Abstract

Scrupulous ethical practices should never be side-lined in the fast-paced decision making of crisis management. Indeed, Colley contends these times may well come with more significant ethical elements. Upholding standards whilst accruing value, or at least mitigating damage, may ultimately be the greatest leadership test.

This chapter offers a series of case studies to demonstrate the complexities of ethical practices, particularly when a leader is contending with inadequate information and uncertainty. One involves leading a Western team while conducting business in an institutionally corrupt country. Other real-life examples examine poor senior management behaviour, product recalls when the stakes are high, and boardroom battles. Colley follows his analysis with a theoretical model, guiding leaders in the task of identifying and maintaining an ethical business culture.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

This chapter is entirely case study based, intending to develop your understanding of ethics and values that are fundamental to organisations . Through analysis of practical examples and applied theory, it will invite questions as to how you as a leader might respond to crisis situations in an ethically considered way.

-

Why do ethics and values matter?

-

How can you lead effectively amidst the ethical challenge of globalisation?

-

How can you create an ethical culture in a highly driven environment?

-

What is the nature of ethics and leadership with the hidden culture of ‘white-collar crime’?

-

How can you manage product recalls when the stakes are high?

-

Do ethics have a role amidst boardroom battles?

-

How can you spot an unethical culture?

During times of crisis and turmoil, leaders are often required to make decisions that include a strong ethical component. Such decisions, if handled thoughtfully, can serve to bring stability, humanity, and hopefully profitability to an organisation. If handled badly however, they can cause not only personal regret, but significant damage to the organisation. Some decisions in times of crisis may simply prove wrong however they are viewed, others may have adverse moral and ethical implications that lie with the decision makers themselves. All leaders must be aware that pressure, fear, and uncertainty can act to distort the decision making process.

A topical example can be drawn from the early stages of the UK’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Hospitals assumed that younger COVID-19 sufferers might respond best to intensive treatment using ventilators and breathing assistance. With cases multiplying every day, medics and government elected to free up beds by transferring elderly COVID-19 patients back to care homes. Sadly, the bulk of care home sufferers did not have access to similar treatments, resulting in a disproportionate rate of loss compared with all other demographics.

In a situation where little was still known about the virus, a section of the population was disadvantaged for the greater good in an imposed form of utilitarianism (Driver, 2014). Rightly or wrongly, there were further decisions to be made in the next year regarding restricted visits to elderly care home residents. Undoubtedly the confusion and isolation of these accelerated dementia-related symptoms made for a cruel reminder of how vulnerable we are to the decisions of our leaders.

Despite restrictions intended to limit the means of transmission, death rates in care homes—the most vulnerable and closely quartered sectors of society—were enormous. Moreover, this protracted situation was only declared discriminatory by UK courts a year later. A more rapid implementation of visitor testing, or later still, vaccine passports could have reduced the emotional pain of this situation.

People are by default supreme followers, so it is imperative that our leaders pay serious attention to their ethical conduct. Scholars argue that ethical leadership has always been paramount, yet both research and practice suggest that individuals and organisations find it difficult to exercise. We live in an ever more technologically interconnected world and this wider reach alone makes ethical leadership more critical than ever.

Leadership Ethics: Ongoing Debate

Leadership ethics can be traced back to some of the earliest classical philosophers, including Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle (Ciulla et al., 2018). Many of their core writings were founded on justice, fairness, and democracy, teaching that ethical leadership is an essential tool for building solid and prosperous communities. Being a leader involves power and influence, but also responsibility for individuals, groups, and society as a whole. The capabilities or virtues ascribed to leadership are evidence of a certain set of values, referred to here as ethical or moral.

More recent critiques of ethical leadership in business have focussed on the organisation and interpersonal dynamics between leader and follower. In these theories, humility is also a defining moral virtue that creates trust, commitment, and conscientiousness within an organisation. To be an ethical leader is to empower others to create high trust cultures of organisational excellence (Caldwell et al., 2017).

A perspective that has gained increasing approval in recent years is that of Transformational Leadership that, by way of rigorous research, has established a strong connection between successful leadership and high moral reasoning. These findings led to the development of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire or MLQ (Turner et al., 2002)—a psychological leadership assessment tool (Northouse, 2016, p. 189) valuable in assessing personal leadership style.

Equally relevant to Transformational Leadership are its followers and their aspiration to higher moral standards and levels of functioning. The original concept of Transformational Leadership derives from James McGregor Burns’ theory of 1978 and has since been developed into a new paradigm for leadership theory. Its basis is not so much on leader–follower transactions, but on the motivation and morality the leaders provide to those surrounding them. Ultimately this means Transformational Leadership is most applicable to an organisation’s long-term goal (Northouse, 2016, pp. 161–62).

Collins’ (2016) concept of level 5 leaders applied to those that combine professional excellence with humility; these are the leaders most capable of taking their company ‘from good to great’. The values ascribed to level 5 leaders fit into the concept of Transformational Leadership (Caldwell et al., 2017), but also share similarities with the theory of Servant Leadership in which humble leaders adopt the role of servant in order to understand their own strengths and weaknesses.

All theories have their limitations, however. Although they create paradigms for leader conduct, they often fail to differentiate whom its benefits are aimed towards, whilst the Transactional Leader acts alone and the Transformational Leader for the sake of their organisation, the Servant Leader is intended to be entirely altruistic and not necessarily profitable; in short, none make for a balanced pragmatic approach within an organisation.

We know that no matter the values espoused, there comes a point at which policies meet pragmatism and leaders face the difficult negotiation of upholding ethical standards whilst under pressure to generate economic value. Compromises are bound to ensure, and, in this case study, we investigate the difficulties which surround such decisions. Timely responsiveness nearly always calls for distributed leadership, trust, and development (Bolden, 2011) to avoid sub-optimal decision making. The relationship between organisations, teams, and leaders has never been more important than when dealing with decisions with a significant ethical component.

The Case Studies to Follow

The format of this book is to present you with narrative case studies of commonly encountered situations. These are followed by questions that ask you to reflect on your own leadership practise in regard to ethical conduct. We consider the work of Epley and Kumar (2019) in relation to developing an ethical culture and what actions a leader needs to take to reach that end. How often are a business’s actions at major variance with the espoused statement of ethics emanating from boards? How can a business drive those values into their culture such that they become the norm? Does the board ‘walk the talk’ and ‘practice what they preach’? These will be among the questions addressed.

