Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals for adolescent female students enrolled in a multi-phased mentoring program in Armenia. The marginalization of girls from resource-poor settings, especially in a patriarchal society such as Armenia, is significant in both the access and support networks required to obtain a college/university degree. These social and environmental obstacles can be examined through an understanding of the personal, behavioral, and environmental factors that relate to girls’ aspirations, academic, specifically math and science, and career interests, and academic career goals. The current study analyzed these relationships through a framework derived from Social Cognitive Theory and Social Cognitive Career Theory. In addition, the importance of global citizenship is addressed, as the ways in which girls understand their roles in their local and global communities. Results indicated a strong correlation between academic interests and academic goals within the general population as well as subgroupings, providing insight into how programming addressing interests and goals could create positive outcomes. The research and conclusions drawn from this study have the ability to create a widespread impact on the knowledge of the effectiveness of a multi-phased mentoring program on female self-efficacy, the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals, the connection to global citizenship, as well as working to achieve SDG 4: quality education, 5: gender equality, and 10: reduced inequalities. Implications and recommendations are discussed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

7.1 Introduction

Traditional forms of education for girls in Armenia are lacking in key developmental elements related to the personal, social, and environmental aspects of career development and social support. The lack of curriculum focused on soft skills such as teamwork, communication, and decision-making (i.e., social support) and the strong emphasis on theoretical education without hands-on or practical application led to youth who emerge without the relevant skills required to achieve their career goals and meet workforce expectations (Allison et al. 2019). The last decade of educational reform in Armenia has shown an evolution of courses and curriculum that support equality in schools, educational attainment, and career readiness (Allison et al. 2019). However, the growth seen in education benchmarks for women is not mirrored post-education and within the labor force (USAID 2019). While USAID reported an alignment in male and female youth priorities toward financial security, rather than the traditional gender roles of women placing traditional matriarchal roles over positions in the formal labor force, issues related to environmental influences ingrained within communities and labor structures emerged as relevant variables influencing the lag of gender equality growth (Allison et al. 2019). Compounding these challenges are the expectations for girls in Armenia, especially in rural areas, that are laden with patriarchal stereotypes impacting career opportunities for young girls. Women and girls are limited by community leaders that lack progressive viewpoints or are unaware of the shift away from traditional goals or strong familial pressures shifting their daughters’ goals toward culturally appropriated life paths, especially if the girls are from vulnerable backgrounds, such as from a low income family, making them less likely to receive access to education reform and resource rollout and more likely to dropout earlier in their education (Allison et al. 2019).

These factors, among other social and environmental constructs, cause girls to experience a restricted range of efficacy-building experiences, leading to constricted career interests and goals (Lent and Brown 1996). In the Armenian context, with little resources inside or outside the classroom to combat these limiting factors and form foundational skills, there exists an opportunity to provide a space to facilitate strong career and academic interests, goal setting, and the cultivation and support of self-efficacy. For youth within and beyond adolescence (Leahy 2017), formal learning may not reach the most vulnerable populations due to drop out rates and quality of educational experiences (Allison et al. 2019). The opportunity to explore informal learning experiences, such as a mentoring program focused on strengthening self-efficacy, has the potential to foster clear interests and motivated choice goals that could make significant strides within the vulnerable youth of Armenia, while at the same time contributing to higher attrition rates and student support in secondary and post-secondary education.

It is with these variables in mind that this study explores the relationship between self-efficacy and interests for adolescent female students in Armenia. Specifically, the current study explores these relationships for students enrolled in the Nor Luyce multi-phased mentoring program. In addition, the study will examine how these relationships correlate with students’ choice goals for their future careers to answer the questions:

-

1.

In what ways does self-efficacy correlate with student career interests? Do self-efficacy and career interests relate to student choice goals related to career aspirations?

-

2.

How does self-efficacy correlate with student academic interests in science and mathematics? Do self-efficacy and academic interests relate to further academic goals such as higher education?

-

3.

How can Nor Luyce act as a vessel to promote Sustainable Development Goal attainment and capitalize on the relationships explored between self-efficacy, career and academic interests, and goals. What opportunities does Nor Luyce have to affect change and improvement within those relationships?

Research related to mentoring programs has made significant strides in determining the most successful pathway to promote growth toward sustained positive outcomes. More specifically, a triadic approach to mentoring, one that emphasizes improving “social skills and emotional well-being, cognitive skills through dialogue and listening,” and is facilitated through strong mentor/mentee relationships, is critical to the success of mentoring programs (Rhodes 2004, p. 35). Programs that emphasize these methods allow the mentee to remain the focus of the program while promoting a sustained relationship with their mentor built on mutual kindness and attentiveness. Rhodes and DuBois (2008) also highlight the importance of a consistent prolonged relationship and a connection built on mutual understanding and reliability to ensure a beneficial experience for the participating mentor. Direct and specific construction of mentor/mentee relationships is integral to ensuring the creation of strong positive outcomes for adolescents within a mentoring program (Rhodes and DuBois 2008).

7.1.1 About Nor Luyce

As the name suggests, Nor Luyce, Armenian for “new light”, strives to be a beacon for young girls from vulnerable backgrounds. The three phase mentoring program based in Gyumri, Armenia was created in 2009 after a local family visited an Armenian orphanage and noticed the lack of educational, financial, and social resources available to the children as well as the tendencies toward both complacent and regressive social norms and patriarchal views. From this visit, Nor Luyce was founded in an effort to create and provide educational, financial, and social resources for socially and financially vulnerable girls. During the last decade, Nor Luyce has cultivated a program that works to empower young girls in the community to become self-supporting, creative, strong, and thoughtful adults capable of reaching their desired personal and career goals. Each year, twenty-five 13–14-year old girls begin the first stage of the mentoring program. These mentees (i.e., participants in the program) come from one-parent households, two parent middle income households, two parent low income households, or no parent/caregiver local orphanages.

To begin, the three phased mentoring program provides mentors with initial training to ensure the best possible experience for both mentor and mentee. The pre-mentoring program allows the newly recruited volunteers to understand the expectations the title of mentor holds, their main role, best practices of a sustained successful relationship with a mentee, as well as helps them feel fully prepared to begin working with their mentee. The ongoing mentoring training allows mentors to receive continuous formal and informal support from trained staff members while continuing to cultivate their roles and gather information from their peers and from the staff on soft skills, trauma-specific responses, mentoring relationship ethics, and bond-building. Further, mentors continue to develop their skills to improve their ability to work with a mentee on strengthening self-efficacy and fostering clear academic and career interests and choice goals.

