Abstract

Evidence-based research have confirmed that various models of psychotherapy produce very positive results, but no particular psychotherapeutic technique has shown a significant superiority compared to the others. A factor significantly related to patient or family satisfaction and to the final result of psychotherapy seems to be the quality of the therapeutic alliance or working alliance (WA), and the attachment paradigm has been used as a key for interpretation and assessment of this dimension. Another relational factor that seems to be a common goal for most therapies is to increase mentalization of patients and their families, but how can this factor be measured within therapeutic relationships? Following a systemic perspective that takes this evidence into account and pursues a biopsychosocial vision, in the manualization of a psychotherapeutic protocol, relational indexes as working alliance, attachment, and mentalization can be considered. Different models of assessment of WA, attachment, and mentalization in psychotherapy will be described. Unfortunately, most of them assess these dimensions as individual characteristics. Reflective function in the family (RFF) will be described, one of the few tools to evaluate mentalization in family therapy following a systemic perspective. Its integration in the manualization of a therapeutic protocol is suggested.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Effectiveness and Manualization of Psychotherapies

Are psychotherapies really effective? Are there differences in efficacy between the different forms of psychotherapy and the different mental disorders? What makes psychotherapy effective? What influence does the therapist have on the outcome of a psychotherapy? Following a systemic perspective that pursues a biopsychosocial vision, in the manualization of a therapeutic protocol, what are the conditions that need to be considered?

In an attempt to answer these questions, it is necessary to consider that a correct assessment of the effectiveness of a psychotherapy implies a regular follow-up activity and the conduct of randomized controlled trials (RCT) which confirm the effectiveness of the treatment from an evidence-based perspective. In this perspective it is necessary to carry out research on efficacy (to demonstrate experimentally that a treatment acts on a specific disorder excluding the influence of other factors), on effectiveness (to evaluate the outcome of psychotherapeutic interventions as they are used in the reality of clinical contexts), and on efficiency (to evaluate the efficiency of the treatment in terms of cost-benefits and real applicability). These studies require a specific methodology and often the manualization of therapeutic protocols. RCT research data are usually reworked in a meta-analysis which calculates the effect size (the difference in standard deviations between experimental and control groups) which provides a general measure of the amplitude of the phenomenon (a Cohen d value of 0.2 corresponds to a limited effect, 0.5 moderate, 0.8 wide, and 1.0 excellent).

Psychoanalysts have for years shown a certain reluctance to subject their clinical work to validation research, but in recent years, under the pressure of the numerous papers published on the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), many RCT studies have been organized on large samples of patients subjected to different psychotherapeutic techniques, short- and long-term psychodynamic ones included (Shedler 2010, 2018). Research into the effectiveness of systemic treatments, despite their complexity, the difficulty of manualizing them, and the number of subjects involved, has also developed considerably since the turn of the century (Carr 2009). This applies to both family, individual, and couple systemic treatments for adult-focused problems (Carr 2014, 2018a; Stratton 2016; Ochs et al. 2020) and for child-focused problems (Carr 2018b).

Collectively, the results of evidence-based research on the outcomes of psychotherapy (especially considering individual psychotherapies of different orientation but neglecting couple, family, or group ones) are set out in an official document of Division 29 of the American Psychological Association (APA 2012) entitled Recognition of Psychotherapy Effectiveness, based on many sources concerning RCT studies, and can be so summarized:

-

1.

Effects of psychotherapy are confirmed and largely significant.

-

2.

They are demonstrated for many mental disorders with variations that are influenced (a) by the severity, chronicity, and complexity of the disorder, rather than by the particular diagnosis and (b) by the characteristics of patients and clinicians and context factors (such as social support), rather than the type of treatment.

-

3.

The beneficial effects of psychotherapy tend to persist and increase over time even after the end of treatment.

-

4.

Efficacy tends to be comparable or superior to that of psychopharmacological treatments, with significantly lower costs and side effects.

-

5.

Psychotherapies reduce disability, morbidity, hospitalizations, and mortality, increasing working skills. This entails a clear reduction in healthcare costs (by 20–30%, with a 17% reduction for patients undergoing psychotherapy compared to a 12.3% increase for those not treated psychologically, leading to a saving, in chronic disorders, of $ 10 for every dollar spent).

-

6.

A strong link between psychological and physical health has been demonstrated, and the validity of programs that consider psychotherapy within basic healthcare has been confirmed.

The same document underlines that psychotherapy is fundamentally based on a valid therapeutic alliance (or working alliance, WA).

The effectiveness of psychotherapy has been demonstrated for a variety of psychological and medical disorders in children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders (panic disorders, generalized anxiety disorders), stress disorder, PTSD, alcohol-related disorders and other addictions, personality disorders, (most) childhood disorders (depression, anxiety, ADHD, conduct disorder) (APA 2012; Wampold 2014).

