Abstract

Nowadays, “internationalisation” is a topic of concern for many types of research on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). SMEs pursue internationalization policy as a leading process to keep and improve their position in the competitive business markets. However, SMEs face many challenges that hinder the successful implementation of the internationalization process. This chapter aims to recognise the important barriers to internationalisation for Iranian SMEs. We conduct two studies using a combined exploratory and confirmatory approach. We apply the Delphi method for exploring and forecasting the key barriers in the first study. In the second study, we validate the key indicator employing a Structural Equation Modelling technique for the Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the survey data. In the Delphi method, a group of 24 managers and academic professors in Iran, identified the main barriers. A sample of 210 survey observations was collected from the owner and top managers, senior managers, and employees. The results suggest 8 key factors and 31 indicators of barriers to internationalisation associated with Iranian SMEs: informational, financial, marketing, functional, procedural, governmental, environmental and, tariff and non-tariff. This research contributes to the knowledge of critical obstacles concern for current and future business internationalisation, and the outcomes provide practical implications.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In recent years, the importance of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in industrialised countries, especially in developing countries, has been increasing. The emergence of new technologies in production and communication has led to fundamental revisions in improving production capacity, improving production methods and distributing and changing the organisational structure of firms, which has generally increased the importance of SMEs (Ng and Kee 2012). Moreover, the reform in the business environment also has a significant impact on all aspects of trade and production. These changes have made a new condition in which the role of SMEs in increasing economic scales and, consequently, improving sustainable development has become more brilliant (Cressy and Olofsson 1997; Cassar and Holmes 2003; Saarani and Shahadan 2013).

Parallel with these major changes, globalisation and its consequences have forced SMEs to pay more attention to their business domain for expanding economics and commercials operations beyond national borders (Jafari-Sadeghi et al. 2019, 2020). As SMEs in many developing countries have started to operate in international markets and extended their presence in the markets of developed countries, therefore, it seems it is not only an optional promotion but also is a mandatory factor so that some international enterprises, such as the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), recognise integration into the global economy through an open economy and democracy as the best way to overcome poverty and inequality in developing countries; therefore, development of the private sector, especially SMEs, is fundamental for achieving these goals (Soto 2015). The report published by the European Commission (2007) indicates the increase in average global trade by 6% since 1990, which is faster than the global gross domestic product (GDP) (Dana et al. 2011; Hope et al. 2019). In the same way, some new challenges such as open economy, shrinking government and privatisation of more specialised professions, increased competitive pressure and reduced direct assistance and government support (Ferraris et al. 2020), particularly in developing countries, have also changed the corporate sales and marketing policies (Dana et al. 2004; Sukumar et al. 2020). Companies have realised the need to offer newer products and expand into wider markets to maintain survival as well as grow more in a complex business environment (Laudal 2011). As a result, the need for internationalisation among SMEs has become more pronounced. Expanding export activities helps companies in increasing profitability and improving trade balances directly and indirectly helps society deal with the problems of poverty and unemployment (Fliess and Busquets 2006; Karadeniz and Göçer 2007; Sadeghi et al. 2019).

Nowadays, many companies are encouraged by governments to consider internationalisation in their medium- and long-term strategies (Al-Hyari et al. 2012; Hajiagha et al. 2013, 2015, 2018). In addition to the inherent inclination of companies themselves, many researchers have studied this issue from different dimensions, and internationalisation has been the subject of much research in the study of corporate strategy, international trade and entrepreneurship (Fliess and Busquets 2006; Al-Hyari et al. 2012; Jafari-Sadeghi et al. 2020). Along with the expansion of long-term horizons and the entry and involvement of companies in international trade, various problems and obstacles in the path of internationalisation became apparent, and researchers, from different scopes, have examined the background and causes of barriers, which has led to the identification of factors limiting the spread of internationalisation (Dana 2001). These restrictions which limit the ability to initiate, develop and sustain business abroad are caused by a wide range of attitudinal, structural and operational factors. Several restrictions in internationalisation are related to the liability of foreignness and newness (Dana 2001). The challenges become more apparent when target markets have fewer intrinsic features similar to the local market (Lange et al. 2000; Korsakiene 2015). Therefore, companies need new resources to enable them to enter foreign markets. The problem of adapting to international markets seems more acute for SMEs because the problem of providing new resources (and especially financial resources) for these companies is bigger than large companies (Fliess and Busquets 2006; Sox et al. 2014).

In this study, we have tried to consider the significant barriers and problems in the path of internationalisation of SMEs, and by collecting experts’ opinions and experiences, we identified a road map for decision-makers in government and SMEs managers.

2 Literature Review

The experience of many developing and developed countries shows that the SME sector plays a pivotal role in economic and industrial development for various reasons (Sadeghi and Biancone 2018; Dabić et al. 2020). SMEs, as the backbone of the economy, are important to almost every economy in the world, especially for developing countries. According to the European Commission in 2008, the number of SMEs operating within the EU reached 60 million businesses, which accounted for 99.8% of all enterprises. In East Asia, the figure is estimated at 20–30 million businesses, accounting for about 95% of all businesses in the region (Demary et al. 2016; Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary 2018). Therefore, SMEs are rapidly becoming major players in global markets, and their role will grow if technological and legal barriers are removed and protectionist policies are increased. Shifting the trade and investing scopes from a limited domestic to global makes new opportunities for SMEs (Senik et al. 2010; Dana and Ramadani 2015; Ratten et al. 2017). Therefore, SMEs have realised the importance of “international business” as the most effective way to increase their commercial activities outside the borders of domestic markets. This exchange process can be done through the export or import of goods, services and technology. As a result, “internationalisation” entered the corporate business literature as the mainstay of the business (Angulo-Ruiz et al. 2020).

