Abstract

In North America, models of care within care home settings are derived from institutional hospital settings resulting in decisions over daily practices being driven by efficiency and financial accountabilities. The Culture of Care project seeks to shift the culture of care in long term care homes from an institutional model, to a social, person directed model by uplifting the perspectives of the people residing in care homes; creating the space for them to shape the future of their care. Working in collaboration with health care leaders, staff, people living in long-term care and their families, design researchers engaged participatory design research methodologies in order to foster the relationships and conversations that activate latent knowledge embodied in the people living in long-term care. Negotiating differences of approach to transformation, risk aversion in a health context and developing trust around the design research process were central to facilitating change from within the health context. Over the course of two years, the Culture of Care project created a series of workshops, media, events and toolkits that were intended to scale and connect with the people living in fifty-five care homes across the greater Vancouver area and Sunshine Coast. In this case study, we discuss how participatory design activities can be scaled to create the possibility for large organizational systems change, through deep collaboration between organizational leaders, users and external designers.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Shifting from Institutionalized Patient-Centered Care, to Social, Person Directed Care

Poet, Theo E.J. Wilson, describes language as “…the first form of virtual reality… a symbolic representation of the physical world” and that “through this device, we change the physical world.” A patient-centred view of a person living in a care home positions them as a patient first—not as a person. Definitions used to describe how a person can be centered in their care when considering people living with Dementia (PLWD) have come to include such a wide array of approaches or values that it’s meaning has become clouded [1]. Seldom does the language associated with centering PLWD speak to how the person themselves can be a contribution. Person-directed care is a designed language change intended to see people, not patients living in care homes. Person-directed care looks beyond care staff; it is looking at the people living in long-term care (LTC) to activate possibilities for agency.

In a similar manner, language used in this project to refer to LTC avoid words like “facility” and other highly medicalized or institutionalized language that positions a place where people live as anything other than “Home.” Emphasizing the social is a call to encourage exchange, to connect with storytelling as a source of knowledge, and to re-center the voice of people living in LTC as a method of improving the quality of life in LTC.

The quality of care and the performance of LTC and its health care leaders can often be resolved down to a reported number to federal bodies. Empirical data can be seen as a safer, more reliable choice. However, numbers can mask or overlook the diversity of experience of the individuals that compose the data. For example, 62% of the people living in Canadian care homes are PLWD and 1 in 5 people living in LTC are prescribed antipsychotic medication, without the diagnosis of psychosis [2]. These numbers call into question the use of medication in care homes specifically in relation to PLWD and are causing national advocacy organizations to engage and question the prevalence of perusing non-pharmacological, personalized alternatives [3].

LTC Health Care Leaders at VCH had long sought new approaches to address the systemic challenges that numbers alone simply were not resolving. As Federal bodies began to recognize an increasing practice of prescribing antipsychotics in LTC, these resilient Health Care Leaders finally had the go-ahead to approach this complex issue from a new direction in their partnership with the Health Design Lab at Emily Carr University of Art + Design.

2 Partnering to Integrate Participatory Design Research Practice into Care Innovation

Health innovation is largely rooted in empirical data born out of traditional research methods. Incremental, data driven change has, to-date not facilitated the re-imaging of LTC in British Columbia as data histories offer little space innovation and transformation [4]. Workarounds to systemic problems in the delivery of care demonstrate the creativity of care staff and their commitment to deliver the best care possible despite systemic challenges. Without creating opportunities for new, holistic measures of good care that go beyond clinical need, transformation projects are forced to innovate in a system that values and evaluates using metrics that relate to past practice and struggle to understand the complexity or root of the issue at hand [5]. Operational hierarchies, for example, and task-based cultures in Canadian hospitals ensure that patients are treated as efficiently and safely as possible. Care homes however, are not the same as hospitals—they are places where people live through to the end of life, they are homes—or at least they should be. Task-based cultures, encouraged by the performance-based metrics of evaluation, can leave people in care homes feeling like they are a burden; like their life is secondary to the operations of the home. Sometimes higher-functioning people may hesitate to ask for support given the working capacity of staff and in lieu of the needs of people requiring complex care such as people living with advanced Dementia. In this way people living in care homes are triaging their needs to support care staff in performing in a way that they health system rewards.

