Abstract

Waqf organisations are not only known as a religious organisation, but also as a non-profit organisation (NPO) that are responsible and accountable to manage endowment funds and properties of the donors (waqif) to address socio-economy issues. Despite their growing prominence, they have not yet achieved their fullest potential in exerting their accountability to stakeholders. This could be attributed to the limited disclosure on how they measure and report their social impact and values. Disclosing appropriate information on the impact of waqf can garner support and increase confidence from the public to continue to invest in waqf. This paper attempts to investigate how waqf organisations can learn from NPO’s experience in the adoption of performance measurement systems (PMSs) that address the issue of accountability to their stakeholders. On the back of these issues, this study attempts to propose the need for social impact measurement (SIM) to measure performance to enhance organisations’ accountability towards their stakeholders. The study adopts an integrative or critical review of the literature in areas of accountability, PMS for NPOs and waqf organisations, and analysing the missing link that waqf organisations can learn from the practice of NPOs, particularly in the introduction of SIM. It is hoped that this paper is able to provide significant insight on the importance of SIM to be introduced in waqf organisations in efforts to discharge accountability to all stakeholders.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Non-profit organisation (NPO)

- Third-sector organisation (TSO)

- Waqf organisation

- Performance measurement system (PMS)

- Social impact measurement (SIM)

1 Introduction

Waqf is one of the Islamic financial instruments known for its contribution in developing Islamic nations in the past, meeting the basic survival needs of the poor and needy despite in a mostly informal structure (Mahomed 2017). Under waqf, an owner dedicates an asset, either movable or immovable, for permanent societal benefit, while the beneficiaries perpetually enjoy its usufruct and/or income. In recent years, waqf organisations are also known as non-profit organisations (NPOs) that take responsibility and accountability in managing endowment funds and properties in Muslim countries (Adnan et al. 2013). NPOs are considered an alternative approach initiated by a group of people to meet the needs and solve issues of specific groups in the community and represent many types of organisations. These organisations include educational institutions such as universities and schools, religious institutions, healthcare centres, local, state and federal governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), charitable institutions, trade unions, humanitarian aid agencies, foundations, cooperatives, civil rights organisations, political organisations and parties, and others that include volunteers and the third sector (Frumkin 2005; Moxham 2009; Valentinov 2011).

Waqf organisations are highly influential to the society and economy, and therefore can no longer be perceived as simply religious organisations (Arshad and Haneef 2016; Islahi 2003; Sadeq 2002). Despite the growing importance and expectations given to waqf organisations, they have not yet achieved their fullest potential in exerting their accountability to stakeholders (Arshad and Zain 2017; Yaacob 2006). According to Ibrahim and Ibrahim (2013), waqf organisations in Malaysia have been facing recurring issues on accountability and have even received recommendations from the country’s Auditor General’s office to continuously make efforts to improve the management and development of waqf. According to Mujahid and Adawiah (2019), the unrealised potentials and lack of trust towards Islamic social finance (ISF) institutions, including those of waqf organisations, are due to the limited disclosure on how Islamic finance institutions measure and report their social impact and values. Disclosing appropriate information on the impact of waqf can be used as a means to garner support and increase confidence from the public to continue to invest in waqf (Ramli et al. 2018).

Many organisations have used various performance measurement systems (PMSs) to discharge their accountability to their stakeholders. Some of the PMS frameworks which have been adopted or proposed for waqf organisations are similar to those for NPOs and public administration. One of the most prevalent PMSs in practice is the Balanced Scorecard (BSC). It looks into four measures namely financial, customers, internal processes and learning and growth. As time evolves, Ramli et al. (2018) proposed a Shariah-based waqf performance measurement model by integrating the BSC framework with Shariah principle. In another study, Noordin et al. (2017) developed a contingency framework for assessing performance of waqf institutions to include three important elements namely, input, output and outcome; as well as four significant performance dimensions relevant to waqf organisations namely efficiency, social effectiveness, maqasid shariah, and sustainability and growth. The authors also then proceeded to draw eight necessary steps that can serve as guidelines for waqf institutions in designing their own comprehensive PMS.

