Abstract

As its marketing strategy to attract top international students, Canada adopts a discourse of Canadian exceptionalism to promote itself as a country with outstanding quality of education, high standard of living, safety, clean environment, wide-open spaces, low tuition fees, and affordable living expenses. Canadian exceptionalism is also evident in its rhetoric about Canada’s multiculturalism policies which present the country as an open and culturally diverse nation. Canadian exceptionalism as a social imaginary also constructs Canada different from its southern neighbor as a peaceful and tolerant country without racism. In this chapter, we contest the discourse of Canadian exceptionalism as a myth in contrast to the actual policies and practices of the internationalization of Canadian higher education. In particular, we focus on the perspectives and lived experiences of international students as they adapt to a new educational system in Canada.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Canadian exceptionalism

- Internationalization of higher education

- International student

- Internationalization of the curriculum

- Racism

- Canada

Fueled by globalization, the internationalization of higher education in Canada is happening at a rapid pace. One manifestation of such development is the increasing enrollment of international students. As its marketing strategy to attract top international students, Canada adopts a discourse of Canadian exceptionalism to promote itself as an immigrant country and a land of opportunities with a vast territory and rich resources. More specifically, EduCanada (2021) identifies a list of reasons for international students to study in Canada, including outstanding quality of education, high standard of living, safety, clean environment, wide-open spaces, low tuition fees, and affortable living expenses. Canadian exceptionalism is also evident in its rhetoric about Canada’s multiculturalism policies which present the country as an open and culturally diverse nation. Canadian exceptionalism as a social imaginary also constructs Canada different from its southern neighbor as a peaceful and tolerant country without racism.

In this chapter, we contest the discourse of Canadian exceptionalism as a myth in contrast to the actual policies and practices of the internationalization of Canadian higher education. In particular, we focus on the perspectives and lived experiences of international students as they adapt to a new educational system in Canada. To be more specific, we analyze how internationalization policies at a university in Western Canada were interpreted and experienced by international students. Based on policy analysis and interviews with international students, our findings reveal that international students have multiple understandings of internationalization and view internationalization as a positive experience for academic and personal growth. Findings also indicated several persistent problems, including a neoliberal approach that treats internationalization as revenue generating and branding strategy, limited internationalization of the curriculum, difficulty in making friends with local students, and racial discrimination. The findings have important implications, not only for Canada but also to countries which share similar contexts and challenges, for providing appropriate levels of support for international students and building an internationally inclusive campus, where cross-cultural learning is encouraged and global citizenship are nurtured.

Rationales of Internationalization

As a contested term, internationalization can mean many different things to different people. For some people, it means a series of international activities (e.g., academic mobility of students and faculty), international linkages and partnerships, and new international academic programs and research initiatives, while for others it means the delivery of education to other countries through satellite programs (Guo & Chase, 2011; Knight, 2004). De Wit et al. (2015) define internationalization as “the intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of post-secondary education, in order to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society” (p. 29). This definition places a focus on intentionality and broadens internationalization from mobility to include curriculum and learning outcomes. Another term that is often used interchangeably with internationalization is globalization. There is a general consensus among scholars that internationalization is not globalization. They are seen as related, but at the same time very different processes. According to Knight (2003), “internationalization is changing the world of education and globalization is changing the world of internationalization” (p. 3).

Having defined the term, it is necessary to understand the rationales of internationalization. De Wit et al. (2015) named four key rationales for internationalization: political, economic, sociocultural, and academic. In the twentieth century, and in particular after the Second World War, there was an increased focus on international cooperation and exchange in higher education. Although peace and mutual understanding were the declared driving rationales, “national security and foreign policy were the real reasons” behind the expansion of internationalization (de Wit & Merkx, 2012, p. 49). From the second half of the 1990s onwards, the principle driving force for internationalization has shifted from political to economic. International students and international activities were used by many institutions in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States as revenue generation (Kelly, 2000; Teichler, 2010). In addition to international student recruitment, preparing graduates for the global competitive labor market and attracting top talent for the knowledge economy have become important pillars of the internationalization of higher education over the past decade (de Wit et al., 2015). Socioculturally, internationalization was based on the hope that international mobility could enhance mutual understanding (Khoo, 2011). Academically, internationalization was perceived as a means to improve “the quality of teaching and learning and prepare students to live and work in a globalized world” (de Wit et al., 2015, p. 28). It has been promoted as a way to achieve international academic standards for branding purposes and foster international collaboration in research and knowledge production.

