Abstract

There is a lot of interest generated in researching the factors that contribute to successful performance of high-tech startups and their growth and scalability to the next level. India, with its unique cultural mix, leadership traits, and funding characteristics, is a leading contributor to high-tech entrepreneurship. This study tries to explore the effect of three variables namely founders’ national culture values, his transformational leadership traits, and the startup culture emanating from the type of funding received on startup performance; specifically in the Indian context. It uses a unique mix of variables which have not been used together in previous researches. Therefore, it would provide immense implications for researchers and practitioners in the fields of entrepreneurship, startup performance, national culture values, transformational leadership, and startup funding.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

“A startup is a temporary organization in search of a scalable, repeatable, profitable business model” (Blank & Dorf, 2012). A high-tech startup is an organization which is new, active, and independent, has paid employees, engages in processes of technological evolution and innovation, and is financed by venture capital (Luger & Koo, 2005). High-tech startups have contributed to innovation, creation of jobs, and economic development in most of the developed economies, especially in the USA (Joshi & Achuthan, 2018). Besides the US (See Table 7.11 for Abbreviations), Canada in North America, European nations such as UK, Germany, France, Turkey; Asian economies like Israel, China, India, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and the Australian sub-continent have fast witnessed the rise of high-tech entrepreneurship.

The digital technology-related sector is exploding on a global scale, surpassing most other business segments over the past two decades and this development is steady and continuous. The high-tech industry turns out to be the most important growth sector for startups. In 2019, more than half of the startups across the globe belonged to the high-tech sector: Web services and apps (18.6%), Software as a service (15.3%), E-commerce (10.1%), and IT and Software (8.6%) (Source: https://valuer.ai/blog/top-50-best-startup-cities/, 2019).

There is a lot of interest generated in researching the factors that contribute to successful performance of high-tech startups and their growth and scalability to the next level. Amidst this backdrop, the current study tries to explore the role of three independent variables namely founders’ national culture values (section “Founders’ National Culture and Entrepreneurship” of this work), his transformational leadership traits (section “Founders’ Transformational Leadership Traits and Startup Performance”), and the startup culture developing from the type of funding received by the startup (section “Startup Culture Emanating from Source of Funding and Startup Performance”) on the dependent variable namely startup performance (section “Startup Performance”). This study uses a unique mix of three independent variables which have never been used together in previous researches. Therefore, this study would provide immense implications (section “Implications of the Study”) for researchers and practitioners in the fields of entrepreneurship, startup performance, national culture values, transformational leadership, and startup funding.

Founders’ National Culture and Entrepreneurship

Hayton, George, and Zahra (2002) reviewed and synthesized findings from 21 empirical studies to examine the association between national culture characteristics and entrepreneurship. It is widely believed that an individual’s engagement in entrepreneurial action is more consistent with some cultures than others. Potential entrepreneurs take into account not only their individual capabilities, skills, and probability of success but also how much starting a new venture is consistent with the culture dominating their society (Autio, Pathak, & Wennberg, 2013; Hechavarría, 2016). Let us now delve on the individual elements of national culture.

Elements of National Culture

Culture may be defined as a “collective mental programming distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from others” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 9). The elements that frame such mental programming are values that are transmitted throughout generations in a society, resulting in the formation of certain motivations, attitudes, and behavioral patterns. Hofstede’s classical research on dimensions of national culture, first recognized at the end of 1970s, was based on four attributes of national culture—individualism versus collectivism, large versus small power distance, strong versus weak uncertainty avoidance and masculinity versus femininity. Later research on cultural dimensions added a fifth perspective called Confucian Dynamism which was unique as compared to previous four dimensions and it was later named as long-term versus short-term orientation (Hofstede, 1991, 2001). In 2010, a sixth dimension was added to the model, indulgence versus restraint. This was based on Bulgarian sociologist Minkov’s label and also drew on the extensive World Values Survey to further study this latest dimension (Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M., 2010). These six elements and their impact on the founders’ intentions and actions to “start-up” are discussed below.

Individualism Versus Collectivism

The first dimension is labeled “Individualism versus Collectivism.” It depicts the relationship between an individual and his fellow individuals and society at large. This dimension ranges along a continuum of two extremes. At one end are individualist societies where relations between individuals are very loose to the extent that these individuals take care of their own and their immediate family’s interests only. At the other end are collectivist societies where relations between individuals are very tight. Individuals in such societies are parts of groups that include extended families, their tribes, villages, etc. Opinions and beliefs of individuals need to be in synchronization with those of the group and in turn, the group protects the individual in case of any trouble.

Individualistic traits such as need for personal achievement, self-efficacy, desire for independence, and the lower fear of failure may lead people to develop entrepreneurial intentions which could eventually make them startup founders. Perceived levels of self-efficacy are higher in individualist societies as compared to collectivist societies, and therefore, people from individualist societies are more likely to become entrepreneurs. As opposed to this, collectivist attributes such as the fear of “losing reputation” or family name through failure could discourage would-be entrepreneurs. High level of collectivism could reduce the entrepreneurial desirability and the motivation to seek self-employment (Bogatyreva, Edelman, Manolova, Osiyevskyy, & Shirokova, 2019).

