Abstract

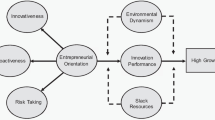

Entrepreneurial Orientation is a prominent topic within the field of management research as it has been subject to more than four decades of theoretical and empirical inquiry, and is widely acknowledged as a strong predictor of firm performance. Therefore, with the aim of continual development of the theory and research on this topic of interest, the current chapter portrays and identifies the determinants of Entrepreneurial Orientation and its implications on firm performance through its five dimensions: namely innovativeness, proactiveness, risk-taking, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness. Studies exploring the antecedents of Entrepreneurial Orientation and the factors that nurture it are scarce, especially when tackling the context of SMEs. Hence, its origins remain unclear, constituting a promising research direction and a fertile area that requires further development. Thus, this chapter draws on prior research to suggest and develop a theoretical framework concerned with SMEs’ strategic orientation and entrepreneurial practices, seeing the immense and inevitable contribution of SMEs to their local and regional economies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Firms constantly face complex environments manifested by increased competition, and fast-paced changes in technologies and the lifecycle of deliverables. This reality triggers them to foster and sustain entrepreneurship, considered as a permanent attitude that firms must develop (Dess et al., 2008) and an objective for them to advance their alertness to a globalized and dynamic environment (Aloulou, 2002). Actually, the wealth and economic expansion of a country is a result of its entrepreneurial function reflected in the competitiveness and performance of its operating firms. Despite the many attempts by classical and neoclassical theorists to agree on a single definition of entrepreneurship, it seems to depend on the perspective of the party describing it. All related definitions however, have commonly emphasized the role of opportunities: their recognition, their evaluation and their exploitation in managing the opportunity development process.

Therefore, the field of entrepreneurship has occupied an extensive part of strategic management literature as of late, given that the scholarly conversation over this field doesn’t concern the firm creation only, but outspreads to discuss entrepreneurship within an existing firm (adapting and managing a venture as per Aloulou, 2002), known in other terms as Corporate Entrepreneurship (Zahra & Covin, 1995; Covin & Miles, 1999). In fact, Schumpeter (1942) has been one of the first to shift attention from the individual entrepreneur to entrepreneurial firms, seeing their capability in dedicating more resources to innovation. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) emerged out of this field, and is considered as the construct that best describes the firm’s entrepreneurial strategic orientation (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003, 2005) that holds the methods, practices and decision-making processes that firms rely on to act in an entrepreneurial manner (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996).

On the one hand, the most-studied dependent variable in strategy and entrepreneurship research is firm performance (Covin & Slevin, 1991). Therefore, there is an everlasting concern to encourage firms to become more entrepreneurial in ways that enhance their performance and their international competitiveness. EO has been broadly acknowledged as a strong predictor of firm performance, though results in this field still appear to be contradictory, which incites researchers to thoroughly investigate this relationship especially in a developing country such as Lebanon, considering that EO doesn’t function in the same way within different environments (Covin & Slevin, 1989). Actually, developing economies have lately witnessed an upsurge in entrepreneurship where private businesses are perceived to be less growth-oriented when compared to their Western counterparts (Manev et al., 2005). Since the majority of entrepreneurship research studies are conducted in developed Western countries, the assumption is that entrepreneurship barely exists in developing economies (Ratten, 2014).

However, criticism over the relationship between EO and firm performance focussed on the investigation of companies where a prominence of the role of EO in smaller firms had been advocated (Aloulou & Fayolle, 2005; Rauch et al., 2009). This prominence is due first to the increasing number of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) that surpass the number of any other type of firm among different countries. Indeed, SMEs account for more than 95% of Lebanese companies (Koldertsova, 2006) which gives Lebanon a reputation as an exciting entrepreneurial landscape for SMEs. The country has been focusing on the existence of SMEs and their development as part of a reconstruction plan that aims to advance the economy and improve its wealth. Second, this prominence is perceived to be due to the changing environment that these SMEs face, and the acknowledged need of elaborating an entrepreneurship framework adapted exclusively for them, seeing the difference that exists between SMEs and large enterprises (Aloulou, 2002).

On the other hand, there have been few attempts to understand the factors that nurture EO, and its origins remain unclear, therefore this constitutes a fertile area that requires further development (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011; Miller, 2011; Wales, 2016). The role that internal factors play within EO is perceived to be accorded much importance when emphasizing the relationship between EO and firm performance. Thus, a complementarity between the firm’s resources and its decision-making exists in the aim to attain profitability (Miller, 2003), and a connection between EO and theories from different disciplines occurs (Miller, 2011). This chapter builds on this work to attain both of its goals. The first goal considers the influence that firm resources, dynamic capabilities (DCs), social capital (SC) and additional internal factors have on EO, whereas the second goal elaborates the relationship between EO and firm performance while pertaining to the context of SMEs in both goals.

In this context, Resource-Based View (RBV) has been defined as the theory of competitive advantage, where to be productive, firms’ resources must collaborate. This theory also explains that what lies behind the firm’s competitive advantage relies on the firm’s capability to provide the optimum use of its resources (Barney, 1986, 1991). DCs are considered as the ability of the firm to persistently adapt and reconfigure its resource base to address fast-moving environments and attain a competitive advantage, whereas SC depicts the social interaction and network of relationships in which the firm is disposed to get access to useful information and additional resources and knowledge, thus facilitating the entrepreneurial activity. Additional internal factors that consider both the organization and the entrepreneur running it, are perceived to fit on some theoretical lenses that exist to enhance the literature on EO’s antecedents. These factors pertain to the previous skills and experience of the entrepreneur (known as the subjectivist theory of entrepreneurship), their self-efficacy, the entrepreneurial Dominant Logic (DL), and the organization’s culture and structure considered as intangible resources that are hard to imitate. An additional part will be reserved to pass by these theoretical lenses.

Entrepreneurship and SMEs’ Contribution to Developing Economies

Seeing that research on entrepreneurship has roots in economics, Cantillon (1755) was the first economist to introduce entrepreneurship and recognize the entrepreneur as a significant economic factor responsible for all the exchange in the economy. Afterward, world economies started to consider entrepreneurship among their individuals and firms. This is because entrepreneurship is considered and acknowledged to be a main engine and a vital source of economic growth and expansion (Henderson, 2002). Indeed, Henderson (2002) perceived entrepreneurs as an added value to local economies that create entrepreneurial development strategies. This added value has implications at both local and national levels. Locally, economies with frequent entrepreneurship actions witness a serious increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), whereas nationally, entrepreneurs are capable of creating new employment opportunities as well as leading to exceptional wealth increase. In fact, both entrepreneurship and the attainments of entrepreneurial societies contribute to the competitiveness and efficiency of global markets (Audretsch, 2007). From this viewpoint, both policymakers and entrepreneurs are considered to be engaged in entrepreneurship, despite the differences that exist in their aims. Policymakers focus on entrepreneurship as the source of job opportunities, causing structural change and generating a competitive advantage especially in global markets; while entrepreneurs perceive it as an opportunity of exploitation, generating a lifetime career and further high gains (Kuckertz & Wagner, 2010).

However, the growing interest in the field of entrepreneurship is accompanied with a prominence attributed to SMEs thought of as a source of innovation and competitiveness (Milovanovic & Wittine, 2014) for the role they play in stimulating entrepreneurial skills. The interest in SMEs has been renewed due to major enhancements performed in both industries and markets (Caner, 2010). Indeed, the economy of today is different from the economy of the nineteenth century and globalization accentuates the role of SMEs in providing a healthy climate in which to operate businesses. This is because they are considered to foster income growth, international exchange and economic development. The economic importance of SMEs has been much witnessed as of late, especially that larger firms have been performing mass layoffs (Van Stel et al., 2005) and SMEs offer new job opportunities and provide new products and services to the market (Henderson, 2002). In this context, Bouri et al. (2011) have presented the implications of SMEs’ growth on the domestic economic development when they stated that an increase in the growth of an SME leads to both a direct and indirect increase in GDP. The direct increase occurs through the increased profits and the added value accompanied accordingly, while the indirect increase is produced by the innovation and macro-economic resilience of the economy.

