Abstract

Our capacity to pay attention—to employ top-down attention by directing our focus toward one idea or task while excluding from our consciousness a host of competing stimuli and thoughts—is key to every human achievement. But top-down attention is a limited resource that fatigues with use. Research demonstrates that having contact with nature, even in otherwise dense urban settings, can restore our ability to focus. Thus, access to natural elements in the form of parks, interconnected green corridors, street trees, rain gardens, green roofs, and green walls do more that provide attractive places for people to live, work, and play. They help people recover from the attentional fatigue that is part of everyday life. In doing so, these landscape elements help us achieve our goals in life. One implication of these findings is that we should redouble our efforts to ensure that we provide nature at every doorstep.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

2.1 Introduction

Our ability to pay attention—that is, to engage top-down attention—underlies every human achievement. It is fundamental to learning, problem-solving, perseverance, and planning. It is necessary to maintain an ongoing train of thought, set goals, initiate and carry out tasks, monitor and regulate one’s behavior, and to function effectively in social situations.

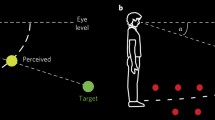

Unfortunately, top-down attention has become an increasingly taxed resource in our modern society. The explosion of information and ubiquity of digital communication and digital media have placed unprecedented cognitive demands on humans (Jackson, 2008, p. 14). In the face of this onslaught of information (Fig. 2.1), we have yet to recognize the importance of protecting and restoring our capacity to direct our attention. Just as we agree that measures need to be taken to restore natural resources (e.g., air, water, habitats, ecosystems) we need evidence-based discussions regarding our capacity to restore our attentional functioning after becoming mentally fatigued.

Our modern world requires us to pay attention to a constant stream of information. This relentless torrent of information impacts our ability to focus. To what extent does exposure to nature—even the kind of nature we find in cities—help people recover from the mental fatigue that results for the unremitting river of information we face today? Photo by author

The two main points we make in this chapter are often under-valued. First, although top-down attention is fundamental to human success, it also fatigues with use (Faber, Maurits, & Lorist, 2012; Kaplan & Berman, 2010). While all of us have experienced this mental fatigue, we may not be aware of the price it exacts in terms of our effectiveness. When we are mentally fatigued, we have difficulty focusing and concentrating, our memory suffers, we miss subtle social cues, we are more likely to be impulsive and jump to conclusions.

Second, exposure to nature can support the process of restoring our attention and thus improve our effectiveness in almost every human endeavor. Below, we describe what we mean by contact with nature, especially as it relates to urban dwellers. Next, we describe how contact with nature impacts our capacity to pay attention and focus on the important role green settings have in restoring our attentional functioning. At the end of this chapter, we consider the implications of these ideas for supporting attention.

2.2 Nature

There is evidence that the general public conceives the world as consisting of features that are either “human made” or “natural” (Lindland, Fond, Haydon, & Kendall-Taylor, 2015). Within this dichotomy, urban settings are seen as the prototypical example of human-made and “pure” wilderness epitomizes the natural. Like most landscape architects, ecologists, parks managers, and urban foresters, however, we see the natural world as a continuum spanning from settings devoid of natural elements (e.g., vegetation, water, and animals) to wilderness settings. Cities fit within this continuum because they can contain nature in the form of the urban forests, street trees, parks, rain gardens, green roofs, vegetable or flower gardens, and bioswales. That is, experts see nature that has been designed and maintained by human hands as fully natural.

It is this conception of nature that we employ below. Indeed, we are particularly interested in nearby nature. That is, nature that is visible and accessible outside people’s homes, schools, and workplaces.

2.3 Attention

Attention is the process of “taking possession by the mind,” or the “withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others” (James, 1890, p. 403). Our capacity to pay attention is one of our most powerful and essential resources. As anyone who has ever written a funding proposal or syllabus, graded final exams, planned a budget, solved a complex social problem, or even planned a vacation can attest, one’s ability to pay attention is not only limited, it is also essential to accomplishing all our goals. As initially described by William James (1892), humans have two modes of attending to information: passive or involuntary attention and voluntary or directed attention, now often referred to as bottom-up and top-down attention.

2.3.1 Bottom-Up Attention

The first mode of attention is easy, effortless, and involuntary. Some objects, ideas, landscapes, and situations are effortlessly engaging and require no work as we take them in. This mode, called bottom-up attention, includes attending to things that are fascinating (Kaplan & Berman, 2010; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). Think of watching birds outside your window (Fig. 2.2), a waterfall, or a wild dog that has just crossed your path. When sitting by the waterfall, you don’t make a conscious decision to pay attention to the water. On the contrary, you most often find yourself absorbed by the movement of the water before you are aware of it.

There are a host of things and activities that are fascinating for humans. Some of these are softly fascinating—gardening, bird watching, walking in the woods. Attending to softly fascinating things allows you to carry out some task, working in the garden for instance, without filling your head—that is, you can pull weeds or turn the soil and still retain the capacity to think other thoughts. Other objects and activities are so fascinating that they completely absorb you and thus leave no capacity for thinking about other things. This so-called hard fascination includes such things as intense competitions, many television programs and movies, an object flying toward your head, and most forms of aggression and violence. No matter how interesting you find this chapter, if a fight broke out nearby as you are reading it, you would have to employ an extraordinary effort to focus your attention on your reading rather than watching the conflict play out.