Unlike European priorities that were driven by economic and political considerations (Elliott, 1998), the rationales for the internationalization of Canadian higher education focused on sociocultural and academic aspects: preparing graduates who are internationally knowledgeable and interculturally competent global citizens and enhancing scholarship for interdependence between Canadian and international students in addition to generating income for universities (Knight, 2000). Knight also found the three rationales for having international students at Canadian institutions were to “integrate domestic and international students in and out of the classroom, to increase the institutions’ profiles and contacts in target countries, and third, to generate revenue for the institution” (Knight, 2000, p. 53).

Internationalization of the Curriculum

Internationalization of the curriculum aims to incorporate “international, intercultural, and/or global dimensions into the content of the curriculum as well as the learning outcomes, assessment tasks, teaching methods, and support services of a program of study” (Leask, 2009, p. 209). Three approaches are often used by faculty members to internationalize the content of the curriculum, namely, the add-on approach, the curricula infusion approach, and the transformation approach (Bond, 2003). The add-on approach, as the name implies, often involves adding on a reading or an assignment to the existing course content and leaves the main body of the course untouched and unquestioned. This is the easiest approach with a narrow focus and limited impact. The second is perhaps the most widely used approach infusing the curriculum with international content in the selection of course materials and integration of student experience into learning activities. It requires much more preparation on the part of the faculty member and often involves the broader participation of faculty and students. The transformation approach is more difficult to undertake, but has the potential to change people. This approach, Bond argues, enables students to move between two or more worldviews and requires a shift in the way we understand the world. When it is realized, it yields genuine reform in the curriculum.

The second component in internationalization of the curriculum involves internationalizing teaching strategies and classroom experiences which best support the learning objectives of an internationalized curriculum. Unfortunately, literature documenting such practices remains nearly nonexistent (Bond, 2003). Drawing from other studies that are relevant to internationalization of the curriculum, Bond offers the following observations. She suggests that it is important for faculty members to develop a classroom climate of respect and trust; communicate to students what is important in a course; get to know your students; respect and value students’ knowledge and experience; and use contextualized and cooperative learning strategies to enhance participations. She emphasizes the importance of collaborating with colleagues and using campus resources to ensure effective practices. She also reminds us that students with international and intercultural experience are untapped resources. She further cautions us not to separate international students from other students. Finally, Bond argues, there is no predetermined starting point for internationalizing the curriculum, nor any single way to internationalize the curriculum. We have to take into consideration the context, including class size, subject matter, and the international and intercultural experiences of participants. Furthermore, in the process of internationalizing the curriculum, faculty members play a significant role in determining its success.

The Identity Crisis of Internationalization

Reflecting on the internationalization over the last decade, internationalization has suffered from an identity crisis. As Knight (2014) lamented, “internationalization has become a catch-all phrase used to describe anything and everything remotely linked to the global, intercultural or international dimensions of higher education and is thus losing its way” (p. 76). In response to this identity crisis of internationalization, Knight calls for an examination of the fundamental values underpinning internationalization.

One identity crisis related to the fundamental values underpinning internationalization pertains to the economic approach as a principle driving force of internationalization. The literature on the internationalization of higher education presents two major discourses: market-driven (i.e., related to fostering economic performance and competiveness) and ethically driven (i.e., related to charitable concerns for enhancing the quality of life of disadvantaged students) discourses (Khoo, 2011). Financial crises are driving profit-seeking policies of internationalization in higher education in many countries. Critics highlight the exploitation of international students as being treated like “cash cows.” As such, internationalization is seen as a reflection of “a complex, chaotic and unpredictable edubusiness, whose prioritization of the financial ‘bottom line’ has supplanted clear normative educational and, indeed, overtly ideological intents” (Luke, 2010, p. 44). With respect to the second discourse, internationalization is believed to have the ethical responsibility to engage with alternative agendas such as human rights and building a global civil society (Kaldor, 2003). Recent literature, driven by critical scholars such as Abdi and Shultz (2008) and Andreotti (2013), also indicates that concepts expressed in internationalization policies and initiatives such as governments’ and institutions’ social responsibility, transnational mobility of students, and students’ interculturality that are associated with global citizenship have come to combine both market and ethical influences to enhance students’ learning.