-

In ‘The Russian Way’ we consider how a leader might encounter local opposition to the construction of new plants overseas. We refer to the pitfalls of such investments and how knowledge of antecedent corruption may prevent potentially damaging business decisions.

-

‘A Poison Pen Letter’ addresses the role of the whistle blower, what issues commonly arise by whistle blowers and the difficult decisions that must be made regarding source credibility and what accusations may expose about an organisations ethical culture.

-

People working in organisations are likely to be familiar with ‘white-collar crime’ such as bullying, sexual harassment, bribery, and dubious accounting to name a few. This is often a ‘submerged’ culture—its activities may rarely travel up an organisation but can be only too apparent to those working amongst it. We discuss solutions to this in the context of Healy & Serafeim’s, 2019 work, with guidance as to how leaders identify white-collar crime. Reference is made to the 1995 case regarding the BBC journalist Martin Bashir’s interview with Princess Diana using forged documents and what measures should be taken to protect potentially vulnerable individuals and sensitive information.

-

‘Uber’ enables us to look in detail at how values have suffered in environments where technological development has gone hand in hand with associated business growth. Uber exhibited signs of subjugating standards in pursuit of growth targets which led, as of 2021, to a business worth in excess of $100 bn, despite previously being accused of disregarding rules and laws. Prior to this unprecedented growth, the organisation was accused of unethical conduct. We will study Uber’s dominant market position, alongside major efforts to improve values and ethical culture in recent years.

-

A shorter case study reviews the potential damage to reputation and internal organisation dynamics as a result of faulty products and the need for their recall. This is a chance to reflect on how a leader responds even when they know the fault to be correctable and localised.

-

Finally, we consider the politics of the board room and how discord amongst higher management easily percolates down, impacting an organisation’s overall success and ethical culture.

In considering these cultures, leaders must remember how the consequences of poor ethical behaviour are now more broadly accessible. The easy deployment of social media means chances of suppressing knowledge of unethical decisions are significantly reduced. As a result, the importance of clear ethical statements and consistent actions has never been more important.

Reflection

-

Have you ever had to deal with issues in which ethics and values were a significant component?

-

How did you take measures to address the issue?

Case Study: The Russian Way—Little Is What It Seems

Construction was going well on a new Russian brick production plant sited a few hundred miles to the west of Moscow. The £100 M scheme was progressing after an arduous delay in obtaining the permits needed to buy land and build the plant. This was the first foray into Russia for the multinational business and progress had definitely been slow. Globally the product was penetrating markets rapidly and the business had now built plants in more than 30 different countries around the world. Russia had been selected for the next plant as the economy was accelerating rapidly and Western businesses appeared to be welcome. Despite a reputation for corruption following the Yeltsin era, significant progress was being made with regard to cleaning up the approach to business and the backing of the Regional Governor had been the necessary accelerant. The scheme would create several hundred well-paid jobs in an area of relatively high unemployment; it would inject much needed cash into the regional economy. However, the multinational’s International Director was aware that this may be met with some challenge.

Foundations were in place and the plant was rising from the barren wasteland on which it was being built when the local Regional Governor was promoted to a higher position in central Moscow and a new one appointed.

Some months later disturbances began when local boar huntsman claimed that their traditional hunting grounds were disappearing as a consequence of the scheme. This was a cultural issue previously unknown to Western management, and that now rapidly started to gain more traction and news coverage. Attempts were made to contact the huntsman community to discuss their concerns but with little success; they simply did not wish to engage.

As the campaign gathered support, the local governing body made a decision to retract all permits and prevent the scheme progressing. This was something of a disaster for the International Director after such a sizeable investment had been made and that now looked to be in severe jeopardy. A meeting was hastily convened with the new local Governor.

The International Director laid out the situation to the Governor and explained that he could not understand why these objections had arisen at such a late stage and permits so categorically withdrawn. The Governor sympathised with his predicament but said there was little he could do in the face of such strongly opposed public opinion.

As the International Director was about to leave following this fruitless discussion, the Governor suggested, ‘had you thought of a local public relations campaign to persuade hearts and minds that this scheme is in everyone’s best interests?’ The Director responded that this had already been tried with various local PR businesses and had even garnered some positive TV, radio, and newspaper coverage, but that little had been achieved. The Governor thought for a minute before producing a card: ‘Try this firm. I have heard they are very good at resolving this type of issue’.

Reflection

-

What should the International Director do?

-

What would you do in the circumstances?

Discussion

Transparency International (Transparency.org/cpi) is an independent organisation which attempts to expose the scale of worldwide corruption in the public sector. They define corruption as ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain’. In their words, corruption ‘erodes trust, weakens democracy, hampers economic development, and further exacerbates inequality, poverty, social division, and the environmental crises’.

A corruption league table of 180 countries is published annually (Corruption Perceptions Index) together with an explanation of the extensive methodology and the key issues which businesses may face in each country. The top ten ‘clean’ countries usually include the four Nordic countries together with New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. However, once a country falls out of the top 50 it can be assumed that corruption is largely endemic; India, China, Russia, together with many Eastern European and Balkan countries are included in this category. A business setting up or running operations will have to manage corruption in some form, directly or through agents such as lawyers, public relations firms, or venture partners.

Although largely shrouded in darkness at the main board level, corruption is the major issue in need of management for Western-based corporations entering international markets. Boards are often well aware of potential cultural challenges, but seldom the sheer scale of them.

Public sector corruption is illegal in most countries (Fleming et al., 2020); however, the degree of enforcement varies enormously. In corrupt countries, the exposure of corruption usually involves score settling or deposing of a rival. It is a highly selective means of maintaining political control or power, whilst a significant number of politicians may actually be involved in unchallenged corruption.

In some Western countries, independent authorities will investigate whistle blower testimonies; in fact, a significant number of corporations—Walmart, Airbus, Goldman Sachs, Siemens, BAE Systems, Alcatel-Lucent, and Rolls Royce, to name a few—have suffered major fines for industrial scale bribery in international markets.

However, this underestimates the scale of the problem and exposes only some major corruption cases. Corruption is often endemic as illustrated in the example.

Western corporations are placed in a difficult position since, if they wish to internationalise beyond a limited list of countries, then they have little choice but to manage corruption one way or another. This is usually through intermediaries to blur the audit trail and attempt to create distance. There still remain major ethical issues to consider. Corporations often claim to be ‘clean’ through their public relations but what other choice do they really have?