2.3.2 Top-Down Attention

The second mode of attending to information requires one to pay attention (or concentrate). Paying attention requires effort (Kaplan & Berman, 2010). Paying attention allows you to manage your thoughts and emotions, including keeping information in mind as you use it, multitasking and switching between tasks, choosing what features to focus on, and being able to resist distractions (Katsuki & Constantinidis, 2014). In order to pay attention to this chapter, for instance, you have to exclude from your awareness two sources of distraction: activities and sensory input from your surrounding environment (e.g., the video in the background, the noise from children playing, the new text on your phone) and all the thoughts that are running around in your head. After a period of paying attention, your ability to keep these distractions at bay fatigues and it becomes harder and harder to keep your mind on the task at hand (Kaplan, 1995).

2.3.3 Mental Fatigue

Concentrating in this way—that is, expending effort to pay attention—for an extended period of time leads to mental fatigue (Faber et al., 2012). In order to engage top-down attention, we must block out distractions from the things going on around us and from the thoughts that are constantly swirling in our heads. The mechanism that blocks these distractions fatigues with use and after a while, it becomes increasingly hard to focus, make decisions, and remain at ease (Kaplan & Berman, 2010). This fatigue occurs even for topics that you enjoy and in which you want to engage (e.g., playing chess, planning a vacation, solving a puzzle), as well as for topics that feel like hard work (e.g., grading essays, preparing a proposal). There is no shortage of opportunities for us to become mentally fatigued. We live with a constant torrent of information at work and, increasingly, in our leisure activities too, much of it designed to make us take some action that may be counter to our goals.

The costs of mental fatigue can be considerable (Sullivan & Kaplan, 2016). A person who cannot focus their attention is likely to miss important details and have trouble remembering details. Compared to someone who is not mentally fatigued, a person with low attention functioning is more likely to be irritable, have trouble with self-management, struggle to resist temptations, and miss subtle social cues. When a person is mentally fatigued, they are less effective in pursuing goals and interacting with others (Kaplan, 1995). A person with depleted attention is more likely to say or do things they might later regret, which can impact relationships, work performance, and even personal goals such as losing weight or saving money. In short, we are not at our best when our attention is depleted (Kaplan & Berman, 2010; Kaplan & Kaplan, 2003; Kuo & Sullivan, 2001; Poon, Teng, Wong, & Chen, 2016; Sullivan & Chang, 2011).

The cluster of symptoms associated with mental fatigue is important for at least two reasons. First, just about everything we seek to accomplish depends on our ability to engage our top-down attention. This includes accomplishing things that range from the mundane (e.g., getting to dinner on time) to things we care deeply about but with which we often struggle (e.g., responding to a loved one by actually listening, being a good and consistent parent, treating others with respect and kindness, coming up with a creative solution to a problem, making a difference in the world). Put another way, being able to pay attention is fundamental to functioning effectively in all aspects of life and to accomplishing everything we care about achieving.

Second, it is important because when individuals are mentally fatigued, they are often in an emotional state that works against their capacity to accomplish their goals. Mentally fatigued individuals are likely to experience emotional dysregulation and have difficulty modifying their emotional state toward goal-oriented behaviors. Mentally fatigued individuals are likely to feel irritable and impulsive—two of the most common side effects of mental fatigue (Kaplan, 1995). Compared to when you are not mentally fatigued, it is significantly more difficult to come up with a creative solution or listen with patience and respond with respect when you are mentally fatigued. Thus, being mentally fatigued reduces our competence and effectiveness in many domains.

Thus far, we have seen that we have two modes for paying attention. One takes little effort (bottom-up attention) and is not subject to fatigue. The other requires considerable effort (top-down attention) and is subject to fatigue. When we are mentally fatigued, we are in a state that works against our effectiveness or our capacity to achieve our goals. Next, we consider how contact with nature impacts mental fatigue.

2.4 Attention Restoration Theory

Attention Restoration Theory (ART) postulates that contact with nature helps people recover from mental fatigue. According to ART, having a view to a landscape that contains natural elements (e.g., trees, flowers, water), or actually being in such a landscape for a few minutes can restore your capacity to focus because it provides the mechanism necessary to block distractions an opportunity to rest and restore (Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan, Kaplan, & Ryan, 1998).

Think for a moment about a time when you were mentally fatigued—you may have just finished a major project, or perhaps you had simply been going about your daily routine. Now, imagine a place that would be restorative, a place that would allow you to clear your head and regain your capacity to focus, see things clearly, and feel on top of your game. ART proposes that such a restorative place should (1) allow you to be away physically or mentally from your everyday routine; (2) offer soft fascinations that effortlessly holds your attention; (3) provide you a sense of extentor being connected to a larger spatial or temporal world; and (4) be compatible with your purposes and facilitate achievement of your goals. A natural setting—even an urban setting that contains vegetation—often fulfills all these characteristics.

Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) have observed that these four characteristics of restorative places (being away, extent, fascination, and compatibility) are often available in green settings. Certainly, landscapes rich in nature are not the only settings that can relieve top-down attention fatigue. Compared to other interventions, however, seeking access to nature, even in urban settings, may be an effective way for individuals across various populations to restore their top-down attention. If that is the case, then gaining exposure to nature, especially green settings, on a regular basis, should have a positive impact on attention restoration. Is there evidence in support of such predictions?

