Abstract

This chapter discusses client and family experiences of care, i.e., person-centered care (PCC). Although PCC is a widely used concept, there are several dimensions to PCC that are not applied uniformly across studies. By embedding PCC into the Quality Health Outcomes Model (QHOM), characteristics and interventions influencing PCC outcomes can be explored at different levels, such as micro and macro. Further, the chapter describes the potential client, family, and system outcomes of PCC. Given the challenges of different conceptualizations of PCC and related concepts, PCC measures and methodological issues are discussed. Finally, the chapter provides suggestions and opportunities to tackle measurement and methodological challenges to improve PCC as an essential element of quality of care.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Person-centered care

- Micro-level interventions

- Macro-level interventions

- Client and family outcomes

- System outcomes

- Measures

- Methods

Introduction

Among patient-reported outcomes, patient and family experience of care has become an indicator of quality healthcare delivery (Goodrich and Cornwell 2008). One way of assuring optimal patient and family experiences is through the delivery of person-centered care (PCC), which is “care that is (1) respectful of and responsive to individual patients’ preferences, needs, and values and (2) ensuring that patients’ values guide all decisions” (Institute of Medicine 2001, p. 49). Although this is a clear definition of PCC, its conceptualization is less clear. There is a proliferation of terms used to describe PCC, such as negotiated and individualized care, patient-centered care, people-centered care, person-focused care, or whole-person-centered care (De Silva 2014). Additionally, PCC and patient satisfaction often are used interchangeably. However, patient satisfaction is an outcome of PCC (Dwamena et al. 2012; McMillan et al. 2013; Rathert et al. 2013) and should not be confused with the multidimensional concept of PCC.

A 2015 Delphi study identified five PCC dimensions: (1) patient as a unique person, (2) patient involvement in care, (3) patient information, (4) clinician-patient communication, and (5) patient empowerment (Zill et al. 2015). Although further dimensions can be added, these five core dimensions are the most consistently described in the literature. This chapter uses the above National Academy of Medicine (NAM) definition of PCC (Institute of Medicine 2001) and the five core dimensions (Zill et al. 2015) while changing the word patient to person to use PCC’s newest terminology (National Academies of Sciences 2018).

The concept of PCC can be applied to all settings (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes), service lines (e.g., medical, geriatric, pediatric, or psychiatric), and stages of care provision (e.g., admission, discharge). Patients with different diseases and various healthcare settings benefit from PCC, for instance, patients in rehabilitation care (Yun and Choi 2019) and patients with substance-use disorder (Marchand et al. 2019). However, due to PCC’s multidimensional nature, its provision is broadly recognized as challenging (De Silva 2014; Luxford et al. 2010). PCC is a crucial intervention to assure that quality care is delivered (Berwick 2009) and should be an essential part of quality improvement strategies. This chapter first links PCC to the QHOM and then discusses PCC interventions at different healthcare system levels. Outcomes impacted by PCC interventions are discussed. Further, client, family, and system characteristics are described. Challenges in measuring PCC are included, followed by implications and future directions.

Person-Centered Care: Linkages with the QHOM

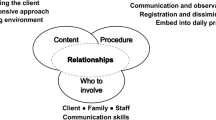

In the QHOM, PCC is an intervention that primarily impacts client and family outcomes, an essential part of delivering healthcare. PCC does not directly impact client and family outcomes but influences outcomes through system characteristics and client and family characteristics (see Fig. 12.1). There are bidirectional relationships between outcomes and client, family, and system characteristics and between these characteristics and the PCC interventions. Thus, continuous feedback loops are in place. Another unique feature is the multilevel dimensions of the QHOM. Through client, family, and system characteristics, PCC will influence not only client and family outcomes at the individual (micro) level, such as clients’ health status, but also outcomes at the system (macro) level, such as efficiency, responsiveness, and financial outcomes (National Academies of Sciences 2018).

Person-Centered Care Interventions

PCC interventions can be implemented at different levels of the healthcare system. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests using micro, meso, and macro levels (World Health Organization 2002). Although each of the levels interacts with one another, each has a distinct definition: micro is the patient or client level, meso is the organization or system level, and macro is the policy or environment level (Serpa and Ferreira 2019). In this section, interventions at the micro and macro levels are discussed. Meso-level system characteristics and interventions are discussed in Chap. 4, including adequate staffing, resources, and leadership.