This paper looks into how waqf organisations can learn from NPO’s experience for the adoption of PMS. This may potentially address the issue of accountability to their stakeholders. While addressing these issues, this study attempts to propose the need for social impact measurement (SIM) to measure performance to enhance organisations’ accountability towards their stakeholders. The study adopts a thorough and critical review of the literature in areas of accountability, PMS for NPOs and waqf organisations and analysing the missing link that waqf organisations can learn from the practice of NPOs.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 thoroughly reviews related works of literature about accountability, PMS and SIM in NPOs. Section 3 describes the methodology used for this study. Section 4 analyses the data and presents the research findings, which includes relating the concept of conventional accountability with Islamic accountability, the missing link in PMS in waqf, and a proposal for SIM for waqf organisations. Finally, Sect. 5 presents the conclusion of this research and suggestions for future study.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Accountability in Non-profit Organisations (NPOs)

Accountability is defined as the fact or state of taking responsibility for one’s decisions or actions whereby one can explain when the need arises (Oxford)). It is the means by which individuals and organisations report to a recognised authority (or authorities) and are held responsible for their actions (Edwards and Hulme 1996). The concept encompasses the relationship between accountor and accountee (Cameron 2004; Gray and Jenkins 1993; Ibrahim 2000; Rahman 1998). In addition, accountability also means that organisations make a commitment to respond to and balance stakeholder needs in its decision-making processes and activities, and commit to deliver (Lloyd et al. 2007). This is deemed important particularly for NPOs in maintaining public confidence and financial support by giving an account of their activities. According to Ebrahim (2003), accountability should not be seen as a reactive response to pressure such as regulation but should also be a proactive effort in sustaining public confidence in the sector (Ebrahim 2003).

Accountability can be demonstrated through many ways, including financial reporting and non-financial reporting such as social impact measurement (SIM) reporting. The level of accountability differs depending on the type of stakeholders, their interests, and the type of organisation. According to Edwards and Hulme (1996), NPOs could either have “downwards accountability”, which refers to the organisations’ partners, beneficiaries, employees, and advocators; or “upwards accountability”, which refers to their trustees, contributors, and respective local authorities. Ebrahim (2003) has suggested that accountability involves many parties, namely the donors interested in the fund utilisation and management, the beneficiaries who are the receiver of the services, and the internal stakeholders within the organisation itself.

2.2 Performance Measurement in Non-profit Organisations (NPOs)

The overview in Sect. 2.1 on accountability becomes the backbone of performance measurement in NPOs due to the pressure to be accountable to various stakeholders. Cameron (2004) considers accountability the foundation of management and governance of any organisation. In recent years, NPOs have drawn attention from society, particularly in the west, mainly due to the increased demand and motivation by the people in searching for alternative avenues to contribute to the society (Ebrahim and Rangan 2010). This development and acceptance of similar organisations, including other third sector organisations (TSOs) besides NPO into the mainstream economy require systematic monitoring mechanisms to ensure their accountability in performance social activities (Hyndman and Jones 2011).

Performance measurement systems (PMS) in NPOs are not quite the same as in for-profit organisations. In fact, they could be even more complex given their focus on social mission and values, which considers not only organisational efficiency and viability, but also the social impact of the organisation (Treinta et al. 2020). Ospina et al. (2002) recognise that many of the PMS tools, models and frameworks have been developed with for-profit companies in mind, which may or may not be suitable for NPOs. However, despite the challenges, NPOs continue to find ways to put in place a reliable PMS for their stakeholders. NPOs, similar to TSOs, are under immense pressure to portray great governance and prove their capability to convert funds into impactful activities while avoiding unnecessary wastages. At the end of the day, donors are not only interested to find out about the quality of their activities, but rather how efficient are NPOs in using those funds to meet the intended purpose. PMS generally can transform an organisation’s strategy and mission into measurable key performance indicators that oversee organisational decisions (Lima and Costa 2008; Waal 2007).

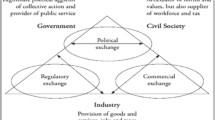

Treinta et al. (2020) in their recent study on design and implementations of PMS in NPOs concluded a framework that puts together the main factors that influence the design-implementation aspects of PMS. This framework was identified via an exhaustive bibliometric and network analysis of literature review. Design-implementation factors are reclaimed from a content analysis of the paper set, where the most frequent terms were classified into three main groups: (i) social factors; (ii) stakeholder-related factors; and (iii) managerial factors. Accountability is the summary of this finding is shown in the Fig. 1 below:

Source Treinta et al. (2020)

Framework for the factors that influence the design-implementation of performance measurement

2.3 Social Impact Measurement in Non-profit Organisations (NPOs)

Recent discussions on the advancement of charity bodies have revolved around capturing and measuring their social impacts and values to the public (Arvidson and Lyon 2014; Polonsky and Grau 2010; Teasdale et al. 2012; Westall 2009). This includes the introduction and emphasis put on social impact measurement (SIM) system in NPOs.