Data of evidence-based research, therefore, indicate that the different models of psychotherapy, as a whole, produce largely positive results (overall effect size on 475 studies: 0.85) and higher than those of antidepressant pharmacotherapy (Effect size: 0.17–0.31) (Shedler 2010), but that no psychotherapeutic technique has demonstrated a particular superiority over the others (APA 2012; Wampold 2014). In studies where slight differences emerge, the results tend to correspond to the researcher’s preferences and theoretical training rather than to real effects due to the treatment. In particular, empirical research shows that “evidence-based” therapies are weak treatments (Shedler 2018), their benefits are trivial, few patients get well, and even the trivial benefits do not last.

The most related factor to patient satisfaction and the psychotherapy outcome also appears to be the quality of the working alliance (WA) or therapeutic alliance (Safran and Muran 2000; Ardito and Rabellino 2011), a construct derived mainly from the psychoanalytic clinic that refers to non-neurotic or non-transference-related aspects of the psychotherapeutic relationship and that has been defined as a reality-based collaboration between patient and therapist (Greenson 1965). Bordin (1979) described three dimensions: (1) the agreement on the goals of the therapy (goals); (2) the agreement on the tasks to be addressed (tasks); (3) and the development of a bond between patient and therapist based on mutual positive feelings (bond). The latter element is the one most valued by researchers for its similarity to the concept of attachment relationship. WA is perhaps the most studied aspect of the therapeutic process and is recognized as an important nonspecific factor common to many forms of therapy (Shedler 2010, 2018; Ardito and Rabellino, 2011; APA 2012; Baldoni and Campailla 2017).

Other factors associated with higher psychotherapeutic efficacy are also related to the quality of the clinical relationship and the psychological characteristics of the therapist, rather than to the technical aspects (see Fig. 16.1): empathic abilities, sharing of objectives with the patient, taking a positive attitude, and being consistent and authentic. The various meta-analyses of the evidence-based literature (Wampold 2014; Wampold and Imel 2015) have clarified that these are the determining elements (their effect size is higher than 0.2), while, on the contrary, the type of treatment, the adherence to a manualized protocol, or being competent about a particular technique seems to play a decidedly secondary role.

Factors that influence the outcome of psychotherapies. (Source: Wampold, 2014, with the author’s permission)

According to Bruce Wampold (2007, 2012, 2014; Wampold and Imel 2015), one of the most authoritative experts in this field and member of APA division 29, the common factors influencing the effectiveness of psychotherapies are related to some human characteristics (which together constitute the humanistic component psychotherapy), in particular:

-

1.

The tendency to attribute meaning to the world (through interpretation, explanation, attribution of a causal effect, mentalization of oneself and others, organization of experience in the form of narration)

-

2.

The tendency to influence and be influenced by others (i.e., to live in relationship with other people, to act on them, and to be subject to social influence)

-

3.

The tendency to change over time through:

-

(a)

A significant relationship (in particular attachment bonds, such as that between parents and children, between partners of a romantic couple, or between psychotherapist and patient)

-

(b)

The creation of expectations (which explains the therapeutic influence of suggestion, placebo effect, and rituals)

-

(c)

Acquiring a new ability (mastery) (i.e., developing a sense of self-efficacy and control towards events, internal ones in particular, linked to emotional reactions such as fear, anger, anxiety, and depression)

-

(a)

In more recent years, the growing interest in attachment theory has favored the use of this construct as a key for interpreting and measuring the therapeutic relationship (Wallin 2007; Obegi 2008; Holmes and Slade 2018; Baldoni 2018). Research data agree in indicating the safety of the clinician as the greatest predictor of a good therapeutic alliance, while insecure attachment, particularly the one concerned, is related to greater difficulties (Baldoni and Campailla 2017). The particular matching (i.e., the combination) between the attachment pattern of the patient and that of the therapist, which influences the quality of the relationship, the areas explored, the interventions used, and the therapeutic process, and its outcome also plays an important role (Romano et al. 2009; Hill 2015; Baldoni 2008, 2018).

To conclude, evidence-based research has demonstrated the efficacy of psychotherapy in a wide range of pathologies, but for the purposes of treatment, the characteristics of the therapist and the quality of the relationship assume greater importance than the therapeutic technique and the specificity of the diagnosis. However, we need to repeat the caution (above) that very few of the comparisons in the research literature have included systemic couple and family therapies.

It can be legitimately assumed that clinicians who show greater empathic and relational skills develop a solid and lasting working alliance with their patients and are better able to conduct different types of therapies adapting to the personal needs of the different patients, therefore, the most effective beyond their theoretical preparation.

2 Manualization in a Systemic Perspective

How is it possible to use evidence-based research data to develop an appropriate methodology in the study of the effectiveness of treatment and in manualization of psychotherapy? In particular, in a systemic perspective, which methodology should be used in this process? Research data indicate that the quality of the relationship between patients and psychotherapists (in terms of working alliance or attachment safety) is a determining factor, the one most associated with the positive outcome of treatments and the satisfaction of patients and their families. From a systemic perspective, a manualization of a treatment should therefore guide the psychotherapist focusing on these aspects. Some considerations are possible, regarding working alliance, attachment, and mentalization.