Large Versus Small Power Distance

The second national culture dimension labeled as “Small versus Large Power Distance” is about how society deals with power inequality. Physical and intellectual capacities are unequally distributed among individuals in all societies. At one end are societies that allow these inequalities to grow over time into inequalities of power and wealth. These inequalities then become hereditary with no connection to physical and intellectual capacities. At the other end are societies that try to reduce inequalities in wealth and power as much as possible, though inequality cannot be eliminated completely. “This degree of inequality is measured by the Power Distance Scale, which ranges from 0 (small power distance) to 100 (large power distance) (Hofstede, 1983, p. 81).” Power distance in organizations relates to the degree of centralization of authority and the degree of autocratic leadership. Societies and organizations with inequality in power distribution satisfies the “psychological need for dependence of people without power (Hofstede, 1983, p. 81).”

In the large power distance societies, resources and information are concentrated in the domain of the powerful. As entrepreneurship and startup activities consume resources, the less powerful individuals of such societies may not be encouraged to take up entrepreneurship. Individuals in large power distance societies subconsciously perceive that the chances to succeed are unevenly distributed (Rusu, 2014). Therefore, they may not find the troubles of being a startup founder (entrepreneur) rewarding enough. In contrast, the small power distance societies would support the entrepreneurial inclinations. This is because the small power distance societies would support more independence and disregard the hierarchical relationships.

Strong Versus Weak Uncertainty Avoidance

The third dimension known as “Strong versus Weak Uncertainty Avoidance” deals with how individuals and society deal with uncertainty and the risks associated with it. At one end are societies whose members accept uncertainties without getting upset about them, individuals in such societies can take risks easily. Such societies are known as “weak Uncertainty Avoidance” societies. On the other end are societies that socialize its members in trying to beat the future, which results in anxiety and aggression for its members because of the unpredictable nature of the future. Such societies are known as “strong Uncertainty Avoidance” societies; these societies try to avoid risk and create security through technology, law, and religion.

Cultures characterized by weak uncertainty avoidance support openness to new ideas and achievement orientation (Bogatyreva et al., 2019; Braandstatter, 2011, Hayton et al., 2002). Individuals in such societies are not affected by uncertainties that are so common for the early startup activities and they are more likely to engage in action planning. As opposed to this, individuals in strong uncertainty avoidance societies would doubt entrepreneurial actions; given the uncertainty it is likely to involve.

Masculinity Versus Femininity

The fourth dimension known as “Masculinity versus Femininity” deals with the division of roles among males and females in a society. With the entire mankind divided into one half of males and one half of females, only procreation roles are strictly sex determined in the biological sense. However, all other roles are associated exclusively to either men or women in the social sense. Societies that make water-tight compartments of gender based roles and men take up significant and assertive roles whereas women take up more secondary and caring roles are known as masculine societies. Masculine societies consider achievements, money, and show-off as significant. On the other hand, societies that allow both the genders to take up a variety of roles, without being gender specific, are known as feminine societies. These societies consider relationships, helping others, and quality of life as significant (Hofstede, 1983).

Entrepreneurship is perceived as a masculine domain (Newbery, Lean, Moizer, & Haddoud, 2018) and therefore related to masculine traits such as need for independence, aggression, and courage. Therefore, entrepreneurs rate higher on masculine traits as compared to non-entrepreneurs (Bogatyreva et al., 2019). Individuals in societies possessing higher levels of masculinity traits are more likely to exploit opportunities and transform their ideas into viable startups. Individuals exposed to more masculine cultures, driven by the material rewards, are also likely to invest their efforts in search of profitable business opportunities that can generate incomes, as compared to the ones exposed to feminine cultures.

Long-Term Versus Short-Term Orientation

There was a later addition to Hofstede’s model of national culture values. This was derived from a research of students’ values in 23 countries of the world initiated by Michael Harris Bond. Originally known as “Confucian Work Dynamism,” it was incorporated as the fifth national cultural dimension and labeled as “Long-term versus Short-term Orientation.” Long-term orientation “stands for the fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards, in particular perseverance and thrift” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 359). On one end are individuals, and thus societies, that are focused on future and willing to forgo short-term material, success or gratification for the sake of the future; this is “Long-term Orientation.” On the other end are individuals and societies that are focused on past or present more than the future and value tradition, fulfillment of social obligations and immediate gratification; this is “Short-term Orientation.”

A long-term orientation supports the capitalist views and would, therefore, support entrepreneurial intentions of individuals. Entrepreneurship would entail substantial risks and may be rewarding in the long run only; therefore, individuals exposed to cultures with long-term orientation are more likely to take up entrepreneurship. Individuals from long-term oriented societies are also better prepared to wait for entrepreneurial rewards. In contrast, individuals belonging to short-term oriented societies are more likely to opt for employment in well-established organizations that provide stability and regular income.

