Abstract

Since the 1880s, the Spanish government tried to promote social insurance to achieve political stability. However, a proper welfare state did not develop until the late 1970s. Weak fiscal capacity plus persistent disagreement on who should assume the financial cost of new social programs explain this delay. Before the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), social reform advanced very slowly. Given the lack of fiscal capacity, Spanish policy makers initially promoted contributory social insurance schemes, mostly financed by employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions with little public subsidy. To reduce social conflict, rural laborers were included in these programs along with industrial workers. This, however, generated strong business opposition from both rural landowners and small-sized, labor-intensive businesses (which predominated in Spain). With the advent of democracy in 1931, new social programs were devised, but redistribution demands focused on land reform, an ambitious and controversial policy that eventually led to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. After the war, the Franco dictatorship consolidated a conservative social insurance model. Social benefits were kept very low and funding relied on employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions. The repression of the labor movement alongside trade protectionism allowed companies to easily transfer the cost of social insurance to wages and final prices. The introduction of income tax, after the restoration of democracy in 1977, led to a new social protection model. Tax-funded, noncontributory programs increased and social protection was extended beyond those in stable employment. Unlike in 1931, in 1977, the political consensus necessary to develop social policy was reached. In addition to economic modernization and population aging, decreasing inequality and the example set by the social pacts that spread throughout Europe after World War II must have been crucial in this sense.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

6.1 Introduction

Political instability was a notorious feature of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Spain. It became particularly intense after World War I and peaked in the period 1936–1939 with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Indeed, the country went through two dictatorships—that of Primo de Rivera (1923–1930) and that of Franco (1939–1977)—before the consolidation of democracy in 1977. From the inception of modern social policy, in the late nineteenth century, the explicit objective of the Spanish government was to promote social peace. However, unlike many of its European neighbors, Spain was unable to successfully establish most of the social programs that today we associate with the welfare state (such as old-age and disability pensions, public healthcare, or unemployment insurance). A proper welfare state did not develop until the late 1970s and early 1980s. Even today, when Spain is compared to other European countries, some deficiencies persist. What explains this late development? Why was Spain unable to develop a comprehensive welfare state earlier? Many studies have highlighted the importance of economic and demographic modernization plus the advent of democracy as key factors in the long-term development of the welfare state (Lindert 2004). A number of theories have also emphasized the role of specific actors. According to power resource theories, for example, the demands of the labor movement were crucial (Hicks 1999). However, employers (especially large-sized, capital-intensive companies) also supported social legislation in countries such as the UK or Germany (Mares 2003; Hellwig 2005). Similarly, in Scandinavia, the support of small- and medium-sized farmers was crucial for the development of universal social programs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (Baldwin 1990). This suggests that social policy outcomes are often the result of some sort of cross-class alliance and a mixture of social interests.

Several studies have indicated that it is easier to achieve political consensus for social policy expansion in relatively homogeneous and egalitarian societies, where social affinity (between different social groups) is usually higher and redistribution costs lower (Lindert 2004; Bénabou 2005). These factors seem to have played an important role in Spain. The Spanish government proved unable to raise funds to finance new social programs until the 1977 tax reform. Given this lack of fiscal capacity, Spanish policy makers placed an emphasis on contributory social insurance schemes (which were mostly financed by employers’ and employees’ contributions). However, this generated strong business opposition, especially from rural employers and small-sized businesses, which predominated in Spain. The different political regimes that existed in Spain throughout the twentieth century tried to promote various social protection models. However, the political consensus needed to create (and finance) a comprehensive social protection system was not reached until the late 1970s. The following sections explain the story of this difficult consensus.

6.2 Early Measures and Sources of Social Conflict

In 1883, the Spanish government created the Commission for Social Reform (in Spanish, the CRS: Comisión de Reformas Sociales), which was intended to study the living conditions of the working class and to propose measures to improve them. Two years earlier, in the German Reichstag, Bismarck had advocated for the promotion of social insurance to achieve political support from the working class. Shortly afterward, a comprehensive social insurance scheme was introduced that included sickness insurance (1883), workplace accident compensation (1884), and old-age pensions (1889). In Spain, the years 1881–1883 were marked by intense social unrest affecting both rural and urban centers. Some examples are the strikes in cities such as Barcelona, Valencia, and Madrid, or the events related to La Mano Negra (“The Black Hand”) in Andalusia.Footnote 1 However, unlike the preceding decades, repression was not the government’s only response. After decades of bitter political dispute (including three civil wars in 1833–1839, 1847–1849, and 1872–1876), the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party reached an agreement to alternate peacefully in office during the Bourbon Restoration (1874–1923). This allowed for some political stability, albeit at the price of widespread corruption. To guarantee this alternation in power, before each election, the incumbent party ceded power to an interim government led by the other party, which organized the election and was always able to guarantee its own victory by means of extensive political patronage, vote buying, mass fraud, and even direct coercion (Moreno Luzón 2007).

As part of these attempts to achieve more political stability, the government tried to integrate new emerging social movements (especially, the labor movement) and reduce social unrest in rural areas. Deployment of the police and even the army to deal with social unrest remained a commonplace during the Restoration period. However, in the period 1881–1883 (under the liberal rule of President Sagasta), labor protests became increasingly tolerated by the government. Shortly afterward, in 1887, the Associations Law was passed and union rights were recognized, allowing for the gradual growth of the labor movement (Pérez Ledesma 1990). The first mass demonstration of the Spanish labor movement took place in 1891, with the celebration of May Day. In 1890, the government complemented recognition of social rights with the extension of voting rights to all men. In parallel, publication of the encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891 stimulated the rise of social Catholicism and Conservative Party factions more willing to support social policy. All this contributed to consolidate the reformist trends initiated in 1883.

In the preamble to the Royal Decree creating the CRS, Segismundo Moret (Minister of the Interior at that time) acknowledged that Spanish social policy was underdeveloped compared to other European countries and that “it was not possible to maintain this situation without lessening public peace” (reproduced in Castillo 1985, p. CXLIII). The explicit objective of the CRS was to achieve “[social] peace (…) between the two large production factors: labor and capital” (p. CXLIV) and channel labor demands away from revolutionary measures. The government, however, focused not only on the new conflicts emerging in industrial cities but also on the traditional conflicts of rural areas. Nineteenth-century Spanish agriculture was characterized by high land inequality. In southern Spain, large estates (or latifundios) represented more than half of the total rural area, and peasant uprisings had been common since the early nineteenth century (Malefakis 1970). After the visit of Bakunin’s envoy, Giuseppe Fanelli, to Spain in 1868, rural Andalusia became a breeding ground for anarchist militants. In fact, anarchist unions predominated among Spanish labor unions until at least the 1920s, and landless laborers always represented a large share of total union membership.Footnote 2 Since the government’s objective was to deactivate revolutionary social movements, paying attention to rural areas was crucial. Spanish social reformers, however, never tried to implement any type of land reform to change the structure of land ownership. Rather, they hoped to find a way to “alleviate the evils affecting the rural working classes,” so that “property can exist safely” (Castillo 1985, p. CXLV).