In business literature, there are many definitions for internationalisation. According to some definitions, internationalisation is considered as the geographical development of corporate economic activities beyond national borders (Bardhan 2002; Beheshti et al. 2016; Farooqi and Miog 2012). Some researchers defined internationalisation as a process that seeks to describe a company’s efforts to expand its economic operations outside the domestic sphere (Labate and Jungaberle 2011; Bang 2013). These common features have led to the internationalisation of companies as a step-by-step process or as a regular and evolutionary process that takes place with increasing international participation and relevant organisational changes (Dana 2004). Meanwhile, some researchers have not accepted these restrictions in the definition of internationalisation to the physical expansion of the company’s scope of activity and consider this concept beyond the geographical concept. Welch and Luostarinen (1988) consider internationalisation as a “process of increasing participation in international activities” (Chong et al. 2019; Dabić et al. 2020). By this definition, they emphasise that a company may be involved in international activities, but there is no avoidance for these activities to continue because internationalisation can occur at any stage of the firm’s development. Internationalisation is a process in which enterprises both increase their awareness of the direct and indirect effects of international exchanges in their future and establish their exchanges with other countries (Paul et al. 2017; Paul 2020). In some studies, internationalisation is reflected as “the process of adapting corporate processes to international environments” (Sadeghi et al. 2018; Saridakis et al. 2019; Schmid and Morschett 2020). Hollensen (2007) considers “doing business in many countries” to be an important principle of the definition of internationalisation (Harris and Wheeler 2005; Kreutzer et al. 2017; Bowen 2019). Internationalisation is defined as the “process of developing trade relations networks in other countries through expansion, influence, and integration” (Coviello and Munro 1997; Coviello and Martin 1999; Zain and Ng 2006). The focus in this definition is on relationships and connections. Relationships can help companies enter foreign market networks. According to Vahlne and Johanson (2017), connections are an important principle for networking and entering into internationalisation. Mejri and Umemoto (2010) know internationalisation as expanding the company’s business operations to foreign markets, which will not necessarily constitute a one-dimensional process (Ribau et al. 2018; Mahmoudi et al. 2019). From an entrepreneurial perspective, Oviatt and McDougall (2005) see internationalisation as the process of discovering, approving, evaluating and exploiting opportunities across borders to build goods and services (Oviatt and McDougall 2005; Coviello et al. 2011).

Internationalisation is found to be an important aspect of the maximisation of business opportunities, and over the last few decades, many SMEs began internationalisation as a requirement for business success (Ratten et al. 2007; Rundh 2007). Internationalisation is a significant description of the outward movement of the international operations of a firm and wildly is applied in international business studies (Ratten et al. 2017). In most studies, internationalisation has been viewed as outward processes that are related to exporting, licensing, franchising and foreign direct investment (Karlsen et al. 2003; Welch and Paavilainen-Mäntymäki 2014).

Considering the advantages of internationalisation is also an important issue for SMEs. SMEs seek to internationalise their business for greater economic and financial benefits, but the practical incentives that motivate them to pursue this process are different (Chiao et al. 2006; Kumar 2008; Landau et al. 2016). Cost is the most important motivation for manufacturers to expand their business and internationalise. Managers of production companies and manufacturers are encouraged to expand their business to enhance competitiveness versus commercial competitors and manufacturers in the market (Mahdiraji et al. 2011, 2019, 2020). Thus, accessing lower labour cost can be a reasonable driver for them. However, for service firms, the prime driver is achieving new knowledge and technology (Doh et al. 2010; Abdul-Aziz et al. 2013). Although it should be noted that market share is also an important driver for firms. When a company feels its business share in the market is decreasing, its knowledge on the domestic markets is not adequate (e.g. Dezi et al. 2019) and the cost of the manufacturing process is increasing, internationalisation can be a good opportunity for expanding the market, accessing new knowledge and finding cheaper material and working labour (Ratten et al. 2007; Paul et al. 2017). These stimuli can also be effective for service companies, but the “time” is more attractive for them than manufacturing firms. Time zone differences enable service providers (SPs) to provide around the clock service. The nonstop operation helps SPs to enjoy benefits of cost reduction and eliminate the role of “time” to market access, in other words, have their customers at all times (Mokhtarzadeh et al. 2018).

However, sometimes, companies do not succeed in internationalisation and may not reach their predicted plans and the expected outcome of the internationalisation because they cannot overcome the barriers faced in the processes (Shaw and Darroch 2004; Rahman et al. 2017). Barriers to internationalisation have been a favourite subject in the context of exporting activities as in an extreme body of study, researchers focused on its causes and effects in both conceptual and empirical approaches (Ghauri et al. 2003; Leonidou and Theodosiou 2004; Leonidou et al. 2011). These barriers, in business literature, are known as restrictions that affect and disturb the firm’s capability to start, develop or uphold business operations in overseas markets. Leonidou (2004) defined barriers as the limitations that hinder a firm’s ability to initiate, develop or sustain business operations in overseas markets.

Some scholars tried to elaborate on the barrier-related differences for a wide range of firms (Pinho and Martins 2010; Leonidou et al. 2011; Kahiya 2013; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019). For some firms (that are known domestic firms), the barriers are more related to the management’s desire to not change the current business domain that is rooted of their limited communication with the foreign market, lack of sufficient knowledge of exporting procedures, lack of qualified personnel for conducting exports and an intrinsic fear of overseas product acceptance and raising initial investment (Pinho and Martins 2010). However, for internationalised firms, the barriers are different. These firms have more challenges with export procedures, slow payment by foreign buyers, poor economic conditions in foreign markets, etc. that are more operational barriers and relate to market variables (Leonidou 2004; Taghavifard et al. 2018). Despite these differences in obstacles to internationalisation, there are many common challenges which affect companies in the internationalisation process, and given the importance of this issue, identifying and investigating their effects have always been a favourite to researchers. Different classifications have been proposed to categorise different barriers based on their different characteristics. For instance, in some of the literature, barriers are divided into two groups: initial problems which are linked to shortage of experience and knowledge and ongoing problems that are related to greater participation in foreign markets (Bilkey and Tesar 1977; Chong et al. 2019; Dabić et al. 2020; Morais and Ferreira 2020; Treviño and Doh 2020). Some researchers have divided the challenges of internationalisation into two groups: internal and external challenges. Depending on whether the company can control the problems in internationalisation directly or not, barriers are also divided into two main parts: controllable and uncontrollable factors (Buckley 1993; Kahiya 2013; Chandra et al. 2020a; Mueller-Using et al. 2020). Controllable factors, most of which are internal barriers, are related to internal organisational resources and capabilities, including goods and services policies, sales, pricing and distribution plans that are directly under the control and planning of the management of the enterprise. They can formulate and implement legal restrictions, consumer tastes and strategies based on new conditions in international markets and their competitive challenge. Uncontrollable factors are known as external factors, depending on the specific market conditions, the external environment of the company which includes the general policies of the government and especially marketing activities by competitors overseas, the legal structure and internal economic conditions of the country, political and economic situation, technology level, geography and culture (Donthu and Kim 1993; Shoham and Albaum 1995; Leonidou and Theodosiou 2004; Goswami and Agrawal 2019).

