Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by the DSM-5 definition by two major developmental deficits: (a) impairments of social-emotional reciprocity, deficits in non-verbal social communication and deficits in reciprocal relationship and (b) restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities (RRBI). This book addresses the second diagnostic criterion- RRBI. It starts by describing developmental and neurobiological aspects of RRBI, moves on to relations with other ASD characteristics and participation in everyday life, all the way to assessment and intervention which addresses RRBI along the life span.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by the DSM-5 definition by two major developmental deficits: (a) impairments of social-emotional reciprocity, deficits in non-verbal social communication and deficits in reciprocal relationship and (b) restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities (RRBI). The DSM-5 also defines a severity rating applied for both domains of impairment, ranging from “Level 1: requiring support” to “Level 3: requiring substantial support”.

The onset of the above-mentioned symptoms occurs in the early developmental period, and these symptoms result in impairment in daily functioning. Research shows that the diagnosis of ASD remains stable across the life span of an individual (Esbensen, Seltzer, Lam, & Bodfish, 2009). Restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior and interests, one of the core criteria for ASD, is an umbrella term for the broad class of behaviors linked by repetition, rigidity, invariance, and inappropriateness to the place and context (Turner, 1997). These behaviors and interests were originally identified by Leo Kanner, who suggested that they are characterized by invariant nature, high frequency, repetition, and desire of sameness (Kanner, 1943).

The DSM-5 (APA, 2013) classifies this domain into four types of symptoms: (1) repetitive and stereotyped speech, movement or use of objects; (2) routines, rituals and resistance to change; (3) circumscribed and restricted interests, and (4) hypo- or hyper-reactivity to sensory input, including unusual sensory interests. Being the defining core features of ASD, repetitive behaviors and movements, rituals or special interests are prevalent across all individuals with ASD. However, the diagnostic criteria for autism include the presence or history of any two of the four types of RRBI symptoms.

Repetitive and stereotyped speech, movement or use of objects. The first DSM-5 criterion of RRBI relates to repetitive and stereotyped speech, movement or use of objects, such as simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, and idiosyncratic phrases. Repetitive and stereotyped use of language, such as repeating favorite sounds, words, sentences or songs or asking the same question over and over again (APA, 2013), is the first common form of such ritualized behavior. Repetitive verbalization can be communicative in nature, representing the child’s processing difficulties and/or their emotional state. Indeed, this criterion was previously included in the social communication part of the Autism definition (DSM-IV; APA, 1994). However, it may have a non-communicative purpose, where a response is not expected.

One of the most common RRBI in ASD is stereotyped movements (SM) or stereotypies, which have been described as patterned movements that are highly consistent, invariant and repetitious; excessive in rate, frequency and/or amplitude; and inappropriate and odd and lack an obvious goal (Turner, 1999). These motor behaviors are not specific to ASD. In fact, they characterize early typical development and usually diminish by 2 years of age (Fyfield, 2014). They, however, differ significantly from aimed and planned movements shown along the lifespan in typically developed individuals. Typical examples of such movements in ASD are rhythmic body rocking in a sitting or standing position, various arm and hand movements such as arm waving and hand flapping, and repetitive pacing and jumping (Schopler, 1995).

Stereotyped movements are often problematic for the observers as they may differ in their degree of “inappropriateness” or “oddness” in various contexts. For example, repetitive leg movement together with concentration may look more “appropriate” than hand flapping in front of the eyes or intensive rocking movements while standing and talking. However, this criterion is prone to subjective and cultural-oriented judgment (Gal, 2011).

The third characteristic of the first RRBI category is the repetitive manipulation of objects, which relates to the repetition of the same motor activity used to manipulate the physical environment. Typical repetitive manipulation of objects among individuals with ASD may include lining up objects, flicking light switches, or displaying repetitive manipulation of an object such as a string, rubber tubing or toy. A child may stack blocks over and over again without demonstrating pride in the accomplishment, dump toys or turn light switches on and off repeatedly. This kind of RRBI characterizes the play of children with ASD, who, for example, rather than playing imaginary play such as a racing or driving game may be preoccupied with spinning the wheels on a toy car (Gal, 2011).