The CRS was initially charged with a number of social tasks: to promote the regulation of child and female labor, and of working conditions in general in industrial factories; to stimulate the creation of Jurados Mixtos (to resolve industrial disputes between employers and employees); and to encourage the creation of old-age and disability pension funds, as well as agricultural banks and reforms facilitating rural laborers’ access to land (p. CXLIX). However, the only significant work undertaken by the Commission before 1890 was an ambitious study on the conditions of the working class that compiled a great deal of information but did not result in any specific policy measures. In fact, both socialist and anarchist unions viewed the CRS with skepticism and were convinced that it would not succeed in improving workers’ living conditions (De la Calle 2004). In 1890, the CRS was reformed and became a sort of advisory body for the government; but again no specific measures were introduced until 1900, when the occupational accidents law was passed. This law obliged industrial employers to pay mandated benefits to their employees in case of work-related accidents. However, the initial impact of this measure was very limited. The benefits established by the government were low and employers often failed to fulfill their commitments due to lack of inspection (Silvestre and Pons 2010). This anticipated two permanent features of social policy in Spain: employers’ opposition to social reform and the inability (unwillingness perhaps) of the government to enforce social legislation.

6.3 From Voluntary, State-Subsidized Insurance to Compulsory Insurance

In 1903, the former CRS was replaced by the Institute of Social Reform (in Spanish, the IRS: Instituto de Reformas Sociales). Again, its objectives were to promote social legislation and oversee its enforcement. To achieve social legitimacy, the IRS was expected to include representatives from employees and employers alike in its decision-making bodies. Employer representation, however, was very limited, partly because employers showed little interest in participating, and partly because of a long-standing tradition of individualism among Spanish business groups. Labor representation was also very limited. The anarchist union, the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo), rejected any kind of collaboration with the government (as had already happened with the CRS), being convinced that the IRS was useless and a distraction from the (revolutionary) interests of the working class. In turn, the board of directors of the IRS did not consider the social Catholic unions to be genuine representatives of labor interests because they brought together within a single organization both employers and employees. As a result, labor representation relied almost exclusively on the socialist union, the UGT (Unión General de Trabajadores), which this time proved more willing to collaborate in the government’s reformist agenda (Montero 1988).

The IRS was unable to promote the permanent social pacts between labor and capital sought by the government, but it played a very active role in promoting social legislation. One of the projects emerging from the IRS was the National Institute of Social Security (in Spanish, the INP: Instituto Nacional de Previsión), created in 1908 to manage what was known as the Retiro Obrero, or worker’s retirement fund. This was a voluntary, State-subsidized old-age pension scheme. Potential beneficiaries were all wage earners (from industry and agriculture alike) with an annual income of less than 3000 pesetas, which was a high threshold at that time.Footnote 3 When designing the Retiro Obrero, the government followed the example of the voluntary insurance schemes, with little public subsidies, established in France, Belgium, and Italy, instead of the compulsory insurance model prevailing in Germany (Montero 1988; Murray 2003, 2007). This is in part explained for ideological reasons. Spanish social reformers believed that voluntary insurance had the advantage of ensuring that workers would be actively involved in obtaining a solution to their problems because in order to obtain the governmental subsidy, workers had to voluntarily join an insurance fund (and pay the corresponding fees). In contrast, compulsory insurance, it was said, would not promote individual virtues, as “its automatic retentions on the pay-roll (…) do not compel the insured person to adopt a pro-saving attitude” (Eza 1914, p. 43).

However, voluntary insurance schemes were also preferred for practical reasons, since they entailed a much lower cost for the government. Compulsory insurance was considered an “overwhelming and monstrous bureaucratic mechanism,” whereas voluntary State-subsidized insurance programs provided an effective means to “alleviate government burdens,” as administration was left to private funds (González and Oyuelos 1914; pp. 230 and 267). Some social reformers even argued that social insurance would help reduce public spending on traditional poor relief: “The State budget cannot meet all social needs (…). The more the government promotes and channels social insurance, the less it will have to attend in the future to expenditure on poor relief, which is overwhelming for the public treasury” (Maluquer 1926, p. 220). As in Germany, more than fighting poverty, the Spanish government’s objective was to integrate the labor movement politically. But unlike Germany, Spain tried to avoid compulsory insurance for as long as possible. The Spanish government was reluctant to assume any increasing cost to improve social protection, and refused to significantly alter the tax structure. As one might expect, the Retiro Obrero had a very limited impact in this context. In 1918, after 10 years in force, only around 1% of the active population was covered (Elu 2010).

Before World War I, the labor movement was too weak to influence government policies. There were some outbreaks of violence and mass demonstrations before 1913, such as the 1909 Semana Trágica, which plunged Barcelona into violent anticlerical riots, and the 1903–1904 wave of rural strikes. However, even in 1910, union membership only accounted for around 1% of the active population (Silvestre 2003). This changed quite suddenly during World War I. The economic disturbance caused by the war and the contagious effect of the Russian Revolution led to a huge increase in social unrest. Largo Caballero (a socialist representative in the Spanish parliament) attributed the “entire labor mobilization occurring from 1916 to the general strike in August [1917]” to “the high cost of living and the lack of work” (cited in Espuelas 2013a, p.87). Union density increased substantially in this context, reaching 12% of the active population in 1920. To regain political stability, the government tried to stimulate the development of social legislation. In 1917, in a Conference for Social Insurance, the government made a commitment to create a comprehensive social insurance system (covering workplace accidents, old age, illness, maternity leave, and unemployment). This time, the government recognized that, to be effective, social insurance had to be compulsory.

After the conference, the Socialist Party (which had won its first seat in parliament in 1910) demanded that the government honor its social promises. Several projects, including the creation of new unemployment and health insurance schemes and the extension of workplace accident insurance to agriculture, were discussed in parliament and within the INP. As shown by Domenech (2011), the greater executive powers of governments after 1917 in response to political crises allowed for a faster pace of reform. However, as for social insurance, the only program that came to fruition was the 1919 Retiro Obrero Obligatorio or Compulsory Worker’s Retirement fund. As before World War I, the government remained reluctant to assume the financial cost of new social programs. Public deficits were constant during the early decades of the twentieth century, and the government proved unable to collect sufficient taxes to maintain a balanced public budget (Comín 1996). The creation of tax-funded programs, such as the 1891 Danish old-age pensions, was never contemplated in this context. And when the Compulsory Worker’s Retirement scheme was established in 1919, workers were not required to make compulsory contributions. The government was trying to forestall labor opposition to its new social reforms, in a context of intense social unrest. However, this meant that employers would assume the bulk of the cost of social insurance.

