Abstract

Non-heterosexual and trans youth face violence and threat of it in many forms in their schools. Part of this violence is based on the assumption or knowledge of these young people’s sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression. In the chapter will be analysed the responses and stories of non-heterosexual and trans youth, and the data is a survey produced by the Finnish lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex human rights organisation Seta and Youth Research Network. The survey data consists 1861 responses, out of which 994 were non-heterosexual women, 380 non-heterosexual men, 404 transmasculine respondents and 83 transfeminine respondents. This data is analysed intersectionally based on sexual orientation, gender identity and the presumed gender at birth. The usefulness and problems in using the concepts of homophobia and transphobia is discussed, when analysing the stories on violence against trans and non-heterosexual youth in educational contexts. They leave out of focus a part of violence, which is linked to and or based on heteronormative practises. They are rather psychological and medical concepts, which often focus on individual behaviour and emotions, and they do not always take into account the larger societal issues and contexts.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Young lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) youth can face various kinds of violence, such as physical, psychological or mental, verbal, sexual or religious/spiritual violence, or threats of violence in their lives. This can limit their ability to be themselves and express their gender and sexuality the way they want, in schools and elsewhere (see Blackburn, 2012; DePalma & Atkinson, 2009). In this chapter I will analyse the experiences of violence encountered by non-heterosexual and trans youth in Finland.Footnote 1 I focus particularly on their experiences of violence in schools, and I will ask how sexuality, gender and the norms around them are linked to the violence they experience.

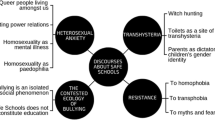

When violence towards LGBT people is analysed, the focus is often on homo- or transphobic violence, and the rest of the violence they face is not concentrated on so much. In this chapter, I criticise this practice and also analyse the violence that cannot be clearly described as homo- or transphobic, or as violence motivated by a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity or how they express gender. In my analysis, I utilise the point of view of gender and sexuality. I will also discuss the problems with using homophobia or transphobia as a concept in analysing violence towards LGBT people. The conceptualisation is meaningful, when analysing gender- and sexuality-based or related violence, while with the concepts we open and limit what we will see, and that will affect how we look at the reality and act against violence (see Hearn, 1998).

By non-heterosexual, I mean a qualitative term used to describe a person, who has sexual emotions or practices directed at their own gender, or a self-definition that refers to these emotions or practices (such as lesbian, gay, or bisexual). Trans refers to a person who challenges the gendered norms and expectations in that the gender they were designated with at birth contradicts the gender they identify with or express. In this chapter, by transmasculine is meant a person who was assigned female at birth, and with transfeminine is meant a person who was assigned male at birth, but who defined themselves later as trans or otherwise questioned their expected gender identity.

I use the concept of heteronormativity to refer to a way of thinking or reacting that refuses to see diversity in sexual orientation and gender, and that considers a certain way of expressing or experiencing gender and sexuality to be better than another (Lehtonen, 2003). This includes normative heterosexuality and gender normativity, according to which only women and men are considered to exist in the world. Men are supposed to be masculine in the “right” way and women feminine in the “right” way. According to heteronormative thinking, gender groups are internally homogeneous and each other’s opposites, and hierarchical in that men and maleness are considered more valuable than women and femaleness. The heterosexual maleness of men and the heterosexual femaleness of women are emphasised and are understood to have biological origins (cisnormativity). Either the existence of other sexualities or genders is denied, or they are considered worse than the options based on heterosexuality and a dualistic gender system (see also Rossi, 2006; Martinsson & Reimers, 2008; Butler, 1990).

An undesirable, even silent place for non-heterosexuality and trans experience thus forms in a community where a person is normatively expected or hoped to be heterosexual (normative heterosexuality) and to realise behaviours that are in line with gender norms (gender normativity) (see Lehtonen, 2003). Heteronormativity is not the same around the world, but constructed differently based on time, location and culture, and it is connected to other normativities (related to race, age, class and so on). I also use the concepts of homo- and transphobia, when I specifically aim to describe the individual-level acts, such as hate speech, violence, or reactions, which are motivated by sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. I see both of them as being explainable by heteronormativity.

The data for the analysis comes from the research project “Wellbeing of rainbow youth”. This was a joint project of the Finnish lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) human right organisation Seta and the Finnish Youth Research Network (Alanko, 2013; Taavetti, 2015). I was a member of the group that planned the survey questionnaire and commented on the reports, and was able to use the data for my own research. My focus is on non-heterosexual and trans youth under 30 years old (N = 1861). The non-heterosexual respondents group (N = 1374) was clearly larger than the trans respondents group (N = 487). I divided respondents among these groups based on the interpretation of gender at the time of their birth, to make it possible to analyse what gender has to do with their experiences. In these diverse groups, people have many kinds of gendered identities and express gender in various ways, but they were typically brought up according to the assumption of their gender at the time of their birth. The four groups in my analysis are: (1) non-heterosexual men (N = 380), (2) non-heterosexual women (N = 994), (3) transmasculine youth (N = 404), and (4) transfeminine youth (N = 83).

There were several open questions about violence, to which participants of the survey could respond with their stories or answers. After replying to questions about experiences of different types of violence (physical, mental, sexual and spiritual), respondents had the chance to write freely about their experiences. I use the same terms in the analysis as were used in the survey. These terms were not defined for the respondents, so they could have understood them differently. Mental violence could be translated as psychological violence as well, and many young respondents described acts of non-physical verbal violence and harassment when talking about mental violence. Spiritual violence was referred to as violence related to religion, or violence in a religious context. In the question, they were asked to tell about their experiences (if they wanted to) and of how they survived and what consequences there had been. There were altogether 502 stories or answers to questions.Footnote 2 More stories were told about physical and mental violence compared to sexual and spiritual violence. For this chapter, I selected a few of the stories in which violence in schools were discussed.

