Abstract

Self-criticism has been identified as a core dimension of depressive experience. At the same time, the ability to regulate self-esteem and maintain a realistic and positive view of the self is an important aspect of personality functioning. Thus, the functional domain of self-criticism overlaps with both depression and personality dysfunction. The chapter will first provide an overview of commonalities and differences between self-criticism, depression, and personality dysfunction. Empirical studies are reviewed to shed light on the overlap as well as the unique aspects of the three constructs. A particular focus will be placed on the impact of personality dysfunction from a perspective of the Structural Integration Axis of the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis System (OPD-2), which highly overlaps with the levels of functioning from the DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality Disorders. Secondly, we review clinical theory and empirical research on self-criticism as a predictor of psychotherapy outcome. The findings demonstrate that pronounced self-criticism has a meaningful impact on the treatment process and needs to be addressed specifically and adaptively for successful outcomes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 The Construct of Self-Criticism

A critical view of the self is highly prevalent in depression. As early as Freud’s seminal writing Mourning and Melancholia, he described the phenomenon of self-criticism as moralistic superego attacks on the ego (Freud, 1917). Freud further described the characteristics of the depressive experience, already alluding to a self-critical stance therein:

The distinguishing mental features of melancholia are a profoundly painful dejection, cessation of interest in the outside world, loss of the capacity to love, inhibition of all activity, and a lowering of the self-regarding feelings to a degree that finds utterance in self-reproaches and self-revilings, and culminates in delusional expectation of punishment (emphasis added, p. 244).

A more detailed examination of the construct of self-criticism later occurred in Sid J. Blatt’s two-polarities model of personality development (Blatt, 1974, 2006; Blatt & Zuroff, 1992). In his cognitive-developmental theory, he adopted the idea of two very fundamental psychological dimensions – interpersonal relatedness and self-definition – and linked them to variations in normal personality development and to differences in psychopathology. According to Blatt, normal personality development evolves through a complex dialectic interaction between relatedness (the development of increasingly mature, intimate, mutually satisfying, reciprocal, interpersonal relationships), and self-definition (the development of an increasingly differentiated, integrated, realistic, essentially positive sense of self or identity) across the lifespan. Developmental disruptions are assumed to cause a defensive, markedly exaggerated preoccupation with one of these basic configurations at the expense of the other. These imbalances might be mild as in normal personality variations or more distinct, resulting in severe personality pathology.

Blatt (2008) coined the term self-criticism to refer to an exaggerated emphasis on the developmental line of self-definition. Thus, self-critical individuals are particularly concerned with issues of self-definition such as self-worth, autonomy, and self-control, while they neglect interpersonal relationships. They can be very competitive, driven by high ambitions, perfectionism, and an effort to avoid failures. At the same time, they cannot feel lasting satisfaction in reaction to successes and thus permanently raise the bar for achievements (Blatt, 1995, 1998; Blatt, Shahar, & Zuroff, 2001). Furthermore, self-critical individuals fear to be criticized by others and to lose others’ appreciation. As a consequence, they frequently experience feelings of unworthiness, failure, guilt, inferiority, and shame (Blatt & Luyten, 2009; Whelton & Greenberg, 2005).

In a similar vein, the cognitive school of psychotherapy postulated two basic dimensions of vulnerability to depression that can be related to Blatt’s conceptualizations of relatedness and self-definition (Beck, 1983). While sociotropy refers to a person’s tendency to focus on interpersonal relationships, the fear of being disappointed or abandoned, and includes wishes for intimacy, acceptance, and support, autonomy refers to an individual’s need for independence and control, the fear of personal failure or defeat, and associated self-reproaches. Although measures of sociotropy correlate with interpersonal relatedness, autonomy does not converge with Blatt’s understanding of self-criticism (Blaney & Kutcher, 1991; Rude & Burnham, 1993). As opposed to self-criticism, autonomy implies rather positive than negative premorbid self-evaluations and can be understood as a construct emphasizing aspects of counterdependency rather than unrelenting self-scrutiny (Blaney & Kutcher, 1991; Zuroff, Mongrain, & Santor, 2004). Thus, even though both two-polarities models overlap significantly, Blatt, Quinlan, Pilkonis, and Shea (1995) defined the construct of self-criticism more narrowly in terms of negative self-evaluations associated with active self-bashing. While not explicitly using the term self-criticism, the cognitive approach still implies the concept of self-critical thoughts and beliefs within Beck’s conceptualization of the depressive triad (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), which was formulated even before the idea of the sociotropy-autonomy dichotomy emerged. The depressive triad postulates three types of negative automatic thoughts present in depression: negative views about (1) the self, (2) the world, and (3) the future. The negative views about the self imply self-critical thoughts such as “I am worthless and inadequate,” which are assumed to be activated in specific situations that trigger the underlying (self-critical) core belief (Beck & Alford, 2009).

1.1 Development of Self-Criticism

Within psychodynamic as well as in cognitive approaches, self-criticism is thought to develop as a result of repetitive, early life experiences with significant others, which lead to the development of mental representations or cognitive schemas (Beck, 1996; Blatt, 1974). In line with psychoanalytic object relations theories, Blatt and colleagues (Blatt, 1974; Blatt & Lerner, 1983) assume that early parent-child interactions lead to the formation of mental representations of self and others, which gain complexity throughout the life span and which are composed of affective, cognitive, and motivational features. Specifically, self-critical traits are assumed to originate in the experience of children with parental criticism in a harsh and punitive family environment (Flett, Hewitt, Oliver, & Macdonald, 2002). Similarly, Beck (1967) attributes the development of negative core beliefs and cognitions about the self to critical and disapproving caregivers. Later on, he also spoke of modes or schemas with cognitive, affective, behavioral, and motivational elements that have their origin in early childhood experience and become more elaborate and abstract over time (Beck, 1996). Empirical associations between self-criticism and childhood experiences linked a self-critical stance with parental rejection, overprotection, and unfairness (Campos, Besser, & Blatt, 2013; Irons, Gilbert, Baldwin, Baccus, & Palmer, 2006; Katz & Nelson, 2007).

The assumptions that the predisposition for self-criticism is formed in early infancy and that the cognitive-affective mental structures underlying self-criticism differentiate over the course of development raise the question of whether self-criticism should be rather understood as a trait-like construct or as a more variable state. While Blatt originally spoke of self-criticism as a relatively stable trait, which is however amenable to change within psychotherapy (Blatt & Behrends, 1987), together with colleagues, he later elaborated on a state-trait model of self-criticism (Zuroff, Blatt, Sanislow III, Bondi, & Pilkonis, 1999). This model posits that the availability (i.e., content and structure) of self-critical representations might be rather stable, while the accessibility of these representations can fluctuate due to current mood, social context, and biological factors. Empirical support for this model was recently provided by Zuroff, Sadikaj, Kelly, and Leybman (2016), who showed that self-criticism displayed both trait-like variance between persons and daily fluctuations around individuals’ mean scores. Within cognitive theory at first sight, self-criticism is conceptualized as a rather transient set of thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes toward the self as part of the depressive triad (Beck et al., 1979). However, from the very beginning, Beck defined core beliefs as relatively stable cognitive patterns, and with the adaption of his theory and the introduction of modes that entail cognitive, affective, behavioral, and motivational elements, he moved even closer to a theory of personality development (Beck, 1996). Hence, within both the psychodynamic and cognitive tradition, self-criticism can refer to a relatively stable trait as well as to state-like components such as self-critical automatic thoughts or attitudes.