In fact, business opposition to social insurance in Spain was fierce, especially among small-sized labor-intensive companies, as seems to have been the case in other European countries as well. Resistance to compulsory social insurance was often more severe among small-sized companies and rural landowners than among large-sized, capital-intensive companies, which in some cases even supported the introduction of social insurance as a means to enhance productivity growth, reduce labor unrest, or gain competitiveness over smaller rivals. Often, large firms had social insurance policies for their employees before mandated benefits were established (Murray 2007; Mares 2003; Hellwig 2005). In Spain, however, small-sized companies predominated (Comín and Martín Aceña 1996). Unlike Bismarck’s Germany, Spain lacked a broad industrial base willing to support compulsory social insurance. Moreover, unlike many European countries, in which the rural population was often excluded from social insurance, the new Compulsory Worker’s Retirement scheme covered both rural and urban workers. As mentioned before, revolutionary movements wielded great influence in rural Spain, especially in areas where large farms predominated. Since the government’s objective was to reduce social unrest and channel labor demands through nonrevolutionary measures, extending social insurance to agriculture was crucial. However, this became an additional obstacle to social reform. When the Compulsory Worker’s Retirement scheme came into effect, affiliation records in agriculture were very low (Elu 2010), and the combined opposition of rural landowners and small-sized companies frustrated plans to extend workplace accident insurance to agriculture and to create a new unemployment insurance scheme after World War I (Del Rey 1992; Espuelas 2013a).

The labor movement did not show full support for social reform either. Socialist sectors supported the government’s social plans and indeed asked for more State intervention; however, revolutionary sectors, basically the anarchist movement, did not trust the government’s intentions and viewed social insurance plans as a distraction from the true interests of the working class. The government’s inability to fulfill its social promises and the slow pace of social policy development in Spain reinforced the revolutionary position and hindered political integration of the labor movement within the Restoration regime (Barrio 1997). Neither did the political changes of the early 1920s have a positive effect. Until then, the government had proved unable to make good many of its social promises. However, after the military coup of 1923 and the establishment of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1923–1930), post-World War I reform attempts were abandoned. The government only introduced some subsidies for large families in 1927, a policy consistent with the heightened influence acquired by the Catholic Church during the dictatorship (Velarde 1990). To regain momentum, social policy had to wait until the arrival of democracy in 1931.

6.4 The Second Republic: Momentum and Limitations

The advent of the Second Republic (1931–1936) marked the beginning of the first truly democratic period in Spanish history. This short period of time generated high hopes for reform among diverse social sectors that aspired to democratize Spanish political and social life. These expectations, however, soon turned into acute social tension, with the highest levels of political mobilization and social unrest in Spanish contemporary history (Pérez Ledesma 1990). During the Second Republic, the Socialist Party became the most voted party, although it never obtained sufficient votes to rule on its own: from 1931 to 1933, it was in office in coalition with other left and center-left parties, while in the second legislature, from 1933 to 1935, it was the main party in opposition, after right and center-right parties reached an agreement to form a government. The growth of the Socialist Party in this new democratic context was due not only to the broadening of its urban and industrial base but also to the rapid consolidation of a broad rural base. By 1932, the socialist union, the UGT, had 1,041,539 members, of whom 445,414 were rural laborers (Tuñón de Lara 1972, p. 857–858).

As in the preceding decades, rural interests conditioned the progress of social policy during the Second Republic. The implicit alliance between landless laborers and industrial workers gave the Socialist Party sufficient political power to launch its program of social reform, and several social rights were included in the 1931 Spanish Constitution. The right to social insurance, for example, was granted in Article 46: “The Republic guarantees to all workers the necessary conditions for a dignified existence. Its legislation will regulate the cases of sickness, accident, unemployment, old-age, disability, and survivor’s insurance.” Progress in social legislation was particularly striking from 1931 to 1932, when the Socialist Party was in office (Samaniego 1988). The government introduced maternity insurance (granting healthcare during childbirth and maternity leave for working women); created a voluntary, State-subsidized unemployment insurance scheme; and extended workplace accident compensation to agriculture. Moreover, a plan was devised to unify all existing social insurance programs plus new programs (providing healthcare, sickness leave, and disability and survivor’s pensions) within a single social security system. However, discussion of the details of this plan dragged on for years, and the military coup of 1936 eventually prevented it from being passed (Samaniego 1988).

The obstacles faced by this unification plan were diverse. Mutual aid associations and commercial insurance companies providing sickness-related benefits opposed government plans because they feared being displaced by State insurance and instead advocated for voluntary programs. Doctors feared the loss of professional freedom that State insurance might entail. They believed that such a program would reduce “the medical classes to the role of simple civil servants, controlled by other administrative civil servants” (cited in Samaniego (1988), p. 368). The government also had to deal with the customary opposition from employers, and to a lesser extent with opposition from workers. In regions and provinces such as Catalonia, Zaragoza, Galicia, and Valencia, strikes were held, often promoted by the anarchist union, the CNT, in protest against the 1931 compulsory maternity insurance scheme. Working women rejected the corresponding mandatory contributions (Pons 2010). The government was aware of this potential opposition, but as the INP put it in a 1936 pamphlet, it hoped that workers’ opposition to compulsory contributions would decrease “if the insured person receives instant benefits, such as those granted by health insurance” (INP 1936, p. 39).

A crucial characteristic of the new plan was that it “does not cast on the State any burden that has not already been recognized” (INP 1936, p. 74). This meant that the government would maintain public subsidies for preexisting old-age pension and maternity funds, but the new benefits devised in the unification plan (healthcare, sickness leave, and disability and survivor’s pensions) would be entirely financed by employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions. The government announced this as a virtue: taxpayers did not need to worry about any unbearable burden. But it was precisely this aspect that probably aggravated opposition from employers and employees. Above all, this reflects the Spanish government’s persistent unwillingness to assume the cost of new social programs, which was in part the result of weak fiscal capacity. As mentioned before, public deficit was a constant feature of the early decades of the twentieth century, a situation that was exacerbated by World War I and the Great Depression. Left-wing governments in the Second Republic implemented several tax reforms to increase public revenues, raising tax rates on land ownership and industrial equity and introducing a new tax on gasoline. The most important measure was the creation of an income tax in 1932, but even this was a timid reform, unable to solve the government’s financial problems.

