Abstract

High prevalence of intimate partner violence against women and high levels of gender equality in Finland yield to what has been called the “Nordic paradox.” It has been argued that the high level of gender equality has caused the need for IPV interventions and especially the gendered perspective to be overlooked. However, there has been recent and ongoing development in IPV intervention and prevention in regard to perpetrator programs, couple therapy, and programs to address post-separation stalking. Training programs for social and healthcare professionals and the police have been developed, as well as for teachers and other professionals at school. We hope the current government’s new action plan for combating violence against women will contribute to the development of efficient interventions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

8.1 Introducing Ourselves to You

I, Juha, am a clinical psychologist, family psychotherapist, trainer, and supervisor. When working as doctoral student, the local crisis center, Mobile, developed an initiative, forming a group for perpetrators at the new founded Psychotherapy Training and Research Centre at the University of Jyväskylä. My colleague, Aarno Laitila, and I were interested on this initiative. This was a start of the development of a multi-professional network against violence against women and research projects concerning IPV described later in this chapter. Since then, many students and researchers have participated in these projects, and interdisciplinary cooperation at the University of Jyväskylä has developed, including international conferences and the Violence Studies program. We, Helena, Heli, and Salla, started our research careers in the IPV research projects at the University of Jyväskylä. I, Helena, started work in the IPV projects in 2008, first by doing my master’s thesis on the data, and later, after few years of working as a clinical psychologist in the prison and in mental healthcare, I began my PhD program. My research interest from the start has been in gendered identity work, which, in the context of IPV treatment, offers an important perspective to change processes. During my doctoral studies, I also worked as a facilitator in the group for perpetrators and started training to become an integrative psychotherapist. Currently, besides doing clinical work, I work as a post-doctoral research fellow in an EU-funded research project at the University of Tampere in which training for school professionals on GBV is developed. My (Heli) first touch with domestic violence as a research topic was when I was planning a topic for my bachelor thesis as a second-year psychology student around 2012. I was interested in feminism and other socio-political issues and felt that domestic violence research offered the best way to include these interests in my psychology studies. I have been on that path ever since, writing my bachelor and master theses on the subject and then continuing to work on my dissertation which deals with prevalence and effects of domestic violence within healthcare settings. Since 2016, I have also worked as a facilitator in the group intervention for perpetrators of domestic violence, which I have found to be a crucial and very rewarding addition to my research work. I, Salla, too became interested in violent behavior and especially domestic violence during my psychology bachelor and master studies in the University of Jyväskylä. During my studies, I was focused on forensic psychology and have had courses in Canada and the Czech Republic as well as in Finland. My bachelor and master theses were focused on post-separation stalking and professionals’ attitudes toward stalking. Since graduating as a clinical psychologist, I have been working in organizations offering help and guidance to people whose lives are affected by domestic violence. Currently, in 2020, I work in Tukikeskus Varjo, a national support center for post-separation stalking, and pursue doctoral studies on post-separation stalking, focused on the perpetrators. I also work as a facilitator in University of Jyväskylä’s group intervention for perpetrators.

8.2 Country Overview

Finland is a relatively small country population with only 5.5 million inhabitants. However, Finland is the fifth-largest country in Western Europe (338,440 km2), and the population is mostly living in cities of southern Finland, making many parts of the country very thinly inhabited. According to Statistics Finland (2019), 7.3% of the entire population has foreign backgrounds. Most of them were first-generation immigrants. The largest group of persons with foreign backgrounds were from Russia or the former Soviet Union and Estonia.

Finland’s GDP grew by 1.7% in 2018 and amounted to EUR 232 billion. GDP per capita was 40,612 euros in 2017. Most Finns are Christians. The largest religious community in Finland is the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland to which about 70% of the population belongs.