Indulgence Versus Restraint

One challenge that confronts humanity, now and in the past, is the degree to which small children are socialized. Without socialization we do not become “human.” This dimension is defined as the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses, based on the way they were raised. Relatively weak control is called “Indulgence” and relatively strong control is called “Restraint.” Cultures can, therefore, be described as indulgent or restrained. Indulgence societies tend to allow relatively free gratification of natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun whereas Restraint societies are more likely to believe that such gratification needs to be curbed and regulated by strict norms. Indulgent cultures will tend to focus more on individual happiness and well-being, leisure time is more important and there is greater freedom and personal control. This is in contrast with restrained cultures where positive emotions are less freely expressed and happiness, freedom, and leisure are not given the same importance (Maclachlan, 2013).

This sixth dimension has not as yet been widely adopted within the intercultural training and management field and this may simply be because it is still relatively new. Indulgence versus restraint would also seem to have an impact on generational differences. The impact of technology on younger generations would suggest that the need for instant gratification is more prevalent but more research is still needed. Indulgent societies believe that they have control on their own life and emotions. They are more optimistic and oriented toward quality of life, while restrained ones are pessimistic and driven by the strong norms. It is expected that indulgent societies have more entrepreneurial orientation than the restrained ones (Jovanović, M., Miloš J., & Petković J., 2018).

How National Culture Can Be Measured at Individual Level

This study proposes that national culture values of startup founders will have a strong influence on the high-tech startup performance, which eventually boosts the growth and scalability prospects of the new venture. The cultural value variables as defined by Hofstede were meant to measure national culture. However, Yoo, Donthu, and Lenartowicz (2011) have developed and validated a scale for measuring Hofstede’s dimensions of national cultural values at the individual level. Startup entrepreneurs are individuals guided by the macro-influence of their national cultures. Therefore, CVSCALE, a 26-item five-dimensional scale of individual cultural values, developed by Yoo et al. (2011) can be used to measure the national culture values of startup founders, as depicted in Table 7.1. This scale does not include measurement items for the indulgence versus restraint factor for individual level study.

India and the National Culture Dimensions

This section is a discussion on where India stands for all six national culture dimensions (Hofstede Insights).

Individualism Versus Collectivism

India, with a rather intermediate score of 48, is a society with both collectivistic and individualist traits. The collectivist side means that there is a high preference for belonging to a larger social framework in which individuals are expected to act in accordance to the greater good of one’s defined in-group(s). In such situations, the actions of the individual are influenced by various concepts such as the opinion of one’s family, extended family, neighbors, work group and other such wider social networks that one has some affiliation toward. For a collectivist, to be rejected by one’s peers or to be thought lowly of by one’s extended and immediate in-groups, leaves him or her rudderless and with a sense of intense emptiness. The employer/employee relationship is one of expectations of—loyalty by the employee and almost familial protection by the employer. Hiring and promotion decisions are often made based on relationships which are the key to everything in a collectivist society.

The individualist aspect of Indian society is seen as a result of its dominant religion/philosophy—Hinduism. The Hindus believe in a cycle of death and rebirth, with the manner of each rebirth being dependent upon how the individual lived the preceding life. People are, therefore, individually responsible for the way they lead their lives and the impact it will have upon their rebirth. This focus on individualism interacts with the otherwise collectivist tendencies of the Indian society which leads to its intermediate score on this dimension.

Large Versus Small Power Distance

India scores high on this dimension, 77, indicating an appreciation for hierarchy and a top-down structure in society and organizations. If one were to encapsulate the Indian attitude, one could use the following words and phrases: dependent on the boss or the power holder for direction, acceptance of un-equal rights between the power-privileged and those who are lesser down in the pecking order, immediate superiors accessible but one layer above less so, paternalistic leader, management directs, gives reason/meaning to one’s work life and rewards in exchange for loyalty from employees. Real Power is centralized even though it may not appear to be and managers count on the obedience of their team members. Employees expect to be directed clearly as to their functions and what is expected of them. Control is familiar, even a psychological security, and attitude toward managers are formal even if one is on first name basis. Communication is top-down and directive in its style and often feedback which is negative is never offered up the ladder.

Strong Versus Weak Uncertainty Avoidance

India scores 40 on this dimension and thus has a medium low preference for avoiding uncertainty. In India, there is acceptance of imperfection; nothing has to be perfect nor has to go exactly as planned. India is traditionally a patient country where tolerance for the unexpected is high; even welcomed as a break from monotony. People generally do not feel driven and compelled to take action-initiatives and comfortably settle into established rolls and routines without questioning. Rules are often in place just to be circumvented and one relies on innovative methods to “bypass the system.” A word used often is “adjust” and means a wide range of things, from turning a blind eye to rules being flouted to finding a unique and inventive solution to a seemingly insurmountable problem. It is this attitude that is both the cause of misery and the most empowering aspect of the country. There is a saying that “nothing is impossible” in India, so long as one knows how to “adjust.”

Masculinity Versus Femininity

India scores 56 on this dimension and is thus considered a Masculine society. India is actually very Masculine in terms of visual display of success and power. The designer brand label, the flash and ostentation that goes with advertising one’s success, is widely practiced. However, India is also a spiritual country with millions of deities and various religious philosophies. It is also an ancient country with one of the longest surviving cultures which gives it ample lessons in the value of humility and abstinence. This often reigns in people from indulging in Masculine displays to the extent that they might be naturally inclined to. In more Masculine countries the focus is on success and achievements, validated by material gains; work is the center of one’s life and visible symbols of success in the work place are very important.