The survey was collected from all willing to take part, and it is not a statistically representative sample. It is however the largest ever survey of young non-heterosexual and trans youth in Finland, and also the largest ever survey of trans persons in the country. I used mixed methods, analysing the survey data with descriptive statistics and the stories using content analysis. I analysed how non-heterosexual and trans youth answered the survey questions on different type of violence, and whether sexual orientation and gender identity/expression had anything to do with how they replied. I analysed gendered and sexualised aspects of the stories that the participants told about school violence. I asked how heteronormative culture is linked to or expressed in their stories of violence. I analysed the data intersectionally based on age, sexual orientation, gender identity and the presumed gender at birth (see Cho et al., 2013; McCall, 2005).

First, I will discuss the concepts of homophobia, transphobia, heteronormativity and related terms, which are used in analysing violence against LGBT people. Then I will give an overview of the Finnish context in relation to violence against LGBT people, and particularly youth in the school context. Then I will explain what was discovered in the survey data. After that, I analyse young people’s stories of their experiences of violence in schools. In the conclusion, I come back to the conceptual discussion and ask how our research choices limit or open up opportunities to understand violence towards LGBT youth, and what could be done differently both in research and in the education system.

Homophobic, Transphobic and Heteronormative Violence

The term homophobia was used in the 1960s in the United States in various ways, but George Weinberg’s Society and the Healthy Homosexual in 1972 made the concept better known (see Weinberg, 1972; Fone, 2000; Sears, 1997). Afterwards there have been many terms used in relation to violence against LGBT people: gay/faggot/queer bashing, anti-gay/lesbian violence, gay-hatred, sexual terrorism, sexual orientation victimisation, bias/hate/prejudice motivated crime/violence (Tiby, 1999; Murray, 2009). A typical homophobic incident in many studies is a case in which one or more (drunk) men beat up a gay man in public place, and often men are found to face greater homophobia than women. The violence linked to homophobia was thus constructed in a male-centred fashion. Homophobia has been used to describe violence against LGB and sometimes T (trans) people, though there has been a need to find a more specifically focused terms to analyse phobia against LBT people: and lesbophobia, biphobia and transphobia have been used (see Hutchins & Kaahumanu, 1991; Denny, 1994; Sears, 1997).Footnote 3 Even heterophobia has been used, in analysing feminist discourses in which men and heterosexuality are constructed as enemies (Patai, 1998). Often, violence against LGBT persons has been analysed using the concept violence based on/motivated by person’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity/expression. In research where this has been the case, the topic has typically been violence against LGBT people, and not against heterosexual and cis-gendered people, even if the concepts include this possibility.

The concept of homophobia has been criticised by many (see among others Sedgwick 1990; Adam, 1998; Wickberg, 2000; Lehtonen, 2002; O’Brien, 2008; Murray, 2009; Smith et al. 2012). It is seen as too individualistic, psychological and medical. The focus in defining the term lay originally in negative emotions, such as hatred and (irrational) fears, of a person or people towards (known or presumed) LGBT persons (self or others). The structural and societal problems or negative attitudes and practices that caused or created space for homophobic reactions and emotions were then neglected. Later the concept was used in many ways to define negative attitudes towards LGBT rights; discriminatory policies, institutions or even countries or continents (Africa as homophobic, see Jungar & Peltonen, 2016) have been labelled as homophobic, if these have maintained practices that are seen as problematic in relation to LGBT issues.

The many ways of using the concept of homophobia and the different connections given to the term (it has been explained by gender-based violence or sexism) have created a need to invent new expressions around the term. There is talk of homophobias, in the plural, for example when researchers seek to emphasize the various sources of fear or hate of LGBT people (Fone, 2000), or when they analyse how homophobia is constructed differently in various cultural contexts (Murray, 2009). Different levels of homophobia have been noted to exist: personal, interpersonal, institutional and cultural (Blumenfeld, 1992). Hate towards trans persons has been seen to be constructed from genderism, transphobia and gender bashing (Willoughby et al., 2011).

Some people, mainly in Western liberal discourse, see homophobia as a key issue alongside racism and sexism (Wickberg, 2000). However, the other two are more societal concepts from the start, and they include the possibility of unequal attitudes in anybody, though they are also often used when underprivileged groups are targeted, such as black people and women (Kulick, 2009). Homophobia is also seen to be used in a universalistic way, so that the human subject of the story is seen as constant and unchanged regardless of the time or location (Wickberg, 2000). Thus it fails to take into account racialised, classed, gendered and other social hierarchies (Manalansan, 2009; O’Brien, 2008).

Homophobia as a research concept has been used in problematic ways without being located within larger societal contexts, which has resulted in weak research designs, and that has been one reason to use the term heterosexism instead (Smith et al., 2012). Heterosexism became a more popular concept among feminist writing in the 1970s and 1980s. Often it meant an addition to sexism, and was used to speak of the privileged position of heterosexuality or heterosexual couples, sex, or persons compared to other possibilities. Sometimes the concept also included, by definition, negative attitudes towards or fears of homosexuality, or was used to cover both normative heterosexuality and sexism. Viewing heterosexism as an aspect of a broader ideology of gender and sexuality, Gregory Herek (1990, 2004) distinguishes between cultural (worldview) and psychological (internalisation of this worldview) heterosexism. Heterosexism and its related concepts (compulsory heterosexuality, heteropatriarchy, heterosexual contract, heterosexual matrix, heterosexual hegemony, heteronormativity etc.) were developed to understand norms, ideologies, institutional practises and constructions around sexuality and gender (see Butler, 1990; Lloyd, 2013). Often these aim to describe broader societal aspects. They do not often fit well in analysis of the emotions, such as fear or hate, towards LGBT people in incidents of violence, unless the emotions are understood to be based on the cultural context and formed within heterosexist discourse (see Ahmed, 2014).

My own position on homophobia, transphobia, and other gendered and sexualised violence experienced by LGBT people is based on the acknowledgment that there are no perfect terms to fully describe every aspect of the various kinds of violence faced by non-heterosexual and trans people. In this chapter I will both critically use the concepts of homophobia and transphobia in a strict sense, relating to violence motivated by person’s known or presumed sexual orientation or gender identity/expression, and enlarge the analysis on other types of violence related to heteronormativity. I define heteronormative violence as violence that is argued with or influenced by a heteronormative understanding of gender and sexuality or that aims to maintain heteronormativity. Homo- and transphobic violence are specific aspects of heteronormative violence.