7.2 The Nor Luyce Program

The Nor Luyce Program comprises three phases: the Mentoring Phase, Skill Building Phase, and Higher Education Phase as shown in Table 7.1. The Mentoring Phase focuses on problem solving, emotional stability, the foundational construction of the mentee/mentor relationship, and creating the stepping stones for continued self-efficacy, goal setting, and interest acknowledgement and development. Personal growth is the cornerstone of the Mentoring Phase and continues to be fundamental in the next phase (i.e., Skill Building Phase) which emphasizes personal development in life, academic and professional skills, and expanding world views. During the higher education phase, Nor Luyce prepares the girls for life after the program through financial assistance and additional training on career or continued education opportunities. To give the mentees a look into how their goals may be realized in the future, successful Armenian women offer their time as guest speakers to narrate their own pathway to achievements and speak to how they overcame adversity. Throughout each of the phases Nor Luyce works to address the mentees’ areas of opportunity and further reinforce their strengths so the mentees are able to pursue their desired paths and step into their roles as the future of Armenia.

To date, Nor Luyce has helped over 173 girls emerge into strong young women. Throughout each phase, Nor Luyce focuses on improving self-efficacy in each mentee and provides them with the tools to build self-esteem and self-reliance to achieve their career, academic, and personal goals and become strong globally aware young women. Table 7.1 outlines the phases of the program and highlights the importance of both individual and group mentoring meetings and the important life skills such as communication, teamwork, conflict management, and self-esteem skills adolescents acquire while being a part of the program.

Built on previous findings in successful research to practice programming (Rhodes 2004; Rhodes and DuBois 2008), the Nor Luyce program strengthens self-efficacy and fosters strong interests and goals by creating consistent and extended relationships between mentor and mentee and putting mentee needs at the forefront of programming. This approach promotes the incorporation of integral aspects of successful mentoring programs to instill positive outcomes specifically for the Armenian context. Mentoring success is deemed as showing positive growth within success metrics corresponding to the goals of the specified program, thus Nor Luyce looks to self-efficacy, interest, and goal setting metrics. Rhodes (2004) notes that successful mentoring results “vary tremendously; [and results] are sometimes complex and subtle, and they may emerge over a relatively long period of time” (p. 50). Therefore, determining the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals for future careers and aspirations within the Armenian context as part of this study will provide contextually relevant findings, through an exploration of current mentoring structures and processes, to support the field as it continues to grow and foster female youth mentoring success.

7.2.1 Introduction to Global Citizenship Connection

Youth mentoring success, especially within the context of this study’s emphasis on self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals, should be explored through a framework and philosophy that incorporates an assessment of perceptions and ideas related to future goals and ideals (Betz and Hackett 1981). Using such a lens allows for a conceptualization of what impact understanding the evolution of global competency, self-efficacy, career and academic interests, and choice goals may have within the Armenian context as well as within a broader application to the development of global citizens. Global citizenship competency metrics and ideas align strongly with what Nor Luyce strives to instil within their mentees. Stanlick (2021) discusses the opportunity to incorporate a global citizenship curriculum (e.g., Oxfam) in order to promote knowledge on “globalization and interdependence and sustainable development” (p. 49). This aligns with Nor Luyce’s goal to expose the mentees to the mission of the UN and the changes it is seeking to bring. Through a passion for change that speaks to a broader audience, instilling an understanding of global interconnectedness and global opportunity within the program participants as they are exposed to the wider impact they and their program can have.

Efforts to incorporate global citizenship development and education are defined by Oxfam as “encouraging young people to develop the knowledge, skills, and values they need to engage with the world” (Oxfam GB 2021, p. 1) within Nor Luyce programming encourages the promotion of a holistic approach to self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals and helps participants understand the importance of all steps, small and big, toward the realization of gender equality and quality education locally and globally, strongly aligning with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The topics Nor Luyce covers are diverse, including the UN and the SDGs- which are espoused through Nor Luyce’s consultative ECOSOC status, the highest status that allows organizations to participate in the work of the UN, (NGO Branch Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2018). In addition, issues related to discrimination, professions without prescribed or explicit gender roles, public skills, human rights, and exposure to customs and traditions in other cultures, allow and encourage the girls to gain a fundamental understanding related to the importance of educating themselves and others. Through the program, the mentees can conceptualize that, while their location impacts their daily lives, it does not constrain their voices from being heard. The opportunity to engage with the UN and other international and global entities provides the participants with the experience and understanding that they can make an impact within the UN, a prominent measure of global citizenship competency (Stanlick 2021). Furthermore, fostering strong, “critical thinking… co-operation, and conflict resolution skills” while encouraging self-esteem and identity growth are integral focuses both within Nor Luyce and achieving global citizenship competency (Stanlick 2021, p. 49). Global citizenship skill development plays an active role in the promotion of self-efficacy, creating a strong connection between global citizenship and Nor Luyce’s mission and curriculum.

7.2.2 Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals and Global Citizenship

To foster an environment capable of producing globally aware advocates for gender equality and quality education, Nor Luyce emphasizes the importance of a foundation of strong self-efficacy, generally defined as how self-beliefs are able to affect outcomes and the outcome process (Bandura 1989; Gibbons and Shoffner 2004; Lent and Brown 1996) to ensure development and growth of self-respect, respect for others, academic and career interests. These efforts are directly related to achievable goals, community engagement, inclusivity, justice, effective communication, responsibility, and basic life and academic skills—paralleling aspects of the fundamentals of global citizenship education (GCED) and the concept of lifelong learning, “a process of deliberate learning that each person conducts throughout his or her lifetime” (Knapper and Cropley 2000, p. 1; Oxfam GB 2021). Informal educational experiences, such as the ones provided by Nor Luyce, are the stepping stones to creating a pattern of lifelong learning (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2019).

Not only does this exploration of Nor Luyce’s multi-phased mentoring program note the connection to global citizenship and the potential to promote global citizenship development, but also the possibility to progress additional global goals focused on education, gender equality, and reducing inequalities as outlined in SDGs 4, 5, and 10. Because Nor Luyce has gained UN accreditation and is in consultative status with ECOSOC, the NGO has integrated global channels designed not only to gain continued knowledge about the international community’s progress and innovation on mentoring in general and additional research on self-efficacy development and relationships with interests and goals, but also the opportunity to play an integral role in furthering the SDGs and subsequent targets through sharing the results of relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals and mentoring programming through an Armenian lens.

The SDGs provide critical solutions to global problems through global partnerships to create, “a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future” (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development, p. 1). This study’s focus aligns with three sustainable development goals, SDG 4: Quality Education, SDG 5: Gender Equality, and SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities. Under those goals, the specific targets that our research and outcomes emphasize are as noted in Table 7.2: 4.5, 4.7, 5.5, 5.b, 5.1, and 10.2.