Long-Term Versus Short-Term Orientation

With an intermediate score of 51 in this dimension, a dominant preference in Indian culture cannot be determined. In India the concept of “karma” dominates religious and philosophical thought. Time is not linear, and thus is not as important as to western societies which typically score low on this dimension. Countries like India have a great tolerance for religious views from all over the world. Hinduism is often considered a philosophy more than even a religion, an amalgamation of ideas, views, practices and esoteric beliefs. In India there is an acceptance that there are many truths and often depends on the seeker. Societies that have a high score on pragmatism typically forgive a lack of punctuality, a changing game-plan based on changing reality and a general comfort with discovering the fated path as one goes along rather than playing to an exact plan.

Indulgence Versus Restraint

India receives a low score of 26 in this dimension, meaning that it is a culture of Restraint. Societies with a low score in this dimension have a tendency to cynicism and pessimism. Also, in contrast to indulgent societies, restrained societies do not put much emphasis on leisure time and control the gratification of their desires. People with this orientation have the perception that their actions are restrained by social norms and feel that indulging themselves is somewhat wrong.

Discussion on National Culture Variables and Indian High-Tech Entrepreneurship

It was reported in different studies—although their validity is still disputable—that high individualism and masculinity and low uncertainty avoidance and power distance as well as long-term orientation and indulgence pave the way for a better cultural environment for entrepreneurship. Assessments made on the basis of the cultural dimensions of Hofstede show that India’s score in the dimension of “Power Distance” is high while its scores in the dimensions of “Individualism” and “Masculinity” are low and that the Indian people refrain from “Uncertainty” as much as possible. Indians cannot be clearly depicted as long-term or short-term oriented and they are definitely high on Restraint. Graph 7.1, where the scores India gets in the dimensions of national culture are given in comparison with the USA and UK (that take place near the top in terms of entrepreneurship), clearly demonstrates the above-mentioned cultural structure of India.

India ranks 78th in a study of 137 countries for Global Entrepreneurship Index, 2019, whereas USA stands 1st and UK stands 5th. This study is based on 14 pillars that constitute the index namely opportunity perception, startup skills, risk acceptance, networking, cultural support, opportunity startup, technology absorption, human capital, competition, product innovation, process innovation, high growth, internationalization, and risk capital (Global Entrepreneurship Index, 2019). In spite of this, India added over 1,300 high-tech (internet) startups in 2019 and there were a total of 8,900–9,300 internet startups in India up till November 2019. India is also home to 30 unicorns—the third highest number of unicorns (companies with valuation of over $1 billion) in a single country in the world. These startups have created an estimated 60,000 direct jobs and 1.3–1.8 lakh indirect jobs (The Economic Times, 2019).

From the above discussion on India’s standing for Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and India’s ranking on Global Entrepreneurship Index, we can conclude that the relationship between national culture variables and entrepreneurship cannot be established exactly in India, given the growth statistics of internet startups. Entrepreneurship in general and internet entrepreneurship in specific has seen significant growth in India due to the following reasons (Nair, 2015; Rozani, 2019).

-

a.

Entrepreneurs can access the market through the internet and technology is a huge enabler to entrepreneurship in India.

-

b.

Risk taking appetite has increased significantly for students clearing the higher education institutes from India. They are ready to give time and energy to starting up rather than taking campus placements to earn a steady income.

-

c.

A lot of students from tier-3 and tier-4 cities are joining premier higher education in India. They know a lot of problems at the grassroots level and this gives rise to social entrepreneurship.

-

d.

The availability of seed funds, angel funds, crowdfunding, and venture financing has made it easier to startup in India, in the last decade.

-

e.

Technology also enables ease of communication for the various stakeholders in a startup and this can make the process quick and cost-effective.

-

f.

With stringent financial regulations in India, the financial system is more transparent and conducive to new businesses.

-

g.

A number of business management and engineering schools in India have started innovation and incubation centers to benefit their students who have startup ideas. These centers provide mentoring, technical, regulatory and financial support to budding entrepreneurs.

-

h.

Though nascent, there is a vibrant ecosystem which is supportive of entrepreneurship. There are companies that can loan office space, furniture, etc. So even if someone has nothing but an idea, he can still startup as the ecosystem is very supportive.

-

i.

There are considerable numbers of failed startups in the Indian startup ecosystem. However, there are institutions and others who are willing to give people a second chance. The number of people willing to give up steady, well-paying jobs to get into entrepreneurship has risen in this millennium. There is no stigma about failures in the startup ecosystem.

-

j.

The “Startup India” movement by the Indian government has made a huge impact on the country’s industrial sector, leading to a large number of digital startups blossoming in the country, making it the hub for new IT ventures. Besides this, NITI Aayog is in the process of making the necessary infrastructure and resources available through the Atal Innovation Mission (AIM).

-

k.

With the easy availability of high-speed internet and various tools in the market, digital literacy is on a constant rise in India, allowing a huge number of people to become digitally savvy and equipping themselves with the required skills. This definitely provides an edge to internet entrepreneurship in India.