Second, critical scholars question internationalization as the dominant global imaginary and its colonial myth of Western ontological and epistemological supremacy (Guo et al., 2021; Ng, 2012; Stein & Andreotti, 2016). As Stein and Andreotti note, the dominant global imaginary of Western supremacy is produced and reproduced not only by and in the West, but also by many across the globe. Duplicating Western policies without consideration of the local context in many universities in Asia raises the question of “whether internationalization becomes recolonization in the postmodern era” (Ng, 2012, p. 451). To illustrate with an example, Guo et al. (2021) interrogate the unidirectional orientation of internationalization as understood and practiced in Chinese higher education as “Westernization” and “Englishization.” In the context of China, the internalization of the superiority of Western sources of knowledge has become a crucial element of a hidden curriculum. In this process, the domination of English is closely associated with the superiority of Western knowledge. As Yang (2016) reminded us, Westernization is not new. Since China’s encounters with the West in the nineteenth century, repeated defeats led China to feel disadvantaged in its relations with the West. So the West came to China with enormous prestige. Furthermore, the use of English as a medium of instruction (EMI) promotes the hegemony of English as a global language in China (Guo & Beckett, 2007). As such, the need to internationalize the university is interpreted to mean to “Englishize” the university and their programs (Rose & McKinley, 2018). Marginson (2006, p. 25) made a similar point in arguing that the English language universities “exercise a special power, expressed as cultural colonization” and the displacement of the intellectual traditions other languages support. As a symbol of internationalization, English has become a gatekeeper for internationalization; only those with high scores in IELTS and TOEFL are selected for studying abroad. Hence, the “Englishization-equals-internationalization ideology” is pervasive in the Chinese education policy, curricula, and use of EMI (Guo et al., 2021). In light of this, the authors call for an approach to de-Westernize the ideological underpinnings of colonial relations of rule and Eurocentric tendencies influencing the current ideological moorings of internationalization and practices of Chinese higher education.

The Canadian Context

In 2014, the Government of Canada (2014) launched its first federal international education strategy, with a vision to “become the twenty-first century leader in international education in order to attract top talent and prepare our citizens for the global marketplace, thereby providing key building blocks for our future prosperity” (p. 6). With a neoliberal agenda driven by economic motives, international education was identified as one of the 22 priority sectors to help Canada enhance its economic prosperity and global competitiveness in a knowledge-based economy. As part of the international education strategy, attracting international students at all levels of education became the top priority with a goal to double the number of international students by 2022 (from the level of 2011). In fact, Canada’s federal policy on internationalization has always had a strong focus on international students as a market. Since the 1980s, Canadian universities have been utilizing the revenue from international student tuition to ameliorate financial shortfalls resulting from marked declines in government funding for higher education (Cudmore, 2005; Knight, 2008).

The 2014 strategy reinforced the narrative of international students as a source of revenue for universities and for the country, stating that “international students in Canada provide immediate and significant economic benefits to Canadians in every region of the country” (Government of Canada, 2014, p. 7). Citing a commissioned study by Kunin (2012), it reported that in 2012 international students’ tuition, books, accommodation, meals, transportation, and discretionary spending was estimated to be about $8.4 billion per year, which in turn generated more than $455 million in government tax revenues. Furthermore, international students are also seen as “a future source of skilled labour” which is critical to ensuring Canada’s national prosperity in an increasingly competitive global environment (Government of Canada, 2014, p. 12). It is evident that internationalization is primarily seen in terms of its economic benefits to Canada.

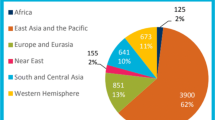

As a result of its aggressive promotion, Canada’s international student population has tripled over the past decade to 642,000 in 2019 which ranked Canada the third most popular destination after the US and Australia (El-Assal, 2020). The five countries from which the largest number of international students came in descending order of number were: India, China, South Korea, France, and Vietnam. Yet, when international students arrive on Canadian campuses, they face a number of challenges including isolation, alienation, marginalization, and low self-esteem. In the following section, we will examine how international students experience the internationalization of higher education in Canada.