A high standard of education, social security, and healthcare exists in Finland, all financed by the state. By the end of 2017, 72% of the population aged 15 or over had completed a post-comprehensive level qualification (i.e., high school or vocational education; Statistics Finland, 2019). Thirty-one percent of the population had completed a tertiary level qualification (i.e., bachelor, master’s, or doctoral education). The educational level of the population has risen in the past few decades mainly as a result of women seeking higher educations. Today, there are slightly more women with tertiary level education than men. Despite the rise in the education level of women, the focus of education and career paths has remained strongly segregated by gender.

Finland was the first country in the world to have universal and equal voting rights for men and women in the parliamentary elections in 1907. Women’s representation in Parliament has increased over the decades but has not thus far exceeded 50%. Finland had the fourth highest gender equality index in EU 2017 after Sweden, Denmark, and France (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2019). This has led to the development of a strong notion of Finnish gender neutrality and the more recent notion of gender equality in extra-parliamentary politics in the 1970s and in law in the 1980s (Hearn & McKie, 2010). The Strategic Program of Government in 2015 reflects the main discourse that “Finland is also a land of gender equality” (Program of Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s Government, 2015).

8.3 Intimate Partner Violence in Finland

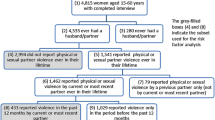

Violence experienced by Finnish women has been assessed in two interview surveys conducted in 1998 and 2006. According to the latest survey (Piispa et al., 2006), 43.5% of women had experienced physical or sexual violence or threat of it by a man at least once after turning 15. Around one in five women had experienced violence or threats of violence by their current partner. Men’s experiences of victimhood were analyzed in a questionnaire survey in 2010 (Heiskanen & Ruuskanen, 2010). Men were most often victims of violence committed by strangers (42%) or acquaintances (24%) since the age of 15. In both violence groups, the perpetrators were most often men. Regarding violence committed by partners, 16% of men living in a relationship had experienced violence or threats committed by their partner at least once. A 2014 survey conducted by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights among the 28 EU Member States showed that the lifetime prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence against women by intimate partners was 30% in Finland, being clearly above average in the EU (FRA, 2014). Intimate partner violence (IPV) among LBGTQ partners has not been currently addressed or studied in Finland.

The homicide rate is higher than that of other Nordic countries, which is mainly due to alcohol-related offences committed by socially excluded, male alcoholics (Lehti & Suonpää, 2020). Twenty percent of all homicides in Finland are attributed to a woman’s death at the hands of a current or former partner, according to the National Research Institute of Legal Policy (Kivivuori & Lehti 2006; Lehti, 2016). Female intimate partner homicides (IPHs) constitute approximately 60% of all female homicides, but male IPHs make up only approximately 5% of all male homicides. The overall homicide rate has been in decline during the past 20 years, but there is no decreasing tendency in intimate partner femicides.

High prevalence of IPV against women and high levels of gender equality appear to exist together in Finland as well as in other Nordic countries, producing what has been called the “Nordic paradox” by Gracia and Merlo (2016). One theory the authors suggest was that Nordic countries may be suffering from a backlash effect as traditional definitions of both manhood and womanhood begin to be challenged in a meaningful way. Another possible explanation is information bias, i.e., women in Nordic countries may feel freer to talk about IPV because of their equal status. However, the survey of European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, 2014) showed lower levels of disclosure of IPV to the police in Nordic countries as compared to other EU countries. Country level of gender equality did not have an effect on the individual victim-blaming attitudes (Ivert et al., 2018). Violence against women by non-partners and levels of acceptability and victim-blaming attitudes in cases of violence against women also support the high prevalence of IPV against women in Nordic countries (Gracia & Lila, 2015; Gracia & Merlo, 2016).

Due to the widely accepted notion of Finland as a gender equal (or neutral) country, a gender perspective is often presented as self-evident. However, it tends to disappear in concrete practice, where dimensions of gender and power are not addressed sufficiently (Wemrell et al., 2019). The relative absence of a gender perspective, related to an associated assumption of gender equality, has been found to have potentially problematic consequences. For example, substantial responsibility for violence is often placed on female victims. Within healthcare, professionals have been observed to adopt such understandings of IPV that enable them to focus on fixing the injuries caused by IPV without intervening with the violence itself (Husso et al., 2012). This happens despite (or because) violent experiences are common among healthcare professionals themselves (Siltala et al., 2019).