Routines, Rituals and Resistance to Change

The second category of the RRBI criterion of the DSM-5 includes routines, rituals and resistance to change, such as extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals and a need to take the same route or eat the same food every day (APA, 2013). Indeed, many individuals with ASD appear to adhere inflexibly to routines, do not tolerate changes in routine, and suffer from subsequent anxiety when novel events occur unexpectedly. First-hand accounts of individuals with ASD suggest an extreme need for structure and predictability. Changes in the routines may, therefore, cause extreme distress, resulting in insistence on inflexible routines, which, in turn, may serve as a strategy to overcome change-related anxiety. Along with the adherence to routines, many individuals with ASD perform ritualistic behaviors that are often compulsive in nature, such as a demand for consistency in their environment or an apparent compulsion to always act in exactly the same way at a specific time (Schopler, 1995) even if the behavior may be irrelevant and inappropriate to the environment’s needs and demands. For example, a child with ASD may feel compelled to repetitively play with water whenever he sees a tap. Another may have a strong need to put things away even when they are still needed. Some insist on eating the same foods at the same time and use the same utensils or eat foods of a specific brand only. These behaviors may reflect the discomfort of the individual with ASD and simultaneously may create great difficulties for their social environment and may negatively affect their ability to participate in everyday life.

Circumscribed and Restricted Interests

The third category of the RRBI criterion is circumscribed and restricted interests such as strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects and excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests (APA, 2013). Indeed, the development of unusual, narrow and circumscribed interests or an obsession or fascination with a particular topic is a hallmark symptom attributed to individuals on the autism spectrum, described as a specific field of knowledge that the individual is passionate about or restricted and circumscribed interests that are abnormal in intensity (Klin, Danovitch, Merz, & Volkmar, 2007). These behaviors may range from unusual activities such as memorizing serial numbers to more typical hobbies such as an intense interest in math. For children, one way through which these interests are shown is attachment to a specific object, often different in nature than the soft and cuddly transitional objects that children with typical development tend to be attached to. Some children with ASD carry these objects around and refuse to part with them. Others may show an extreme reaction—which may look bizarre—whenever they come into contact with a particular object (Volkmar, 2005). Later in life, children with ASD may develop specific interests or a peculiar fascination with subjects rather than objects. Typical examples are phone numbers, weather reports, and commercials. Such interests may be more complex, such as diagrams, maps, or stories by a specific writer (Schopler, 1995). The narrow interests, often pursued to the exclusion of other more appropriate behaviors, can substantially interfere with social functioning and academic success. Coupled with impairments in social development, which is a clear mark of the disorder, the narrow interests create further “weirdness” and the preoccupations, rigidity, and invariant nature of activities in individuals with ASD prevent them from developing peer relations (Cohen & Volkmar, 1997).

However, these special interests also have the potential to induce motivation as they lead to a positive feeling by engaging in activities associated with the area of interest. For example, a child who obsesses over dates and other numbers may enjoy assisting in a library. In adults with ASD, the aspired goal of matching skills, special interests and jobs, possibly satisfies intrinsic motivation and promotes employees with ASD in various aspects of their jobs and career, however, barriers are high and compromise is often essential (Goldfarb, Gal, & Golan, 2019).

Hypo- or Hyper-Reactivity to Sensory Input/Unusual Sensory Interests

The fourth and final category of RRBI in the DSM-5 is hypo- or hyper-reactivity to sensory input/unusual sensory interests, for example, apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, and visual fascination with lights or movement (APA, 2013). While sensory differences have been documented in Kanner’s early reports of ASD (Kanner, 1943), they were not included as diagnostic criteria in the following DSMs. However, Over the past two decades, professionals in numerous disciplines have increasingly recognized the sensory features of ASD (Ben-Sasson, Gal, Fluss, Katz-Zetler, & Cermak, 2019; DuBois, Lymer, Gibson, Desarkar, & Nalder, 2017), estimating their prevalence to be 60–95% (Lane, Molloy, & Bishop, 2014; Tomchek & Dunn, 2007), and associating them with repetitive behaviors (Gabriels et al., 2008; Gal, Dyck, & Passmore, 2010; Joyce, Honey, Leekam, Barrett, & Rodgers, 2017). In addition, almost all first-hand accounts of people with ASD include sensory issues (e.g., Chamak, Bonniau, Jaunay, & Cohen, 2008). In the current DSM-5 (APA, 2013) sensory characteristics were re-included as part of the second diagnostic criterion, namely RRBI.