Most importantly, since the early 1980s SMEs began looking for innovation mechanisms and ways of diminishing their costs. This had the aim of opting for a more competitive offering than large corporations (Caner, 2010). In this context, SMEs are perceived to have a competitive structure that makes them respond promptly to the newest demands, technologies and market improvements as well as having the ability to resist economic crises (Schumacher, 1973). Also, they constitute the best workplace for potential and skilled employees further to the training programs they offer to their actors (Yılmaz, 2004). SMEs are capable of employing more than 60% of a country’s labor force as well as contributing to almost 50% of the productivity of a given sector (Hill, 2001), for around 85% of new jobs in the US are provided by small businesses (Audretsch, 2002). However, constituting specifically the emerging markets and economies with “weak institutions” such as the Middle Eastern countries, it’s found that most of these countries have recently started to adopt free-market systems. In fact, SMEs’ contribution to total employment is up to 60%, and up to 40% of the GDP in emerging countries as stated by the World Bank, excluding the existence of informal SMEs. As present, approximately 400 million Microenterprises and SMEs (MSMEs) exist in emerging economies, in which the majority are informal. The difference in the number of formal SMEs that exist between emerging economies and developed ones urges on the importance of the role that governments play in enhancing their economies through SMEs (Ndiaye et al., 2018). Nevertheless, in an estimation projection for the coming fifteen years made by the World Bank for the Asian and Sub-Saharan African countries, over 600 million workers are estimated to be joining the workforce worldwide, which eventually leads to an estimate that four out of five new jobs will be generated by SMEs. On this same note, and in a report prepared for an agenda workshop concerning Lebanon National Investment improvement, it has been stated that SMEs constitute 99% of companies in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region (Koldertsova, 2006).

SMEs are perceived to be the rescue plan for the majority of struggling economies. Both regulatory as well as financing initiatives can lead the path to better employment opportunities and higher GDP. Seeing this, the MENA region has started to pay attention to the emergence and growth of SMEs, although the competitiveness of these SMEs is still considered low compared to their regional and international counterparts. One of the main reasons behind this is the minimal access to external financing granted to these firms. In this context, Aloulou and Fayolle (2005) stated that when a small firm is compared to a large firm, it’s noticed that the small firms are lacking in resources and capabilities compared to the large firms. This has been in line with Storey (1994) arguing that small firms face difficulties in having access to financial capital which may impede their growth potential. However, and despite the existence of a considerable number of banks and financial institutions in the MENA region, only 2% of the Gulf banks’ loans are provided to SMEs, which is perceived to be due to the unavailability of a credit history for these SMEs, thus leading to a lack of sufficient information to provide the banks with (Bouri et al., 2011). Therefore, it has been argued that governments must interfere to close the financing gap and contribute to developing SMEs’ institutional environment (Ratten, 2014). This is another brick in the many initiatives that governments of most emerging economies, especially the Middle Eastern ones, must accomplish to keep up with the expectations of their people, the young leaders and the nascent entrepreneurs as well as to ensure long-term sustainability and development. Thus, this has been emphasized during the Arab Spring movements that aroused resistance against all forms of corruption that exist in the Arab countries and the inequality in employment opportunities. Against this background, Lebanon has been noted for its energetic entrepreneurial background, depending on SMEs to contribute to its economy. This began two to three decades agpo, when Lebanon started leveraging efforts to develop its ecosystem for SMEs’ emergence and development, allowing innovative and creative entrepreneurs to venture and initiate their ideas. However, and due to the continuous political and economic instability that the country has experienced, SMEs in Lebanon face many challenges. With an aim to overcome these challenges (Miles et al., 1978) and to have the ability to thrive in highly competitive or unstable economic environments, these SMEs need to adopt a suitable strategic response (Covin & Slevin, 1989) such as EO for long-term success.

Entrepreneurial Orientation and Interrelationship with Firm Performance

EO has been initially captured as the construct that holds the factors that are essential and relevant for making a firm entrepreneurial (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983). It concerns the processes, methods and decision-making activities that lead to a new entry (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) and constitutes the process of entrepreneurial strategy-making that entrepreneurs rely on to ensure the firm’s well-being and competitive advantage (Rauch et al., 2009). Moreover, Morris et al. (1996) perceived the entrepreneurial business activity as opportunity-driven and based on an opportunity-driven mindset, which is further translated as the discovery and exploitation of new opportunities that may further affect change. The perception, discovery and exploitation of opportunities are perceived to happen at the firm level, and therefore Lumpkin and Dess (1996) defined EO as a firm-level phenomenon considering the small firm as an extension of the leader individual. Indeed, management scholars have been much interested in entrepreneurship research to a point where the focus of their studies has shifted from the entrepreneurs themselves to the growth of their firms (Aloulou, 2002).

The origins of EO go back to the work of both Mintzberg (1973) and Khandwalla (1976/1977). However, its definition as a concept in the literature has been first acknowledged by Miller (1983) who considered EO (without mentioning it as a term) as a composite dimension including innovativeness, risk-taking and proactiveness. Similarly, Covin and Slevin (1989) considered EO as a unidimensional construct in a way such that when all three dimensions exist collectively and work concurrently, the firm will be considered to have an EO, and thus be entrepreneurial (Covin & Wales, 2012). However, a decade later, another operationalization of EO appeared, suggested by Lumpkin and Dess (1996) that added two other dimensions: autonomy and competitive aggressiveness. Within this view, emphasis has been laid on the practicality of viewing EO as a multidimensional construct, yielding the possibility that only some of the dimensions exist in the case of a successful new entry, which in other terms means that these dimensions may vary independently rather than co-vary. This eventually has underscored the independent effect of each of the dimensions, treated as separate constructs.