In order to progress toward achieving the targets outlined in Table 7.1, Nor Luyce also subscribes to the fundamental goal of providing girls from vulnerable backgrounds with informal learning experiences in order to empower each girl to lead a life of purpose, driven by aspirations and goals. Through the UN, Nor Luyce is connected with a network of organizations across the globe that are striving to achieve the SDGs that align with the NGO’s mission to provide adolescent girls the means to become self-sufficient, healthy, globally aware young women who have set personal and career goals and who have created an action plan of how to achieve them. With Nor Luyce’s partnerships as well as its strong connection to a foundation of global citizenship through GDED programming alignment, the research and conclusions drawn from this exploration of the effectiveness of a multi-phased mentoring program on female youth self-efficacy, the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals have the ability to act as a stepping stone toward achieving sustainable development goals 4, 5 and 10.

7.2.3 Framing Global Citizenship and Self-efficacy, Interests, and Choice Goals

To construct a framework that suits Nor Luyce’s focus on adolescent females enrolled in a multi-phased program in Armenia to explore and determine the effectiveness of a multi-phased mentoring program on female self-efficacy and the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals, this study aligns with Social Cognitive (SCT) and Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) (Bandura 1989; Lent et al. 1994). Through these frameworks, this study will hone in on self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals. As SCT and SCCT highlight, Nor Luyce initially focuses on learning about and determining the impact of environmental factors in order to acknowledge strengths, areas for growth, and a successful plan of action forward (Bandura 1986; Lent and Brown 1996). With that knowledge, Nor Luyce then moves to providing informal learning experiences through group and individual meetings to encourage the promotion of self-efficacy. As self-efficacy grows, the mentees are then encouraged to utilize those skills to strengthen their interests and to foster measurable and attainable goals. Thus, Nor Luyce’s process expects to see shifts in interest and choice variables with strengthened self-efficacy that are parallel to shifts expected within SCCT (Lent and Brown 1996). Gaining knowledge on the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals promote further validation of the frameworks and reasoning of SCT and SCCT.

7.3 Literature Review

7.3.1 Mentoring as a Construct

Rhodes and DuBois (2008) explain that a sustained positive outcome of mentoring programs is not always seen, necessitating the creation of programming that provides consistent support to both the mentor and mentee as well as requires a consistent relationship between the mentor and mentee for a prolonged period of time. This fosters the formation of strong bonds between the mentor and mentee, and thus the promotion of mentee growth. Mentoring “has also recently been identified as a mechanism that can potentially support marginalized individuals within organizations” thus pointing toward the possibility of positive outcomes for specific population groups (Roland 2008, p. 56). Orphaned girls and girls from resource-poor backgrounds are particularly vulnerable to social and psychological problems which creates an important space for informal learning experiences (Lata and Shukla 2012) to make an impact and provide a place for personal growth. To create the most successful and lasting improvement in a mentoring program, Reagan-Porras (2013) explains that, “the mentor mentee relationship should (a) last more than one year (b) be based on shared interests; (c) consist of regular consistent face-to-face meetings; (d) and be child centered in that youth should view the mentor as a trusted friend and not as an authority figure” (p. 210), aligning with Rhodes and DuBois’s (2008) research and discussion on the importance of the creation of a consistent, sustained, and mentee focused mentor/mentee relationship. Creation of an individualized mentor relationship with those characteristics can positively impact “social-emotional, cognitive, and identity-related developmental processes” (Rhodes and DuBois 2008, p. 255). Working individually as well as incorporating a group aspect into mentoring programming provides adult guidance and the ability to target each mentee’s needs as well as peer interaction and social growth (Herrera et al. 2002). Herrera et al. (2002) also shed light on the positive impact group mentoring can have on behavioral skills, peer and adult relationships, and academic performance that may be more difficult to achieve with purely individual meetings. Utilizing a group and one-on-one meeting approach creates individualized programming that also addresses and fosters social and relational growth.

7.3.2 Nor Luyce Mentoring Structure

Nor Luyce integrates the Reagan-Porras (2013) model focused on individualized relationships outlined above and integrates group meetings into the programming in order to highlight the behavioral, peer and adult relationship, and academic performance benefits of group mentoring outlined in Herrera et al’s. (2002) research. The Nor Luyce program begins with a mentor–mentee relationship that lasts approximately 1 year. The mentor–mentee grouping is a mutual selection process to ensure initial trust and a solid relationship throughout the program. Because of the mentee-mentor mutual selection process and mentor training, the relationship created between the mentor and mentee is not one of strict authority but instead one of openness, kindness, and growth, removing barriers between the mentee and mentor and fading the stigma of an authority figure. The mentees individually meet with their mentors a minimum of 4 times a month for 11 months (approximately 44 meetings) during the Mentoring Phase. Group meetings are scheduled in advance and occur each week. To create a distinct pattern of consistency, individual meetings are carried out throughout the whole first phase while group meetings are continued throughout each phase of the program. Both group and individual meetings are scheduled to be conducted in person to secure the benefits of consistent face-to-face discussion, though due to COVID-19 this was not possible. However, regular programming was continued online and in person when possible. In person meetings were completely reinstated when restrictions were lifted on July 14, 2020, thus exhibiting that Nor Luyce’s mentoring program is continuing to align with the general suggested mentoring practices of consistency, longevity, and depth.

7.3.3 Social Cognitive Theory

Nor Luyce’s informal learning experiences strive to foster the creation of a foundation of strong self-efficacy to support career and academic interests and develop aspirational and achievable goals. Social Cognitive Theory explains the pathway between interconnectedness and learning experiences that exist within self-efficacy expectations, interests, and choice goals. Social Cognitive Theory is a structure of triadic reciprocal causality that “explains psychosocial functioning,” in which, “behavior, cognitive, and other personal factors and environmental events operate as interacting determinants that influence each other bidirectionally” (Wood and Bandura 1989, p. 361). To change unwanted behaviors or improve positive behaviors, Bandura (1999) notes three styles of possible information dispersion: personal networks that result in one being influenced by their social connections, gaining of knowledge through learning experiences, and strengthened perceived self-efficacy. Each of the information dispersion channels plays an integral role in creating positive improvements within self-efficacy, career and academic interests, and goal setting. Lim (2008) shows the impact of providing consistent global citizenship-focused learning experiences that resulted in improved perceived self-efficacy. Not only do learning experiences provide statistically significant results in academic motivation and commitment, but participants’ self-efficacy showed improvement as well, affirming the importance of positively altering behaviors through learning experiences and improved self-efficacy (Lim 2008). His conclusions support the foundational knowledge and skills Social Cognitive Theory presents that align with the promotion of learning experiences within mentoring programming and the overarching application of a global citizenship framework to Social Cognitive Theory. Social Cognitive Theory highlights that while some aspects of life, such as the surrounding environment, are unable to be controlled or changed, development from that point is greatly affected by human agency and specifically self-efficacy (Bandura 1999). The idea that “people are agentic operators in their life course, not just onlooking hosts of brain mechanisms orchestrated by environmental events” is an important mindset that emphasizes how fundamental self-efficacy is in the model (Bandura 1999, p. 22). Self-efficacy development allows for the opportunity to overcome stress, anxieties, and depression, as well as become more successful in setting and adopting goals, more flexible and empowered in an environment, and “remain resilient to the demoralizing effects of adversity” (Bandura 1999, p. 28).