“Quality Improvement” (QI) is the process by which most health innovation in care occurs. QI is an iterative process which takes generalizable scientific evidence, applies it to a specific context where in the impact of the change is measured, change plans are created and said plans are implemented [6]. QI offers the reliability and security in making an argument supported by research and offering confidence to leaders in making changes that can directly impact people’s health. QI systems fit well within the models of education and care associated with health practice and delivery and offer Health Care Administrators a sense of security bound in history. QI, however, is thus reliant on past data, which constrains innovation to patterns of the past—not offering space for the transformational restructuring of cultural practice [4].

Participatory design methods start with the person or peoples that are the recipient of a product or service. A participatory approach facilitates the user in creating new experience-based data through meaningful co-creative engagement. Instead of looking to past research to describe a next step or support a decision, participatory strategies move with the evolutions of human connection, offering transformational possibility in actioning emergent data [7].

Living and working in an incredibly structured environment, design methods create opportunities in LTC for more divergence of thought—opening new pathways to share and understand. While difficult to test and offer the reassurances the QI system promises, emergent experience-based data is unquestionably valid. Next steps in large scale participatory projects are directed by the synthesis of volumes of diverse human experiences, documented through co-creative practice. The introduction of designers and designerly ways of doing into a health context offers space for person-directed care by stepping outside of linear solution focused systems and into the complexity connected to inclusion [5].

In 2018, Health Care Leaders at VCH embarked on a journey to shift the culture of care in LTC in partnership with the Health Design Lab and its team of Graduate and Undergraduate Design Research Assistants. Driven by an initial desire to reduce the prescription of antipsychotics, the integration of participatory design methods allowed Health Care Leaders to better understand the needs and perspectives of people living in care. This, the Culture of Care project, seeks to create a sustainable change in LTC, in co-designing a new culture led by people living in LTC.

3 Culture Creating Strategy

Harvard Business magazine defined strategy as “… a set of guiding principles that, when communicated and adopted in the organization, generates a desired pattern of decision making. A strategy is therefore about how people throughout the organization should make decisions and allocate resources in order to accomplish key objectives. A good strategy provides a clear roadmap, consisting of a set of guiding principles or rules, that defines the actions people in the business should take (and not take) and the things they should prioritize (and not prioritize) to achieve desired goals” [8]. Strategy has historically been a management level task of establishing direction and clarity for people in service/production positions to work collaboratively and uniformly towards.

In the Culture of Care project, strategy begins with bringing to light the rich stories, experiences and aspirations of people living in long term care. Through co-creative workshops, people in care homes were reconnected with their personal histories, current lived experiences and their desires for their future. It is the synthesis of these rich narratives and insights called to light by the people living in long term care that iteratively shape the VCH LTC strategy for culture change. The goal of this project is to have the people living within the walls of LTC create the principles, roadmaps and rules that guide the decision making that creates their world and its culture.

In creating workshops, media, communication materials and toolkits HDL researchers drew from research in the fields of placemaking, sensory engagement, storytelling, mindfulness and play in order to draw out the tacit and embodied memories and ideas from a participating group of people that live with a range of visible and invisible disabilities.

Placemaking. A sense of place comprises the ways in which people form connections with physical and social space. It is the tactile, emotional, relational and symbolic bonds that are experienced within physical space and community [9]. By focusing on the social and sensory experiences of a space it is possible to build a sustained sense of meaning connected to a location. Activities explore how people living in care would like to engage in their community and with the physical space and systemic structures of their care homes. Questions called participants to express how they felt a sense of belonging and what creates a sense of home for them.

Sensory Engagement. Employing the senses encourages rich and meaningful story telling while supporting people with invisible and visible disabilities, namely, PLWD, [10] who represent a significant portion of the LTC community. Sensory stimuli bring out latent and surface embodied information, calling forward a deeper level of knowing and often more meaningful and personalized expressions of self [11]. Creating opportunities for people in care homes to voice latent or tacit knowledge serves to validate that knowledge and can bring a sense of value and purpose to people living in care homes.

Storytelling. is a practice used across many cultures as a mode of sharing histories and passing along knowledge. Storytelling promotes communication, expression and creates an opportunity to learn about each other. Making this form of communication a normative practice in care homes builds a powerful tool for people living in homes and care teams alike to validate and cultivate the voices and choices of people living in the care homes.