2.5 Evidence Examining Attention Restoration Theory

ART postulates that contact with green landscapes should assist recovery from mental fatigue because green settings draw primarily on bottom-up attention, allowing top-down attention to rest and restore (Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). Over the past quarter century, the number of empirical studies examining this relationship has been on the rise, reaching unprecedented levels in the recent few years. One review of evidence regarding nature and attention restoration reported some support (Ohly et al., 2016), while another review reported considerable support for ART (Stevenson, Schilhab, & Bentsen, 2018). Our literature review of recently published, peer-reviewed journal articles differs in emphasis from these prior reviews in that we aimed to assess only empirical studies that were driven by ART and to discuss possible reasons when the directions of the findings diverge. Accordingly, rather than use of a typical keyword search syntax developed around key constructs, we took a citation chaining approach and started with a forward citation search. Below, we present the process by which we conducted the review, summarize our findings, and give some examples from additional studies that were stimulated by ART.

2.5.1 Literature Review Criteria and Screening

We included published studies that met the following criteria:

-

The paper cited Kaplan’s (1995) publication on ART.

-

The main outcome included at least one objective measure of attention.

-

The study design allowed some level of causal inference: experimental, quasi-experimental, or cohort study, including prospective and retrospective studies.

-

The main intervention or explanatory variable involved variation in exposure to nature or urban green space.

-

The study was published in English between 2011 and 2018.

-

The article appeared in a peer-reviewed journal.

In order to identify recent articles that were grounded in ART, we took a citation chaining approach and searched forward for literature that cited Kaplan (1995). We identified articles by searching the Web of Science, Scopus, PsychInfo, and Google Scholar. For those databases that allowed search refinement, we specifically identified studies with a measure of attention by refining on the following keywords or phrases:

-

Attention*

-

Concentrate*

-

Cogniti*

-

Executive function*

-

Working memory

-

Executive control

The original search yielded 1595 articles, of which 1004 contained the abovementioned keywords pertaining to attention. Those articles were subjected to title and abstract screening, after which 130 articles remained under consideration. We then conducted a full-text review of those 130 articles and selected 48 to be included. During the title, abstract, and full-text review steps, we excluded studies where the outcomes or measures were not directly related to attention. Thus, we excluded studies that focused on measures of vitality, academic performance, physical activity, social support, stress, neuroticism, time perception, creativity, and long-term memory. We also excluded studies that relied solely on self-reports of attention, such as ones that used the Perceived Sensory Dimension scale (PSD), Self-Rating Restrictiveness Scale (SRRS), Perceived Restorative Scale (PRS), Restorative Outcome Scale (ROS), or Self-Reported Restrictiveness scale (SRR). In addition, we excluded studies that used scenario-based assessments in which participants were instructed to imagine a particular environment or activity. Finally, we excluded studies that evaluated treatments not directly related to nature (e.g., lighting conditions, building or indoor architectural designs, music treatments, or cultural heritage site visits). In the case of multiple articles reporting results from a single study, only one was included. Table 2.1 describes the included studies and their characteristics.

2.5.2 Characteristics of the Included Studies

Of the 48 articles included in our analysis, almost half (23 studies) were published in 2017 and 2018, suggesting an increasing trend in publications focused on ART (Fig. 2.3). The majority examined adults (37 studies), but studies investigating attention restoration in children are on the rise; in 2017 and 2018 alone, eight articles reported effects on children within varying developmental phases. About half (24 studies) included university students or university staff members. Only one study concerned older adults. Most studies included participants from the general population; five included populations that either are formally diagnosed with or have self-perceived physical or mental health disorders such as major depressive disorder, exhaustion disorder, chronic heart failure, or depressive or stress symptoms.

All but two of the 48 included studies employed experimental or quasi-experimental research designs; the exceptions used longitudinal designs to investigate developmental outcomes in children. Most of the experimental and quasi-experimental studies employed treatments focused on the physical environment—that is, real places experienced by being immersed or through sense of sight (28 studies); about one-third used photos, videos, or some other form of simulation-based stimuli that varied in terms of natural content or exposure to nature (18 studies). Four experimental studies used a combination of physical and simulation treatments. Taken as a whole, the included studies encompass a wide variety of outdoor and indoor experiences and therefore are diverse in the types of exposure to nature that participants received. These types of exposure included outdoor classes and recesses, outdoor exercise or play sessions, outdoor sitting or quiet relaxation, outdoor walking, outdoor or wilderness experiences, and indoor activities in proximity to plants or with window views of nature.

The most frequently used nature treatments were classic ones: variation in nature exposure as seen through a window view and variation in nature exposure during an outdoor walk. Across all experimental or quasi-experimental studies, the duration of a single treatment session ranged from less than 1–90 min, with a median of 10 min. For studies that involved exposure to physical settings, the median duration of exposure was 30 min. For studies that involved simulations, the median duration of exposure was considerably lower at 6.5 min.

The included studies also employed a wide variety of neuropsychological assessments to objectively measure attention. About one-third used digit span forward or backward (17 studies). When considering digit span combined with reading, visual, or spatial span (6 studies), the use percentage grows to just under half. Other popular tests were the go/no-go or sustained attention to response task (5 studies), attention network task (4 studies), Necker cube pattern control task (4 studies), Stroop test (4 studies), and the trail making task (4 studies). Thirteen other tests were used at least once in the set of included studies.