Contesting Canadian Exceptionalism in the Internationalization of Higher Education

In responding to Knight’s (2014) call for scholars and institutions to rethink the fundamental values of internationalization, in this section, we contest the discourse of Canadian exceptionalism in the internationalization of Canadian higher education. We focus on internationalization at one university and international students’ experiences of internationalization at this institution in Western Canada. The university launched its International Strategy in 2013, in which internationalization formed one of the priorities in the university’s long-term strategic policy visions. A key target of internationalization goals was to increase the number of international students on campus to 10% of the undergraduate population by 2016. In the following discussion, we analyze how internationalization policies and practices at this university were interpreted and experienced by international students. Based on interviews with 26 international students from nine countries, our study shows that international students have multiple understandings of internationalization. Their views of internationalization and lived experiences contest the mythical narrative of Canadian exceptionalism in higher education.

Multiple Understandings of Internationalization

Our findings demonstrate international students’ multiple understandings of internationalization. In the interviews, most participants referred to internationalization as the increasing enrollment of international students in Canadian institutions of higher education and their international experiences. International students reported the challenge and difficulty of defining internationalization. The fact that they had mixed understandings of internationalization is not necessarily a problem, considering that the literature applies different definitions. In general, they referred to internationalization as student mobility and research collaborations between institutions. One student from China commented, “To me, it means coming to Canada to study” (Yumi). For many participants, there was a direct link between their understanding of internationalization and their personal experiences of studying in Canada. For some participants, internationalization offered an opportunity for them to develop a global vision. These aspects of internationalization identified by the participants were similar to academic and sociocultural principles of internationalization discussed by Knight (2004) and de Wit et al. (2015). But for others, internationalization was about particular ways of thinking about the world or about westernization as illustrated by one student from Taiwan.

Most participants felt internationalization had a positive effect on them in offering opportunities for development of research interests, independence in learning, and personal growth. The participants enjoyed acquiring information, research training, hands-on experience, and analytical skill. Most participants reported they enjoyed the academic freedom in Canada. For example, all four Chinese students in computer science said they had more choices in their course selection from software, hardware, and network, three parts that were separated in China. Mike was one of the undergraduate students sponsored by the China Scholarship Council (CSC). As a fourth year student, he was doing a required final project and noted that studying in Canada, particularly learning how to do a literature review, helped him develop his research interest. He also commented on the development of independence in learning as an international student.

Other students illustrated the development of their hands-on ability by having more opportunities to conduct experiments in the lab and making equipment themselves. For example, Kimo in Geography noted: “If we need to use tubes [in the lab], we need to buy pipes, cut and assemble them.” Most students reported that they not only developed a strong sense of independence in learning but also increased their self-confidence and developed stronger communication skills. For example, James, a Chinese student in Geophysics, noted his positive character change from being shy to not being afraid to talk to new people. Other students commented they matured as a result of their independent life experiences in another culture, such as learning how to budget for grocery shopping and learning how to cook. Similarly, Krystal from China in Computer Science noted her growing maturity and her open-mindedness as a result of her international experience.

Internationalization, Revenue Generation, and Branding

In this study, international students critiqued the university’s goal of internationalization for revenue generating and branding purposes. Access to international mobility is often limited to students who have earned scholarships. Most participants of our study primarily represent two groups of elites in the source country, the socioeconomic elite who are mostly self-funded and the educated elite who are funded by government scholarships. Participants in this study reported that the average international student at the university paid $21,932 CAD in tuition fees—a number that was three times higher than what domestic students paid. On average, international students spent about $40,000 on tuition and living expenses together annually. In light of this, most participants perceived that the university used international students for revenue generation, an “internationalization as marketization model” critiqued by Luke (2010, p. 49). This is in part due to declining government funding for higher education that has formed the context for the internationalization of universities in many Western countries (Marginson, 2006). For example, between 2000/01 and 2012/13, the proportion of university revenues from provincial governments was decreased from 43 to 40% in Canada (CAUT, 2015). Many of the Chinese students in the study represented the educated elite, receiving scholarships from the China Scholarship Council. They had a grade point average above 85% in all academic subjects at their domestic university in China and passed the interview in English. In some cases, they represented the brightest students from their home universities. Given this context, some participants critiqued the university’s desire to capitalize on their talents and use international students to raise its profile nationally and internationally. This aligns with one of the university’s rationales for internationalization: to position the university as a global intellectual hub and to increase international presence and impact. Khoo (2011) suggests that financial pressures push universities toward marketized, competitive, and unethical interpretations of internationalization whereas ethical development policies and programs for mutual learning and benefit are eroded. Most participants in this study were critical about the university’s tendency to view international students as “cash cows” (Stein & Andreotti, 2016) and its emphasis on raising revenue and branding purposes ahead of the care and education of international students.