Mindfulness. Creating a practice in generating awareness helps people to move beyond habitual internal dialogues. This practice can give rise to opportunities for people to reconnect with the foundational values and feelings that give rise to a meaningful existence. The goal of designed activities aimed to generate this awareness by offering sensory stimuli and working to connect these stimuli to stories and feelings; to encourage multi-sensory manners of engaging with the world that allow a person to become more comfortable with the present. Activities call a person to pay attention to and make sense of how their body reacts to various experiences and in turn how these experiences inform their preferences.

Play. The theme of playfulness was embedded throughout the event to remove the participants from the task-oriented methods of engaging with their environments as they would in an otherwise institutional setting. Play connects readily to different time periods of life, to different forms of interaction and often calls in social elements making play and access point into exploring a person’s experience [12].

4 Scaling Participation

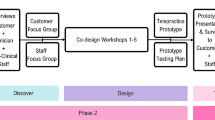

This project and partnership is currently in its third year of collaboration, working in a flexible, iterative and emergent way towards the goal of culture change. To date this partnership has included several key phases described in the sections to follow

-

1.

Developing themes

-

2.

Designing communication to scale

-

3.

Regional launch: Scaling participation

-

4.

Tool design for cultural development.

4.1 Problem Finding: Developing Themes

The Culture of Care project began in the Fall of 2018 with initial meetings and workshops between HDL designer researchers and VCH Health Care Leaders and staff to gain an initial understanding of the current culture and challenges at hand. This included a review of previous meeting minutes and initiatives through the VCH Dementia Care Team over the past couple of years, facilitation of a participatory design workshop with the Residential Practice Team, which included activities such as mapping the flows of communication and identifying barriers to culture change, as well as a workshop with Care Home Directors to identify areas of interest for change within their homes. During this preliminary phase it became clear that people living within the homes must be involved for this cultural shift to occur. Starting in January 2019, the key objective was to gain an understanding of the lived experience in care and to have people living in LTC define what ‘good care’ means to them. Working in partnership with the VCH Dementia Care Team, Design Researchers with HDL visited six care homes and talked with forty-six people, asking two key questions, ‘What experiences are important to you?’ and ‘What does good care look like to you?’. These questions were asked through participatory design workshops hosted at six care homes, following an open invitation to all care homes to participate in the project by hosting a workshop at their care home. Once a care home agreed to host a workshop, they invited the people living in the home to participate in the workshop, and their family members were also invited to participate if they desired. The workshops were co-led by design researchers and staff from the VCH Team and used image cards as prompts for dialogue around these two questions. Questions were intentionally selected to be future-oriented, to create a safe environment for people living in the home to provide input and ideas.

Thematic synthesis of thoughts, stories and feelings expressed by people living in care, were distilled into five themes through affinity mapping of detailed workshop notes collaboratively with the VCH Administrators. These initial sessions introduced these health leaders, who tend towards a more linear, task based or hierarchical approach, to analysis of qualitative data and designerly approaches to mapping complexity. This foundational basis of shared understanding of human centered, participatory research methods have built design capacity within the VCH Dementia Care Team, offering new tools and methods to reconceptualize the complex healthcare challenges of this institutionalized system.

The findings of this initial phase of research created the grounding for a culturally driven strategic change, defined by the following themes described by the people living in long term care:

Building relationships and conversations. Building strong relationships and making space for conversations that are meaningful allows people to feel at ease and find a sense of belonging within the home.

Strong relationships can support patience and empathy in helping people to get to know each other’s likes and dislikes. People said they prefer to know and have a strong relationship with their care as this can often help people feel more comfortable expressing what they need and want. Similarly, friendships can help those who feel uncomfortable asking for help.

Looking after Individual Needs and Care. Each person has a different background and a different set of needs and wants. Language, food, hobbies, fitness, and access to information are all areas that can require individual care routines.

People want care that is focused both on each individuals’ physical as well as emotional well-being. Being able to access activities that meet individual needs and help fulfill personal dreams is so important for an individual’s personal growth.