According to Cavusgil and Nevin (1981), the real barrier for internationalisation for SMEs is internal barriers (Coudounaris 2018), but Gripsrud and Benito (2005) believed in external barriers. Some researchers studied barriers to internationalisation as both aspects, internal and external obstacles (Tesfom and Lutz 2006; Pinho and Martins 2010; Al-Hyari et al. 2012; Uner et al. 2013; Roy et al. 2016a). Classification of internal and external types of barriers has also been done by many researchers. According to Leonidou (2004), internal barriers consist of functional, informational and marketing, and external barriers are classified as to procedural, governmental, task and environmental. Arteaga-Ortiz and Fernández-Ortiz (2010) believed barriers can be categorised into four groups: knowledge, resource, procedure and exogenous. Al-Hyari et al. (2012) studied the barriers to internationalisation in Jordanian SMEs, in four categories, informational and financial as internal barriers and environmental and governmental as external. However, in many studies on this subject, internal barriers have been classified more into four groups, informational, financial, marketing and functional, and external barriers have come more in the form of procedural, governmental, environmental and tariff and non-tariff barriers (Muhammad Azam Roomi and Parrott 2008; Hutchinson et al. 2009; Kahiya 2013; Roy et al. 2016b; Pavlák 2018).

In this study, we examined internal barriers as informational, financial, marketing and functional obstacle and external barriers in procedural, governmental, environmental and tariff and non-tariff barriers to examine a wider range of barriers to internationalisation.

3 Methodology

This study is a developmental research based on a systematic approach to designing, developing and evaluating instructional processes. It is also considered applied research because of addressing the issue of barriers to internationalisation. Also, we applied a descriptive research method that consists of a set of methods designed to describe the conditions or phenomena in a study. So, we identified the dimension and barrier indicators through a Delphi survey, and then we analysed the “barriers of internationalization” by using the structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis—to examine the construct validity of factors.

3.1 Delphi Method

Delphi method is a systematic approach or method of research to extract opinions from a group of experts on a topic or a question or to reach a group consensus through a series of questionnaire rounds while maintaining the anonymity of the respondents and feedback: comments to panel members (Toma and Picioreanu 2016). Delphi is a process which makes use of professional judgments from heterogeneous and independent experts on a specific topic at a large geographical level using questionnaires that are repeated continuously until a consensus is reached. Delphi is a multi-step study method for gathering opinions on the subjectivity of the subject and using written answers instead of bringing together a group of experts; the goal of the consensus is to be able to freely express and revise ideas with numerical estimates (Linstone and Turoff 1975). Delphi’s main goal was to predict the future, but it is also used in decision-making, increasing effectiveness, judgment, facilitating problem-solving, needs assessment, goal setting, planning assistance and prioritisation. In the Delphi method, the repetition or iteration of the questionnaire, the expert group, controlled feedback, anonymity, analysis of results, consensus, time and the coordinating team are the main components. According to Gordon (1994), Delphi is a useful communication tool between a group of experts that facilitates the formulation of group members’ opinions. Delphi is a way of organising a group communication process so that it enables all members of the group to effectively tackle a complex problem (Toma and Picioreanu 2016). Hsu and Sandford (2007), in their article on the Delphi method, believe this method can be conducted in three or four rounds based on previous successful research using Delphi (Hjarnø et al. 2007; Hsu and Sandford 2007; Steurer 2011).

3.2 The Panel of Experts

Delphi participants are experts or panellists. They need four characteristics: knowledge and experience in the subject, willingness, sufficient time to participate and effective communication skills, and the key parameters of the study are the competence of the panellists, the size of the panel and the method of their selection. This method is based on finding and gathering experts’ opinions in a short term; therefore, final results depend on the expertise of the individuals, the quality and accuracy of the responses and their ongoing involvement and participation during the study period (Steurer 2011). The Delphi panel of experts should have sufficient knowledge and mastery of the subject matter, be involved in the discussion and influence each step of the process outcome. Respondents should be relatively neutral, and the information gained reflects their knowledge and understanding. In addition to the participants’ ability, interest and commitment to the subject, continuous involvement in all rounds is also required. We applied the judgmental method and snowball sampling method as a non-probability sampling method to identify the panel members (Etikan and Bala 2017). Therefore, in a preliminarily step, a shortlist of professional investigators and managers was prepared, and then they completed this panel by introducing and adding more members which are known as experts. Therefore, 24 members were selected. Table 1 shows the panel member composition.

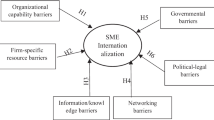

As a pre-start activity, which involves developing a research question and a pretest for the appropriateness of words such as ambiguity, the pilot should be conducted outside of the research process and to identify ambiguities and estimate time; of course, researchers may pretest or pilot the questionnaire at the beginning or at each stage to keep the questions clear and focus on the purpose of the research. To identify the barriers, a detailed study was conducted in the research literature to extract important concepts and variables which is finally applied in the Delphi questionnaire. For example, panellists were asked: “To what extent do you agree or disagree that lack of financial resources is a barrier for internationalisation?” A 5-point Likert scale was used for the measure. The questionnaire, also, consisted of open-ended questions that asked participants to improve the questionnaire if they thought the factor or other concepts might have ethical challenges but were not mentioned in the questionnaire; as such, participants were asked: “Please provide other indicators relevant to the barrier of internationalisation.” After collecting the first-round questionnaires, the scores of each of the variables of the questionnaire were determined, and their mean, standard deviation and Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) were calculated. For each round, the results of the previous round are analysed and the variables that have an average of less than 3 removed and the other variables presented to the participant in the next round questionnaire. In the second round, the respondents also were informed about the group feedback in the first round and the migraine responses individually. In the third round, this trend was repeated, and finally, by expert consensus, 31 variables were obtained. Diagram 1 illustrates the steps of the Delphi method (Fig. 1).