Little Internationalization of the Curriculum

At the policy level, the university emphasized the internationalization of the curriculum as illustrated in its 2013 International Strategy. In practice, however, international students reported that they felt there were few teaching and learning resources that were related to their experiences as noted by Jane in Education from China who stated, “I don’t see there are many materials on my international experience. They [instructors] seldom talk about things happening in China. I think only in X course I experienced a lot because the instructor is from a similar background” (Jane, Education, China). Similarly, Alice, an international student from Brazil who studied film commented that in the courses that she took, mostly American and European film history was taught, but Brazil was only mentioned in passing. Even when there were some teaching and learning resources that were related to their experiences, these resources appeared to portray their countries as backward. Amy in English mentioned that in her drama course, she was shocked to see how Korean surgery was portrayed in a video shown by the instructor. Mery was also critical that Iran was portrayed as both backward and violent in students’ discussion in class.

Students’ experiences show the contradictions between the internationalization of the curriculum across policy and practice. At the policy level, internationalization of the curriculum aims for “the incorporation of international, intercultural, and/or global dimensions into the content of the curriculum as well as the learning outcomes, assessment tasks, teaching methods, and support services of a program of study” (Leask, 2009, p. 209). In practice, from the international students’ perspectives, the internationalization of the curriculum is limited. For example, our findings revealed that students rarely encountered materials that reflected their experiences, and when they did, the materials tended to be dated or skewed. As Haigh (2009) argues, “today, although many classes emerge as a cosmopolitan mix, curricula remain Western” (p. 272). Some students felt that the effect of this lack of international content may be negative, in that it reinforces prejudices and stereotypes. These findings provide evidence for Leask’s (2015) critique that “one common misconception about internationalization of the curriculum is that the recruitment of international students will result in an internationalized curriculum for all students” (Leask, 2015, p. 11).

Difficulty in Developing Friendships with Local Students

One of the goals of the internationalization policy at this university is to increase international representation among the study body on campus. For some time, it was a commonly held belief that increasing the diversity of the student body would lead to understanding and friendships between international and local students (Leask, 2015). Unfortunately, this is not something that happens naturally. When international students came to the Canadian campus, particularly for those from Asia and the Middle East, they indicated that they were not well-received and often felt alienated. The international students in this study reported that it was difficult for them to make friends with local students. Lily, a student from China who spent four years in Canada pursuing her undergraduate degree, stated that while she could develop working relationships with her classmates over one semester, it was difficult to become friends with them. She explained that university students in China usually stay in the same cohort for four years, attending the same courses together each semester, making it easier to become friends with classmates. In Canada, however, as the students are different in each class, she noted that it was difficult to be in touch with the same classmates consistently, making it difficult to develop friendships with local students. Lily added another reason, explaining that “local students don’t have patience. They don’t want to understand international students” Liwang concurred. Similarly, she noted a lack of understanding among local students in that they “never experience what we experience, learning a different culture and language.”

A few students identified their low English language proficiency as the main reason for difficulties in becoming friends with local students. Other students indicated that even without language issues, it was still difficult to make friends with local students. One student who studied in English major noted the lack of opportunity for her to interact with local students: “I don’t even see any Canadian around me except in class…after class they just leave, not much opportunity to talk to them” (Amy, English, South Korea). Many students mentioned that they did not share the same interests. For example, Tyler, an indigenous American from Alaska, reported he enjoys going to the Native Centre at the university whereas his Canadian peers like to play hockey. Alex, a Chinese student in Engineering, said some local students like to go to the bar and he does not like the pub environment. Another reason why it was difficult for them to make friends with host university students was related to dealing with different life styles. James in Geophysics from China was surprised by the amount of partying and drinking involved in undergraduate life. He did not partake in his roommates’ usual activities and suggested this could be one of the reasons he felt excluded from friendship. He further expressed discontent dealing with a roommate who did not cleanup, which was another barrier to friendship.