7.3.4 Social Cognitive Career Theory

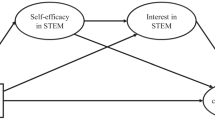

Derived from the Social Cognitive Theory, Social Cognitive Career Theory utilizes the theory of triadic reciprocal causation as well but, “highlights three intricately linked variables through which individuals help to regulate their own career behavior: self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and personal goals” (Lent and Brown 1996, p. 312). Self-efficacy is the most central of the three and as Bandura’s SCT emphasizes the importance of learning experiences, the surrounding environment, and social interactions as influential in the self-construction of self-efficacy and therefore, life outcomes (Gibbons and Shoffner 2004). The visual representation of Lent and Brown’s framework in Fig. 7.1 exhibits the connections between learning experiences, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, interests, choice goals, and performance results as well as their connections to environmental influences and personal inputs. SCCT describes a pathway from personal inputs such as gender (i.e., person inputs) to self-efficacy and outcome expectations which are strengthened and modeled through learning experiences. Self-efficacy and outcome expectations then influence interests which move into choice goals, actions, and finally performance. (Lent and Brown 1996). SCCT is aligned with the overarching theme of global citizenship and global citizenship education as it is necessary for “education to be based on the actual life experience of the individual to accomplish its purpose or goals” (Dewey 1938). Dewey’s thoughts and practices mirror SCCT, as it postulates that the connections between learning experiences, self-efficacy, interests, choice goals, etc. are fundamentally linear with a foundation of personal inputs, background environmental influences, and proximal environmental influences. Thus, gaining theoretical understanding of the relationships between self-efficacy, career and academic interests, and goal setting through SCCT provides a strong foundation to the creation of a framework exploring those relationships within Nor Luyce and the Armenian context.

Social cognitive career theory (Lent et al. 1994)

7.3.5 Self-efficacy

Determining the relationship between self-efficacy, interests, and goal setting for female students enrolled in a multi-phased mentorship program in Armenia requires a firm grasp of the fundamentals of self-efficacy. Bandura (1989) explains that “self judgments of operative capabilities function as one set of proximal determinants of how people behave, their thought patterns, and the emotional reactions they experience in taxing situations,” thus coming to the conclusion that the system of self-belief is fundamental to personal agency and decision making (p. 59). Self-efficacy is defined by Gibbons and Shoffner (2004) as one’s belief in their ability to achieve a goal as well as their confidence during the process. Lent and Brown (1996) take another approach, defining self-efficacy as ever-changing and dynamic “self-beliefs that are linked to particular performance domains and activities such as different academic and work tasks” able to be modified and affect formation of interests, goals, and behaviors (p. 312). Each highlights the impact one’s beliefs about themselves are able to have on an outcome. Pajares (1996) explains how “efficacy beliefs help determine how much effort people will expend on an activity, how long they will persevere when confronting obstacles, and how resilient they will prove in the face of adverse situations” (p. 544). While they all discuss the damaging effects of weak self-efficacy, collectively they shed light on the idea that those with low self-efficacy are more likely to experience depression, have lower expectations and goals, and higher stress and anxiety. In turn, this solidifies the importance of a self-efficacy focus as an integral part of ensuring positive outcomes within a mentoring program, as many of the Nor Luyce mentees come from vulnerable backgrounds that have greatly affected their emotional understanding, subjected them to strong adversity, or aided in the development of unhealthy coping mechanisms. While one cannot successfully complete complex tasks with strong self-efficacy and no ability, consistently improving self-efficacy allows for the possibility to shape experiences and outcomes (Lent and Brown 1996). Self-efficacy is a cornerstone within SCT and SCCT when addressing the connections between learning experiences, interests, and choice goals.

7.3.6 Interests

Self-efficacy directly impacts interests. When people believe they can do something well and understand how to overcome the obstacles they may face, they are more likely to develop an interest in that particular area of career development or academic study (Lent and Brown 1996). The reverse relationship, restricted interests resulting from low self-efficacy, is also true. Lent and Brown (1996) explain that “many people experience narrowed career interests either because they have been exposed to a restricted range of efficacy-building experiences or because they have developed inaccurate occupational self-efficacy or outcome expectations” (p. 314). A possible source of self-efficacy restrictions or inaccuracy stems from gender stereotyping or discrimination. SCCT addresses gender stereotypes and how social learning experiences can help to develop strong self-efficacy in polarized sectors when there is a strong difference in societal gender roles (Betz and Hackett 1981; Lent and Brown 1996). Counteracting the intense stereotypes with pointed learning experiences provides a way to deviate the pressure environmental influences have on a person’s self-efficacy and interests. With the introduction of a learning experience that alters self-efficacy in a positive progressive way, interests are then able to be developed with a less stereotypical and more clear mindset. This process is paramount in providing an educated and unbiased local and world viewpoint. Without grounded self-efficacy, it is difficult to develop strong academic or career interests, reiterating the importance of a positively evolving self-efficacy state when working to overcome social or environmental barriers to interest development. Secured self-efficacy and developed interests then act as a foundation for the creation of focused and achievable yet ambitious goals.

7.3.7 Choice Goals

A strong set of interests can encourage and lead to subsequent positive growth within goal setting, but interests are not the only variable affecting the creation of goals. SCCT explains how there may be environmental or social constraints to a pure relationship between interests and creation of goals as well as from direct effects from self-efficacy levels (Lent and Brown 1996). Lent and Brown (1996) explain that understanding a career path or specified goal will require encountering an uplifting, barrier-free, and easygoing environment is more likely to lead interests to expand into goals. While having a strong interest is the foundation, traversing an aggressive or difficult environment to achieve the goals related to the initial interest significantly stunts the formation of goals. Providing financial, social, emotional, and educational resources to combat potential obstacles while setting and achieving goals is paramount to seeing positive outcomes, creating a window of opportunity for a mentoring program to provide the resources and support needed. Ensuring the evolution of self-efficacy within programming is another integral resource to goal-setting growth, as self-efficacy and outcome expectations have the ability to directly influence choice goals. If a person believes a goal is attainable and will create a positive outcome, he or she is more likely to continue the activity and set the goal and work to achieve it (Lent and Brown 1996), thus leading to the conclusion that the pathway between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals is not directly linear but incorporates self-efficacy within each step, emphasizing the importance of a self-efficacy focused programming.