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for three rounds of Delphi synthesis (M > 3). This analysis has been done by SPSS software. The important issue in the study of the consensus in the Delphi method is the central tendency measures (such as means and standard deviation) in the descriptive statistics because low variation in consecutive rounds is called success.

After three rounds of the research process and based on the results, it was proved that there was a good consensus among the members, and thus the repetition of the rounds ended. In almost all factors, the proportion of members who ranked the order of importance of the challenges according to the group, as a whole, was more than 50%, and the standard deviation of members’ responses to the importance of success factors in the third round was lower than in the first and second rounds. As mentioned, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) also indicates the extent of the members’ collective agreement on the factors. Kendall’s W ranges between “0” reflecting “no agreement” and “1” indicating the “complete agreement”. After three rounds of research, this coefficient has increased to an optimal figure of 0.6, which confirms that agreement on the degree of importance of ethical challenges has been increased and reached to 60% between experts and panellists (Table 3).

3.3 Factor Analysis

After identifying the most important ethical challenges arising from the use of digital technologies in the health sector, the correlation coefficients of the variables are tested. Consequently, the results of the Delphi technique were provided as a second questionnaire to the interviewers in the second statistical sample. The second statistical community includes a wide range of decision-makers in business such as owners and top managers of export manufacturing companies, senior business managers related to the commercial activities and senior employees of marketing, sales and business departments of companies involved in international business activities. Based on the Cochran formula, for the population at the error level of 0.05, we determined the appropriate sample size on n = 200 members. Therefore, 380 questionnaires, which were set up by Likert Scales, were distributed, and finally, by considering all received responses, 212 questionnaires were accepted, which reflects over 60 per cent response rate (Table 4). For the next step, we determined the reliability of the questionnaire by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Therefore, in a pretesting of 54 questionnaires, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.902 that indicates the method employed has an acceptable level of confidence.

3.4 Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Conceptual Model of Research

After identifying the most significant barriers to internationalisation, we applied the Factor analysis to recognise and detect factors. By factor analysis, variables are classified into two factors at least. According to this method, each factor can be considered as a hypothetical variable combining several variables that have similarities in appearance (Rezaei et al. 2020). The factor analysis method facilitates analysing by data reduction and detects structure by measuring the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. In other words, the research variables are restricted by two or more categories based on their common characteristics, and these categories are called factors, and the relationships between the factors are obtained; in each factor, the relations between its variables are calculated, and ultimately the main objective of the research, which is the relationship between the variables of the research, is calculated. For measuring the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, factor analysis identifies whether the items are placed inside the factors (Bandalos and Finney 2018).

Factor analysis approaches can be divided into two general categories: exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In this study since we have already determined the structure of the factors, therefore, the CFA analysis is used (Sadeghi and Biancone 2018). The most important goal of confirmatory factor analysis is to determine the adaptability of the predefined conceptual model with a set of observed data. In other words, confirmatory factor analysis seeks to determine whether the number of measured variable loads on these factors corresponds to what was expected based on the theoretical model.

3.5 Goodness of Fit

In a general description, by the goodness of fit, the researcher can find how well its model fits a set of observations. These measures typically indicate the discrepancy between observed values and the values expected under the designed model in the survey (Marsh et al. 2005). It should be noted that there is no general agreement about these tests and several indicators are used to measure model fit. Usually, three to five indices are sufficient to confirm the model. Some of the goodness of fit indexes are the chi-square test (x 2/df), the goodness of fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Mulaik et al. 1989). However, the two most prominent indices that are visible in the LISREL output are the chi-square test (x 2/df) and the RMSEA.

3.6 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To confirm the validity of the questionnaire and the structure and to measure barriers, second-order confirmatory factor analysis has been implemented, and, as mentioned, to measure these 8 factors, 31 items are considered. Table 5 shows the second-order confirmatory factor analysis, while Table 6 presents the fitness indices.

According to Table 5, since the path coefficient and t values for all factors exceed at the level of p < 0.05, it is found the correlations are significant (p < 0.05) and positive.

4 Results and Discussion

The CFA outputs show that among the factors of this test, the most important obstacle for the internationalisation of Iranian SMEs is the financial factor (Cronbach’s alpha 95%). The second obstacle was marketing-related issues, and informational and environmental are in the next category by R2 = 0.81. The results also demonstrate the procedural and tariff and non-tariff are not as important as the other barriers are in internationalisation for SMEs. Despite the increasing role of SMEs in globalisation, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) statistics show a slowdown in internationalisation in developing countries (Jafari-Sadeghi et al. 2020). This downward trend indicates a lack of courage in SMEs to enter international markets. As a result, exploring the reasons and obstacles to the internationalisation of companies has been a fascinating topic for researchers. Informational, financial, marketing, functional, governmental, environmental and tariff and non-tariff are some of the main barriers which reduce the firm’s desire to internationalise.

Concerning external-related barriers, in general, the results show internal-related barriers are a more considerable issue for experts as their average of the coefficient is higher than external barriers. According to the resource-based theory, the resources are the key factors for firms in expanding their market into a foreign market. One of these essential resources is financial resources. According to the findings, financial barriers are identified as a significant barrier to SMEs internationalisation by 0.81. This barrier is recognised in financing resources, working capital and insurance cost for internationalisation. Financing is a common considerable issue for SMEs for many centuries. SMEs are faced with this problem from starting out up to growing their business. As the major sources of financing sectors, banks are reluctant to invest in companies due to the lack of adequate collateral and the uncertainty of debt repayment. Besides, the regional and global economic crises impact corporate investment negatively (Arndt et al. 2009). Our findings are consistent with the results of Camra-Fierro et al. (2012); Chandra et al. (2020b); and Rahman et al. (2017). Marketing is another key factor that can hinder the implementation of the international process. Globalisation and international marketplaces have made it easier for everyone to access international markets which simply means companies’ competitions have become closer (Dana et al. 1999). Therefore, they should improve the quality of their products while providing a more reasonable price. In parallel with the product cost, they also should find the cheapest distribution ways to reduce their overhead expenses. Difficulty in developing new products, lack of competitive price in a foreign market, problems in goods distribution and representation and high transport cast in and to foreign markets are some issues that compose marketing barrier. Our findings are in line with some previous studies (Raymond et al. 2001; Rutashobya et al. 2005; Singh et al. 2010; Roy et al. 2016b). Information is perhaps the most crucial device for firms in internationalisation. Informational barriers, which are categorised as an internal challenge, refer to those problems that are rooted in lack or insufficient information, knowledge and data for analysing and identifying foreign market and customers. According to some studies of barriers to internationalisation, the information plays a vital role in the success or failure of companies on the path to internationalisation (Su¡rez-Ortega 2003; Pinho and Martins 2010; Kahiya 2018; Felzensztein et al. 2019). Among the external challenges of internationalisation, environmental factors have the highest correlation. Environmental barriers refer to macroeconomic, political, cultural, social and financial constraints that exist regardless of the inherent company’s ability for internationalisation which included international sanctions, poor economic conditions abroad, currency fluctuations and cultural and linguistic differences. Environmental problems such as economic and political instability and the global imposed limitation are the major risk for export and international trade for SMEs. In studies which are conducted by Camra-Fierro et al. (2012) and Al-Hyari et al. (2012), the political and economic uncertainty as an environmental issue is an important barrier for SMEs.