Micro-level Interventions

Micro-level interventions that focus on the client and family address either a single PCC dimension or multiple dimensions. The multiple dimensions of PCC are mutually dependent. The dimensions patient involvement in care (dimension 2), patient information (dimension 3), and clinician-patient communication (dimension 4) can be viewed separately, but the three dimensions are also interconnected. Clients need information about diagnoses, treatment options, or alternative care processes to be involved in care. The information provides knowledge to be tailored to the clients’ care needs. Therefore, clinician-patient communication (dimension 4) that acknowledges the value of verbal and nonverbal communication skills plays an important role (Zill et al. 2015). Moreover, the four dimensions together are prerequisites for the PCC dimension, patient empowerment (dimension 5), which encourages self-management and self-care (Gerteis et al. 1991; Zill et al. 2015).

A recent review of systematic reviews investigated PCC interventions for clients and families (Park et al. 2018). Twenty-one reviews investigated client interventions; nine interventions targeted family members. The most common interventions for clients were focused on client empowerment, client information, and physical support (Park et al. 2018). Intervention for clients’ empowerment targeted clients’ motivation to take part in self-care and disease self-management. Other interventions were directed towards clients’ knowledge and skill development, such as risk factors and coping skills. Most family interventions focused on providing information and involvement of family members in care and decision-making processes (Park et al. 2018).

Macro-level Interventions

At the macro level, PCC interventions are mainly driven by broader healthcare policies and include payment incentives or penalties. For payment incentives, client and family processes and outcomes are often used. For instance, routine patient experience ratings are included in hospital performance comparisons alongside patient safety rates (see Chaps. 2 and 14 for more detail on incentives and hospital performance). Twenty-five percent of hospitals’ total performance scores are based on patient experiences (Medicare.gov. n.d.), which subsequently determines 1.75% of overall hospital payments from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Papanicolas et al. 2017). The better the hospital ratings from patients, the more the revenue hospitals receive. Therefore, one can argue that payment policies that include evaluating patient and family experiences of care are PCC interventions at the macro level.

Client and Family Characteristics

Client and family characteristics play a crucial role in PCC provision because they determine how interventions should be tailored to specific populations and, therefore, influence client and family outcomes. Demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, educational level) and clinical information (e.g., level of care dependency, type of disease) influence PCC outcomes. Further, both demographic and clinical data shape clients’ and families’ care preferences and care expectations, which are complex individual characteristics based on clients’ and families’ beliefs, values, and needs (Bowling and Rowe 2014). However, findings on what characteristics are important are inconclusive. For example, in one study, older patients tend to have fewer unmet expectations than younger patients (Shawa et al. 2017). In another study, Krupat et al. (2001) found that patients who were aged 60 and older, who were male, and who had a high school degree or less experienced less patient-centered care compared to younger, more educated, and female patients (Krupat et al. 2001). Whatever clients’ expectations are, though, the more expectations are met, the more positively they rate their experiences with care (Abdel Maqsood et al. 2012; Bowling et al. 2013).

Client and family culture also plays a role. A German cross-sectional study investigated the factors influencing patients’ perceptions of person-centered nursing care. Better self-rated health status and educational level of less than 9 years were associated with higher PCC ratings (Koberich et al. 2016). However, in an American secondary data analysis of patient PCC perceptions using the Oncology Patients’ Perceptions of the Quality of Nursing Care Scale, there were no associations between gender or age and nursing care ratings. At the same time, a lower educational level was associated with higher PCC ratings in oncology (Radwin 2003). Client characteristics have the potential to influence not only PCC interventions but also system characteristics. For example, patient acuity and care dependency level can influence nurse work environment elements, such as job stress, perceived workload, and care left undone (Wynendaele et al. 2019), which are all part of system characteristics.

System Characteristics

System or organizational characteristics affect how PCC interventions impact client and family outcomes. These characteristics include setting, as well as organizational barriers and facilitators. Healthcare settings (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes) and service lines (e.g., medicine, geriatric, pediatric, psychiatric) contribute to the heterogeneity and complexity of PCC interventions. For example, in hospital units caring for patients with dementia, PCC interventions differ substantially from those in pediatric acute care units. Although the core dimensions of PCC, (1) patient as a unique person, (2) person involvement in care, (3) person information, (4) clinician-person communication, and (5) person empowerment, are represented in both examples, care principles and processes will vary.