8.4 Challenges and Issues in IPV Services in Finland

It can be argued that the main problem in Finland is the lack of intervention, which allows violence to continue (Husso et al., 2012; Niemi-Kiesiläinen, 2004). Finland criminalized rape in marriage in 1994, being one of the last European countries to do so. The legislation has been modernized over the years in order to improve the position of victims of intimate partner violence and sexual violence, in particular. For instance, even petty assaults occurring in an intimate relationship were made subject to official prosecution in 2011; sexual intercourse with a defenseless party was specified as rape in 2011, and stalking was criminalized in 2014.

The Finnish government published its first Program for the Prevention of Prostitution and Violence against Women in 1997 (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 1997), and enhanced it in 2002, to raise awareness of violence and its impact on individuals. In 2008, the UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) criticized Finland for its lack of effective policy development on IPV (Hearn & McKie, 2010). In 2014, CEDAW recognized the National Action Plan to Reduce Violence against Women 2010–2015, but was critical that insufficient resources have been allocated to the implementation of the plan and that the incidence of violence against women remains high (CEDAW, 2014). The lack in services for victims of gender-based violence (GBV), which was also criticized in the CEDAW report, has lately been improved. Women’s shelters, which were formerly operating on the initiative of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), are now funded and organized by the state. A 24-h free helpline service called Nollalinja has also been established for victims. However, there is still an absence of an effective institutional mechanism to coordinate, monitor, and assess measures at the governmental level to prevent and address violence against women. Municipalities are legally responsible for securing adequate services for victims, but many do not allocate enough resources for these services. Also, work with perpetrators of IPV to end violence is not coordinated or funded nationally , and the programs vary in their approaches (Holma & Nyqvist, 2017). These programs are carried out mostly by NGOs and are based on voluntary participation.

8.5 Recent Developments and Projects

A few research and development projects concerning couple therapy in cases of IPV have been carried out by the Psychotherapy Training and Research Centre at the University of Jyväskylä in cooperation with several social and healthcare service. There is considerable controversy in the field over the indications for couple therapy in cases of IPV. However, a growing body of research has emphasized its benefits. The Jyväskylä research project on couple therapy for IPV was conducted within a cooperative multicenter research network (Vall et al., 2018). The project data were gathered between 2009 and 2013. Findings show how important it is that therapists are aware that male perpetrators exert pressure to justify their behavior and that female clients try to change the topic from the male partner’s justification to address what has actually happened, which has been the act of violence. Therapists have to try to give power to the marginalized voices and give voice to the female client while acknowledging the male client at the same time. Detecting abuse of power and dominance seems to be crucial for the therapeutic outcome. When abuse of power is addressed, it should also be accompanied by strategies to increase the therapeutic alliance. Moreover, violent behavior, responsibility, parenthood, and client satisfaction emerged as crucial topics. It is important that the presence and forms of violent behavior are assessed throughout the therapy process and addressed continually to detect possible changes. It was found that in cases of psychological abuse, clients may have more difficulty positioning themselves as responsible for the violence and might ask their partner to be held responsible for it as well. Therefore, accepting responsibility would seem to be especially crucial when starting couple therapy for psychological IPV. The findings also highlight parenthood as an important theme in IPV couple therapy conversations. It is essential that therapists take into account the views of children affected by the violence between their parents. Parenthood may strongly motivate IPV perpetrators to take responsibility and work to change their behavior. It seems important that therapists are active in their approach, try to make everyone feel heard, and are able to focus on the abusive behavior. Focusing on the abuse should be done by pointing out the harmful way of behaving, not blaming the person’s identity by, for example, naming them as the perpetrator. Identity blaming has been noticed to be very affect provoking (Päivinen et al., 2016a, b).