Founders’ Transformational Leadership Traits and Startup Performance

Startups fail as much due to lack of entrepreneurial skills and managerial incompetency for project planning and execution as intense competition, rapidly developing technology, uncertainty, faulty time to market, funding, etc., among others. Startups may be relatively low on assets and/or resources but can definitely compensate by using leader’s capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation (Joshi & Achuthan, 2018). As India develops into a fast growing hub of high-tech startups, the significance of leadership cannot be undermined for the establishment, growth, and scalability of startups. Three most important challenges for startup founders include developing a vision, achieving optimal persistence, and executing through chaos (Freeman & Siegfried, 2015).

Transformational leadership is one of the most widely studied constructs in the leadership domain. It has been credited with “influencing followers by broadening and elevating followers’ goals and providing them with confidence to perform beyond the expectations specified in the implicit or explicit exchange agreement.” Researchers have found that transformational leadership can be particularly effective during times of extreme challenge or crisis (Kang, Solomon, & Choi, 2015; Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013). Zaech and Baldegger (2017) conclude that transformational leadership behavior of founder-CEOs will be positively related to startup performance, whereas transactional and laissez-faire leadership behavior of founder-CEOs will be negatively related to startup performance.

In the beginning of firm development, the founder-CEOs show relatively more facets of transformational leadership behavior (Baldegger & Gast, 2016). A founder-CEO must create a vision for the startup and influence others to follow their dreams in order to attract employees and acquire necessary resources for developing their new ventures. The vision presents an orientation guide for the employees which can be modified conjointly. Furthermore, startups operate in an open context, which can be characterized by rarely developed structures, occasional processes and a flexible, external-oriented culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). This explains the need for transformational leadership on the part of startup founder for initial success of the startup (Zaech & Baldegger, 2017). Therefore, this study proposes that transformational leadership traits of the founder-leaders will have a strong influence on the high-tech startup performance, which eventually boosts the growth and scalability prospects of the new venture. We will now delve into the various transformational leadership traits.

Transformational Leadership Traits

In the case of transformational leadership, culture is especially significant because leaders will not be able to understand the true needs of followers if they do not understand their values, norms, and beliefs. Therefore, this study focuses on the six traits of Transformational Leaders; as developed and validated by Singh and Krishnan (2007); which are discussed in the following section.

“Performance Oriented and Humane” Trait

“Performance-oriented and Humane” trait highlights the attitudes that leaders (startup founders) have in approaching their tasks. The leader’s focused dedication to his or her work at hand inspires the followers to do the same. This factor also highlights the approach used by the leaders toward others’ tasks. A startup founder who guides and presides over groups’ tasks, instead of complete delegation without no monitoring at all, is likely to steer the startup performance through his leadership traits.

“Openness and Nurturing” Trait

The second trait “Openness and Nurturing” indicates that transformational leadership involves trusting the followers and encouraging them to work independently. Followers expect their managers to empower them. Several previous studies presented patterns of transformational leadership styles in Indian firms and showed that such leaders had an empowering attitude towards their followers.

“Sensitive and Conscientious” Trait

The third trait “Sensitive and Conscientious” indicates a high degree of sincerity and seriousness of the startup founder towards other members of the team. This aspect has been highlighted by several studies on leadership and is also a cross-cultural phenomenon.

“Personal Touch” Trait

The fourth trait “Personal Touch” has been reported by many studies on Indian leaders. Indians are said to be high on need for personalized relationships (Kakar, Kakar, Vries, M.F.R. & Vrignaud, 2002; Sinha, 2000: 19). This factor shows that transformational leadership in India involves the founder-leader taking an interest in the whole person; that is, in both personal and official aspects of the team member’s life. This trait will have a significant positive impact on the performance of the startup and the contextual performance of the startup team.

“Conviction in Self” Trait

The fifth trait “Conviction in Self” indicates self-confidence as well as confidence of the startup founder in the vision he or she is promoting. This is a universal dimension and has been highlighted in many studies (Kanungo & Misra, 2004). This is probably where the role-modeling effect of the leader also comes into play.

“Non-Traditional” Trait

The sixth trait “Non-traditional” highlights the leader’s ability of openness to change. They are not just open to new ideas and ways of doing things; they also help their subordinates adopt such strategies. This trait also includes the startup founder’s being open to re-interpreting organizational rules and regulations for the sake of a noble objective. They encourage followers to break away from past practices, the status quo, and socially determined hang-ups.

How Transformational Leadership Traits Can Be Measured at Individual Level

Singh and Krishnan (2007) developed and validated a 27 item scale for measuring transformational leadership traits in the Indian context. It used the above discussed six traits. Table 7.2 discusses the individual measurement items for each trait in detail.

Indian Internet Entrepreneurship Case Studies Based on Transformational Leadership Traits

There are a lot of cases that we can discuss in the relevance of these individual traits of transformational leadership in the Indian context. Although a leader could portray several/all of these traits in some or the other situation, the author highlights the most significant transformational leadership trait of each of these high-tech startup founder/CEO in India. These six cases are largely based on information provided by Nishtha Tripathi in her book “No Shortcuts: Rare Insights from 15 SUCCESSFUL Start-up Founders” which is based on her first-hand interviews with 15 select startup entrepreneurs in India (Tripathi, 2018). Each case begins with brief information of the startup, followed by a table that discusses key takeaways about the specific transformational leadership trait displayed by the startup founder(s).