3 Assessing Working Alliance and Attachment Matching Between Therapist and Patient

The manualization of a treatment should include tools for assessing working alliance and attachment, considering both patients and psychotherapists. Some useful tools that can be used for this purpose are (Baldoni and Campailla 2017):

-

1.

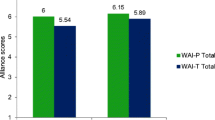

For the assessment of the WA, self-report questionnaires can be used such as the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI), the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (CALPAS), and the Pennsylvania (Penn) Scales (Ardito and Rabellino 2011) completed by the therapist alone, by the patient only, or, more rarely, by both or independent external observers.

-

2.

For the assessment of the attachment of therapists and patients (including their matching), the most used tools are (a) the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1984–1996; Steele & Steele, 2008), a semi-structured interview for the evaluation of the attachment configuration of the therapist and patients; (b) the Patient-Therapist Adult Attachment Interview(PT-AAI) (Diamond et al. 1999), a modified form of the AAI that collects detailed information on the interaction of attachment patterns of therapists and patients; and (c) some self-report questionnaire, like the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale(ECRS) (Brennan et al. 1998) or the Client Attachment to Therapist Scale(CATS) (Mallinckrodt et al. 1995).

Unfortunately, almost all of these tools have been developed for individual assessment. They can therefore be indicated for individual or couple therapies, but they are not specific tools for family or group therapy. One of the few therapeutic models that provide for the assessment of attachment in all family members in a systemic perspective is the Dynamic-Maturational Model of Attachment and Adaptation-integrative family system treatment(DMM-FST) (Crittenden et al. 2014) which pursues the study of attachment in system family therapy, considering different assessment tools in life span. Again, however, the attachment of the therapist is rarely considered (Baldoni 2018).

4 Assessing Mentalization in a Systemic Perspective

The terms mentalization and mentalizing refer to “the mental process by which an individual implicitly and explicitly interprets the actions of himself and others as meaningful on the basis of intentional mental states such as personal desires, needs, feelings, beliefs and reasons” (Bateman and Fonagy 2004, xxi) or, more simply, “the capacity to understand ourselves and others in terms of intentional mental states, such as feelings, desires, wishes, goals and attitudes” (Allen et al. 2008). The term reflective functioning(RF), introduced by Peter Fonagy (Fonagy et al. 1991, 1998), represents the operationalization for research purposes of the concept of mentalization. From a clinical point of view, mentalization and reflective functioning can be considered synonyms. These faculties are acquired in the context of the first attachment relationships and are fundamental for the organization of the self and the affect regulation and give meaning to one’s own and others’ behavior.

Mentalization involves a self-reflective component (relating to the representations of the Self) and an interpersonal component (linked to the representation of others). There is also an explicit and an implicit mentalization (Allen et al. 2008).

Explicit mentalization corresponds to “thinking and speaking of mental states,” both one’s own and others’, is conscious, linked to verbal language, and tends to take on the character of a narrative. It can be more easily learned culturally (through social models and stereotypes) or with experience (in family, with friends, at school, at work, or in psychotherapy), but it can also be imitated or falsified through only apparently mentalizing attitudes.

Implicit mentalization is an intuitive, procedural, automatic, and unconscious mentalization (Allen et al. 2008) and concerns both oneself (sense of self, mentalized affectivity) and others (e.g., manifesting itself by changing shift in conversations or when you spontaneously react to other people’s emotions). An example is when spontaneous nonverbal behavior occurs (a meaningful gaze, a particularly expressive gesture such as caressing or touching one part of the other’s body, for example, the face, a shoulder, a hand, or a leg, with a clear intention to communicate one’s own mental state or an understanding of the other’s mental state. Not all emotional states entail an implicit mentalizing (in some cases one can be overwhelmed by an emotion), and there is no defined border between explicit and implicit mentalization.

Pseudo-mentalization is the apparent ability to reflect which lacks the essential characteristics of true mentalization. The pseudo-mentalizing statements at first glance may appear reflexive, but they are the result of a modality of pretending (ideas seem to have meaning, but in reality they are without depth, they are not connected to each other and the states of minds are not really felt or superficial and stereotyped thoughts or manipulative attitudes (Bateman and Fonagy 2004; Allen et al. 2008; Fearon et al. 2006). They tend to be very selective and selfish.

In conclusion, reflective functioning (mentalization) is the basis of empathy (i.e., awareness of the mental states of the other) and allows to go beyond the external attitude to get to grasp the psychological state that motivated a certain way of acting. In the absence of these functions, therefore, one’s own and others’ behavior remain insignificant. Moreover, mentalization fosters the psychological representation and symbolization of inner states and is therefore crucial for the regulation and control of effects and impulses (including the physiological states related to them) (Bateman and Fonagy 2004).

