Abstract

Treatment and management guidelines for GCA slightly vary between international and national task forces. Therefore, this chapter provides an overview on currently available recommendations of the EULAR task force last updated in 2018, the BSR and BHPR guidelines from 2010, the recommendations of the French Study Group for Large Vessel Vasculitis from 2016 and the guidelines of the Swedish Society of Rheumatology from 2019, which were identified in the literature and reviewed for this book chapter. Besides, the relevant EULAR recommendations for the use of glucocorticoids in rheumatic diseases from 2013 and for imaging from 2018 together with the interdisciplinary recommendations for FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging of the Cardiovascular and Inflammation and Infection Committees of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), the Cardiovascular Council of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI), and the PET Interest Group (PIG), endorsed by the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) from 2018 were assessed to summarize current evidence necessary for monitoring of GCA and its comorbidities.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Treatment and management guidelines for GCA slightly vary between international and national task forces. Therefore, this chapter provides an overview on currently available recommendations of the EULAR task force last updated in 2018 [1], the BSR and BHPR guidelines from 2010 [2], the recommendations of the French Study Group for Large Vessel Vasculitis from 2016 [3] and the guidelines of the Swedish Society of Rheumatology from 2019 [4] were identified in the literature and reviewed for this book chapter. Besides, the relevant EULAR recommendations for the use of glucocorticoids in rheumatic diseases from 2013 [5] and for imaging from 2018 [6] together with the interdisciplinary recommendations for FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging of the Cardiovascular and Inflammation and Infection Committees of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), the Cardiovascular Council of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI), and the PET Interest Group (PIG), endorsed by the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) from 2018 [7] were assessed to summarize current evidence necessary for monitoring of GCA and its comorbidities.

1 General Aspects

General recommendations can be divided into those for time of diagnosis, for monitoring of GCA and those concerning adverse events and comorbidities. Details from the above-mentioned recommendations and guidelines for each of these situations are summarized in Table 7.1. Although not specified in these recommendations, the aim of treat-to-target is important for GCA as for other chronic rheumatic diseases, too, with remission being defined as lack of disease activity as the principal target of disease management. However, an aortic aneurysm may develop even without detectable clinical activity, and even years after disease outset [8]. Such caveats have to be kept in mind as peculiar issues in the management of GCA, arguing for prolonged monitoring even without detectable disease activity over years.

First, treatment is recommended to be initiated as soon as diagnosis is made to prevent further complications. Comorbidities predisposing to an increased risk for worse course of the disease or adverse events to medications have to be considered before start of treatment (see Chap. 6). Patients and their carers should be fully informed about management and risks of treatment.

For monitoring, the EULAR task force recommends assessment of symptoms, clinical findings, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels for monitoring of disease activity ([1] recommendation 10). For clinical examination, monitoring is primarily based on symptoms (like jaw and tongue claudication, visual symptoms, vascular claudication of limbs), clinical findings (like bruits and asymmetrical pulses, polymyalgic symptoms, osteoporotic risk factors and fractures). The UK guidelines add a specific recommendation to pay particular attention to the predictive features of ischemic neuro-ophthalmic complications [2]. Concerning laboratory biomarkers, also the French guidelines do explicitly not recommend measuring biomarkers other than C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and fibrinogen for monitoring disease activity [3]. Additional laboratory biomarkers maybe necessary for monitoring of GCA complications, comorbidities, and adverse events of GCA-related treatment.

Concerning the imaging biomarkers, the EULAR recommendation for imaging states that imaging “might be helpful in patients with suspected flare, especially when clinical and laboratory parameters are inconclusive” and that “MRA, CTA and/or US may be used for long-term monitoring of structural damage, particularly to detect stenosis, occlusion, dilatation and/or aneurysms, on an individual basis” ([6] recommendation 10 and 11), while the other international consensus on imaging does definitely not support a value of FDG-PET/CT(A) for evaluating response to treatment [7]. It is argued that a positive 18F-FDG-PET persists in up to 60% of patients in full clinical remission, and using sonography, residual changes often remain visible for several months in extracranial arteries.

Important to note, that—if necessary—times of stable remission should be selected for elective surgical interventions or reconstructive surgery (recommendation 9, [1]), while for emergency situations repair of an aortic lesion should be scheduled once the systemic inflammatory response has subsided [3].

