Abstract

In this paper, the manuscript of Codex Madrid I, Leonardo da Vinci’s workshop drawings collection, are reviewed and the main mechanisms that appear in the aforesaid codex are analysed. The works of Leonardo and the Codex Madrid I, in particular, are placed in their historical context. A compilation of the 100 main drawings of the manuscript is made. This compilation illustrates the variety of mechanical elements and simple mechanisms of Codex Madrid I, forming, as a whole, a complete treatise on mechanisms, understanding mechanisms as basic elements of machines.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

On February 14th 1697, The New York Times published astonishing news: the American researcher Jules Piccus had found, by chance, two manuscripts with drawings, sketches and annotations by Leonardo da Vinci in the Spanish National Library in Madrid: the now named Codex Madrid I and Codex Madrid II [10]. This discovery contributed to enlarging the legend of Leonardo.

The current view of Leonardo da Vinci is that of a wise man, the prototype of a humanist man, characteristic of the Renaissance period. Leonardo is considered a great artist, scientist and inventor, though this last statement is not entirely true [7, 9]. Although Leonardo proposes the design of some original machines, their functionality is questionable and he didn’t manufacture and test the aforementioned machines [4, 6, 12].

However, it should be noted all the written and, above all, pictorial material that he bequeathed as a collection of the knowledge of his time, the Renaissance [20].

In this paper, we show the main mechanisms and basic elements of Renaissance machines compiled in the Codex Madrid I, which is Leonardo da Vinci’s main contribution to the history of machines and mechanisms [1, 4].

This paper aims to offer an analysis of Codex Madrid I, to relate the technology compiled in this Leonardo da Vinci’s work with other authors of his historical environment, and to give a current view of the aforementioned manuscript by selecting 100 drawings from the main basic machine elements or mechanisms, composing a comprehensive treatise about the mechanisms of Renaissance.

The written output about the life and works of Leonardo is immense, but this paper will only cite those documents that are direct references for making this work.

2 Codex Madrid I

In 1964, two manuscripts by Leonardo da Vinci of an incalculable historical-scientific-cultural value were found in the Spanish National Library in Madrid. Both manuscripts (Codex Madrid I and Codex Madrid II) embrace almost seven hundred pages of new Leonardo writings about topics architecture, geometry, mechanics or navigation [15, 22].

Codex Madrid I can be defined as a comprehensive treatise of Renaissance mechanics, with a great graphical, descriptive and engineering ability [5]. The pagination care of the sheets and the technical-mechanical drawings presupposes that Leonardo bound this work thinking of a possible treatise.

In Codex Madrid I, Leonardo drew and studied several mechanisms to get different kinds of movement: alternating, swinging and, even, predefined movements. This paper will focus on the drawings of Codex Madrid I and we will only refer to the rest of Leonardo’s work occasionally.

Although Leonardo da Vince wrote other treatises that included machine studies (Codex Atlanticus, Paris Manuscripts, …) Codex Madrid I is unique as it establishes the first case to deconstruct machines into basic machine elements or mechanisms (Leonardo da Vinci called them “elementi macchinali”) [18]. Leonardo presupposes the existence of a reader for his work and writes the scientific passage thinking about them. Had Leonardo actually published this work, it might have accelerated the development of machine design.

The Codex Madrid I contains close to 1000 drawings of machines and machine elements. Drawings are of great quality, as well as writing, the typical mannerist handwritten of Leonardo. Drawings are of high quality, clear and complete, and they contain studies about the funding concepts of modern Mechanics, it is to say, mechanisms or mechanical elements. These mechanisms are not Leonardo’s machines, which are more complex and have particular usages. However, Leonardo tried to prove that by using and combining these simple elements it can be obtained machines that perform a specific function. Writing is of great quality too, the typical mannerist handwritten of Leonardo [22].

The work can be dated between 1492 and 1497, in the first period of Leonardo in Milan (1482–1499). This is when Leonardo was in the prime of his life, he was living his fourth decade [15].