The concept of mentalization is particularly useful for understanding the clinical process in psychotherapy (Baldoni, 2010). In many cases it is essential that the therapist, by carrying out a reflective functioning, makes the patient perceive that he is reflecting on him considering him in terms of mental states. In the most serious patients, this reflective attitude is more important than interpretation. The patient, reflecting in the thoughts of his therapist, can recognize his mental processes by reaching a higher level of awareness and developing in turn a better reflexive ability. Promoting mentalization in patients and their families is a common goal of most psychotherapies (Michels 2006), and the concept of mentalization therefore offers a key to understanding psychotherapeutic mechanisms and opens new perspectives in the therapy of patients who manifest self-structuring disorders, pathological aggression, empathic difficulties (patients with personality disorders, antisocial and violent patients, alexithymic subjects), and psychological trauma (Holmes 2001; Bateman and Fonagy 2004; Allen et al. 2008; Baldoni 2016).

Specific integrated therapeutic protocols have recently been proposed that promote mentalization using attachment theory as a paradigm and combining psychoanalytic, cognitive-behavioral, and systemic techniques with a possible pharmacotherapy (Jurist et al. 2008; Sadler et al. 2006; Baldoni 2010), such as the Brief Attachment-Base Intervention (BABI) (Holmes 2001), the Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT) (Bateman and Fonagy 2004, 2008; Allen et al. 2008), and the Short-term Mentalization and Relational Therapy (SMART) or Mentalization-Based Family Therapy(MBFT) (Fearon et al. 2006), a mentalization-based protocol for systemic family therapy.

It should also be considered that psychotherapeutic treatments, including those based on mentalization, inevitably aim to increase explicit mentalization abilities above all (Allen et al. 2008; Michels 2006). Because of its spontaneous, unconscious, and procedural nature, in fact, the implicit one is more difficult to identify and modify through direct verbal interventions of an interpretative or cognitive-behavioral type.

The mentalizing or reflective processes have been studied in a psychoanalytic and cognitivist perspective above all as individual characteristics. Peter Fonagy (Fonagy et al. 1998) developed a procedure known as the reflective functioning scale(RF) that measures the subject’s overall reflective capacity in a single dimension (from −1 to 9) based on the analysis of the transcription of the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) or others similar semi-structured interviews derived from the AAI like the Parent Development Interview(PDI) or the Current Relationship Interview(CRI).

Although it has been studied mainly in a psychoanalytic and cognitivist perspective, particularly within the theoretical framework of attachment, mentalization and reflective functioning can be considered systemic concepts (Baldoni 2007, 2009), as they (1) involve a clear interpersonal component (decentralization, understanding of the mind of the other, affective mirroring) and (2) refer to the cybernetic concept of feedback (positive and negative) and to mental states, behaviors, and faculties developed within a relationship as a response to the other. These functions are therefore the expression of a relationship within a system (attachment bond, couple, family, psychotherapy). Pasco Fearon (Fearon et al. 2006), a Fonagy collaborator, has in fact used these concepts to develop a specific mentalization and attachment-based systemic family treatment (SMART or MBFT).

Mentalization can therefore be studied not only as a characteristic of a subject but also as an expression of a system of relationships. The reflective skills manifested by a patient, a family, or a couple are in fact important for the maintenance of well-being, the resolution of conflicts, and the ability to adapt, while their lack can be considered a negative prognostic factor for relationship difficulties and psychological, behavioral, and somatic disorders manifested by the members of the family during their life (Baldoni 2016).

For this reason, the manualization of a treatment in a systemic relational perspective must consider these aspects for the study of the therapeutic process and as proof of the efficacy of the treatment itself. Considering that fostering mentalization processes is an objective of most psychotherapies, why not measure this dimension in the reality of the clinical relationship?

5 The Reflective Function in the Family (RFF)

It is clear to everyone that the mentalization processes are not stable (like an IQ) but vary significantly according to the different relational contexts (work, family, friends, psychotherapy). The Reflective Function in the Family (RFF) (Baldoni 2007, 2009) is a new tool for mentalization assessment during a consultation or family therapy session that can be considered in the systemic manualization of a treatment. RFF aims to measure mentalization not as an individual characteristic but as an expression of an interactive system over time. It provides a useful guide for the clinical intervention and for the study of the therapeutic process and effectiveness during treatment, at the conclusion of this and on the occasion of follow-up sessions.

RFF is the specific version for family therapy of the Mentalization Assessment in Psychotherapy (MAP) (Baldoni 2014) a tool currently under study that evaluates the reflective skills manifested by patients and therapists within a consultation or psychotherapy session (individual also). MAP and RFF are both compatible with various theoretical guidelines and can be used in different theoretical contexts (systemic, psychoanalytic, cognitivist, or cognitive-behavioral).

The assessment of reflective skills (mentalization) through RFF is based on the systematic analysis of verbal (and partially nonverbal) communication as shown in the verbatim full transcription of the audio-video recording of a family therapy session. In this way, family therapy sessions videotaped in the past can also be analyzed. The purpose of the RFF (and the MAP) is not the measurement of the individual mentalization level (for which assessment-specific methodologies like the RF/AAI based on semi-structured interviews have been developed) but is to assess the expression of mentalization within a relationship by detecting the mentalizing statements expressed by therapists and patients during a psychotherapy session.