Performance Oriented and Humane Trait: Case of Ather Energy

Ather Energy is a hardware startup founded by IIT Chennai alumni Tarun Mehta and Swapnil Jain in 2013. The founders were convinced that there was an opportunity to build an electric vehicle in India that could match petrol scooter on the specs. Initially funded by Department of Science and Technology at IIT Chennai, Srini V Srinivasan (IIT Chennai alumnus and founder of Aerospike) and Sachin and Binny Bansal (founders of Flipkart Inc.) and later funded by Tiger Global, Hero MotoCorp, Sachin Bansal, and Innoven Capital, Ather Energy is into designing and manufacturing electric vehicles in India. Ather Energy manufactures Ather 450, an electric two-wheeler with multi-dimensional features relating to body, battery, monitor, speed, lighting, and smart connectivity. It also establishes Ather Grid, an electric charging infrastructure in cities that it is present in. The company has announced online-only purchase model for selling its electric vehicles, with doorstep service. Unlike most auto manufacturers in India, Ather Energy owns and operates its own Experience Centres. The company claims that this helps in maintaining end-to-end customer experience. The Experience Centres, dubbed AtherSpace, are aimed at increasing product understanding, providing customer education, and giving a first-hand experience of the product to consumers. Ather Energy set up its manufacturing unit at Whitefield, Bengaluru, in 2018 with a capacity to make 600 units per week. In December 2019, Ather Energy signed an MoU with Government of Tamil Nadu to set up a manufacturing plant in Hosur, Tamil Nadu (Mukherjee, 2020; Tripathi, 2018). Table 7.3 provides insights into leadership traits of Ather Energy founders.

Openness and Nurturing Trait: Case of Freshdesk (Now Freshworks)

In March 2010, a bad experience with customer service team for a broken television led Zoho Corp executive Girish Mathrubootham and his colleague Shan Krishnasamy to design a helpdesk software loaded with features that mattered from years of product experience at Zoho. The idea of Freshdesk was officially incorporated a few months later, in Chennai, India. With initial funding from venture capital firm Accel and later funding from Tiger Global and Accel, Freshdesk crossed the 30,000 customer mark in 2014. In August 2015, Freshdesk announced its first acquisition—video chat and co-browsing platform 1CLICK.io. The very next year, Freshdesk launched a CRM platform called Freshsales. In June 2017, Freshdesk Inc. rebranded to Freshworks Inc. to reflect its evolution as a products platform. In July 2018, Freshworks was the first SaaS unicorn from India; backed by fresh investments from Accel, Sequoia Capital India and CapitalG. In 2020, with multiple products such as Freshworks 360 (Customer Engagement Suite), Freshchat (Customer Messaging Software), Freshmarketer (Marketing Automation Platform), Freshrelease (Project Management Software), Freshteam (Human Resources Software) and Freddy (an AI engine), Freshworks has more than 1,50,000 customers across the world (Chanchani, 2019; Tripathi, 2018). Table 7.4 provides the key leadership features of Freshworks founders.

Sensitive and Conscientious Trait: Case of Aspiring Minds

Varun Aggarwal, the founder of Aspiring Minds, was a student at NSIT, Delhi and later at MIT. At MIT, he got interested in social issues, studied socioeconomic situations in India and got interested in a report by McKinsey that only 25% engineers are employable in India. He was joined by his brother Himanshu, who was more of a technical person. With mentoring from Tarun Khanna of Harvard Business School, Aspiring Minds was started in 2008 to target the two-way problem: one, companies not getting quality candidates and two, good candidates not being able to showcase their skills. They designed tests around English, logical ability and quantitative ability: skills that are important in a wide variety of jobs. They named their test as AMCAT and the initial batch of students that took the test were highly satisfied with what Aspiring Minds provided to them as test result and feedback.

Beating the teething troubles that were escalated by the 2008 recession, Aspiring Minds went on from being bootstrapped to funded first by Ajit Khimji group. With the right fundraising, hiring and sales strategies, Aspiring Minds achieved significant growth. It undertakes cognitive ability, personality, technology, and job simulation tests for its clients. It also provides pre-employment testing, qualified talent sourcing and campus hiring, among others, for its over 3,000 clienteles, spread across industries, and includes IT, banking and financial services, manufacturing, healthcare and life sciences, retail and education. Besides India, Aspiring Minds scaled rapidly to the US, China, Philippines, and Middle East. Online retail major Amazon, mobile operator Airtel, IT company Wipro, as well as Chinese internet search major Baidu, telecommunications giant Verizon and US industrial conglomerate Honeywell are its clients; to name a few. In October 2019, US-based talent evaluation leader SHL has acquired Aspiring Minds, in a largely all-cash deal worth $ 80–100 million (Gooptu, 2019; Mansur, 2019; Tripathi, 2018). Table 7.5 discusses significant leadership traits of Aspiring Minds founders.

