Abstract

ACL graft tears pose challenges to both patients and surgeons. Multiple patient and technical factors need to be taken into account when deciding whether to embark on revision surgery. The intent of this chapter is to review the indications and contraindications to performing revision ACL surgery. Performing ACL revision surgery for the correct indications is critical to a successful outcome.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) occurs in up to 250,000 patients each year in the United States [1]. Annually, 175,000 to 200,000 primary reconstructive procedures (ACL-R) are performed [2]. Failure of ACL-R, as defined by pathologic knee laxity or graft rupture, occurs in 2–6% of patients undergoing primary ACL-R [3, 4]. Risk factors for ACL-R failure include male gender, return to sport, use of allograft during the primary reconstruction, and age younger than 25 years [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. When ACL-R fails, revision reconstruction is considered [12]. Satisfactory outcomes have been seen in 75–97% of patients undergoing ACL revision [13,14,15]. This chapter discusses the indications and contraindications for ACL revision reconstruction.

Indications

The indications for revision ACL reconstruction are listed in Table 3.1. It is important to note that not all patients experiencing a failed ACL reconstruction require ACL revision. The primary goal of a revision reconstruction is similar to a primary ACL reconstruction, that is, to restore functional stability to the knee. In addition to improving function, restoring knee stability protects the menisci and articular cartilage from injury.

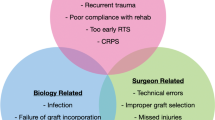

Failed ACL-R can be categorized as early (<1 year) or late (>1 year). Early failures frequently occur due to technical errors, failure of graft incorporation, premature return to activity, overly aggressive rehabilitation, or unrecognized concomitant injuries [8, 16,17,18,19]. Late (>1 year) failure is frequently associated with repeat trauma [7]. Knee instability resulting from ACL-R failure can lead to chondral injuries in both the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral compartments [7]. The Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS) group reported that 90% of knees undergoing revision ACL reconstruction had meniscal or chondral injury, with previous partial meniscectomy associated with a higher incidence of articular cartilage lesions [20]. ACL injury is associated with early-onset osteoarthritis [21,22,23,24]. Restoring knee stability, especially in the young, active patient with failed ACL-R, should be considered to potentially prevent further meniscal and chondral damage. Timing of revision reconstruction is a consideration. When compared to patients undergoing early revision (< 6 months), patients undergoing delayed revision (> 6 months) have a higher degree of articular cartilage damage [31].

In the athlete with a failed ACL-R, a discussion should be held regarding the chances of returning to sport and the difference between returning to sport and returning to preinjury level of activity. Although unpredictable, 49–75% of patients undergoing revision will return to some level of sport, but only 43% will return to their preinjury level of activity [33,34,34]. Return-to-sport rates are significantly lower when compared to return to sport following primary ACL-R [32]. However, revision ACL-R may yield the best chance of restoring knee stability [8] and provide athletes the best chance of return to competitive play.

Any patient with failed ACL-R undergoing meniscal repair or transplantation, articular cartilage repair or restorative procedures, or ligamentous reconstruction (PCL, PLC, PMC) should undergo concomitant or staged ACL revision reconstruction. Failing to address pathologic laxity related to ACL insufficiency significantly increases the likelihood of any of these procedures failing. [7, 26,27,28,29,30,30]

Contraindications

Several technical- and patient-related factors are associated with poorer outcomes and higher rates of failure after revision ACL reconstruction. Thus, it is important to identify these and consider them in surgical planning. A well-executed revision ACL that restores biomechanical stability may meet objective measures of success and yet still fail clinically. Firm contraindications to revision ACL surgery include active infection and significant knee stiffness/arthrofibrosis. The latter of the two is particularly relevant given that over 50% of patients undergoing revision ACL reconstruction report a history of trauma as the cause of their recurrent instability [2]. A summary of contraindications to revision ACL reconstruction are listed in Table 3.2.