A more recent and ongoing project is multi-couple treatment in cases of IPV. The Safe Family project is targeted at families and couples who have experienced domestic violence but now want to stop the use of violence in their relationship and prevent the models of violent behavior passing to the next generation. After the assessment period, it is possible for the couples to take part in multi-couple group sessions. This possibility applies to couples that have shown motivation and commitment toward non-violent behavior, and it is considered safe enough to continue in the program. The aim of the multi-couple group is to further support the non-violent behavior, strengthen the abilities for interaction, and build up the capacity to calm down. The model originates from the model by Sandra Stith et al. (2011). The adapted model is a 12-session program with different themes and the use of the group as a reflective team. The Safe Family project takes place in the North Savo region of Finland and is managed by the Kuopio mental health association. The project works in close cooperation with the public sector and other associations (NGOs) that work in the field of domestic violence in the region. The project also cooperates with a few international experts on violence and collaborates with the Department of Psychology at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

Post-separation stalking and intimate partner stalking are defined as a form of IPV. Post-separation stalking is defined here as repeated unwanted acts toward a former intimate partner, in order that the acts cause fear and anxiety to a reasonable person. Knowledge and training for authorities on stalking has been very rare, if any, in Finland. The aims of a Finnish VARJO project, carried out during 2012–2017, were to strengthen the safety of families suffering from violent post-separation partner stalking, improve precautionary work, and create possibilities for supporting victims’ functioning through peer support and help in their recovery from the stalking experience. The project’s target group included the immediate victims of stalking, children of the families, other family members affected by stalking, and stalkers. The project arranged several seminars for authorities, developed services for victims of stalking and other family members, and published guidebooks on intimate partner stalking and digital stalking. Throughout the years, experts by experience have had a great role in the work of the project, in example giving their expertise and views of how they have been acknowledged in various institutions and services of the Finnish society, and contributing to the educational material produced on post-separation stalking. After 2017, VARJO project has continued as a VARJO National Support Centre for post-separation violent stalking, funded by the Funding Centre for Social Welfare and Health Organizations (STEA), and continues to help families encountering post-separation stalking as well as aims to develop services and increase knowledge about the stalking phenomenon.

The programs for perpetrators of IPV started in the 1990s and are carried out by NGOs. The Jyvaskyla model of working with IPV started 20 years ago as a multi-professional collaborative project in Jyvaskyla, Finland, by two main collaborating agencies, the local Crisis Center Mobile and Jyvaskyla University Psychotherapy Training and Research Centre. The Jyvaskyla program for perpetrators is part of multi-agency networking of public social and health services as well as police. The aim of the network is to raise awareness on IPV among professional and develop services for victims, eyewitnesses, and perpetrators. The program itself is voluntary based and non-manualized. The partners are met regularly, and cooperation with victim services is constant. The main principles of the group treatment include a focus on security, violence, choices, feelings of guilt, and masculine identity (Holma et al., 2006; Päivinen et al., 2016b). When attending the group treatment, a perpetrator commits for at least 15 sessions. There is no limit to the number of sessions, but the average length is about 30 sessions, which is 1 year. The program is voluntary, and most of the participants are referred by the social and health agencies. The group treatment is possible only after individual sessions at the Crises Centre Mobile. The groups are semi-open, meaning that each group consists of people in different phases of their treatment. New participants are taken in a couple of times a year, and the new participants agree to minimum of 15 sessions. However, the perpetrators are free to stay longer if they wish.