For the detection of reflective (mentalizing) statements and nonverbal mentalizing expressions, different criteria were taken into consideration:

-

1.

Those indicated by Peter Fonagy, Mary Target, Howard Steele, and Miriam Steele for the assessment of the reflective self (RS) (Fonagy et al. 1995) and of the reflective functioning (RF) (Fonagy et al. 1998; Steele and Steele 2008) through the analysis of the transcripts of the Adult Attachment Interview (RF/AAI)

-

2.

The criteria used by Arietta Slade (Slade et al. 2005) for the assessment of the Parental Reflective Functioning through the Parent Development Interview (Aber et al. 1985) (RF/PDI)

-

3.

The criteria for the assessment of metacognition in a psychotherapy session using the Metacognitive Assessment Scale (MAS) (or Scala di Valutazione della Metacomunicazione, S.Va.M.) (Carcione et al. 1997; Semerari et al. 2003)

The criteria for coding reflective statements with RFF can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Specific references to one’s own or others’ mental states

-

2.

Explicit attempts to interpret behavior based on mental states

-

3.

Awareness of the complex nature of mental states

-

4.

Awareness of possible changes in mental states over time

-

5.

Sensitivity towards the other person’s mental states

-

6.

Procedural manifestations of sensitivity towards mental states (implicit mentalization, expressed with nonverbal behavior)

In cases relating to criteria 1 and 2, the reflective statement, to be counted as valid, must:

-

(a)

refer to a subject (the self, the other or both) who experience the mental state;

-

(b)

highlight a non-generic mental state;(c) refer to a specific situation.

To be considered mentalizing, statements about the complex nature of mental states (criterion 3) and its evolutionary aspects (criterion 4) must be used in order to interpret, explain, or clarify the meaning of a behavior within a specific situation, contributing to the understanding of the event in a nontrivial or generic way. In these cases, it is particularly important to consider sufficiently large sections of the transcript (clusters).

For the application of these criteria, it is necessary to consider that:

-

(a)

The reflective statement must be explicit and complete. An incomplete, interrupted, or partial statement is indicated in parentheses and not counted.

-

(b)

It must refer to specific mental states and contexts and not be generic (“In the family I feel rejected” must not be considered reflective, while “When my parents behave this way, I feel rejected” is to be considered reflective).

-

(c)

It must refer to representations of mental states, not to non-mentalizing judgments or descriptions. Affirmations about thoughts, behaviors, or emotional reactions, if not accompanied by the representation of the subject as thinking, are not considered reflective (“At that time I was desperate” is not considered reflective, because it is not clear if it is a posteriori judgment, while “At that time I felt desperate” is reflective).

-

(d)

Statements that merely repeat another person’s statement are not to be considered reflective (e.g., a family member who repeats a reflective hypothesis formulated by a therapist).

-

(e)

Pseudo-mentalizing (i.e., apparently mentalizing) statements are counted in a specific subscale and do not contribute to the calculation of reflective statements.

-

(f)

The statements referring to mental states current and pertinent to that specific situation are to be considered reflective even if one does not explicitly refer to the awareness of the mental state, since the representation of the self as thinking is implicit (e.g., a mother who during the session addresses her son saying: “I am very angry with you!”). They must manifest themselves as fresh and spontaneous expressions referring to their mental states and can be accompanied by comments regarding their mental functioning and by their awareness of the complexity of their thinking and their discrepancies and contradictions (Metacognition).

-

(g)

The context of the speech must be assessed, considering the previous and subsequent sentences (e.g., if the statement is in relation to a question from the therapist).

In RFF the assessment scores of the reflective functioning statements are distributed in subscales, scales, and total scores (see Fig. 16.2). They are indicated with the letter S (self) if referring to the self, with the letter O (others) if referring to other people, with the initials U (us) if referring to both the self and other people (as in the case where a therapist or family member expresses himself in terms of “we”). The initials H (hypothesis) are added to the reflective statements of the therapists expressed in the form of hypotheses or reflective or circular questions.

RFF coding card (Baldoni 2010)

The T (therapist and possible co-therapist), M (mother), F (father), S (son, 1, 2, 3), and O (other, like grandparents, uncles, friends, new partners) scales are composed of the sum of the scores of two subscales: the Sp (spontaneous) subscale, related to the reflective statements that emerge spontaneously, and the Rq (on request) subscale in which the answers provided to specific requests are counted, usually by a therapist (as in the case of a reflective question). The total scores respectively indicate the total of the therapists’ reflective statements expressed in the form of hypotheses or questions (H) and finally the reflective capacity expressed overall by the family (RFF), by the therapists (TT), and by the therapist/family system (C) in that specific session. The RFF/C index refers to the percentage of total reflective affirmations of the family (RFF) compared to the total of the session (C) and expresses the overall reflective capacity of the family in relation to therapeutic interventions.