Personal Touch Trait: Case of Unacademy

Unacademy kicked off as a YouTube channel in 2010, when Gaurav Munjal explained a concept in computer science subject to his friends over a video. He was joined by his friend Roman Saini who was a doctor from AIIMS and had also cleared Civil Services Examination in 2014 in first attempt. When Roman gave UPSC preparation courses on Unacademy, it received a million views within a month. This gave them the idea of building a tool that will allow anyone to start teaching. They were joined by the third co-founder Hemesh Singh, the person whose brain designed the product at Gaurav’s previous startup—Flatchat and the fourth one, Sachin Gupta. Thus Unacademy started in a new form in August 2015.

Unacademy created an educator app and a learner app that can run on any simple smartphone, even in remote locations with network issues. The educator app was launched in May 2017, through which several candidates, even those who were successful from backward villages of India, created content that would help thousands of aspiring others. Beginning from May 2016 and up to February 2020, Unacademy has raised $ 198.5 Million in seven rounds of funding from investors like Facebook, General Atlantic, Sequoia Capital India, Steadview Capital, Blume Ventures, Nexus Venture Partners, etc. With more than 10,000 educators, over 100 million video views a month, 4,00,000 daily active users and celebrity educators such as Dr. Kiran Bedi and Dr. Shashi Tharoor, Unacademy founders have a mission to make it the world’s largest online education platform (Malik, 2019; Tripathi, 2018). Table 7.6 provides a snapshot of leadership characteristics of Unacademy founders.

Conviction in Self Trait: Case of Wingify

Wingify founder Paras Chopra was a student of biotechnology at the Delhi College of Engineering. After four failed attempts at starting up, he was fascinated by marketing. He decided to write a software for marketing and after trials and errors, in 2009, he designed a Visual Website Optimizer (VWO) that was a simple, low cost and more usable alternative to Google Website Optimizer. Thus, Wingify was founded and headquartered in New Delhi. In 2010, as active users for his product increased, he made it paid. With value-based pricing, growth through content marketing, and diligent team-building efforts, Wingify is in the business of Customer Experience Optimisation with products such as VWO Testing (an A/B, Split, and Multivariate Testing solution), VWO Engage (a push notification service for web and mobile, VWO Insights (a visitor behavior tracking & analytics product), VWO FullStack (a server side testing solution) and VWO Plan (a program management layer for experience optimization), etc. In 2017, Wingify grew to amass 6,000 paid clients for its two products VWO Testing and VWO Engage in about 90 + countries and hit an envious annual revenue of $18 million, which grew to approximately $20 million by 2019 (Modgil, 2017; Tripathi, 2018). Table 7.7 discusses the leadership traits of Wingify founder.

Non-Traditional Trait: Case of Faasos

Jaydeep Barman and Kallol Banerjee, two food loving Bengalis who craved for good old Calcutta roles, bought a cook from Kolkata and hired a space to start their first Faasos kitchen in Pune in 2004. After breaking even in 2005, both of them headed for MBA at INSEAD. Post-MBA, Jaydeep joined McKinsey, London and Kallol joined Bosch, Singapore. Faasos was handled by their friends for a 50 percent stake. In 2010, on a sabbatical from work, Jaydeep handled Faasos once again and decided to commit fully to it, along with Kallol. Faasos raised its first round of funding worth $5 million from Sequoia Capital in 2012.

During this time, Jaydeep Barman took many significant decisions like focusing on delivery, starting a website and taking only online orders, hiring industry veterans to run the show, venturing into Mumbai, etc. Some decisions were very efficient and others were disastrous. However, Faasos continued to grow. The company launched its mobile app in March 2014. The app launch increased the number of orders, and 80% of the orders were coming from the app only. The app was easy to use, and thus, the owners decided to turn their service into app-only service. Till date, Rebel foods, the parent company of Faasos has received $125 millions of funding, largely from Sequoia Capital India, Lightbox Ventures, Goldman Sachs, and ru-Net South Asia. It operates 235 kitchens across 20 Indian cities (Tripathi, 2018; Vashishtha, 2019). Table 7.8 provides key leadership insights of Faasos founders.

These six case studies highlight the significance of transformational leadership traits among startup founders—for gaining traction in the highly competitive internet startup arena in India.

Startup Culture Emanating from Source of Funding and Startup Performance

There are three primary funding mechanisms for high-tech startups:

-

i.

Self-funding from the entrepreneur’s personal resources and “friends and family”

-

ii.

Funding from venture capital firms

-

iii.

Funding from larger corporate and governmental agencies.

Each different funding source potentially impacts the startup culture and strategy execution (Hamilton, 2001). Given the importance of corporate culture in strategy execution, it becomes very significant that what kind of culture high-tech startups create by how they acquire their financial resources. Therefore, this study proposes that startup culture emanating from the funding source will exert a strong influence on the high-tech startup performance, which eventually boosts the growth and scalability prospects of the new venture. We will now delve into the effects of each funding source on the initial startup culture.

Self-Funding from Entrepreneur’s Personal Resources, “Friends and Family” and Startup Culture

Self-funded startups are created out of a particular entrepreneur’s vision, and serves a need where that entrepreneur has skills and resources. This is popularly known as “bootstrapping” and funds and initial requirements for startup are collected through entrepreneur’s credit card payments, mortgaging his personal assets, using his retirement funds and/or chipping of sizeable cash by family members and close friends. If this startup firm starts growing, it may use equipment-leasing or bank loan or factoring as a secondary source of funding.