There are also discussions about the arrogance of Western nations inflicting their moral values upon other countries. A counter argument is that the local laws usually make corruption illegal. Ultimately, it is the people who suffer. They see their taxes being stolen, which encourages behaviour towards evading tax. Ultimately public services cannot then be adequately funded and the quality of life for all deteriorates.

Leadership does embrace making difficult decisions and applying judgment (Shotter & Tsoukas, 2014). If Western corporations choose not to enter many transition economy countries due to the extent of corruption, this will hinder country development and reduce the opportunity to fight corruption. Many countries are so corrupt that they suffer this fate. However, there are others which may ultimately be redeemable, which makes the leader’s task still harder. They face the difficult question of how to flourish in a country without experiencing the ill-effects of corruption.

Reflection

-

Is your business active in countries which have low transparency ratings?

-

Do you know how values are managed in those territories?

Why Do Ethics and Values Matter?

A ‘Poison Pen’ Letter

Tucked in amongst the post was a handwritten letter on personal writing paper, post marked from Perth. To Adam, recently appointed as CEO of a large service business, it looked like a poison pen letter, always interesting but not necessarily accurate. The letter had been handwritten in capitals as an attempt to disguise the identity of the writer and with its various spelling errors certainly looked authentic.

The letter detailed the behaviour of the local Area Manager’s Personal Assistant, apparently a force to be reckoned with in the regional business. The writer claimed that people who crossed her, particularly in administration, usually ended up losing their jobs. Several instances were specified in some detail. There was a suggestion that on occasions she did bully people and as a consequence appeared to wield an authority which went well beyond the powers of an Area Manager’s Personal Assistant.

The further allegation was that she was conducting an affair with the companies’ Operations Director who sat on the board. The Operations Director in question was married and had previously been Area Manager in South West Australia. During the last year, he had been promoted to his current role and his deputy promoted to manage the area. The area was sizeable and employed around 500 employees. The letter alleged that the Personal Assistant’s power was a consequence of her ongoing relationship with the Operations Director.

The business had previously experienced a difficult period in regard to operations directors. Around three years previously, the then Operations Director had retired, and he had been replaced with an external recruit. Despite major efforts to embrace the culture and introduce modern management methods, overall performance had deteriorated substantially, and the external hire was eventually released. The new internal appointment was previously the South West Area Manager who understood the culture and was now starting to restore better levels of performance throughout the business. He still lived in the Perth area with his family, despite the company’s head office being in the east.

Adam called in the HR Director and showed him the letter. The HR Director, Mike, had been with the business many years in a variety of roles before being promoted to his current position. ‘Is this true?’ asked Adam. ‘It may well be’ replied Mike. Adam sensed that Mike knew far more about this than he cared to admit. ‘I will make some discrete enquiries and get back to you’, responded Mike. ‘By the way’ asked Adam, ‘Do we have a policy on relationships between staff, particularly where there is a line of management?’ As the Kent Area Manager reported to the Operations Director and the Personal Assistant reported to the Area Manager, it meant there was a direct line of power influence. ‘I’m afraid not’, responded Mike. ‘I think we are going to need one, Mike’, retorted Adam.

Adam reflected that there seemed to be a force field around him which prevented bad news from being received. Good news seemed to arrive rapidly, whilst matters he should have known failed to make it into his office. Clearly, if the letter was true, then the South West Area Manager was in a difficult position as his boss was having an affair with his assistant, which was probably undermining his position. But would that really explain why the assistant was able to wield such power?

A week later Mike returned and explained that the letter was largely correct or so it seemed. He had made enquiries through a number of employees he knew well at the area and they largely substantiated the allegations. However, he felt that it was unlikely that anyone would offer formal evidence, on the grounds that should there be an absence of managerial action then there could be reprisals.

Adam’s thoughts were that clearly this situation could not be allowed to persist and action was needed. What should Adam do in view of the circumstances?

Discussion

The illustrative case identifies several key problem areas when dealing with decisions which have a significant values element. For senior managers, this may amount to a substantial proportion of their decision making. Clearly the instigator of the letter is concerned that their identity may become known and that there could be reprisals, hence anonymity. This may also signify a lack of confidence in management to effectively resolve the situation. ‘Whistle blowers’ are rarely treated well (see below). Secondly there is a concern to ‘right a wrong’. Of course, this might be a score settling exercise too.

Breaking down this example further, the business does not have a policy so whatever it does might be subject to some form of legal challenge. Perhaps it goes without saying that running a business does involve some risk and there is always a temptation to do nothing, which effectively maintains the status quo. However, is that really feasible in this case? We also know that the current situation places the Area Manager in a difficult situation as his assistant appears to be having an affair with his direct boss, which undermines him. We also know that the assistant appears to be unfairly using the relationship to develop power, which she may be abusing. There will also be resentment and jealousy amongst staff that the personal assistant may be receiving other advantages from her relationship.

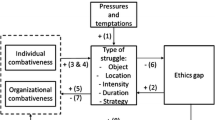

There is also the question of the real evidence. The letter is anonymous although the HR Director, who has an excellent network which he has tapped, is suggesting that the letter appears to be accurate in its claims. However, it is unlikely anyone would want to formalise his or her evidence or stand by it. If there were to be no effective action then, they would have exposed themselves to retribution from conceivably both the assistant and Operations Director. A summary of some of the difficulties to be considered in such cases (see Fig. 4.1):

-

Issues are often ambiguous, complex and lacking in information.

-

Even with a policy in place, there still remain difficulties in collecting adequate evidence to act. People may offer information but only ‘off the record’. Formal processes often ensure fairness and legitimacy but fail to resolve the continuing issues. Those supplying information have the concern that grudges may persist post the investigation.

-

There is often no right answer or easy solution and whatever decision is made could well have some adverse consequences. This may result in, either victims who do not feel justice has been done, or the accused perceiving they have suffered injustice; claims and litigation may ensue.

-

There are frequently issues about balancing economic value to the business versus upholding decent ethics standards. The cost of good values can be economically substantial.

-

Of primary consideration are the victims, current, and, unless the situation is resolved, future. This means that doing nothing is not a realistic option.

-

Resolution of difficult issues such as this requires decisive action and imagination. It is important that values are seen to be upheld and the solution viewed as fair. Ideally it should be difficult to legally challenge, although any decisive action often carries that risk.

Even if there were a policy in place, the business would not wish to lose the Operations Director, particularly given he had turned around the poorly performing operations activities. As the costs and risk in trying to find another, equally effective Operations Director are significant, what should Adam do? (Fig. 4.1).