SIM, in general, is designed to identify changes in social impacts that result in the activities of the organisation or stakeholder (Epstein and Yuthas 2014). Most organisations usually measure the outputs produced, for example, the number of meals served to underprivileged children. However, SIM assesses the ultimate impacts of those outputs on the society and the environment, for example, the quality of the meal to children’s health.

TSOs, which NPOs also fall under, have long adopted performance measurements for their organisations due to the great pressure received to demonstrate their good governance and ability to manage charitable funds, as well as being a means to discharge their accountability in order to ensure continued receipt of funding, thus safeguarding the sustainability of their operations (Noordin et al. 2017). Performance measurement in TSOs has initially been dominated by quantitative methods, mainly concerning the practice of financial reporting. However, this has evolved over the years to include non-quantitative methods too.

Some keywords that have been used to conceptualise the construct of SIM include social value (Moss et al. 2011; Santos 2012), social performance (Husted and Salazar 2006; Mair and Marti 2006; Nicholls 2008), social returns (Emerson 2003), social return on investment (Hall et al. 2015; Nicholls et al. 2009), and social accounting (Nicholls 2009), which, although similar, could represent distinct constructs.

Maas and Liket (2011) had categorised social impact measurement methods adopted by various NPOs into the following (Table 1):

According to Maas and Liket (2011), several methods have been developed by, or for, NPOs or NGOs such as SROI, OASIS, SCBA and LEM. Other methods like SRA, ACAFI, TBL, MIF, and BACO are more prominent in for-profit companies. Some methods can be adapted in other organisations that they are initially intended for, as can be seen with the SROI. It was initially developed for NPOs but for-profit companies are benefitting from this method too. Meanwhile, according to Gonul and Senyuva (2020), some of the most used SIM methods in social enterprises that are not in the table above are Cost-Benefit Analysis or lately called Social Cost Benefit Analysis, Social Accounting and Basic Efficiency Resource (BER) Analysis. Due to the nature of subjectivity of SIM depending on the mission of each organisation, the methods can be used interchangeably.

While NPOs do not like to compete against each other for funds, they must put in efforts to communicate the impact and value derived from their activities to remain sustainable in receiving funds from donors (Arvidson and Lyon 2014). As such, NPOs must be aware of how their donors assess their social value, including the non-financial benefits to wellbeing across multiple stakeholders (Cunningham and Ricks 2004). Besides donors, the pressure from authorities becomes another factor why there is a growing interest amongst NPOs to measure their social impact in order to receive recognition of being accountable to all parties.

3 Research Methodology

This study undertakes an integrative or critical review of the literature to obtain secondary data. In general, a literature review allows the researchers to build a solid foundation for the study by exploring the concept of accountability, performance measurement and SIM in NPOs. Drawing from the experiences of NPOs gathered from literature in NPO sector, this paper’s objective is to explore and provide a thorough and critical review of accountability and PMS in waqf organisations to identify areas in the current practice that need further enhancement. This includes the proposal of SIM as a means to measure performance to enhance the accountability of the organisations towards its stakeholders. For newly emerging topics such as SIM in waqf organisations, the purpose of such integrative review is not to cover all articles ever published on the topic but rather to gain insights and combine perspectives from various fields to create initial or preliminary conceptualisations and theoretical models (Snyder 2019).

4 Findings and Discussions

4.1 Accountability and Performance Measurement in Waqf Organisations: Lessons from NPOs

The idea of conventional accountability described in the literature review aligns with Islam. Accountability in Islam continues to enhance what has already been promoted by conventional accountability. In addition to the worldly and material status often focused on by the West, Islamic accountability comes with a realisation that everyone will be answerable to Allah in the Hereafter (Masruki and Shafrii 2013). Islam believes that accountability stems from the concept of amanah (trust) and khalifah (vicegerent). A man’s primary accountability should be to answer to Allah as narrated in the second chapter of the Quran, verse 284 which means: “To Allah belongs all that is in the heavens and on earth, whether you show what is in your minds or conceal it, Allah will call you to account for it”, while a man’s secondary accountability is towards is other human beings based on the contract established between them Sulaiman et al. (2009). Expanding this concept to waqf organisations, the relationship between the waqif (donor) and the mutawalli (trustee) is ultimately built upon this concept of accountability in Islam, aimed at ensuring the intended impact of social services are responsibly and adequately made. The financial and non-financial resources given to the mutawalli to meet this goal is a form of trust that waqf management must uphold as a khalifah, which will be accounted for in the Hereafter. Furthermore, Kamarubahrina et al. (2019) is of the opinion that this expectation for transparency and accountability becomes more pertinent due to the trend in waqf management which has moved from land to cash waqf and even to digital money.