Sensory characteristics also called sensory features, refer to patterns of behavior that are suggestive of differences in the manner in which daily sensory stimuli are processed. These features have often been referred to as impairments in sensory modulation, in which an individual has difficulty regulating and organizing the type and intensity of behavioral responses to sensory inputs to match environmental demands. For example, covering the ears in response to an unexpected sound or failure to respond to a painful stimulus (Schaaf & Lane, 2015). These features can manifest in response to touch, sight, sound, taste, smell, and movement, with many individuals presenting several types of symptoms. Sensory features can be classified into three patterns known as sensory over-responsivity (SOR), such as sensitivity to sounds, touch, and food taste or smells; sensory under-responsivity (SUR), such as failure to notice more salient stimuli and sensation seeking, such as fascination and intense interests in sensory stimuli (Miller, Anzalone, Lane, Cermak, & Osten, 2007). These impairments in sensory modulation are further known to present significant restrictions in participation in daily life activities of people with ASD (Dunn, Little, Dean, Robertson, & Evans, 2016; Schaaf, Toth-Cohen, Johnson, Outten, & Benevides, 2011). In fact, according to both research and first-hand accounts, all RRBI have numerous implications on the lives of people with ASD and their families. For example, Stereotyped movements (SM) may fulfill the inner needs of an individual with ASD, but they often appear bizarre and differ significantly from normal movements, and therefore may challenge children in social play, and academic learning, constituting a significant social barrier (Joosten & Bundy, 2010). “High-level” RRBI, such as insistence on sameness or restricted interests, may appear to be inappropriate and therefore can be socially stigmatizing (Cunningham & Schreibman, 2008). Moreover, they may pose difficulties in the process of finding and maintaining employment and may present challenges in interactions with employers and co-workers (Weissman-Nitsan, Schreuer, & Gal, 2019).

This book starts by describing developmental and neurobiological aspects of RRBI, moves on to relations with other ASD characteristics and participation in everyday life, all the way to assessment and intervention which addresses RRBI along the life span.

We set the tone for the book by including the opinions of individuals with ASD speaking about their RRBIs in the chapter titled “It’s in my Nature – Subjective Meanings of RRBIs Voiced by Adults with ASD” by Goldfarb, Zafrani, and Gal. In the various diagnostic systems, RRBI are included as core symptoms of ASD. The conventional medical practice is to immediately consider symptoms as behaviors that indicate disease, illness, and psychopathology and therefore, should be treated and eliminated. However, the neurodiversity movement, with its emphasis on partnership with individuals with autism regarding their lives, has resulted in increased public awareness about ASD. First-hand accounts of individuals with ASD speaking about their reveal that RRBI actually help them cope in everyday life and regulate arousal, attention, sensations, and emotions; they also assist in feeling secure and coping with social interactions and unexpected and undesired changes. Thus, RRBIs that are helpful to individuals with ASD should not be treated by others merely as symptoms that need to be eliminated. It is in the eye of the beholder, and the unique experiences and needs of individuals with ASD need to be accepted. As a young woman with ASD commented about her repetitive behavior with her mobile phone: “No one would tell a handicapped man sitting in a wheelchair to get up and start walking. It’s the same thing; it doesn’t distract me, just the opposite; to me, it’s accessibility.” We hope that, while reading this book, one will continue to hold and honor these personal accounts.