Violence Against Non-heterosexual and Trans Youth in Schools in Finland

Finland is a Nordic welfare state, with a public and free education system that emphasises equality, at least on the level of education politics and documents (Kjaran & Lehtonen, 2017). The Equality and Non-Discrimination Act was renewed in 2014 (and came into force in January 2016), to strengthen equality and non-discrimination in education, workplaces and elsewhere. Accordingly, all schools and educational institutions must have a plan to address gender equality as well as anti-discrimination (also against discrimination based on sexual orientation). The framework of this renewed legislation covers trans people well (gender identity and expression). Many educational institutions do not fully comply with the law and have not changed their relevant policies. This planning should include ideas and plans on how to support trans and non-heterosexual students, and on how to prevent bullying, harassment and unfair treatment of LGBT students. Non-violence policies and programmes exist, but LGBT youth are often not taken into account at all, or only marginally.

The national research survey on violence against children has not covered violence from the point of view of sexual orientation or gender identity/expression in Finland. Based on the survey in 2013, most crimes reported to police were acts of physical violence (75%), and in these cases most of the victims were boys (70%) (Humppi, 2008; Fagerlund et al., 2014). These were typically physical violence cases in which boys faced violence from other boys in schools or other youth settings. Sexual violence was also reported to police (20% of all reported cases), and the victims in these crimes were mostly girls (87%). The national youth crime survey did not ask for respondents’ sexual orientation or gender-identity/expression, but hate crimes were analysed (Näsi, 2016). Ten percent of respondents had experienced a hate crime, and of these 9% reported that the motivation for the crime was sexual orientation. Studies covering victims’ experiences of violence in general do not cover the issues of sexual orientation and gender identity/expression, so there is very little information on the frequency of violence faced by LGBT people, and particularly of homo- and transphobic violence (Peura et al., 2009). The issue of violence against LGBT people is still little researched in Finland (see also Lehtonen, 2007a, b; Hiitola et al. 2005; Telakivi et al., 2019).

In 2017, the national school health survey finally began to ask respondents their sexual orientation and gender identity, and about 5% of respondents were found to be trans and about 10% non-heterosexual (out of tens of thousands of respondents altogether).Footnote 4 It was found that non-heterosexual youth experienced violence significantly more often in upper secondary education compared to heterosexual youth (Luopa et al., 2017; Ikonen, 2019). Violence was experienced more often in vocational upper secondary education than in general upper secondary education and non-heterosexual boys experienced violence more frequently than girls. In the 2017 survey, 16% of non-heterosexual boys faced bullying at least once a week in vocational education, which is clearly more often than heterosexual boys (3%) or non-heterosexual girls (4%) in vocational education, or non-heterosexual boys (7%) in general upper secondary education. Non-heterosexual boys had experienced the threat of physical school violence in vocational (27%) slightly more often than in general upper secondary education (22%), but over 10% points more often than heterosexual boys (14% and 12%) (Luopa et al., 2017).Footnote 5 Trans respondents (N = 1140) in general upper secondary education experienced school violence clearly more often (32%) than cisgender respondents (11%); and they also experienced gender-based violence radically more often (21%) than cisgender students (2%) (Ruuska, 2019). Trans respondents had been bullied on a weekly basis in basic education (23%, N = 3552) more often than in vocational (15%, N = 706) or in general (6%, N = 1122) upper secondary education (Ikonen, 2019).Footnote 6 Trans respondents experienced this kind of violence clearly more often than non-heterosexual youth.

The issues of violence are covered in some surveys and other research projects, which have focused on LGBT issues, but in these the topic of violence has been just one aspect.Footnote 7 In the Finnish research homophobia and transphobia are not typically used as terms to define the violence faced by LGBT people, but it is analysed with more neutral terms such as violence against LGBT or violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression. In the school environment, homophobic name-calling and bullying based on gender non-conformity have been acknowledged as typical phenomena in many school cultures in several studies (Lehtonen, 2002, 2010, 2014; Lehtonen et al., 2014). Even in the research on homophobic name-calling in schools, the term homophobia was not used, but in Finnish language it is covered by a local term, “homottelu” (substantive) or “homotella” (verb) meaning to call someone a “homo” (Lehtonen, 2002).

During recent years studies have been performed by the European Union, which have also covered the experiences of Finnish respondents on violence (FRA, 2009, 2014a, b). The main survey study revealed that the majority (68%) of Finnish respondents had heard negative comments or insults at school caused by being LGBT. In the EU, every fourth LGBT person had faced violence during the last 5 years and 10% during the last year. Almost half of the Finnish respondents (48%) reported that the last incident of violence during the last 12 months had happened partially or completely because they were perceived to be LGBT. Gay men and trans people reported this more often than lesbians and bisexuals. So it seems that almost half of the violence experienced by LGBT people in Finland is hate-based. Out of Finnish LGBT respondents, 18% reported that they had faced hate-motivated harassment during the last year. Police were not informed about the hate crimes people faced: the last hate-motivated crime experienced by Finnish LGBT people was reported to police by only 1% of the respondents. Less than one in six (16%) of the most recent incidents of hate-motivated violence that had occurred to respondents in the last 12 months were brought to the attention of the police. This does not automatically lead the police to record these crimes in general, or specifically as hate-based. The “Being Trans” survey found that 4% of Finnish trans respondents had faced hate-motivated violence and 20% harassment based on their being trans (or presumed trans) during the last 12 months (FRA, 2014b).