System characteristics have the potential to affect PCC interventions as both a barrier and a facilitator. Examples of barriers are traditional organizational practices and structures such as clinicians not having the ability to work autonomously, lack of rooms for private communication between clinician and client, and time constraints in the provision and education of PCC interventions. Other barriers are organizational and clinician attitudes, including lack of continuous attention and engagement with PCC routines, lack of client involvement and engagement in care and decisions, and lack of seeing the client as a whole person (Dellenborg et al. 2019; Gondek et al. 2017; Moore et al. 2017; Nkrumah and Abekah-Nkrumah 2019). Studies have shown the importance of appropriate organizational leadership (Bachnick et al. 2018; Bokhour et al. 2018; Gabutti et al. 2017), sufficient teamwork (Gabutti et al. 2017), and adequate staffing and resources (Bachnick et al. 2018; Jarrar et al. 2018; Zhu et al. 2018) for improvement of PCC provision and clients’ ratings of their experience.

However, organizational characteristics can also facilitate PCC interventions. For example, work environments that enable PCC interventions include strong leadership and management as role models for implementing PCC interventions. Additionally, continuous training opportunities that ensure that the organization has well-trained clinicians with a genuine knowledge of PCC interventions are essential for PCC interventions to succeed (Dellenborg et al. 2019; Gondek et al. 2017; Moore et al. 2017; Nkrumah and Abekah-Nkrumah 2019). Training should include approaches of clinicians whereby they emphasize PCC values, working practices, and interprofessional teamwork.

Outcomes Associated with Person-Centered Care Interventions

The heterogeneity and complexity of PCC interventions affect outcomes. Depending on the intervention’s focus (e.g., on one or more PCC dimensions), the outcomes naturally vary for both client and family outcomes and system outcomes.

Client and Family Outcomes

For PCC interventions, improved client and family outcomes are the goal. PCC interventions’ impact on client and family outcomes was examined in systematic reviews (Park et al. 2018). The findings suggested that although the PCC interventions were diverse, positive effects were found across many outcomes, including clients’ increased quality of life, satisfaction, confidence, and well-being and reduced levels of depression, burden, stress, and anxiety. For family members, the interventions improved knowledge, care skills, and confidence levels and lowered levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Park et al. 2018). In studies investigating specific client outcomes, the evidence is inconsistent. For example, studies with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome populations found improvements in self-efficacy (Cheng et al. 2017; Okrainec et al. 2017; Pirhonen et al. 2017). In contrast, studies with broadly defined patient populations did not show improved self-efficacy following PCC provision (Chiang et al. 2018).

System Outcomes

Inconsistent results are also typical with regard to system outcomes (i.e., clinical and economic). On the one hand, systematic reviews and individual studies assessing the effects of PCC interventions on system outcomes find reductions in unplanned visits and readmission rates in groups that received PCC interventions (Anhang Price et al. 2014; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Deek et al. 2016; Fiorio et al. 2018; Okrainec et al. 2017). On the other hand, studies correlating PCC with mortality rates have produced varying results (Chiang et al. 2018; Fiorio et al. 2018; Goldfarb et al. 2017). Because clinical outcomes influence economic outcomes, the evidence is similarly inconclusive regarding PCC interventions’ relationship with cost-effectiveness: some studies report that cost reductions accompany PCC interventions (Anhang Price et al. 2014; Fiorio et al. 2018; Stone 2008) while other studies found no effect (Olsson et al. 2013; Uittenbroek et al. 2018). A reason for the inconsistent evidence is not only the heterogeneity of the PCC interventions but also related to client, family, and system characteristics.

Challenges Measuring Person-Centered Care

Due to its multidimensional nature, the assessment, provision, and measurement of PCC are broadly recognized as challenging (De Silva 2014: Luxford et al. 2010). Challenges arise in the measurement of PCC with diverse instruments and methods but also its methodological weaknesses.