In the next two chapters, Poleg and Zachor review potential neurological mechanisms underlying RRBIs in ASD, and Perets and Offen describe animal models for autism, with a focus on RRBIs. Regarding psychological theories, Poleg and Zachor suggest that the executive function deficit theory—which involves mechanisms of planning, controlling, and regulating higher-order mental processes—offers a good explanation for the observed RRBI. Structural brain abnormalities in the basal ganglia and the striatum are suggested, with some data supporting the link between basal ganglia size, shape, or volume and the severity of RRBI among individuals with ASD; however, Poleg and Zachor conclude by stating that there are no conclusive and convincing data from clinical trials regarding the significance of structural changes in the brains of individuals with ASD. Next, regarding genetic abnormalities, ASD evidently has a robust genetic component, with strong familial inheritance patterns and the potential involvement of approximately 1000 genes. Research supports that RRBIs have a strong genetic component, and there is some evidence that an imbalance in the neurotransmission system of dopamine, GABA, and serotonin (5-HT) have a role in RRBI. Perets and Offen describe animal models for autism, with a focus on RRBI. They describe findings from three different mouse models: a mouse model based on mutations found in humans with ASD (the mouse genome is altered to include the same mutations as those found in humans with ASD), a mouse model of ASD involving neurodevelopmental processes during pregnancy, and a multifactorial mouse model that includes a combination of factors other than genetic mutations or biological markers that account for the observed ASD-related symptoms. The studies on these mouse models—similar to the research on neurological mechanisms among humans—emphasize our current understanding of ASD in humans, that is, some ASD symptoms may or may not be associated with various genetic and environmental factors, and the etiology of ASD and RRBI in most individuals with these diagnoses remains an enigma.

The next chapter describes RRBI. Uljarević, Hedley, Linkovski, and Leekam, addresses the underlying mechanisms and developmental trajectories of restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRB) in typical and atypical development. These authors mainly focus on RRB which typically precede IS, and offer a summary regarding the conceptualization and classification of RRB among children with typical and atypical development. RRB most often emerge earlier in development and fade throughout childhood whereas IS typically appear later and more gradually throughout development. They suggest that RRB are common among children with typical development and among children with diagnoses other than ASD. Therefore, a dimensional approach rather than a disorder-based approach may be more appropriate for conceptualization, research and intervention because RRB are prevalent in many neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, and genetic disorders.

In the following chapter, Lane presents an in-depth account of sensory subtypes associated with ASD. The focus of this chapter is on sensory features—which are patterns of behavior that are suggestive of differences in the manner in which daily sensory stimuli are processed—and on sensory modulation—which is defined as the ability of the central nervous system to regulate its responses to sensory input. The four sensory quadrants—poor registration, sensory sensitivity, sensory avoidance, and sensory-seeking behaviors—and the structures, mechanisms, and impairment associated with the various sensory subtypes are described, along with the seven proposed sensory subtype models in ASD, which identify distinct patterns of sensory features among toddlers, children, and adolescents but not adults. Lane concludes that more studies are needed to delineate the various sensory subtypes and their developmental trajectories to allow more specific assessments and interventions. More data would also be helpful in distinguishing between sensory phenomena, which should be targeted for intervention versus this that actually assist individuals with autism in their coping with everyday activities and thus should be maintained and tailored for further development and enhanced well-being.

The section regarding the descriptive nature of RRBI is concluded with a chapter by Shulman and Bing, who address differences between females and males with ASD with regards to RRBI. Different methodologies including quantitative and qualitative paradigms, clinical and epidemiological studies, and methodologies including different informants using different instruments have repetitively demonstrated that more males than females are affected with ASD, a finding that remains unexplained. In this chapter, Shulman and Bing discuss these sex/gender differences in relation to RRBI. They offer convincing data that girls are diagnosed at an older age than boys and present a different clinical picture of behavioural symptoms, including RRBI from males. The sex/gender differences change over the course of life, with relatively few differences in toddlerhood; more differences emerging in early childhood, school-age, and early adolescence; and changes occurring again in later adolescence and adulthood, after which there seems to be a reduction in the sex/gender differences in RRBI. Overall, females present fewer of the diagnostic RRBI criteria than males but more self-injurious behaviors, compulsive behaviors, and insistence on sameness than males They argue that the fact that most diagnostic instruments were standardized with males hinders our ability to diagnose girls and to capture their unique RRBI profiles. The chapter includes a review of the developmental trajectory of RRBIs in males and females as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the most common diagnostic systems in identifying the sex/gender differences in RRBI. It is clear that more research comparing males and females with ASD is required, and not only in relation to RRBI.