2.5.3 Findings

Overall, findings from these studies show considerable support for Attention Restoration Theory. Among the 48 studies, 28 (58%) demonstrated clearly positive effects of nature exposure on attention. An additional 13 (27%) identified positive effects for a particular group in terms of one or more measures of attention. Meanwhile, although six articles (12%) had no significant results, only one article reported negative associations between nature exposure and attention.

The study with the sole negative finding (Burmeister, Moskaliuk, & Cress, 2018) had participants experience virtual reality scenes, either an indoor office or an outdoor recreational scene, before measuring their attention via the Psychomeda Konzentrations test (KONT-P). As the aim of the study was to assess work-related concentration, it may be that the indoor office setting was more compatible with the expectations of a work setting than the outdoor recreation scene, hence the negative finding. The KONT-P test used to assess work-related concentration may also differ in psychometric attributes compared to other scales.

In examining the effects of physical versus virtual nature experiences on attention, we found that physical nature tended to incur more positive attentional functioning (Table 2.2). However, the difference between physical and virtual experiences was not statistically significant by Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.23). We also investigated the extent to which different types of neuropsychological tests accounted for differing results between studies. As a wide variety of tests were used in the set of included studies, we broadly used three main categories of cognition and attention that were assessed: working memory, sustained and selective attention, and visual scan or processing speed (Table 2.3). More than one of these aspects can be simultaneously assessed by a given test; for example, the Stroop test assesses both selective attention and processing speed. Analysis based on these aspects revealed that those studies that assessed working memory had a slightly greater tendency to yield positive associations than those evaluating the other two aspects. These differences, however, did not reach statistical significance by Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.62).

In summary, we identified a recent rise in studies examining the effects of nature on attention restoration, especially in vulnerable populations such as children and patients with mental health disorders. Recent studies also explored a wide variety of nature exposures or activities while participants were in natural settings. We found strong support for ART across populations, types of nature exposure, and different neuropsychological tests of attention. Because we aimed to trace studies that build upon and test ART, the search and screening protocol used here differed from that of a standard systematic review. As such, the articles reviewed may not form an exhaustive list of studies that examine the effects of nature on attention and our findings can complement recent systematic reviews on similar topics (Ohly et al., 2016; Stevenson et al., 2018).

2.5.4 Some Specific Examples

Quite a number of studies have examined the impacts of green landscapes on attention and the outcomes are clear. Exposure to green landscapes is likely to boosts a person’s capacity to pay attention. The findings come not only from very green settings such as large and small forests (Shin, Shin, Yeoun, & Kim, 2011; Sonntag-Öström et al., 2014), rural areas (Roe & Aspinall, 2011), wilderness settings (Hartig, Mang, & Evans, 1991), and prairies (Miles, Sullivan, & Kuo, 1998), but also from more modestly green settings such as community parks (Fuller, Irvine, Devine-Wright, Warren, & Gaston, 2007; Korpela, Ylén, Tyrväinen, & Silvennoinen, 2008), schools (Li & Sullivan, 2016; Matsuoka, 2010; Wu et al., 2014), and neighborhoods (Kuo & Sullivan, 2001; Taylor, Kuo, & Sullivan, 2001; Wells, 2000).

In one fascinating study, attention of adults was assessed in a University of Michigan laboratory (Berman, Jonides, & Kaplan, 2008). Following the assessment, each participant was asked to walk for 50 min in either downtown Ann Arbor (a small city) or in the University arboretum (a large green landscape with many trees). When they returned from their walk, their attention was assessed again. The following week, these individuals came back to the lab and repeated the same activities except those had who originally walked downtown walked in the arboretum and vice versa. The results were compelling. After the walk in the arboretum, participants’ attentional performance improved by 20%, but no gains in performance were found after the walk downtown. A 20% improvement in one’s capacity to pay attention is no trivial matter! It is on the order of a clinical dose of attention-deficit drugs such as Ritalin, Adderall, or Dexedrine. In other words, a 20% increase in attentional performance is a huge increase that will certainly have significant implications for a person’s functioning.

Such an effect is not limited to adults, nor does it occur only when an individual spends time physically under trees. A study conducted by our group examined the extent to which having a view onto a green space would produce significant attention restoration for high school students who engaged in mentally fatiguing academic activities (Li & Sullivan, 2016). Students were randomly assigned to a classroom with three window conditions, i.e., window with a view onto a green space, window with a view onto a barren space, and no window at all. They were asked to perform a set of academic tasks, and then take a 10-min break in the classroom. When comparing their attentional performance, there was no difference among the groups at the end of the academic tasks: all groups’ performance declined after the tasks. However, after the 10-min break, the group with a green window view performed significantly better than before the break and significantly better than the other two window treatments.

Is the effect of green landscapes on attention available to everybody or only a small segment of the population? The evidence from the literature shows that a wide variety of people benefit from exposure to green spaces (see an example of such a space in Fig. 2.4). Studies have demonstrated links between green spaces and higher performance on attentional tasks among public housing residents, AIDS caregivers, cancer patients, college students, prairie restoration volunteers, and employees of large organizations.