1.2 Measurement of Self-Criticism

The different approaches toward self-criticism described above are also visible in the multiplicity of available assessment instruments. To date, self-criticism is typically measured by self-report questionnaires. One of the most extensively used scales assessing self-criticism, the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ), was developed in the research group around Blatt in the mid-1970s (Blatt, D’Afflitti, & Quinlan, 1976). The DEQ self-criticism subscale includes items that reflect a discrepancy between a person’s self-image and his or her ideals as well as an associated active self-bashing. Item examples are as follows: “I often find that I don’t live up to my own standards or ideals,” “There is a considerable gap between how I am now and how I would like to be,” and “I tend to be very self-critical.” Another widely used scale for self-criticism, the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS; Weissman & Beck, 1978), is based on Beck’s conception of cognitive dysfunctions and was developed to assess pervasive negative attitudes of depressed people toward the self. Item examples are as follows: “If I fail at my work, then I am a failure as a person” and “If I do not do as well as other people, it means I am an inferior human being.” More recent instruments try to distinguish between different subtypes of self-criticism (Gilbert, Clarke, Hempel, Miles, & Irons, 2004; Thompson & Zuroff, 2004). For example, the Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS; Gilbert et al., 2004) differs between a component of self-criticism that relates to dwelling on mistakes and a sense of inadequacy (inadequate self; e.g., “I remember and dwell on my failings” or “There is a part of me that feels I am not good enough”) and a second, more aggressive component that relates to the urge to hurt the self and feel disgust or hate toward the self (hated self; e.g., “I have become so angry with myself that I want to hurt or injure myself” or “I have a sense of disgust with myself”).

1.3 Perfectionism and Self-Esteem

Self-criticism overlaps with other constructs related to self-evaluation such as perfectionism and self-esteem. In the past, perfectionism and self-criticism were even used interchangeably or merged into the term self-critical perfectionism (Blatt, Zuroff, Hawley, & Auerbach, 2010; Blatt et al., 1995; Shahar, Blatt, & Zuroff, 2007). The work of Dunkley and colleagues was helpful with regard to disentangling the confusion of terms (Dunkley & Blankstein, 2000; Dunkley, Blankstein, Masheb, & Grilo, 2006; Dunkley, Zuroff, & Blankstein, 2006). They found that different measures of perfectionism and self-criticism load on two higher-order dimensions they called personal standards perfectionism and self-critical or evaluative concerns perfectionism. While personal standards perfectionism refers to the setting of and striving for high standards for oneself, self-critical perfectionism refers to overly critical evaluations of one’s own behavior, an inability to derive satisfaction from successful performance, and chronic concerns about others’ criticism and expectations. Based on findings that associated self-critical perfectionism consistently with psychopathology, while personal standards showed weak or nonexistent associations with psychopathology (Dunkley, Blankstein, et al., 2006; Dunkley, Zuroff, & Blankstein, 2006; Stoeber & Otto, 2006), it was concluded that the setting of and striving for high standards is not in itself pathological but that the tendency to critically evaluate the self is pathological and maladaptive. The researchers further found the DEQ self-criticism subscale to be the primary indicator of the self-critical perfectionism dimension (Dunkley, Zuroff, & Blankstein, 2003). Thus, most researchers in the field view self-critical perfectionism and self-criticism as identical, whereas the construct of perfectionism involves further facets such as personal standards (Dunkley, Zuroff, & Blankstein, 2006; Shahar, 2015).

The content overlap between self-criticism and self-esteem is also worth a consideration. Self-esteem is one of the most widely investigated personality and self-concept constructs in psychology (Baumeister, 1993; Hewitt, 2002; Kernis, 2006; Rosenberg, 1965; Swann & Bosson, 2010). The first influential definition of self-esteem was formulated by William James (1890), who viewed self-esteem in terms of the ratio of successes to pretentions in important areas of life. He argued that self-esteem becomes visible in the gap between the real self and the ideal self. This definition comes very close to the items of the DEQ self-criticism subscale that reflect a discrepancy between a person’s self-image and his or her ideals. Later approaches to self-esteem stressed the aspect of personal worth and the judgment of the value of the self (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, & Robins, 2011; Kernis & Waschull, 1995; Rosenberg, 1965; Sedikides & Gress, 2003). For example, Rosenberg (1965), one of the most prominent theoreticians in the field of self-esteem, stated that self-esteem refers to an individual’s overall evaluation of his or her worth as a person. This cognitive self-appraisal in self-esteem is accompanied by an emotional experience toward the self (Crocker & Park, 2012; Leary & Baumeister, 2000). MacDonald and Leary (2012) even put this affective component at the heart of their definition of self-esteem, speaking of an affectively laden self-evaluation, which basically reflects how a person feels about him- or herself. While such an affective self-evaluation is clearly present in self-esteem as well as in self-criticism, it becomes clear from the definitions above that self-esteem refers to how a person generally or most typically feels about him- or herself, while self-criticism specifically refers to critically evaluating and attacking the self. In fact, associations between self-criticism and self-esteem range between −.44 and −.68 (Abela, Webb, Wagner, Ho, & Adams, 2006; Dunkley & Grilo, 2007), suggesting an overlap between both constructs but no perfect congruency. Possibly, self-criticism and self-esteem might even interact in predicting clinical outcomes. Abela et al. (2006) found that individuals with high levels of self-criticism and low levels of self-esteem reported greater elevations in depressive symptoms following elevations in hassles than did individuals with only one or neither of these vulnerability factors. They concluded that self-criticism is a vulnerability factor for depression but only for individuals with low self-esteem.

Altogether, the lack of a clear-cut definition of the term self-criticism poses a challenge to the study of the construct. However, the most comprehensive one might be a combination of definitions from the two research groups around Sidney J. Blatt and David M. Dunkley, who state that self-criticism involves constant and harsh self-scrutiny, overly critical evaluations of one’s own behavior, an inability to derive satisfaction from successful performance, ongoing concerns over mistakes, and negative reactions to perceived failures in terms of active self-bashing and hostility toward the self (Blatt & Luyten, 2009; Dunkley & Kyparissis, 2008; Dunkley et al., 2003).