Since waqf’s nature and primary purpose is similar to NPOs to benefit the society (Ihsan and Ayedh 2015; Ramli and Muhamed 2013), waqf organisations may adopt and apply similar concept and measurement of performance for NPOs. Due to limited literature on performance measurement in waqf, Noordin et al. (2017) had drawn similarities between the waqf and TSOs specifically in terms of their fundamental vision, foundation principles, deliverables, end goals, growth as well as the development and challenges faced by both with regards to PMS.

Generally, prior studies had focused on measuring the performance of waqf organisations based on the adoption of quantitative methods such as financial accounting and ratios (Abdul Rahman et al. 1999; Ihsan and Ibrahim 2011; Shaikh et al. 2019; Siraj 2012; Sulaiman and Zakari 2015) and balanced scorecards embedded with shariah principles (Ramli et al. 2018). This is to ensure that all activities performed are Shariah-compliant and assessed based on the Shariah principles. However, more researchers have also begun to consider qualitative or non-financial elements in measuring performance. For example, besides looking at just financial perspective like financial ratios, Arshad and Zain (2017) also considered non-financial aspects in measuring the performance of waqf organisations in Malaysia like input, output and outcome. In another study, Arshad et al. (2018) proposed an additional perspective of the non-financial measurements by including relevant perspectives of network. The proposal was inspired by a study by Chongmyoung Lee and Nowell (2015) on PMS for NPOs who identified inputs, organisational capacity, outputs, outcomes, public value accomplishments and network/institutional legitimacy as the perspectives that can be adopted to measure and conceptualise the performance of NPOs. Noordin et al. (2017) also attempted to look at qualitative methods of PMS in waqf. In their study, they had 1) conceptually designed a contingency framework for assessing the performance of waqf institutions based on the elements of input, output and outcome, on four dimensions of Maqasid Shariah, efficiency, social effectiveness and, sustainability and growth; and 2) outlined guidelines for waqf organisations to design their own comprehensive PMS.

4.2 The Missing Link in the Current PMS of Waqf Organisations

Despite the importance and expectations given to waqf organisations, they have not yet achieved their fullest potential in exerting their accountability to stakeholders (Arshad and Zain 2017; Yaacob 2006). According to Mujahid and Adawiah (2019), the unrealised potentials and lack of trust towards Islamic social finance (ISF) institutions, including those of waqf organisations, are due to the limited disclosure on how Islamic finance institutions measure and report their social impact and values.

One way to address this is for waqf organisations to exercise transparency to discharge accountability to the stakeholders through social impact measurement (SIM). Unfortunately, as discussed in Sect. 4.1 earlier, the performance of waqf organisations has been conventionally and predominantly assessed using quantitative methods. While the quantitative approach is essential, the performance measurement of waqf organisations should also focus on other qualitative measures, through which emphasis is given on realising their social mission and thereafter, communicating the social value that the organisation creates in a clear and consistent manner. These qualitative approaches have also started to gain more attention in recent years. Disclosing appropriate information on the impact of waqf can be used as a means to garner support and increase confidence from the public to continue to invest in waqf (Ramli et al. 2018). Failure to do so may result in a significant reduction in waqf assets with an unwanted impact on the socio-economic development of the Ummah (Arshad et al. 2018).

The concept of perpetuity in an important element in waqf in order to be able to generate continuous income for the needy and solve socio-economic issues. A good plan and governance are indeed crucial to discharge accountability to various stakeholders including donors and beneficiaries (Ramli and Muhamed 2013). In Malaysia, the role of waqf has received remarkable attention from the government. This is demonstrated in several special allocations in the country’s 9th to 12th Malaysia Plans, as well as in the establishment of Department of Awqaf, Zakat and Hajj under the Prime Minister’s Office in 2004. The department’s primary mission is to strengthen the institutions of Awqaf, Zakat and Hajj for socio-economic development through governance and service delivery system. However, despite the recognition given, Arshad and Haneef (2016) and Noordin et al. (2017) argue that waqf could still be under-recognised in the mainstream economy, and potentially underestimate its true potentials. The absence of a systematic method to measure, demonstrate and communicate its social impacts could be one of the possible reasons for this lack of recognition (Noordin et al. 2017). Not only that. waqf organisations are still not able to demonstrate whether or not they are achieving their fundamental purpose of existence (maqasid waqf) based on higher objectives of shariah (maqasid shariah). As such, waqf organisations are expected to exert transparency and accountability to stakeholders with regards to their performance in achieving the underlying objectives of waqf, which cover the overall maslahah (benefits) for the society. This includes the preservation of waqf assets, ie. ensuring the good condition of waqf properties (Ibrahim and Khan 2015); and safeguarding the perpetuity of waqf by ensuring the sustainability of economic activities, equitable distribution of wealth and contribution to the growth of civilisation (Al-Mubarak 2016).