Only people with annual incomes above 100,000 pesetas were subject to the new income tax, and tax rates ranged between a minimum of 1% and a maximum of 11% for incomes above 1,000,000 pesetas. The 1932 Spanish GDP was 1448 pesetas per person,Footnote 4 so the percentage of population subject to the new income tax was very low. Jaume Carner, Minister of Finance at the time, was convinced that this was the only feasible reform, believing that a more ambitious project would have met with insurmountable opposition. He hoped that in the future, the new tax could be gradually extended to a broader segment of the population by lowering the 100,000 peseta threshold (Costa 2000). After these reforms, State revenues increased, but the public deficit remained (Comín 1996).

However, the most ambitious social reform undertaken during the Republican period was the agrarian reform, most actively promoted by the Socialist Party, which had a broad rural base. In launching this reform, the socialists were supported by Manuel Azaña and left-wing republicans, who believed that meeting the socialists’ demands was the only way to guarantee that the working classes “would remain loyal to the Republic rather than succumb to Anarcho-syndicalist cries for total opposition” (Malefakis 1970, p. 192). The explicit objective of the agrarian reform was to achieve social peace in rural areas and contribute to economic and political democratization. However, the Spanish government was unable to overcome the predictable opposition from rural landowners and enlist the support of small- and medium-sized farmers. During the first legislature (under the republican-socialist coalition government), the reform advanced very slowly, while during the second (with a right-wing coalition in government), it was practically paralyzed. This first disappointed and then radicalized the Socialist Party’s rural base. When the left returned to power in February 1936, the agrarian reform once again made headway, but was halted by the military coup of July 1936. A diversity of factors lay behind the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, but tensions resulting from the agrarian reform played a crucial role (Simpson and Carmona 2020).

6.5 The Franco Dictatorship: A Conservative Social Insurance Model

The outcome of the Spanish Civil War (1931–1936) was the imposition of the Franco dictatorship (1939–1977). Unlike what had happened after previous civil conflicts, such as the Carlist Wars in the nineteenth century, this time there were no attempts at reconciliation. On the contrary, the goal was to inflict a definitive defeat on the enemy to avoid a re-emergence of the reformist ambitions of the Second Republic (Tusell 2005). The army led postwar repression and the country remained under military law until April 1948. Political parties were outlawed, with the exception of the Falange Española, the official party. In the domain of labor relations, employers and employees were forced to join the so-called vertical union. Independent labor unions were prohibited, as were strikes, which were considered sedition and therefore an offense punishable by death penalty (Pérez Ledesma 1990). Business associations, by contrast, remained legal and could even act as pressure groups (Molinero and Ysas 1998). Many businessmen and landowners became members of parliament, forming part of the dictatorship’s political elite together with high-ranking civil servants, the military, the Catholic Church, and politicians from monarchic groups and the Falange (Jerez 1996).

The Spanish economy recovered very slowly after the Civil War. Pre-war income levels were not restored until 1952. Real wages performed even worse: industrial real wages did not recover pre-war levels until 1962–1963. In agriculture, real wages in 1959 represented only 77% of the real wage in 1936. This poor performance was mostly the result of curtailing workers’ rights (Vilar 2004). As for social protection, most of the social insurance schemes created before the Civil War continued, the only exception being unemployment insurance, which was abolished and not reintroduced until 1961. The dictatorship’s policy makers believed that unemployment benefits only contributed to laziness: Girón de Velasco, Ministry of Labor between 1941 and 1957, claimed that “unemployment insurance [in Europe] fatally engendered a tendency to indolence and indirectly contributed to vice and even degeneration” (1951, p.19). The Republican project for social insurance unification was also abandoned. The Franco dictatorship, however, did launch some new social programs. During the Civil War, the government created the Auxilio de Invierno (Winter Relief), an institution linked to the Falange, that shortly afterward was renamed the Auxilio Social (Social Relief). Its initial mission was to meet the social needs derived from the war on the side of pro-Franco rebels. Later on, as Franco’s army advanced through Republican areas, the Auxilio Social became an instrument of propaganda, distributing bread to the population and organizing soup kitchens. Once the war was over, the Auxilio Social became a parallel welfare institution to traditional poor relief (Cenarro 2006).

Also during the war, a family allowance called the Subsidio Familiar was introduced, which provided bonus payments to all wage earners based on number of children. Pro-family (conservative) policies played a key role in the rhetoric of the dictatorship, and this allowance was largely an outcome of the regime’s population ideology and the influence of the Catholic Church’s social doctrine, which advocated for a sufficient family wage (Velarde 1990). The measure was also aimed at reducing female labor participation. Women’s work was attributed with all kinds of social evils:

mothers are forced to work outside the home because of a lack of resources (…) and the consequences are fatal. Increased maternal mortality during childbirth; increased infant mortality (…); a brutal drop in birth rates (…); no education for the children, [who are] abandoned to the evil teachings of the street; her housework skimped, making the home unpleasant and pushing her husband to the tavern and bar (…) Returning mothers to the home is the ideal and we need to move toward it. The Subsidio Familiar is the most effective way. (Aznar 1943, pp.16–17)

Lastly, a compulsory health insurance scheme (in Spanish, SOE: Seguro Obligatorio de Enfermedad) was also set up from 1942 to 1944. According to Girón de Velasco, the goal of this program was to improve health and increase workers’ performance, in line with the virtues that nineteenth-century social reformers attributed to social insurance.Footnote 5 Girón de Velasco, moreover, attributed an explicitly political function to the new sickness insurance: “proselytism, [to] gain new adepts for the motherland and the revolution” (1943, p. 67). However, despite propaganda, social protection levels remained very low under the Franco dictatorship. In 1958, Spanish social spending was only 3.3% of the GDP, whereas in Italy or Greece, it was above 10% (Table 6.1). Coverage rates remained very low too. Rural workers were largely excluded from social protection before 1959,Footnote 6 but even in 1959, health insurance only covered 37% of the active population, and the total number of beneficiaries (including the insured person’s family) only accounted for 38% of the total population. As for old-age pensions, coverage rates were even lower. In 1959, only 32% of the active population was included in the scheme.Footnote 7

Pension benefits also remained very low in the 1940s and 1950s, as these were only partially indexed to inflation (in a context of high inflation rates). Table 6.2 shows the evolution of old-age pension benefits from 1940 to 1959. As is shown in column 1, average benefits in nominal terms increased gradually. However, when we analyze the evolution in real terms, the result is completely different (column 3). Average real pension benefits decreased constantly between 1940 and 1955. They recovered after 1956, but even in 1959, real benefits were similar to those of 1940. If replacement rates are analyzed, the results are similar. Taking as a reference the average unskilled industrial wage, average replacement rates oscillated between 20 and 30% over the entire time-period (column 5). This means that social protection remained limited to a minimum during the Franco dictatorship. Moreover, this meager social protection network was almost exclusively financed by employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions. In 1959, government subsidies to social insurance funds (including old-age pensions, health insurance, and the Subsidio Familiar) accounted for 12% of total revenues (INP 1960). This allowed the Franco regime to finance (ungenerous) social insurance without increasing taxation.