2 Self-Criticism as Part of the Depressive Experience

The original clinical description of self-critical phenomena in depressive patients by Freud was intertwined with the description of melancholia and depression. In Freud’s view, the main difference between mourning and melancholia is the loss of self-respect, which manifests in self-accusations and self-hate (Freud, 1917). As a consequence, later clinical theories of depression evolved around the view of the self and further described how the clinical experience of self-criticism contributes to the development and shapes the clinical expression of depression (e.g., Abraham, Jacobson, and others). Building on this previous work, Sid Blatt’s further development of two pathways leading to depression has been labeled as the “double helix theory of depression” (Auerbach, 2015). Thus, although the relevance of the two dimensions relatedness and self-definition was later extended to other disorders as well, the theory originated from the description of depressed patients. Blatt proposed that one of the two forms of depression is primarily shaped by the experience of self-criticism, which further indicates the high importance of this domain for depressive disorders. As outlined above, this conceptualization is in agreement with cognitive theory and therapy, which puts negative views of the self as part of the depressive triad at the core target of the treatment (Beck, 1967). Notably, different theoretical traditions view self-criticism as integral part of depressive psychopathology.

A closer look at the criteria for depressive disorders in the main classification systems further underscores the special importance of self-criticism for depression. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) as well as the ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1993) both include feelings of worthlessness (DSM-5) and reduced self-esteem and ideas of unworthiness (both ICD-10) as part of the symptoms of a depressive episode. In comparison, feelings of dependency (which are of similar theoretical importance for the development of depression according to the theories outlined above) are not included in any of the major classification systems.

Additional support for the clinical relevance of impairments in the functional domain of self-criticism for the clinical description of depression comes from the repeated finding that self-critical subtypes of depression are especially severe and may require special care during treatment. For example, clinical literature associates self-criticism with an increased risk for serious, lethal suicide attempts. According to this line of thought, self-critical and perfectionistic patients primarily experience diminished self-worth during a depressive episode, which is accompanied by intense feelings of guilt, shame, and worthlessness (e.g., Campos et al., 2013). These intense negative inner experiences may lead to more severe overall symptoms and have a negative impact on treatment outcome (Blatt, 1995).

2.1 Regulation of Self-Esteem as an Aspect of Personality Functioning

While self-criticism in itself received considerable attention, recent developments in the dimensional assessment of personality disorders suggest that personality functioning may be closely related to the phenomenon as well. Personality functioning as an approach to assess personality disorders was reintroduced into mainstream psychiatry with the Alternative Model for the Assessment of Personality Disorders of the DSM-5 (Bender, Morey, & Skodol, 2011) as well as the personality disorders section of the ICD-11 (Tyrer et al., 2011). It provides a number of empirically derived and clinically relevant core psychological abilities with regard to the self and others that help a given individual to cope with internal as well as external demands. The DSM-5 AMPD focuses on self-worth from a general positive self-evaluation and the ability to correctly assess the self and to regulate self-esteem via reduced self-esteem with critical and biased self-view to a more pronounced vulnerability and idealization and devaluation of either the self and to fragile self-esteem with a distorted self-view, strong self-contempt, and/or self-glorification. The ICD-11 also focuses on the ability to maintain an overall positive and stable sense of self-worth and its impairment, where the self-view may be characterized by self-contempt or by grandiosity or eccentricity up to a generally poor self-worth and predominant self-defeating behaviors. DSM-5 and ICD-11 are currently in the process of being evaluated also with regard to self-worth and personality functioning (Tyrer et al., 2019; Zimmermann et al., 2019).

In addition to DSM-5 and ICD-11, there are other models that have already been related to clinical decision-making and intervention strategies for about 25 years, such as the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis System (OPD-2; Task Force OPD, 2008). Axis IV of the OPD-2 describes personality functioning as 24 facets organized in four areas of abilities related to perception, regulation, communication, and attachment, again toward to the self and others. It is conceptually and empirically related to the DSM-5 AMPD and other similar approaches (Ehrenthal & Benecke, 2019; Jauk & Ehrenthal, in press). In the OPD system, self-esteem and self-worth are present on three axes:

-

1.

It appears as a phenomenon of interpersonal patterns (Axis II) with an experience to belittle, devalue, and embarrass either with regard toward the self or another person. The OPD would take this as a rather descriptive information and try to determine the factors that drive this behavior, which can be motivational insecurities, personality function, a mixture of both, or a secondary regulatory defensive pattern in the service of other factors.

-

2.

It appears as part of a mostly nonconscious motivational conflict (Axis III). Here insecurities about the value of one’s own person are compensated either by a more “passive” habitual self-presentation as a person of less worth compared to others, often related to shame, or by an “active,” enforced, yet fragile self-confidence toward others, often related to “narcissistic rage.” Importantly, the conflictual topic usually becomes relevant in specific situations related to self-esteem such as evaluations, promotions, criticism, review, and the like.

-

3.

It is related to basic psychological capacities (Axis IV). In the OPD-2, in addition to self-reflection and identity, regulation of self-esteem is seen as a key feature of personality functioning. It describes the ability to restore an adequate level of self-esteem after related challenges and is at least conceptually seen as independent from impulse control, which is partly backed by research findings that show that instabilities in self-worth and affective instability are probably not the same phenomenon (Santangelo et al. 2020). Importantly, from the perspective of the OPD, regulation of self-worth can be relatively independent from self-worth conflicts but also occurs with other motivational insecurities and is seen as a separate target for psychotherapeutic interventions. The impact of impairment of these regulatory capacities is therefore not necessarily bound to certain topics but rather shows themselves whenever the psychological system of the individual is challenged by internal or external demands (Ehrenthal & Benecke, 2019; Ehrenthal & Grande, 2014).

Relevant for the understanding of self-criticism are therefore at least three perspectives. Firstly, all of the abovementioned models of personality functioning incorporate psychological capabilities related to self-esteem and regulation of self-worth. In other words, the phenomenon of self-criticism can be observed in interpersonal patterns toward the self and others, which are either driven by motives and motivational conflicts or formed by specific deficits of personality functioning. Secondly, the specific form and impact of self-criticism on other variables may be shaped by levels of personality functioning. If especially capacities of the self, such as self-perception and self-regulation, but also self-soothing abilities are not available, the handling of self-criticism is much more difficult than with relatively intact psychological tools. In other words, self-criticism in an individual with high levels of personality functioning looks differently from and has usually less detrimental consequences than self-criticism in individuals with generally low levels of personality functioning.