On a complementary note, the unidimensional view of EO has already been proved in previous research to have a relationship with firm performance. Therefore, it is recommended to assess the unique effects of each of the five dimensions on firm performance. Besides, many researchers (e.g., Awang et al., 2009; Hughes & Morgan, 2007; Kreiser et al., 2002) have led studies adopting and defending the multidimensional conceptualization. Therefore, we describe each dimension individually. Starting with Autonomy, it is argued to be split into two different directions as per Lumpkin and Dess (1996). Within the first direction, autonomy is perceived to be autocratic and characterized by strong leaders, especially in smaller firms. The second direction describes the firm’s actors’ tendency to act autonomously from strong leaders and to pursue opportunities independently. Dess and Lumpkin (2005) emphasized the importance of motivating entrepreneurial thinking within a firm, recognizing it as a driver of competitive advantage. Indeed, a person may have a solid aspiration in having the freedom to develop and implement ideas (Li et al., 2009). In their turn, Hughes and Morgan (2007) perceived autonomy as a main driver of flexibility, permitting the firm to respond rapidly to changes in its environment and markets. Many studies have defended the positive influence that autonomy has on firm performance, and argued that displaying autonomy in a firm inspires its actors to act more entrepreneurially, leading to superior competitiveness and enhanced firm performance (Awang et al., 2009; Coulthard, 2007; Frese et al., 2002; Prottas, 2008). Second, talking about Competitive Aggressiveness, this is the strength of the posture that a firm takes when threats from its rivals appear. By this posture, the firm aims to challenge and undo its competitors. According to Lumpkin and Dess (1996), being competitively aggressive can secure and improve market positioning. Similarly, Dess and Lumpkin (2005) expounded how companies with competitive aggressiveness are ready to “do battle” with competitors either to gain market share or to keep the share they already have. In other terms, companies may cut their prices or even sacrifice profitability in favor of market share. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) argued that improvement in firm performance can be achieved by using aggressiveness, since the firm’s competitiveness at the expense of rivals will increase by discouraging competitors in the market. Later, Lumpkin and Dess (2001) found that a positive relationship between competitive aggressiveness and firm performance exists, and which was later confirmed in the study performed by Frese et al. (2002). Moving to Innovativeness, it was first recognized as entrepreneurial innovation (Schumpeter, 1934, 1942) and considered as the core of entrepreneurship (Covin & Miles, 1999; Drucker, 1985; Henderson, 2002). It is the implementation of new and creative methods that ensure a firm’s survival in highly competitive markets (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2005) and yield new products, services and processes (Aloulou & Fayolle, 2005; Pittino et al., 2017; Schumpeter, 1934). Innovativeness is a key component of entrepreneurship, seeing that it reflects a way in which firms pursue new opportunities (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996), build differentiation and improve solutions that challenge those of its competitors (Hughes & Morgan, 2007) as well as to overcome challenges and attain profitability (Hult et al., 2004). Previous research emphasized the role that innovation plays in achieving a firm’s competitiveness and attaining a higher firm performance (Coulthard, 2007; Hameed & Ali, 2011; Hughes & Morgan, 2007). Indeed, innovativeness has proved to lead to the firm’s success (Awang et al., 2009; Frese et al., 2002). Considering Proactiveness, it has been given little attention in scholarly articles, while it encompasses the most important perspective. It concerns the active and continuous search of the firm to pursue promising opportunities (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990; Venkatraman, 1989) and to anticipate future demands and trends in the market. The pursuit of opportunities is vital in entrepreneurship (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). A proactive firm is the one that looks in advance of the competition, and is keen to introduce newness to the market. Indeed, Jalali et al. (2014) disclosed that proactiveness is essential for firms that are in the process of innovating and looking to attain a competitive advantage. Proactiveness incorporates the firm’s alertness to customers’ needs and its openness to market indications (Hughes & Morgan, 2007). Both Coulthard (2007) and Hughes and Morgan (2007) were among the researchers that studied proactiveness in regard to the developmental stage of the firm, stating that higher levels of proactiveness were associated with higher levels of performance. Also, in a study on Indonesian SMEs, Kusumawardhani (2013) found that proactiveness is the only dimension of EO that is positively related to firm performance. Finally, coming to Risk-Taking, this refers to bearing the risk of venturing into the unknown and taking bold actions in some undefined situations such as committing resources for uncertain returns. The concept of risk-taking, used frequently to describe entrepreneurship (Aloulou & Fayolle, 2005), actually refers to the adoption of calculated business risks that entrepreneurs make (Brockhaus, 1980). Without risk-taking (constructive risk-taking as per Miller, 1983), firms tend to be conservative when facing market changes and tend to refrain from introducing innovations. Consequently, this can result in weaker performance (Hughes & Morgan, 2007). However, previous findings (Frese et al., 2002; Hameed & Ali, 2011) revealed a direct positive impact that risk-taking has on the firm performance.

Most entrepreneurship scholars have tended to explain firm performance by investigating the firm’s EO (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003), which accredited performance to be one of the most dependent variables examined in the EO literature. Firm performance is the best indicator of how a company’s operations and activities are being handled and how successfully the firm is operating. Notwithstanding this interest, studies observing this relationship have been crowned with mixed results. While some have been able to find a positive correlation between EO and firm performance (e.g., Awang et al., 2009; Frese et al., 2002; Hameed & Ali, 2011; Hughes & Morgan, 2007; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003, 2005), other studies did not succeed in finding any correlation (e.g., Covin et al., 1994; Lee et al., 2001) or have found at least that this relationship is not linear (Zahra & Garvis, 2000). In this context, Bhuian et al. (2005) have shown that the EO-performance relationship is an inverted U-shape, for in the case of some markets or conditions, higher levels of EO are not essentially needed for a firm to perform better. However, Rauch et al. (2009) have attributed these differences in results to the adoption of different methodologies and research samples.

Moreover, and on a complementary note, the historical perception of small businesses has been different from that of today. Birley and Norburn (1985) stated that small businesses were viewed as “country cousins” and mainly patronized by larger firms when undertaking a heavy business. Accordingly, studies conducted on large firms have been more visible than those concerning SMEs in the EO literature. In this context, Aloulou and Fayolle (2005) stated that the vast majority of studies that investigated the relationship between EO and firm performance were conducted in the framework of large companies rather than SMEs. However, the cases when EO is investigated in large firms operating in developed countries can’t be generalized to the case of smaller firms that are mainly centered on their CEOs/founders (Fini et al., 2012; Wiklund, 1998). Therefore, many scholarly conversations focussed on the presence of EO in SMEs (e.g., Aloulou, 2002; Aloulou & Fayolle, 2005), and acknowledged its importance in enhancing SMEs’ performance (Rauch et al., 2009).

Firm Resources, Dynamic Capabilities (DCs) and Entrepreneurial Orientation

The existence of entrepreneurial opportunities emerges from the difference in value attributed to resources when these resources are converted from inputs to outputs, considering that this attribution varies according to the individual’s beliefs (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Haynie et al. (2009) have suggested that reflecting on both existing and future resources surrounds the process of opportunity development, i.e., discovery, evaluation and exploitation. They argued in this context that when entrepreneurs evaluate an opportunity, they focus on their current firm resources and the resources that they may have in the future to decide whether to exploit this opportunity or not. Moreover, Cai et al. (2018) argued that both opportunity development and resource development are main topics in entrepreneurship because the entrepreneurial process is opportunity-based, whereas resources can secure it. Therefore, an integrated view of the convergence of both opportunity development and resource development has occurred, believing that the entrepreneurial behavior is a series of actions by which the entrepreneur acquires resources in order to pursue opportunities. Indeed, Haynie et al. (2009) argued that existing resource recognition is primordial in opportunity evaluation, whereas Haugh (2005) highlighted the importance of both resource acquisition and integration in the whole opportunity development process, and particularly in the opportunity exploitation phase. Besides, Sirmon et al. (2007) argued that resource management is core in building a firm’s resources portfolio, bundling these resources in order to build capabilities and further create value and the business sustainment.

Firm-level entrepreneurial activity and resources are appropriately related through RBV specifically with the case of high-tech venturing (Miller, 2011) where a shortage of resources can harm the entrepreneurial activity of top key persons in the organization. Indeed, much of entrepreneurship literature focusses on the difficulty encountered in obtaining resources, especially financial accessibility, for it is seen that even highly entrepreneurial firms are hindered in achieving their optimum performance when there is unavailability of adequate internal resources. Entrepreneurship has its share in the resource-based framework (Conner, 1991) since resource-based theory discusses new visions in entrepreneurial decision-making (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001). Indeed, Alvarez and Busenitz (2001) state that RBV emphasizes the heterogeneity of resources, whereas entrepreneurship emphasizes the heterogeneity in beliefs about these resources’ value. Irava and Moores (2010) stated however, that the heterogeneity of beliefs may grow into a robust resource, thus making the connection between RBV and entrepreneurship as a value-added proposition. In fact, Penrose (1959) has been the first to introduce the concept of resources in the literature, and RBV has been primarily defined as the theory of competitive advantage, where to be productive, firms’ resources must collaborate. It explains that what lies behind the firm’s competitive advantage does not concern the industry composition, but instead relies on the firm’s capability to provide the optimum use of its resources (Barney, 1986, 1991) by developing internal strengths and acquiring complementary resources. In this context, Chandler and Hanks (1994) argued that the perception of resource availability is related to entrepreneurs’ beliefs in acquiring resources. These beliefs relate to the individual’s self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977, 1989) that has its effect on resources’ acquisition and the whole entrepreneurial activity of the firm particularly in the case of an SME. Similarly, a framework has been developed to show CEOs’ decisions on resources allowance driving their firms to engage in entrepreneurial behavior. This is because due to their size, these SMEs encounter challenges in attaining and combining the appropriate resources that allow them to formulate competitive strategies (Aloulou, 2002).