Codex Madrid I is a one-volume manuscript that consisted of 192 sheets originally (only 184 sheets are preserved today), double side and dimensions 215 × 145 mm. The main body is made up of 12 notebooks, all containing 8 double sheets. The third and fourth notebooks have lost some double sheets [15].

From the point of view of its content, it is a compilation of texts mainly from other Leonardo’s treatises. It also offers earlier texts about static and geometry [18].

3 Historical Scope

This paper aims to analyse the Codex Madrid I [11], placing the mechanical knowledge that contains in the historical context (the Renaissance) [14] and justifying the claim that it is the first known treatise where the main mechanisms and simple machines are compiled and studied.

The culture of the Renaissance is marked by the exaltation of the dignity of man, thought inherited from classical thinking: in Sophocles’s Antigone [21], it was said: ‘Wonders are many, and none is more wonderful than man’. The culture of the Renaissance took into account other topics: the exaltation of nature, the critical spirit, using reason as the fundamental instrument of any mental process, adding mathematics as a complement to literary thinking, leaving aside the principle of authority, appreciating the importance of experimental practice, etc.

Renaissance ideas were shared by the Italian intellectual elite of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Byzantine intellectuals that emigrated to Italy after the fall of Constantinople (1453) contributed to this school of thought [15].

The life and work of Leonardo da Vinci allow placing him within his historical dimension: the Renaissance spirit, both from a theoretical and practical point of view [4, 5].

Leonardo lived in one of the most cultured environments in the European Renaissance. He didn’t develop original comprehensive theories in the scientific field, but he was a persistent observer and a singular exponent of a time that changed the world. His contribution to the effective progress of the science of his time was not great, perhaps due to the scant diffusion of his writings. But he left testimony of his defence of experimentation as a method of intellectual work, his claim to technique and of machines as instruments of progress and, above all, their general conception of reality governed by the laws of necessity, pragmatism, reason and proportion. Leonardo tried to demonstrate the superiority of visual creation over literary text in his work [13, 15].

One of the most important innovations of the Renaissance was to resort to drawing as an instrument of demonstration and communication. Following this idea, the graphic conventions necessary to visualize machines and suggest their features were defined. This art of describing machines became an instrument of technical-scientific study. Leonardo da Vinci was not very original but maybe he is the greatest exponent of this art.

Leonardo intended to know nature. He tried to penetrate its secrets and formulate its laws, in an attempt to solve the infinite problems posed by nature.

As we have commented, the ‘Renaissance’ is characterized by the emergence of the so-called “engineers” that surpasses the category of “master of war machines”, as the craftsmen-builders of the Middle Ages used to be called [5, 18].

Leonardo can be classified as an ‘engineer’ and he knew the activities of the Engineers and Architects of ancient Rome as well as that of his predecessors in the Italian Renaissance. Analysing Leonardo’s manuscripts, it can be stated that Leonardo knew the work of Vitruvius [8], Filippo Brunelleschi, Taccola [2], Leon Battista Alberti or Francesco di Giorgio Martini [3, 5, 16].

If we talk about the first works of the ‘engineers’, we can start from the military treatise by Guido di Vigevano as the predecessor of the notebooks of the Italian engineers of the Renaissance, as well as the military-technical writings of the German school [14, 18].

Among the Italian engineers of the Renaissance, we can speak of up to two generations of Italian engineers to reach the time personified by da Vinci. Among the authors of the first generation, we find Filippo Brunelleschi, Taccola, Leon Battista Alberti or Giacomo Fontana [5, 18]. Preceding the second generation, we can cite Roberto Valturio or Francesco di Giorgio Martini, marking the definitive transition to the second generation, of which Da Vinci was a notable representative. These two authors preceded and coincided in time with Leonardo, even Leonardo collaborated in some of his Works [14, 18].

The case of Francesco di Giorgio Martini is significant because the importance of his career is dwarfed by that of Leonardo today, who was inspired by his work and copied his drawings [3, 16, 18, 19]. However, Francesco di Giorgio was a well-known engineer in Italy in the late 15th century, whose works were known and highly regarded. Leonardo did not have as much recognition as Francesco di Giorgio in his lifetime, moreover, let us remember that Leonardo’s manuscripts were not published until a long time later. In Leonardo’s defence, it should be noted that Francesco di Giorgio had been inspired by Toccola’s work [2, 18].