Waqif have long been pressuring for a comprehensive performance measurement system for waqf from the mutawalli, or waqf managers and operators (Noordin et al. 2017). This is to ensure that they properly discharge their responsibility and accountability in managing the waqf assets to benefit the intended beneficiaries. The lack of a systematic tool has contributed to the inability to measure social impact of waqf as well as the incapability to analyse areas that need improvement. This call of action is also consistent with the growing realisation that there is a demand for better ways to account for the social, economic and environmental value that results from financial activities (J. Nicholls et al. 2009) including one for waqf institutions (Noordin et al. 2017). A SIM framework may prevent the risk of diverting these instruments from their original purpose and may provide a comprehensive measurement of financial and non-financial indicators.

Today, there is an increasing realisation for waqf as a potential tool to contribute to a just society. According to Sadeq (2002), waqf has the potential to eradicate poverty by not only sustaining non-profit generating activities in social aspects such as health and education, but also increasing access to physical facilities, resources and employment. According to Ebrahim (2003), the notion of accountability is inseparably intertwined with the notion that accounting should supply a range of information to satisfy user needs. This information shall not be limited to only financial information, but also non-financial.

4.3 The Need for Social Impact Measurement (SIM) in Waqf Organisations

As mentioned in Sect. 2.3, SIM helps to identify the social impacts as a consequence of the activities by the organisation (Epstein and Yuthas 2014). Waqf organisations have been known to measure the collections and spendings, ie. input and output, but the actual impact remains unknown. Based on the authors’ critical analysis of the literature, no studies on SIM in waqf organisations have been done so far and therefore it is imperative for it to be introduced and discussed now. There are many reasons for social impact to be measured by organisations. According to Epstein and Yuthas (2014), measurement of impact allow for the following (Fig. 2):

Source Epstein and Yuthas (2014)

Reasons for impact measurement

Measure for Learning.

The measurement allows for organisations to understand their performance level and validate whether or not their assumptions of certain activities and strategies lead to the desired results. According to Mujahid and Adawiah (2019), the fundamental reason of existence and purpose of Islamic finance is to create sustainable social impact that provides betterment for the whole universe (rahmatan lil ‘alāmīn). The authors argue that the ‘formalist conundrum’ of Islamic finance has restricted the role of Islamic financial institution (IFI) practices to focus on Shariah-compliance, whilst neglecting its social value and purpose. Therefore, they must measure their performance and test the assumptions of whether or not they are fulfilling their fundamental values to confirm if their actions have created positive social impact.

Measure for Action.

Once the above is understood, the organisation can guide their actions and decide on necessary changes or interventions to improve the impact. Waqf organisations will have to be clear in describing the constructs and what they represent, thus translating the underlying maqasid shariah into actionable and measurable results. This clarity will help them understand what is being measured and decide which metrics to use. Thereafter, organisations may report their impact internally, which helps them communicate what is valued within the organisation and align priorities of the organisation.

Measure for Accountability.

Finally, SIM allows for an important measure of accountability, which is the main focus of this paper. Stakeholders, either as a funder or beneficiary, are interested in the impact made by the organisations. SIM verifies the impact achievement and provides stakeholders with an opportunity to assess their funding or investments based on their satisfaction. Reporting impact can also increase the trust of stakeholders in waqf organisations, leading to an enhanced relationship and collaboration between them in the future. The more values they could see from the impact reporting, the more motivated they will be to participate in the funding of the organisations. Arshad and Zain (2017) also agree that the impact measurement will assist waqf organisations to discharge their accountability to the relevant stakeholders. The results of the measurement will demonstrate to stakeholders the success or failure of organisations in achieving their intended goals (Helmig et al. 2014). Furthermore, the impact measurement will also display the effectiveness and efficiency of relevant administrators in utilising the appropriated resources (Arshad et al. 2018).