Giving Time for Flexible and Spontaneous Care. Flexibility in care gives people living in care homes a sense of freedom and independence. It lets people receive care and live in care homes on their own terms, like they would within their own homes. Because care homes operate within a strict scheduling system, including meals, sleeping and social time, impromptu actions are limited as is the staff’s ability to respond flexibly. By limiting flexible and spontaneous care, the current culture of care also limits voice and choice Staff may avoid creating opportunities to try new things, if they think a person may not be able to do it. Assumptions around ability, therefore, can also limit flexibility.

Recognizing and Supporting Ability. Assumptions about the abilities of people who live in care homes sometimes cause them to be excluded and can cause people to question their own ability.

Sometimes, in an attempt to provide care, a culture can be created that limits how people think about their own abilities—holding people back rather than encouraging their independence.

Creating a Sense of Purpose. Before living in care homes, people’s activities are generally purpose-driven: cooking for family, walking to the store to get groceries, building skills to reach personal goals. But after moving into care homes that sense of purpose is often lost, since all of a person’s basic needs are cared for. Many people are rewarded by and expressed a desire to help and support their home and community or participate in activities that offer fulfillment instead of entertainment.

People living in homes can begin to see themself as patients, rather than as individuals with free will and aspirations.

4.2 Scaling the Reach of the Voices We Heard: Communication Designed to Re-Frame the Future

Part of shifting culture is offering a new way of looking in order to create the space for seeing the world in a new light. In choosing a method to share the five core tenants of the new culture of care, the HDL Research team was especially attentive to the manner in which an aging population is spoken to, and the manner in which they are portrayed. By reconsidering, reframing and trying different methods to shift the traditional ways people living in care homes are communicated to while shifting the modes of communication received from and portrayal of people living in care homes. Researchers did this by developing evocative visual systems that were carried through within all forms of communication sharing. Content created would be shared with all 55 long term care homes by VCH staff and needed to service the unique needs and audiences at each home.

The HDL team elected to create an animated video, narrated by people living in care homes, with a companion PowerPoint slide deck that would allow facilitators from VCH to tailor content and questions to the unique needs of their home, allowing for continued conversation (Fig. 1).

Vibrant colours and collage inspired imagery painted people in care in a new light; inspired by the vibrant clothing and spirit of the video’s narrators, each slide and storyboard were created to emphasize the wealth of personal narrative and diverse identities within the homes. In depicting the stories, the team elected not to use people’s faces but rather used birds and people’s hands as symbols of new beginnings, global connections, and a collective diversity while maintaining a unique identity. Shapes were used to describe communication and language difference offering a more inclusive way of describing difference. Videos included text captions in both English and Cantonese for those hard of hearing and were posted to YouTube in hopes that translation services could support those with different language needs.

In order to test and prototyping ways to express themes, the HDL team set up Pop-Up recording stations at select care homes and recruited people living in homes to bring the previously collected quotes to life, in voice acting their stories for use in the subsequent animations. Arriving into the care home with a laptop and a microphone proved that flexible and spontaneous activity was within the staff’s capacity. Participants while often feeling initially that they may not be able to read or recite effectively, ultimately felt a sense of accomplishment; of their voice having meaning; that their ability was being supported. The creation of the videos, thus, served as a proof of concept, prototyping the effects of implementing the themes.

The inclusion of VCH care staff and Dementia Care team throughout the process of production of the video’s companion slide deck offered a nuanced language which could engage both the care staff and people allowing for a multi-dimensional approach to how the five themes might be workshopped. Collaborating in this way positioned the materials as flexible and adaptable, allowing staff to consider the relevancy and specific messaging that could best support their home; to see themselves within the content. Creating opportunities for all those in contact with the content to be a contributor that hierarchies and ingrained manners of working have space to shift.

4.3 Regional Strategy Launch “Come Alive”: Create the Space for Health Care Workers to Lead Co-creation Activities

In October of 2019, VCH LTC, in partnership with HDL, launched the Culture of Care project to the health region in a 100 + person event called “Come Alive”, which was attended by representatives from sixteen care homes including Care Staff, Health Care Leaders, Licencing Officers, and family of people living in care. The aim of this event was to re-centre the voice of people living in care homes as well as to familiarize a large audience of care home representatives with co-creative practices for visioning cultural change and relationship development within their care homes. While the design team stressed the importance of the active involvement of people living in homes at this event, logistical and administrative boundaries that still exist within LTC prevented the VCH team from being able to coordinate their inclusion for this specific workshop. It is our intention to continue to work towards finding ways for this inclusion to be possible with future events.