2 Glucocorticoids as First-Line Treatment

Glucocorticoid (GC) therapy is still considered as first-line therapy in GCA, despite their multiple adverse events. GCs should be started immediately after diagnosis and information of the patient. If the symptoms of GCA do not respond rapidly to high-dose GC treatment, followed by resolution of the inflammatory response, the question of an alternative diagnosis should be raised.

Recommendations for optimal dosage and dose reduction of GCs differ between EULAR and national guidelines (Tables 7.2 and 7.3). EULAR experts start with 40–60 mg/day prednisone-equivalent for induction of remission in active GCA and recommend tapering the GC dose to a target dose of 15–20 mg/day within 2–3 months and after 1 year to ≤5 mg/day. In case of signs and symptoms of reactivated disease, the dosage of GCs should be increased to the latest effective dose and GC-sparing agents be considered (see Sect. 7.3). Specific recommendations with higher dosage regimens apply to ocular and aortic aneurysmatic involvement (Table 7.3).

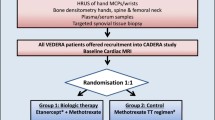

Monitoring is considered essential for treatment adaptions in GCA and includes: clinical signs and symptoms of GCA-activity and GCA complications, treatment-related adverse events, and comorbidities. The schedule for monitoring in relation to recommended dosages of GCs is depicted in Fig. 7.1. For monitoring after 18 months of disease duration, further clinical schedules depend on residual disease activity. Chest radiographs, echocardiography, PET, or MRI are recommended for early detection of an aortic aneurysm every 2–5 years, and additional bone mineral density may be needed.

Summary of GC schemes in recommendations and guidelines together with UK proposal for monitoring from 2010 (from Table 7.1). Dosages are given for prednisolone equivalents. Reductions of GCs (marked in red) should be recommended only in the absence of any signs and symptoms of GCA (recommendation summarized from Table 7.4). Mo months, wk week

Unfortunately, literature lays out that relapses of GCA under treatment with GCs occur in as many as 47.2% (95% confidence interval 40.0–54.3%) of patients, with more relapses reported in randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) than in observational studies and under shorter GC regimens (rate decrease of 1.7% for one additional month), but independent from initial GC doses (3). As a consequence, GCs alone appear to be insufficient for treatment of GCA in many patients, and GC-sparing agents may become necessary.

3 Glucocorticoid(GC)-Sparing Agents

Because of the wide spectrum of possible GC-related side effects, GC-sparing agents have always been considered as an important issue for treatment of GCA. Therefore, several synthetic and biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have been studied for the GC-sparing effects (Table 7.4). Overall, use of a GC-sparing agent beside GCs has been shown to be a protective factor both against new CV events (HR 0.44 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29–0.66)) as well as the development of aortic dilatation (HR 0.43 (CI 0.23–0.77)) [9]. Thus, GC-sparing agents should be considered especially for patients with insufficient response to GCs alone and patients with pre-existing comorbidities or high risk of GC-related side effects.

Recently, a meta-analysis comparing different GC-sparing agents showed that the two drugs tocilizumab (TCZ), a biological (b)DMARD, and methotrexate (MTX), a conventional (c)DMARD can be considered as GC-sparing agents. Both GC-sparing agents resulted in improved likelihoods of being relapse free with relative risks of 3.54 for TCZ and 1.54 for MTX [10]. At present, the bDMARD TCZ is the only FDA- and EMA-approved GC-sparing agent for the treatment of GCA—as an IL 6 R antagonist it showed efficacy in induction of sustained remission in both a phase II [11] and a phase III study (the GIACTA trial, [12]). The GIACTA trial showed that the risk of flares during TCZ treatment weekly and every other week decreases compared to the placebo group (HR 0.23 (CI 0.11–0.46) and 0.28 (CI, 0.12–0.66), respectively). TCZ co-treatment also resulted in lower cumulative prednisolone doses during trial duration (p < 0.001). To be remembered as a challenge of monitoring, is the suppressive effect of TCZ especially on the CRP biomarker. For monitoring of TCZ, it is important to early detect increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >1.5-fold upper limit of normal, absolute neutrophil counts lower than 0.5–1.0 × 109/L, and platelet counts lower than 50–100 × 103/μL [13,14,15,16]. Blood count, liver function test, and lipid parameters should be evaluated 4–8 weeks after initiation and at 6-month interval thereafter. Live and live-attenuated vaccines should not be given concurrently with TCZ. Although the safety profile of TCZ in GCA appears similar to placebo with comparable numbers of adverse events per 100 patient years, longer follow-up periods in RCT trial are needed to underline its benefit-to-harm ratio [17].