SMEs need significant government support to succeed in entering international markets, and the government’s lack of attention and incentives has been one of their main obstacles to internationalisation. Governmental barriers are associated with the action and inactions that arise from the economic decisions of home governments and their policies in internationalisation. These barriers are related to unfavourable and restriction rules and regulations. According to Ahmed et al. (2008); Al-Hyari et al. (2012); and Korsakiene (2015) which conducted their studies in Lebanon, Jordan and Lithuania, respectively, lack of government assistant causes a lot of problem for SMEs in internationalisation. It is also argued that the government complex bureaucracy has a positive impact on internationalising the SMEs (Freeman and Reid 2006).

Among internal barriers, the functional problem has the same correlation as governmental has in external barriers. This challenge is related to the insufficiencies of human resource management dealing with the internationalisation process (Boudlaie et al. 2020). Without allocating sufficient time, sources (e.g. expert employees) and energy, SMEs will face a lot of difficulties in their process into international markets. Our results are parallel with some research in considering SMEs’ barriers to internationalisation (e.g. Leonidou 2004; Green 2007; Shah et al. 2013; Narayanan 2015; George et al. 2019).

Procedural barriers are associated with the operational aspects of transactions with foreign customers. Internationalisation is affected by procedural challenges such as being unfamiliar with techniques and procedures, failure in communication and the problem about the slow collection of payments and difficulty in enforcing contracts which finally has a deep impact on export behaviour. Our result shows this barrier is not as important as internal challenges for Iranian SMEs. According to Uner et al. (2013), the procedural barrier is the most important barrier for Turkish SMEs. Roy et al. (2016b) found, for Indian SMEs, that the procedural barrier is the most important obstacle. Based on Mendy and Rahman’s (2019) study, legal procedural complexity is known as a factor in the path to internationalisation. Tariff and non-tariff barriers are associated with foreign government policies on exporting and internationalising. High tariff rate, inadequate property rights protection, restrictive rules in health and safety standards, arbitrary tariff classification and high costs of customs administration are some of tariff and non-tariff barriers which impose challenges in internationalisation process for SMEs (Shaw and Darroch 2004; Leonidou et al. 2011). Based on outputs, the Cronbach’s alpha for this relationship is the lowest among all analysed barriers.

5 Limitations

Interpretation of the findings and conclusions should be made in light of some limitations. Since the challenges for SMEs in internationalization have not been properly studied in Iran, we are limited to examining some parts of barriers which do not cover all aspects of the impact of obstacles on internationalisation. On the other hand, collecting data via the questionnaire has an inherent risk of common method bias. Participants may aim at consistency rather than accuracy, therefore introducing undue variance in the variables. Survivorship bias is another limitation for this research; our sample is limited; thus, by changing the sample size or society, the result may have different outputs. Furthermore, the scope of this research was limited to a two-step method to identify the barriers in internationalization procedures for SMEs. However, for such a complex challenge, we call for more research, which use practical cases to verify and enrich the outcome of this research. In this regard, by using a combined Delphi-CFA method in this research, the identified outcomes could predict the challenges in future studies in internationalization and demonstrate the significant role of each problem.

References

Abdul-Aziz A-R et al (2013) Internationalization of construction-related consultants: impact of age and size. J Prof Issues Eng Educ Pract. American Society of Civil Engineers 139(2):148–155

Ahmed ZU, Julian CC, Mahajar AJ (2008) Export barriers and firm internationalisation from an emerging market perspective. J Asia Bus Stud. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Al-Hyari K, Al-Weshah G, Alnsour M (2012) Barriers to internationalisation in SMEs: evidence from Jordan. Mark Intell Plan 30(2):188–211

Angulo-Ruiz F, Pergelova A, Dana LP (2020) The internationalization of social hybrid firms. J Bus Res. Elsevier 113:266–278

Arndt C, Buch CM, Mattes A (2009) Barriers to internationalization: firm-level evidence from Germany. IAW Diskussionspapiere

Arteaga‐Ortiz J, Fernández‐Ortiz R (2010) Why don’t we use the same export barrier measurement scale? An empirical analysis in small and medium‐sized enterprises. J Small Bus Manag 48(3):395–420

Bandalos DL, Finney SJ (2018) Factor analysis: exploratory and confirmatory. In: The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. Routledge, pp 110–134

Bang Y (2013) Internationalization of higher education: a case study of three Korean private universities. University of Southern California

Bardhan P (2002) Decentralization of governance and development. J Econ Perspect 16(4):185–205

Beheshti M, Mahdiraji HA, Zavadskas EK (2016) Strategy portfolio optimisation: a copras g-modm hybrid approach. Transform Bus Econ 15(3C):500–519

Bilkey WJ, Tesar G (1977) The export behavior of smaller-sized Wisconsin manufacturing firms. J Int Bus Stud. Springer 8(1):93–98

Boudlaie H, Mahdiraji HA, Shamsi S, Jafari-Sadeghi V, Garcia-Perez A (2020) Designing a human resource scorecard: an empirical stakeholder-based study with a company culture perspective. W. Kucharska (ed), p 113