However, many researchers have tried to derive resource categorization schemes (Miller & Shamsie, 1996). Based on the perception of Wernerfelt (1984), resources are considered as anything that can be thought of as a strength or a weakness of the firm, defined as the tangible and intangible assets that semi-permanently exist. Thus, firm-specific internal factors are of great importance when considered within the RBV framework, and strategy selection is based on the careful evaluation of these bundles of tangible and intangible resources (Galbreath & Galvin, 2008). Indeed, Barney (1991) affirmed that all of a firm’s resources (i.e., physical, human and capital) can be used by the firm to implement strategies that expand both its efficiency and effectiveness.

On the one hand, tangible resources encompass both physical and financial resources (Das & Teng, 2000). While physical resources are thought of as the technology undertaken by the firm, its plant and equipment, or even its geographic location (Barney, 1991), financial resources (Grant, 1991) are considered of critical importance especially for the case of small firms (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). Indeed, financial resources are the basis of all other resources, seeing that they can be easily converted into other types of resources (Dollinger, 1999). Within RBV, tangible resources are perceived to be easily imitated by competitors (Barney, 1991) for they are easily obtained in the factor markets (Teece, 1998). However, small firms still face many challenges when considering their access to financial capital and this has implications on their growth potential (Malhotra et al., 2007; Storey, 1994).

On the other hand, intangible resources are of great importance due to their influence on increasing the firm’s adaptability to the market’s expectations and needs, thus yielding a competitive offering (Miller & Shamsie, 1996). Knowledge-based resources specifically, are considered as a source of the firm’s ability to discover and exploit new opportunities (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). This chapter considers different types of intangible resources since recent approaches to firm resources focus on a wide variety of them. First, we perceive the top management team (Barney, 1991) as having the main influence on the firm’s well-being through the skills and capabilities of key people operating in the organization that hold specific managerial and technical knowledge (Manev et al., 2005). The complementarity of their skills and capabilities is essential (Carmeli & Tishler, 2004). Second, we are concerned with the firm’s employees, their creativity, innovativeness and expertise, considered as a source of competitive advantage. In fact, research on EO and its relationship with firm performance looks into human capital and interrelates it with many EO facets. On this same note comes the organizational reputation (Grant, 1991; Teece et al., 1997) that constitutes the information and response that different stakeholders present to reflect a given firm (Teece et al., 1997). Moreover, an emphasis is accorded to the Human Resource Management policies. Indeed, the recruiting criteria employed to grant individuals to join organizations in addition to the empowerment and training programs offered to the firm’s actors are considered of crucial importance. Finally, there exists the labor relations and open internal communications that grant a mixture of skills and sharing of function-specific knowledge among different areas within the organization (De Clercq et al., 2013) to effectively cooperate on innovative ideas (Miller, 1983). Reflecting on this, many EO scholars claim that a lack of resources impedes the entrepreneurial activity that leads to a firm’s growth, for the access to significant resources is the basis of strategic orientation (Covin & Slevin, 1991) and both organizational resources and EO are mutually correlated (Chen et al., 2007). Indeed, financial capital allows firms to pursue new opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005), encourages the firm’s innovativeness (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) specifically its product innovations (Lee et al., 2001; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005; Zahra, 1991), and favors its risk-taking propensity (Tsai & Luan, 2016; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). In addition, both intangible assets and capabilities considered as intangible resources are perceived to affect the firm’s innovativeness (Bakar & Ahmad, 2010). More specifically, knowledge and prior experience are found to be positively related to proactiveness (Farmer et al., 2011; Shane, 2000) and professional decision-making (Pennings et al., 1998) which favors actors’ autonomy within a firm. In this context, Barney (1991, from Hambrick, 1987) argued that managerial talent is the essential firm resource leading to the employment of almost all firm’s strategies. Besides, other researchers (e.g., Ferrier, 2001; Grimm et al., 2006; Ndofor et al., 2011) have acknowledged the importance of resources in competitive behavior. These relationships addressed to specific EO components when tackling their antecedents is favored in terms of expanding and advancing the EO-related academic conversation (Anderson et al., 2015) seeing that these components are separate constructs and must be individually examined, for they aren’t supposed to share all antecedents and consequences (Covin & Wales, 2012; George & Marino, 2011).

However, a further development of RBV into a dynamic recipe has taken place to explain the process by which these resources should be employed. The research on DCs has been evolving for more than a decade, and papers conducting them have been recently populating in the aim to change the static perspective of RBV. In Barney’s (1991) view, firms have the freedom as well as the ability to choose the bundle of resources that best fit their purpose, or even change on the bundle they have already chosen in order to achieve the desired competitive advantage. In this context, Teece et al. (1997) have developed the “Dynamic Capabilities” approach to understand the sources of wealth creation and the methods with which firms achieve and most importantly sustain a competitive advantage. Teece et al. (1997) have argued that dynamic and demanding environments often require firms to develop DCs to attain a competitive advantage, gain market shares and undo competitors in the industry, specifically considering those that are technology-based. Therefore, it has been defined by Zahra et al. (2006) that DC is the capability of the firm to extend or modify its resources in a way approved by its main decision-makers. By this, firms intend to create opportunities by reconfiguring their existent asset and resource bases. In their attempt to demonstrate the necessary fundamentals of DCs, Teece et al. (1997) have contrasted the concept to other models of strategy from which RBV has been considered.

In their turn, Jantunen et al. (2005) argued that in terms of grasping the right opportunities, having a value-added resource combination and enduring a competitive advantage, a firm must develop its DCs. They viewed that endorsing different and innovative organizational strategies and practices can enhance firm performance, and that their implementation can lead the firm to successfully reconfigure its asset base in a way to respond to its environment. Ambrosini and Bowman (2009) have tried to attribute DCs to real examples when they argued that the managerial processes are the main developers of DCs that convert the static type of resources into dynamic resources. By static resources, researchers meant both tangible and intangible resources. This has been similarly argued by Helfat and Martin (2015), who state that DCs are the tools that managers rely on to create, change and extend the firms’ decisions. In this context, it has been perceived that some capabilities in a firm may lead to a higher EO or affect the relationship between EO and its implications. Indeed, Zahra et al. (2006) argued that what encourages or stimulates the presence of EO in a firm is sometimes related to its DCs developed through operations. Similarly, Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. (2018) have found in their turn that DCs have a positive effect on EO as well as to mediate the relationship between social capital and EO. In contrast, it has also been argued in the academic conversation that EO can in its turn enhance the existence of capabilities and resources in any given firm.

By reconfiguring their asset base, it is actually easier for firms to profit from opportunities. However, when it’s the case of a rapidly changing environment known by its dynamism and hostility, it becomes more difficult for a firm performing in such an environment to attain and sustain a competitive advantage; therefore, the ability to effectively combine resources and build new capabilities are perceived primordial for this objective to be attained (Teece et al., 1997).

Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Orientation

In their study on Chinese new state-owned firms, Cai et al. (2018) found that entrepreneurial firms first discover opportunities based on their resources and then exploit the opportunity when integrating external resources that come from their social networks. Similarly, it has been argued by Baron (2002), that the capability of entrepreneurs to accumulate different resources required to initiate any kind of venture is facilitated and encouraged by the entrepreneurs’ SC. In fact, and besides the role of financial capital and other capital attributes, ongoing research in entrepreneurship has shed light on the importance of SC in triggering the ability to engage with effective entrepreneurial activities (Davidsson & Honig, 2003), highlighting on the impact that SC has on entrepreneurial behavior (Davidsson, 2006).

Over the last decades, SC theory has been occupying the scholarly conversation as its discussion has become increasingly complex in management. SC depicts the social interaction and network of relationships that firms position into, in order to get access to useful information and resources. When it’s the case of SMEs, they may face scarcity in internal resources and thus acknowledge the necessity to interact with the external environment. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) defined SC as the sum of the resources that an individual or a social unit has or “may have” due to their network of relationships. Coleman (1988), one of the first scholars to initiate the concept of SC to the literature, has argued that it is similar to human capital and physical capital because it is both productive and defined by its function. Thus, SC can be reflected as a strategic intangible resource due to its uniqueness and invisibility to competitors (Coleman, 1988; Rodrigo-Alarcón et al., 2018; Stam & Elfring, 2008). Indeed, social networks supplement the effects of financial capital, prior experience and education (Bourdieu, 2011; Coleman, 1988). Further to a long debate concerning its operationalization, this concept has been proved and agreed on to be multidimensional, allowing researchers to focus on one or two components of its multidimensionality that they perceive to facilitate or improve EO (Stam & Elfring, 2008) and that serve the scope of their study. The relationship between SC and EO is especially critical in developing economies (Manev et al., 2005). In this context, Foss (2011) elaborated and acknowledged the existence of the “strategic entrepreneurship” field on which opportunity-seeking (considered as the dominant focus of the entrepreneurial field) and advantage-seeking (considered as the dominant focus of the strategic management field) should be cooperatively considered for the benefit of both processes and this is through “organizational networks.”

We build on the identification of Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) who recognized three components of SC; namely structural, relational and cognitive. The structural dimension refers to the connection’s configuration between a firm and others involved in the structure of a network, including the social interaction produced. The relational dimension involves the characteristics of personal relationships that actors have established with time (Granovetter, 1992). Finally, the cognitive dimension of SC represents the resources that offer understandings and meanings within groups (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). It reveals the extent to which actors within a social network understand each other and share the same goals and culture (Chang & Chuang, 2011). Indeed, shared culture refers to the degree to which relationships are ruled by norms of behavior (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005). Besides, these actors are considered valuable resources because they ease the creation of intellectual capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998).

Focussing on the structural aspects of SC, social networks considered as the source of information, helps in sharing information that leads to both proactiveness and creativity. Proactive thinking is a result of the density of this network that takes place through direct interactions (Okafor & Ameh, 2017). In fact, Okafor and Ameh (2017) have stated that proactiveness is somehow related to the strength of the network that builds interaction between the network actors. Ferris et al. (2017) found that SC positively affects risk-taking. Similarly, Rodriguez and Romero (2015) found that structural SC is a determinant of the risk-taking attitude, whereas other researchers concluded that a higher level of structural SC may lead to knowledge redundancy or internal block and blindness (Inkpen & Tsang, 2005; Koka & Prescott, 2002), which reduce both innovativeness and proactiveness. Others researchers found no significant effect of structural SC on EO (e.g., Rodrigo-Alarcón et al., 2018). In the same study conducted by Rodrigo-Alarcón et al. (2018) on the Spanish agri-food industry, it was found that cognitive SC has a positive and significant effect on the EO of the firm. It’s considered to help in growing the entrepreneurs’ efficiency by letting them seize exclusive opportunities (Batjargal, 2003) and thus, increase firm innovation (Doh & Acs, 2010; Jawahar & Nigama, 2011) and proactiveness (Tang, 2010) due to the valuable information it provides. Indeed, cognitive SC plays a crucial role in nurturing and facilitating the transmission of all kinds of transactions, especially when it considers the dispersion of information (Birley, 1985). This is consistent with the “information channels” of Coleman (1988) that network actors keep because of the flow of useful information they grant to them and their role as facilitators for any subsequent action. In this context and under uncertain environmental conditions, the information gathered from social networks enhances opportunity identification (Manev et al., 2005; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000) and exploitation (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). In fact, entrepreneurship entails the profiting of such privileged information to practice decision-making over resources’ usage in favor of markets’ servicing and opportunity exploitation (Foss, 2011). Similarly, Batjargal (2003) argued on the role that SC and generated resources play to assist entrepreneurs in mobilizing resources.

Additional Theoretical Lenses

Self-Efficacy

Since a small business is perceived as the extension of the running individual/CEO (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) and since the entrepreneur that runs the firm has a huge effect on its entrepreneurial posture and overall culture (Becherer & Maurer, 1997) especially when it’s the case of an SME, we perceive a lack of research to see what drives business owners to choose among the entrepreneurial orientations. In this context, Self-Efficacy is considered as a widely employed term when coming to entrepreneurship, explained as the belief of a person in their capabilities and skills to perform a given task or behavior (Ajzen, 1987; Bandura, 1997). It is defined as a self-appraisal of one’s ability to accomplish a task and one’s confidence in possessing the skills needed to perform this task (Garcia et al., 1991). As its name indicates, self-efficacy accelerates the pursuit of goals because it drives a positive view of self. Bandura (1997) argued that an individual’s self-efficacy concerning a given task makes them undertake the task as well as persist in it. Similarly, self-confidence turns out to be considered as self-efficacy only in the case when it’s task-centered, considering an individual with high self-efficacy to be more perseverant and more consistent on the goals they set (McShane & Von Glinow, 2008).

Self-efficacy as a term has been initially proposed in the social learning theory of Bandura (1977, 1989). According to Bandura (1989), an individual with high self-efficacy gets to positively perceive any challenge they face, shows a higher level of interest, commitment and perseverance for a given behavior, and stands back up directly in case of any frustration. Besides, widely dispersed intentional models explain and elaborate the entrepreneurial activity by incorporating the concept of self-efficacy (Krueger et al., 2000) in addition to social and psychological theories (e.g., Ajzen, 1991 [Perceived Behavioral Control]; Boyd & Vozikis, 1994 [Self-Efficacy]; Shapero & Sokol, 1982 [Perceived Feasibility]). In this context, Bandura (1986) has argued that human functioning and action is best explained by incorporating the concept of self-efficacy and theories that have a broad range of applicability. Boyd and Vozikis (1994) argued that self-efficacy doesn’t influence entrepreneurial intentions only, but extends to affect entrepreneurial behavior as well. In their refinement on Bird’s intentional model (1988), Boyd and Vozikis (1994) have suggested that both attitudes and self-efficacy beliefs influence entrepreneurial intentions, whereas self-efficacy moderates the relationship between intentions and the subsequent entrepreneurial behavior. In fact, the individual’s judgment on their self-efficacy in fulfilling the entrepreneurial behavior is what leads to their judgment on the feasibility of this behavior (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994). Therefore, self-efficacy is perceived to play a primordial role in the success or the failure of any venture.