Nonverbal expressions of implicit mentalization (Analogical Implicit Mentalization, AIM) are usually detected through a careful viewing of the videotaped session (or in its transcription when the nonverbal aspects have been accurately reported) and are counted in the RFF coding card as mentalizing expressions concerning the self (S/AIM) or the other (O/AIM). Pseudo-mentalizing statements are not considered reflective and are not counted.

Reflective statements, scales, subscales, and total ratios are noted in the RFF coding card (see Fig. 16.2 and 16.3) and transferred in Excel format (Table 16.1) and graphics (Fig. 16.4).

Example of RFF coding completed card. (Baldoni 2010)

The final version of the coding criteria was developed considering the experience of the group of researchers of the Attachment Assessment Lab (Department of Psychology of Bologna) headed by me, who used the pilot version of the RFF in the 3-year period 2009–2011 (Veronica Amadori, Clelia Angelastri, Flavio Casolari, Lucia Colangelo, Sara D’Alessandro, Francesca Del Fabbro, Margherita Dilorenzo, Mattia Minghetti, Laura Nannucci, Micol Natali, Samanta Sagliaschi). The use of the RFF required almost 2 years of training to achieve a coding reliability equal to or greater than 70% (14 family therapies were analyzed, 3 sessions for each therapy). From 2012, the RFF was used in research carried out by the Attachment Assessment Lab in collaboration with the ISCRA Institute of Modena. The results were presented in papers presented at different international congresses (Baldoni 2007; Bassoli et al. 2013).

6 An Example of Systemic Family Treatment Assessed with RFF

The Green familyFootnote 1 requested treatment presenting the problem of the eating behavior disorder of their daughter Lucy, 20 years old. Lucy had been suffering from anorexia since the age of 13 and has been treated for years by an individual psychotherapist who suggested that the family undergo systemic family therapy. Lucy, a student, had a boyfriend at the time but had dropped out of school to pursue sports with her mother.

The first session was attended by the mother (48 years old, employed and semi-professional sportswoman), the father (50 years old, musician), Lucy, and her sister Anne (23 years old, employed).

The therapy was conducted by two therapists (Dr. X and Dr. Y), for a total of 11 sessions on a monthly basis and ended following the significant symptomatic improvement of Lucy and the lesser concern of the parents. The sessions were videotaped and evaluated using the RFF by two reliable coders (trained in a specific course at the Department of Psychology of the University of Bologna). The analysis with the RFF highlighted interesting aspects of the therapeutic process (see Fig. 16.5) and of the techniques adopted by the therapists.

Some key sessions from the beginning to the end of the treatment (I, II, V, and XI), with some transcriptions of video recordings and related RFF coding examples:

-

Session I (present: mother, father, Lucy, and Anne): it was characterized by very few reflective statements from both the family (RFF: 1) and the therapists (TT: 0). Usually this session is dedicated to describing problems and introducing family members.

-

Session II (father is missing): there is an increase in reflective statements from the family (RFF: 6), often at the request of therapists, who however do not make reflective statements throughout the session.

-

T1: Hmm... And you know what concern mom and dad have?

-

Anne: Yes, surely their concern stems from the fact that they hear me and see me less, because I no longer live with them, so they feel less controlled and more worries arise. [Rq, O, 1a] (reflective statement on demand that concerns the self, 1a criterion).

-

Session V (the whole family is present): the reflective statements increase significantly, both those of the family (RFF: 7) and those of the therapists (TT: 3), and the total score of the session (C) is therefore 10. We are in the middle of therapeutic interventions, and therapists use thoughtful and hypothetical questions (Tomm 1988).

-

T1: That you can’t even understand where they come from. With you it is more about hearing things than understanding. You have already tried so much (the mother laughs) that perhaps it is better to follow the track of how you are and how you feel; dad feels more serene because he sees Lucy more serene, Anne feels more serene because she discovered things in Lucy that she didn’t expect, mom is perhaps the one who most difficult accepts the idea that there may be this improvement, this change perhaps because it is due to these ups and downs, to these illusions and perhaps he prefers this change. [Sp, O, 1a, H] (spontaneous and hypothetical reflective statement about self, 1a criterion).

-

Mother: I struggle.

-

T1:What about Lucy? Let’s try to get Lucy off the pedestal and put her in the middle. How does Lucy feel?

-

Lucy: I feel, as my mom said, more convinced and to continue the path I am taking and... [RQ, S, 1a]. (reflective statement on demand, regarding the self, 1a criterion).

-

Session XI (conclusion of the treatment, the whole family is present): the total reflective statements (C: 4) and those of family members (RFF: 3) and therapists (TT: 1) decrease significantly. Lucy no longer manifests worrying symptoms or behaviors, has gradually become autonomous, and continues individual treatment. Sister Anne is dating a boy, mother and father are more serene, and therapists prepare the family for discharge.