PCC Measures

A standard PCC measure does not exist (De Silva 2014), and available assessment instruments suffer from methodological weaknesses due to conceptualization issues and psychometric properties. Instruments claim to measure PCC experiences from patients’ perspective (Davis et al. 2008; Jenkinson et al. 2002; Suhonen et al. 2012b; Tzelepis et al. 2015), clinician’s perspectives (Sullivan et al. 2013), or a combination of both patient and clinician perspectives (De Silva 2014; Suhonen et al. 2012a). Additionally, some instruments measure the overall concept of PCC (Charalambous et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2008), whereas others measure only specific dimensions (De Silva 2014; Hudon et al. 2011; Phillips et al. 2015).

Regardless of the extent PCC dimensions are covered in an instrument, no widely used instrument accounts for patient preferences (Bachnick et al. 2021; Coulter and Cleary 2001). Patient preferences are a key element in the NAM definition of PCC, which is care that is “respectful of and responsive to individual patients’ preferences, needs, and values” (Institute of Medicine 2001, p. 49). Evaluating whether patients’ preferences are met requires two elements: assessing their preferences and ratings of the care they actually received to meet those preferences. Today there are no measures of either of those two elements in standard PCC instruments.

Many of the existing instruments measuring whether PCC is present have been tested psychometrically in specific settings, populations, and countries and therefore require adaptions in order to be used in other settings, populations, and countries (Cheng et al. 2017; Edvardsson et al. 2008; Radwin 2003; Suhonen et al. 2010). In the UK, the most commonly accepted patient experience instrument is the National Health Service (NHS) Adult Inpatient Survey, which is based on the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire (PPE-15) (De Courcy et al. 2012; Jenkinson et al. 2002; Leatherman and Sutherland 2007). In Switzerland, it is common for PCC instruments to include items from the PPE-15 and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) instrument (Ausserhofer et al. 2013; Bachnick et al. 2018; Bovier et al. 2004). The HCAHPS instrument was developed in the United States to measure patients’ general experience and satisfaction with care in various settings (AHRQ n.d.). Some argue that the HCAHPS is a PCC instrument (Cleary 2016), even though it only includes one of the five vital PCC dimensions: communication with clinicians.

Methodological Challenges

Questionnaire surveys are the most used method to measure PCC across different healthcare settings. The majority of PCC surveys have been developed by clinicians and researchers, with little or no patient involvement (Wiering et al. 2017). A scoping review of 190 studies found insufficient patient participation across studies. Not a single study involved patients in determining which outcomes should be measured (Wiering et al. 2017). However, nearly 60% of the studies involved patients in specific item development, most often through focus groups and interviews. To test comprehensibility, only half of the studies used cognitive interviews or other methods involving patients (Wiering et al. 2017). The findings support the position that outcome assessments such as the HCAHPS and the NHS instruments do not address elements important to clients. Similar results were found for Germany. A recently published Delphi study confirmed different opinions between clinicians and clients regarding the relevance of PCC dimensions (Zeh et al. 2019). These findings strengthen the argument that clients need to be involved in the development of PCC measures.

Indeed, lacking involvement of patients in the development of PCC measures might lead to measures with little or no actionable relevance for clinical practice or system redesigns. Another methodological challenge is that current PCC measures are challenging to utilize for benchmarking across healthcare organizations. For example, since 2009, the Swiss National Association for Quality Development in Hospitals (ANQ 2017) measure has been used to assess patients’ hospital stay experience. However, results show neither trends nor significant changes; with few exceptions, hospitals receive extremely high patient experience ratings (ANQ 2017). Such low variability can be explained in two ways. Swiss hospitals across the board deliver high-quality care, or the measure is not sufficiently sensitive to detect between-hospital differences. The latter explanation is most likely and indicates that the measure requires improvement.

Aside from the problem of distinguishing low- from high-performing organizations, a further question exists regarding the uneven influence of client and organizational characteristics, which are usually handled by using risk adjustment in comparisons (Abel et al. 2014; Orindi et al. 2016). Existing guidelines for risk adjustment recommend reporting both crude and adjusted values (AHRQ n.d.; NHS England Analytical Team (Medical and Nursing Analytical Unit) 2017; Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) 2009). However, there are variations in what and how risk adjustments are applied. A study from 2014 reviewed 142 organizations’ benchmark reports (115 hospitals and 27 physicians) and assessed whether each report specified the comparison methods used (Damberg et al. 2014). The level of detail varied widely, for instance, designation of the risk adjustment methods used (Damberg et al. 2014). Methods should be clearly stated to increase transparency, reliability, and overall credibility and discern whether differences are due to real differences in performance (van Dishoeck et al. 2011), for example, PCC interventions provided.