2.2 Empirical Research on the Overlap Between Self-Criticism, Depression, and Personality Functioning

Empirical research shows that self-criticism overlaps both with depression severity (i.e., depression symptoms) and with personality functioning. Typical empirical studies on the overlap report on the covariance of questionnaires, which are answered at the same time by patients and/or participants. Regarding the correlation between self-criticism and depression severity, numerous studies have been published that demonstrate a positive correlation between the two constructs. Two studies may serve as illustrative examples: Luyten et al. (2007) investigated four samples (patients with major depressive disorder, mixed psychiatry inpatients, university students, and a sample of nonclinical participants from the community) and found a consistent, positive, moderate to high association between depressive symptoms (measured with three different depression scales) and self-criticism (measured with the DEQ) in all four samples. Dinger et al. (2015) reported a similar pattern of correlations for two depressed samples (inpatients from Germany and psychotherapy outpatients in the United States) and further showed that the moderate correlation between the BDI-II and the DEQ was mainly driven by the high correlation with the BDI cognitive subscale. This finding drew attention to the significant overlap of item content in cognitively oriented depression scales with the DEQ, which aims to assess more stable dimension of experience. Thus, it is not entirely clear if the observed associations originate from particularly severe depression symptoms of self-critical individuals or if self-critical attitudes receive particularly high attention in cognitively oriented measures such as the BDI, which might inflate the observed association. Of note, Dinger et al. (2015) reported significantly lower associations between self-reported self-criticism and observer ratings of depression severity (Hamilton Scale).

Studies on the overlap between personality functioning and depression severity also report positive associations between the two constructs. For example, de la Parra, Dagnino, Valdés, and Krause (2017) found a high correlation of self-criticism (DEQ) and personality functioning (OPD-SQ total score) in a combined sample of Chilean outpatient’s and university students. Similarly, Dagnino et al. (2018) report a moderate to high correlation between OPD-SQ and the self-criticism scale of the DEQ in a sample of Chilean psychotherapy outpatients. In addition to the conceptual overlap between self-criticism and the capacity for self-regulation of the OPD structure axis, the empirical studies showed specific impairments in self-critical individuals. More specifically, self-criticism is associated with pronounced difficulties in the capacities to regulate object relationships and to attach to internal objects (Dagnino et al., 2018; de la Parra et al., 2017; Schauenburg & Dinger, 2018).

The empirical findings support the theoretical and clinical perspective that self-criticism is a relevant aspect of the depressive experience as well as an integral aspect of personality dysfunction. As further complication, measures of symptoms (e.g., depression) typically correlate in a low to moderate range with measures of personality dysfunction (Ehrenthal et al., 2012). Thus, a comprehensive analysis of all three constructs is in order to analyze their respective degree of overlap and distinct characteristics. To do so, the study by Schauenburg and Dinger recruited 80 inpatients with a major depressive disorder in a German psychosomatic university hospital. Of these, 44 patients were diagnosed with a comorbid borderline personality disorder (see Dinger et al. in press for further details). At the beginning of their inpatient treatment, patients responded to the BDI-II for depression severity, the OPD-SQ for personality functioning, and the DEQ for self-criticism. The findings showed that each variable overlaps uniquely with the other two, and there is additional shared variance between the three scales. However, more than half of the variance of each instrument is not shared with the other two constructs, which indicates that the separate assessment of the three variables is justified and provides unique information (see Fig. 7.1).

3 Self-Criticism as Predictor of Therapy Outcome

As a consequence of the strong link between self-criticism and depression (Blatt, Quinlan, Chevron, McDonald, & Zuroff, 1982; Carver & Ganellan, 1983; Cox, McWilliams, Enns, & Clara, 2004; Mongrain & Leather, 2006; Zuroff, Santor, & Mongrain, 2005), the construct and its role with regard to psychotherapy outcome gained increasing attention since the mid-1990s. One of the first studies investigating the predictive value of self-criticism for therapy outcome was the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (TDCRP, Blatt et al., 1995). The TDCRP was a multisite coordinated study that compared the effectiveness of three forms of treatment for outpatients with major depression – interpersonal therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacotherapy plus clinical management – and a placebo control plus clinical management. Results indicated that self-critical individuals experienced poorer outcomes across all four treatment conditions. Specifically, increased pretreatment levels of self-criticism, as measured by the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (Weissman & Beck, 1978), significantly interfered with treatment outcome at termination, as measured by posttreatment depression severity scores.

In another frequently cited study, depressed outpatients were randomly assigned to receive either interpersonal therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or pharmacotherapy with clinical management (Marshall, Zuroff, McBride, & Bagby, 2008). Higher pretreatment levels of self-criticism, as measured with the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (Blatt et al., 1976), predicted higher posttreatment depression levels among individuals treated with interpersonal therapy. In other words, self-criticism was also associated with poorer response to treatment but only for individuals in interpersonal therapy. The authors further found a trend toward self-criticism, predicting better response to pharmacotherapy. In a similar vein, Rector, Bagby, Segal, Joffe, and Levitt (2000) found that highly self-critical patients were more likely to have poor response to treatment. However, this was only the case for individuals treated with cognitive therapy and not for those treated with pharmacotherapy.

Overall, this selection of studies suggests a detrimental effect of self-criticism on treatment outcome, albeit differential effects for different treatment modalities seem to be present. Marshall et al. (2008) attributed these diverging findings to differences in study settings and instruments for self-criticism used. Another explanation might be that treatment methods in fact differently affect the relationship between self-criticism and therapy outcome. In line with this, Blatt and colleagues argue that self-critical patients are more responsive to long-term, intensive, insight-oriented treatments (Blatt & Zuroff, 2005). This assumption is based on the results from the TDCRP that showed self-critical individuals doing less well in brief outpatient treatment as well as the finding that the therapeutic progress among patients with high levels of self-criticism was disrupted in the latter half of the treatment process, possibly due to their anticipation of the forced termination after the 16th treatment session (Blatt et al., 2010). Further support comes from investigations that found self-critical patients showing significantly greater positive changes in open-ended psychoanalysis (Blatt, 1992; Blatt & Ford, 1994).

3.1 Meta-Analysis on Self-Criticism and Therapy Outcome

In order to permit a well-founded conclusion about self-criticism as a predictor of therapy outcome, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis on the relationship between pretreatment self-criticism and various forms of psychotherapy outcome (Löw, Schauenburg, & Dinger, 2020). The main advantage of this approach is that we do not further have to rely on findings from single studies but that conclusions can be drawn from a quantitative synthesis of relevant findings across a variety of different studies. Thus, the main goal of our meta-analysis was to estimate the magnitude and direction of the overall correlation between self-criticism and therapy outcome, summarizing what researchers have found out about this association up until today. Our definition of self-criticism corresponds with the conceptualizations of the construct by Blatt and Dunkley (see Blatt & Luyten, 2009; Dunkley & Kyparissis, 2008; Dunkley et al., 2003). Since we view self-criticism in terms of a cognitive-affective mental structure, which forms in early child-caregiver dyads and which further differentiates and changes within relationship experiences later in life (see e.g., Blatt, 1974; Blatt & Behrends, 1987), also including the therapeutic relationship, we were particularly interested in treatment outcomes following psychotherapeutic interventions. However, we considered a broad range of therapy outcomes, including primary symptom-related outcomes as well as secondary outcomes such as quality of life, interpersonal and psychological functioning, and psychological stress reactivity. We further included only studies with a longitudinal design, where self-criticism was assessed previous to or in the beginning of treatment and outcome was assessed after treatment.