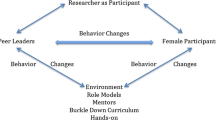

7.3.8 The Nor Luyce Framework

Social Cognitive Theory and Social Cognitive Career Theory have previously been used for mentoring research and analysis. Lent and Brown (1996) suggest that Social Cognitive Career Theory “offers some useful implications for designing developmental, preventive, and remedial career interventions,” thus providing the fundamentals of a framework that fits the Nor Luyce mentoring program (p. 319). For the purpose of the organization as a whole, the SCCT framework is modified to include previous skills as shown in Fig. 7.2. However, to address the research questions, this study will look specifically at the learning experiences, self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals sections of the modified framework as shown in Fig. 7.3.

Many of the girls in Nor Luyce deal with hardship and strive to overcome adversity in their environment, pointing to the value of providing a program to strengthen self-efficacy. Because of the core position of self-efficacy in SCT and SCCT, the Nor Luyce framework strongly aligns with both frameworks. As SCT and SCCT emphasize, Nor Luyce focuses on learning about, and determining how, participant environments have impacted them in order to create programming focused on individualized needs and initial levels of self-efficacy, interest development, and goal setting abilities. Following the path of SCCT, once environmental influences have been taken into account, learning experiences begin. Nor Luyce provides informal learning experiences throughout the program in two forms: group and individual. SCT discusses multiple ways to diffuse information and adjust negative behaviors, (Bandura 1999) which Nor Luyce incorporates into their group and individual meetings. During the group and individual meetings, Nor Luyce combines the learning experience itself with opportunities for the mentees to gain new social and emotional knowledge in order to introduce building self-efficacy. The meetings are an environment where the mentees are influenced by positive role models and consistent self-efficacy strengthening activities and discussions are highlighted. This practice incorporates each one of Bandura’s (1999) three styles of possible information dispersion: personal networks that result in social connection influence, learning experiences, and strengthened perceived self-efficacy to develop self-efficacy and form evolved career and academic interests and goals.

There is also a larger application of the community building Nor Luyce implements as “the problems we need to solve—economic, environmental, religious, and political—are global in their scope” (Nussbaum 2010 p. 79). Introducing the sense of community and interconnectedness into learning experiences provides the mentees with the opportunity to work on local problems that are applicable globally. Exposing the mentees to the alignment their Nor Luyce programming has with Sustainable Development Goal attainment and an overall more globalized world instills an understanding of how educating themselves and others have the potential to make a sustained impact within their environment. Informal educational experiences, such as the ones provided by Nor Luyce, are the stepping stones to creating lifelong learning. As each mentee’s self-efficacy strengthens through the learning process, the girls are able to form stronger interests and more ambitious goals. Because women, especially in a strong patriarchal society such as Armenia, are faced with many stereotypes and narrow expectations, combating them is a pressing issue. Sklad et al. (2016) emphasize the importance of addressing these issues in developing a global citizenship program, as it is critical to promote the dismantling of stereotypes in order to promote true global citizenship opportunities.

The concepts and values of global citizenship not only apply globally but also locally with programs like Nor Luyce that provide girls with opportunities regardless of gender norms or stereotypes that may be prevalent in their environment. The program focuses on taking the mentee’s previously strengthened self-efficacy and evolving it into expanded interests. Once interests are set in place, Nor Luyce provides the mentees with tools to formulate realistic yet ambitious goals, empowering them to exit the program with positive outcomes. This modified framework exhibits a pathway to empower young girls from orphanages or low income families through learning experiences to lead self-sufficient lives and impact the future by achieving their career and personal goals, improve their self-reliance, and emerge into strong young women.

7.4 Methodology

7.4.1 Participants

All participants are Armenian females, 13–14 years of age, participating in the Nor Luyce mentoring program. The girls come from one-parent households, orphanages, two-parent households with low socioeconomic status, or middle-class two-parent households. To explore the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals within the program participants the girls were categorized into 2 groups: those that responded to the question “How do you feel for the future career steps” with “confident” and those who did not select “confident”. This distinction was chosen to provide a relatively even distribution of participants. Of the 30 participants, 19 selected “confident” and 11 did not select “confident” (Table 7.3) providing a basis to look for connections between the two groupings and their responses to additional self-efficacy, academic and career interest, and goal-setting questions.

Measures

To explore the relationship between self-efficacy and interests, this study identified 32 questions from the Nor Luyce Pre-Evaluation and Pre-mentoring phase surveys conducted as an internal organizational assessment. These surveys are meant to be taken before entrance into the program or any exposure to informal learning experiences and then after the conclusion of the program to show areas of growth and improvement. The current study examined the results of participants entering the program for the first time. The pre-mentoring and pre-evaluation surveys included items to measure participants’ overall self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals. The questions were reviewed for content validity by both a mentoring expert and a SCCT expert.

7.4.2 Self-efficacy

Twelve self-efficacy questions were analyzed to gain foundational understanding of how self-efficacy is expressed within the Nor Luyce participants and the initial levels of self-efficacy development. Each self-efficacy question required a yes/no response where yes was coded as 0 and no at 1. For example, questions included “do you believe you can overcome your weaknesses?” and “do you feel confident in yourself?”. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale of self-efficacy was 0.74 (Table 7.4). While the authors understand the low reliability, as this is the first scale of its kind in Armenia, we moved forward with the analysis as prescribed to gain further insight into self-efficacy in the Armenian context.

7.4.3 Interests

To determine academic interest levels nine questions focused on science and math from the TIMSS student questionnaire including the questions “I look forward to mathematics class” and “I enjoy learning science”. The academic interest questions were coded on Likert scales from 1, agree a lot, to 5, disagree a lot. The academic interest questions centered on science and math to align with the focus and broader application of the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, TIMSS (National Center for Education Statistics). Three questions were reverse coded to ensure positive and responses aligned for each question. Cronbach’s alpha for academic interests was 0.72 (Table 7.5). As noted above, the authors recognize the low reliability for this scale, but chose to move forward with the analysis given the lack of understanding of interests for girls in Armenia.

To determine career interests the question “What would you like to have as a career?” was asked. The responses were coded into categories in which 1 indicated STEM, 2 indicated arts and humanities, 3 indicated technical or vocational, and 4 indicated other (Table 7.6).