During the two decades the program has been in existence, the process and utility of group treatment have been studied by applying discursive and narrative approaches (Päivinen et al. 2016b). These research topics can be grouped under two headings: gendered perspective and strategies of therapists. Gendered perspective entails analysis of gendered views of violence and the couple relationship and masculine identity in relation to violence (fatherhood, sexuality). One aspect of masculine identity that is often raised is fatherhood, since most of the participants have children, and the therapists therefore repeatedly refer to the viewpoint of women and children in the group conversations. Combining fatherhood and violent behavior in one’s identity produces a serious contradiction, and the therapists actively addressed this issue to promote the motivation to change. Trauma history of the participants needs to be faced in group treatment, as over half of the men in the group therapy had experienced violence in their childhood and youth. Group members were able to position themselves in the place of the victim of their own violence through their own traumatic childhood experiences. This enabled them to take up the position of a responsible father, which further motivated the cessation of violence.

Several studies on the group program have compared men with good and poor outcomes. The good outcome clients were characterized by better ability to describe their thoughts, feelings, and interpretations. As opposed to the good outcome clients, the poor outcome clients were characterized by greater use of concrete and indicative language in a monological mode, that is, not allowing alternative viewpoints to be discussed and formulating closed utterances (Räsänen et al., 2012a). The men varied in their degree of motivation to participate in the group and in their stage of change, which presents the therapists with the challenge of flexibly adapting their interventions (Räsänen et al., 2014). The therapists used more indicative language, i.e., asking questions that did not need any elaboration such as “Who called the police?” and “Were the children at home when this happened?” at the beginning of the group treatment. It was possible to answer these questions with one or two words referring to concrete things or people, and therefore, engagement in further discussion or more complicated meaning-making becomes unnecessary. The therapists used more conversational dominance and a more structured approach when focusing on the consequences of violence and the clients’ responsibility. Later, the therapists took a more non-dominant position and made greater use of dialogical responses and on the symbolic level (Räsänen et al., 2012b). In the symbolic level of expression, there are more varying meanings for the concepts used, and thus, more effort is required for understanding. For example, by answering “I don’t know the answer to your question but what I wonder is what it would mean to you if it was inherited or what if it wasn’t,” the facilitators used an open, reflective style of responding, inviting clients to engage in more profound consideration of their feelings and thoughts.

A study showed that those men lacking mentalizing speech, i.e., they were unable to recognize and verbalize their emotions at the beginning of the group treatment, did not recognize the effects on their victims of their psychological and emotional violence and had problems in recognizing their spouses’ mental states (Kuurtokoski, 2009). The problems of mentalizing were associated with continuing psychological IPV. Thus, it seems that, for perpetrators, improved recognition of their spouse’s mental states is essential in reducing psychological violence.

The therapist has to be able to adapt their intervention approach to suit the needs of different men at different stages of change, reflexivity, and motivation. The main aim of the perpetrator program is to construct a new identity with a new understanding of parenthood and a more flexible attitude to masculinity (Päivinen & Holma, 2017).

Efforts in tackling IPV and GBV also include training professionals in identifying and intervening with the problem. However, this knowledge and skills training has not generally been part of basic education of the social, health, and educational professionals. Also, lack of coordination of such training has existed. In the past few years, there have been several development projects in Finland, co-funded by the European Commission, in which such training has been developed. The project, Enhancing Professional Skills and Raising Awareness on Domestic Violence, Violence against Women and Shelter Services (EPRAS), focused on the needs of social and healthcare professionals as well as the police in addressing IPV (Nikander et al., 2019). The project analyzed the training needs of these professionals and developed an online training program for multi-sectorial use.

Another project has followed, in which a training program for teachers and other professionals at school is being developed (see https://projects.tuni.fi/erasegbv/). This project, Education and Raising Awareness in Schools to Prevent and Encounter Gender-Based Violence (ERASE GBV), answers the urgent need of preventing and intervening GBV in the school context, among children and youth. The project also gathers information on the experience, knowledge, and skills of the professionals, and the developed online training will be based on this information.

The online format of these training programs makes them easy to access. However, for a more effective knowledge building and skills training, training among peer groups or work communities would be more likely to foster shared understanding of the problem and unified procedures of intervention. The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare has taken up coordination of the different online trainings for social and healthcare professionals including trainings on intervening IPV and GBV in Finland.