Bowen R (2019) Motives to SME internationalisation. Cross Cult Strateg Manag. Emerald Publishing Limited

Buckley PJ (1993) Barriers to internationalization. In: Perspectives on strategic change. Springer, pp 79–106

Camra-Fierro J et al (2012) Barriers to internationalisation in SMEs: evidence from Jordan. Mark Intell Plan. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Cassar G, Holmes S (2003) Capital structure and financing of SMEs: Australian evidence. Acct Fin. Wiley Online Library 43(2):123–147

Cavusgil ST, Nevin JR (1981) Internal determinants of export marketing behavior: an empirical investigation. J Mark Res. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 18(1):114–119

Chandra A, Paul J, Chavan M (2020a) Internationalization barriers of SMEs from developing countries: a review and research agenda. Int J Entrep Behav Res. Emerald Publishing Limited

Chandra A, Paul J, Chavan M (2020b) Internationalization barriers of SMEs from developing countries: a review and research agenda. Int J Entrepreneurial Behav Res 26(6):1281–1310

Chiao Y-C, Yang K-P, Yu C-MJ (2006) Performance, internationalization, and firm-specific advantages of SMEs in a newly-industrialized economy. Small Bus Econ. Springer 26(5):475–492

Chong P et al (2019) Internationalisation and innovation on balanced scorecard (BSC) among Malaysian small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Manag Sci Lett 9(10):1617–1632

Coudounaris DN (2018) Typologies of internationalisation pathways of SMEs: what is new? Rev Int Bus Strateg. Emerald Publishing Limited

Coviello NE, Martin KA-M (1999) Internationalization of service SMEs: an integrated perspective from the engineering consulting sector. J Int Mark. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 7(4):42–66

Coviello N, Munro H (1997) Network relationships and the internationalisation process of small software firms. Int Bus Rev. Elsevier 6(4):361–386

Coviello NE, McDougall PP, Oviatt BM (2011) The emergence, advance and future of international entrepreneurship research—an introduction to the special forum. J Bus Ventur. Elsevier 26(6):625–631

Cressy R, Olofsson C (1997) European SME financing: an overview. Small Bus Econ. Springer 9(2):87–96

Dabić M et al (2020) Pathways of SME internationalization: a bibliometric and systematic review. Small Bus Econ. Springer 55(3):705–725

Dana LP (2001) Networks, internationalization & policy. Small Bus Econ. Springer 16(2):57–62

Dana LP (2004) Handbook of research on international entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing

Dana LP, Ramadani V (2015) Family business in transition economies: management, succession and internationalization

Dana L-P, Etemad H, Wright RW (1999) The impact of globalization on SMEs. Glob Focus 11(4):93–106

Dana L-P, Etemad H, Wright RW (2004) Back to the future: international entrepreneurship in the new economy. In: Emerging paradigms in international entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing, p 19

Dana L-P et al (2011) 32 internationalization of European entrepreneurs. In: World encyclopedia of entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing, p 274

Demary M, Hornik J, Watfe G (2016) SME financing in the EU: moving beyond one-size-fits-all. IW-Report

Dezi L, Ferraris A, Papa A, Vrontis D (2019) The role of external embeddedness and knowledge management as antecedents of ambidexterity and performances in Italian SMEs. IEEE Trans Eng Manag. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2019.2916378

Doh J et al (2010) Issues in services offshoring research: a multidisciplinary. Citeseer

Donthu N, Kim SH (1993) Implications of firm controllable factors on export growth. J Glob Mark. Taylor & Francis 7(1):47–64

Etikan I, Bala K (2017) Sampling and sampling methods. Biom Biostat Int J 5(6):149

Farooqi F, Miog R (2012) Influence of network forms on the internationalization process: a study on Swedish SMEs

Felzensztein C, Deans KR, Dana L (2019) Small firms in regional clusters: local networks and internationalization in the southern hemisphere. J Small Bus Manag. Taylor & Francis 57(2):496–516

Ferraris A, Santoro G, Pellicelli AC (2020) “Openness” of public governments in smart cities: removing the barriers for innovation and entrepreneurship. Int Entrep Manag J:1–22

Fliess B, Busquets C (2006) The role of trade barriers in SME internationalisation. OECD Pap 6(13):1–19

Freeman S, Reid I (2006) Constraints facing small western firms in transitional markets. Eur Bus Rev. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

George, A. D., Mathew, L. S. and Chandramohan, G. (2019) ‘Internationalization of SMEs: a Darwinian perspective’, in Transnational entrepreneurship. Springer, pp 363–378

Ghauri P, Lutz C, Tesfom G (2003) Using networks to solve export-marketing problems of small-and medium-sized firms from developing countries. Eur J Mark. MCB UP Ltd

Gordon, T. J. (1994) ‘The Delphi method’, Futures research methodology. American Council for the United Nations University: Washington, DC, 2(3), 1–30

Goswami AK, Agrawal RK (2019) Explicating the influence of shared goals and hope on knowledge sharing and knowledge creation in an emerging economic context. J Knowl Manag. Emerald Publishing Limited

Green, M. F. (2007) ‘Internationalizing community colleges: barriers and strategies’, New directions for community colleges. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company San Francisco, 2007(138), 15–24

Gripsrud G, Benito GRG (2005) Internationalization in retailing: modeling the pattern of foreign market entry. J Bus Res. Elsevier 58(12):1672–1680

Hajiagha SHR, Mahdiraji HA, Hashemi SS (2013) Multi-objective linear programming with interval coefficients. Kybernetes

Hajiagha SHR, Hashemi SS, Mahdiraji HA, Azaddel J (2015) Multi-period data envelopment analysis based on Chebyshev inequality bounds. Expert Syst Appl 42(21):7759–7767

Hajiagha SHR, Mahdiraji HA, Tavana M, Hashemi SS (2018) A novel common set of weights method for multi-period efficiency measurement using mean-variance criteria. Measurement 129:569–581

Harris S, Wheeler C (2005) ‘Entrepreneurs’ relationships for internationalization: functions, origins and strategies’. Int Bus Rev. Elsevier 14(2):187–207

Hjarnø L, Syed A, Aro A (2007) Report of interview summaries and Delphi rounds. p 3