7.4.4 Choice Goals

Four questions from the TIMSS student questionnaire including “It is important to do well in science” and “I think learning Mathematics will help me in my daily life” as well as an additional question “How far in your education do you expect to go?” analyze the mentees’ current academic goals. All five questions are on a 1–5 scale. The questions drawn from the TIMSS questionnaire are assessed on a Likert scale with 1 indicating agree a lot and 5 indicating disagree a lot (Table 7.8). For the additional question “How far in your education do you expect to go?” 1 represents the highest degree, completion of a doctoral degree, and 5 represents completion of high school or below (Table 7.7). Cronbach’s alpha for academic goals was 0.7. As noted above, the authors recognize the low reliability for this scale, but chose to move forward with the analysis given the lack of understanding of choice goals for girls in Armenia.

To determine career goal-setting levels, the question “Do you know which field you are going to develop your career towards?” was asked. The responses were coded from 1 to 4 with 1 indicating “Yes I Clearly know what profession I am going to choose” and 4 indicating “No” (Table 7.9).

7.5 Data Analysis

A non-experimental exploratory correlational design will be used to analyze the secondary dataset to determine the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals. Because this study attempts to determine the relationships between self-efficacy and interests and choice goals, utilization of bivariate correlation is appropriate. Additionally, linear regression will be used to explore the relationship further and will allow a conclusion to be drawn on the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals.

7.5.1 Results

The data for both pre- and post-survey data were sorted and all participants completed all questions. To explore the relationships between self-efficacy, academic interests, career interests, academic goals, and career goals a scale was created for each variable. Whole population and subgroup T-tests were run to determine mean differences within the whole population as well as “confident” and “non confident” subgroups. The t-tests indicated statistical significance within the career goals variable while self-efficacy, academic interests, career interests, and academic goals were not statistically significant. The paired t-test results (Table 7.10) for all scales (self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals) and groupings (confident and non-confident) indicate that mentees who felt confident about their future career steps (confident subgroup) had slightly lower, and thus more positive academic interests, career interests, academic and career goal responses compared to mentees that felt non-confident about their future career steps (the only statistically significant relationship was seen in the career goals variable). Mentees that felt confident about their future career steps (“confident” subgroup) had slightly higher, and thus weaker self-efficacy compared to mentees that felt non-confident about their future career steps; however this observation was not statistically significant.

To further examine the relationship among the study variables for all research questions, Pearson correlation was computed among the scales for the total participants and then separately for confident and not-confident participants (Table 7.11). This allowed for an examination of the bi-directional relationships between the variables, with the correlation coefficient (r value) ranging from −0.63 to 0.25. The closer the r value is to 1 suggests a stronger relationship between the two variables (±). For example, academic goals within the general population as well as the confident population were significantly and positively correlated with academic interests, indicating that in the general population or within the confident subgroup, a higher academic goal response would likely mirror a higher academic interest response. Academic interests within the “non confident” population were significantly and negatively correlated with self-efficacy suggesting that stronger academic interests correlate with weaker self-efficacy. Though not significant, the general population and “confident” subgroup correlations were primarily positive and the “non confident” subgroup correlations were primarily negative.

To address each research question in depth, four regression analyses were run: self-efficacy predicting career interests, self-efficacy and career interests predicting career choice goals, self-efficacy predicting academic interests, and self-efficacy and academic interests predicting academic goals. The regression analysis of self-efficacy predicting career interests was positive, however not statistically significant for the whole group as well as the confident subgroup. The regression analysis of self-efficacy predicting career interests was negative, however not statistically significant for the non-confident subgroup, indicating that no statistically significant linear dependence of career interests on self-efficacy was seen within the population (Table 7.12).

The regression analysis coefficients of self-efficacy and career interests predicting career choice goals were positive, however not statistically significant for the whole group as well as the confident subgroup and non-confident subgroup, indicating that no statistically significant linear dependence of career goals on self-efficacy or career interests was seen within the population (Table 7.13).

The regression analysis coefficient of self-efficacy predicting academic interests was positive, however not statistically significant for the confident subgroup. The regression analysis of self-efficacy predicting academic interests was negative, however not statistically significant for the whole group, indicating no statistically significant linear dependence of academic interests on self-efficacy within the population as a whole or the confident subgroup. The regression analysis of self-efficacy predicting academic interests was negative and statistically significant for the non-confident subgroup, thus predicting that within the non-confident subgroup if self-efficacy increases by 1 on its scale, the academic interest metric is predicted to decrease by 0.628 (Table 7.14).

The regression analysis of self-efficacy and academic interests predicting academic goals predicted a negative but statistically insignificant relationship between self-efficacy and academic goals for the whole group, confident and non-confident subgroups. The regression analysis of self-efficacy and academic interests predicting academic goals predicted a positive but statistically insignificant relationship between academic interests and academic goals for the non-confident subgroup, indicating that no statistically significant linear dependence of academic goals on self-efficacy was seen within the whole population and each subgroup and no statistically significant linear dependence of academic goals on academic interests was seen within the non-confident subgroup. For the whole group and the confident subgroup, the regression analysis reported a statistically significant positive relationship between academic interests and academic goals, thus predicting that within the whole group, if academic interests increase by 1 on its scale and self-efficacy is fixed, the academic goals metric is predicted to increase by 0.621 and within the confident subgroup, if academic interests increase by 1 on its scale and self-efficacy is fixed, the academic goals metric is predicted to increase by 0.677 (Table 7.15).

7.6 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationships between self-efficacy, interests, and goals, specifically answering the questions:

-

1.

In what ways does self-efficacy correlate with student career interests? Do self-efficacy and career interests relate to student choice goals related to career aspirations?

-

2.

How does self-efficacy relate with student academic interests in science and mathematics? Do self-efficacy and academic interests relate to further academic goals such as higher education?

-

3.

How can Nor Luyce act as a vessel to promote Sustainable Development Goal Attainment and capitalize on the relationships explored between self-efficacy, career and academic interests, and goals. What opportunities does Nor Luyce have to affect change and improvement within those relationships?