There are greater issues here, outlined by Epley and Kumar in their 2019 article for the Harvard Business Review, ‘How to Design an Ethical Organization’ (2020). Firstly, many organisations have clear statements of high morals on paper. However, it is actions and incentives that link these statements and policies to an ethical culture. If those actions of senior management are not consistent and fail to uphold the principles, then, for all expressed purposes, those principles are not being implemented.

Similarly, incentives mean consequences. If there are no consequences for behaviour which fails to meet the organisation’s standards, then it will continue and proliferate. These situations are often seen by managers as too difficult or time consuming to address. They are also likely to be unpleasant and messy. Managers have to take a view as to whether their superiors will really support them in any sort of action, and they often do not. The likely consequence is that it is easier to do nothing or simply speak to the parties concerned but take no further action, allowing the situation to persist. Responses to these kinds of situations define the culture and ethics of an organisation.

Whistle Blowers

‘Whistle blower’ is a term typically used to describe an employee who exposes information about activities which may be illegal, fraudulent, unsafe, abuse of public money, or bullying (Fotaki, 2020).

Whistle blowers can be categorised by public and private organisations, and internal and external. Externally is usually to media, or law enforcement. Internally may be to senior management. Public institution allegations often concern public money misspending or abuse of position.

What we do know is that whistle blowers are almost universally badly treated by their organisations. External leakage of information usually involves termination of contract. Organisations are concerned about their image and carefully manage the flow of information to media or external bodies. Termination sends a message to others regarding whistle-blowing activities.

Many countries have laws to protect whistle blowers, however their effectiveness is questionable. Those who are not fired may suffer internal action to make their lives less comfortable such as a major increase in workload. Organisations are often required to have internal complaints systems to provide anonymity, however employees may have limited confidence in such systems.

In 1995 the BBC journalist Martin Bashir procured an interview with Princess Diana using forged documents. Princess Diana was viewed by many as a ‘vulnerable’ person. The subsequent interview resulted in Princess Diana losing royal support which ultimately ended in divorce and the loss of her royal title. A subsequent investigation by long-term BBC director Lord Hall determined that Bashir did not have a case to answer and that no wrong doing had occurred. Various whistle blowers were fired as a consequence of leaking material to the media. A recent investigation by Lord Dyson determined that the allegations were correct and that the interview was procured using fraudulent means. A question put to the BBC by a journalist was why had no one been sacked by the BBC as a consequence of the affair other than whistle blowers?

Reflection

-

Have you had to deal with difficult staff issues?

-

To what extent did you find policies helpful in resolving the issues?

White-Collar Crime

One can argue that all companies suffer from some white-collar crime. It can take a number of forms, including the following.

-

Conflicts of Interest

-

Sexual harassment and bullying

-

Bribes or inappropriate gifts

-

Accounting irregularities

-

Antitrust violations

-

Theft

The extent and depth largely come down to the nature of the culture which, more often than not, takes its lead from the actions of top management. Such white-collar crime can bring about significant trust and reputational damage as well as cost billions of pounds. In the case of the major UK clearing banks, they have paid several tens of billions in compensation to customers who have been mis-sold inappropriate products. An example of such a product is loss of employment insurance which has been structured so that there are few circumstances in which it will pay out. The bank’s current share prices are less than half the level before the various scandals were identified. The main drivers were sales bonuses for selling the products and an unwillingness to challenge the morality of the products. In effect, the four banks saw each other making money from these products and felt they could benefit from entering these dubious markets.

Healy and Serafeim (2019) have identified that the main driver of such crimes is weak leadership and a culture of making the numbers at all costs with a blind eye turned to dubious practices. Their solution is that leaders need to broadcast to all their employees that crime does not pay. They must punish perpetrators equally, and hire managers known for their integrity. Some industries, such as waste disposal, have a reputation for dubious practices or anti-trust activities (common to many industries). In these circumstances recruiting from outside the industry may be necessary. They must also create decision making processes which reduce the opportunity for illegal or unethical acts, and champion transparency. Involving the entire team in decision making helps reduce the propensity for unethical decisions, particularly when the leadership is clear on what is not acceptable.

Reflection

-

How often does bullying and harassment occur in an organisation without being reported or acted upon?

-

How does your own organisation perform in relation to ‘white-collar crime’?

What are Business Ethics?

Business ethics are moral principles that guide the way a business behaves. These include norms, values, unethical and ethical practices which guide the business. It is distinguishing between what is morally right and wrong when selecting courses of action that are often complex. This frequently involves the interaction of profit maximising behaviour with non-economic concerns and the impact on other stakeholders.

Ethics is concerned with the study of morality […] and the elucidation of rules and principles that result in morally acceptable courses of action. Ethical theories are the codifications of these principles. (Crane et al., 2019)

Businesses often have ethics codes and social responsibility charters to provide guidance to employees. These are intended to regulate behaviour in areas of concern which go beyond what is covered in government regulation and the law, but which may be viewed as unacceptable to the business and its stakeholders.

Many of the questions we face are equivocal in that there may not be a definitive ‘right’ answer. Choosing between different courses of action may involve a complex consideration of many different ethical aspects and widely varying points of view.

Some of the most prominent ethical issues encountered include:

-

Employment and comparable worth (Amazon and low pay, zero hours contracts)

-

Discrimination (age, race, gender, disability)

-

Workplace safety

-

Marketing ethics (inappropriate product/service claims—mis-selling, distortion of perceptions)

-

‘Greenwashing’

-

‘Pyramid selling’

-

Consumer fraud

-

Corruption

-

Misuse of business resources (executive pay and allegations against Carlos Ghosn of Renault)

-

Child labour, slavery, exploitation

-

Environmental destruction (BP)

-

Tax avoidance

-

Sustainability and climate change

Shareholder, Stakeholder, and Stewardship Theories

The following theories are useful in analysing motives and rationale behind events.

Shareholder theory is the view that the only duty of a corporation is to maximise profits accruing to shareholders. Other stakeholders are satisfied only to the extent of safeguarding shareholder returns. So poor reputation could restrict sales and reduce shareholder returns. Similarly relations and management of customers, employees, suppliers, government, and environmental concerns are with the objective of preventing damage to shareholder returns. In terms of legal activities it could be argued that the business only complies with the law to the point that conceivable consequences of breaching regulation are worse than the profits made from such breaches.