Finally, the introduction of SIM in waqf organisations is timely now more than ever due to the need to measure and verify their social impact to the society as part of fulfilling its fundamental objectives. As stated by Mujahid and Adawiah (2019), SIM is a great tool to test whether ISF organisations have contributed positively towards society and to verify whether they are fulfilling the fundamental reason for their existence. The traditional unidimensional yardstick which focuses only on financial measures is no longer sufficient. SIM will assist waqf organisations to identify where they stand, where they want to be (their goals), and how to get there. In addition, SIM will produce strategic assets for institutions by collecting relevant data (Reynolds et al. 2018) and help to set informed benchmarks for further developments (Arshad et al. 2018).

5 Conclusion

Despite the growing demand for a proper accountability on performance of waqf organisations by different types of users, it is found that the current practice has not been standardised and does not cover its entire aspects of performance as a religious as well as a voluntary organisation. Therefore, this paper aims to draw lessons from the concept of accountability and the adoption of performance measurement of NPOs that waqf organisations can learn from. This study also goes through a thorough and critical review of the literature on performance measurement of waqf institutions in order to identify areas in the current practice that need to further enhancement in the area of accountability. It is found that relying solely on financial reporting and accounting ratios is not enough to exert accountability to its stakeholders, forcing NPOs and waqf organisations to look deeper into the quality of their services and its impacts on society beyond just financial performance. Finally, an emphasis of introducing SIM in waqf organisations is made to enhance the accountability of the organisations towards its stakeholders.

Various analysis tools for assessing social performance and impact have been explored and developed in the academic world. Still, little effort has been put to measure social impact in waqf organisations. While this paper may be a good start for more researchers to realise the need for SIM, it is only the beginning to many more possible research areas. This paper is done through a critical review of existing literature with no provision of empirical evidences. Thus, considering the idea put forth by Epstein and Yuthas (2014) as a basis, future studies may want to explore how SIM can be designed through a viable impact measurement framework and roadmap by identifying their social and environmental objectives to relevant stakeholders, setting performance metrics and targets related to these objectives, monitoring and managing the performance against the targets set and reporting the performance to relevant stakeholders. Future studies could also include the comprehensive design of SIM framework to include key information from multiple sources including interviews with waqf operators especially to explore their current social impact measurement (if any), identify key impacts and metrics and challenges of adoption of SIM in waqf organisations.

References

Abdul Rahman, A.R., Bakar, M.D., Ismail, Y.: Current practices and administration of waqf in Malaysia: a preliminary study. Retrieved from Malaysia (1999)

Adnan, N.S., Kamaluddin, A., Kasim, N.: Intellectual capital in religious organisations: malaysian zakat institutions perspective. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 16(3), 368–377 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.16.03.11092

Al-Mubarak, T.: The Maqasid of Zakah and Awqaf and their roles in inclusive finance. Islam Civilisational Renewal (ICR) 7(2), 217–230 (2016)

Arshad, R., Zain, N.M., Urus, S.T., Chakir, A.: Modelling maqasid Waqf performance measures in Waqf institutions. Glob. J. Al-Thaqafah (Spec. Issue) 8(1), 157–169 (2018)

Arshad, M.N.M., Haneef, M.A.M.: Third sector socio-economic models: how Waqf fits in? Inst. Econ. 8(2), 72–90 (2016)

Arshad, R., Zain, N.M.: Performance measurement and accountability of Waqf institutions in Malaysia. SHS Web Conf. 36(5), 00005 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/2017360000

Arvidson, M., Lyon, F.: Social impact measurement and non-profit organisations: compliance, resistance, and promotion. Int. J. Voluntary Nonprofit Organ. 25, 869–886 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9373-6

Cameron, W.: Public accountability: effectiveness, equity, ethics. Aust. J. Public Adm. 63(4), 59–67 (2004)

Cunningham, B.K., Ricks, M.: Why measure: nonprofits use metrics to show that they are efficient. But what if donors don’t care? Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. (Summer) 2, 44–51 (2004)

Ebrahim, A.: Accountability in practice: mechanisms for NGOs. World Dev. 31(5), 813–829 (2003)

Ebrahim, A., Rangan, V.K.: The limits of nonprofit impact: a contingency framework for measuring social performance. Harvard Business School General Management Unit Working, Paper No. 10-099. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1611810