In summary, several systematic reviews have evaluated the evidence of PCC interventions and measurements. In general, the majority of studies were of low quality with methodological flaws including insufficient sample sizes (Rathert et al. 2013; Segers et al. 2019; Yun and Choi 2019), a wide diversity of measurements and interventions (Park et al. 2018; Rathert et al. 2013), inconsistent results (Yun and Choi 2019), and limited study comparison and generalizability (Barbosa et al. 2015; Dwamena et al. 2012; McMillan et al. 2013; Rathert et al. 2013). Although dozens of PCC studies are available, PCC assessment, implementation, and influence on outcomes remain unclear. Perhaps most importantly regarding PCC provision, the current conceptualization of PCC is too vague, resulting in unclear measures and, therefore, limited use for benchmark comparisons.

Implications and Future Directions

PCC is one key element of quality of care and affects all components of the QHOM. The provision of PCC interventions aims to improve client and family outcomes through client, family, and system characteristics. However, several client, family, and system characteristics influence how interventions affect client and family outcomes. Moreover, there are several challenges in the provision of PCC due to PCC’s complexity; heterogeneity of populations, interventions, and healthcare settings; and methodological challenges regarding PCC measures. The next steps in providing PCC interventions are the need to focus on both the interactions between PCC interventions and system characteristics and the methodological challenges, including developing appropriate PCC measures and common ways of measuring PCC.

When improving PCC provision through system characteristics, one must first identify where there are possibilities for change (Berwick et al. 2003). Therefore, future research has to focus on assessing system structures and processes that influence PCC delivery and clients’ experience of care. Such evidence will be crucial to inform quality improvement strategies and interventional research on facilitating factors or eliminating barriers to implementing PCC in healthcare settings.

Finally, in order to improve PCC, the methodological challenges surrounding PCC have to be acknowledged. For the current PCC measures, this includes how they are measured and how they are used. A starting point is to engage clients and families in measure development, and then assess what their preferences are and their ratings of the received care (Bachnick 2018). A balance between these two parameters indicates the provision of high levels of PCC; a gap indicates that patient preferences were not met, in other words, that lower levels of PCC were delivered. As this approach allows individual clients to register their preferences, its use will shed light on core PCC dimensions and, therefore, correct a significant shortcoming of current PCC conceptualizations. Only when PCC interventions are measured correctly can it be determined how clients’ and families’ care experience is optimized.

References

Abdel Maqsood AS, Oweis AI, Hasna FS (2012) Differences between patients’ expectations and satisfaction with nursing care in a private hospital in Jordan. Int J Nurs Pract 18(2):140–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02008.x

Abel GA, Saunders CL, Lyratzopoulos G (2014) Cancer patient experience, hospital performance and case mix: evidence from England. Future Oncol 10(9):1589–1598. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.13.266

Agency for Healthcare Reseach and Quality (n.d.) CAHPS Hospital Survey (H-CAHPS). https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/

Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Hays RD, Lehrman WG, Rybowski L, Cleary PD (2014) Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev 71(5):522–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558714541480

ANQ, Nationaler Verein für Qualitätsentwicklung in Spitälern und Kliniken (2017) Patientenzufriedenheit Akutsomatik, Erwachsene Nationaler Vergleichsbericht Messung 2016. https://www.anq.ch/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ANQ_Akut_Patientenzufriedenheit_Erwachsene_Nationaler-Vergleichsbericht_2017.pdf

Ausserhofer D, Schubert M, Desmedt M, Blegen MA, De Geest S, Schwendimann R (2013) The association of patient safety climate and nurse-related organizational factors with selected patient outcomes: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 50(2):240–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.007

Bachnick S (2018) Patient-centered care in Swiss acute care hospitals: addressing challenges in patient experience measurement and provider profiling. (PhD Nursing Science). University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland. https://edoc.unibas.ch/66825/1/Dissertation_S.Bachnick.pdf

Bachnick S, Ausserhofer D, Baernholdt M, Simon M, MatchRN Study group (2018) Patient-centered care, nurse work environment and implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals: a cross-sectional multi-center study. Int J Nurs Stud 81:98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.11.007