Stakeholder theory considers the business from the perspective of creating value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders. In effect there are multiple constituencies who have a legitimate interest in the corporation. This includes the environment which does not have a voice. The theory assumes two principles:

-

That of corporate rights which demand the corporation does not violate the rights of others.

-

That of corporate effect that the corporation is responsible for the effects of their actions on others.

Hence businesses have a responsibility to create employment and pay fair wages. They have strong environmental credentials which go beyond reputational damage. Sourcing would be ethical despite increased costs even though this may not be a potential source of competitive advantage through reputational improvement (such as in the case of B2B).

Stewardship theory is the view that ownership does not really own a business but looks after the business on behalf of all constituencies. There is a higher vision or purpose beyond shareholder satisfaction. The theory assumes that managers left on their own will act as responsible stewards of assets on behalf of the owners. In a choice between self-serving and pro-organisational behaviour people will choose the latter. They are trustworthy collectivists who have a belief in a higher vision.

However the CEOs operate the business on behalf of the owners or intended beneficiaries (e.g. charities). This tends to contrast with agency theory which considers that the owners and managers of the business pursue their own interests and objectives, which necessarily diverge. In effect this model assumes a high level of trust unlike the agency model which believes that objectives diverge where there is the passage of limited information on the business performance.

Case Study: Uber and Kalanick—Always Hustling!

Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick had one thing in common—they disdained and were frustrated by the US city approach to taxis. The ‘medallion system’ adopted by many cities was designed to ensure drivers were reasonably remunerated through metered rates and that they had been subject to certain checks and were registered. However, the system created taxi shortages and the meter system ensured that passengers had no idea what the journey would cost until it was complete. It also made trips expensive. So not only were taxis in short supply at rush hour but passengers had to put up with expensive fares of indeterminate amount, plus demands for cash payment and a sizeable tip. Drivers safe in the knowledge that they had a job for life and decent remuneration could be discourteous. In one form or another, similar systems were in operation in many cities around the world. The passengers were receiving a poor deal and the system was loaded in favour of the drivers.

Camp and Kalanick devised the genius idea of a ride hailing app which might, on occasions, ignore regulations but provide a far better deal for travellers. They would provide a quote through the Uber app and give an estimate of when the taxi would arrive. There would be no tip to pay, and all transactions would be by pre-registered credit card. A mutual assessment system would be in operation so that passengers could assess the courtesy level of the driver and vice versa. Hence future drivers and passengers could identify lower ratings in advance before entering into the transaction. In addition, Uber, the app provider, would simply link drivers to passengers and take commission on the deal. They would set the rates and collect payment from the passengers and pay the drivers after deducting their commission. Uber believed that they were merely providing a platform that connected travellers to drivers, and were therefore not responsible for the various parties involved in the transaction.

They were also aware that, in this market, being first was critical, as was creating network effects as a barrier to followers. So the more passengers Uber could attract the more drivers would want to sign up wanting to earn more. The more responsive the service became through having more drivers, the more travellers would wish to use it. Each would drive what are two-sided network effects. Once created, this provided a major barrier to potential followers wishing to copy the approach. Rates were a fraction of those offered by metered taxis.

Camp and Kalanick knew they would have to pump prime the model by offering incentives to drivers and passengers to build scale rapidly. They also anticipated challenges from the authorities as they may have disregarded regulation and operated on the edge of legality. Indeed, regulation said little about ride hailing platforms and so they operated in a legal grey area. They would meet authority challenge by growing the service rapidly so that, if eventually banned, large numbers of drivers would lose their jobs, and customers would lose cheap and convenient travel. Customers and drivers are voters in local government elections. Uber would invest heavily in public relations and lobbying local government and authorities. The objective was to make it as difficult as possible for politically sensitive local politicians to oppose them.

Funding the Venture

Travis Kalanick had made money from a previous venture (‘Red Swoosh)’, but had been fired by venture capital investors as they sought to accelerate development of the enterprise. As Travis famously said, ‘It is in the Venture Capitalists (VC) nature to kill a founding CEO. It just is’. Following the success of Facebook, Google, and Amazon, Kalanick was not going to offer VC that opportunity again. VCs were desperate to invest in technology start-ups. So Kalanick introduced two classes of share: founder shares with most of the votes and VC shares which had little in the way of voting rights. Cheap money, booming device ownership around the world, and the ability to develop software infrastructure rapidly using Amazon Web Services generated significant opportunities. So in 2009, Uber Technologies came into being and headquartered in San Francisco. In total it raised over $25 bn to fund the global development of Uber taxis plus a variety of other ventures, including takeaway food delivery, freight services, bikes, and autonomous vehicle development.

By 2019 Uber claimed 78 M users, a 67% market share in the USA and revenue (commissions) of $14.1 bn. Its operating income was a loss of $8.6 bn. Indeed, with COVID-19, results for 2020 looked likely to produce losses at a similar level. However, despite Uber having a consistent history of major cash losses each year, the stock market valuation at the end of 2020 still stood at $94 bn.

Ethics and Values in a Driven Culture

Kalanick was famously driven and believed in ‘always hustling’, in short, pushing at the regulatory limits wherever beneficial. His view was that achieving targets for revenue and user growth were prime means by which investors valued the business. He appeared less concerned with how his teams achieved the targets or the nature of the high-spirited culture. The pace of Uber’s growth was staggering as driven and highly remunerated teams were set up in major cities throughout Europe, India, Southeast Asia, and China. The goal of these teams was to generate growth. Money was little object as venture capital money was so easy to come by. As each growth target was achieved, Kalanick would organise a party for staff. The famous ‘X to the X’ party after achieving sales of $1 bn was believed to cost some $25M. Kalanick rapidly acquired business guru status, producing and presenting his own philosophy of business, as had many Silicon Valley founders. Tellingly, his philosophy did not mention values or ethics. He surrounded himself with similar thinking people who believed that regulation merely presented a business opportunity. However, challenges started to mount up, including:

-

Increased traffic congestion as the business boomed. When Uber entered the London market in 2012, total taxi drivers increased from 65,000 to 120,000 in 2017, and Uber rapidly developed a claimed 3.5 M customers and 45,000 drivers. Previously most customers might have used public transport, bikes, or walked.

-

Safety concerns developed as allegations of sexual molestation amongst drivers mounted. Indeed, in a one-year period in London there were 26 complaints of Uber drivers’ sexual offences against passengers. There were also criticisms that Uber had not reported these allegations and failed to cooperate with investigations.