An extension of the self-efficacy construct has been acknowledged through “Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy” (ESE) (Chen et al., 1998). ESE, as described, refers to a person’s own beliefs in their ability to successfully perform and achieve the entrepreneur’s role and tasks. People with high ESE are opportunistic in nature and tend to prioritize opportunities over risk. They believe that their attitude influences what results from their actions, and they don’t count failure as an option (Chen et al., 1998). Self-efficacy as a concept is perceived to be at lower levels in disadvantaged economies where many skilled individuals don’t pursue desired entrepreneurial activities mainly because they lack self-efficacy. This was much emphasized by Krueger and Dickson (1994) who acknowledged the role of self-efficacy in opportunity recognition. Also, in their study on Malay entrepreneurs, Mohd et al. (2014) found that self-efficacy is also related to EO, specifically affecting innovativeness. In turn, Kumar (2007) found a positive correlation between self-efficacy and innovativeness. However, and despite the criticality of self-efficacy in general and in the entrepreneurship field and the subsequent behavior, entrepreneurship scholars didn’t accord much importance to its conceptualization in their scholarly conversations (Krueger et al. 2000).

Subjectivist Theory of Entrepreneurship

There have been many academic attempts that aim to understand what differentiates people who discover opportunities from others who don’t. Venkataraman (1997) argued about the reasons behind these people having the ability to recognize current market problems and gaps and fitting to them suitable offerings, while stating that it all refers to the information that these people have and that in its turn, is based on their own life experiences. Both Covin and Lumpkin (2011) and Wales (2016) linked EO to many theoretical lenses that are found to be triggering it and shaping its scholarly research. One of these theories is the “Subjectivist Theory of Entrepreneurship” proposed by Kor et al. (2007) and that concerns the entrepreneurs themselves.

This theory suggests that the prior experience and knowledge of the entrepreneur are responsible for opportunity recognition and some particular leverage of resources. In addition, this theory is advanced in terms of tackling the existence of EO as a phenomenon while considering both its antecedents and its consequences (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011). Kor et al. (2007) have introduced this theory to focus on the individuals themselves and what concerns their skills and knowledge along with keeping the same focus on the role that subjectivity plays in both the creativity and the discovery processes. In fact, they have emphasized that entrepreneurship can be subjectively perceived and handled. This is because different entrepreneurs have different combinations of knowledge where each combination has its own interpretation. The unique bundle of knowledge and life experiences that the entrepreneur owns will effectively enhance entrepreneurial activity and further affect the competitiveness and growth of its firm. In this context, Shane (2000) argued that the entrepreneur discovers opportunities that are related to their prior knowledge and gathered information, stated as the “knowledge corridor” by Venkataraman (1997). Such information varies among entrepreneurs, being contingent on specific and unique life experiences. Moreover, Kor et al. (2007) have described how someone’s knowledge bundle changes over time, and how this change is accompanied by many disclosures capable of enhancing entrepreneurial discovery. By entrepreneurial discovery, the theorists didn’t mean the discovery of existing opportunities only, but encompassing creativity and opportunity creation, as being a result of interactions between entrepreneurs and different stakeholders. Those entrepreneurs who are driven by creativity don’t settle only on responding to the changes that happen in the market, but instead aim to create change, to innovate and to affect demand (Kor et al., 2007).

One of the main stand-up points of this theory was the focus on the firm-specific knowledge that the entrepreneurs gather and by which they earn a superior quality over managers, key persons and executives of the same firm. This gathered knowledge is mainly tactical, concerns all firm levels, and originates from specific experiences within the firm. Consequently, it seems evident that those entrepreneurs with broad knowledge and experience will be capable of perfectly fitting between an opportunity offered from their surrounding environment and the firm’s insights into its own strengths and weaknesses. In addition to that, the subjectivist theory tackles the team-specific experience and the industry-specific experience as well. The former, as its name indicates, is capable of making the entrepreneur better understood by each member of the team and their attributes. The skills, personality traits and relationships that individuals have with others reflect these personal attributes on which the entrepreneur can rely to assess the overall productivity of the team. Indeed, these attitudes play a major role in the whole team decision-making process and thus affect the firm’s overall performance. Now, moving to the industry-specific experience, the entrepreneur has an interaction with many stakeholders in the industry such as customers, suppliers, lenders and many others, and on which they can build an industry-specific knowledge affecting their subjective perception on different opportunities accordingly. In fact, the ability to recognize and evaluate opportunities highly depends on industry-related knowledge and experiences, as this theory suggests. An opportunity discovery can be well achieved when information on industry actors, behavioral patterns of customers as well as unmet needs is gathered. The subjective perception of the individual entrepreneur is consequently built upon this information, and favors the growth and prosperity of the firm.

Entrepreneurial Dominant Logic (DL)

The concept of Dominant Logic (DL) was first introduced by Prahalad and Bettis (1986) and defined as the managers’ approach of conceptualizing the business and deciding on resource distribution. The cognitive orientation of top decision-makers reflects the way they engage in strategic decisions in their organization. This cognitive orientation is a resultant of the individual’s previous experience and knowledge. The concept of entrepreneurial DL has been later elaborated by Meyer and Heppard (2000) to be considered as a more employed concept when connecting to EO research and its scholarly conversation (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011). In their book, Meyer and Heppard (2000) presented the idea of entrepreneurship as a DL that drives the creation of firms’ entrepreneurial strategies. They perceived the entrepreneurial DL as a stimulus for the continuous information search and filtering in order to bring on innovations to the firm and further profit from these innovations.

In their later work, thought on DL has rotated, and thus Bettis and Prahalad (1995) redefined DL as a level of strategic analysis and an information filter through which strategists consider important data and information. This filter has control over what these strategists find important or not, since they select data that fit to their cognitive filter mechanism. Considering this, and as per the conceptualization of DL described above, any current or future structural and strategic decisions made by managers will be based on their DL which is the only factor capable of diminishing some choices or to motivate undertaking others accordingly. Along with this, Covin and Lumpkin (2011) have attributed the difference between EO patterns in firms performing in similar environments to DL considering its high influence on the entrepreneurial posture of a given firm and its ability to differentiate between one firm and another. In this context, and within a study performed on Mexican manufacturing ventures, it was found that DL mediates the EO-performance relationship, and risk-taking, aggressiveness and innovativeness had the highest correlations with DL (Campos et al., 2012).

Organizational Culture and Structure

With the aim of not narrowing the discussion of internal factors on entrepreneurs and decision-makers only, though they are the ones having the most influence on the firm’s strategic orientation and its entrepreneurial posture, especially when it considers the case of SMEs, one must consider the organizational context that differentiates a firm from its rivals and that can be considered as a valuable type of intangible resources. In this context, “Culture” as a term has its roots in the anthropology discipline. When this term is used, anthropologists usually aim to show the uniqueness of a certain community and the extent to which it differs from other communities in its behavior transmitted to the subsequent generations. However, four decades ago, “culture” as a term started being attributed to the “organization” term to then be combined as “organizational culture” that is mostly employed to differ an organization from others. In fact, the rewarded behaviors in an organization as well as the most valued manners belong to the organizational culture. This culture is transferred from one generation of employees to another and is defined as the set of shared values, attitudes and business principles that outline accepted behaviors in a given firm. Therefore, within the aim to be entrepreneurially active, a firm must hold a positive culture that favors proactiveness and innovativeness. Defending this point of view, Covin and Slevin (1991) within their investigation on internal variables, have talked about both the culture and the structure of an organization and how both can affect the firm’s entrepreneurial posture by enhancing its innovativeness, its proactive search for opportunities and its risk-taking tendency. Moreover, in their study on the factors that produce EO, Fayolle et al. (2010) proposed corporate culture to enhance the firm’s EO. Within this same perspective, Abdullah et al. (2017) argued that organizational culture defines the behavior of the organization through the influence it has on the attitudes and behaviors of its members. Indeed, the thoughts and actions of an organization’s members are shaped by the existing corporate culture and the strength of this culture is measured by the extent to which the organization’s members believe in it and manifest it. In fact, it has been perceived that when relationships and interactions between the organization’s members are fostered, many dimensions of EO get affected, specifically innovativeness and risk-taking (Miller, 2011).