Hollensen S (2007) Global marketing: a decision-oriented approach. Pearson Education

Hope, K. et al. (2019) Annual report on European SMEs 2018/2019: research & development and innovation by SMEs

Hsu C-C, Sandford BA (2007) The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval 12(1):10

Hutchinson K, Fleck E, Lloyd-Reason L (2009) An investigation into the initial barriers to internationalization. J Small Bus Enterp Dev. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Jafari-Sadeghi V et al (2019) Home country institutional context and entrepreneurial internationalization: the significance of human capital attributes. J Int Entrep. Springer:1–31

Jafari-Sadeghi V et al (2020) Internationalisation business processes in an under-supported policy contexts: evidence from Italian SMEs. Bus Process Manag J. Emerald Publishing Limited

Kahiya ET (2013) Export barriers and path to internationalization: a comparison of conventional enterprises and international new ventures. J Int Entrep. Springer 11(1):3–29

Kahiya ET (2018) Five decades of research on export barriers: review and future directions. Int Bus Rev. Elsevier 27(6):1172–1188

Karadeniz EE, Göçer K (2007) Internationalization of small firms. Eur Bus Rev. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Karlsen T et al (2003) Knowledge, internationalization of the firm, and inward–outward connections. Ind Mark Manag. Elsevier 32(5):385–396

Korsakiene R (2015) Internationalization of Lithuanian SMEs: investigation of barriers and motives. Econ Bus 26:54

Kreutzer RT, Neugebauer T, Pattloch A (2017) Digital business leadership. In: Digital transformation–Geschäftsmodell-innovation–agile organisation–change-management. Springer

Kumar N (2008) Internationalization of Indian enterprises: patterns, strategies, ownership advantages, and implications. Asian Econ Pol Rev. Wiley Online Library 3(2):242–261

Labate BC, Jungaberle H (2011) The internationalization of Ayahuasca. LIT Verlag Münster

Landau C et al (2016) Institutional leverage capability: creating and using institutional advantages for internationalization. Glob Strateg J. Wiley Online Library 6(1):50–68

Lange T, Ottens M, Taylor A (2000) SMEs and barriers to skills development: a Scottish perspective. J Eur Ind Train. MCB UP Ltd

Laudal T (2011) Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Soc Responsib J 7(2):234–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111111141512

Leonidou LC (2004) An analysis of the barriers hindering small business export development. J Small Bus Manag. Taylor & Francis 42(3):279–302

Leonidou LC, Theodosiou M (2004) The export marketing information system: an integration of the extant knowledge. J World Bus. Elsevier 39(1):12–36

Leonidou LC, Palihawadana D, Theodosiou M (2011) National export-promotion programs as drivers of organizational resources and capabilities: effects on strategy, competitive advantage, and performance. J Int Mark. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 19(2):1–29

Linstone HA, Turoff M (1975) The Delphi method. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

Mahdiraji HA, Hajiagha SHR, Pourjam R (2011) A Grey mathematical programming model to time-cost trade-offs in Project Management under uncertainty. In: IEEE 2011 international conference on Grey systems and intelligent services. IEEE, pp 698–704

Mahdiraji HA, Kazimieras Zavadskas E, Kazeminia A, Abbasi Kamardi A (2019) Marketing strategies evaluation based on big data analysis: a CLUSTERING-MCDM approach. Econ Res-Ekonomska istraživanja 32(1):2882–2892

Mahdiraji HA, Hafeez K, Kord H, Kamardi AA (2020) Analysing the voice of customers by a hybrid fuzzy decision-making approach in a developing country’s automotive market. Manag Decis

Mahmoudi M, Mahdiraji HA, Jafarnejad A, Safari H (2019) Dynamic prioritization of equipment and critical failure modes. Kybernetes 48(9):1913–1941

Marsh HW, Hau K-T, Grayson D (2005) Goodness of fit in structural equation models. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Mejri K, Umemoto K (2010) Small-and medium-sized enterprise internationalization: towards the knowledge-based model. J Int Entrep. Springer 8(2):156–167

Mendy J, Rahman M (2019) Application of human resource management’s universal model: an examination of people versus institutions as barriers of internationalization for SMEs in a small developing country. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev. Wiley Online Library 61(2):363–374

Mokhtarzadeh NG, Mahdiraji HA, Beheshti M, Zavadskas EK (2018) A novel hybrid approach for technology selection in the information technology industry. Technol 6(1):34

Morais F, Ferreira JJ (2020) SME internationalisation process: key issues and contributions, existing gaps and the future research agenda. Eur Manag J. Elsevier 38(1):62–77

Mueller-Using S, Urban W, Wedemeier J (2020) Internationalization of SMEs in the Baltic Sea region: barriers of cross-national collaboration considering regional innovation strategies for smart specialization. Growth Chang. Wiley Online Library

Muhammad Azam Roomi and Parrott G (2008) Barriers to development entrepreneurship in Pakistan.Pdf. J Entrep 17(1):59–72

Mulaik SA et al (1989) Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull. American Psychological Association 105(3):430

Narayanan V (2015) Export barriers for small and medium-sized enterprises: a literature review based on Leonidou’s model. Entrepreneurial Bus Econ Rev. Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Krakowie 3(2):105–123

Ng HS, Kee DMH (2012) The issues and development of critical success factors for the SME success in a developing country. Int Bus Manag 6(6):680–691

Oviatt BM, McDougall PP (2005) Defining international entrepreneurship and modeling the speed of internationalization. Entrep Theory Pract. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 29(5):537–553

Paul J (2020) SCOPE framework for SMEs: a new theoretical lens for success and internationalization. Eur Manag J. Elsevier

Paul J, Parthasarathy S, Gupta P (2017) Exporting challenges of SMEs: a review and future research agenda. J World Bus. Elsevier 52(3):327–342

Pavlák M (2018) Barriers to the internationalization of Czech SMEs. Eur Res Stud J 21(2):453–462

Pinho JC, Martins L (2010) Exporting barriers: insights from Portuguese small-and medium-sized exporters and non-exporters. J Int Entrep. Springer 8(3):254–272

Rahman M, Uddin M, Lodorfos G (2017) Barriers to enter in foreign markets: evidence from SMEs in emerging market. Int Mark Rev 34(1):68–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2014-0322