-

T1: We have made a path for which I believe this transformed history should be seen..., let’s say, compared to how it was described at the beginning, when you came, in short, it is not a story that at any moment turned upside down (...). Um, I saw you completely changed, didn’t I? [Gen] (generic reflective statement).

Based on this and many other sessions assessed with RFF, some clinical considerations regarding mentalizing in systemic family therapy and the technique of therapists are possible (Baldoni 2007; Bassoli et al. 2013):

-

1.

The first sessions tend to be not very mentalizing, as are dedicated to gathering information on the family and the problem presented.

-

2.

The intermediate sessions are often characterized by a greater number of mentalizing expressions both by the therapist and the family members. Reflexive and hypothetical interventions are frequent. The therapeutic process is underway, the reflexivity between therapists and family increases (Tomm 1988). and the family system tends to change.

-

3.

In the final sessions, dedicated to the restitution of a more adaptive narrative and to the end of the treatment (Sluzki 1992), the mentalizing expressions tend to decrease.

7 Conclusions

Evidence-based research data on the effectiveness of psychotherapies (mainly derived from research on individual treatments) indicate that the factor most associated with the outcome of the treatment is the quality of the clinical relationship. Therefore, a manualization of a treatment, in a systemic perspective, should include tools for the assessment of this dimension (in terms of working alliance, attachment of patients and therapists. and mentalization processes manifested in therapy). Unfortunately, most tools assess these dimensions as individual characteristics. RFF is one of the few tools to evaluate mentalization from a systemic perspective. and its integration in the manualization of a therapeutic protocol can provide very useful information for therapists and to study the effectiveness of treatment.

Notes

- 1.

Names and personal details have been changed to preserve anonymity.

References

Aber, J. L., Slade, A., Berger, B., Bresgi, I., & Kaplan, M. (1985). The parent development interview: Manual and administration procedures. Barnard College, Department of Psychology.

Allen, J. G., Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. W. (2008). Mentalizing in clinical practice. American Psychiatric Press.

APA, American Psychological Association (2012). Recognition of psychotherapy effectiveness.http://www.apa.org/about/policy/resolution-psychotherapy.aspx.

Ardito, R. B., & Rabellino, D. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: Historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(Art. 270), 1–11.

Baldoni, F., & Campailla, A. (2017). Attachment, working Alliance and therapeutic relationship: What makes a psychotherapy work? Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, XLIV(4), 823–846. https://doi.org/10.1421/88770

Baldoni, F. (2007). La Reflective Function in the Family (RFF): una procedura di valutazione della funzione riflessiva in terapia familiare. In Proceedings National Congress of the Italian Psychology Association (AIP) (Perugia Sept. 28–30, 2007) (pp. 1–9). Perugia: AIP.

Baldoni, F. (2008). L’influenza dell’attaccamento sulla relazione clinica: collaborazione, collusione e fallimento riflessivo. Maieutica, 27–30 (June 2007–June 2008), 57–72.

Baldoni, F. (2009). Reflective function in the family (RFF), Manual (v. 1.2). Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, University of Bologna.

Baldoni, F. (2010). Mentalization, clinical relationship and therapeutic process. Paper presented at the International Congress Rehabilitation processes: affects and neuroscience (Bologna, Nov. 6, 2010).

Baldoni, F. (2014). Mentalization Assessment in Psychotherapy (MAP). Manual (v. 1.0). Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, University of Bologna.

Baldoni, F. (2016). Psychological trauma and somatization processes: A complex relationship. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology MJCP, 4(Suppl. 2 A), 51.

Baldoni, F. (2018, June). The clinical matching: interactions between patient’s and therapist’s attachment strategies in a DMM perspective. Paper presented at IASA’s 10-Year Celebration (Florence, June 12–14, 2018).

Bassoli, F., Baldoni, F, & Campanella, V. (2013, Sept.). Funzione trasformativa e mentalizzazione in terapia familiare: un modello di valutazione del processo terapeutico. Paper presented at the Second Congress of the Italian Society of Psychotherapy (SIPSIC) (Paestum, 26–28 September 2013).

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2008). 8-year follow-up of patients treated for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 631–638.

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2004). Psychotherapy of borderline personality disorders: Mentalization based treatment. Oxford University Press.

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16, 252–260.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

Carcione, A., Falcone, M., Magnolfi, G., & Manaresi, F. (1997). La funzione metacognitiva in psicoterapia: Scala di Valutazione della Metacognizione (S.Va.M.). Psicoterapia, 9, 91–107.

Carr, A. (2009). The effectiveness of family therapy and systemic interventions for adult-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 31, 3–45.

Carr, A. (2014). The evidence base for couple therapy, family therapy and systemic interventions for adult-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 158–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12033

Carr, A. (2018a). Couple therapy, family therapy and systemic interventions for adult-focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41, 492. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12225

Carr, A. (2018b). Family therapy and systemic interventions for child-focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41, 153. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12226

Crittenden, P., Dallos, R., Landini, A., & Kozlowska, K. (2014). Attachment and family therapy. Open University Press (McGraw-Hill Education).