Also, Denison (1990) has shown in a study that the culture of an organization has four main characteristics which are: involvement, consistency, adaptability and mission, and it’s through these characteristics that the organizational culture has implications on the efficiency of the firm. Involvement is considered as the level to which members of an organization have a say in the decision-making process. This involvement diffuses a sense of responsibility and is capable of fostering the firm’s actors’ creativity and innovativeness since they start to feel that they have a real impact on the organization and its goals’ achievement process (Abdullah et al., 2017). Similarly, Schein (1983) perceived entrepreneurial leaders as the ones that set the corporate culture in an organization through promoting autonomy between members and units and stimulating innovation. Consistent however, is the level to which those members accept the essential and fundamental values of the organization. By accepting the values, members get more integrated into the organization and start to coordinate activities which in turn has implications on the organization’s effectiveness. Adaptability (having common characteristics of DCs as per the researcher’s judgment) is how an organization leads to internal changes as a response to environmental changes. Adaptability is a tool for organizations to serve customers with the best value possible by making necessary changes internally. Mission, and as its name indicates, is defined as the most important purpose of why the organization exists. Therefore, the organization’s mission should be well-defined in order to facilitate the relationship with the external environment and thus structure an effective future vision (Abdullah et al., 2017).

Moving to “Organizational Structure”, this is more about how communication and authority relationships are settled within the organization (Covin & Slevin, 1991) where differences in structure exist, defined as either organic or mechanistic (Covin & Slevin, 1991). In both cases, the structure influences the entrepreneurial activity and posture of the firm. However, flexibility in the structure of the firm is needed for it to take decisions promptly especially in response to its rivals (Covin & Slevin, 1988). So there is always a call for a suitable organizational structure (flattening hierarchies and assigning authority as per Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) that includes mainly an easy flow of information and communication with the minimum number of layers possible. Miller (2011) added that many contingency theorists in the literature have asserted that a looser and more organic structure is capable of enhancing innovation.

Eventually, one must know that when it’s a mechanistic structure, authority has higher prominence than expertise in the firm, and information concerning the business is only accessible to picked top-notch individuals inside the organization. In this kind of structure, job descriptions are very rigid and procedures of operations are formalized. Instead, when it’s an organic structure, expertise has a higher prominence than authority, and information is easily accessed and shared among different members of the organization; also existing procedures have little importance when confronted with a goal to be attained. In this context, decentralized decision-making is considered as an important asset for a firm. Miller and Friesen (1982) argued about the relationship between structural variables and entrepreneurial firms’ innovativeness. In their turn, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) argued that when the decision-making is decentralized, the performance of the firm is enhanced, especially when this firm displays EO. In contrast, bureaucracy has been perceived differently by another group of scholars, who have perceived routines to positively serve innovation, and proactiveness of the firm seen as their ability to gather and monitor resources.

Conclusion

EO has occupied the scholarly conversation within the entrepreneurship domain for decades (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011). Therefore, and for the construct research to advance, this chapter acknowledges the gaps within the EO theory and adds valuable theoretical and practical ramifications to the body of knowledge of EO. This review has followed the suggestions of many scholars and aimed to bring on to the academic conversation what has been thought of as a promising path in the EO research that concerns its antecedents. Thus, according to the previous emphasis put on different firm attributes in facilitating exhibition of entrepreneurial activity and strategic action, in this chapter, we exhibited the role of firm resources, DCs, the conditions of a firm’s network and some additional internal factors that consider both the firm and the entrepreneur in fostering EO within SMEs. In addition, as this review has considered the context of SMEs operating in emerging economies, it raises the hope of motivating further exploration of EO in this context, seeing the low incorporation of such frameworks within entrepreneurship studies.

On a theoretical level, this study is based those rare ones that tackled the EO construct-antecedents-and-consequences-relationship and illustrated a theoretical framework based on this exploration. On a practical level, the analysis of the literature review highlighted some recommendations to SMEs to reconsider the dispositions of EO aspects within their firms and reconfigure what triggers their attitudes and behaviors. However, other recommendations are addressed to the parties concerned with formulating strategies that foster the existence of SMEs and enhance their capabilities. They must tailor their strategies and policies to meet the needs of SMEs and ease their environment, specifically those competing in both national and regional economies. As for the recommendations addressed to scholars, this chapter inspires further exploration in investigating the EO construct and the context where it occurs. Also, a recommendation maintains on proposing a longitudinal study design in EO where the relationship between the dimensions of the construct and firm performance can be tracked over time and among different stages of the firm’s development.

References

Abdullah, S., Musa, C. I., & Azis, M. (2017). The Effect of Organizational Culture on Entrepreneurship Characteristics and Competitive Advantage of Small and Medium Catering Enterprises in Makassar. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(2), 409–414.

Ajzen, I. (1987). Attitudes, Traits, and Actions: Dispositional Prediction of Behavior in Personality and Social Psychology. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 1–63.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Aldrich, H. Z., & Zimmer, C. C. (1986). Entrepreneurship through Social Networks. Ballinger. Cambridge, MA.

Aloulou, W. (2002). Entrepreneurial Orientation Diagnosis in SMEs: Some Conceptual and Methodological Dimensions. Entrepreneurship Research in Europe; Specificities and Prospectives, INPG-ESISAR Valence (France).

Aloulou, W., & Fayolle, A. (2005). A Conceptual Approach of Entrepreneurial Orientation within Small Business Context. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 13(1), 21–45.

Alvarez, S. A., & Busenitz, L. W. (2001). The Entrepreneurship of Resource-based Theory. Journal of Management, 27(6), 755–775.

Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2009). What are Dynamic Capabilities and are They a Useful Construct in Strategic Management? International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 29–49.

Anderson, B. S., Kreiser, P. M., Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Eshima, Y. (2015). Reconceptualizing Entrepreneurial Orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10), 1579–1596.

Audretsch, D. B. (2002). The Dynamic Role of Small Firms: Evidence from the US. Small Business Economics, 18(1–3), 13–40.

Audretsch, D. B. (2007). The Entrepreneurial Society. Oxford University Press.

Awang, A., Khalid, S. A., Yusof, A. A., Kassim, K. M., Ismail, M., Zain, R. S., & Madar, A. R. S. (2009). Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance Relations of Malaysian Bumiputera SMEs: The Impact of Some Perceived Environmental Factors. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(9), 84–96.

Bakar, L. J. A., & Ahmad, H. (2010). Assessing the Relationship between Firm Resources and Product Innovation Performance. Business Process Management Journal, 16(3), 420–435.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1986). The Explanatory and Predictive Scope of Self-Efficacy Theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Macmillan.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Strategic Factor Markets: Expectations, Luck, and Business Strategy. Management Science, 32(10), 1231–1241.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baron, R. A. (2002). OB and Entrepreneurship: The Reciprocal Benefits of Closer Conceptual Links. Research in Organizational Behavior, 24, 225–269.

Batjargal, B. (2003). Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Performance in Russia: A Longitudinal Study. Organization Studies, 24(4), 535–556.

Becherer, R. C., & Maurer, J. G. (1997). The Moderating Effect of Environmental Variables on the Entrepreneurial and Marketing Orientation of Entrepreneur-Led Firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(1), 47–58.

Bettis, R. A., & Prahalad, C. K. (1995). The Dominant Logic: Retrospective and Extension. Strategic Management Journal, 16(1), 5–14.

Bhuian, S. N., Menguc, B., & Bell, S. J. (2005). Just Entrepreneurial Enough: The Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurship on the Relationship between Market Orientation and Performance. Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 9–17.

Birley, S. (1985). The Role of Networks in the Entrepreneurial Process. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 107–117.

