). Nevertheless, as Guenther and Osborne (2020) demonstrate in their paper on Direct Instruction, analysis of NAPLAN results can demonstrate the ineffectiveness of policies implemented in remote contexts. Fifthly, we can be confident that poverty or so-called socio-economic disadvantage is not in itself a barrier to outcomes (Guenther, 2013; Silburn et al., 2014). The studies that do show a link between low socio-economic status and academic performance reflect a range of complementary factors, such as access to resources or the products of other social challenges in communities such as violence, substance abuse, and the malaise associated with lost identities leading to mental illness. Finally, we can be confident that attendance strategies do not work (Guenther, 2013). There is no evidence in the papers we reviewed to demonstrate that they work to improve attendance and there is no evidence to show that they work to improve academic performance.

What then can we be confident about in determining the factors that do contribute positively to better outcomes for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students?

Parent and community involvement emerged as a theme in many of the studies as a predictor of and indicator of success in remote schools. The evidence suggests that parents who can support their children at school will be more likely to see their children succeed at school (Guenther et al., 2014b; Hewitt & Walter, 2014). Community involvement in schooling implies a degree of ownership and suggests an alignment of values, identities, and knowledge systems. Coupled with this, the evidence points to the importance of local employment as local teachers, assistants, and other staff (Wolgemuth et al., 2011; Helmer et al., 2011). These local staff act as a bridge between the community, its families, and the school (Guenther et al., 2015). We noted earlier that attendance strategies do not work. However, when students are engaged in learning they learn, whether in or out of school, particularly where it is culturally responsive (Fogarty, 2010). Pedagogies that work with students and support their views of the world are fundamentally important to success (Gaffney, 2013). The attendance “problem” in remote schools points to disengagement and agency. If we accept that local understandings of success are important, then we must accept that local appropriate curriculum and pedagogies, fit for the context, are also important (Rioux et al., 2018). First language literacy is an important predictor of second (or English) language literacy success, demonstrating the need for bilingual programs in remote communities (Wilson et al., 2018). The importance of history was highlighted by Povey and Trudgett (2019). They argue “that listening to Aboriginal lived experiences and perceptions of western education from the past will better inform our engagement with the delivery of equitable educational opportunities for Aboriginal students in remote contexts in the future” (p. 75).

Finally, students’ health and well-being are important priorities for learning (Su et al., 2019; Franck et al., 2020). Without attention to these important factors, the mistakes of schooling reported earlier—particularly in the boarding school literature—will be repeated.

Significance for Policy

We noted earlier that issues of policy research did not emerge in the systematic review. However, many of the studies which we reviewed were a direct result of policies implemented by governments over the last 10 years. “Closing the Gap” has dominated the landscape of remote education interventions in this ten-year period. The Closing the Gap targets and measures focus on a handful of issues related to schooling: attendance, early years learning, and Year 12 completion along with literacy and numeracy. Much of the focus of research then has been on understanding factors that will contributing to improvements in these areas. One of the important outcomes of the studies we examined is that many of the assumptions of policy advisors and politicians are challenged. The assumption that improved attendance is the causal factor that will lead to better outcomes is one myth that has largely been debunked. What we have found is a range of factors that would be a better focus of policy design and implementation. These factors include the need for local employment in schools, the role that health and well-being play in learner engagement, the significance of first language learning, of culturally responsive pedagogy and curriculum, and taking account of local histories. The outcomes that attention to these aspects of remote education might bring may not include higher attendance, but they will almost certainly include better engagement in learning, improvements in community capability, better governance, and more socially just education for remote communities.

There are some cautions in the findings too. The evidence of investment in programs that have increased harm to students is of concern. Boarding school initiatives, which have taken young people out of their communities as a solution to the Year 12 achievement gap, have been demonstrated to cause harm, and much of the research that is now coming into the public domain is concerned with how to ameliorate that failure. The failure of Direct Instruction is another cautionary finding, which points to ethical concerns when vested interests control policy agendas despite evidence showing failure.

Finally, the narrow focus on research directed at four closing the gap outcomes leaves other issues such as Aboriginal workforce development, school leadership, governance, pre-service teacher preparation, teacher retention, post-school pathways, and issues related to curriculum and pedagogy largely untouched by research. Additionally, while we have seen some research on the nexus between health, well-being, housing, and education in this systematic review, the challenge for policy implementers is to bring these together in practice. How do we, for example, ensure that health professionals and educators work together to address issues of hearing impairment, which was reported in one of the papers. And how do we ensure that education leads to economic benefit beyond the school years? It is one thing to have the evidence of what works and what does not work; it is another to act on it.

Conclusion

This systematic review has explored the factors contributing to outcomes for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. Across the many issues addressed in 36 included studies, the complexity of the context becomes apparent. Many of the studies examined reported on what fails to produce outcomes—or what produces negative outcomes. The review raises questions about whose outcomes matter. “Outcomes” to many commentators within the hegemonic power structures that define education policy are tightly configured around literacy, numeracy, retention, transition to higher education, and transition to jobs. There are many other outcomes that this review uncovers. These are clustered under headings of equity, health and well-being, aspirations, participation, identities, and relationships.