Sharing this role of facilitation with VCH LTC embedded participatory facilitation methods into the core competencies of Care Providers and Health Care Administrators, furthering our ability to integrate co-design methods and shift towards a more social, person directed model of care. Creating co-facilitation teams including a HDL designer and a VCH staff member for each table of 10; the co-creation session created an opportunity for participants, largely staff, to view their colleagues in a new light and see a shift in approach coming from within. Stories of care were shared while at the same time attendees were able to listen and support each other in the challenges of the current institutionalized system.

Upon entering the event attendees were given a nametag and a coloured bird which they were encouraged to decorate at a table of their choosing with a range of available materials. This craft-based activity engaged attendees’ bodies, taking them away from their phones and opening up space for dialog and creativity. A key learning from this event was that tangible, co-creative activity for those engaged in the work of health supports a richer more engaged dialog as these individual’s normative practice to multitask (Fig. 2).

After receiving the presentation, inclusive of the animated videos, attendees were led through three activities:

Reflection Activity. Table Cards, designed to reflect each theme presented in the video, provided a tangible asset for tables of 12 to consider the voices in their homes that connect with the stories shared. This activity supported the table, which had representation from multiple homes, in getting to know each other, gain comfort in sharing with each other and primed them to consider how each theme is expressed in their space.

House Activity. Moving deeper into an embodied and mindful exploration of placemaking and thematic resonance within each home; the next activity had participants explore their homes from a more sensory perspective. Prompted to select a room within the poster depicting typical spaces found within the home, participants were asked to place their bespoke bird into a room of their choosing and explore how it smelled, what the quality of light was and other sensory prompts. Going around in a circle each participant picked up a “How Might We?” Card which posed a series of questions calling the participant to reimagine the space their bird occupied. In this way the participant is encouraged to move beyond ingrained habitual thinking and to consider the lived experience. This step in the workshop built and embodied sense empathy and therefore expressed a more nuanced response to possibilities within the space beyond top-of-mind ideas.

Tree Activity. Finally, after having considered the possibility of a new experience within the walls of the home, participants were guided through a visioning process that called them to consider from a social, cultural and emotional perspective where they would like to see their home move towards with corresponding questions that pushed participants to develop blue sky type vision for what culture change could look like.

4.4 Tools Designed for Person-Directed Culture Development

In the months that followed “Come Alive”, the VCH Dementia Care team, having built confidence and proficiency at leading participatory sessions, facilitated both the presentation and select activities from the October 2019 event to all fifty-five long term care homes in order to onboard the region to the work to come.

Upon hearing the videos, many participants recognized their own voice and there were requests from people in homes to get the opportunity to share their own stories. Oftentimes, the tools developed were used in an adaptive manner in order to serve the specific needs of each care home. The message, tone and vibrancy of the videos resonated with people living in homes and in-turn Health Care Administrators and care teams saw how these messages applied to the culture that they too work within. Residents did express apprehension, however, about exactly what was going to happen and when. Some residents expressed a clear call to action; that their time was limited and that an urgency and commitment to change was important.

As the Dementia Care team shared the presentation slide deck and co-creative activities with the broader region, the HDL team set to work considering how to begin to further explore the five themes presented in a participatory manner at all fifty-five VCH long-term care homes. As a first step to shift institutional hierarchies and re-imagine the unique culture within each VCH care home, the HDL researchers considered approaches to activities that could engage staff, people and community in developing personalised visions describing possibilities for contribution to care.

An important consideration in the design of the next step of the project was how to scale participation. How, could a team of four designers co-create with an entire region? Having co-facilitated within the VCH team in the space there was a small capacity for those employed by the health region to support—however it was important that people living in homes themself become directors of their own life in ways that felt important to them. Thus, the team selected the form of a game, one that could be easily reproduced and live contextually within shared space in the homes.

