Abstract

There have been a number of landmark trials that have revolutionized the surgical management of breast cancer. We review studies that provided the foundation for the movement from radical mastectomy to breast-conserving surgery and that have transformed the management of the axilla from axillary dissection to sentinel node biopsy. Indeed, over the last several decades, there has been a progressive movement toward minimizing the extent of surgical intervention in breast cancer management, with greater integration of a multidisciplinary approach including medical and radiation oncology. A number of advances have been made to optimize margin clearance, improve postoperative cosmetic outcomes, and minimize morbidity; we review the evidence to support these techniques. Finally, we provide a glimpse into ongoing studies that are poised to disrupt the practice of breast cancer surgery even further going forward.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Significant advances have been made in nearly every aspect of the multidisciplinary management of breast cancer patients over the last several decades. Indeed, breast cancer surgery has been revolutionized by a number of key studies (Table 2.1) and continues to morph in an era of increasing collaboration between disciplines. This chapter will review the tremendous progress made in the field of breast cancer surgery and milestone studies that have paved the way for this. It should be noted that there have been many other studies that have also been critical to our progress, and all studies add to our knowledge and have been building blocks for progress; however, it is impossible to include all studies in a single chapter. Hence we have focused on large randomized controlled trials that have been practice-changing.

2 Transformation of Surgery for Tumor Extirpation

2.1 From Radical Mastectomy to Total Mastectomy

One of the first landmark trials that spurred on the modern era of breast cancer surgery was the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-04 [1]. This study stratified patients into node-positive versus node-negative groups and randomized patients to undergo either radical mastectomy, which had theretofore been the staple of breast cancer surgery and involved removal of the breast, pectoral muscles, and axillary lymph nodes, or total mastectomy (with or without radiation) in which the muscle and lymph nodes were left intact (Fig. 2.1). With over 25 years of follow-up, no difference was found between the two groups in terms of either overall or disease-free survival. These data allowed for a dramatic shift in the surgical management of breast cancer, sparing patients from the disfiguring sequelae of removing the pectoral muscles. In addition, the finding that removing axillary lymph nodes did not affect survival laid the foundation for lymph node-sparing procedures to come.

2.2 From Total Mastectomy to Breast-Conserving Surgery

Perhaps one of the greatest advances in breast surgery came from the realization of the survival equivalence of breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy. In the NSABP B-06 [2] and Milan [3] trials, women were randomized to undergo either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery. Both of these studies provided robust evidence that these two strategies were equivalent in terms of survival. Furthermore, the NSABP B-06 trial, which randomized patients having breast-conserving surgery to undergo either adjuvant radiation therapy or not, also defined the need for radiation therapy to improve local control. These trials were paradigm shifting as they provided level 1 evidence to allow surgeons to preserve the breast and further highlighted the need for multidisciplinary collaboration. With advances in screening and early detection, breast-conserving surgery has become the mainstay of surgical management.

2.3 Making More Patients Candidates for Breast-Conserving Surgery

With increasing collaboration between surgery and medical oncology, the question of timing of surgery vis-à-vis chemotherapy was raised. Some argued that giving neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery would be an optimal strategy, as this would prioritize the reduction of the systemic burden of disease. Others argued that primary surgery would be better as this would remove the bulk of the cancer. The NSABP B-18 trial [4] randomized patients with operable breast cancer to either receive four cycles of doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide followed by surgery or surgery followed by the same chemotherapy regimen. With an endpoint of survival, this trial found no significant difference between the two arms. In addition, it was found that the degree of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy could predict overall survival and further that neoadjuvant chemotherapy rendered more patients eligible for breast-conserving surgery [5]. As a result, the approach of treating patients with neoadjuvant therapy has become a mainstay in the surgeon’s arsenal for converting patients with large tumors who are only candidates for mastectomy into patients with smaller tumors who may then become candidates for breast-conserving surgery.