Perhaps most strikingly, children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been found to benefit from exposure to urban parks and other green spaces near their homes. In a series of studies, such access has been consistently linked with a reduction in ADHD symptoms (Kuo & Taylor, 2004; Taylor et al., 2001; Taylor & Kuo, 2009). In findings similar to those in the University of Michigan study describe above, Taylor and Kuo report that children with ADHD concentrated significantly better after the walk in a park than after the walk downtown or in a neighborhood (2009).

The prevalence of smart phones and social media in our society raise another question about the effects of nature on attentional performance. When we talk about spending time in nature, we imply that any kind of activity in nature would help recovering from mental fatigue. However, one of our recent studies demonstrated that using an electronic device counteracts the attention restoration effects of nature. Participants who used their laptops in a green condition did not experience attention restoration (Jiang, Lee, & Sullivan, 2019).

In sum, there is considerable evidence to show that exposure to a green landscape—such as a walk in an urban park or a view to a green area outside a school window—is likely to reduce symptoms of mental fatigue. Evidence from a wide variety of settings and a great diversity of populations provides support for this conclusion, which surely has important implications for how we plan and design landscapes at a variety of scales. However, having an accessible green space or spending time there does not guarantee attention restoration. In the digital age, exposure to nature can be a powerful prescription to mental fatigue caused by the flux of information, but only if you are not using your phone while trying to recover.

2.6 Suggestions for Supporting Attention

We live in an information intensive world that requires us to engage our top-down attention and focus on a great number of things during nearly all our waking hours. Many of us also work in settings in which we are expected to respond to information quickly, whether we are at work or not. Such requirements put great demands on our attention and result in many of us feeling mentally fatigued a good deal of our adult lives.

If you find yourself mentally fatigued more often than you would prefer, you might consider running a small experiment or two. Small experiments involve paying attention to the impacts of small changes in the way you go about doing things (Irvine & Kaplan, 2001). You can run an experiment to see how modest changes in your life impact your ability to prevent or recover from mental fatigue. Here are some possibilities to consider.

2.6.1 Seek Out Nature

One of the most consistent findings from the research inspired by Attention Restoration Theory is that having regular contact with natural settings—including urban settings with green elements—has important consequences for your attentional functioning. That’s because being in or looking at nature engages our bottom-up attention and thus allows our top-down attention to rest and restore.

You might explore the possibility that regular exposure to green spaces has tangible benefits for you personally. Perhaps that means re-arranging your office so you have a view to nature from your desk. Or maybe you can take a short walk a couple of times per day along a tree-lined street or in a nearby park. A vase with some flowers or some potted plants near your work space might have an impact. So too, might a poster-sized picture of a landscape that you like. The findings summarized above suggest that having a view to a real landscape, or perhaps better still, being in a green space, will have the most positive impact on your top-down attention.

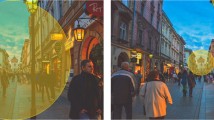

2.6.2 Create More Urban Nature

You can support your attentional functioning and make an investment in your attentional functioning in the future by taking steps to create more nearby urban nature (see, for example, Fig. 2.5). Many urban neighborhoods lack street trees and parks. Too often school grounds consist of paved parking lots that lack vegetation. What happens when you work with your neighbors and community activists to seek more funding for urban parks, insist that trees be planted in neighborhoods, and help make it possible for every child to go to a school that provides daily access to nature? There is a rich set of possible small experiments to run related to creating more nature.

Green spaces in urban settings contribute to the ecological health and functioning of places and often to their beauty. Perhaps, just as importantly, they also contribute to the ability of people to achieve their goals in life because these green places help people recover from mental fatigue. Photo by author

2.6.3 Eliminate Distractions

Top-down attention makes the task you are focusing on more salient while dampening down two sources of distraction—(1) all the activities going on in the world around you and (2) all the thoughts swirling around in your head at any moment. The distractions in the physical world are seemingly endless. We get an alert when a new email arrives. Our phones vibrate when some distant friend posts on social media that they have enjoyed a meal. It vibrates again a minute later with an alert that a new podcast is available, or when there is a new weather forecast, sports score, or news of any sort. Any one of these distractions may seem trivial, but over the course of the day, they wear us down and reduce our effectiveness. These distractions fill our heads with ideas and issues that are almost always disconnected from our goals. And they produce invisible costs by making us more distracted, irritable, error-prone, and fatigued.

Can you run other experiments to get a sense of the extent to which eliminating distractions in your physical environment improves your ability to focus? What happens when you turn off all notifications and alerts for a period of hours? How effective are you when you work in a quiet place where you are not disturbed?

But what about the second source of distractions—all the distractions that come from your own mind? These are distractions that pull you away from the task at hand while your mind wanders to a conversation you had earlier, your plans for tonight, your hopes that you can solve that tricky social dilemma, or one or another of the limitless possibilities that spring up from our minds. To address this challenge, you might try mindfulness meditation. There is a growing body of evidence showing that mindfulness meditation increases one’s capacity to stay on task (Jha et al., 2019), remember details better (Levy, Wobbrock, Kaszniak, & Ostergren, 2011), and reduce mind-wandering, worrying, and poor attention (Sood & Jones, 2013). And one does not have to be a Zen Master to see the benefits of mindfulness meditation—a few days of practice may be enough to increase attentional functioning (Chiesa, Calati, & Serretti, 2011; Zeidan, Johnson, Diamond, David, & Goolkasian, 2010).