The above discussion reveals that many factors influence engagement between international and domestic students, including linguistic, academic, and social factors. The participants in our study reported English language and communication challenges as major obstacles to forming meaningful relationships with students of the host society. Difficulty with English language is also reported in other studies (Aune et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2015). In addition to language barrier, many international students felt there is a lack of common interests or different life styles between them and local students. The international students in this study also reported there is a lack of opportunities for interaction between these two groups. Similarly, Zhang and Brunton’s (2007) study also found that 55% of the 140 Chinese students they surveyed in New Zealand “were dissatisfied with the availability of opportunities to make New Zealand friends” (p. 132). Sometimes, the international students in this study also sensed unwillingness from local students to connect. This study shows that the mere presence of international students on campus does not necessarily lead to interactions and intercultural understanding between local and international students.

Racism and Racial Discrimination

At the policy level, most institutional internationalization efforts tend to neutralize existing racial hierarchies in the realm of education and beyond (Stein et al., 2016). In reality, some international students in this study had to deal with deep-rooted racism from their peers and people in the local community in the form of verbal attacks, including swearing and being told to return to their home country. Feelings of hurt were exacerbated in classrooms where international students felt excluded or ignored by other students, as illustrated by Liwang who felt she was left out of students’ study groups because of who she is. Lily, on the other hand, felt even though she was physically included by other students in study groups, her ideas were ignored due to her English accent. To Krystal in Computer Science, people in Canada appear to be friendly, but may discriminate against other people based on race. She stated, “I actually feel that on the surface, people here will not discriminate against you; they are very friendly. If you have any difficulty, they will help you. But there is deep-rooted racism.” Mery, an international student from Iran, had to deal with racism in the local community. She was ridiculed because of the hijab she was wearing in part-time employment. From her perspective, the choice to wear a hijab remains poorly understood in Canada, partly due to Islamophobia, dislike of or prejudice against Islam or Muslims. Mery stated that it is important to guard against equating difference in dress with cultural backwardness, similar to Zine’s argument (Zine, 2000).

This finding is consistent with results of Lee and Rice’s (2007) and Brown and Jones’ (2013) studies. Lee and Rice, in their study of the experiences of international students at a US university, found that students from Asia, Africa, South America, and the Middle East experienced neo-racism in the form of verbal insults and direct confrontation. Brown and Jones, in their study of international graduate students at a university in the UK, found that one third of 153 surveyed experienced racism, including verbal assaults. The limited receptiveness of the local community may contribute to the sense of alienation among international students. More recently, since the outbreak of COVID-19, racism and ethnic discrimination resurfaces and proliferates in many countries on the globe. In Canada, for example, there has been a surge in racism and xenophobia during the global pandemic toward Asian international students, particularly those of Chinese descent (Guo & Guo, 2021). De Wit et al. (2015, p. 29) identified the main purpose for internationalization as “to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society.” It seems that from our findings, the university is not doing enough to enhance the quality of education and research for all students. Universities appear as unprepared as international students in handling the current cross-cultural encounters.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we contest the discourse of Canadian exceptionalism in the internationalization of Canadian higher education by exploring the perspectives and lived experiences of international students in Canada. Contrary to the rhetoric that Canada is an open, welcoming, and racism-free society, students’ actual experiences testify that the Canadian exceptionalist discourse is a myth. The results of the study reveal several discrepancies between internationalization policies and practices at the institutional level and the lived experiences of international students. In its current approach to internalizing Canadian higher education, several persistent problems are identified. One pertains to treating internationalization as business opportunities and marketing strategies. Second, in internationalization of the curriculum, the current practice privileges Eurocentric perspectives as some international students did not see teaching materials that reflected their experiences. Third, despite a false narrative of Canada as a culturally tolerant nation, students’ experiences reveal difficulties of integrating into the Canadian academic environment with challenges ranging from making friends with domestic students to racial discrimination. Although there is an interest in bringing in international students to internationalize Canadian campuses, in reality there has been a lack of support to help international students successfully integrate into Canadian academic environments.