7.6.1 Self-efficacy, Career Interests, Career Goals

Within the confident subgroup, mentees had more positive responses to career interests and goals within their respective scales compared to the non-confident subgroup. In addition, these mentees had lower self-efficacy responses compared to the non-confident subgroup; however, the t-tests did not indicate statistical significance within the self-efficacy and career interests variables, indicating that mentee subgroupings did not have a strong relationship to self-efficacy or career interests. However, they did indicate statistical significance within the career goals variable, pointing to the importance of non-confident and confident subgroupings within career goals and the importance of shifting mentees within the non-confident subgroup to the confident subgroup to potentially see more positive outcomes. To grow the mentee’s confidence in future career paths, Nor Luyce programming currently includes college visits and meetings with professionals that allow the girls to gain maximum knowledge about their future career from multiple perspectives. Nor Luyce greatly encourages the mentees and provides them with the resources to network with other professionals, participate in professional internships and volunteer work to improve their skills, build on their assets, gain experience and learn from notorious specialists. To further foster confidence growth, Nor Luyce staff emphasizes the importance of providing a safe place for the mentees, keeping communication open with the girls for them to feel comfortable reaching out for advice, and providing positive and constructive criticism for the girls to focus on positive behavior changes and not feel overwhelming disappointment when they face obstacles in their career path. Providing the mentees with important tools and techniques such as forming SMART goals, writing personal statements and academic journals, preparing a resume, giving speeches, preparing presentations, and searching for jobs and scholarships allow them to feel independent and well-prepared in making choices, decisions, or changes in their career paths throughout the lifelong learning process. Providing the girls with scholarships that will allow them to focus on their studies instead of being worried about finding the necessary funding to cover their tuition fee, especially in the first two years of their studies when they are still in the transition phase, is imperative in alleviating financial barriers to career path confidence, and thus moving mentees out of the non-confident category to see more positive outcomes.

Pearson’s correlation indicated all positive, though not statistically significant, correlations between self-efficacy, career interests, and career choice goals for the whole group and confident subgroup. Pearson’s correlation indicated a negative correlation between career interests and self-efficacy for the non-confident subgroup, however it was also not statistically significant. The correlation tests indicated that there was not convincing evidence of either a positive or negative correlation between self-efficacy, career interest, and career goal responses within any grouping. The regression analyses predicted a positive relationship between self-efficacy and career interests for the whole group and confident subgroup, a negative relationship between self-efficacy and career interests for the non-confident subgroup, and a positive relationship between self-efficacy and career interests and career goals for all groupings. However, the regression analyses did not produce statistically significant values, indicating that self-efficacy is not a strong predictor of career interests within this population, and self-efficacy and career interests are not strong predictors of career goals within this population and population subgroupings. The small sample size is a limitation to these conclusions. As more mentees complete the surveys as time passes and Nor Luyce expands, future research and data analysis should be conducted to explore the relationships between self-efficacy, career interests, and career choice goals further with a larger sample size.

7.6.2 Self-efficacy, Academic Interests, Academic Goals

T-tests indicated that there was little distinction between academic interest responses and academic goal responses within the confident and non-confident groups. The lack of significance within the t-tests focused on academic interest and academic goal variables indicate the subgroupings did not have a significant impact on variable responses. However, exploring the subgroups with a larger sample size may yield more informative results.

Pearson’s correlation indicated a negative, statistically significant correlation between academic interests and self-efficacy in the non-confident subgroup signifying more positive academic interest responses related to lower self-efficacy responses within mentees who were not confident about their future career path. Pearson’s correlation also indicated statistically significant positive relationships between academic goal responses and academic interest responses in the whole group and the confident subgroup signifying within the whole population and confident subgroup, if the mentee was confident about her future career path, a higher academic interest score would mirror a higher academic goal score.

Looking deeper into Pearson’s correlation, because self-efficacy, academic interest, and academic goal relationships were negative within the non-confident group and were positive within the confident group, but only two were statistically significant, further exploration of the values associated with the non-confident and confident subgroups with a larger sample size would provide insight into if the relationship between self-efficacy, academic interests, and academic goals is consistently positive when looking at mentees that are confident in their career path and if the relationship between self-efficacy, academic interests, and academic goals is consistently negative when looking at mentees that are non-confident in their career path. Upon further study, if these correlations are significant, Nor Luyce would be able to look deeper into why mentees who are confident about their future career path have a positive relationship between self-efficacy, academic interests, and academic goals, why mentees who are not confident about their future career path have a negative relationship between self-efficacy, academic interests, and academic goals, and how the NGO can assess its current programming strategies to see if a focus on moving mentees out of the non-confident grouping could lead to more significant positive outcomes as discussed above in the previous regression analysis.

Regression analysis also predicted a negative, but insignificant relationship between self-efficacy and academic interests for the overall population and non-confident grouping, a positive, but insignificant relationship between self-efficacy and academic interests for the confident grouping, a negative, but insignificant, relationship between self-efficacy and academic goals for each grouping, a positive but insignificant relationship between academic interests and academic goals within the non-confident subgroup, and a positive significant relationship between academic interests and academic goals for the whole group and confident subgroup, predicting that with strengthening of academic interests there is an increase in academic choice goals for the whole group and those who were confident in their future career path.

Looking deeper into the regression analysis, given academic interests significantly positively relate to academic choice goals for the general population and girls who are confident in their future career path, it is important to provide the girls with the means to reveal their academic interests. Nor Luyce programming encourages academic interest growth through various empirically valid tests and assessments, college visits, and revealing meetings with various professionals that allow the girls to be well-informed about various career paths and opportunities. Also, providing the girls with assistance in class preparation and homework motivates the girls to build on their interest toward school subjects. Given the statistical significance and that the academic interest and goal survey questions adapted from TIMSS focused on math science, Nor Luyce has the opportunity to play a key role in motivating girls to review and change their approach to the predominantly math and science-focused professions, to break the stereotypes of STEM being a “male” field, receive assistance in STEM subjects, listen to women success stories in STEM and envision their own, and visit STEM focused entities where they can see and participate in workshops, all to give the mentees the opportunity to assess their interest in STEM related fields without stereotypical societal pressures.

7.7 Conclusion

Findings from the current study suggest that within the mentee population, non-confident and confident career path feeling subgroupings are important within career goals scores. Within the whole group, stronger academic goal responses correlated with stronger academic interest responses and given an increase in the level of academic interests, level of academic goals is predicted to increase. Within the non-confident subgroup, stronger academic interests were correlated with weaker self-efficacy and given an increase in the level of self-efficacy, level of academic interest is predicted to decrease. Within the confident subgroup, stronger academic goal responses correlated with stronger academic interest responses and given an increase in the level of academic interests, level of academic goals is predicted to increase. The study points to the idea that a mentoring program utilizing informal learning experiences has the opportunity to create positive outcomes within the Armenian context by addressing interests and goals. A strong relationship between self-efficacy and career and academic interests and self-efficacy and career and academic goals was not seen, contrary to our expectations and prominent frameworks (SCT and SCCT), signifying that our sample size was too small to detect a positive or negative effect with significance. The small sample size of this study warrants further research and data analysis of a larger sample size to further examine the relationships between self-efficacy, career interests, academic interests, career goals, and academic goals within the Armenian context. As this is the first year mentees completed the evaluation surveys, additional exploration of self-efficacy, interests, and goals for each mentee throughout each phase of the program is integral to understanding how each phase of the informal learning experiences Nor Luyce offers affects self-efficacy, academic, and career interest, and academic and career goal growth. Resources and tools necessary for the growth of lifelong skills are currently provided to girls from the local community of Gyumri and from the nearest villages. However, there are a number of girls in border villages that need assistance and motivation to strengthen their self-efficacy, reveal their academic and career interests, and feel confident in their future academic and career paths as well. Therefore, Nor Luyce aims to recruit more girls from villages to provide them with an opportunity to feel empowered, confident in their future and strive for changes. As Nor Luyce grows, it has the opportunity to raise awareness of the importance of mentoring in a collectivistic culture both locally and internationally. Incorporating additional mentees into the program will lead to a deeper understanding of how self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals interact to create positive outcomes.