2.7 Conclusion

Exposure to natural settings (Fig. 2.6), even in the midst of urban settings, helps restore and replenish a resource that is essential to functioning in our modern world: our ability to engage our top-down attention. Spending time in nature near your home, work, or school, or even having a view to a natural setting through a window restores depleted top-down attention.

Landscapes that have the largest impact on helping people recover from mental fatigue are easily accessible. They can be seen from an office or home or are a close walk away. Research suggests that daily contact with nature is an effective way to reduce mental fatigue and support your attentional functioning

The consequences of alleviating typical levels of mental fatigue are far-reaching and consequential. When you are mentally fatigued, you are not at your best for accomplishing your goals or supporting your relationships. That’s because mentally fatigued individuals are more prone to making errors, missing subtle social cues, impulsivity, and irritability (Kaplan, 1995).

Research shows that regular contact with nature, even urban nature—places with trees, grass, rain gardens, and the like—helps people recover from mental fatigue and this has far-reaching benefits for individuals, families, and communities (Kuo & Sullivan, 2001; Li, et al., 2019; Li, Chiang, Sang, & Sullivan, 2019). These urban green spaces need not be large or pristine to aid recovery from mental fatigue. They must, however, be easily accessible from a person’s home or workplace.

Access to natural elements in the form of parks, interconnected green corridors, street trees, rain gardens, green roofs, and green walls do more that provide attractive places for people to live, work, and play. They help people recover from the attentional fatigue that is part of everyday life. In doing so, these landscape elements help us achieve our goals in life. One implication of these findings is that we should re-double our efforts to ensure that we provide nature at every doorstep.

References

Abbott, L. C., Taff, D., Newman, P., Benfield, J. A., & Mowen, A. J. (2016). The Influence of Natural Sounds on Attention Restoration. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 34(3), 5–15.

Amicone, G., Petruccelli, I., De Dominicis, S., Gherardini, A., Costantino, V., Perucchini, P., et al. (2018). Green breaks: The restorative effect of the school environment’s green areas on children’s cognitive performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1579.

Bailey, A. W., Allen, G., Herndon, J., & Demastus, C. (2018). Cognitive benefits of walking in natural versus built environments. World Leisure Journal, 60(4), 293–305.

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207–1212.

Berman, M. G., Kross, E., Krpan, K. M., Askren, M. K., Burson, A., Deldin, P. J., et al. (2012). Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(3), 300–305.

Bourrier, S. C., Berman, M. G., & Enns, J. T. (2018). Cognitive strategies and natural environments interact in influencing executive function. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1248.

Bratman, G. N., Daily, G. C., Levy, B. J., & Gross, J. J. (2015). The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, 41–50.

Brez, C., & Sheets, V. (2017). Classroom benefits of recess. Learning Environments Research, 20(3), 433–445.

Burmeister, C. P., Moskaliuk, J., & Cress, U. (2018). Office versus leisure environments: Effects of surroundings on concentration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 58, 42–51.

Chen, Z., He, Y., & Yu, Y. (2016). Enhanced functional connectivity properties of human brains during in-situ nature experience. PeerJ, 4, e2210.

Chiang, Y. C., Li, D., & Jane, H. A. (2017). Wild or tended nature? The effects of landscape location and vegetation density on physiological and psychological responses. Landscape and Urban Planning, 167, 72–83.

Chiesa, A., Calati, R., & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464.

Craig, C., Klein, M. I., Menon, C. V., & Rinaldo, S. B. (2015). Digital nature benefits typical individuals but not individuals with depressive symptoms. Ecopsychology, 7(2), 53–58.

Dadvand, P., Tischer, C., Estarlich, M., Llop, S., Dalmau-Bueno, A., López-Vicente, M., et al. (2017). Lifelong residential exposure to green space and attention: A population-based prospective study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(9), 097016.

Emfield, A. G., & Neider, M. B. (2014). Evaluating visual and auditory contributions to the cognitive restoration effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 548.

Evensen, K. H., Raanaas, R. K., Hagerhall, C. M., Johansson, M., & Patil, G. G. (2015). Restorative elements at the computer workstation: A comparison of live plants and inanimate objects with and without window view. Environment and Behavior, 47(3), 288–303.

Faber, L. G., Maurits, N. M., & Lorist, M. M. (2012). Mental fatigue affects visual selective attention. PLoS One, 7(10), e48073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048073

Fuegen, K., & Breitenbecher, K. H. (2018). Walking and being outdoors in nature increase positive affect and energy. Ecopsychology, 10(1), 14–25.

Fuller, R. A., Irvine, K. N., Devine-Wright, P., Warren, P. H., & Gaston, K. J. (2007). Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biology Letters, 3(4), 390–394.

Gamble, K. R., Howard Jr., J. H., & Howard, D. V. (2014). Not just scenery: Viewing nature pictures improves executive attention in older adults. Experimental Aging Research, 40(5), 513–530.

Haga, A., Halin, N., Holmgren, M., & Sörqvist, P. (2016). Psychological restoration can depend on stimulus-source attribution: A challenge for the evolutionary account? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1831.