Business groups showed little opposition to this social insurance model (at least until the 1960s). During the 1940s and 1950s, the Franco dictatorship adopted an aggressive import substitution policy, alongside very active State economic intervention. Wages and prices were subject to government regulation and labor unions were prohibited, which allowed employers to easily transfer the cost of social insurance to wages (as potential workers’ opposition was silenced). In parallel, trade protectionism allowed employers to transfer part of the cost of social insurance to final prices and consumers (Espuelas 2012). This situation, however, changed gradually after 1959. To overcome the 1957–1959 crisis, the government devised the 1959 Stabilization Plan. The peseta was devalued to gain international competitiveness, and a strict monetary policy was implemented to defend the new exchange rate. In parallel, a number of liberalizing measures were gradually introduced, and the most aggressive forms of State intervention were abandoned. State control over private investment diminished, and the economy was increasingly opened up to international trade. After an initial recession in 1959–1960, the Spanish economy recovered very rapidly, growing at an average annual rate of 7% between 1960 and 1974.Footnote 8

Economic growth stimulated social policy expansion. Urbanization and population aging generated new social demands, while rising incomes generated higher public revenues (Lindert 2004). Rural-urban migration helped to overcome rural landowners’ traditional opposition to social insurance, as these became more willing to accept social insurance in order to retain the population in rural areas. In 1959, the government created the National Mutual Fund for Agrarian Social Security to “place the protection granted to agricultural workers on the same level as that for urban workers” (Decree 613/1959). The gradual growth of a clandestine labor movement also favored social policy expansion from the mid-1960s onward. Between 1956 and 1958, there were a number of strikes demanding higher wages, which started in Pamplona and extended to the Basque Country, Barcelona, and mining areas in Asturias. For the first time since the Civil War, the government’s response consisted of a combination of repression and (some) social concessions (Pérez Ledesma 1990). In the context of the aforementioned economic liberalization, the 1958 Collective Agreement Act was passed, allowing employees to negotiate wages and working conditions with employers.

Strikes remained illegal, especially when involving political demands, but they were tolerated when held for economic reasons (i.e., when they were linked to the collective bargaining process legalized in 1958). The number of collective agreements increased rapidly thereafter. In 1962, the number of employees included in a collective agreement was above 2,300,000, while in 1969 it exceeded 3,700,000 (Maluquer and Llonch 2005). This allowed employees to obtain higher wages in exchange for increased productivity, which in turn stimulated economic growth. However, this measure also had unintended consequences for the government. It favored the rise of a new clandestine labor movement, which took advantage of the new organizational opportunities offered by the 1958 collective bargaining law to include political and social demands in labor mobilizations (Pérez Ledesma 1990; Molinero and Ysas 1998). In parallel, new opposition movements supporting workers’ demands appeared in the mid-1960s and early 1970s, led by university students and social Catholic groups. In combination, these changes became the main source of political instability in the final years of the Franco dictatorship (Tusell 2005).

Once again, the government’s response consisted of a combination of severe political repression and social policy expansion. A new Social Security Act came into effect in 1963/1967, bringing together preexisting social insurance programs under a single and more streamlined social security system. Coverage that had previously been limited to medium- and low-income workers was now extended to all wage earners. This represented some progress toward universal cover, albeit the population without stable ties to the labor market remained marginalized. Social spending grew very rapidly after the 1963/1967 reforms, rising from 4.06% of the GDP in 1966 to 11.7% in 1975 (see Table 6.1). However, the cost of social security remained borne almost exclusively by employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions (with very little public subsidy during the entirety of the dictatorship). Growing labor demands and increasing exposure to international trade prevented employers from transferring the cost of social security to wages or final prices as easily as before. As a result, employers’ complaints about the unbearable cost of social insurance became recurrent in the 1970s (Cabrera and Del Rey 2002). Moreover, even in 1975, Spanish social spending was only 59% of the European average (Table 6.1). For Spain to catch up with its European neighbors, it would be necessary to wait until the restoration of democracy in 1977.

6.6 Democracy and Convergence with Europe

After Franco’s death in 1975, political change accelerated. The transition to democracy, however, coincided with a period of economic downturn and increasing unemployment. In this context, social policy proved crucial for political stability and democratic consolidation. The best example of the social consensus reached during the transition to democracy is the 1977 Moncloa Pacts. Workers’ and employers’ representatives plus the main political parties agreed to accept wage moderation and macroeconomic stabilization policies to curb inflation, in return for greater social protection, progressive taxation, and the consolidation of political freedoms. One very important outcome of the Moncloa Pacts was the 1977 tax reform and the introduction of income tax in 1978 (Torregrosa-Hetland 2018). This overcame one of the most important historical barriers to the development of Spanish social policy: the lack of fiscal capacity. Public subsidies to social security institutions increased, and the funding of social insurance no longer relied on employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions as it had under the Franco dictatorship. In the 1980s, Spanish social spending reached similar levels to that of other southern European countries such as Italy or Greece, although it remained below that of the leading countries, such as Sweden or Germany (Table 6.1). Access to healthcare became universal in 1986, welfare benefits for disabled persons improved substantially after 1982, noncontributory old-age and disability pensions were introduced in 1990, and the regional governments gradually introduced minimum income programs for low-income families throughout the 1990s. All this represented a gradual improvement in social provision, and permitted the expansion of cover to sectors without stable ties to the labor market.