The goal of revision ACL surgery is restoration of functional knee stability, and the patient’s goals should be clearly defined prior to the procedure. Older individuals with lower functional demands may not benefit from the procedure, especially if they are not having functional instability. Patients pursuing the procedure for pain-related purposes should be counseled accordingly, and this should be clearly addressed in any patient with symptomatic arthritis, obesity, or regional pain syndromes. Articular cartilage damage (grade 2 or greater) is independently associated with inferior clinical outcomes [10, 35]. Thus, regardless of the surgeon’s technical skill and expertise, the presence of symptomatic chondrosis may negatively impact the final outcome.

At baseline, revision ACL surgery has 3–4 times the failure rate of primary ACL reconstruction and is associated with inferior clinical outcomes, including lower Cincinnati, Lysholm, Tegner, IKDC, and KOOS scores [36]. Therefore, patients with unrealistic functional expectations may be unhappy with the final result. In a similar fashion, surgeons should consider carefully any patient that might be unwilling or unable to comply with postoperative rehabilitation or surgical precautions.

Malalignment and concomitant ligamentous injury is a contraindication to revision ACL-R if not corrected prior to, or at the time of surgery. Varus malalignment causes graft strain [37] and potentially graft failure. In addition to coronal malalignment, sagittal malalignment (increased tibial slope) should be taken into account when planning a revision surgery. Unaddressed posterolateral and posteromedial corner injuries also places strain on the ACL graft which can lead to failure [37, 38] as does untreated meniscal injury or meniscal deficiency. Careful attention should be paid to the presence of meniscal root tears when considering a revision ACL-R. Meniscal deficiency in the setting of a failed primary ACL-R may be an indication for meniscal transplantation.

Illustrative Cases

Case 1

The patient is a 26-year-old male who underwent primary left ACL-R with patella tendon autograft. He returned to all activities, including competitive soccer at 9 months after surgery. Fourteen months after surgery, he re-injured his knee in a traumatic fashion playing soccer. Physical examination was consistent with ACL graft tear, which was confirmed by MRI. No meniscal tear or concomitant ligament injury was identified. He had symmetric, passive knee hyperextension. The etiology of graft failure was felt to be recurrent trauma, ligamentous laxity and increased tibial slope. Because of his desire to return to competitive soccer, he elected to proceed with revision ACL surgery. He underwent a single-stage revision ACL-R with contralateral patella tendon autograft and lateral extra-articular tenodesis (modified Lemaire procedure) (see Figs. 3.1 and 3.2).

Case 2

The patient is a 25-year-old female with anterior knee pain and knee instability. She underwent an ACL-R with hamstring graft and partial lateral meniscectomy 8 years prior to presentation. She has had functional instability, including ADLs, since a minor ski injury 1 year ago. Physical examination was consistent with ACL insufficiency, including a high-grade pivot shift. Plain radiographs revealed no arthrosis or malalignment. MRI confirmed a chronic appearing ACL graft tear, lateral meniscus root tear, and vertical and longitudinal tear of the medial meniscus. The etiology of the graft failure was felt to be multifactorial and not related to recurrent trauma. Because of her functional instability, young age, and reparable meniscal tears, revision ACL-R was indicated and she elected to proceed. She underwent revision ACL-R with patella tendon autograft, lateral meniscus root repair, medial meniscus repair, and lateral extra-articular tenodesis (modified Lemaire procedure) (see Fig. 3.3).

References

Gianotti SM, Marshall SW, Hume PA, Bunt L. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury and other knee ligament injuries: a national population-based study. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(6):622–7.

Wright RW, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of the Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS) cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1979–86.

Freedman KB, D'Amato MJ, Nedeff DD, Kaz A, Bach BR Jr. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(1):2–11.

Yunes M, Richmond JC, Engels EA, Pinczewski LA. Patellar versus hamstring tendons in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(3):248–57.

Allen MM, Pareek A, Krych AJ, et al. Are female soccer players at an increased risk of second anterior cruciate ligament injury compared with their athletic peers? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2492–8.

Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, et al. Risk of tearing the intact anterior cruciate ligament in the contralateral knee and rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament graft during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective MOON cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1131–4.

Chen JL, Allen CR, Stephens TE, et al. Differences in mechanisms of failure, intraoperative findings, and surgical characteristics between single- and multiple-revision ACL reconstructions: a MARS cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1571–8.