Based on a systematic literature search and a set of strict inclusion criteria, we could identify 52 longitudinal studies (59 independent effect sizes), which involved 3610 patients. The overall association between pretreatment self-criticism and psychotherapy outcome across all studies was r = −.21, suggesting that the higher the level of self-criticism in the beginning of treatment, the poorer the psychotherapeutic outcome. The magnitude of this relationship can be evaluated as small to moderate (Cohen, 1992). A low degree of variability in study outcomes further suggested high comparability of single studies. Thus, on a meta-analytic level, it could be confirmed that self-criticism predicts poor therapy outcome across different treatment modalities, study designs, mental health issues, and outcome measures. However, the association between self-criticism and outcomes varied by type of mental health problem, indicating stronger associations for certain disorders (e.g., eating disorders). The type of treatment also moderated the association, showing the largest negative association between self-criticism and treatment outcome for interpersonal therapies, closely followed by other therapies, which mostly consisted of psychodynamic and emotion-focused therapies, and the lowest negative association for cognitive-behavioral therapies. At first sight, the latter finding challenges the assumption that self-critical patients respond better to psychoanalytic long-term treatment (Blatt & Zuroff, 2005). However, just a very small proportion of primary studies actually included intensive long-term treatments, so the question of which treatment duration fits self-critical patients best cannot be answered yet.

Although the meta-analysis established self-criticism as a small to moderately strong, robust predictor of therapy outcome, based on the correlational nature of primary data, we cannot assume that pretreatment self-criticism causes poor treatment response. The exclusive inclusion of longitudinal studies at least added a temporal order, but as described above third variables could still affect the association. Moreover, a handful of studies suggest that we should not only rely on pretreatment self-criticism but also on how self-criticism changes over the course of treatment and how this affects outcome. For example, Rector et al. (2000) found that, while high pretreatment self-criticism was associated with less well response to cognitive psychotherapy, the degree to which self-criticism was successfully reduced in treatment was shown to be the best predictor of outcome. Similarly, the reduction of self-criticism within a psychodynamic therapy was linked with the rate of decrease in symptomatic distress over time (Lowyck, Luyten, Vermote, Verhaest, & Vansteelandt, 2016). However, there are also studies that did not find an association between change in self-criticism over time and therapy outcome (Chui, Zilcha-Mano, Dinger, Barrett, & Barber, 2016; O’Connor, Lavoie, Desaulniers, & Audet, 2018; see systematic review of relevant studies in Löw et al., 2020). In order to better understand the potentially causal impact of self-criticism on treatment outcome and the reciprocal relationships between self-criticism and outcomes over the course of therapy, future research should use prospective designs with multiple measurement points, also taking into account further process and confounding variables. However, the meta-analysis presented here provides a significant contribution to the role of self-criticism in predicting the outcome of psychotherapy.

3.2 Self-Criticism and the Therapeutic Process

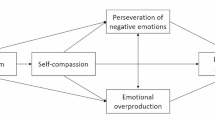

One possible explanation for the relationship between self-criticism and poor psychotherapy outcome can be withdrawn from Blatt’s two-polarities model of personality and his conceptualization of self-criticism, which state that an exaggerated preoccupation with issues of self-definition, self-worth, and self-criticism goes at the expense of learning how to build intimate and mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships (Blatt, 1974, 2006). Such deficits in interpersonal relatedness are reflected in too distant, cold, cynical, and even overtly hostile interpersonal behaviors of self-critical individuals as well as in a lack of self-disclosure in intimate relationships (Dinger et al., 2015; Dunkley & Kyparissis, 2008; Mongrain, Lubbers, & Struthers, 2004; Zuroff & Duncan, 1999; Zuroff & Fitzpatrick, 1995). Translating these findings into the therapeutic situation, analyses based on the TDCRP data showed that pretreatment self-criticism interfered with patients’ participation in the therapeutic alliance (Zuroff et al., 2000). Furthermore, the disruptions in the therapeutic alliance as a consequence of higher levels of self-criticism significantly interfered with therapeutic outcome (Shahar, Blatt, Zuroff, Krupnick, & Sotsky, 2004). The authors did not only identify self-critical patient’s difficulties in relating constructively to their therapist but also their problems with establishing and maintaining satisfying social relationships outside of treatment. Specifically, Shahar et al. (2004) found that pretreatment self-criticism predicted a less positive social network over the course of therapy, which in turn predicted less reduction of symptoms at termination. On the whole, these results suggest that relationship difficulties may mediate the association between self-criticism and psychotherapy outcomes.

In addition to the relationship difficulties that generally go along with high levels of self-criticism, the problem might aggravate for those individuals with additional low personality dysfunction. As specified above, personality functioning overlaps with self-criticism, which appears to be specifically related to the capacities to regulate relationships and to attach to internal objects (Dagnino et al., 2018; de la Parra et al., 2017; Schauenburg & Dinger, 2018). This pattern of personality dysfunctions again reflects self-critical individuals’ deficits in the interpersonal realm and even further highlights the profound scars within personality structure as a consequence of an emphasis on the developmental line of self-definition. It might help to clarify why it is so challenging to build and maintain positive alliances with self-critical patients. The difficulties in the domain of attachment (e.g., the capacity to enter a relationship with trust) and for relationship regulation (e.g., the capacity to hold back on devaluating, cynical comments) can explain why self-critical patients generally tend to behave in a cold or even cynical manner toward others (e.g., Dinger et al., 2015). This is likely to apply to the therapeutic relationship as well, where self-critical patients may be challenged by the necessity to open up toward the therapist and allow a certain degree of closeness.

We argue that in addition to the common variance between self-criticism and personality functioning, the unique variance of personality functioning appears to be important. More specifically, personality dysfunction in general may be a moderator of the association between self-criticism and alliance, with more problems arising for patients with severe personality dysfunction. Clinical and empirical evidence show that patients with severe personality dysfunction, e.g., those with borderline personality disorder, have profound difficulties to engage in a positive and helpful working alliance (e.g., Kivity et al. 2020; Levy et al., 2010; Levy et al. 2017). Thus, we argue that while self-criticism may always be a challenge for the establishment of a positive therapeutic relationship (i.e., regardless of the degree of personality dysfunction), the lack of capacities to deal with interpersonal challenge (e.g., to be able to self-reflect on these difficulties or to be able to communicate the associated emotions) will lead to even greater problems for self-critical individuals with lower levels of personality dysfunction in psychotherapy.