Only three research surveys have covered experiences of violence on LGBT youth (Huotari et al., 2011; Kankkunen et al., 2011, Alanko, 2013). A survey on LGBT students’ experiences in upper secondary education discovered that 63% of the respondents had observed mental violence or bullying based on belonging to sexual or gender minorities in school, and that 36% of the respondents had been bullied themselves (Huotari et al., 2011). Gender minority youth had experienced bullying more often than sexual minority youth, and it was more typical in vocational than general upper secondary education. Another report published by the Ministry of Interior Affairs discovered that over half of sexual minority youth had experienced name-calling related to sexual orientation (Kankkunen et al., 2011). A survey on LGBT youth, which is also used as data in this chapter, found out non-heterosexual youth had experienced physical, mental and sexual violence and different kinds of harassment more often than heterosexual youth, and trans youth more often than cis-gendered youth who responded to the survey (Alanko, 2013).

Violence Experienced by Non-heterosexual and Trans Youth

A majority of the young non-heterosexual and trans youth who took part in the survey have experienced some kind of negative behaviour towards them, and not only during their life in general but also during the last year. Most of them live in social and cultural settings where they are likely to meet people who act in violent or otherwise insulting ways. The settings can be of many kinds, but the violent or unjustifiable behaviour often happens at home within the family, at school, within intimate relationships, and in other settings such as on the street and in other public places, bars and night clubs, hobbies and religious groups. These are often places where young people are supposed to spent most of their time and where they should be able to feel safe.

In the survey, non-heterosexual and trans youth were asked if they had experienced physical, mental, sexual or spiritual violence. Trans respondents experienced all four forms of violence more often than non-heterosexual respondents. Non-heterosexual men and transfeminine respondents experienced physical, mental and spiritual violence more often than non-heterosexual women and transmasculine respondents, but non-heterosexual women and transmasculine respondents experienced sexual violence more often. Gender seems to be an important factor in several ways. Boys and young men, as well as those who are thought to be boys or young men (most of the transfeminine respondents over at least a certain period of their life), are more likely to face violence than girls and women. Girls and women (and the ones who were seen to be girls or women such as transmasculine respondents) experienced sexual violence more often than boys and men. So, in this sense, the pattern for non-heterosexual and trans youth is similar to those for other people in the Finnish culture. Gender non-confirming youth seem to be at greater risk of facing violence, which might explain the higher levels of experiences of violence among the trans respondents. I also argue that it is more difficult for presumed boys and men to bend the gender norms than for presumed girls and women, and that might explain the result of transfeminine respondents’ higher levels of experiences of violence compared to transmasculine respondents.

The most typical form of violence was mental violence, then physical violence (see Table 10.1). Sexual and spiritual violence were not that common, but many had experiences of those as well.

These figures covered the respondents’ entire lifetimes, but there was also a question that asked respondents about their experiences of violent or other negative behaviour towards them during the last year (see Table 10.2).

The most typical forms of negative behaviour faced by non-heterosexual and trans youth during the last year were insulting name-calling and teasing and exclusion from groups, which might be practices typical in the school and other educational settings. A minority of the respondents reported other types of negative behaviour. Trans respondents reported negative behaviour more often than non-heterosexual respondents. There were differences and similarities between respondent groups. Non-heterosexual women and transmasculine respondents were more likely to report being left outside friendship circles compared to non-heterosexual men and transfeminine respondents. It could be that, even if boys (or presumed boys) are left outside the circles of other boys, they may find girls to befriend, while the reverse is often not the case for girls (or presumed girls) in similar situations. Most of the other negative behaviour was reported more often by non-heterosexual men and transfeminine respondents than by non-heterosexual women and transmasculine respondents. They faced insulting name-calling (non-heterosexual men) and insulting behaviour via mobiles or Internet (transfeminine respondents) clearly more often.

Even if the figures above can be analysed through gendered and sexual lenses, the experiences are not necessarily linked to the sexual orientation, gender identity or expression of the respondents. In fact, most of the violence faced by non-heterosexual and trans respondents was not reported by them to be linked to their sexual orientation, or gender identity/expression (see Table 10.3).

There were several differences in the types of violence and the respondent group in the meaning of sexual orientation and/or gender identity/expression to their experiences of violence. The majority of the experiences of physical violence were not linked to these, but the majority of spiritual violence was. Non-heterosexual men and transfeminine respondents felt clearly more often than non-heterosexual women and transmasculine respondents that sexual orientation and/or gender identity/expression were meaningful factors in the violence they had faced. One important difference, for example, lies in physical violence: while 40% of non-heterosexual men felt that it was linked to their sexual orientation or gender expression, only 15% out of non-heterosexual women felt so. The majority of non-heterosexual women saw no connection with these factors in all other forms of violence except the spiritual. Trans respondents felt more often than non-heterosexual respondents that these factors were meaningful in explaining the violence or negative behaviour that they had faced.

School as Context of Heteronormative Violence

In the earlier section, I demonstrated that most of the violence experienced by LGBT youth in Finland is neither homophobic nor transphobic. The results were not directly linked to the school context, but I will argue that the same point can be made in the context of school violence. It is relevant to analyse why non-heterosexual and trans youth also face violence or the threat of violence clearly more often than heterosexual and cisgender youth in the school context, even if the majority of the violence they experience is not homophobic or transphobic. (see School health survey, Luopa et al., 2017; Ikonen, 2019).

In the school context, a similar pattern exists as in the overall situation concerning violence experienced by LGBT youth. Non-heterosexual men (27%) faced physical school violence more often than non-heterosexual women (17%) in basic education. Transfeminine respondents (33%) faced physical school violence more often than transmasculine respondents (14%) in upper secondary and tertiary education (16–25 year olds). Contrary to the school health survey (Ikonen, 2019), trans youth in the data I used seemed to experience violence more typically in upper secondary education than in basic education. I explained this by the possibility that trans respondents in my survey data had come out as trans persons in their school at a later stage, in upper secondary education (Lehtonen, 2014). Presumed men are more often at risk of physical violence in schools than presumed women, particularly those who do not fit in the gendered norms (Lehtonen, 2002, 2018). Sexual violence was also more common in the school context for non-heterosexual women (than men) and for transmasculine respondents (than transfeminine). Presumed women face sexual violence more often than presumed men. Trans youth experienced violence and other problems more often than non-heterosexual youth. They faced weekly or daily experiences of violence (7.5%) more commonly than non-heterosexual youth (5%).