The next tables (Table 1 and Table 2) show the main authors and works about machines that came before and after Leonardo and his work. Table 1 shows the indications of F.C. Moon in [18] and Table 2 evolves the summary proposed by W. Lefèvre in [14].

If we talk about the importance of Leonardo da Vinci as an engineer, it can be said that he was endowed with immense curiosity but was scattered: he started many things and later abandoned them. It should be noted his ‘method’ and his detailed analysis of the machines, studying the simplest elements, of which the Codex Madrid I was his main work. Leonardo bequeathed an immense number of designs and studies of machines and mechanisms to History, but his contribution of technical innovations was minimal [12]. Furthermore, he did not leave pupils and his work did not begin to be published until the 19th century.

4 The Mechanisms of Codex Madrid I

Shortly time after the Codex Madrid was rediscovered in 1965, Ladislao Reti translated the text into English and showed that da Vinci had attempted to compile a basic compendium of machine elements [11].

Reti [20] compared the drawings of machine elements and mechanisms in Leonardo’s Codex Madrid I with the basic list of 22 constructive elements proposed by Franz Reuleaux in his 19th-century book on machine design “The Constructor”. More recently, Moon confirmed this list [18] and made an advanced study of the machine elements and mechanisms that Leonardo described in the Codex Madrid I, including a comparison with the works of Timoshenko [17].

On the following pages, a sequence of images with Leonardo’s simple machines is included, which serve as the basis for correctly interpreting machines as a set of mechanisms and machine elements. In these images, we can appreciate the great contribution of Leonardo’s studies to machines engineering as a science.

In these 100 drawings (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9), we can see 100 mechanisms and machine elements that Leonardo illustrated in the Codex Madrid I, several of which were aimed to be integrated into Leonardo’s watch design Project (Fig. 10). In the Tables (Tables 3a, 3b, 3c, 3d and 3e) the drawings are very briefly described.

5 Conclusions

Leonardo was a master of painting, delved into physics and anatomy, designed machines and buildings and planned cities, and left a huge written work. However, he protected or concealed his findings led to the opinion that much of Leonardo’s scientific-technical work was speculative or not original. In this paper, some of the main contributions of Leonardo da Vinci in the field of mechanism and mechanical elements have been shown and analysed.

After reviewing Leonardo’s Codex Madrid I, this paper focuses on studying the principles of generating solutions most used by Leonardo have been studied: inspiration by nature, the organic vision of mechanisms, analysis to decompose machines and synthesis for the integration of mechanical elements and mechanisms; the analogies between different machine elements, and the economy in the design by suppressing the superfluous. All these advances allowed his mechanical designs to be better than those of his contemporaries.

The works of Leonardo and the Codex Madrid I, in particular, are placed in their historical scope and we have noted that representative genial personalities like Leonardo da Vinci and several others, could reach the heights in the Theory of Machines and Mechanisms because of contributions by many others.

In these pages, reviewing the manuscript of Codex Madrid I, the most important drawings of machine elements and mechanisms are shown and described: A compilation of the 100 main mechanism drawings of the manuscript is made.

This images compilation illustrates the variety of mechanical elements and simple mechanisms that exist in Codex Madrid I, forming, as a whole, a complete treatise on mechanisms (under-standing mechanisms as basic elements of machines), representation of the knowledge of this matter in the late fifteenth century.