George MS, Dunn WR, Spindler KP. Current concepts review: revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):2026–37.

Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(2):246–51.

Salmon LJ, Pinczewski LA, Russell VJ, Refshauge K. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon autograft: 5- to 9-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1604–14.

Kaeding CC, Aros B, Pedroza A, et al. Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: predictors of failure from a MOON prospective longitudinal cohort. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):73–81.

Osti L, Buda M, Osti R, Massari L, Maffulli N. Preoperative planning for ACL revision surgery. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25(1):19–29.

Chalmers PN, Mall NA, Moric M, et al. Does ACL reconstruction alter natural history?: a systematic literature review of long-term outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(4):292–300.

Baer GS, Harner CD. Clinical outcomes of allograft versus autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(4):661–81.

Bach BR Jr. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(Suppl 1):14–29.

Borchers JR, Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, Wright RW. Intra-articular findings in primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a comparison of the MOON and MARS study groups. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1889–93.

Johnson DL, Swenson TM, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery: experience from Pittsburgh. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;325:100–9.

Uribe JW, Hechtman KS, Zvijac JE, Tjin ATEW. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery: experience from Miami. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;325:91–9.

Harner CD, Giffin JR, Dunteman RC, Annunziata CC, Friedman MJ. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent instability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:463–74.

Brophy RH, Wright RW, David TS, et al. Association between previous meniscal surgery and the incidence of chondral lesions at revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):808–14.

Argentieri EC, Sturnick DR, DeSarno MJ, et al. Changes to the articular cartilage thickness profile of the tibia following anterior cruciate ligament injury. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(10):1453–60.

Chaudhari AM, Briant PL, Bevill SL, Koo S, Andriacchi TP. Knee kinematics, cartilage morphology, and osteoarthritis after ACL injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(2):215–22.

von Porat A, Roos EM, Roos H. High prevalence of osteoarthritis 14 years after an anterior cruciate ligament tear in male soccer players: a study of radiographic and patient relevant outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(3):269–73.

Gillquist J, Messner K. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and the long-term incidence of gonarthrosis. Sports Med. 1999;27(3):143–56.

Indelicato PA, Bittar ES. A perspective of lesions associated with ACL insufficiency of the knee. A review of 100 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:77–80.

Allen CR, Wong EK, Livesay GA, Sakane M, Fu FH, Woo SL. Importance of the medial meniscus in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(1):109–15.

Osti L, Del Buono A, Maffulli N. Anterior medial meniscal root tears: a novel arthroscopic all inside repair. Transl Med UniSa. 2015;12:41–6.

Meniscal and articular cartilage predictors of clinical outcome after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1671–9.

Kamath GV, Redfern JC, Greis PE, Burks RT. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):199–217.

Zantop T, Schumacher T, Diermann N, Schanz S, Raschke MJ, Petersen W. Anterolateral rotational knee instability: role of posterolateral structures. Winner of the AGA-DonJoy Award 2006. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(9):743–52.

Ohly NE, Murray IR, Keating JF. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: timing of surgery and the incidence of meniscal tears and degenerative change. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(8):1051–4.

Lefevre N, Klouche S, Mirouse G, Herman S, Gerometta A, Bohu Y. Return to sport after primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective comparative study of 552 patients from the FAST cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):34–41.

Battaglia MJ 2nd, Cordasco FA, Hannafin JA, et al. Results of revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2057–66.

Andriolo L, Filardo G, Kon E, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: clinical outcome and evidence for return to sport. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(10):2825–45.

Group M. Predictors of clinical outcome following revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2020;38(6):1191–203.

Wright RW, Gill CS, Chen L, et al. Outcome of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):531–6.

Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD, Hewett TE. High tibial osteotomy and ligament reconstruction for varus angulated anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(3):282–96.

Getelman MH, Friedman MJ. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(3):189–98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sundet, A., Boyd, E., Joyner, P.W., Endres, N.K. (2022). Indications for Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. In: Alaia, M.J., Jones, K.J. (eds) Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96996-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96996-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-96995-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-96996-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)