8.6 Conclusion

Finland is a country with paradoxical amounts of IPV in the context of high gender equality. Victim-blaming attitudes appear to be quite resistant to change over the years, and the constant disappearance of the structural gender perspective in the discussions of violence supports this resistance. The work with both victims and perpetrators of violence lacks coordination, and more intervention programs are needed. More adequate training and intervention procedures should be provided for professionals working in social and healthcare services in order to increase the identification of IPV. The number of migrants is increasing, and special services are needed as well as efforts to eliminate issues, such as genital female genital mutilation and so-called honor killings. Furthermore, next steps in preventing gender-based violence in Finland need to include early preventative, educational programs that reach the general population and children in particular. Educating the educators of schoolchildren is a promising action in increasing early detection, support, and guidance to services for the most vulnerable group that are affected by violence, the children.

The current government has drawn up an action plan for combating violence against women on 2020 (Ministry of Justice, 2020). The cross-cutting theme of the action plan is the prevention of violence. Of specific forms of violence, the action plan covers honor-related violence and digital violence. In addition, emphasis is placed on the work to be carried out with perpetrators of violence and on the competence development of authorities responsible for criminal investigation, criminal procedure, and criminal sanctions.

References

CEDAW. (2014). Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of Finland. Retrieved from: file://fileservices.ad.jyu.fi/homes/jholma/Downloads/Komitean%20loppup%C3%A4%C3%A4telm%C3%A4t.pdf

European Institute for Gender Equality (2019) Gender Equality Index. Retrieved from: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2019

FRA. (2014). Violence against women: An EU-wide survey. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights.

Gracia, E., & Lila, M. (2015). Attitudes towards violence against women in the EU. Publications Office of the European Union.

Gracia, E., & Merlo, J. (2016). Intimate partner violence against women and the Nordic paradox. Social Science & Medicine, 157, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.040

Hearn, J., & McKie, L. (2010). Gendered and social hierarchies in problem representation and policy processes: ‘Domestic violence’ in Finland and Scotland. Violence Against Women, 16, 136–158.

Heiskanen, M., & Ruuskanen, E. (2010). Tuhansien iskujen maa - Miesten kokema väkivalta Suomessa. The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI). Retrieved from: https://www.heuni.fi/en/index/publications/heunireports/reportseries66.tuhansieniskujenmaa-miestenkokemavakivaltasuomessa.html

Holma, J., & Nyqvist, L. (2017). Väkivaltatyö miesten kanssa. In J. Niemi, H. Kainulainen, & P. Honkatukia (Eds.), Sukupuolistunut väkivalta: oikeudellinen ja sosiaalinen ongelma (pp. 104–120).

Holma, J., Partanen, T., Wahlström, J., Laitila, A., & Seikkula, J. (2006). Narratives and discourses in groups for male batterers. In M. Lipshitz (Ed.), Domestic violence and its reverberations (pp. 59–83). Nova Science Publisher.

Husso, M., Virkki, T., Notko, M., Holma, J., Laitila, A., & Mäntysaari, M. (2012). Making sense of domestic violence intervention in professional health care. Health and Social Care in the Community, 20, 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01034

Ivert, A. K., Merlo, J., & Gracia, E. (2018). Country of residence, gender equality and victim blaming attitudes about partner violence: A multilevel analysis in EU. European Journal of Public Health, 28(3), 559–564. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx138

Kivivuori, J., & Lehti, M. (2006). The social composition of homicide in Finland, 1960–2000. Acta Sociologica, 49(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699306061900

Kuurtokoski, O. (2009). Parisuhdeväkivalta mentalisaation näkökulmasta. Master’s thesis. Department of Psychology, University of Jyväskylä.

Lehti, M. (2016). Henkirikoskatsaus. Kriminologian ja oikeuspolitiikan instituutti. Katsauksia 10/ 2016.