4 Clinical Implications

As outlined above, patient self-criticism is an influential and challenging variable in the psychotherapeutic treatment of depression, especially for the development of a secure and trusting relationship. One can further assume that patient agency, i.e., the experience of oneself as positively influential in the therapeutic process, may be hindered in self-critical individuals (Huber, Born, et al., 2019; Huber, Nikendei, et al., 2019). The first consequence that arises from this assumption is a focus on assessment. Clinicians need to know about their patients’ harsh and ungracious view of the self in order to tailor their relationship offer and therapeutic strategy toward this issue. As specified above, there are several self-report instruments that can be used either as screening tools (e.g., DEQ short forms with only 12 items, Krieger et al., 2014) or as more detailed measures to differentiate between adaptive and maladaptive forms of self-criticism (e.g., the FSCRS, Gilbert et al., 2004). Ideally, standardized self-reports are complemented by therapists’ individual assessment of the self-image, which should be part of regular intake interviews. Particularly informative are patients’ responses to therapists’ request to describe themselves. In addition, typical relationship difficulties (detached, cold, or critical interpersonal behavior) are likely to occur in the therapeutic relationship with highly self-critical patients, so a monitoring of the interpersonal “messages” toward the therapist as well as patients’ tendency to belittle or bash him- or herself during therapy needs to be noticed, taken seriously, and examined in more detail.

If self-criticism has been established as a relevant aspect of the current or chronic clinical problem of the patient, the next step should be directed toward a deepened understanding of possible sources of or risk factors for this issue (see 7.2.1 Regulation of Self-Esteem as an Aspect of Personality Functioning). In line with the OPD-2, the distinction between directly related motivational conflicts or secondary coping strategies for other motivational conflicts, on the one hand, and self-criticism as an epiphenomenon of low personality functioning, on the other hand, is crucial for tailoring the therapeutic approach (Task Force OPD, 2008). In the first case of more “neurotic levels” of good to moderately impaired personality functioning, a self-critical patient may benefit from an attentive and curious therapist, who remains alert to relationship difficulties and connects those with the phenomenon of profound self-criticism. In psychodynamic therapies, these patients are typically treated with longer-term therapy, which aims to change the negative inner representation of the self. Importantly, patients with higher levels of personality functioning can be expected to take responsibility for the therapeutic process. This means that, although the therapist nevertheless needs to display a high degree of sensitivity to the patient’s experience of their relationship and the therapy in general, patients can be expected to regulate the view of her- or himself as well as associated emotions in a tolerable corridor. However, it is important to monitor own impulses and motives toward progress, as one of the challenges is to avoid reinforcing self-critical tendencies by identifying with the patient’s wish to be a “perfect client.” In other words, therapists usually should try to slow down, be mindful about subtle interpersonal signals of insecurity as well as trust, and even consider evaluating tendencies of “imperfection” such as temporarily coming unprepared into sessions, as possible markers of progress.

On the contrary, self-critical patients with lower levels of personality functioning are likely to need more active co-regulation of their inner states, as their capacities to tolerate negative affects, to self-reflect, and to self-soothe will be impaired. Thus, therapists need to collaboratively anticipate with their clients at which points harsh self-scrutiny is likely to appear and explicitly address and try to improve the impaired related structural abilities. Generally, a parental therapeutic stance is helpful, which implies more activity and presence of the therapist to limit regressive phenomena and associated anxiety and to foster interpersonal learning (Dahl et al., 2014; Ehrenthal & Dinger, 2018; Rudolf, 2020).

The meta-analysis and review by Löw et al. (2020) did not indicate that a specific form of treatment was more effective than another for self-critical patients. However, several third-wave CBT treatments specifically aim to increase self-compassion and mindfulness as a buffer against maladaptive, self-critical perfectionism (e.g., acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, compassion-focused therapy). These treatments are effective in increasing self-compassion but not generally more effective than other bona fide therapies (Wilson et al., 2019). Future research will show if these specific treatments are differentially more effective for self-critical patients. On the other hand, approaches with less RCT-based evidence that draw on general strategies for dealing with self-criticism or build intervention strategies that target related areas of personality functioning, for example, psychodynamic treatments, should be put to empirical tests to establish a more competitive evidence based that allows for a better comparison. However, given the variety of phenomena usually associated with the topic, most research is needed on the integration of core principles for reducing self-criticism into established therapy programs. This would also fit in with current ideas of individualized treatment planning along the lines of cross-diagnostic, specific functional impairments. Thus, we would like to end this chapter with a call for further research on helpful therapeutic stances, specific interventions, treatment modules, or other psychotherapy components that prove to be helpful for the severe distress and the challenging relationship difficulties of self-critical individuals.

References

Abela, J. R. Z., Webb, C. A., Wagner, C., Ho, M.-H. R., & Adams, P. (2006). The role of self-criticism, dependency, and hassles in the course of depressive illness: A multiwave longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(3), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205280911

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Publisher.

Auerbach, J. (2015). Sidney Blatt’s contributions to personality assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1107728

Baumeister, R. F. (1993). Self-esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York, NY: Hoeber.

Beck, A. T. (1983). Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In P. J. Clayton & J. E. Barrett (Eds.), Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches (pp. 265–290). New York, NY: Raven.

Beck, A. T. (1996). Beyond belief: A theory of modes, personality, and psychopathology. In P. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of cognitive therapy (pp. 1–25). New York, NY: Guilford.

Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (2009). Depression: Causes and treatment (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford.

Bender, D. S., Morey, L. C., & Skodol, A. E. (2011). Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM-5, part I: A review of theory and methods. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(4), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.583808

Blaney, P. H., & Kutcher, G. S. (1991). Measures of depressive dimensions: Are they interchangeable? Journal of Personality Assessment, 56, 502–512.

Blatt, S. J. (1974). Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 29, 107–157.

Blatt, S. J. (1992). The differential effect of psychotherapy and psychoanalysis with anaclitic and introjective patients: The Menninger psychotherapy research project revisited. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 40(3), 691–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306519204000303

Blatt, S. J. (1995). The destructiveness of perfectionism: Implications for the treatment of depression. American Psychologist, 50(12), 1003–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.12.1003

Blatt, S. J. (1998). Contributions of psychoanalysis to the understanding and treatment of depression. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 46, 723–752.

Blatt, S. J. (2006). A fundamental polarity in psychoanalysis: Implications for personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 26(4), 494–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690701310581

Blatt, S. J. (2008). Polarities of experiences: Relatedness and self-definition in personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Blatt, S. J., & Behrends, R. S. (1987). Internalization, separation-individuation, and the nature of therapeutic action. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 68(2), 279–297.

Blatt, S. J., D’Afflitti, J. P., & Quinlan, D. M. (1976). Experiences of depression in normal young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85(4), 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.85.4.383

Blatt, S. J., & Ford, R. Q. (1994). Therapeutic change: An object relations perspective. New York, NY: Plenum.