Han, K. T. (2017). The effect of nature and physical activity on emotions and attention while engaging in green exercise. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 24, 5–13.

Hartig, T., Mang, M., & Evans, G. W. (1991). Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environment and Behavior, 23(1), 3–26.

Irvine, K. N., & Kaplan, S. (2001). Coping with change: The small experiment as a strategic approach to environmental sustainability. Environmental Management, 28(6), 713–725.

Jackson, M. (2008). Distracted: Reclaiming our focus in a world of lost attention. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

James, W. (1890). Attention. In The principles of psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 402–458).

James, W. (1892). Psychology: Briefer course. New York: Henry Holt & Co.

Jha, A. P., Denkova, E., Zanesco, A. P., Witkin, J. E., Rooks, J., & Rogers, S. L. (2019). Does mindfulness training help working memory ‘work’ better? Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 273–278.

Jiang, B., Schmillen, R., & Sullivan, W. C. (2019). How to waste a break: Using portable electronic devices substantially counteracts attention enhancement effects of green spaces. Environment and Behavior, 51(9–10), 1133–1160.

Joye, Y., Pals, R., Steg, L., & Evans, B. L. (2013). New methods for assessing the fascinating nature of nature experiences. PLoS One, 8(7), e65332.

Jung, M., Jonides, J., Northouse, L., Berman, M. G., Koelling, T. M., & Pressler, S. J. (2017). Randomized crossover study of the natural restorative environment intervention to improve attention and mood in heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 32(5), 464–479.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182.

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., & Ryan, R. (1998). With people in mind: Design and management of everyday nature. Island Press, Washington DC.

Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (2003). Health, supportive environments, and the Reasonable Person Model. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), p. 1484–1489.

Kaplan, S., & Berman, M. G. (2010). Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(1), 43–57.

Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1989 [1982]). Cognition and environment: Functioning in an uncertain world. Ann Arbor, MI: Republished by Ulrich’s.

Katsuki, F., & Constantinidis, C. (2014). Bottom-up and top-down attention: Different processes and overlapping neural systems. The Neuroscientist, 20(5), 509–521.

Kim, J., Cha, S. H., Koo, C., & Tang, S. K. (2018). The effects of indoor plants and artificial windows in an underground environment. Building and Environment, 138, 53–62.

Korpela, K. M., Ylén, M., Tyrväinen, L., & Silvennoinen, H. (2008). Determinants of restorative experiences in everyday favorite places. Health & Place, 14(4), 636–652.

Kuo, M., Browning, M. H., & Penner, M. L. (2018). Do lessons in nature boost subsequent classroom engagement? Refueling students in flight. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2253.

Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2001). Aggression and violence in the inner city: Effects of environment via mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior, 33(4), 543–571.

Kuo, F. E., & Taylor, A. F. (2004). A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health, 94(9), 1580–1586.

Largo-Wight, E., Guardino, C., Wludyka, P. S., Hall, K. W., Wight, J. T., & Merten, J. W. (2018). Nature contact at school: The impact of an outdoor classroom on children’s well-being. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 28(6), 653–666.

Lee, K. E., Sargent, L. D., Williams, N. S., & Williams, K. J. (2018). Linking green micro-breaks with mood and performance: Mediating roles of coherence and effort. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 60, 81–88.

Lee, K. E., Williams, K. J., Sargent, L. D., Williams, N. S., & Johnson, K. A. (2015). 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 182–189.

Levy, D. M., Wobbrock, J. O., Kaszniak, A. W., & Ostergren, M. (2011, May). Initial results from a study of the effects of meditation on multitasking performance. In CHI’11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM.

Lindland, E., Fond, M., Haydon, A., & Kendall-Taylor, N. (2015). Nature doesn’t pay my bills: Mapping the gaps between expert and public understandings of urban nature and health. Frameworks Institute, Washington, DC.

Li, D., & Sullivan, W. C. (2016). Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landscape and Urban Planning, 148, 149–158.

Lin, Y. H., Tsai, C. C., Sullivan, W. C., Chang, P. J., & Chang, C. Y. (2014). Does awareness effect the restorative function and perception of street trees? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 906.

Lymeus, F., Lindberg, P., & Hartig, T. (2018). Building mindfulness bottom-up: Meditation in natural settings supports open monitoring and attention restoration. Consciousness and Cognition, 59, 40–56.

Matsuoka, R. H. (2010). Student performance and high school landscapes: Examining the links. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97(4), 273–282.

Miles, I., Sullivan, W. C., & Kuo, F. E. (1998). Ecological restoration volunteers: The benefits of participation. Urban Ecosystem, 2(1), 27–41.

Ohly, H., White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Bethel, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Nikolaou, V., et al. (2016). Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B, 19(7), 305–343.

Pasanen, T. P., Johnson, K. A., Lee, K. E., & Korpela, K. M. (2018). Can nature walks with psychological tasks improve mood, self-reported restoration, and sustained attention? Results from two experimental field studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2057.

Poon, K. T., Teng, F., Wong, W. Y., & Chen, Z. (2016). When nature heals: Nature exposure moderates the relationship between ostracism and aggression. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 159–168.

Raanaas, R. K., Evensen, K. H., Rich, D., Sjøstrøm, G., & Patil, G. (2011). Benefits of indoor plants on attention capacity in an office setting. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(1), 99–105.