2.4 Improving Techniques to Reduce Margin Positivity

A critical element of breast-conserving surgery is attainment of a negative margin, as positive margins have been associated with higher locoregional recurrence rates [6]. While there has been much debate over what constitutes a clear margin, a recent consensus statement [7] concluded that the definition of “no tumor at ink,” which was used in the NSABP B-06 trial, should be used as the benchmark. Despite surgeons’ best efforts, the rate of positive margins after breast-conserving surgery has been reported to be 20–40%. A number of techniques have been evaluated to lower this rate; randomized trials, however, have been few (Table 2.2).

Surgeons rely on preoperative imaging in their surgical planning, but the value of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in improving margin clearance had been contested. There have been two randomized controlled trials that have evaluated the impact of this technology in reducing positive margin rates. While the COMICE trial [8] found no difference between the two arms, the MONET trial [9] paradoxically demonstrated an increase in positive margins associated with the use of preoperative MRI. An ongoing American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG)/American College of Radiology Imaging Network trial seeks to further evaluate the impact of MRI on surgical outcomes.

Other studies have evaluated the impact of intraoperative imaging, frozen section, novel technology, and/or oncoplastic techniques, which remove segments of tissue often extending from the skin to the chest wall, to improve positive margin rates. In terms of lesion localization, Postma et al. found that radioactive occult lesion localization (ROLL) did not reduce positive margin rates despite more tissue being removed [10]. Others have found that intraoperative ultrasound [11, 12] and/or use of novel technology such as MarginProbe (Dune Medical) [13] may result in lower positive margin rates. More recently, there have been a number of randomized controlled trials evaluating the routine resection of cavity shave margins, all of which have found that this simple technique can reduce positive margins and re-excisions by at least 50% [14, 15].

2.5 Making Mastectomy more Cosmetically Acceptable

While the NSABP B-06 and Milan [3] trials had demonstrated that breast conservation and mastectomy were equivalent in terms of survival, some patients may not be eligible for or may choose to have mastectomy. Surgical techniques have evolved beyond the conventional mastectomy which leaves patients flat-chested to include techniques such as skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy. While there have not been randomized controlled trials to assess these newer techniques, a number of large cohort studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that skin-sparing mastectomies are oncologically equivalent to conventional mastectomies [16]. Other studies have also found that the ability to offer patients immediate reconstruction often results in improved body image and quality of life for breast cancer patients.

3 Transformation of Lymph Node Evaluation and Management

3.1 From Axillary Dissection to Sentinel Node Biopsy

It was clear from the NSABP B-04 [1] and Milan [3] trials that removing axillary nodes did not impart a survival benefit. The INT 09/98 trial [17] randomized women aged 35–65 who had clinically T1N0 cancers to quadrantectomy with axillary node dissection vs. quadrantectomy alone. Similar to the earlier trials, they too found that axillary node dissection did not confer any survival advantage. However, knowledge of lymph node status did result in more patients being treated with chemotherapy (51.5% vs. 35.5%, p < 0.001); hence, the prognostic information was useful for clinicians.

The purpose of lymph node evaluation was twofold: for staging and for local control. The popularization of sentinel node biopsy in melanoma [18] laid the path for the technique to be tried in breast cancer, and early work by Giuliano [19], Krag [20], and others confirmed the fact that this procedure was feasible in breast cancer. Large cohort studies, like the Louisville Breast Sentinel Node Study [21], which asked surgeons to perform a sentinel node biopsy followed by a routine axillary dissection, provided a plethora of data regarding the technique. In particular, they were able to show that surgeons were able to not only identify the sentinel node but that the false negative rate was fairly low. The NSABP B-32 [22] was a randomized controlled trial that confirmed these findings. Randomizing patients between routine axillary dissection and axillary dissection only if the sentinel node was positive, this study found no difference in survival nor in locoregional recurrence. Hence, sentinel node biopsy became standard of care.