From these findings, we beg the following questions: Are we too complacent? Is Canada truly exceptional? What are the limits of the discourse of Canadian exceptionalism? With respect to internationalization, what changes need to be made to maximize the learning experience of international student in Canada? The findings suggest that we must engage in critical deep reflections as to how we treat our international students. We argue for more ethically oriented policies and practices of internationalization in higher education as opposed to profit-seeking orientation. First, host institutions need to be cognizant of how they put the internationalized curriculum into action. An internationalized curriculum demands that educators view international students not only as knowledge consumers but also as knowledge producers. This means that the knowledge and linguistic resources that international students bring need to be valued, and the internationalized curriculum needs to connect to international students’ lived experiences. The findings also have important implications for host institutions in providing appropriate levels of support to help international students with their transition and adaptation. Support for international students has to move beyond the usual one-time welcome orientation. It is important to combine students’ academic needs with their social and cultural needs. Furthermore, urgent actions need to be taken to eliminate racism and racial discrimination on Canadian campus and to recognize and embrace cultural differences and diversity. It is important to note that integrating international students requires collective efforts of university administrators, faculty, staff, and students in building an internationally inclusive campus, where cross-cultural learning is encouraged. If institutions of higher education are serious about internationalizing their campuses, it is essential that they provide necessary support to assist international students with their transition and integration. Like Canada, many countries in the world (e.g., Australia, Japan, UK, US) are experiencing increasing enrollment of international students who also encounter numerous challenges similar to those reported in this chapter in adapting to new academic environment in their host societies. While many universities and colleges are searching for solution to help international students with their adaptation, it is hoped that lessons learned from the Canadian experience will serve as catalyst for other countries to examine exceptionalism from their own contexts so that positive changes can take place.

References

Abdi, A. A., & Shultz, L. (2008). Continuities of racism and inclusive citizenship: Framing global citizenship and human rights education. In A. A. Abdi & S. Guo (Eds.), Education and social development: Global issues and analyses (pp. 25–36). Sense Publishers.

Aune, R. K., Hendreickson, B., & Rosen, D. R. (2011). An analysis of friendship networks, social connectedness, homesickness, and satisfaction levels of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 281–295.

Andreotti, V. D. O. (Ed.). (2013). The political economy of global citizenship education. Routledge.

Bond, S. (2003). Untapped resources, internationalization of the curriculum and classroom experience: A selected literature review. Canadian Bureau for International Education.

Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2013). Encounters with racism and the international student experience. Studies in Higher Education, 38(7), 1–16.

Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT). (2015). CAUT Education Review. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from https://www.caut.ca/docs/default-source/education-review/caut---education-review-(spring-2015).pdf?sfvrsn=8

Cudmore, G. (2005). Globalization, internationalization, and the recruitment of international students in higher education, and in the Ontario Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 35(1), 37–60.

de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L., & Egron-Polak, E. (2015). Internationalization of higher education. Brussels: European Union Parliament Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

de Wit, H., & Merkx, G. (2012). The history of internationalisation of higher education. In D. Deardorff, H. de Wit, J. Heyl, & T. Adams (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of international higher education (pp. 43–59). SAGE.

EduCanada. (2021). Top reasons to study in Canada. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from https://www.educanada.ca/why-canada-pourquoi/reasons-raisons.aspx?lang=eng

El-Assal, K. (2020). 642,000 international students: Canada now ranks 3rd globally in foreign student attraction. CIC News: The Voice of Canadian Immigration. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from https://www.cicnews.com/2020/02/642000-international-students-canada-now-ranks-3rd-globally-in-foreign-student-attraction-0213763.html#gs.g781rr

Elliott, D. (1998). Internationalization in British higher education: Policy perspectives. In S. Peter (Ed.), The globalization of higher education (pp. 32–43). Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Government of Canada. (2014). Canada’s international education strategy: Harnessing our knowledge advantage to drive innovation and prosperity. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from https://www.international.gc.ca/global-markets-marches-mondiaux/assets/pdfs/overview-apercu-eng.pdf

Guo, S., & Chase, M. (2011). Internationalisation of higher education: Integrating international students into Canadian academic environment. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(3), 305–318.