Bachnick S, Ausserhofer D, Baernholdt M, Simon M (2021) Preferences matter when measuring patient experiences with hospital care—a cross-sectional multi-center study. [Manuscript in Preparation]

Barbosa A, Sousa L, Nolan M, Figueiredo D (2015) Effects of person-centered care approaches to dementia care on staff: a systematic review. Am J Alzheim Dis Other Dement 30(8):713–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513520213

Bertakis KD, Azari R (2011) Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 24(3):229–239. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100170

Berwick DM (2009) What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff 28(4):w555–w565. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w555

Berwick DM, James B, Coye MJ (2003) Connections between quality measurement and improvement. Med Care 41(1 Suppl):30–38

Bokhour BG, Fix GM, Mueller NM, Barker AM, Lavela SL, Hill JN, Lukas CV (2018) How can healthcare organizations implement patient-centered care? Examining a large-scale cultural transformation. BMC Health Serv Res 18(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2949-5

Bovier PA, Charvet A, Cleopas A, Vogt N, Perneger TV (2004) Self-reported management of pain in hospitalized patients: link between process and outcome. Am J Med 117(8):569–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.020

Bowling A, Rowe G (2014) Psychometric properties of the new patients’ expectations questionnaire. Pat Exp J 1(1):111–130

Bowling A, Rowe G, McKee M (2013) Patients’ experiences of their healthcare in relation to their expectations and satisfaction: a population survey. J R Soc Med 106(4):143–149. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2012.120147

Charalambous A, Chappell NL, Katajisto J, Suhonen R (2012) The conceptualization and measurement of individualized care. Geriatr Nurs 33(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.10.001

Cheng L, Sit JWH, Choi KC, Chair SY, Li X, Wu Y, Tao M (2017) Effectiveness of a patient-centred, empowerment-based intervention programme among patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 79:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.021

Chiang CY, Choi KC, Ho KM, Yu SF (2018) Effectiveness of nurse-led patient-centered care behavioral risk modification on secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 84:28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.012

Cleary PD (2016) Evolving concepts of patient-centered care and the assessment of patient care experiences: optimism and opposition. J Health Polit Policy Law 41(4):675–696. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-3620881

Coulter A, Cleary PD (2001) Patients’ experiences with hospital care in five countries. Health Aff 20(3):244–252. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.244

Damberg CL, Sorbero ME, Lovejoy SL, Martsolf GR, Raaen L, Mandel D (2014) Measuring success in health care value-based purchasing programs: findings from an environmental scan, literature review, and expert panel discussions. Rand Health Quart 4(3):9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28083347

Davis S, Byers S, Walsh F (2008) Measuring person-centred care in a sub-acute health care setting. Aust Health Rev 32(3):496–504. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah080496. http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=AH080496.pdf

De Courcy A, West E, Barron D (2012) The national adult inpatient survey conducted in the English National Health Service from 2002 to 2009: how have the data been used and what do we know as a result? BMC Health Serv Res 12:71. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-71

De Silva D (2014) Helping measure person-centred care: a review of evidence about commonly used approaches and tools used to help measure person-centred care. https://www.swselfmanagement.ca/uploads/ResourceTools/Helping%20measure%20person-centred%20care.pdf

Deek H, Hamilton S, Brown N, Inglis SC, Digiacomo M, Newton PJ, Investigators FP (2016) Family-centred approaches to healthcare interventions in chronic diseases in adults: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs 72(5):968–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12885

Dellenborg L, Wikstrom E, Andersson Erichsen A (2019) Factors that may promote the learning of person-centred care: an ethnographic study of an implementation programme for healthcare professionals in a medical emergency ward in Sweden. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 24(2):353–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-09869-y

Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, Olomu A (2012) Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD003267. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2

Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Rasmussen B (2008) Swedish language Person-centred Climate Questionnaire—patient version: construction and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 63(3):302–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04709.x

Fiorio CV, Gorli M, Verzillo S (2018) Evaluating organizational change in health care: the patient-centered hospital model. BMC Health Serv Res 18(1):95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2877-4

Gabutti I, Mascia D, Cicchetti A (2017) Exploring “patient-centered” hospitals: a systematic review to understand change. BMC Health Serv Res 17(1):364. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2306-0

Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan DJ, Delbanco TL (1991) Introduction: medicine and health from the patient’s perspective. In: Through the patient’s eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, pp 1–13

Goldfarb MJ, Bibas L, Bartlett V, Jones H, Khan N (2017) Outcomes of patient- and family-centered care interventions in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 45(10):1751–1761. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002624

Gondek D, Edbrooke-Childs J, Velikonja T, Chapman L, Saunders F, Hayes D, Wolpert M (2017) Facilitators and barriers to person-centred care in child and young people mental health services: a systematic review. Clin Psycholol Psychother 24(4):870–886. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2052

Goodrich J, Cornwell J (2008) Seeing the person in the patient: the point of care review paper. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Seeing-the-person-in-the-patient-The-Point-of-Care-review-paper-Goodrich-Cornwell-Kings-Fund-December-2008.pdf

Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras ME (2011) Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med 9(2):155–164. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1226

Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Jarrar M, Rahman HA, Minai MS, AbuMadini MS, Larbi M (2018) The function of patient-centered care in mitigating the effect of nursing shortage on the outcomes of care. Int J Health Plann Manag 33(2):e464–e473. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2491. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29380909/

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S (2002) The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care 14(5):353–358. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12389801

Koberich S, Feuchtinger J, Farin E (2016) Factors influencing hospitalized patients’ perception of individualized nursing care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs 15:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0137-7

Krupat E, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Thom D, Azari R (2001) When physicians and patients think alike: patient-centered beliefs and their impact on satisfaction and trust. J Family Pract 50(12):1057–1062. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11742607

Leatherman S, Sutherland K (2007) A quality chartbook: patient and public experience in the NHS. The Health Foundation, New York

Luxford K, Piper D, Dunbar N, Poole N (2010) Patient-centred care: improving quality and safety by focusing care on patients and consumers discussion paper draft for public consultation. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/PCCC-DiscussPaper.pdf

Marchand K, Beaumont S, Westfall J, MacDonald S, Harrison S, Marsh DC, Oviedo-Joekes E (2019) Conceptualizing patient-centered care for substance use disorder treatment: findings from a systematic scoping review. Substan Abuse Treat Prevent Policy 14(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0227-0

McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, Kelly F, Wheeler AJ (2013) Patient-centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev 70(6):567–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558713496318

Medicare.gov (n.d.) Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html

Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, Naldemirci O, Elam M, Wolf A (2017) Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scand J Caring Sci 31(4):662–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12376

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine (2018) Crossing the global quality chasm: improving health care worldwide. Washington, DC. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25152/crossing-the-global-quality-chasm-improving-health-care-worldwide

NHS England Analytical Team (Medical and Nursing Analytical Unit) (2017) Statistical bulletin: overall patient experience scores; 2016 adult inpatient survey update. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/2017/05/31/overall-patient-experience-scores-2016-adult-inpatient-survey-update/

Nkrumah J, Abekah-Nkrumah G (2019) Facilitators and barriers of patient-centered care at the organizational-level: a study of three district hospitals in the central region of Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res 19(1):900. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4748-z

Okrainec K, Lau D, Abrams HB, Hahn-Goldberg S, Brahmbhatt R, Huynh T, Bell CM (2017) Impact of patient-centered discharge tools: a systematic review. J Hosp Med 12(2):110–117. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2692

Olsson LE, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, Ekman I (2013) Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials—a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 22(3-4):456–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12039

Orindi BO, Lesaffre E, Sermeus W, Bruyneel L (2016) Impact of cross-level measurement noninvariance on hospital rankings based on patient experiences with care in 7 European countries. Med Care 55(12):e150–e157. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000580

Papanicolas I, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Jha AK (2017) Patient hospital experience improved modestly, but no evidence Medicare incentives promoted meaningful gains. Health Aff 36(1):133–140. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0808

Park M, Giap TT, Lee M, Jeong H, Jeong M, Go Y (2018) Patient- and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 87:69–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.07.006

Phillips NM, Street M, Haesler E (2015) A systematic review of reliable and valid tools for the measurement of patient participation in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 25:130–131. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004357

Pirhonen L, Olofsson EH, Fors A, Ekman I, Bolin K (2017) Effects of person-centred care on health outcomes - A randomized controlled trial in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Health Policy 121(2):169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.12.003