3.2 Sentinel Node Biopsy in the Setting of Neoadjuvant Therapy

With the increasing use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the question of timing of sentinel node biopsy came into question. A number of studies had indicated that the false-negative rate of this technique was higher if done after neoadjuvant chemotherapy [23], prompting some surgeons to opt to do the sentinel node biopsy prior to the initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Other studies, however, felt that sentinel node biopsy was feasible and accurate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy [24]. They argued that doing so obviated the need for two surgical procedures and could spare some patients an unnecessary axillary dissection. The ACOSOG 1071 [25] and SENTINA [26] trials (Fig. 2.2), each using a slightly different schema, were designed to settle this debate. The identification rates were acceptable in both studies (92.7% and 80.8% for the ACOSOG 1071 and SENTINA trials, respectively). False-negative rates after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were also thought to be acceptable, especially if two or more sentinel nodes were removed.

3.3 Avoiding Axillary Dissection in Node-Positive Patients

Often, the sentinel nodes are the only ones harboring cancer, and a number of studies had found the chances of non-sentinel node metastases are approximately 20–40%. There would be little benefit to performing an axillary dissection in these cases; despite a number of nomograms and clinical prediction rules that have been formulated to predict non-sentinel node metastases, none of these is perfect. In the current era where the majority of cancers are found early and where there is nearly ubiquitous use of systemic therapy, some wondered if completion axillary node dissection was truly necessary. Given that radiation therapy had been shown to improve local recurrence in the breast for patients undergoing breast conservation, some considered whether axillary radiotherapy may provide adequate local control in sentinel node-positive patients. Indeed, the tangent fields used in whole breast radiation therapy in patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy tend to cover the lower two thirds of the axilla. Hence, investigators began to ask whether axillary dissection was always mandatory in sentinel node-positive patients.

A number of clinical trials, including the ASCOSOG Z-0011 [27, 28], IBCSG 23-01 [29], and AMAROS [30] studies, sought to answer this question. Each of these had different inclusion and exclusion criteria and randomization arms, yet the results were remarkably similar (Table 2.3). Confirming the results of the NSABP B-04, none found a difference in survival; more importantly, the axillary recurrence rates in all arms of all trials were remarkably low. Of note, the AMAROS trial also found the rate of lymphedema was less after axillary radiation than after axillary dissection (5% vs. 13% based on >10% increase in arm circumference at 5 years, p = 0.0009). Hence, many surgeons have changed their practice and no longer routinely perform axillary dissections in all sentinel node-positive patients.

4 Future Directions

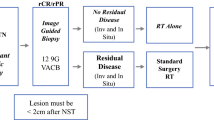

As the genomic revolution continues, and we move toward more personalized therapies, it is undoubtable that surgery will move in this direction as well. Already, there are studies ongoing that ask the question whether all breast cancer patients require surgery, thus furthering the movement from radical surgery to more minimalist approaches. The ongoing COMET trial seeks to understand whether patients with small low-to-intermediate-grade DCIS lesions can be treated with endocrine therapy alone, and the Exceptional Responder trial is evaluating whether patients with her-2-neu-positive and triple-negative breast cancer who have an imaging-guided biopsy complete response after neoadjuvant therapy can be observed without surgery. On the other hand, some trials are evaluating the role for breast cancer surgery in the setting of metastatic disease. As large paradigm-shifting studies are done, there will be a metamorphosis in the surgical management of breast cancer that will rival the significant progress that has occurred over the last several decades.

References

Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):567–75.

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–41.

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–32.

Wolmark N, Wang J, Mamounas E, Bryant J, Fisher B. Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer: nine-year results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;30:96–102.

Fisher B, Brown A, Mamounas E, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(7):2483–93.

Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, Morrow M. The association of surgical margins and local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(3):717–30.

Moran MS, Schnitt SJ, Giuliano AE, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology consensus guideline on margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stages I and II invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(3):704–16.

Turnbull L, Brown S, Harvey I, et al. Comparative effectiveness of MRI in breast cancer (COMICE) trial: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):563–71.

Peters NH, van Esser S, van den Bosch MA, et al. Preoperative MRI and surgical management in patients with nonpalpable breast cancer: the MONET - randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2011;47(6):879–86.

Postma EL, Verkooijen HM, van Esser S, et al. Efficacy of 'radioguided occult lesion localisation' (ROLL) versus 'wire-guided localisation' (WGL) in breast conserving surgery for non-palpable breast cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(2):469–78.