Unlike in 1931, with the arrival of democracy in 1977, the political consensus necessary to develop social policy was reached. There are at least two reasons that seem crucial in this respect. The first one has to do with the evolution of inequality. In 1977, overall inequality was significantly lower than in 1931 (Prados de la Escosura 2008). In egalitarian countries, social affinity between middle- and lower-income groups tends to be higher and the costs associated with redistribution smaller, resulting in more political support for social policy expansion (Lindert 2004; Bénabou 2005; Espuelas 2015). The nature of Spanish inequality in 1977 and in 1931 was also substantially different. Until the 1950s, inequality was mostly driven by the gap between property and labor incomes, and particularly by land inequality, which was the main asset of the economy. This helps explain both the insistence on agrarian reform by the progressive governments of the Second Republic and the subsequent political instability. Since land is an immobile asset (with no exit options), when there are threats of expropriation, landowners might be interested in supporting nondemocratic governments to avoid redistribution (Boix 2003). In 1977, instead, wage dispersion had become the main component of inequality. With industrialization, land rents gradually lost relevance in the economy, and inequality became much less dependent on land inequality. This would explain why tax-and-transfer redistribution replaced expropriation demands.

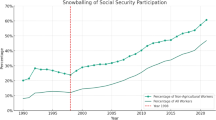

The international context must also have played a crucial role. In the Second Republic, redistributive struggles around land reform were mixed with the rise of fascism and left-wing revolutionary movements in interwar Europe. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War was in part a precedent for the political violence that assailed the continent during World War II. By contrast, in 1977, Spain had as a reference the social pacts that spread throughout Europe after World War II and that served as a basis for the growth of the welfare state and for preserving political stability. The Moncloa Pacts were the Spanish equivalent of these social pacts. Actually, both the center-right UCD (the Union de Centro Democrático) and the Socialist Party stimulated social spending growth when they were in office in the late 1970s and early 1980s. However, the Keynesian consensus established after World War II gradually broke down in the 1980s, leading to social spending stagnation in many European countries. In Spain, social spending also stagnated in this time period, but at a lower level (Fig. 6.1).

Public social spending in Europe (% of GDP), 1950–2005. (Source: See Table 6.1)

From 1985 onward, and especially after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, public deficit and inflation control became the main targets of economic policy. As a result, the Spanish government introduced a number of measures to limit social spending (under the rule of both the socialist and the center-right Popular Party). Just as with the 1977 Moncloa Pacts, when both center-right and center-left political parties accepted the Keynesian consensus, in the 1980s and 1990s, both the center-right and the center-left adopted what Offer and Söderberg (2016) call the market turn. Guillén and Álvarez (2004) qualify this and say that the Socialist Party accepted the European Union’s prescriptions for limiting public spending, whereas the Popular Party actually encouraged these policies. In any event, it is in this context that the Toledo Pact was signed in 1995 with the support of almost all political representatives at the time. Its purpose was to guarantee the financial stability of the pension system by establishing a clear distinction in the funding sources for contributory and noncontributory pensions. Contributory pensions became linked to the availability of funds from employers’ and employees’ contributions, which allowed for a reduction in government subsidies to social security funds. Noncontributory pensions, in turn, became exclusively financed by government subsidies.Footnote 9

However, one of the main limitations of today’s social protection in Spain is that the generosity of noncontributory benefits lags far behind that of contributory benefits. This has led to a kind of dualism in the sense that social protection is significantly better for labor market insiders (with long contribution records and access to contributory benefits). This in turn involves a gender bias, since women have historically had lower activity rates (especially under the Franco dictatorship) and therefore shorter contribution records (León 2002). On the other hand, Spanish public spending on family support remains below that of most European countries (Table 6.3). Parental leave provisions are shorter and family cash benefits and social services for child care are lower. This has limited female labor participation and widened the gender income gap (León and Salido 2016). To some extent, the precariousness of family policy in democratic Spain is a reaction to the central role assigned to (antifeminist) family policy in the propaganda of the dictatorship. The first democratic policy makers omitted references to family policy to avoid being identified with the authoritarian past (Valiente 1996). Later, the restrictions on social spending growth in the mid-1980s and early 1990s hampered the development of alternative (more pro-feminist) family policies. The current gap in aggregate social spending between Spain and Europe is to a large extent the result of this gap in public support to young families and new parents.

6.7 Conclusions

Since 1880s, the Spanish government tried to promote social insurance to achieve political stability, integrate the labor movement politically, and reduce social unrest in rural areas. However, unlike many of its European neighbors, Spain was unable to successfully establish most of the social programs that today we associate with the welfare state. Weak fiscal capacity plus persistent disagreement on who should assume the financial cost of new social programs explain this delay. Before the Spanish Civil War, social reform advanced very slowly. Initially, Spanish social reformers promoted voluntary State-subsidized insurance schemes. The Spanish government was reluctant to assume any increasing cost to improve social protection, and (as one might expect) these measures had a very limited impact in this context. After World War I, in a context of intense social unrest, the government advocated for the creation of compulsory social insurance programs. Several projects were discussed. However, the only program that came to fruition was the 1919 compulsory old-age pension scheme. To forestall labor opposition, workers were not required to make compulsory contributions, and to deactivate revolutionary social movements in agriculture, coverage was extended to rural workers. However, this generated strong business opposition, especially from rural employers and small-sized businesses, which predominated in Spain.

With the advent of democracy in 1931, new social insurance programs were introduced, but traditional obstacles persisted. Weak fiscal capacity, plus the opposition from employers, some sectors of the labor movement, and specific interest groups (such as insurance companies or doctors), frustrated government plans to create a comprehensive social security system. However, redistribution demands during this period focused on land reform, an ambitious and controversial policy that eventually led to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. After the war, the Franco dictatorship consolidated a conservative social insurance model. Social benefits and coverage rates were kept very low. Even in 1958, Spanish social spending was only 3.3% of GDP, whereas in Italy or Greece, it was above 10%. Moreover, funding relied on employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions, which allowed the government to finance (ungenerous) social insurance without increasing general taxation. Business groups showed little opposition to this model. The repression of the labor movement alongside trade protectionism allowed companies to easily transfer the cost of social insurance to wages and final prices.

This situation, however, changed gradually from the 1960s onward. The economy gradually opened up to international trade, economic growth accelerated, and a clandestine labor movement emerged. A new Social Security Act came into effect in 1963/1967, and social spending grew very rapidly thereafter, in part as a result of increasing political instability. Social security remained financed almost exclusively by employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions. However, growing labor demands and increasing exposure to international trade prevented employers from transferring the cost of social security to wages or final prices as easily as before. The restoration of democracy in 1977 and the subsequent tax reform led to a new social protection model. Public subsidies to social security institutions increased, and the funding of social insurance no longer relied almost exclusively on employers’ and employees’ compulsory contributions as it had under the Franco dictatorship. In the 1980s, Spanish social spending reached similar levels to that of other southern European countries such as Italy or Greece, although it remained below that of the leading countries, such as Sweden or Germany.