Through providing informal learning experiences focused on women empowerment, Nor Luyce can work toward eliminating gender disparities and motivate young girls, with the help of mentors, to feel inspired to try new fields of career, continue their education, and confidently build their own career paths, aligning with UN sustainable development goals 4 quality education, 5 gender equality, and 10 reduced inequalities. As Nor Luyce continues to provide programming to promote growth within those SDG missions, a stronger global viewpoint is instilled within the mentees, leading them to emerge from the program ready to assume an active role in their local and global communities, embodying the fundamental values of global citizenship and lifelong learning (Oxfam GB 2021). With the knowledge from this study and future studies on the exploration of self-efficacy, interests, and choice goals, Nor Luyce has the opportunity to expand and evolve its own program as well as continue to educate itself and others throughout the local and international community on how mentoring is best able to address the pressing issues young girls from vulnerable backgrounds face and best able to empower the girls to lead self-sufficient lives and impact the future by achieving their future academic and career goals.

References

Allison CA, YouthPower Learning, USAID, Jenderedian GJ, Sargsyan LS, Proctor HP, Jessee CJ (2019) Armenia youth situational analysis, October. https://usaidlearninglab.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/armenia_youth_situational_analysis_public.pdf

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ Prentice-Hall Inc

Bandura A (1989) Social cognitive theory. In: Vasta R (ed) Annals of child development. Vol 6. Six theories of child development. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp 1–60

Bandura A (1999) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Asian J Soc Psychol 2(1):21–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839x.00024

Betz NE, Hackett G (1981) The relationship of career-related self-efficacy expectations to perceived career options in college women and men. J Couns Psychol 28(5):399

Dewey J (1938) Experience and education. New York: Macmillan

Gibbons M, Shoffner M (2004) Prospective first-generation college students: meeting their needs through social cognitive career theory. Prof Sch Couns 8(1):91–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42732419. Accessed 31 Dec 2020

Herrera C, Vang Z, Gale LY (2002) Group mentoring: a study of mentoring groups in three programs. Public/Private Ventures, Philadelphia, PA. http://scholar.google.com.ezproxy.lib.lehigh.edu/scholar_lookup?hl=en&publication_year=2002&author=C.+Herrera&author=Z.+Vang&author=L.+Y.+Gale&title=Group+mentoring%3A+A+study+of+mentoring+groups+in+three+programs

Knapper CK, Cropley AC (2000) Lifelong learning in higher education, 3rd edn. Stylus Publishing

Lata S, Shukla A (2012) The effects of social skills training on young orphan girls. Soc Sci Int 28(1):27–40. https://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/effects-social-skills-training-on-young-orphan/docview/1010358623/se-2?accountid=12043

Leahy RL (2017) Cognitive therapy techniques: a practitioner’s guide (2nd edn). Child Family Behav Therapy 39(4):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2017.1375729

Lent RW, Brown SD (1996) Social cognitive approach to career development: an overview. Career Dev Q 12:401–417

Lent R, Brown S, Hackett G (1994) Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J Vocat Behav 45:79–122. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lim CP (2008) Global citizenship education, school curriculum and games: learning mathematics, English and science as a global citizen. Comput Educ 51(3):1073–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.10.005

National Center for Education Statistics. Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). IES NCES. https://nces.ed.gov/timss/

NGO Branch Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2018) Introduction to ECOSOC consultative status. United Nations. http://csonet.org/index.php?menu=30

Nussbaum M (2010) Citizens of the world. In: Not for profit: why democracy needs the humanities—Updated Edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton; Oxford, pp 79–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77dh6.10

Oxfam GB (2021) What is global citizenship. Oxfam. https://www.oxfam.org.uk/education/who-we-are/what-is-global-citizenship/

Pajares F (1996) Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Rev Edu Res 66(4):543–578. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1170653. Accessed 3 Mar 2021

Reagan-Porras L (2013) Dynamic duos: a case review of effective mentoring program evaluations. J Appl Soc Sci 7(2):208–219. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43615077. Accessed 3 Jan 2021

Rhodes JE (2004) Stand by me. Harvard University Press

Rhodes J, DuBois D (2008) Mentoring relationships and programs for youth. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 17(4):254–258. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20183295. Accessed 3 Jan 2021

Roland K (2008) Educating for inclusion: community building through mentorship and citizenship. J Edu Thought (JET)/Revue De La Pensée Éducative 42(1):53–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23765471. Accessed 28 Dec 2020

Sklad M, Friedman J, Park E, Oomen B (2016) “Going global”: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of global citizenship education at a Dutch liberal arts and sciences college. High Educ 72:323–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9959-6

Stanlick S (2021) Bridging the local and the global: the role of service learning in post-secondary global citizenship education. In: Aboagye E, Dlamini S (eds) Global citizenship education: challenges and successes. University of Toronto Press, Toronto; Buffalo; London, pp 41–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctv1hggkjt.6. Accessed 31 May 2021

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2019) Literacy and basic skills, January 11. UIL. https://uil.unesco.org/literacy

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. The 17 goals|Sustainable development. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

USAID, Banyan Global, Aidis RA, Balasanyan SB, Shahnazaryan GS (2019) Usaid/Armenia gender analysis report August 2019. https://banyanglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/USAID-Armenia-Gender-Analysis-Report-1.pdf

Wood R, Bandura A (1989) Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Acad Manag Rev 14:361–384. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1989.4279067

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hastings, M., Mikayelyan, S. (2022). Exploring Social Cognitive Outcomes of a Multiphase Mentoring Program for Girls in Armenia. In: Stanlick, S., Szmodis, W. (eds) Perspectives on Lifelong Learning and Global Citizenship. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-00974-7_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-00974-7_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-00973-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-00974-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)