Edwards, M., Hulme, D.: Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on non-governmental organizations. World Dev. 24(6), 961–973 (1996)

Emerson, J.: The blended value proposition: integrating social and financial results. Calif. Manag. Rev. 45(4), 35–51 (2003)

Epstein, M.J., Yuthas, K.: Measuring and Improving Social Impacts: A Guide for Nonprofits, Companies, and Impact Investors. Berrett-Koehier Publishers Inc., Oakland (2014)

Frumkin, P.: On being Nonprofit: A Conceptual and Policy Primer. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (2005)

Gonul, O.O., Senyuva, Z.: How social entrepreneurs can create impact for a better world (2020)

Gray, A., Jenkins, B.: Codes of accountability in the new public sector. Acc. Audit. Accountability J. 6(3), 52–67 (1993)

Hall, M., Millo, Y., Barman, E.: Who and what really counts? Stakeholder prioritization and accounting for social value. J. Manage. Stud. 52(7), 907–934 (2015)

Helmig, B., Ingerfurth, S., Pinz, A.: Success and failure of nonprofit organizations: theoretical foundations, empirical evidence, and future research. Voluntas (Manchester, England) 25(6), 1509–1538 (2014)

Husted, B.W., Salazar, J.J.: Taking Friedman seriously: maximizing profits and social performance. J. Manage. Stud. 43(1), 75–91 (2006)

Hyndman, N.S., Jones, R.: Editorial: good governance in charities–some key issues. Public Money Manag. 31(1), 51–155 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2011.573207

Ibrahim, S.H.B.M.: The Need for Islamic Accounting: Perceptions of Its Objectives and Characteristics by Malaysian Accountants. (Ph.D. Thesis), University of Dundee (2000)

Ibrahim, D., Ibrahim, H.: Revitalising of Islamic Trust in Institutions through Corporate Waqf. In: Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Business and Economic Research (2013)

Ibrahim, A.A.M., Khan, S.H.: Waqf management in bangladesh: an analysis from maqasid al-shar‘ah perspective. In: Paper presented at the International Conference on Maqasid Al-Shariah in Public Policy and Governance, Kuala Lumpur (2015)

Ihsan, H., Ayedh, A.: A proposed framework of Islamic governance for waqaf. J. Islamic Econ. Bank. Finan. 11(2), 117–133 (2015)

Ihsan, H., Ibrahim, S.H.M.: Waqf Accounting and management in Indonesian Waqf institutions: the cases of two Waqf foundations. Humanomics 27(4), 252–269 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1108/08288661111181305

Islahi, A.A.: Waqf: A Bibliography. Scientific Publishing Centre, Jeddah (2003)

Kamarubahrina, A.F., Ayedh, A.M.A., Khairi, K.F.: Accountability practices of Waqf institution in selected states in Malaysia: a critical analysis. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Acc. 27(2), 331–352 (2019)

Lee, C., Nowell, B.: A framework for assessing the performance of nonprofit organizations. Am. J. Eval. 36(3), 299–319 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214014545828

Lima, E.P., Costa, S.E.G.: The strategic management of operations system performance. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 10(1), 108–132 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBPM.2008.015924

Lloyd, R., Oatham, J., Hammer, M.: 2007 Global Accountability Report. Retrieved from London: O. W. Trust (2007)

Maas, K., Liket, K.: Social impact measurement: classification of methods. In: Burritt, R., Schaltegger, S., Bennett, M., Pohjola, T., Csutora, M. (eds.) Environmental Management Accounting and Supply Chain Management. ECOE, vol. 27. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1390-1_8

Mahomed, Z.: The Islamic Social Finance and Investment Imperative. Retrieved from Kuala Lumpur: CIAWM (2017)

Mair, J., Marti, I.: Social entrepreneurship research: a source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 41, 36–44 (2006)

Masruki, R., Shafrii, Z.: The development of Waqf accounting in enhancing accountability. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 13(13), 1–16 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.13.1873

Moss, T.W., Short, J.C., Payne, G.T., Lumpkin, G.T.: Dual identities in social ventures: an exploratory study. Entrep. Theory Pract. 35(4), 805–830 (2011)

Moxham, C.: Performance measurement: examining the applicability of the existing body of knowledge to nonprofit organisations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 29(7), 740–763 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570910971405

Mujahid, S.M., Adawiah, E.R.: Islamic social finance and the imperative for social impact measurement. Al-Shajarah J. Islamic Thought Civilisation Int. Islamic Univ. Malay. (Spec. Issue Islamic Bank. Finan.) (2019)