Diamond, D., Clarkin, J., Levy, K., Levine, H., Kotov, H., & Stovall-McClough, C. (1999). The patient therapist adult attachment interview (PT-AAI). Unpublished manuscript, New York: The City University of New York, Department of Psychology.

Fearon, P., Target, M., Sargent, J., Williams, L. L., McGregor, J., Bleiberg, E., & Fonagy, P. (2006). Short-term mentalization and relational therapy (SMART): An integrative family therapy for children and adolescents. In J. G. Allen & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of mentalization-based treatment (pp. 201–222). Wiley.

Fonagy, P., Steele, H., Moran, G. S., Steele, M., & Higgitt, A. (1991). The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 13, 200–217.

Fonagy, P., Steele, M., Steele, H., Leigh, T., Kennedy, R., Mattoon, C., & Target, M. (1995). Attachment, the reflective self and borderline states. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, & J. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment, theory social, development and clinical perspectives (pp. 233–278). Analytic Press.

Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1998). Reflective-functioning manual, version 5, for application to adult attachment interviews. University College.

George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1984-1996). Adult Attachment Interview Protocol. Unpublished manuscript. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley.

Greenson, R. R. (1965). The working alliance and the transference neurosis. Psychoanalitic Quarterly, 34, 155–179.

Hill, D. (2015). Affect regulation theory: A clinical model. W. W. Norton.

Holmes, J. (2001). The search for the secure base: Attachment theory and psychotherapy. Routledge.

Holmes, J., & Slade, A. (2018). Attachment in therapeutic practice. Sage.

Jurist, E. L., Slade, A., & Bergner, S. (Eds.). (2008). Mind to mind. Infant research, neuroscience, and psychoanalysis. Other Press.

Mallinckrodt, B., Gantt, D. L., & Coble, H. M. (1995). Attachment patterns in the psychotherapy relationship: Development of the client attachment to therapist scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 307–317.

Michels, R. (2006). Epilogue: Thinking about mentalization. In J. G. Allen & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of Mentalization-based treatment (pp. 327–333). Wiley.

Obegi, J. H. (2008). The development of the client-therapist bond through the lens of attachment theory. Psychotherapy, Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45(4), 431–446.

Ochs, M., Borcsa, M., & Schweitzer, J. (Eds.) (2020). Systemic research in individual, couple, and family therapy and counseling. European Family Therapy Association Series, Switzerland: Springer.

Romano, V., Janzen, J., & Fitzpatrick, M. (2009). Volunteer client attachment moderates the relationship between trainee therapist attachment and therapist interventions. Psychotherapy Research, 19(6), 666–676.

Sadler, L. S., Slade, A., & Mayes, L. C. (2006). Minding the baby: A Mentalization-based parenting program. In J. G. Allen & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of Mentalization-based treatment (pp. 269–288). Wiley.

Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance. A relational treatment guide. Guilford Press.

Semerari, A., Carcione, A., Dimaggio, G., Falcone, M., Nicolò, G., Procacci, M., & Alleva, G. (2003). How to evaluate metacognitive functioning in psychotherapy? The metacognition assessment scale and its applications. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 10, 238–261.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98–109.

Shedler, J. (2018). Where is the evidence for “evidence-based” therapy? Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 41, 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2018.02.001

Slade, A., Bernbach, E., Grienenberger, J., Levy, D., & Locker A. (2005). Addendum to Reflective Functioning Scoring Manual (Fonagy, Steele, Steele & Target, 1998). For use with the Parent Development Interview (PDI; Aber, Slade, Berger, Bresgi, & Kaplan, 1985; PDI-R; Slade, Aber, Berger, Bresgi & Kaplan, 2003) (Version 2.0). Unpublished manuscript. The City College and Graduate Center of the University of New York.

Sluzki, C. E. (1992). Transformations: A blueprint for narrative changes in therapy. Family Process., 31(3), 217–230.

Steele, H., & Steele, M. (2008). Clinical applications of the adult attachment interview. The Guilford Press.

Stratton, P (2016). The evidence base of family therapy and systemic practice. Association for Family Therapy, UK.

Tomm, K. (1988). Interventive interviewing: Part III. Intending to ask lineal, circular, reflexive or strategic questions? Family Process, 27, 1–15.

Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

Wampold, B. E. (2007). Psychotherapy: The humanistic (and affective) treatment. American Psychologist., 82, 857–873.

Wampold, B. E. (2012). Humanism as a common factor in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 445–449.

Wampold, B. E. (2014, Sept). What makes psychotherapy work? The humanistic elements! Paper presented at X National Congress SPR Italy Area Group (Padua, Sept. 12–14, 2014).

Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Baldoni, F. (2021). Working Alliance, Attachment, and Mentalization as Relational Indexes for a Systemic Manualization of Psychotherapy. In: Mariotti, M., Saba, G., Stratton, P. (eds) Handbook of Systemic Approaches to Psychotherapy Manuals. European Family Therapy Association Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73640-8_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73640-8_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-73639-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-73640-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)