The factors that contribute to improved outcomes—particularly those defined from a community perspective—are focused on parent and community involvement, attention to health, well-being, local employment, appropriate curriculum, and pedagogies and strategies that build engagement in learning. While the review has uncovered much evidence, there remain important gaps in the literature. For example, the contributions of leadership, funding, policy, workforce development, and pre-service teacher preparation are largely ignored. The economic outcomes of remote education are also largely ignored, as are the outcomes of language and culture.

So what does this all mean for parents of students and teachers in remote schools? First and foremost, the findings show how important parent and community engagement is. Schools must therefore find ways of including parents in supporting schools and community members more generally must be engaged in governance and teaching processes. Culture and context is also fundamentally important in remote schools. Learning needs to be relevant and culturally responsive—and there is good evidence from this review to show the importance of incorporating language and culture through teaching and learning both in and outside the classroom. The review also highlights the need to be vigilant against one-size-fits-all approaches which may work elsewhere, but do not work in remote contexts.

Notes

- 1.

We use the term “First Nations” here to refer to Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, except when quoting literature where “Indigenous” or a particular language group may be described.

References

Benveniste, T., Dawson, D., & Rainbird, S. (2015b). The role of the residence: Exploring the goals of an aboriginal residential program in contributing to the education and development of remote students. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 44(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2015.19

Benveniste, T., Guenther, J., Dawson, D., & Rainbird, S. (2015a). Deciphering distance: Exploring how Indigenous boarding schools facilitate and maintain relationships with remote families and communities. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education annual conference, Fremantle.

Biddle, N., & Cameron, T. (2012). Potential factors influencing indigenous education participation and achievement. Research report. National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Biddle, N., Cameron, T., & National Centre for Vocational Education, R. (2012). Potential factors influencing indigenous education participation and achievement. Research report. National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Dunstan, L., Hewitt, B., & Tomaszewski, W. (2017). Indigenous children’s affective engagement with school: The influence of socio-structural, subjective and relational factors. Australian Journal of Education, 61(3), 250–269.

Fogarty, W. P. (2010). Learning through country: Competing knowledge systems and place based pedagogy. Australian National University.

Franck, L., Midford, R., Cahill, H., Buergelt, P. T., Robinson, G., Leckning, B., et al. (2020). Enhancing social and emotional wellbeing of aboriginal boarding students: Evaluation of a social and emotional learning pilot program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 771. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/3/771

Gaffney, R. (2013). English as a distant language: An investigation of teachers’ understanding. Australian Catholic University.

Guenther, J. (2013). Are we making education count in remote Australian communities or just counting education? Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 42(2), 157–170.

Guenther, J. (2015). Analysis of national test scores in very remote Australian schools: Understanding the results through a different lens. Transforming the Future of Learning with Educational Research (pp. 125–143). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-7495-0.ch007.

Guenther, J., Disbray, S., & Osborne, S. (2014b). Digging up the (red) dirt on education: One shovel at a time. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues (Special Edition), 17(4), 40–56.

Guenther, J., Disbray, S., & Osborne, S. (2015). Building on “Red Dirt” perspectives: What counts as important for remote education? Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 44(2), 194–206.

Guenther, J., Disbray, S., & Osborne, S. (2018). “It’s just teasing”: Responding to conflict in remote Australian schools (Educational Psychology 3500). Child and adolescent wellbeing and violence prevention in schools, 118–128.

Guenther, J., Lowe, K., Burgess, C., Vass, G., & Moodie, N. (2019). Factors contributing to educational outcomes for First Nations students from remote communities: A systematic review (journal article). Australian Educational Researcher, 42(2), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00308-4

Guenther, J., Milgate, G., O’Beirne, P., & Osborne, S. (2014a). Aboriginal and torres strait islander aspirations and expectations of schooling in very remote Australian schools. AARE Conference Proceedings, 1–4 December, Queensland University of Technology Kelvin Grove Campus, Brisbane.

Guenther, J., Milgate, G., Perrett, B., Benveniste, T., Osborne, S., & Disbray, S. (2016, November 30). Boarding schools for remote secondary Aboriginal learners in the Northern Territory. Smooth transition of rough ride? Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education Annual Conference, Melbourne.

Guenther, J., & Osborne, S. (2020). Did DI do it? The impact of a programme designed to improve literacy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in remote schools. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2019.28.

Harris, T. (1990). Talking is not enough: A review of the education of traditionally oriented Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory. Office of the Minister for Education, the Arts and Cultural Affairs. Available at: http://www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/handle/10070/264712. Accessed February 2017.

Helmer, J., Bartlett, C., Wolgemuth, J. R., & Lea, T. (2011). Coaching (and) commitment: Linking ongoing professional development, quality teaching and student outcomes. Professional Development in Education, 37(2), 197–211.

Hewitt, B., & Walter, M. (2014). Preschool participation among Indigenous children in Australia. Family Matters, 95, 41–50. https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/fm95e.pdf

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (2000). Education Access: National Inquiry into rural and remote education. Available at: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/pdf/human_rights/rural_remote/Access_final.pdf. Accessed August 2015.