Birley, S., & Norburn, D. (1985). Small Vs. Large Companies: The Entrepreneurial Conundrum. Journal of Business Strategy, 6(1), 81–87.

Bourdieu, P. (2011). The Forms of Capital. (1986). Cultural Theory: An Anthology, 1, 81–93.

Bouri, A., Breij, M., Diop, M., Kempner, R., Klinger, B., & Stevenson, K. (2011). Report on Support to SMEs in Developing Countries through Financial Intermediaries. Dalberg, November.

Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The Influence of Self-efficacy on the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4), 63–77.

Brockhaus, R. H., Sr. (1980). Risk Taking Propensity of Entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509–520.

Cai, L., Peng, X., & Wang, L. (2018). The Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Entrepreneurial Behaviour: The Case of New State-Owned Firms in the New Energy Automobile Industry in an Emerging Economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 135, 112–120.

Campos, H. M., la Parra, J. P. N. D., & Parellada, F. S. (2012). The Entrepreneurial Orientation-Dominant Logic-Performance Relationship in New Ventures: An Exploratory Quantitative Study. BAR-Brazilian Administration Review, 9(SPE), 60–77.

Caner, S. (2010, April). The Role of Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Economic Development. In HSE Conference.

Carmeli, A., & Tishler, A. (2004). The Relationships between Intangible Organizational Elements and Organizational Performance. Strategic Management Journal, 25(13), 1257–1278.

Chandler, G. N., & Hanks, S. H. (1994). Market Attractiveness, Resource-based Capabilities, Venture Strategies, and Venture Performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(4), 331–349.

Chang, H. H., & Chuang, S. S. (2011). Social Capital and Individual Motivations on Knowledge Sharing: Participant Involvement as a Moderator. Information & Management, 48(1), 9–18.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy Distinguish Entrepreneurs from Managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

Chen, C. N., Tzeng, L. C., Ou, W. M., & Chang, K. T. (2007). The Relationship Among Docial Capital, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Organizational Resources and Entrepreneurial Performance for New Ventures. Contemporary Management Research, 3(3), 213–232.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Conner, K. R. (1991). A Historical Comparison of Resource-based Theory and Five Schools of Thought within Industrial Organization Economics: Do We have a New Theory of the Firm? Journal of Management, 17(1), 121–154.

Coulthard, M. (2007). The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Firm Performance and the Potential Influence of Relational Dynamism. Journal of Global Business & Technology, 3(1), 29–39.

Covin, J. G., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2011). Entrepreneurial Orientation Theory and Research: Reflections on a Needed Construct. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 855–872.

Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate Entrepreneurship and the Pursuit of Competitive Advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 47–63.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1988). The Influence of Organization Structure on the Utility of an Entrepreneurial Top Management Style. Journal of Management Studies, 25(3), 217–234.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–26.

Covin, J. G., Slevin, D. P., & Schultz, R. L. (1994). Implementing Strategic Missions: Effective Strategic, Structural and Tactical Choices. Journal of Management Studies, 31(4), 481–506.

Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The Measurement of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677–702.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2000). A Resource-based Theory of Strategic Alliances. Journal of Management, 26(1), 31–61.

Davidsson, P. (2006). Nascent Entrepreneurship: Empirical Studies and Developments. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 1–76.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The Role of Social and Human Capital among Nascent Entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331.

De Clercq, D., Dimov, D., & Thongpapanl, N. (2013). Organizational Social Capital, Formalization, and Internal Knowledge Sharing in Entrepreneurial Orientation Formation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 505–537.

Denison, D. R. (1990). Corporate Culture and Organizational Effectiveness. John Wiley & Sons.

Dess, G. G., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2005). The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Stimulating Effective Corporate Entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1), 147–156.

Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T., & Eisner, A. B. (2008). Strategic Management—Creating Competitive Advantage (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Doh, S., & Acs, Z. J. (2010). Innovation and Social Capital: A Cross-Country Investigation. Industry and Innovation, 17(3), 241–262.

Dollinger, M. J. (1999). Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources. Prentice-Hall.

Drucker, P. F. (1985). The Discipline of Innovation. Harvard Business Review, 63(3), 67–72.

Farmer, S. M., Yao, X., & Kung-Mcintyre, K. (2011). The Behavioral Impact of Entrepreneur Identity Aspiration and Prior Entrepreneurial Experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(2), 245–273.

Fayolle, A., Basso, O., & Bouchard, V. (2010). Three Levels of Culture and Firms’ Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Research Agenda. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(7–8), 707–730.

Ferrier, W. J. (2001). Navigating the Competitive Landscape: The Drivers and Consequences of Competitive Aggressiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 858–877.

Ferris, S. P., Javakhadze, D., & Rajkovic, T. (2017). CEO Social Capital, Risk-Taking and Corporate Policies. Journal of Corporate Finance, 47, 46–71.

Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Marzocchi, G. L., & Sobrero, M. (2012). The Determinants of Corporate Entrepreneurial Intention within Small and Newly Established Firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 387–414.

Foss, N. J. (2011). Entrepreneurship in the Context of the Resource-based View of the Firm. Perspectives in Entrepreneurship: a critical approach, Palgrave Macmillan, UK.

Frese, M., Brantjes, A., & Hoorn, R. (2002). Psychological Success Factors of Small Scale Businesses in Namibia: The Roles of Strategy Process, Entrepreneurial Orientation and the Environment. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(3), 259–282.

Galbreath, J., & Galvin, P. (2008). Firm Factors, Industry Structure and Performance Variation: New Empirical Evidence to a Classic Debate. Journal of Business Research, 61(2), 109–117.

Garcia, T., McKeachie, W. J., Pintrich, P. R., & Smith, D. A. (1991). A Manual for the Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, School of Education.

George, B. A., & Marino, L. (2011). The Epistemology of Entrepreneurial Orientation: Conceptual Formation, Modeling, and Operationalization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 989–1024.

Granovetter, M. (1992). Problems of Explanation in Economic Sociology. In Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The Resource-based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135.

Grimm, C. M., Lee, H., & Smith, K. G. (Eds.). (2006). Strategy as Action: Competitive Dynamics and Competitive Advantage. Oxford University Press.

Hambrick, D. (1987). Top Management Teams: Key to Strategic Success. California Management Review, 30, 88–108.

Hameed, I., & Ali, B. (2011). Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Entrepreneurial Management and Environmental Dynamism on Firms’ Financial Performance. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 3(2), 101–114.

Haugh, H. (2005). A Research Agenda for Social Entrepreneurship. Social Enterprise Journal, 1(1), 1–12.

Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D. A., & McMullen, J. S. (2009). An Opportunity for Me? The Role of Resources in Opportunity Evaluation Decisions. Journal of Management Studies, 46(3), 337–361.

Helfat, C. E., & Martin, J. A. (2015). Dynamic Managerial Capabilities: Review and Assessment of Managerial Impact on Strategic Change. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1281–1312.

Henderson, J. (2002). Building the Rural Economy with High-growth Entrepreneurs. Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 87(3), 45–75.

Hill, H. (2001). Small and Medium Enterprises in Indonesia: Old Policy Challenges for a New Administration. Asian Survey, 41(2), 248–270.

Hughes, M., & Morgan, R. E. (2007). Deconstructing the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance at the Embryonic Stage of Firm Growth. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(5), 651–661.

Hult, G. T. M., Hurley, R. F., & Knight, G. A. (2004). Innovativeness: Its Antecedents and Impact on Business Performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(5), 429–438.

Inkpen, A. C., & Tsang, E. W. (2005). Social Capital, Networks, and Knowledge Transfer. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 146–165.

Irava, W., & Moores, K. (2010). Resources Supporting Entrepreneurial Orientation in Multigenerational Family Firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 2(3/4), 222–245.