Guo, S., & Guo, Y. (2021). Combating racism and xenophobia in Canada: Toward pandemic anti-racism education in post-COVID-19. Beijing Review of International Education, 3(2), 187–211. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from https://doi.org/10.1163/25902539-03020004

Guo, Y., & Beckett, G. H. (2007). The hegemony of English as a global language: Reclaiming local knowledge and culture in China. Convergence, 40(1–2), 117–132.

Guo, Y., Guo, S., Yochim, L., & Liu, X. (2021). Internationalization of Chinese higher education: Is it Westernization? Journal of Studies in International Education, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315321990745

Haigh, M. (2009). Fostering cross-cultural empathy with non-Western curricular structures. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2), 271–284.

Kaldor, M. (2003). Global civil society – an answer to war? Polity.

Kelly, P. (2000). Internationalizing the curriculum: For profit or planet? In S. Inayatullah & J. Gidley (Eds.), The university in transformation: Global perspectives on the futures on the university (pp. 162–172). Greenwood Publishing.

Khoo, S. M. (2011). Ethical globalisation or privileged internationalisation? Exploring global citizenship and internationalisation in Irish and Canadian universities. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(3–4), 337–353.

Knight, J. (2000). Process and promise: The AUCC report on internationalization at Canadian universities. Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

Knight, J. (2003). Updating definition of internationalisation. International Higher Education, 33, 2–3. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2003.33.7391

Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5–31.

Knight, J. (2008). The role of cross-border education in the debate on education as a public good and private commodity. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 1(2), 174–187.

Knight, J. (2014). Is internationalisation of higher education having an identity crisis? In A. Maldonado-Maldonado & M. R. Bassett (Eds.), The forefront of international higher education: A Festschrift in Honor of Philip G. Altbach (pp. 75–87). Springer Netherlands.

Kunin, R. (2012). Economic impact of international education in Canada—An update: Final report. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from http://www.international.gc.ca/education/assets/pdfs/economic_impact_en.pdf

Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2), 205–221.

Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the curriculum. Routledge.

Lee, J. J., & Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. Higher Education, 53(3), 381–409.

Luke, A. (2010). Educating the ‘other’ standpoint and internationalization of higher education. In V. Carpentier & E. Unterhaler (Eds.), Global inequalities in higher education: Whose interests are you serving? (pp. 1–25). Palgrave/Macmillan.

Marginson, S. (2006). Dynamics of national and global competition in higher education. Higher Education, 52(1), 1–39.

Ng, S. W. (2012). Rethinking the mission of internationalization of higher education in the Asia-Pacific region. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 42(3), 439–459.

Rose, H., & McKinley, J. (2018). Japan’s English-medium instruction initiatives and the globalization of higher education. High Education, 75, 111–129.

Scott, C., Safdar, S, Trilokekar, R., Masri, A. (2015). International students as ‘ideal immigrants’ in Canada: A disconnect between policy makers’ assumptions and the lived experiences of international students. Comparative and International Education, 43(3), Article 5.

Stein, S., & Andreotti, V. D. O. (2016). Cash, charity, or competition: International students and the global imaginary. Higher Education, 72, 225–239.

Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Bruce, J., & Suša, R. (2016). Towards different conversations about the internationalization of higher education. Comparative and International Education, 45(1), Article 2. Retrieved March 30, 2021 from: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cie-eci/vol45/iss1/2

Teichler, U. (2010). Internationalising higher education: Debates and changes in Europe. In D. Mattheou (Ed.), Changing educational landscapes. Educational policies, schooling systems and higher education – a comparative perspective (pp. 263–283). Springer.

Yang, R. (2016). Internationalization of higher education in China: An overview. In S. Guo & Y. Guo (Eds.), Spotlight on China: Chinese education in the globalized world (pp. 35–49). Sense Publishers.

Zhang, Z., & Brunton, M. (2007). Differences in living and learning: Chinese international students in New Zealand. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11, 124–140.

Zine, J. (2000). Redefining resistance: Towards an Islamic subculture in schools. Race Ethnicity and Education, 3(3), 293–316.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Guo, S., Guo, Y. (2022). Contesting Canadian Exceptionalism in the Internationalization of Higher Education: A Critical Perspective. In: Abdi, A.A., Misiaszek, G.W. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook on Critical Theories of Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86343-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86343-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86342-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86343-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)