References

Bautista, E., Ceccarelli, M., Echavarri, J., Muñoz, J.L. (ed.): A Brief Illustrated History of Machines and Mechanisms. History of Machines and Machine Science, vol. 10. Springer, Dordrecht (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2512-8

Ceccarelli M.: Contributions of Mariano di Jacopo (il Taccola) in mechanism design. In: XXIII Congreso Nacional de Ingeniería Mecánica. Proceedings of XXIII CNIM, Jaén, Spain (2021)

Ceccarelli, M.: Contributions of Francesco di Giorgio in mechanism design. In: XXII Congreso Nacional de Ingeniería Mecánica. Proceedings of XXII CNIM, Madrid, Spain (2018)

Ceccarelli M.: Contributions of Leonardo da Vinci in mechanisms design. In: XXI Congreso Nacional de Ingeniería Mecánica. Proceedings of XXI CNIM, Elche, Spain (2016)

Ceccarelli, M.: Renaissance of machines in Italy: from Brunelleschi to Galilei through Francesco di Giorgio and Leonardo. Mech. Mach. Theory 43, 1530–1542 (2008)

Cerveró-Meliá, E., Ferrer-Gisbert, P.E., Capuz-Rizo, S.F.: Functional feasibility review of the technical systems designed by Leonardo da Vinci. In: Proceedings of 22nd International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Madrid (2018)

Cerveró-Meliá, E., Capuz-Rizo, S.F., Ferrer-Gisbert, P.: Leonardo da Vinci’s contributions from a design perspective. Designs 4, 38 (2020)

Ceccarelli, M. (ed.): Distinguished Figures in Mechanism and Machine Science. Their Contributions and Legacies, Part 3. HMMS, vol. 26. Springer, Dordrecht (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8947-9

Contreras M.A.: Leonardo da Vinci: Ingeniero. Ph.D. thesis. University of Málaga, Spain (2015, in Spanish)

Da Vinci, L.: (c. 1504). Códice de Madrid. Madrid. Biblioteca Nacional de España. http://leonardo.bne.es/index.html

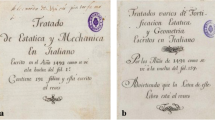

Da Vinci, L.: (c. 1500) Codex Madrid I or Tratado de Estatica y Mechanica en Italiano, 1493, Madrid. Facsimile Edition: The Madrid Codices, National Library Madrid, No. 8937. Translated by L. Reti. McGraw-Hill Book Co., 5 vols. (1974)

Gille, B.: Les ingénieurs de la Renaissance. Edited by Seuil (1978, in French)

Innocenzi, P.: The Innovators Behind Leonardo. Springer, Cham (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90449-8

Lefèvre, W. (ed.): Picturing machines 1400–1700. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2004)

Leonardo’s imaginary. Codices Madrid of the BNE. Edited by the Ministry of Culture, National Library (2012, in Spanish)

Merrill, E.M.: Francesco di Giorgio and the Formation of the Renaissance Architect. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Virginia (2015)

Moon, F.C.: History of dynamics of machines and mechanisms from Leonardo to Timoshenko. In: Yan, H.S., Ceccarelli, M. (eds.) International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms, pp. 1–20. Springer, Dordrecht (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9485-9_1

Moon, F.C.: The Machines of Leonardo da Vinci and Franz Reuleaux. History of Mechanism and Machine Science, vol. 2. Springer, Dordrecht (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5599-7

Moon, F.C.: The kinematics of Francesco di Giorgio Martini and Franz Reuleaux. In: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on History of Machines and Mechanisms, Moscow (2005)

Reti, L.: The engineer. In: Reti, L. (ed.): The Unknown Leonardo. McGraw Hill, New York (1974)

Sophocles (495-405 a.C.), Antigone. Ed. y trad. Hugh Lloyd-Jones, pp. 334–335. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, London (1994)

Two rediscovered manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci. The Unesco Courier. Published by UNESCO, October 1974

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Professors Emilio Bautista, Rafael López-García and Marco Ceccarelli for awakening the authors’ interest in the History of Machines and Mechanisms.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Rubio, H., Bustos, A., Castejon, C., Meneses, J. (2022). Analysis of the Codex Madrid I as a Compendium of Mechanisms. In: Ceccarelli, M., López-García, R. (eds) Explorations in the History and Heritage of Machines and Mechanisms. HMM 2022. History of Mechanism and Machine Science, vol 40. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98499-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98499-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-98498-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-98499-1

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)