“Time Traveler” Game Theory Inspired by the Life Café [13] toolkit designed by the Lab4Living, “Time Traveler” is an activity that brings people together and provides prompts and provocations for storytelling that supports the development of relationships and conversations. The game facilitates reflection upon when and how people have felt purposeful in their pasts, thus imagining what that Sense of Purpose might look like in the care home in their present. The relationships built through creating a practice of storytelling and listening serves as a means of spontaneous support in an otherwise highly structured system—it proves that care can be found in the untapped resources of the people living in care, themselves in addition to other community members. Storytelling also makes space for people to express personal histories of accomplishment, hardship, value and meaning—in sharing these stories there is space created for others to see and seek out these traits and values from the individual allowing for the care home to more organically and authentically recognize and support the abilities of people.

Finally, a goal of this activity is for people to feel more self-expressed, for their individuality, for requesting or creating the conditions that serve their holistic needs and care in sharing and creating a new and personalized narrative built off the past and re-centered into the present.

Objects used in the game were selected based on analysis into their power to surface strong feelings and memories from those who interact with them. In sourcing and understanding objects to include in Time Traveller, researchers looked for objects with an uncanniness, relationality and transitionality [14]. Consideration in object research spanned cultural association, key global events, personal transitions and rites of passage, and moved from universality to cultural specificities for the first iteration of list of objects considered for time travel. Finally, the team did a sensory survey of objects in this investigation into their evocation.

When considering the form of time travel the researchers focused on the idea of familiar ritual, awe and gift giving. The desire was to create a sense of embarking on a new journey, on learning and one sharing. Thus, having time capsules in the form of small boxes to be easily opened and revealed became central to our journey through time.

While the evocation of objects brings to the fore a richness of personal narratives and hints as to personal aspiration or value, the sense of time travel breaks game players out of a task based or linear system deeply ingrained within the lives of staff and thereby people living in homes. This disconnect from the linear borne out of play creates space for ideation within the home that may give rise to new opportunities yet unexpressed.

Co-Development with VCH LTC In a series of co-development sessions, the researchers worked within care homes across the VCH region to understand connection, interaction, relationships created between objects, and individuals.

These in-context interactions offer designers a view into health systems, caregiving and living within the walls of a care home. Imbedding design research assistants within the health space builds the capacity of this trade to better support health systems in future. While the students outside and unbiased perspectives on possibilities for culture change can create the space for new ideas—a grounded understanding of the lived experience and in person interaction with the people that live in care ground ideas in reality. Trialing the game and understanding capacity of staff supported the designers in better understanding the challenges designing for visible and invisible disability, breadth of cultural diversity and connection of the game’s intention with its participants.

The in-home sessions supported the development of a guide which could be easily administered either by a person living in care or care staff member. Co-development supported and informed the design of the game in the space of participation, and in how people in a broad range of mental and physical health might be able to participate while attuning the researchers to the rich cultural diversity that exists in LTC in the Vancouver region.

Game Design for Scalable Participation: Time Traveler The Time Traveler takes its participants on a journey back in time to recall old memories, share experience and reflect on how those experiences and sentiments can be valuable in the present. It uses iconic and tactile objects to trigger memories and concurrent emotional associations through sensory provocation.

The activity begins by unveiling a suitcase that contains tools for a journey into a person’s past. These tools include:

-

Time capsules or a series of 9 covered boxes containing evocative objects

-

Evocative objects that operate as tickets to travel and as memory triggers.

-

-

Feeling Cards to describe and support a felt description of memories

-

Postcards that act as souvenirs and qualitative data collection tools

-

Facilitation guide which operates as the conductor to time travel ensuring transportive experience and a rich exchange.

To embark on this journey to the past, the facilitator asks the participants to select an object that they are drawn to, then probes for its connection to story and to the past. The participants follow each other along into their personal histories learning about the unique narrations of each individual’s life. Participants are asked to deepen these stories by selecting a feeling card that is associated with their story and describe how this feeling is linked to their memory. The participants are then asked to carry that feeling they connected back into their present and to consider if they have the same emotional associations that surface. When do they feel the same emotion, feeling, sensation, interaction etc. in their care home? This initiates a moment of being present, connected to the past, a moment to recognize their own voice, the relationships being fostered around the table and the engagement participants have with their care home and community (Fig. 3).

Personal observations can be scribed onto postcards allowing each home to slowly build a picture of the stories, values and personal histories of the people within the home.