As a consequence of this high level of evidence, the updated EULAR guidelines recommend that “adjunctive therapy should be used in selected patients with GCA (refractory or relapsing disease, the presence or an increased risk of GC-related adverse events or complications) using TCZ.” MTX is only considered as an alternative (Table 7.5). MTX is not approved for the treatment of GCA and although lower dosages have not been shown to be effective, two independent meta-analyses of current literature revealed a beneficial effect of MTX in GCA [10, 18].

Only a few other agents have been tested as possible GC-sparing agents so far [19]. Although a randomized-controlled trial showed that the bDMARD abatacept (ABA), an inhibitor of the T-cell receptor CTLA4, may be useful to maintain remission in GCA-patients [20], ABA was not so effective in this trial. Another open-label study suggested that the bDMARD ustekinumab, which targets the interleukins IL12 and IL23, could be useful for the treatment of patients with refractory GCA [21]. In cultured GCA arteries, inhibition of IL-12/IL-23p40 tended to reduce IFNγ and IL-17 mRNA production and to increase the Th17 inducers IL-1β and IL-6 [22]. Now, further studies are required to assess whether ABA and ustekinumab extend our repertoire of adjunctive therapies to reduce relapses or as a GC-sparing agents in GCA. The interleukin-1 binding bDMARD, anakinra has been successfully used only in a few patients with refractory GCA. Blockade of TNF-alpha turned out already earlier to be ineffective as a GC-sparing approach [23, 24].

4 Treatment of Comorbidities/Adjuvant Therapies

Comorbidities may occur as a consequence of higher age, as complications of GCA itself and GCA-treatment. For optimal treatment of GCA-patients, all of these issues have to be considered, and deterioration of only one of the comorbidities may result in severe complications with increased morbidity or even mortality.

Although treatment of comorbidities is essential for the optimal outcome of GCA, only a few recommendations refer to comorbidities (Tables 7.6):

-

1.

Concerning the recommendations on antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy, low-dose aspirin is advised or at least should be considered for GCA-patients without contraindication according to national guidelines, but the EULAR task force recommends low-dose aspirin or at least to consider it only for patients with other indications or in special situations (Table 7.6).

-

2.

Bone protection is recommended by the UK guidelines for GCA.

-

3.

Proton pump inhibitors for gastrointestinal protection should be considered according to the UK guidelines for GCA.

-

4.

The systematic prescription of statins is not recommended by the French guidelines for GCA.

-

5.

Recent evidence confirms the use of GC-sparing agents to reduce GCA-related comorbidities (see Sect. 7.3). Besides, monitoring is recommended especially for osteoporosis, CV-risk factors (including arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus), and CV disease.

Further recommendations for other comorbidities are not included in the available EULAR and national GCA-specific recommendations, so that risk and comorbidity-specific recommendations have to be adapted for GCA-patients. For example, the risk of infections is estimated to be twofold increased in GCA-disease [26, 27], with the need of appropriate patients’ information, monitoring and treatment, independent from the GCA-specific recommendations.

References

Hellmich B, Agueda A, Monti S, et al. 2018 Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):19–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215672.

Dasgupta B, Borg FA, Hassan N, et al. BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1594–7.

Bienvenu B, Ly KHH, Lambert M, et al. Management of giant cell arteritis: recommendations of the French Study Group for Large Vessel Vasculitis (GEFA). Rev Med Interne. 2016;37:154–65.

Turesson C, Börjesson O, Larsson K, Mohammad AJ, Knight A. Swedish Society of Rheumatology 2018 guidelines for investigation, treatment, and follow-up of giant cell arteritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2019;00:1–7.

Duru N, van der Goes MC, Jacobs JWG, et al. EULAR evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations on the management of medium to high-dose glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1905–13.

Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Duftner C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:636–43.

Slart RHJA, Glaudemans AWJM, Chareonthaitawee P, et al. FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica: joint procedural recommendation of the EANM, SNMMI, and the PET Interest Group (PIG), and endorsed by the ASNC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1250–69.