A central point in understanding the violence experienced by LGBT youth is gender and the norms around it. If you do not fit into the heteronormative culture with its gender-normative and cisnormative understanding of gender and normative heterosexuality, you are likely to be excluded and left without friends and support networks, and you are likely to feel outside and not fit in with the group. I would argue that this is a key to understanding the differences of experiences of violence between non-heterosexual and heterosexual youth, between trans and cisgender youth, and between (presumed) girls and boys. Homophobic and transphobic motivations only partially explain these differences, but normative culture around sexuality and gender are still meaningful factors in explaining the rest of the differences. It is easier to choose as a victim of threat of violence, or physical and mental violence, a person who do not have friends to support them, or who does not fit into the group, or who does not seem to like the same things or value the same things the way that the perpetrator of violence thinks they should. For women and for presumed women (many transmasculine youth in school context) sexist culture makes them more likely to become victims of sexual harassment and violence by men.

These points were supported by the analysis of the stories told by non-heterosexual and trans youth in the survey. In some of the stories they expressed that the violence they experienced in school was homo- or transphobic, but often it was more complicatedly linked to norms around proper gender expression.

In the 7th grade, two or three 9th grade boys bullied me ruthlessly every day, and that was while I had, and still have, natural curly long hair. The teachers were either blind or somehow did not want to react. I did not dare to seek help outside while I was afraid that it would get worse if I would”rat about it” and”be unmasculine”. (transfeminine young respondent)

In basic education, boys did not tolerate homosexuality and it was experienced as the worst possible thing. The atmosphere was so negative that no-one could be openly gay. “Homo” was the most typical and worst word to be shouted at you. The teachers did not react, even if there was negative discussion on homosexuality in the classroom or if it was used in bullying. In high school, the bullying was not so obvious. There was not so much homo [phobic, homottelu] name-calling, but openly gay people like me were left out of straight men’s friendship circles and contacts with gay people were avoided. Most of my friends were women and other gay men. (non-heterosexual young man)

Homophobic (or transphobic, or heteronormative) name-calling is not directed only towards LGBTI youth but towards anybody or everything (Lehtonen, 2002, 2003, 2010): a broken machine in vocational education could be called “homo”. I have analysed it as a central way to construct proper heteronormative masculinities for boys in school context. In my earlier research, I found that youth reported that “sometimes homophobic name-calling was not targeted towards known gay people while they might get insulted, and it was only used between straight boys” (see Pascoe, 2007; Odenbring, 2019). But of course, especially for LGBTI youth, hearing negative homophobic reactions and name-calling creates an unpleasant atmosphere, even if they are not the direct targets. It might be sometimes difficult to explain using homophobia or transphobia how friendship networks are created in schools, but typically gender and shared values are clearly connected to it. Distancing yourself from openly gays or trans persons can also be a way to secure your own position in the classroom even if you don’t have homophobic or transphobic feelings.

In the stories, it also came out that trans persons had often experienced homophobic reactions and non-heterosexual youth gender-based harassment and bullying in which gendered expressions were used in insulting ways (calling non-heterosexual boys “Miss” or “bitch”).

I have been discriminated against and experienced occasional bullying by boys, while they see me as an aggressive tomboy and think right away that I am a hyper feminist truck driver lesbian, when in reality I would want to be a boy in their group. (transmasculine young respondent)

In the upper secondary education one student went after me. This person spread my photos over the net in a nasty way, commented on my net diary anonymously by referring me as a “fucking lesbian” and always corrected the name I used to my official name, even if s/he [in Finnish gender neutral pronoun hän] knew that I hate it. Even when my name was written on the blackboard, s/he wipe it out and wrote my official name there. The constant bullying and putting down of my identity was too difficult to handle when connected to my fairly difficult depression, and I dropped out of education, even if I would have otherwise enjoyed my training and I would have wanted to finish my studies. (transmasculine young respondent)

Striking elements in the stories of non-heterosexual and trans youth are the fact that violence and exclusion can have so many negative effects on young people’s lives, and that in these stories teachers often did not react actively to prevent the violence faced by LGBT youth.

There are also other intersecting aspects than gender, sexuality and age to be taken into account in analysing violence LGBT youth experience. LGBT youth who are racialised or differently abled are more likely to be victimised by violence. I have not analysed these aspects, but in my research I found out that locality and social class are meaningful aspects (see Lehtonen, 2018). Youth living in rural areas were more likely than those living in cities to both hide their sexuality and gender from other students and their teachers at school, but they also faced negative reactions to their sexuality and gender identity more often than respondents living in cities (see also Odenbring, 2019). Respondents with working-class backgrounds faced violence more often than those with middle-class backgrounds. This was related to the fact that working-class students are more likely to choose to study in highly gender-segregated vocational education compared to the middle-class students, who were more likely to be in general upper secondary education, where there is less bullying in general. (Lehtonen, 2018).

The use of violence in schools is highly gendered, and sometimes sexualised. Men were more often actors in violence in general (controlling boys, girls and others through physical violence and the threat of it), especially in sexual violence towards girls or presumed girls (transmasculine respondents). Homo- and transphobic violence was performed, because gendered and sexual norms were broken by LGBTI youth and others, and this was policed by violence. Respondents also told stories of how they had been controlled and policed based on their gender; this type of gendered violence was probably experienced by LGBTI youth more often than by other youth, as they were more likely to stretch these norms. LGBTI youth might be in a vulnerable position in their schools (feeling and being outside of the groups and their norms, loneliness, mental health issues related to minority stress and body dysphoria and so on); and hence they are easier targets for violence than others. LGBTI youth also face violence based on other reasons (including racism) and can be actors of violence themselves (partially linked to the unjust position they endure). Thus, even if homophobic and transphobic reactions and feelings explain only a minority of the violence experienced by LGBT youth, it is important to analyse the rest of their experiences of violence also from the perspectives of gender, heteronormativity and intersecting differences.