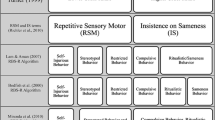

The measurement of RRBI in ASD is presented in the subsequent chapter by Young and Lim. They outline the challenges involved in operationalizing these behaviors and discuss the general strengths and weaknesses of the various available types of assessment tools: questionnaires, interviews, and direct observation scales. The available specific instruments for assessment during infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, as well as those suitable across the life span are each reviewed, including the most common assessment measures utilized to assess RRBI: the repetitive behavior scale-revised (RBS-R), the autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R), and the repetitive behavior questionnaire (RBQ). Many assessment tools exist; however, considering the heterogeneity of RRBI, the authors suggest that no single assessment tool is appropriate. They further discuss the fact that no assessment tool was designed and validated to specifically assess RRBI as defined in DSM-5 and state that future research should address this need.

The next four chapters focus on the relations between RRBI and language, social interactions, anxiety, and eating difficulties and disorders, respectively. Dromi, Oren, and Mimouni-Bloch review language development among children with ASD. They discuss speech production, comprehension, and development and review research regarding echolalia, verbal rituals, stereotyped language, and memorized speech, which are part of the symptoms listed in DSM-5 under RRBIs. Dromi and colleagues argue that the distinction between communication, language, and speech is vital for describing the linguistic profile of children with ASD because young children with ASD are more likely to have weaker language comprehension skills than speech production skills, whereas the opposite is true for typically developing children. Important linguistic milestones, skills, and abilities such as babbling, age of first words, pitch, voice, intonation, pronoun reversals, and difficulties in linguistic inferences of metaphors and idioms are also reviewed. Owing to the paucity of research, the relations between severity of RRBI and various language skills is not well known; thus, future research should address this issue considering severity of symptoms, level of functioning, and subtypes of RRBI across the lifespan. The next chapter, by Ghanouni and Jarus, discusses challenges in social interactions and communication skills in relation to RRBI. After reviewing the challenges that individuals with ASD experience in social interactions, such as difficulties in perspective-taking, cognitive empathy, and affective empathy, and in processing social stimuli and drawing attention to them, Ghanouni and Jarus describe common underlying mechanisms for RRBI and impairments in social interactions, such as sensory processing and executive functioning deficits and the possibilities that impairments in social interactions result from RRBI and/or vice versa. One example which can fit all three possibilities is the transaction among anxiety, RRBI and social impairments in that any one or two of the three—RRBI, social difficulties or/and anxiety can initiate and then result in heightened levels of one or more of these, as well as other components. The role of anxiety in ASD and RRBI is presented in the next chapter by Ben-Sasson and Stephenson, who in their in-depth discussion, describe RRBI in anxiety-related disorders (ARDs) and in ASD and examine the important question similar to the egg-and-chicken problem—Does anxiety precede and lead to RRBI? Does RRBI cause anxiety? Is there a third mechanism associated with both? They offer a detailed description regarding the developmental trajectory of anxiety among individuals with ASD and on how to make a differential diagnosis between ASD and ARDs including how to distinguish between RRBIs that are most likely associated with ASD versus OCD. For some individuals with ASD, anxiety may lead to RRBI while for others or at other times, the opposite may be true. It is important to remember that RRBIs actually help some people with ASD to better cope with their anxiety and stress, yet negative reactions from the environment may hinder this adaptive function. Therefore, it is necessary to carefully evaluate RRBI in contexts, to assure that they are not disapproved of, and looked at negatively, just because they seem odd to the lay person.

Eating and feeding problems are prevalent among individuals with autism across the life span. These difficulties are discussed in the next chapter by Enten-Vissoker. Selective eating or food selectivity is the most prevalent eating problem among children with ASD, as displayed by insistence on specific foods, specific methods of food preparation, and mealtime routines. The estimate of young children with ASD who show eating problems is as high 90% compared to about 25–30% among typically developing children. Food selectivity and restriction is a risk factor for under-nutrition, suboptimal growth, social deficits, poor academic progress, deficiencies of vitamins, minerals and amino acids as well as overweight for those with binge eating. Turning to eating disorders, ASD symptoms are prevalent among people with eating disorders, with some evidence that adolescents who develop eating disorders have a childhood history of more repetitive, self-injurious, and compulsive behaviors and insistence on sameness, compared to adolescents who do not develop eating disorders. Although it is difficult to separate physiological aspects of feeding difficulties from behavioral aspects, it is safe to conclude that RRBI and a range of eating problems are interrelated in ASD, with sensory impairment as a possible underlying mechanism. More research is needed to clarify which RRBI are associated with which eating and feeding difficulties for people with ASD across the life span and range of levels of functioning.