-

Once the initial driver incentives were withdrawn by Uber, drivers became concerned that they should have employee benefits rather than be treated as contractors on a trip basis. Legal challenges were issued in many territories.

-

Google commenced major litigation that Uber had stolen their ‘Waymo’ autonomous vehicle technology by recruiting a senior staff member.

-

An Uber autonomous vehicle struck and killed a pedestrian whilst being tested, and the supervising engineer was accused of watching videos at the time.

-

‘Greyball’ software was alleged to be used which denied traffic inspectors and government official’s rides by presenting an alternative, limited picture of Uber taxi availability.

-

Employees claimed that a toxic culture existed in which sexual harassment was commonplace. Following an internal investigation, 20 employees were fired in 2017.

-

There were two occasions of major data breaches being disclosed. The second in 2017 disclosed personal data of 600,000 drivers and 57 M customers.

Despite this saga, Kalanick was proving difficult to move from his position. The board was largely powerless as non-founder shareholders had little voting power. Whilst venture capital investors (VC) were represented on the board, some of the Non-Executive Directors were colleagues of Kalanick. What was increasingly apparent was that an initial public offering on the stock market would not be possible unless values improved, and Kalanick was gone. In effect cashing out would not be available for investors including Kalanick and Camp unless there was major change. After negotiating his exit, Kalanick resigned and left the board with several billion dollars and Dara Khosrhowshahi became CEO. He had many issues to resolve with proliferating litigation claims and regulatory authorities to deal with. Uber also needed to make money at some stage.

Discussion

Mike Isaac in his 2019 book Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber described the story as ‘a tale of hubris and excess set against a technological revolution … a young leader surrounded by “yes men” and acolytes given nearly unlimited financial resources and operating without serious ethical or legal oversight’.

Despite the level of losses Uber was still valued at around $94 bn at the end of 2020. Despite the dubious values and suggestions of a toxic culture the founders and venture capital investors have been well rewarded.

Upper Echelons Theory proposes that a business’s values are largely a consequence of the behaviour of the top management team. In turn, that behaviour is a product of their previous experiences. Certainly, in the case of Uber we can conclude that behaviour of management took its lead from the top team. Uber has not been in existence long so there has no previous culture that could have served to moderate behaviour. Instead, the swashbuckling attitude to rules, regulation, and other staff left much to be desired. Indeed, the major celebration parties had been deliberately marketed as an opportunity for excess behaviour.

There has been a cost to Uber, both at the time and subsequently, due to costly litigation and a loss of trust. Transport for London has now twice banned Uber from having a license to operate. On both occasions, Uber have successfully appealed the decision but are now granted short-term licences and have to comply with ever more demanding regulation. Regulation relating to labour practices is tightening and Uber is seen as an early target for legal action due to their historic responses, which are unlikely to attract judicial sympathy.

In the USA, Lyft was able to develop a more significant position as a consequence of Uber’s adverse publicity. Outside the USA, Uber has major competition in every market and there is some doubt whether they will ever make money outside the USA.

Travis Kalanick was handsomely paid off, but his reputation is damaged, and it is likely he would still rather be running Uber. He certainly did not leave without a fight. However, the financial markets have rapidly forgotten the many dubious actions and remain willing to invest significantly in a business they believe will eventually be highly profitable.

Uber had a board with NEDs which ultimately failed to create good ethical standards. They may well have had policies and statements but these need to be connected to behaviour through specific actions and incentives. In reality, the investors were faced with being unable to list unless they resolved the ethics problem. Governance arrangements may be satisfactory on paper, but without clear links to incentives and actions, they are ineffective. In this case, founder shares presented a major barrier to any sort of action in terms of building an ethical workplace and ethical culture.

Reflections

-

In view of the outcome to what extent does ethics and governance really matter?

-

Whilst a governance structure existed, why was it ineffective?

-

Is a driven high-spirited culture, pushing at the boundaries of regulation, bound to fall foul of accepted standards of ethics?

-

What does this case say about governance, ethics, and leadership?

Building an Ethical Culture

Culture emanates from the top team although cultures can be very resistant to manipulation particularly in businesses with long histories. Changing attitudes require high levels of communication and publicising the good things that employees do. The business should present clear rationales for decisions, in particular where some stakeholder groups are disadvantaged or have to bear the brunt of necessary measures for example redundancies or closures. These need to go beyond just saving money.

This means creating an environment that enables people to do the right thing and reminds them that wrongdoing is not allowed. As a leader, your job is to make it known that doing things the right way is necessary.

A problem leaders face is ensuring that they are not holding their followers back in exhibiting ethical behaviour. Ideally, leaders want their employees to come forward and feel comfortable voicing any concerns regarding perceived unethical behaviour. As leaders, we have to make an effort to nurture a work culture in which they feel comfortable in doing so. Unsurprisingly, it is upper management and leadership that most frequently breach ethics (Downe et al., 2016), and the probability of a leader disregarding ethics increases with seniority. As a leader, your most important job is to make sure that you establish your own personal moral code and make sure that your practices and policies follow that moral code. Then you need to build your team around people that can be relied on to follow that moral code and provide support in creating an ethical workplace.

An important element in creating an ethical climate is to frequently raise the issue of ethics. The more leaders emphasise positive behaviours, the more willingly people will follow. Leaders need time to determine their workplace values and create the ethical code that they want people to follow.

Be Careful of Ethical Hazard Zones

Sometimes good people can be caught up in unethical behaviour known as ethical hazard zones (Messick & Bazerman, 2001). Watch out for its most common features (Fig. 4.2):

-

Contradictory Targets

Ethical standards can start to deteriorate when people have to meet performance goals at all costs.

-

Evasion

When unethical behaviour is overlooked, it can incentivise others to act in a similar way.

-

Declining Standards

Once someone has committed an unethical action and avoided the consequences, more become conceivable and so standards decline.

How to Spot an Unethical Culture

By way of summary, it is worth summarising some of the views of Marianne Jennings in her 2006 book Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse. She identifies several symptoms of an unethical culture, including significant pressure to make the numbers, a larger-than-life CEO, fear, and silence internally, and a weak board, usually selected by the CEO. Other symptoms include using charitable activities as a cover for an unethical culture, imaginative accounting approaches, and conflicts of interest at senior leadership levels. If an organisation exhibits several of these symptoms, then it may well be sick. Ultimately, organisations are likely to pay the price for poor ethics one way or another (Fig. 4.3).

