Abstract

Not all legal bases can be useful for automated decision-making, eventually not even the ones provided by Article 22 GDPR. The method used to make automated decisions and to profile data subjects using Machine Learning technologies is still somehow obscure to the data protection community—and beyond. Strengths and weaknesses of automated decisions should dispel some myths and encourage a better understanding of this complex phenomena and its functioning.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016, on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), OJ 2016 L 119/1.

- 2.

“Algorithm: a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations, especially by a computer.” Future of Privacy Forum (2018).

- 3.

Article 29 Working Party (2017).

- 4.

Brkan (2019).

- 5.

A politically exposed person is someone who has been entrusted with a prominent public function. For most financial institutions, they constitute a potential compliance risk.

- 6.

Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)13 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on the protection of individuals with regard to automatic processing of personal data in the context of profiling.

- 7.

“A comprehensive approach should determine specific legal requirements not only for the usage and further processing of personal data but already for the collection of data for the purpose of profiling and the creation of profiles as such.” Article 29 Working Party (2013). Advice paper on essential elements of a definition and a provision on profiling within the EU General Data Protection Regulation. Article 29 Working Party (2013).

- 8.

To understand the role of data in Machine Learning processes see: Singh et al. (2016).

- 9.

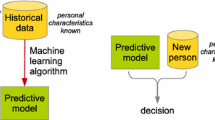

“Once a machine learning programme has been trained, the method it uses to recognize patterns in new data is called a model. The model is what is used to perform tasks moving forward, with new data.” Future of Privacy Forum (2018).

- 10.

Even past behaviours could be foreseen as an “anomaly detection” (something I should have done but I did not) or as a “propensity” (something I am going to do in the near future).

- 11.

Datatilsynet, The Norwegian Data Protection Authority (2018).

- 12.

Kamarinou et al. (2016).

- 13.

“Narrow artificial intelligence: An application of artificial intelligence which replicates (or surpasses) human intelligence for a dedicated purpose or application” Future of Privacy Forum (2018).

- 14.

This definition seems appropriate for the purpose of this paper, however it is narrower than more commonly used ML definitions (clustering, for instance, is not covered by this definition). Session with Ralf Herbrich, Quora. https://www.quora.com/session/Ralf-Herbrich/1.

- 15.

Samuel (1988).

- 16.

Kelnar (2016).

- 17.

O’Neil (2016).

- 18.

Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, OJ 1995 L 281/31.

- 19.

Veale and Edwards (2017).

- 20.

Kamarinou et al. (2016).

- 21.

Article 29 Working Party (2017).

- 22.

Article 22(2) of the GDPR (n. 1).

- 23.

Article 29 Working Party (2017).

- 24.

Article 29 Working Party (2014).

- 25.

Brkan (2019).

- 26.

Article 29 Working Party (2014).

- 27.

“The measure envisaged should be the least intrusive for the rights at stake: o Alternative measures which are less of a threat to the right of personal data protection and the right for respect of private life should be identified. o An alternative measure can consist of a combination of measures. o Alternatives should be real, sufficiently and comparably effective in terms of the problem to be addressed. o Imposing a limitation to only part of the population/geographical area is less intrusive than an imposition on the entire population/geographical area; a short-term limitation is less intrusive than a long-term; the processing of one category of data is in general less intrusive than the processing of more categories of data. o Savings in resources should not impact on the alternative measures – this aspect should be assessed within the proportionality analysis, as it requires the balancing with other competing objectives of public interest”. European Data Protection Supervisor (2017). Assessing the necessity of measures that limit the fundamental right to the protection of personal data: A toolkit. https://edps.europa.eu/sites/edp/files/publication/17-06-01_necessity_toolkit_final_en_0.pdf. 11 April 2017.

- 28.

So this suggests that CVs should be received in envelopes and processed like in the good old days.

- 29.

Datatilsynet, The Norwegian Data Protection Authority (2018).

- 30.

“if profiling does not involve the processing of data relating to identifiable individuals, the protection against decisions based on automated profiling may not apply, even if such decisions may impact upon a person’s behaviour or autonomy”. Schreurs et al. (2008).

“The protection against solely ADM might not apply if the data processed are anonymized”. Savin (2014).

- 31.

Brkan (2019).

- 32.

German Act to Adapt Data Protection Law to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and to Implement Directive (EU) 2016/680 (DSAnpUG-EU) of 30 June 2017.

- 33.