The following two chapters focus on intervention. Yaari and Dissanayake offer a thorough evaluation of early intervention regarding RRBI. They highlight that most early intervention programs target symptoms associated with social communication challenges and outcomes rather than RRBI. Although RRBI clearly interfere with learning and social interactions, most families and professionals concentrate more on the social communication difficulties. Both comprehensive treatment models (CTMs) and focused intervention practices (FIPs) involving RRBIs as an outcome and as a predictor of early intervention are described. Family members, professionals, and others have an important role in ensuring that RRBI are carefully evaluated to assure that RRBI that are or may be helpful to individual with ASD are distinguished from those that are not. The take-home message is that the existing data regarding the efficacy of early intervention in the context of RRBI is inconsistent, and therefore more early intervention programs and studies are necessary to achieve a more in-depth understanding of factors that help in reducing RRBI that hinder adaptive daily life skills and well-being. Gal and Ben-Sasson present the “Rep-Mod”, a whole person–environment-focused intervention model that integrates sensory-based and behavior-based intervention techniques, addressing RRBI in individuals with ASD. The strengths of the model lie in its functional analysis regarding the differential advantage or disadvantage of RRBI in the life each individual. Thus, RRBI considered to hinder adaptation and well-being are targeted as behaviors that should be reduced or eliminated, whereas RRBI that are judged as potential assets are integrated into daily life activities to increase adaptation and well-being. The model is dynamic such that each cycle of evaluation, intervention, and post-intervention re-evaluation forms the next entry level for further intervention.

We conclude with a chapter by Bury, Hedley, and Uljarević, on RRBI in the workplace, which brings us back to the personal accounts presented in the first chapter in that RRBI may also serve assets and not necessarily only as undesired symptoms. Individuals with ASD often experience significant difficulties obtaining and maintaining employment. This is reflected in high rates of unemployment and underemployment worldwide. Social communication challenges can lead to difficulties through recruitment and employment processes. In addition, RRBI can present significant barriers to the employment. However, with sufficient support, individuals with autism can not only succeed in the workplace but may even outperform their colleagues in certain domains. This may be due to skills, or “talents”, related to RRBI; for example, attention to detail and tolerance for repetitive tasks. A critical appraisal of the evidence regarding the special talents of individuals with ASD as it pertains to RRBI, is offered, followed by evidence supporting the “autism advantage” in employment specifically. Finally, the authors discuss the benefits of adopting an individualized approach to research and practice, to best identify and support individual strengths and challenges within the workplace.

We end this chapter by referring to precision medicine which advocates considering individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person in treatment and intervention. We hope this book contributes to thinking about RRBI in individuals with ASD using this model. It is interesting to note that a common goal in ASD intervention models is to promote and enhance social communication and interaction skills and to reduce or eliminate RRBI. This practice is most likely based on typical development and the desire to assist individuals with ASD achieve skills that are considered as reflecting typical development. Yet, this approach may miss out on the strengths of some RRBI as described by individuals with ASD. Therefore, we emphasize the need to evaluate RRBI in context and to distinguish among RRBI that are helpful and may promote development and well-being from those that are not. Accordingly, this book includes interdisciplinary, international, evidence-based knowledge addressing RRBI in people with ASD. It is primarily suitable for professionals and students who are working with people with ASD across the life-span. We hope that family members, as well as some individuals with ASD will also find it helpful and interesting.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Ben-Sasson, A., Gal, E., Fluss, R., Katz-Zetler, N., & Cermak, S. (2019). Update of a meta-analysis of sensory symptoms in ASD: A new decade of research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(12), 4974–4996.

Chamak, B., Bonniau, B., Jaunay, E., & Cohen, D. (2008). What can we learn about autism from autistic persons? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77(5), 271–279.