Conclusions and Discussion

Non-heterosexual and trans youth in Finland experience many kinds of violence. Most of the violence they have experienced in their life is neither homophobic nor transphobic, nor based on their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. By focusing only on homo- and transphobic violence, a major part of violence towards LGBT youth is made invisible. This is particularly problematic when thinking about the experiences of violence of non-heterosexual women and transmasculine respondents who often seem to experience heteronormative but not always homo- and transphobic violence, such as the majority of sexual violence.

I discussed the usefulness and problems in using the concepts of homophobia and transphobia in analysing the stories and data on violence against trans and non-heterosexual youth in education and elsewhere. I argue that they leave out the major part of violence, and also some aspects of violence, which are linked to or based on heteronormative practises. Phobia-related concepts can also create a male-centred image of the violence experienced by LGBTI people, while they leave out of focus many parts of heteronormative violence, which is experienced especially often by girls and presumed girls. They are also psychological and medical concepts, which often focus on individual behaviour and emotions. Often, they do not take into account broader societal issues and contexts such as school culture, teachers’ reactions, prevention work, and equality planning.

The focus of interest should be enlarged from homo- and transphobic violence and crimes to all sort of violence towards LGBTI people. This should be done so that the experiences of violence and survival strategies would be analysed from the point of view of heteronormativity. In Finland, as well as elsewhere, better and more efficient methods should be developed to collect data on hate crimes related to sexual orientation and gender identity/expression, and training organised for police, lawyers, and correctional officials. There should be more research done to cover the frequency and types of violence faced by LGBTI people, and the national surveys should include questions on respondents’ sexual orientations and gender identity/expression, as well as questions on LGBTI-specific issues. Intersectional aspects of this type of violence should be acknowledged; it would be vital to keep age, social class, location, cultural, religious and ethnic backgrounds, and other intersecting differences in mind (Boonzaier et al., 2015). More research is also needed on the strategies and actions of LGBTI youth in facing violence or the threat of it, and on the services that should be able to help young people when they encounter violence (schools, police, families, social and health services, non-governmental organisations). It would be important to study how things can be changed for the better, and how it is possible to not only effectively help young LGBTI people in surviving experiences of violence, but also how to prevent heteronormative violence in society.

In educational institutions, starting from early childhood education and primary education through to secondary and tertiary education, safety education and violence prevention should be important aspects in how educational institutions construct their learning environments and teaching. Most educational institutions are already required to plan efforts to promote equality and non-discrimination, and many schools have some kind of violence prevention practices. In the future, educational institutions should focus more on heteronormative violence, and make concrete plans on how to tackle it as part of their equality and non-discrimination planning and violence prevention. Unless heteronormativity, homo- and transphobia, and LGBTI issues and experiences are taken care of, these policies and practices will not fully respond to the need to prevent heteronormative violence. But this is not enough: schools and teachers should also ponder how they, along with their students, could create understanding, teaching contents and practices as well as a student culture that would not re-enforce heteronormativity but question and prevent it. This would demolish the arguments and motivation behind heteronormative violence, including homo- and transphobic violence.

Notes

- 1.

My current research focus is on a diverse group of non-heterosexual and trans youth and their experiences of education and work environments, as well as on texts, such as school books, curricula documents, media, and research reports, and how intersectional differences and normativities are constructed in them, within the project Social and Economic Sustainability of Future Working Life: Policies, Equalities and Intersectionalities in Finland WeAll (2015–2020), which is funded by the Academy of Finland (Strategic Research Funding number 292883). More info: weallfinland.fi. I am thankful for the valuable comments for this chapter to Jon Ingvar Kjaran, Elina Lahelma, Ylva Odenbring and Thomas Johansson.

- 2.

There were more stories by non-heterosexual respondents (N = 335) than trans respondents (N = 167). Fewer non-heterosexual men (N = 116) and transfeminine respondents (N = 18) answered these questions compared to non-heterosexual women (N = 219) and transmasculine respondents (N = 149).

- 3.

Also intersexphobia or interphobia, but in this chapter I focus on LGBT people and not on intersex people. See Lehtonen (2017).

- 4.

In 2017 survey, the question on sexual orientation was directed only at students studying in upper secondary institutions, but students of basic education were also asked their gender identity (grade eight and nine); in the 2019 survey basic education students were also asked their sexual orientation.

- 5.

Non-heterosexual girls’ figures were smaller than those of the boys (17% had experienced threats of physical violence in vocational and 10% in general upper secondary education), but greater than those of heterosexual girls (11% in vocational and 6% in general upper secondary education).

- 6.

In the 2019 survey, non-heterosexual respondents also experienced bullying on a weekly basis more often in basic education (15%, N = 7636) than in vocational (9%, N = 1758) or general (3%, N = 4457) upper secondary education.

- 7.

In the early eighties the first survey was performed to cover LGB people’s experiences and social situation in Finland (Grönfors et al., 1984). It was discovered that every sixth gay or bisexual man had faced violence based on their sexual orientation. Lesbian and bisexual women had faced violence based on sexual orientation clearly less often. In the early 2000s a work environment study was produced (Lehtonen & Mustola, 2004, see also Lehtonen, 2014), in which it was found that 12% of sexual minorities and 8% of trans people had experienced bullying based on their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression at their workplaces. In an earlier interview study, it was discovered that out of the 64 men who were interviewed on issues around safer sex and HIV, 17% had faced violence based on their sexual orientation (Lehtonen, 1999).

References

Adam, B. (1998). Theorizing homophobia? Sexualities, 1(4), 387–404.

Ahmed, S. (2014). Cultural politics of emotions. Edinburgh University Press.

Alanko, K. (2013). Hur mår HBTIQ-unga i Finland? [How well are LGBTQ young people doing in Finland?]. Helsingfors: Ungdomsforskiningsnätverket och Seta.

Blackburn, M. V. (2012). Interrupting hate. Homophobia in schools and what literacy can do about it. Teachers College Press.

Blumenfeld, W. (1992). Homophobia: How we all pay the price. Beacon.