“This provision allows for automated decisions in tortious – and not contractual – relationship between the insurance company of the person who caused damage and the person who suffered damage, under the condition that the latter wins with her claim”. Brkan (2019).

- 34.

Article 29 Working Party (2018).

- 35.

- 36.

Brkan (2019).

- 37.

“In algorithmic context, transparency relates to the degree the internals of the algorithms can be seen and understood; for instance, exposing the features of the data the learned model takes into account, the associations and rules that were derived, and the extent to which the model relies on these.” Singh et al. (2016).

- 38.

“Decision tree: a decision support tool that uses a tree-like graph or model of decisions and their possible consequences, including chance event outcomes, resource costs, and utility”. Future of Privacy Forum (2018).

- 39.

Pasquale (2015).

- 40.

“A variation of a machine learning model that, taking inspiration from the human brain, is composed of multiple processing layers”. Future of Privacy Forum (2018).

- 41.

Singh et al. (2016).

- 42.

Singh et al. (2016).

- 43.

Singh et al. (2016).

References

Article 29 Working Party. (2013). Advice paper on essential elements of a definition and a provision on profiling within the EU General Data Protection Regulation. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/other-document/files/2013/20130513_advice-paper-on-profiling_en.pdf

Article 29 Working Party. (2014). Opinion 06/2014 on the notion of legitimate interests of the data controller under Article 7 of Directive 95/46/EC. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2014/wp217_en.pdf

Article 29 Working Party. (2017). Guidelines on automated individual decision-making and profiling for the purposes of Regulation 2016/679. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/article29/item-detail.cfm?item_id=612053. Adopted on 3 October 2017 as last Revised and Adopted on 6 February 2018.

Article 29 Working Party. (2018). Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/article29/item-detail.cfm?item_id=623051. Adopted on 28 November 2017 as last Revised and Adopted on 10 April 2018.

Brkan, M. (2019). Do algorithms rule the world? Algorithmic decision-making in the framework of the GDPR and beyond. International Journal of Law and Information Technology. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3124901

Datatilsynet, The Norwegian Data Protection Authority. (2018). Artificial intelligence and privacy. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://www.datatilsynet.no/globalassets/global/english/ai-and-privacy.pdf

European Data Protection Supervisor. (2017). Assessing the necessity of measures that limit the fundamental right to the protection of personal data: A toolkit. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://edps.europa.eu/sites/edp/files/publication/17-06-01_necessity_toolkit_final_en_0.pdf

Future of Privacy Forum. (2018). The privacy expert’s guide to artificial intelligence and machine learning. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://fpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FPF_Artificial-Intelligence_Digital.pdf

Kamarinou, D., Millard, C., & Singh, J. (2016). Machine learning with personal data. In R. Leenes, R. van Brakel, S. Gutwirth, & P. De Hert (Eds.), Data protection and privacy: The age of intelligent machines. Hart Publishing.

Kelnar, D. (2016). The fourth industrial revolution: A primer on Artificial Intelligence (AI). Medium. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://medium.com/mmc-writes/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-a-primer-on-artificial-intelligence-ai-ff5e7fffcae1

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

Samuel, A. L. (1988). Some studies in Machine Learning using the game of checkers. In D. N. L. Levy (Ed.), Computer Games I (pp. 335–365). Springer.

Savin, A. (2014). Profiling and automated decision making in the present and new EU Data Protection Frameworks. Paper presented at 7th International Conference Computers, Privacy & Data Protection, Brussels, Belgium.

Schreurs, W., Hildebrandt, M., Kindt, E., & Vanfleteren, M. (2008). Cogitas, Ergo Sum. The role of data protection law and non-discrimination law in group profiling in the private sector. In M. Hildebrandt & S. Gutwirth (Eds.), Profiling the European Citizen (pp. 241–270). Springer.

Singh, J., Walden, I., Crowcroft, J., & Bacon, J. (2016). Responsibility and machine learning: Part of a process. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2860048

Veale, M., & Edwards, L. (2017). Clarity, surprises, and further questions in the Article 29 Working Party draft guidance on automated decision-making and profiling. Computer Law & Security Review: The International Journal of Technology Law and Practice, 34(2), 398–404. Retrieved September 1, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3071679

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Del Gamba, G. (2022). Machine Learning Decision-Making: When Algorithms Can Make Decisions According to the GDPR. In: Borges, G., Sorge, C. (eds) Law and Technology in a Global Digital Society. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90513-2_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90513-2_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-90512-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-90513-2

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)