Roe, J., & Aspinall, P. (2011). The restorative benefits of walking in urban and rural settings in adults with good and poor mental health. Health & Place, 17(1), 103–113.

Rogerson, M., & Barton, J. (2015). Effects of the visual exercise environments on cognitive directed attention, energy expenditure and perceived exertion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(7), 7321–7336.

Rogerson, M., Gladwell, V., Gallagher, D., & Barton, J. (2016). Influences of green outdoors versus indoors environmental settings on psychological and social outcomes of controlled exercise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(4), 363.

Sahlin, E., Lindegård, A., Hadzibajramovic, E., Grahn, P., Vega Matuszczyk, J., & Ahlborg Jr., G. (2016). The influence of the environment on directed attention, blood pressure and heart rate—An experimental study using a relaxation intervention. Landscape Research, 41(1), 7–25.

Schutte, A. R., Torquati, J. C., & Beattie, H. L. (2017). Impact of urban nature on executive functioning in early and middle childhood. Environment and Behavior, 49(1), 3–30.

Shin, W. S., Shin, C. S., Yeoun, P. S., & Kim, J. J. (2011). The influence of interaction with forest on cognitive function. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 26(6), 595–598.

Sonntag-Öström, E., Nordin, M., Lundell, Y., Dolling, A., Wiklund, U., Karlsson, M., et al. (2014). Restorative effects of visits to urban and forest environments in patients with exhaustion disorder. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13(2), 344–354.

Sood, A., & Jones, D. T. (2013). On mind wandering, attention, brain networks, and meditation. Explore (NY), 9(3), 136–141.

Stevenson, M. P., Schilhab, T., & Bentsen, P. (2018). Attention Restoration Theory II: A systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B, 21(4), 227–268.

Sullivan, W. C., & Chang, C. Y. (2011). Mental health and the built environment. In A. L. Dannenberg, H. Frumkin, & R. J. Jackson (Eds.), Making healthy places: Designing and building for health, well-being, and sustainability (pp. 106–116). Washington, DC: Island Press.

Sullivan, W. C., & Kaplan, R. (2016). Nature! Small steps that can make a big difference. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(2), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715623664

Szolosi, A. M., Watson, J. M., & Ruddell, E. J. (2014). The benefits of mystery in nature on attention: Assessing the impacts of presentation duration. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1360.

Tanaka, M., Yamada, H., Nakamura, T., Ishii, A., & Watanabe, Y. (2013). Fatigue-recovering effect of a house designed with open space. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 9(2), 82–86.

Taylor, A. F., & Kuo, F. E. (2009). Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12(5), 402–409.

Taylor, A. F., Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2001). Coping with ADD: The surprising connection to green play settings. Environment and Behavior, 33(1), 54–77.

Ulset, V., Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., Bekkhus, M., & Borge, A. I. (2017). Time spent outdoors during preschool: Links with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 52, 69–80.

Valtchanov, D., & Ellard, C. G. (2015). Cognitive and affective responses to natural scenes: Effects of low level visual properties on preference, cognitive load and eye-movements. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 184–195.

Van der Jagt, A. P., Craig, T., Brewer, M. J., & Pearson, D. G. (2017). A view not to be missed: Salient scene content interferes with cognitive restoration. PLoS One, 12(7), e0169997.

Van Dijk-Wesselius, J. E., Maas, J., Hovinga, D., Van Vugt, M. V. D. B. A., & Van den Berg, A. E. (2018). The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: A prospective intervention study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 180, 15–26.

Van Praag, C. D. G., Garfinkel, S. N., Sparasci, O., Mees, A., Philippides, A. O., Ware, M., et al. (2017). Mind-wandering and alterations to default mode network connectivity when listening to naturalistic versus artificial sounds. Scientific Reports, 7, 45273.

Wallner, P., Kundi, M., Arnberger, A., Eder, R., Allex, B., Weitensfelder, L., et al. (2018). Reloading pupils’ batteries: Impact of green spaces on cognition and wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1205.

Wang, X., Rodiek, S., Wu, C., Chen, Y., & Li, Y. (2016). Stress recovery and restorative effects of viewing different urban park scenes in Shanghai, China. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 15, 112–122.

Wells, N. M. (2000). At home with nature: Effects of “greenness” on children’s cognitive functioning. Environment and Behavior, 32(6), 775–795.

Weng, P. Y., & Chiang, Y. C. (2014). Psychological restoration through indoor and outdoor leisure activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(2), 203–217.

Wilkie, S., & Clouston, L. (2015). Environment preference and environment type congruence: Effects on perceived restoration potential and restoration outcomes. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(2), 368–376.

Wu, C. D., McNeely, E., Cedeño-Laurent, J. G., Pan, W. C., Adamkiewicz, G., Dominici, F., et al. (2014). Linking student performance in Massachusetts elementary schools with the “greenness” of school surroundings using remote sensing. PLoS One, 9(10), e108548.

Yin, J., Zhu, S., MacNaughton, P., Allen, J. G., & Spengler, J. D. (2018). Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment. Building and Environment, 132, 255–262.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sullivan, W.C., Li, D. (2021). Nature and Attention. In: Schutte, A.R., Torquati, J.C., Stevens, J.R. (eds) Nature and Psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, vol 67. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69020-5_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69020-5_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-69019-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-69020-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)