Blatt, S. J., & Lerner, H. D. (1983). The psychological assessment of object representation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 47(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4701_2

Blatt, S. J., & Luyten, P. (2009). A structural-developmental psychodynamic approach to psychopathology: Two polarities of experience across the life span. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 793–814. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000431

Blatt, S. J., Quinlan, D. M., Chevron, E. S., McDonald, C., & Zuroff, D. (1982). Dependency and self-criticism: Psychological dimensions of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.50

Blatt, S. J., Quinlan, D. M., Pilkonis, P. A., & Shea, M. T. (1995). Impact of perfectionism and need for approval on the brief treatment of depression: The National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program revisited. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(1), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.1.125

Blatt, S. J., Shahar, G., & Zuroff, D. C. (2001). Anaclitic (sociotropic) and introjective (autonomous) dimensions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 449–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.449

Blatt, S. J., & Zuroff, D. C. (1992). Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: Two prototypes for depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 12(5), 527–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(92)90070-O

Blatt, S. J., & Zuroff, D. C. (2005). Empirical evaluation of the assumptions in identifying evidence based treatments in mental health. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(4), 459–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.001

Blatt, S. J., Zuroff, D. C., Hawley, L. L., & Auerbach, J. S. (2010). Predictors of sustained therapeutic change. Psychotherapy Research, 20(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300903121080

Campos, R. C., Besser, A., & Blatt, S. J. (2013). Recollections of parental rejection, self-criticism and depression in suicidality. Archives of Suicide Research, 17(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.748416

Carver, C. S., & Ganellan, R. (1983). Depression and components of self-punitiveness: High standards, self-criticism, and overgeneralization. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92, 330–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.92.3.330

Chui, H., Zilcha-Mano, S., Dinger, U., Barrett, M. S., & Barber, J. P. (2016). Dependency and self-criticism in treatments for depression. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(4), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000142

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Cox, B. J., McWilliams, L. A., Enns, M. W., & Clara, I. P. (2004). Broad and specific personality dimensions associated with major depression in a nationally representative sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 45, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.03.002

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2012). Contingencies of self-worth. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 309–326). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Dagnino, P., Valdés, C., de-la-Fuente, I., Harismendy, M. d. l. Á., Gallardo, A. M., Gómez-Barris, E., & de-la-Parra, G. (2018). Impacto de la Personalidad y el Estilo Depresivo en los Resultados Psicoterapéuticos de Pacientes con Depresión [The impact of personality and depressive style on the psychotherapeutic outcomes of depressed patients]. Psykhe: Revista de la Escuela de Psicología, 27(2), 1–15.

Dahl, H.-S. J., Røssberg, J. I., Crits-Christoph, P., Gabbard, G. O., Hersoug, A. G., Perry, J. C., … Høglend, P. A. (2014). Long-term effects of analysis of the patient–therapist relationship in the context of patients’ personality pathology and therapists’ parental feelings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(3), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036410

de la Parra, G., Dagnino, P., Valdés, C., & Krause, M. (2017). Beyond self-criticism and dependency: Structural functioning of depressive patients and its treatment. Research in Psychotherapy, 20, 236. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2017.236

Dinger, U., Barrett, M. S., Zimmermann, J., Schauenburg, H., Wright, A. G., Renner, F., … Barber, J. P. (2015). Interpersonal problems, dependency, and self-criticism in major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22120

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Robins, R. W. (2011). Self- esteem: Enduring issues and controversies. In T. Chamorro-Premuzic, S. von Stumm, & A. Furnham (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences (pp. 718–746). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Dunkley, D. M., & Blankstein, K. R. (2000). Self-critical perfectionism, coping, hassles, and current distress: A structural equation modeling approach. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 713.

Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Masheb, R. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2006). Personal standards and evaluative concerns dimensions of “clinical” perfectionism: A reply to Shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and Hewitt et al. (2003). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.004

Dunkley, D. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2007). Self-criticism, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and over-evaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(1), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.017

Dunkley, D. M., & Kyparissis, A. (2008). What is DAS self-critical perfectionism really measuring? Relations with the five-factor model of personality and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1295–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.11.022

Dunkley, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Blankstein, K. R. (2003). Self-critical perfectionism and daily affect: Dispositional and situational influences on stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.234

Dunkley, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Blankstein, K. R. (2006). Specific perfectionism components versus self-criticism in predicting maladjustment. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(4), 665–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.08.008

Ehrenthal, J. C., Dinger, U., Horsch, L., Komo-Lang, M., Klinkerfuß, M., Grande, T., et al. (2012). Der OPD-strukturfragebogen (OPD-SF): erste ergebnisse zu reliabilität und validität. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 62, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1295481.

Ehrenthal, J. C. & Grande, T. (2014). Fokusorientierte Beziehungsgestaltung in der Psychotherapie von Persönlichkeitsstörungen – ein integratives Modell. PiD - Psychotherapie im Dialog, 3, 80–85.

Ehrenthal, J. C., & Dinger, U. (2018). Strukturdiagnostik in der Praxis – von der Indikation zur Therapieplanung. Ärztliche Psychotherapie, 14, 32–40.

Ehrenthal, J. C. & Benecke, C. (2019). Tailored treatment planning for individuals with personality disorders: The OPD approach. In: U. Kramer (Ed.). Case Formulation for Personality Disorders: Tailoring Psychotherapy to the Individual Client. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier, pp. 291–314.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Oliver, J. M., & Macdonald, S. (2002). Perfectionism in children and their parents: A developmental analysis. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 89–132). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia (Standard edition 14) (pp. 243–248). New York, NY: Vintage.

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N. V., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504772812959

Hewitt, J. P. (2002). The social construction of self-esteem. In C. R. Snyder & S. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 135–147). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Huber, J., Born, A.-K., Claaß, C., Ehrenthal, J. C., Nikendei, C., Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2019). Therapeutic Agency, In-Session Behavior and Patient-Therapist Interaction. Journal of Clincial Psychology, 75, 66–78.

Huber, J., Nikendei, C., Ehrenthal, J. C., Schauenburg, H., Dinger, U. (2019). Therapeutic Agency Inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 919–934.

Irons, C., Gilbert, P., Baldwin, M. W., Baccus, J., & Palmer, M. (2006). Parental recall, attachment relating and self-attacking/self-reassurance: Their relationship with depression. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 12, 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X68230

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. New York, NY: Holt.

Jauk, I., & Ehrenthal, J. C. (in press). Self-reported levels of personality functioning from the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis (OPD) system and emotional intelligence likely assess the same latent construct. Journal of Personality Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2020.17750891

Katz, J., & Nelson, R. A. (2007). Family experiences and self-criticism in college students: Testing a model of family stress, past unfairness, and self-esteem. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(5), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180601057630

Kernis, M. H. (2006). Self-esteem issues and answers: A sourcebook of current perspectives. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Kernis, M. H., & Waschull, S. B. (1995). The interactive roles of stability and level of self-esteem: Research and theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 27, pp. 93–141). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Kivity, Y., Levy, K. N., Kolly, S., Kramer, U. (2020). The therapeutic alliance over 10 sessions of therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: Agreement and congruence analysis and relation to outcome. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34(1), 1–21, 2020.

Krieger, T., Zimmermann, J., Beutel, M. B., Wiltink, J., Schauenburg, H., & grosse Holtforth, M. (2014). Ein Vergleich verschiedener Kurzversionen des Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ) zur Erhebung von Selbstkritik und Abhängigkeit. Diagnostica, 60(3), 126–139.