Lehti, M., & Suonpää, K. (2020). Henkirikokset. In P. Danielsson (Ed.), Rikollisuustilanne 2019: Rikollisuuskehitys tilastojen ja tutkimusten valossa (pp. 9–36). (Katsauksia; 2020, Nro 42). Helsingin yliopisto, kriminologian ja oikeuspolitiikan instituutti. Retrieved from: https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/320755/Katsauksia_42_Rikollisuustilanne_2019_2020.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Ministry of Justice. (2020). Action plan for combating violence against women for 2020–2023. Publications of the Ministry of Justice. Memorandums and statements. Retrieved from: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-259-835-6

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. (1997). Pekingistä Suomeen. Suomen hallituksen tasa-arvo-ohjelma. Publications of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

Niemi-Kiesiläinen, J. (2004). Rikosprosessi ja parisuhdeväkivalta. WSOY.

Niklander, E., Notko, M., & Husso, M. (2019). Intervening in domestic violence and training of professionals in social services and health care and the police: Evaluation of the EPRAS project.

Nollalinja. https://www.nollalinja.fi/in-english/

Päivinen, H., Holma, J., Karvonen, A., Kykyri, V.-L., Tsatsishvili, V., Kaartinen, J., et al. (2016a). Affective arousal during blaming in couple therapy: Combining analyses of verbal discourse and physiological responses in two case studies. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38(4), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-016-9393-7

Päivinen, H., Vall, B., & Holma, J. (2016b). Research on facilitating successful treatment processes in perpetrator programs. In M. Ortiz (Ed.), Domestic violence: Prevalence, risk factors and perspectives, family issues in the 21st century (pp. 163–187). Nova Science Publishers.

Päivinen, H., & Holma, J. (2017). Towards gender awareness in couple therapy and in treatment of intimate partner violence. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 1(2), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868017X15090095287019

Piispa, M., Heiskanen, M., Kääriäinen, J., & Sirén, R. (2006). Violence against women in Finland. (English summary). National Research Institute of Legal Policy. Publication No. 225. The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI). Publication Series No. 51. Helsinki.

Programme of Prime Minister Sipilä’s Government. (2015). https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/sipila/government-programme

Räsänen, E., Holma, J., & Seikkula, J. (2012a). Constructing healing dialogues in group treatment for men who have used violence against their intimate partners. Social Work in Mental Health, 10(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2011.607377

Räsänen, E., Holma, J., & Seikkula, J. (2012b). Dialogical views on partner abuser treatment: Balancing confrontation and support. Journal of Family Violence, 27(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-012-9427-3

Räsänen, E., Holma, J. & Seikkula, J.(2014) Dialogues in partner abusive clients’ group treatment: Conversational tools used by counselors with differently motivated clients. Violence and Victims, 29 (2), 195-216. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00064R1

Siltala, H. P., Holma, J. M., & Hallman, M. (2019). Family violence and mental health in a sample of Finnish health care professionals: The mediating role of perceived sleep quality. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 231–243.

Statistics in Finland. (2019). Population. Retrieved from: https://www.stat.fi/til/vrm_en.html

Stith, S. M., McCollum, E. E., & Rosen, K. H. (2011). Couples therapy for domestic violence: Finding safe solutions. American Psychological Association.

Vall, B., Päivinen, H., & Holma, J. (2018). Results of the Jyväskylä research project on couple therapy for intimate partner violence: Topics and strategies in successful therapy processes. Journal of Family Therapy, 40(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12170

Wemrell, M., Stjernlö, S., Aenishäslin, J., Lila, M., Hracia, M., & Ivert, A-K (2019). Towards understanding the Nordic paradox: A review of qualitative interview studies on intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) in Sweden. Sociology Compass. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12699

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 American Family Therapy Academy (AFTA)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Holma, J., Päivinen, H., Siltala, H., Kaikkonen, S. (2021). Intimate Partner Violence in Finland. In: Stith, S.M., Spencer, C.M. (eds) International Perspectives on Intimate Partner Violence. AFTA SpringerBriefs in Family Therapy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74808-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74808-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-74807-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-74808-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)