Unlike in 1931, the arrival of democracy in 1977 did lead to the political consensus necessary to increase taxation and develop social policy. Rapid economic growth, urbanization, and population aging played a role in this sense, but two additional factors must also have been crucial. Firstly, in 1977, inequality was lower and much less dependent on land inequality than in 1931. This would explain why less controversial tax-and-transfer redistribution replaced 1930s’ expropriation demands. Secondly, the international context was also very different. Instead of the political extremism that shook interwar Europe, 1977 Spain had as a reference the Keynesian consensus. Somehow, the 1977 Moncloa Pacts were the Spanish equivalent of the social pacts that spread throughout Europe after World War II.

Notes

- 1.

Allegedly, La Mano Negra was a secret anarchist organization to which the government attributed a number of violent actions, including the destruction of crops and even murders. According to Tuñón de Lara (1972), however, as a formal organization, La Mano Negra never existed. Rather, the Spanish government leveraged political violence in rural Andalusia as an excuse to initiate severe repression and quell peasant revolts.

- 2.

In 1882, 20,915 of the 57,934 members of the Spanish Anarchist Federation were agricultural workers, mostly from Andalusia, and total Andalusian membership (38,349) still far exceeded that of industrial Catalonia (13,201) (Malefakis 1970, p. 159). In 1919, the anarchist union CNT (Conferederación Nacional del Trabajo) had 700,944 members, while the socialist union UGT (Unión General de Trabajadores) had 150,382 members (Silvestre 2003, appendix). The initial growth of the UGT was slower than that of the anarchist unions, and more restricted to industrial and urban areas such as Madrid and the Basque Country. When the UGT eventually surpassed the number of affiliates of the CNT in the 1930s, it was possible due to a large increase in its rural affiliates.

- 3.

In 1910, the average daily wage in industry was 2.88 pesetas. Assuming 280 working days per year, this would indicate an annual wage of 806.40 pesetas (see Vilar (2004), p. 156).

- 4.

Prados de la Escosura (2003), p. 521

- 5.

- 6.

Rural laborers were excluded from old-age pensions before 1943. Permanent rural laborers were excluded from health insurance until 1953, and nonpermanent rural laborers until 1958.

- 7.

- 8.

GDP figures from Prados de la Escosura (2003)

- 9.

To qualify for contributory pensions in the Spanish system, a previous contribution record is required, whereas for noncontributory pensions, it is not. Before the Toledo Pact, social insurance funds (receiving compulsory contributions plus government subsidies) could be used to finance either contributory or noncontributory benefits. For more details, see Comín (2010).

References

Aznar S (1943) Fundamentos y motivos del seguro de subsidios familiares. Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de Madrid, enero-junio

Baldwin P (1990) The politics of Social Solidarity and the Bourgeois Basis of the European Welfare State, 1875–1975. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Barrio A (1997) El sueño de la democracia industrial en España. In: Suárez M (ed) La Restauración: entre el liberalismo y la democracia. Alianza, Madrid, pp 1917–1923

Bénabou R (2005) Inequality, technology and the social contract. In: Agion P, Durlauf SN (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1596–1638

Boix C (2003) Democracy and redistribution. Cambridge University Press, New York

Cabrera M, Del Rey F (2002) El poder de los empresarios: Política e intereses económicos en la España contemporánea, 1875–2000. Taurus, Madrid

Castillo S (ed) (1985) Reformas sociales, Información oral y escrita publicada de 1889 a, vol 1893. Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Madrid

Cenarro A (2006) La sonrisa de Falange: auxilio social en la guerra. Crítica, Barcelona

Comín F (1996) Historia de hacienda pública II. España 1808–1995. Crítica, Barcelona

Comín F (2010) Los seguros sociales y el Estado del Bienestar en el siglo XX. In: Pons J, Silvestre J (eds) Los orígenes del Estado del Bienestar en España, 1900–1945: los seguros de accidentes de trabajo, vejez, desempleo y enfermedad. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza

Comín F, Martín Aceña P (1996) Rasgos históricos de las empresas en España: un panorama. Revista de Economía Aplicada 12(5):75–123

Costa MT (2000) Biografía del ministro de hacienda Jaume Carner. In: Comín F (ed) La Hacienda desde sus ministros. Del 98 a la guerra civil. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza

De la Calle D (2004) La Comisión de Reformas Sociales: la primera consulta social al país. In: Palacio Morena JI (coord) La Reforma Social en España. En el centenario del Instituto de Reformas Sociales. Consejo Económico Social, Madrid

Del Rey F (1992) Propietarios y patronos. La política de las organizaciones económicas en la España de la Restauración (1914–1923). Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Madrid

Domenech J (2011) Legal origin, ideology, coalition formation, or crisis? The emergence of labor law in a civil law country, Spain 1880–1936. Labor Hist 52(1):71–93

Elu A (2010) Las pensiones públicas de vejez en España. In: Pons J, Silvestre J (eds) Los orígenes del Estado del Bienestar en España, 1900–1945: los seguros de accidentes de trabajo, vejez, desempleo y enfermedad. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, pp 1908–1936

Espuelas S (2012) Are dictatorships less redistributive? A comparative analysis of social spending in Europe (1950-1980). Eur Rev of Econ Hist 16(2):211–232

Espuelas S (2013a) Los obstáculos al desarrollo de los seguros sociales en España antes de 1936: el caso del seguro de desempleo. Rev de Hist Indust 52:77–110

Espuelas S (2013b) La evolución del gasto social público en España. Estudios de Historia Económica. Banco de España, Madrid

Espuelas S (2015) The inequality trap. A comparative analysis of social spending between 1880 and 1930. Econ Hist Rev 68(2):683–706

Eza, Luis de Marichalar and Monreal, Vizconde de (1914) La previsión como remedio a la falta de trabajo. Conferencia dada en la Casa del Pueblo de Madrid el día 15 de febrero de 1913. Imprenta Bernardo Rodríguez, Madrid

Girón de Velasco JA (1943) Escritos y discursos. Ediciones de la Vicesecretaria de Educación Popular, Madrid

Girón de Velasco JA (1951) Quince años de política social dirigida por Franco. Ediciones OID, Madrid

González F, Oyuelos R (1914) Bolsas de Trabajo y Seguro contra el Paro Forzoso. Publicaciones IRS, Madrid

Guillén A, Álvarez S (2004) The EU’s impact on the Spanish welfare state: the role of cognitive Europeanization. J Eur Soc Policy 14(3):185–299

Hellwig T (2005) The origins of unemployment insurance in Britain. A cross-class alliance approach. Soc Sci Hist 29(1):107–136

Hicks A (1999) Social democracy and welfare capitalism. A century of income security politics. Cornell University Press, London