Product Recalls

A problem experienced by manufacturers and increasingly service providers is the issue of faulty products and services which have to be remedied. In the service field, there has been the mis-selling of various financial products and insurances which are of poor value, or entirely inappropriate to the client’s needs. UK authorities have subsequently offered retrospective protection and compensation to consumers of complex financial products which few understand, including those that sell them. This has cost the banks some tens of billion pounds in compensation.

Recently recalls have become more frequent. Manufacturers attempt to do this quietly to prevent bad publicity. However, this may now be expedited by government departments who mandate the manufacturer to identify all owners and require action. Car manufacturers can be slow moving due to the expense of a recall and the perceived reputational damage.

However, reputations can be enhanced if there is a rapid and decisive response. This can be used to send a clear message about values and a supplier who is responsible and cares. This is more likely in the retail industry in which supermarket chains demand suppliers stock cleanse all product on the shelves and in stock at their own expense, and fund a returns scheme for all product sold. In these circumstances, the costs are largely identifiable and there is a ‘policeman’ in the supermarkets ensuring rapid action.

Case Study: The Blame Game

Imagine that you manage a building materials business in the Netherlands, and you are informed internally that a manufacturing process has been defective for nine months and that substandard materials are now in 5000 properties across the country. Worse still, it may not be possible to trace all the buildings as the materials pass through distributors. If there were to be a fire it is possible that those materials may not perform to tested standards. The costs of removing and replacing would far exceed your levels of insurance, to the extent that the business would almost certainly become insolvent. However, if fires were to occur, then there should be other fire prevention precautions in buildings specified in building regulation. The chances of the products in question being identified and subsequently tested are unlikely except in the case of a major fire.

We assume that in all circumstances the plant problem is immediately fixed and the plant stood down until the issue was resolved. Secondly, we also assume that a reliable testing regime is introduced across all products to prevent any future recurrence.

Reflections

-

How would you respond to the discovery of faulty manufacturing, regardless of how minor?

-

How might you manage social media and act in a socially responsible and ethically transparent way?

Discussion

This is a difficult situation, the temptation being to fix the problem and then say nothing. However a key issue has to be the risk to life of the product fault. If that is increased then there is little choice but to come clean and admit the problem. In such circumstances the government may pick up funding if it is evident that the business is not capable of carrying the burden.

The chances of the problem becoming known may be unlikely as even if there were a fire, then it would require a number of different fire safety precautions to fail. However, despite the unlikely prospect, a full risk assessment should be undertaken to identify where the real and significant risk exists. To what extent does the product failure increase the overall fire risk? Is it significant? For example, hospitals, schools, and care homes followed by multi-storey buildings should be risk assessed. This review should be undertaken in conjunction with the insurers and the relevant government agencies.

Board Games: Do Ethics Really Matter?

The two brothers sat behind the desk on the Zoom call saying little. When they spoke, it was usually to issue orders or some form of ultimatum. They were clearly used to being obeyed and instructing whilst discussion seemed rather alien to their approach. Their family business, Dresden, had been successful and was now listed on a local stock market. The father had been the driving force in building the business and had now retired taking a back seat to his two sons. In recent years, Dresden had developed beyond Germany into the Netherlands and Belgium, with various minority interests in Denmark.

Between these two brothers, the one with the beard spoke to outline the terms that they were willing to offer for investing in the Austrian business Proteus. ‘We will offer a bullet loan of $5.0Mn repayable in 2 years, plus 60 days trade credit on raw material supplies from our plants. The equity will be $3.0 Mn and management will have control at 51%. You will need to find the pro rata portion from your own funds’.

As chairman of the business, he certainly did not sound like the brothers were negotiating, more akin to a statement. I asked if we could have a few days to discuss amongst ourselves as we had to find over $1.5 Mn between the three of us. He responded, ‘You have 2 days’. It was by far the best offer we had received but working with these two looked to be a real challenge as there was no real scope for a relationship and the COVID-inspired Zoom calls did not help in resolving this!

COVID had resulted in Proteus falling into difficulties as sales had collapsed and the business was already heavily indebted. It needed a major reorganisation to reduce the number of plants and cut overheads which would cost several million pounds in reorganisation costs. We needed a partner to provide the funding and Dresden’s offer would provide $12 Mn in total, which would allow for a much lower cost base and help see us out the COVID epidemic. Private Equity had been approached but their offers were significantly inferior to this, which at least granted us, the management, control. Clearly, we had little choice but to accept.

Challenges Emerge

Around three weeks after the deal was signed and the major reorganisation commenced, we received a call from a board director at Dresden. They wished to merge Proteus into a similarly sized independent Austrian competitor, MF, to which they had been talking. This seemed a strange and certainly unexpected request. ‘So, what do we get?’ I enquired. ‘We will give you shares in the new larger business but sadly we will not need you to manage the business’. ‘Well, that sounds attractive’. I thought. It seemed an easy decision to decline the generous offer. Their rationales for the merger were greater economies of scope and scale, and increased market power. However, they seemed to have forgotten that they had ceded control to us. We suspected that this was really about another raw materials supply contract at elevated prices from Dresden’s upstream operation. The proposed deal made little sense as major reorganisations are hard enough to do well anyway, but whilst merging into another business, there was little prospect of success. In reality, management’s shareholding was unlikely to yield much value and losing their jobs was scarcely attractive. The refusal was not received well, and the resultant Zoom calls were at best stilted, verging on disagreeable. The concept of discussion seemed as far away as ever. Explaining our position cut little ice as that was of no interest to them. They had changed their minds and that was that.

A month or so passed and Dresden then made an offer to the management team to buy all their shares at twice the original price paid. The proposed alternative was that management paid the same for Dresden’s shares and paid back the bullet loan. After consultation with financial advisors and some modelling of options, the management team accepted the offer to buy out Dresden and repay the loan. They believed they could fund it out of business profits over the next year. The brothers promptly withdrew the offer. They clearly had thought that management would not be able to raise the money and so would be unable to accept their proposal to sell out.

A couple of months later Dresden started to reduce the trade credit. Proteus looked as though they were dependent upon this trade credit for cash during the difficult winter months when demand was low anyway. The third COVID lockdown along had further reduced demand so that Proteus was dependent on the trade credit. As always, cash forecasts were shared with Dresden who claimed that the business was not viable and would need another $2.0 Mn to survive. They proposed that there should be an equity issue shared pro rata to shareholdings, so management would need to find another $1.020 K out of their own pockets to stay in control. Otherwise, Dresden would buy up any surplus shares and take control. This would no doubt be followed by an unwelcome merger with MF and the management team losing their jobs.