Ratten V et al (2007) Internationalisation of SMEs: European comparative studies. Int J Entrep Small Bus. Inderscience Publishers 4(3):361–379

Ratten V et al (2017) Family entrepreneurship and internationalization strategies. Rev Int Bus Strateg. Emerald Publishing Limited

Raymond MA, Kim J, Shao AT (2001) Export strategy and performance: a comparison of exporters in a developed market and an emerging market. J Glob Mark. Taylor & Francis 15(2):5–29

Rezaei M, Jafari-Sadeghi V, Bresciani S (2020) What drives the process of knowledge management in a cross-cultural setting. Eur Bus Rev. Emerald Publishing Limited

Ribau CP, Moreira AC, Raposo M (2018) SME internationalization research: mapping the state of the art. Canadian J Adm Sci/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration. Wiley Online Library 35(2):280–303

Romanello R, Chiarvesio M (2019) Early internationalizing firms: 2004–2018. J Int Entrep. Springer 17(2):172–219

Roy A, Sekhar C, Vyas V (2016a) Barriers to internationalization: a study of small and medium enterprises in India. J Int Entrep 14(4):513–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-016-0187-7

Roy A, Sekhar C, Vyas V (2016b) Barriers to internationalization: a study of small and medium enterprises in India. J Int Entrep. Springer 14(4):513–538

Rundh B (2007) International marketing behaviour amongst exporting firms. Eur J Mark. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Rutashobya L, Mukasa D, Jaensson J-E (2005) Networks, relationships and performance of small and medium enterprises in the shipping sub-sector in Tanzania, in IMP Conference at Rotterdam

Saarani AN, Shahadan F (2013) The determinant of capital structure of SMEs in Malaysia: evidence from enterprise 50 (E50) SMEs. Asian Soc Sci. Canadian Center of Science and Education 9(6):64

Sadeghi VJ, Biancone PP (2018) How micro, small and medium-sized enterprises are driven outward the superior international trade performance? A multidimensional study on Italian food sector. Res Int Bus Financ. Elsevier 45:597–606

Sadeghi VJ et al (2018) How does export compliance influence the internationalization of firms: is it a thread or an opportunity? J Glob Entrep Res. Springer 8(1):3

Sadeghi VJ et al (2019) An institution-based view of international entrepreneurship: a comparison of context-based and universal determinants in developing and economically advanced countries. Int Bus Rev. Elsevier 28(6):101588

Saridakis G et al (2019) ‘SMEs’ internationalisation: when does innovation matter?’. J Bus Res. Elsevier 96:250–263

Schmid D, Morschett D (2020) Decades of research on foreign subsidiary divestment: what do we really know about its antecedents? Int Bus Rev. Elsevier 29(4):101653

Senik ZC et al (2010) Influential factors for SME internationalization: evidence from Malaysia. Int J Econ Manag 4(2):285–304

Shah TH, Javed S, Syed S (2013) Internationalization of SMES in Pakistan: a brief theoretical overview of controlling factors. J Manag Sci 7(2)

Shaw V, Darroch J (2004) Barriers to internationalisation: a study of entrepreneurial new ventures in New Zealand. J Int Entrep 2(4):327–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-004-0146-6

Shoham A, Albaum GS (1995) Reducing the impact of barriers to exporting: a managerial perspective. J Int Mark. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA 3(4):85–105

Singh G, Pathak RD, Naz R (2010) Issues faced by SMEs in the internationalization process: results from Fiji and Samoa. Int J Emerg Mark. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Soto JLG (2015) Annual report 2014. Revista de Educacion 368:274–286

Sox CB, Kline SF, Crews TB (2014) Identifying best practices, opportunities and barriers in meeting planning for generation Y. Int J Hosp Manag. Elsevier Ltd 36:244–254

Steurer J (2011) The Delphi method: an efficient procedure to generate knowledge. Skelet Radiol 40(8):959–961

Su¡rez-Ortega, S. (2003) Export barriers: insights from small and medium-sized firms. Int Small Bus J. SAGE Publications 21(4):403–419

Sukumar A, Jafari-Sadeghi V, Garcia-Perez A, Dutta DK (2020) The potential link between corporate innovations and corporate competitiveness: evidence from IT firms in the UK. J Knowl Manag. Emerald Publishing Limited

Taghavifard MT, Amoozad Mahdiraji H, Alibakhshi AM, Zavadskas EK, Bausys R (2018) An extension of fuzzy SWOT analysis: an application to information technology. Info 9(3):46

Tesfom G, Lutz C (2006) A classification of export marketing problems of small and medium sized manufacturing firms in developing countries. Int J Emerg Mark. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Toma C, Picioreanu I (2016) The Delphi technique: methodological considerations and the need for reporting guidelines in medical journals. Int J Public Health Res 4(6):47–59

Treviño LJ, Doh JP (2020) Internationalization of the firm: a discourse-based view. J Int Bus Stud. Springer:1–19

Uner MM et al (2013) Do barriers to export vary for born globals and across stages of internationalization? An empirical inquiry in the emerging market of Turkey. Int Bus Rev. Elsevier 22(5):800–813

Vahlne J-E, Johanson J (2017) From internationalization to evolution: the Uppsala model at 40 years. J Int Bus Stud. Springer 48(9):1087–1102

Welch LS, Luostarinen R (1988) Internationalization: evolution of a concept. J Gen Manag. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, UK 14(2):34–55

Welch C, Paavilainen-Mäntymäki E (2014) Putting process (back) in: research on the internationalization process of the firm. Int J Manag Rev. Wiley Online Library 16(1):2–23

Yoshino N, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2018) The role of SMEs in Asia and their difficulties in accessing finance. Asian Development Bank Institute

Zain M, Ng SI (2006) ‘The impacts of network relationships on SMEs’ internationalization process. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev. Wiley Online Library 48(2):183–205

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rezaei, M., Ferraris, A., Heydari, E., Rezaei, S. (2021). How Do Experts Think? An Investigation of the Barriers to Internationalisation of SMEs in Iran. In: Jafari-Sadeghi, V., Amoozad Mahdiraji, H., Dana, LP. (eds) Empirical International Entrepreneurship. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68972-8_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68972-8_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-68971-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-68972-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)