In March of 2020 As the team prepared to produce and deliver 55 Time Traveller toolkits at and 100 + person event that included residents from across the health region the COVID 19 Pandemic began to emerge and called all personal and tangible interaction with populations in LTC to a halt.

5 Pandemic Pivot

The COVID-19 pandemic has called for a pivot in approach in the researchers’ interactions with long term care. In efforts to keep people in homes healthy and safe strict protocols have been implemented often limiting opportunities for connection and culture development. Meanwhile, families expressed their heartfelt desire to communicate with and support their loved ones through this challenging time. With the health system focused on saving lives, and protecting staff, the HDL research team has started to engage families in co-creative virtual workshops in order to ideate possible new modes of connection. This difficult moment has presented a new opportunity to extend the culture within the home, out, and to weave family more intentionally into the culture of care within long term care.

6 Conclusion

Shifting to a person driven culture within LTC is not simple and it is not fast. LTC culture has been bound in assumptions around ability and ingrained in a rigid working culture. In collaboration with designers, LTC can gain proficiency in divergent thinking and comfort in emergent change. Designers can facilitate this transformation in providing approaches and strategies that center and elevate marginalized voices. In visualizing complexity, designers offer the security and active participation that can support Health Care Administrators in moving beyond data driven decision making.

Finally, in supporting communication and collaboration across all stakeholders the design research process collapses health silos creating the opportunity for communities to re-create themselves led by the voice and choice of the people who live the system: “It’s those voices that will inform and propel these traditional institutions into vibrant places where people thrive and to come to life, where they are heard and are treated in a way we should all be treated.”—VCH Health Leader.

References

Brooker, D.: What is person-centred care in dementia? Rev. Clin. Gerontol., 215–222 (2003)

CIHI.: Potentially inappropriate use of antipsychotics in long-term care (Percentage), 2018–2019 (2020). Retrieved from Canadian institute for health information: https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/inbrief.#!/indicators/008/potentially-inappropriate-use-of-antipsychotics-in-long-term-care/;mapC1;mapLevel2;/

Alzheimer Society Canada.: Alzheimer Society Canada (2017, June 7). Retrieved from use of antipsychotic medications to treat people living with dementia in long-term care homes: https://alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/files/national/media-centre/asc_position_06072017_antipsychoticmeds_e.pdf

Molloy, S.J.: Innovation labs in healthcare. Toronto, OCAD University (2018)

Anna Meroni, D.S.: Massive codesign: a proposal for a collaborative design framework. Milano, Open Access (2018)

Batalden, P.B., Davidoff, F.: What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare?. Qual. & Saf. Health Care 16(1), 2–3 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

Brown, A.M.: Emergent strategy. Chico, AK Press (2017)

Watkins, M.D.: Harvard Business Review (2007, September 7). Retrieved from Demystifying strategy: the what, who, how, and why: https://hbr.org/2007/09/demystifying-strategy-the-what#:~:text=Here’s%20my%20definition%3A%20A%20business,desired%20pattern%20of%20decisi

Ensiyeh Ghavampour, B.V.: Revisiting the “model of place”: a comparative study of placemaking and sustainability. Urban Plan., 196–206 (2019)

Alba Sánchez, J.C.-C.-L.: Multisensory stimulation for people with dementia: a review of the literature. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. & Other Dement., 7–14 (2013)

Heersmink, R.: The narrative self, distributed memory, and evocative objects. Philos. Stud., 1829–1849 (2018)

Ayse Sentürer, S.S.: A view to space and design through play: a research project at the architectural design studio. Int. J. Arch., Spat., Environ. Des., 41–51 (2016)

Helen Fisher, C.C.: Life cafe. Lab4Living. (n.d.). on%20making.&text=Together%2C%20the%20mission%2C%20network%2C,strategic%20direction%20for%20a%20business

Turkle, S.: Evocative objects—things we think with. Cambridge, MIT Press (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Boulton, L. et al. (2021). Scaling Participatory Methods for Cultural Change in Long Term Care Homes. In: Brankaert, R., Raber, C., Houben, M., Malcolm, P., Hannan, J. (eds) Dementia Lab 2021: Supporting Ability Through Design. D-Lab 2021. Design For Inclusion, vol 2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70293-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70293-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-70292-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-70293-9

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)