Rahusen FD, Bremers AJ, Fabry HF, van Amerongen AH, Boom RP, Meijer S. Ultrasound-guided lumpectomy of nonpalpable breast cancer versus wire-guided resection: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(10):994–8.

Krekel NM, Haloua MH, Lopes Cardozo AM, et al. Intraoperative ultrasound guidance for palpable breast cancer excision (COBALT trial): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(1):48–54.

Schnabel F, Boolbol SK, Gittleman M, et al. A randomized prospective study of lumpectomy margin assessment with use of MarginProbe in patients with nonpalpable breast malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1589–95.

Chagpar AB, Killelea BK, Tsangaris TN, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cavity shave margins in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):503–10.

Jones V, Linebarger J, Perez S, et al. Excising additional margins at initial breast-conserving surgery (BCS) reduces the need for re-excision in a predominantly African American population: a report of a randomized prospective study in a public hospital. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(2):456–64.

Lanitis S, Tekkis PP, Sgourakis G, Dimopoulos N, Al Mufti R, Hadjiminas DJ. Comparison of skin-sparing mastectomy versus non-skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):632–9.

Agresti R, Martelli G, Sandri M, et al. Axillary lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with T1N0 breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial (INT09/98). Cancer. 2014;120(6):885–93.

Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill : 1960). 1992;127(4):392–9.

Giuliano AE, Dale PS, Turner RR, Morton DL, Evans SW, Krasne DL. Improved axillary staging of breast cancer with sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222(3):394–9. discussion 399-401

Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT. Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol. 1993;2(6):335–9. discussion 340

McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternative to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2560–6.

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–33.

Nason KS, Anderson BO, Byrd DR, et al. Increased false negative sentinel node biopsy rates after preoperative chemotherapy for invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89(11):2187–94.

Breslin TM, Cohen L, Sahin A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is accurate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18(20):3480–6.

Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1455–61.

Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):609–18.

Giuliano AE, McCall L, Beitsch P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):426–32. discussion 432-423

Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(6):569–75.

Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):297–305.

Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1303–10.

Further Reading

Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1455–61.

Chagpar AB, Killelea BK, Tsangaris TN, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cavity shave margins in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):503–10.

Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22,023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1303–10.

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–41.

Fisher B, Brown A, Mamounas E, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and bowel project B-18. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1997;15(7):2483–93.

Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):567–75.

Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):297–305.

Giuliano AE, McCall L, Beitsch P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):426–32. discussion 432-423

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–33.

Krekel NM, Haloua MH, Lopes Cardozo AM, et al. Intraoperative ultrasound guidance for palpable breast cancer excision (COBALT trial): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(1):48–54.

Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):609–18.

Lanitis S, Tekkis PP, Sgourakis G, Dimopoulos N, Al Mufti R, Hadjiminas DJ. Comparison of skin-sparing mastectomy versus non-skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):632–9.

McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternative to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2560–6.

Peters NH, van Esser S, van den Bosch MA, et al. Preoperative MRI and surgical management in patients with nonpalpable breast cancer: the MONET - randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 2011;47(6):879–86.

Postma EL, Verkooijen HM, van Esser S, et al. Efficacy of ‘radioguided occult lesion localisation’ (ROLL) versus ‘wire-guided localisation’ (WGL) in breast conserving surgery for non-palpable breast cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(2):469–78.

Rahusen FD, Bremers AJ, Fabry HF, van Amerongen AH, Boom RP, Meijer S. Ultrasound-guided lumpectomy of nonpalpable breast cancer versus wire-guided resection: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(10):994–8.

Schnabel F, Boolbol SK, Gittleman M, et al. A randomized prospective study of lumpectomy margin assessment with use of MarginProbe in patients with nonpalpable breast malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1589–95.

Turnbull L, Brown S, Harvey I, et al. Comparative effectiveness of MRI in breast cancer (COMICE) trial: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):563–71.

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chagpar, A.B. (2021). Milestone Studies in Breast Cancer Surgery. In: Rezai, M., Kocdor, M.A., Canturk, N.Z. (eds) Breast Cancer Essentials. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73147-2_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73147-2_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-73146-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-73147-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)