Boonzaier, F., Lehtonen, J., & Pattman, R. (2015). Youth, violence and equality: Perspectives on engaging youth toward social transformation. Editorial for special issue of youth, violence and equality: Local-global perspectives. African Safety Promotion, 13(1), 1–6.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble. Routledge.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810.

Denny, D. (1994). “You’re strange and We’re wonderful”: The gay/lesbian and transgender communities. In J. Sears (Ed.), Bound by diversity (pp. 47–53). Columbia.

DePalma, R., & Atkinson, E. (2009). Interrogating heteronormativity in primary-schools: Project. Trentham Books.

Fagerlund, M., Peltola, M., Kääriäinen, J., Ellonen, N. & Sariola, H. (2014). Lasten ja nuorten väkivaltakokemukset 2013. Lapsiuhritutkimuksen tuloksia. [Violence experiences of children and youth 2013. Results of child victim research] Tampere: Poliisiammattikorkeakoulu.

Fone, B. (2000). Homophobia. A history. Metropolitan Books.

FRA. (2009). Homophobia, transphobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in the EU Member States. Part II: The social situation. Publications Office of the European Union.

FRA. (2014a). EU LGBT survey – European Union lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survey. Main results. Publications Office of the European Union.

FRA. (2014b). Being trans in the European Union. Comparative analysis of EU LGBT survey data. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Publications Office of the European Union.

Grönfors, M., Haavio-Mannila, E., Mustola, K. & Stålström, O. (1984). Esitietoja homo- ja biseksuaalisten ihmisten elämäntavasta ja syrjinnästä [Preliminary information on the life style and discrimination of homo- and bisexual people]. In Sievers, K. & Stålström, O. (Eds.) Rakkauden monet kasvot [Many faces of love]. Espoo: Weilin+Göös, 132–160.

Hearn, J. (1998). The violences of men: How men talk about and how agencies respond to men’s violence to women. Sage Publications.

Herek, G. (1990). The context of anti-gay violence: Notes on cultural and psychological heterosexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 5(3), 316–333.

Herek, G. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NRCS, 1(2), 6–24.

Hiitola, J., Jyränki, J., Karma, H., & Sorainen, A. (2005). Mitä ei voi ajatella?: puhetta seksuaaliseen väkivaltaan liittyvistä hiljaisuuksista [What you cannot think?: Talk on silences around sexual violence]. The Finnish Journal of Gender Studies, 18(4), 61–66.

Humppi, S-M. (2008). Poliisin tietoon tullut lapsiin ja nuoriin kohdistuva väkivalta [Reported violence against children and youth to police]. Tampere: Poliisiammattikorkeakoulu.

Huotari, K., Törmä, S. & Tuokkola, K. (2011). Syrjintä koulutuksessa ja vapaa-ajalla: Erityistarkastelussa seksuaali- ja sukupuolivähemmistöihin kuuluvien nuorten syrjintäkokemukset toisen asteen oppilaitoksissa [Discrimination in education and leisure time: With special focus on discrimination experienced by young people belonging to sexual and gender minorities who study at the upper secondary education]. Helsinki: Ministry of Interior Affairs.

Hutchins, L., & Kaahumanu, L. (Eds.). (1991). Bi any other name. Alyson.

Ikonen, R. (2019). Lasten ja nuorten kokema väkivalta: tuloksia Kouluterveyskyselystä ja Lasten terveys, hyvinvointi ja palvelut –tutkimuksesta. In U. Korpilahti, H. Kettunen, E. Nuotio, S. Jokela, V. Nummi, & P. Lillsunde (Eds.), Väkivallaton lapsuus – toimenpidesuunnitelma lapsiin kohdistuvan väkivallan ehkäisystä 2020–2025 [Non-violent childhoods – Action plan for the prevention of violence against children 2020–2025] (pp. 73–78). Helsinki:THL.

Jungar, K., & Peltonen, S. (2016). Acts of homonationalism: Mapping Africa in the Swedish media. Sexualities, 20(5–6), 715–737.

Kankkunen, P., Harinen, P., Nivala, E. & Tapio, M. (2011). Kuka ei kuulu joukkoon? Lasten ja nuorten kokema syrjintä Suomessa [Who does not belong to the group? Discrimination experienced by children and youth in Finland]. Helsinki: Ministry of Interior Affairs.

Kjaran, J., & Lehtonen, J. (2017). Windows of opportunities: Nordic perspectives on sexual diversity in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(10), 1035–1047.

Kulick, D. (2009). Can there be an anthropology of homophobia? In D. Murray (Ed.), Homophobias. Lust and loathing across time and space (pp. 19–33). Duke University Press.

Lehtonen, J. (1999). Homot väkivallan kohteina [Violence against gays]. In Lehtonen, J. (Ed.) Homo Fennicus - miesten homo- ja biseksuaalisuus muutoksessa [Homo Fennicus – homo- and bisexuality of men in change]. Helsinki: Tasa-arvoasiain neuvottelukunta, STM, 93–108.

Lehtonen, J. (2002). Heteronormativity and name-calling – Constructing boundaries for students’ genders and sexualities. In V. Sunnari, J. Kangasvuo, & M. Heikkinen (Eds.), Gendered and sexualised violence in educational environments (pp. 201–215). Oulu University Press.

Lehtonen, J. (2003). Seksuaalisuus ja sukupuoli koulussa [Sexuality and gender at school]. Helsinki: Yliopistopaino.

Lehtonen, J. (2007a). Seksuaalisen suuntautumisen ja sukupuolen moninaisuuteen liittyvä syrjintä [Discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender diversity]. In O. Lepola & S. Villa S (Eds.), Syrjintä Suomessa 2006 [Discrimination in Finland 2006] (pp. 18–65). Helsinki: Ihmisoikeusliitto.

Lehtonen, J. (2007b). Seksuaali- ja sukupuolivähemmistöt, väkivalta ja poliisin toimet [Sexual and gender minorities, violence and police activities]. Helsinki: Tasa-arvotiedonkeskus.

Lehtonen, J. (2010). Gendered post-compulsory educational choices of non-heterosexual youth. European Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 177–191.