Hunter, E. K. (2015). One foot in both worlds: Providing a city education for Indigenous Australian children from a very remote community: a case study. Charles Sturt University.

Lietz, P., Darmawan, I. G. N., & Aldous, C. (2014). Indigenous and rural students: Double whammy or golden opportunity? Evidence from South Australia and around the world. (Paper presented at the Australian Council for Educational Research. Research Conference. Quality and equity: What does research tell us? 3–5 August 2014, Adelaide Convention Centre, South Australia: Conference proceedings).

Lowe, K., Tennent, C., Guenther, J., Harrison, N., Burgess, C., Moodie, N., et al. (2019). ‘Aboriginal Voices’: An overview of the methodology applied in the systematic review of recent research across ten key areas of Australian Indigenous education (journal article). Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00307-5

Mander, D. J. (2012). The transition experience to boarding school for male Aboriginal secondary school students from regional and remote communities across Western Australia. Edith Cowan University.

McInerney, D. M. (2012). Conceptual and methodological challenges in multiple goal research among remote and very remote indigenous Australian students. Applied Psychology, 61(4), 634–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00509.x

McInerney, D. M., Fasoli, L., Stephenson, P., & Herbert, J. (2012). Building the future for remote indigenous students in Australia: An examination of future goals, motivation, learning and achievement in cultural context. Handbook on Psychology of Motivation: New Research (pp. 61–84).

McLeod, S., Verdon, S., & Kneebone, L. B. (2014). Celebrating young Indigenous Australian children’s speech and language competence. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29, 118–131.

Northern Territory Department of Education. (1986, June). Aboriginal education in the Northern Territory: A situation report, June 1986. Department of Education.

Northern Territory Department of Education. (1999). Learning Lessons—An independent review of Indigenous education in the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Department of Education. Northern Territory Government.

Nutton, G. D. (2013). The effectiveness of mobile preschool (Northern Territory) in improving school readiness for very remote Indigenous children. Charles Darwin University.

O’Bryan, M. (2016). Shaping futures, shaping lives: An investigation into the lived experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in Australian boarding schools. University of Melbourne.

Page, J., Cock, M. L., Murray, L., Eadie, T., Niklas, F., Scull, J., et al. (2019). An abecedarian approach with aboriginal families and their young children in Australia: Playgroup participation and developmental outcomes (Article). International Journal of Early Childhood, 51(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00246-3

Parkes, A. (2013). The dreams of mobile young Aboriginal Australian people. Bachelor of Arts Sociology Honours Thesis.

Parkes, A., McRae-Williams, E., & Tedmanson, D. (2015). Dreams and aspirations of mobile young Aboriginal Australian people. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(6), 763–776.

Povey, R., & Trudgett, M. (2019). There was movement at the station: Western education at Moola Bulla, 1910–1955 (Article). History of Education Review, 48(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/HER-10-2018-0024

Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2020). Closing the Gap Report 2020. Australian Government. Available at: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf/closing-the-gap-report-2020.pdf. Accessed February, 2020.

Rioux, J., Ewing, B., & Cooper, T. J. (2018). Embedding aboriginal perspectives and knowledge in the biology curriculum: The little porky. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 47(2), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2017.12

Silburn, S., McKenzie, J., Guthridge, S., Li, L., & Li, S. Q. (2014). Unpacking educational inequality in the Northern Territory. Paper presented at Quality and equity: What does research tell us? 3–5 August 2014, Adelaide Convention Centre, South Australia.

Su, J. Y., He, V. Y., Guthridge, S., Howard, D., Leach, A., & Silburn, S. (2019). The impact of hearing impairment on Aboriginal children’s school attendance in remote Northern Territory: A data linkage study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12948

Watts, B. H., & Gallacher, J. D. (1964). Report on an investigation into the curriculum and teaching methods used in Aboriginal schools in the Northern Territory, to the Honourable C. E. Barnes, Minister of State for Territories. Darwin, N.T.

Wilson, B. (2014). A share in the future: Review of Indigenous Education in the Northern Territory. Available at: https://www.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/229016/A-Share-in-the-Future-The-Review-of-Indigenous-Education-in-the-Northern-Territory.pdf (Accessed: August 2018).

Wilson, B., Quinn, S. J., Abbott, T., & Cairney, S. (2018). The role of Aboriginal literacy in improving English literacy in remote Aboriginal communities: An empirical systems analysis with the Interplay Wellbeing Framework. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-017-9217-z

Wolgemuth, J., Savage, R., Helmer, J., Lea, T., Harper, H., Chalkiti, K., et al. (2011). Using computer-based instruction to improve Indigenous early literacy in Northern Australia: A quasi-experimental study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(4), 727–750. http://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/view/947/223

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Guenther, J., Lowe, K., Burgess, C., Vass, G., Moodie, N. (2023). Making a Difference in Educational Outcomes for Remote First Nations Students. In: Moodie, N., Lowe, K., Dixon, R., Trimmer, K. (eds) Assessing the Evidence in Indigenous Education Research. Postcolonial Studies in Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14306-9_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14306-9_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14305-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14306-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)