Nicholls, J., Lawlor, E., Neitzert, E., Goodspeed, T.: A Guide to Social Return on Investment. C. O.-O. o. t. T. Sector (2009). Retrieved from United Kingdom. https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/aff3779953c5b88d53_cpm6v3v71.pdf

Nicholls, A.: Capturing the performance of the socially entrepreneurial organisation (SEO): an organisational legitimacy approach. In: Robinson, J., Mair, J., Hockerts, K. (eds.) International Perspectives on Social Entrepreneurship Research, pp. 27–74. Palgrave Macmillan, London (2008)

Nicholls, A.: We do good things, don’t we?: blended value accounting in social entrepreneurship. Acc. Organ. Soc. 34(6–7), 755–769 (2009)

Noordin, N.H., Haron, S.N., Kassim, S.: Developing a comprehensive performance measurement system for Waqf institutions. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 44(7), 921–936 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-09-2015-0257

Ospina, S., Diaz, W., O’Sullivan, J.F.: Negotiating accountability: managerial lessons from identity-based nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Q. 31, 5–31 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764002311001

Oxford (ed.): Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries

Polonsky, M., Grau, S.L.: Assessing the social impact of charitable organizations–four alternative approaches. Int. J. Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Mark. 16(2), 195–211 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.407

Rahman, A.R.A.: Issues in corporate accountability and governance: an Islamic perspective. Am. J. Islamic Soc. Sci. 15(1), 55–69 (1998)

Ramli, N.M., Muhamed, N.A.: Good governance framework for corporate waqf: towards accountability enhancement. In: Paper presented at the World Universities’ Islamic Philanthropy Conference 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (2013)

Ramli, A., Fahmi, F., Darus, F., Rasit, Z.A.: Performance measurement system in the governance of waqf institution: a concept note. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 5(Special), 1026–1034 (2018). https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.spi5.1026.1034

Reynolds, G., Cox, L.C., Fritz, N., Hadley, D., Zadra, J.R.: A Playbook for Designing Social Impact Measurement (2018). Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/a_playbook_for_designing_social_impact_measurement

Sadeq, A.M.: Waqf, perpetual charity and poverty alleviation. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 29(1/2), 135–151 (2002)

Santos, F.: A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 111, 335–351 (2012)

Shaikh, Z.H., Sarea, A.M., Khalid, A.A.: Accounting standards for awaqf: a review. Int. J. Acc. Finan. Rev. 4(2), 37–42 (2019)

Siraj, S.A.: An Empirical Investigation into the Accounting, Accountability and Effectiveness of Waqf Management in the State Islamic Religious Councils (SIRCs) in Malaysia. (Degree of Doctor of Philosophy), Cardiff University (2012)

Snyder, H.: Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Sulaiman, M., Adnan, M.A., Nor, P.N.S.M.M.: Trust me! a case study on the international Islamic university Malaysia’s Waqf fund. Int. Assoc. Islamic Econ. Rev. Islamic Econ. 13(1), 69–88 (2009)

Sulaiman, M., Zakari, M.A.: Efficiency and effectiveness of Waqf institutions in Malaysia: toward financial sustainability. Bloomsbury Qatar Found. J. 1, 43–53 (2015)

Teasdale, S., Alcock, P., Smith, G.: Legislating for the big society? The case of the public services (social value) bill. Public Money Manag. 32(3), 201–208 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2012.676277

Treinta, F.T., et al.: Design and implementation factors for performance measurement in non-profit organizations: a literature review. Front. Psychol. 11, 1799 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01799

Valentinov, V.: The meaning of nonprofit organization: insights from classical institutionalism. J. Econ. Issues 45(4), 901–916 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624450408

Waal, A.D.: Strategic Performance Management: A Managerial and Behavioural Approach. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke (2007)

Westall, A.: Value and the Third Sector: Working Paper on Ideas for Future Research. Retrieved from Birmingham (2009)

Yaacob, H.: Waqf Accounting in Malaysian State Islamic Religious Institutions: The Case of Federal Territory SIRC. (Master’s Degree), International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur (2006)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Zain, N.S., Hassan, R. (2023). What Can Waqf Organisations Learn from Non-profit Organisations on Accountability? A Proposal for Social Impact Measurement. In: Alareeni, B., Hamdan, A. (eds) Innovation of Businesses, and Digitalization during Covid-19 Pandemic. ICBT 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 488. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08090-6_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08090-6_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-08089-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-08090-6

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)