To me, we did not need more cash as the business was improving rapidly in results as we removed cost. Our forecasts showed rapidly increasing cash and profit once we had navigated March and April when certain major payments were due. My guess was that the brothers had realised that the business value was set to increase rapidly and if they wanted to take control, they would have to do it before valuations rocketed. So their approach was to cut credit and force a share issue believing that the management team could not afford to stay in the game. In effect, their aim was to increase the stakes for all and trade on their bet that Dresden had deeper pockets than the team.

I politely declined their generous offer on the grounds that the business did not need it. Their response was to have their ‘independent’ accountants conduct a review of the accounts. It would not be too hard to guess what their opinion would be. Even with independent accountants ‘he who pays the piper calls the tune’.

Reflection

-

How ethical is this in your view? Is it anything more than boardroom power politics?

-

Clearly choosing a partner carefully is important. Do you think this battle for power is unusual in joint ventures?

Discussion

In boardroom battles, there are no rules other than complying with the law and the governance processes on which the business is established. Economic value seems to trump any other values and ethics. Indeed, the articles and shareholder contract provide the legal framework within which the battles for power operate.

In joint venture type relationships such as this, it is usual for the objectives of the partners to develop and diverge over time. This frequently leads to disputes between the partners who are effectively married under the contracts. Exiting is very difficult, as it is almost impossible to sell a significant share of a business with a disaffected partner attached. As a consequence, the exit of either partner is normally at an under value as they can only sell out to the other partner. In such a limited market for the shares, they will be cheap. Around 80% of joint ventures are sold to one partner. Around 50 to 70% end up in failure and value destruction as a result of diverging objectives.

In this case, one partner somewhat unusually changed their objectives almost immediately, once the deal was done. As they had not considered the position of the management team when changing their minds, they were somewhat surprised by a refusal. After that, rather than offering a sensible figure to buy management out they indulged in various devious activities to buy the business on the cheap.

In board games, few are interested in what is fair and reasonable but rather how they can extract value; others are viewed as needing to look after themselves during the battle for power.

Lessons

-

Be very careful whom you trust in business. When it comes to money, trust can become a scarce commodity. Do not believe that friendly reasonable sounding people are not interested in extracting maximum value from whoever controls it.

-

The objectives of partners often change over time. This may create tensions and ultimately lead to divorce. One side of the JV shareholders, if not both, usually has ambitions regarding overall control that may not have been previously discussed with the other partner.

-

Joint ventures frequently develop into battles for control either in the boardroom or by controlling the management team. Other means involve the functions, technology, or raw materials supplied by each side to the business.

-

Consider with whom you make strategic alliances. There has been enormous growth in joint ventures over the last 20 years as firms realise that co-operation can yield significant benefits. However, exits have to be carefully planned before marriage occurs to avoid major disputes when objectives change.

Reflections

This chapter has identified several key issues and questions:

-

Why ethics and values matter and the potential consequences of poor ethical standards.

-

When globalising the decision to enter many countries is accompanied by ethical risk of varying degrees. How will you manage this risk without creating unacceptable risks for your people?

-

Perceived unethical behaviour of the top team has a significant influence on the organisation’s culture and the way challenges are managed.

-

Boards are rarely aware of the true state of ethics within their organisation unless they conduct regular confidential surveys of their staff (Soltes, 2019). To be effective surveys need a top team response.

-

An organisation’s ethics and values are placed under real stress when stakes are high. However, maintaining and upholding values usually has a lower real cost than anticipated and significant long-term benefits in terms of perceived ethical reputation, both internally and externally.

-

In boardroom battles, ethics are rarely a consideration in the quest for control. Be careful when selecting partners.

-

Unethical cultures often exhibit certain symptoms. Be aware of those symptoms and be willing to ask the important questions.

References

Bolden, R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: A review of theory and research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(3), 251–269.

Caldwell, C., Ichiho, R., & Anderson, V. (2017). Understanding level 5 leaders: The ethical perspectives of leadership humility. Journal of Management Development. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmd-09-2016-0184

Ciulla, J. B., Knights, D., Mabey, C., & Tomkins, L. (2018). Guest editors’ introduction: Philosophical approaches to leadership ethics II: Perspectives on the self and responsibility to others. Business Ethics Quarterly, 28(3), 245–250.

Collins, J. (2016). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap and others don’t. Instaread.

Crane, A., Matten, D., Glozer, S., & Spence, L. (2019). Business ethics: Managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the age of globalization. Oxford University Press.

Downe, J., Cowell, R., & Morgan, K. (2016). What determines ethical behavior in public organizations: Is it rules or leadership? Public Administration Review, 76(6), 898–909.

Driver, J. (2014). The history of utilitarianism. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/

Epley, N., & Kumar, A. (2019). How to design an ethical organization. Harvard Business Review, 97(3), 144–150.

Fleming, P., Zyglidopoulos, S., Boura, M., & Lioukas, S. (2020). How corruption is tolerated in the Greek public sector: Toward a second-order theory of normalization. Business & Society, 61(1), 191–224. 0007650320954860.

Fotaki, M. (2020). Whistleblowers counteracting institutional corruption in public administration. In Handbook on corruption, ethics and integrity in public administration. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Healy, P., & Serafeim, G. (2019). How to scandal-proof your company a rigorous compliance system is not enough. Harvard Business Review, 97(4), 42–50.

Isaac, M. (2019). Super pumped: The battle for Uber. WW Norton & Company.

Jennings, M. M. (2006). Seven signs of an unethical culture. St Martin’s Press.

Messick, D. M., & Bazerman, M. H. (2001). Ethical leadership and the psychology of decision making. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice. Sage Publications.

Shotter, J., & Tsoukas, H. (2014). In search of phronesis: Leadership and the art of judgment. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 13(2), 224–243.

Soltes, E. (2019). Where is your company most prone to lapses in integrity? A simple survey to identify the danger zones. Harvard Business Review, 97(4), 51–55.

Turner, N., Barling, J., Epitropaki, O., Butcher, V., & Milner, C. (2002). Transformational leadership and moral reasoning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 304.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Colley, J., Spyridonidis, D. (2022). Ethics and Values: Negotiating a Complex Minefield. In: Unprecedented Leadership. Palgrave Executive Essentials. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93486-6_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93486-6_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-93485-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-93486-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)