García-Martínez A, Arguis P, Prieto-González S, Espígol-Frigolé G, Alba MA, Butjosa M, Tavera-Bahillo I, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Cid MC. Prospective long term follow-up of a cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis screened for aortic structural damage (aneurysm or dilatation). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1826–32.

de Boysson H, Liozon E, Espitia O, et al. Different patterns and specific outcomes of large-vessel involvements in giant cell arteritis. J Autoimmun. 2019;103:102283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2019.05.011.

Berti A, Cornec D, Medina Inojosa JR, Matteson EL, Murad MH. Treatments for giant cell arteritis: meta-analysis and assessment of estimates reliability using the fragility index. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48:77–82.

Villiger PM, Adler S, Kuchen S, Wermelinger F, Dan D, Fiege V, Bütikofer L, Seitz M, Reichenbach S. Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1921–7.

Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:317–28.

Shovman O, Shoenfeld Y, Langevitz P. Tocilizumab-induced neutropenia in rheumatoid arthritis patients with previous history of neutropenia: case series and review of literature. Immunol Res. 2015;61:164–8.

European Medicines Agency. Find medicine—RoActemra. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/000955/human_med_001042.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed 18 Nov 2017.

Moots RJ, Sebba A, Rigby W, Ostor A, Porter-Brown B, Donaldson F, Dimonaco S, Rubbert-Roth A, van Vollenhoven R, Genovese MC. Effect of tocilizumab on neutrophils in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis: pooled analysis of data from phase 3 and 4 clinical trials. Rheumatology. 2016;56:541–9.

Vitiello G, Orsi Battaglini C, Radice A, Carli G, Micheli S, Cammelli D. Sustained tocilizumab-induced hypofibrinogenemia and thrombocytopenia. Comment on: “Tocilizumab-induced hypofibrinogenemia: a report of 7 cases” by Martis et al., Joint Bone Spine 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.04.008. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:649–50.

Schirmer M, Muratore F, Salvarani C. Tocilizumab for the treatment of giant cell arteritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14(5):339–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2018.1468251.

Mahr AD, Jover JA, Spiera RF, Hernández-García C, Fernández-Gutiérrez B, Lavalley MP, Merkel PA. Adjunctive methotrexate for treatment of giant cell arteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2789–97.

Watelet B, Samson M, de Boysson H, Bienvenu B. Treatment of giant-cell arteritis, a literature review. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27:747–54.

Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the treatment of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:837–45.

González-Gay MA, Pina T, Prieto-Peña D, Calderon-Goercke M, Blanco R, Castañeda S. The role of biologics in the treatment of giant cell arteritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:65–72.

Espígol-Frigolé G, Planas-Rigol E, Lozano E, Corbera-Bellalta M, Terrades-García N, Prieto-González S, García-Martínez A, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Grau JM, Cid MC. Expression and function of IL12/23 related cytokine subunits (p35, p40, and p19) in giant-cell arteritis lesions: contribution of p40 to Th1- and Th17-mediated inflammatory pathways. Front Immunol. 2018;9:809.

Hoffman GS, Cid MC, Rendt-Zaga KE, et al. Infliximab for maintenance of glucocorticosteroid-induced remission of giant cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:621–31.

Seror R, Baron G, Hachulla E, et al. Adalimumab for steroid sparing in patients with giant-cell arteritis: results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:2074–81.

Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, Carreño L, López-Longo J, Figueroa M, Belzunegui J, Mola EM, Bonilla G. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of etanercept in patients with giant cell arteritis and corticosteroid side effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:625–30.

Mohammad AJ, Englund M, Turesson C, Tomasson G, Merkel PA. Rate of comorbidities in giant cell arteritis: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:84–90.

Petri H, Nevitt A, Sarsour K, Napalkov P, Collinson N. Incidence of giant cell arteritis and characteristics of patients: data-driven analysis of comorbidities. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:390. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22429.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Schirmer, M., McCutchan, R. (2021). Treatment and Management. In: Salvarani, C., Boiardi, L., Muratore, F. (eds) Large and Medium Size Vessel and Single Organ Vasculitis. Rare Diseases of the Immune System. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67175-4_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67175-4_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-67174-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-67175-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)