Cohen, D. J., & Volkmar, F. R. (1997). Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Cunningham, A. B., & Schreibman, L. (2008). Stereotypy in autism: The importance of function. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2007.09.006.

DuBois, D., Lymer, E., Gibson, B. E., Desarkar, P., & Nalder, E. (2017). Assessing sensory processing dysfunction in adults and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Brain Sciences, 7, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7080108.

Dunn, W., Little, L., Dean, E., Robertson, S., & Evans, B. (2016). The state of the science on sensory factors and their impact on daily life for children: A scoping review. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 36(2_suppl), 3S–26S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449215617923.

Esbensen, A. J., Seltzer, M. M., Lam, K. S., & Bodfish, J. W. (2009). Age-related differences in restricted repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0599-x.

Fyfield, R. (2014). The rise and fall of repetitive behaviors in a community sample of infants and toddlers (PhD thesis). Cardiff University.

Gabriels, R. L., Agnew, J. A., Miller, L. J., Gralla, J., Pan, Z., Goldson, E., et al. (2008). Is there a relationship between restricted, repetitive, stereotyped behaviors and interests and abnormal sensory response in children with autism spectrum disorders? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2(4), 660–670.

Gal, E. (2011). Nosology and theories of rituals and stereotypies. In J. Matson & P. Sturmey (Eds.), International handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Gal, E., Dyck, M. J., & Passmore, A. (2010). Relationships between stereotyped movements and sensory processing disorders in children with and without developmental or sensory disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2010.09075.

Goldfarb, Y., Gal, E., & Golan, O. (2019). A conflict of interests: The complex role of special interests in employment success of adults with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(9), 3915–3923.

Joosten, A. V., & Bundy, A. C. (2010). Sensory processing and stereotypical and repetitive behaviour in children with autism and intellectual disability. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 57, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00835.x.

Joyce, C., Honey, E., Leekam, S. R., Barrett, S. L., & Rodgers, J. (2017). Anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty and restricted and repetitive behaviour: Insights directly from young people with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3789–3802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3027-2.

Kanner, L. J. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. The Nervous Child, 2(3), 217–250.

Klin, A., Danovitch, J. H., Merz, A. B., & Volkmar, F. R. (2007). Circumscribed interests in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: An exploratory study. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.32.2.89.

Lane, A. E., Molloy, C. A., & Bishop, S. L. (2014). Classification of children with autism spectrum disorder by sensory subtype: A case for sensory-based phenotypes. Autism Research, 7(3), 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1368.

Miller, L. J., Anzalone, M. E., Lane, S. J., Cermak, S. A., & Osten, E. T. (2007). Concept evolution in sensory integration: A proposed nosology for diagnosis. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 135–140. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.2.135.

Schaaf, R. C., & Lane, A. E. (2015). Toward a best-practice protocol for assessment of sensory features in ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(5), 1380–1395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2299-z.

Schaaf, R. C., Toth-Cohen, S., Johnson, S. L., Outten, G., & Benevides, T. W. (2011). The everyday routines of families of children with autism: Examining the impact of sensory processing difficulties on the family. Autism, 15(3), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310386505.

Schopler, E. (1995). Parent survival manual. New York: Plenum Press.

Tomchek, S. D., & Dunn, W. (2007). Sensory processing in children with and without autism: A comparative study using the short sensory profile. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.2.190.

Turner, M. (1997). Towards an executive dysfunction account of repetitive behaviour in autism. In J. Russell (Ed.), Autism as an executive disorder (pp. 57–100). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Turner, M. (1999). Annotation: Repetitive behaviour in autism: A review of psychological research. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(6), 839–849.

Volkmar, F. R. (2005). Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders: Assessment, interventions, and policy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Weissman-Nitsan, M., Schreuer, N., & Gal, E. (2019). Employers’ perspectives regarding reasonable accommodations for employees with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Management & Organization, 25, 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2018.59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gal, E., Yirmiya, N. (2021). Introduction: Repetitive and Restricted Behaviors and Interests in Autism Spectrum Disorders. In: Gal, E., Yirmiya, N. (eds) Repetitive and Restricted Behaviors and Interests in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Autism and Child Psychopathology Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66445-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66445-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-66444-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-66445-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)