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1–62). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Levy, K. N., Beeney, J. E., Wasserman, R. H., & Clarkin, J. F. (2010). Conflict begets conflict: Executive control, mental state vacillations, and the therapeutic alliance in treatment of borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 20, 413–422.

Levy, K. N., Scala, J. W., & Ellison, W. D. (2017). The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A metaanalysis. Manuscript in preparation.

Löw, C. A., Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2020). Self-criticism and psychotherapy outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 75, 101808.

Lowyck, B., Luyten, P., Vermote, R., Verhaest, Y., & Vansteelandt, K. (2016). Self-critical perfectionism, dependency, and symptomatic distress in patients with personality disorder during hospitalization-based psychodynamic treatment: A parallel process growth modeling approach. Personality Disorders, Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(3), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000189

Luyten, P., Sabbe, B., Blatt, S. J., Meganck, S., Jansen, B., De Grave, C., … Corveleyn, J. (2007). Dependency and self-criticism: Relationship with major depressive disorder, severity of depression, and clinical presentation. Depression and Anxiety, 24(8), 586–596. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20272

MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2012). Individual differences in self-esteem. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 354–377). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Marshall, M. B., Zuroff, D. C., McBride, C., & Bagby, R. M. (2008). Self-criticism predicts differential response to treatment for major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20438

Mongrain, M., & Leather, F. (2006). Immature dependence and self-criticism predict the recurrence of major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(6), 705–713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20263

Mongrain, M., Lubbers, R., & Struthers, W. (2004). The power of love: Mediation of rejection in roommate relationships of dependents and self-critics. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(1), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203258861

O’Connor, K., Lavoie, M., Desaulniers, B., & Audet, J. S. (2018). Cognitive psychophysiological treatment of bodily-focused repetitive behaviors in adults: An open trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22501

Rector, N. A., Bagby, R. M., Segal, Z. V., Joffe, R. T., & Levitt, A. (2000). Self-criticism and dependency in depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(5), 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005566112869

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rude, S. S., & Burnham, B. L. (1993). Do interpersonal and achievement vulnerabilities interact with congruent events to predict depression? Comparison of the DEQ, SAS, DAS, and combined scales. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 17, 531–548.

Rudolf, G. (2020). Structure-oriented psychotherapy [Strukturbezogene Psychotherapie]. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer.

Santangelo, P. S., Kockler, T. D., Zeitler, M. L.., Knies, R., Kleindienst, N., Bohus, M., & Ebner-Priemer, U. (2020). Self-esteem instability and affective instability in everyday life after remission from borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder amd Emotion Dysregulation 7, 25(2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00140-8

Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2018). How does self-criticism overlap with personality functioning and depression severity? Paper presented at the Society for Psychotherapy Research (SPR), 49th International Annual Meeting, Amsterdam.

Sedikides, C., & Gress, A. P. (2003). Portraits of the self. In M. A. Hogg & J. Cooper (Eds.), Sage handbook of social psychology (pp. 110–138). London, UK: Sage.

Shahar, G. (2015). Erosion: The psychopathology of self-criticism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Shahar, G., Blatt, S. J., & Zuroff, D. C. (2007). Satisfaction with social relations buffers the adverse effect of (mid-level) self-critical perfectionism in brief treatment for depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(5), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.5.540

Shahar, G., Blatt, S. J., Zuroff, D. C., Krupnick, J. L., & Sotsky, S. M. (2004). Perfectionism impedes social relations and response to brief treatment for depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.2.140.31017

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_2

Swann, W. B., & Bosson, J. K. (2010). Self and identity. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, 5th ed., pp. 589–628). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Task Force OPD. (2008). Operationalized psychodynamic diagnosis OPD-2. Göttingen, Germany/Toronto, ON: Hogrefe.

Thompson, R., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). The levels of self-criticism scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00106-5

Tyrer, P., Crawford, M., Mulder, R., Blashfield, R., Farnam, A., Fossati, A., Kim, Y., Koldobsky, N., Lecic-Tosevski, D., Ndetei, D., Swales, M., Clark, L. A., & Reed, G. M. (2011). The rationale for the reclassification of personality disorder in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Personality and Mental Health, 5(4), 246–259.

Tyrer, P., Mulder, R., Kim, Y.-R., & Crawford, M. J. (2019). The Development of the ICD-11 Classification of Personality Disorders: An Amalgam of Science, Pragmatism, and Politics. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15(1), 481–502.

Weissman, A. N., & Beck, A. T. (1978). Development and validation of the dysfunctional attitudes scale. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Convention, Toronto, Canada.

Whelton, W. J., & Greenberg, L. S. (2005). Emotion in self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1583–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.024

Wilson, A. C., Mackintosh, K., Power, K., & Chan, S. W. Y. (2019). Effectiveness of Self-Compassion Related Therapies: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10, 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1037-6

World Health Organization(WHO). (1993). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Zimmermann, J., Kerber, A., Rek, K., Hopwood, C., & Krueger, R. (2019). A Brief but Comprehensive Review of Research on the Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, 92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1079-z

Zuroff, D. C., Blatt, S. J., Sanislow, C. A., III, Bondi, C. M., & Pilkonis, P. A. (1999). Vulnerability to depression: Reexamining state dependence and relative stability. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.108.1.76

Zuroff, D. C., Blatt, S. J., Sotsky, S. M., Krupnick, J. L., Martin, D. J., Sanislow, C. A., 3rd, & Simmens, S. (2000). Relation of therapeutic alliance and perfectionism to outcome in brief outpatient treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 114–124.

Zuroff, D. C., & Duncan, N. (1999). Self-criticism and conflict resolution in romantic couples. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 31(3), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087082

Zuroff, D. C., & Fitzpatrick, D. K. (1995). Depressive personality styles: Implications for adult attachment. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(2), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00136-G

Zuroff, D. C., Mongrain, M., & Santor, D. A. (2004). Conceptualizing and measuring personality vulnerability to depression: Comment on Coyne and Whiffen (1995). Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 489–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.489

Zuroff, D. C., Sadikaj, G., Kelly, A. C., & Leybman, M. J. (2016). Conceptualizing and measuring self-criticism as both a personality trait and a personality state. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1044604

Zuroff, D. C., Santor, D., & Mongrain, M. (2005). Dependency, self-criticism, and maladjustment. In J. S. Auerbach, K. N. Levy, & C. E. Schaffer (Eds.), Relatedness, self-definition and mental representation. Essays in honor of Sidney J. Blatt (pp. 75–90). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dinger, U., Löw, C.A., Ehrenthal, J.C. (2021). The Functional Domain of Self-Criticism. In: de la Parra, G., Dagnino, P., Behn, A. (eds) Depression and Personality Dysfunction. Depression and Personality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70699-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70699-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-70698-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-70699-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)