Radwin LE (2003) Cancer patients’ demographic characteristics and ratings of patient-centered nursing care. J Nurs Scholarsh 35(4):365–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00365.x

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA (2013) Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 70(4):351–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774

Segers E, Ockhuijsen H, Baarendse P, van Eerden I, van den Hoogen A (2019) The impact of family centred care interventions in a neonatal or paediatric intensive care unit on parents’ satisfaction and length of stay: a systematic review. Intens Crit Care Nurs 50:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2018.08.008

Serpa S, Ferreira CM (2019) Micro, meso, and macro levels of social analysis. Int J Soc Stud 7:3. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v7i3.4223

Shawa E, Omondi L, Mbakaya BC (2017) Examining surgical patients’ expectations of nursing care at Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Eur Sci J 13(24)

Stone S (2008) A retrospective evaluation of the impact of the Planetree patient-centered model of care on inpatient quality outcomes. HERD 1(4):55–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758670800100406

Suhonen R, Berg A, Idvall E, Kalafati M, Katajisto J, Land L, Leino-Kilpi H (2010) Adapting the individualized care scale for cross-cultural comparison. Scand J Caring Sci 24(2):392–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00712.x

Suhonen R, Efstathiou G, Tsangari H, Jarosova D, Leino-Kilpi H, Patiraki E, Papastavrou E (2012a) Patients’ and nurses’ perceptions of individualised care: an international comparative study. J Clin Nurs 21(7-8):1155–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03833.x

Suhonen R, Papastavrou E, Efstathiou G, Tsangari H, Jarosova D, Leino-Kilpi H, Merkouris A (2012b) Patient satisfaction as an outcome of individualised nursing care. Scand J Caring Sci 26(2):372–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00943.x

Sullivan JL, Meterko M, Baker E, Stolzmann K, Adjognon O, Ballah K, Parker VA (2013) Reliability and validity of a person-centered care staff survey in veterans health administration community living centers. Gerontologist 53(4):596–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns140

Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) (2009) Erhebung, Analyse und Veröffentlichung von Daten über die medizinische Behandlungsqualität: empfehlungen [The collection, analysis and publication of data about quality of medical treatment: recommendations]. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 90(26/27):1044–1054

Tzelepis F, Sanson-Fisher RW, Zucca AC, Fradgley EA (2015) Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Pat Prefer Adher 9:831–835. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S81975

Uittenbroek RJ, van Asselt ADI, Spoorenberg SLW, Kremer HPH, Wynia K, Reijneveld SA (2018) Integrated and person-centered care for community-living older adults: a cost-effectiveness study. Health Serv Res 53(5):3471–3494. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12853

van Dishoeck AM, Lingsma HF, Mackenbach JP, Steyerberg EW (2011) Random variation and rankability of hospitals using outcome indicators. BMJ Qual Saf 20(10):869–874. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048058

Wiering B, de Boer D, Delnoij D (2017) Patient involvement in the development of patient-reported outcome measures: a scoping review. Health Expect 20(1):11–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12442

World Health Organization (2002) Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/

Wynendaele H, Willems R, Trybou J (2019) Systematic review: association between the patient-nurse ratio and nurse outcomes in acute care hospitals. J Nurs Manag 27(5):896–917. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12764

Yun D, Choi J (2019) Person-centered rehabilitation care and outcomes: a systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 93:74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.012

Zeh S, Christalle E, Hahlweg P, Harter M, Scholl I (2019) Assessing the relevance and implementation of patient-centredness from the patients’ perspective in Germany: results of a Delphi study. BMJ Open 9(12):e031741. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031741

Zhu J, Dy SM, Wenzel J, Wu AW (2018) Association of magnet status and nurse staffing with improvements in patient experience with hospital care, 2008–2015. Med Care 56(2):111–120. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000854

Zill JM, Scholl I, Harter M, Dirmaier J (2015) Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter?—results of a web-based expert Delphi survey. PLoS One 10(11):e0141978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141978

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bachnick, S., Simon, M. (2021). Client and Family Outcomes: Experiences of Care. In: Baernholdt, M., Boyle, D.K. (eds) Nurses Contributions to Quality Health Outcomes. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69063-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69063-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-69062-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-69063-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)