Lehtonen, J. (2014). Sukupuolittuneita valintoja? Ei-heteroseksuaaliset ja transnuoret koulutuksessa [Gendered choices? Non-heterosexual and trans youth in education]. The Finnish Journal of Gender Studies, 27(4), 67–71.

Lehtonen, J. (2017). Hankala kysymys. Intersukupuolisuus suomalaisissa koulu- ja työelämätutkimuksissa [Complex question. Intersex in the Finnish school and work environment research]. Sukupuolentutkimus, 30(1), 71–75.

Lehtonen, J. (2018). Ei-heteroseksuaalisten poikien ja transnuorten kokemukset ja valinnat koulutuksessa [Experiences and choices of non-heterosexual boys and trans youth in education]. In Kivijärvi, A., Huuki, T. & Lunabba, H. (Eds.) Poikatutkimus [Boy studies]. Tampere: Vastapaino, 121–145.

Lehtonen, J., & Mustola, K. (Eds.). (2004). “Straight people Don’t tell, do they?” negotiating the boundaries of sexuality and gender at work. Helsinki: Ministry of Labour.

Lehtonen, J., Palmu, T., & Lahelma, E. (2014). Negotiating sexualities, constructing possibilities: Teachers and diversity. In M.-P. Moreau (Ed.), Inequalities in the teaching profession. A global perspective (pp. 118–135). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lloyd, M. (2013). Heteronormativity and/as violence: The ‘Sexing’ of Gwen Araujo. Hypatia, 28(4), 818–834.

Luopa, P., Kanste, O. & Klemetti, R. (2017). Toisella asteella opiskelevien sateenkaarinuorten hyvinvointi 2017. Kouluterveyskyselyn tuloksia [Well-being of rainbow youth studying in the upper secondary education 2017. Results of the School Health Survey]. Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos.

Manalansan, M. (2009). Homophobia at New York Central. In D. Murray (Ed.), Homophobias. Lust and loathing across time and space (pp. 34–47). Duke University Press.

Martinsson, L. & Reimers, E. (Eds.) (2008). Skola i normer [School in norms]. Malmö: Gleerups.

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30(3), 1771–1800.

Murray, D. (Ed.). (2009). Homophobias. Lust and loathing across time and space. Duke University Press.

Näsi, M. (2016). Nuorten rikoskäyttäytyminen ja uhrikokemukset 2016 [Youth criminal behaviour and victim experiences 2016]. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto.

O’Brien, J. (2008). Afterword: Complicating homophobia. Sexualities, 11(4), 496–512.

Odenbring, Y. (2019). Standing alone: Sexual minority status and victimisation in a rural lower secondary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1698064

Pascoe, C. J. (2007). Dude you’re a fag. Masculinity and sexuality in high school. University of California Press.

Patai, D. (1998). Heterophobia. Sexual harassment and the future of feminism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Peura, J., Pelkonen, P. & Kirves, L. (2009). Raportti nuorten kiusaamiskyselystä. Miksi kertoa kun se ei auta? (Report on youth bullying survey. Why tell when it does not help?]. Helsinki: Mannerheimin Lastensuojeluliitto.

Rossi, L.-M. (2006). Heteronormatiivisuus. Käsitteen elämää ja kummastelua. [Heteronormativity: Queering the concept and its brief history]. Kulttuurintutkimus, 23(3), 19–28.

Ruuska, T. (2019). Lukiossa opiskelevien transnuorten kouluhyvinvointi [School Well-being of trans youth in general upper secondary education]. Pro gradu-tutkielma, Helsingin yliopisto.

Sears, J. (1997). Thinking critically/intervening effectively about heterosexism and homophobia: A twenty-five-year research retrospective. In J. Sears & W. Williams (Eds.), Overcoming heterosexism and homophobia (pp. 13–48). Columbia University Press.

Sedgwick, E. (1990). Epistemology of the closet. University of California Press.

Smith, I., Oades, L., & McCarthy, G. (2012). Homophobia to heterosexism: Constructs in need of re-visitation. Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review, 8(1), 34–44.

Taavetti, R. (2015). “Olis siistiä, jos ei tarttis määritellä…” Kuriton ja tavallinen sateenkaarinuoruus [“It would be cool not to have to define yourself”. Undisciplined and ordinary rainbow youth]. Helsinki: Nuorisotutkimusseura ja Seta ry.

Telakivi, L., Moring, A. & Huuska, M. (2019). Sukupuoli- ja seksuaalivähemmistöihin kuuluvat lapset ja nuoret [Children and youth belonging to gender and sexual minorities]. In U. Korpilahti, H. Kettunen, E. Nuotio, S. Jokela, V. Nummi, P. Lillsunde (eds.) Väkivallaton lapsuus – toimenpidesuunnitelma lapsiin kohdistuvan väkivallan ehkäisystä 2020–2025 [Non-Violent Childhoods – Action Plan for the Prevention of Violence against Children 2020–2025]. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 449–457.

Tiby, E. (1999). Hatbrott? Homosexualla kvinnors och mäns berättelser om utsatthet för brott [Hate crime? Stories of lesbians and gay men on being victims of crimes]. Stockholm: University of Stockholm.

Weinberg, G. (1972). Society and the healthy homosexual. St. Martin’s.

Wickberg, D. (2000). Homophobia: On the cultural history of an idea. Critical Inquiry, 27, 42–57.

Willoughby, B., Hill, D., Gonzalez, C., Lacorazza, A., Macapagal, R., Barton, M., & Doty, N. (2011). Who hates gender outlaw? A multisite and multinational evaluation of the genderism and transphobia scale. International Journal of Transgenderism, 12(4), 254–271.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lehtonen, J. (2021). Heteronormative Violence in Schools: Focus on Homophobia, Transphobia and the Experiences of Trans and Non-heterosexual Youth in Finland. In: Odenbring, Y., Johansson, T. (eds) Violence, Victimisation and Young People. Young People and Learning Processes in School and Everyday Life, vol 4. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75319-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75319-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-75318-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-75319-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)