INP (1936) La unificación de los seguros sociales, 3ª edición. Publicaciones INP, Madrid

INP (1952–57) Boletín de Información Estadística (3–21). INP, Dirección de servicios especiales, Asesoría actuarial, Madrid

INP (1960) Boletín de Información Estadística (30). INP, Dirección de servicios especiales, Asesoría actuarial, Madrid

Jerez A (1996) El régimen de Franco: elite política central y redes clientelares, 1938–1957. In: Robles A (coord) Política en penumbra. Patronazgo y clientelismo políticos en la España contemporánea. Siglo XXI, Madrid

Jordana L (1953) Los seguros sociales en España de 1936 a 1950. INP, Madrid

León M (2002) Towards the individualization of social rights: hidden familialistic practices in Spanish social policy. S Eur Soc Politics 7(3):53–80

León M, Salido O (2016) Políticas de familia en perspectiva comparada. In: León M (coord) Empleo y maternidad: obstáculos y desafíos a la conciliación de la vida laboral y familiar. FUNCAS, Madrid

Lindert PH (2004) Growing public: social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Malefakis EE (1970) Agrarian reform and peasant revolution in Spain: origins of the civil war. Yale UP, New Haven and London

Maluquer J (1926) Una campaña en pro del seguro y de la previsión popular. Publicaciones y Trabajos de Josep Maluquer i Salvador. Sucesora de M. Minuesa de los Ríos, Madrid

Maluquer J (2009) Del caos al cosmos: una nueva serie enlazada del producto interior bruto de España entre 1850 y 2000. Revista de Economía Aplicada 49(XVII):5–45

Maluquer J, Llonch M (2005) Trabajo y relaciones laborales. In: Carreras A, Tafunell X (coords) Estadísticas históricas de España. Fundación BBVA, Bilbao

Mares I (2003) The politics of social risk: business and welfare state development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Molinero C, Ysas P (1998) Productores disciplinados y minorías subversivas. Clase obrera y conflictividad laboral en la España. Siglo XXI, Madrid

Montero F (1988) Los seguros sociales en la España del siglo XX. Orígenes y antecedentes de la previsión social. Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Madrid

Moreno Luzón J (2007) Political clientelism, elites and caciquismo in restoration Spain (1875-1923). Eur Hist Q 37(3):417–441

Murray JE (2003) Social insurance claims as morbidity estimates: sickness or absence. Soc Hist Med 16(2):225–245

Murray JE (2007) Origins of American health insurance: a history of industrial sickness funds. Yale University Press, New Haven

Nicolau R (2005) Población, salud, y actividad. In: Carreras A, Tafunell X (coords) Estadísticas históricas de España: siglos XIX y XX. Fundación BBVA, Bilbao

Offer A, Söderberg G (2016) The Nobel factor: the prize in economics, social democracy, and the market turn. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Pérez Ledesma M (1990) Estabilidad y conflicto social. España, de los íberos al 14-D. Nerea, Madrid

Pons J (2010) Los inicios del seguro de enfermedad en España. In: Pons J, Silvestre J (eds) Los orígenes del Estado del Bienestar en España, 1900–1945: los seguros de accidentes de trabajo, vejez, desempleo y enfermedad. PUZ, Zaragoza, pp 1923–1945

Prados de la Escosura L (2003) El progreso económico de España (1850–2000). Fundación BBVA, Bilbao

Prados de la Escosura L (2008) Inequality, poverty and the Kuznets curve in Spain, 1850–2000. Eur Rev Econ Hist 12:287–324

Samaniego M (1988) La Unificación de los Seguros Sociales a Debate. La Segunda república. Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Madrid

Silvestre J (2003) Los determinantes de la protesta obrera en España, 1905-1935: ciclo económico, marco político y organización sindical. Revista de Historia Industrial 24:51–80

Silvestre J, Pons J (2010) El seguro de accidentes del trabajo, 1900-1935. El alcance de las indemnizaciones, la asistencia sanitaria y la prevención. In: Pons J, Silvestre J (eds) Los orígenes del Estado del Bienestar en España, 1900–1945: los seguros de accidentes de trabajo, vejez, desempleo y enfermedad. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza

Simpson J, Carmona J (2020) Why democracy failed. The agrarian origins of the Spanish civil war. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Torregrosa-Hetland S (2018) Limits to redistribution in late democratic transitions: the case of Spain. In: Huerlimann G, Brownlee WE, Ide E (eds) Worlds of taxation: the political economy of taxing, spending, and redistribution since 1945. Palgrave, London

Tuñón de Lara M (1972) El movimiento obrero en la historia de España. Taurus, Madrid

Tusell J (2005) Dictadura franquista y democracia, 1939–2004. Crítica, Barcelona

Valiente C (1996) The rejection of authoritarian policy legacies: family policy in Spain (1975–1995). S Eur Soc Polit 1:95–114

Velarde J (1990) El tercer viraje de la seguridad social. IEE, Madrid

Vilar M (2004) Mercado de trabajo y crecimiento económico en España (1908–1963): una nueva interpretación del primer franquismo. Universitat de Barcelona, Dissertation

Acknowledgments

I thank Alfonso Herranz, Peter Lindert, Javier San Julián, Sara Torregrosa-Hetland, and the participants at the fifth Finland in Comparison Conference and the second Workshop on Public finance in the History of Economic Thought for their comments. Also acknowledged is Javier Silvestre’s patience and help. The usual disclaimers apply.

Most of all, I would like to thank John E. Murray. I met John in 2008, when he visited the University of Barcelona as a visiting scholar. At that time, I was in the early stages of my PhD. I distinctly remember John being kind enough to discuss with me what, at the time, were just a few research ideas and bits of data. He made a number of suggestions and even gave me some ideas on how to start publishing my work. My later research departed a bit from the preliminary ideas that I presented to John. But for me (a young scholar who was just starting out) it was very important that a professor from the United States listened to me and gave me advice on how to continue. Of his work, I followed with particular attention his studies on social insurance. I always found his book on the Origins of American Health Insurance to be an excellent example of combining quantitative and qualitative methods. I admired his ability to illustrate through examples and testimonies of the time some of the most relevant findings of the book, as well as the attention that John paid to the incentive problems associated to the design of social insurance. Some of the ideas I had the opportunity to discuss with him are captured in this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Espuelas, S. (2022). A Difficult Consensus: The Making of the Spanish Welfare State. In: Gray, P., Hall, J., Wallis Herndon, R., Silvestre, J. (eds) Standard of Living. Studies in Economic History. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06477-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06477-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-06476-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-06477-7

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)