The most significant priority of a self-funded firm is increasing revenue; since it may cease to exist without sales growth. These firms cut costs and try to ensure profitable sales. Since a bunch of quality personnel would be very significant for the startup team at this stage, they need to be attracted and retained with reasonable salaries. Therefore, cost cutting can be done through using a non-prime location for office, second-hand furniture and equipment at office and delaying investment of time, resources and personnel in a future-oriented activity like knowledge creation (Hamilton, 2001).

There are several positive aspects of self-funded high-tech startups. The atmosphere at such startups would be relaxed and personal needs of the small team are taken into consideration, making it a culture of “all being together in the venture.” Such firms would take care of interests of all stakeholders such as customers, employees, suppliers. The entrepreneur relies on relationship building to seek guidance and help in case of future requirements. However, on the flip side, lack of funds can hamper growth of a self-funded startup and it may not have the resources to keep up with changes in the market. The biggest threat to the self-funded firm’s culture is the hostile external environment which includes competitors, the economy, changes in technology, regulations, etc. especially since the self-funded startup has no “back up” plan.

The Indian Context

The picture of self-funded startups is no different in India. Unlike the first generation entrepreneurs, today, the Indian startups may not feel the lack of sources of finance—VCs, angel investors, government funds, and even debt funds, banks, and NBFCs are also at their disposal. But times are changing and new age startups are looking to play this the old school way. Startups have realized that—“equity money is not free money.” While, today, still a large number of startups remain dependent on external funding for survival and growth, there are set examples of founders who still believe in maintaining a complete stake in the company and grow organically for survival, and thus they go the bootstrapped way.

Bootstrapping gives the founders the freedom to put forth their own choices, even in bad times; to fall, learn from the mistakes and rise again taking their own time; and to expand their venture ahead on their own terms and timeline. We have examples of companies like Wingify, FusionCharts, Zerodha, Appointy, etc. who have gone the bootstrap way and achieved great heights (Agarwal, 2019).

Funding from Venture Capital Firms and Startup Culture

An increasing number of high-tech startups are being financed by venture capital at some or the other stage. However, a firm that is self-funded for years before seeking venture capital help may be able to sustain its self-funded culture. On the other hand, a firm that seeks venture capital funding very early in its history will be more susceptible to the venture capital-type culture (Garg & Shivam, 2017). Startups funded by venture capital are most likely to focus on “valuation” rather than “sales.” The focus on valuation makes venture financers subjective which means including their known names in the key management team of startup, fitting the startup into the latest “trend” of successful startups or even focusing on advertising and PR policies rather than selling the product.

Employees in venture-funded startups focus on “stock options” especially if they perceive the startup to be “close to IPO.” The most significant stakeholders in such startups are potential funding sources, sometimes even at the risk of ignoring customers and suppliers. The focus on valuations makes the situation very complex since valuations are a “zero-sum game.” Focus on valuations may generate inherent conflicts between startup founders, employees, and financers for personal financial gains. This develops a culture of depicting “all is well” to the outside world and even to the employees in a bid to keep the valuations at the highest possible level. Employees expecting windfall gains from stock options may suffer from sudden layoffs instead.

However, all is not wrong with the venture financed startups. The most positive aspect of a venture capital funded startup is that they have sufficient resources for the firm to grow fast; at least as long as the startup continues to meet the venture financers’ criteria. As opposed to the self-funded startups, venture-funded startups can keep pace with changes in the market place and gain significant competitive positioning in the minds of customers.

The Indian Context

Venture Capital funding for high-tech startups in India has witnessed three distinct phases:

-

Between 2011 and 2015, the industry experienced rapid activity growth (albeit off a small base) to support an evolving startup environment. During this phase, multiple VCs entered and became active participants in India’s economy for the first time.

-

This initial, almost euphoric, phase was then followed by moderation between 2015 and 2017. The lack of clarity regarding exits made investors more cautious, and that shifted the focus to fewer and higher-quality investments.

-

Since 2017, however, the VC industry in India has been in a renewed growth phase, buoyed by marquee exits for investors, such as Flipkart, MakeMyTrip, and Oyo; strong startup activity in new sectors, such as fintech and SaaS; and market depth in e-commerce.

Between 2012 and 2019, the number of startups in India increased by 17% each year, while funded startups’ compound annual growth rate increased faster at 19% during the same period. India’s unicorn tribe also continues to grow, with several firms in e-commerce, SaaS and fintech leading the way. About 80% of VC investments in 2019 were concentrated in four sectors: consumer tech, software/SaaS, fintech, and business-to-business commerce and tech. Consumer tech continues to be the largest sector, accounting for approximately 35% of total investments, with several scale deals exceeding $150 million. Within consumer tech, verticalized e-commerce companies continued to be the largest sub-segment, but in addition, there were increased investments in healthcare tech, food tech, and education tech. Both SaaS and fintech attracted significant investor interest and activity throughout 2019, with several early-stage and increasingly late-stage deals (Sheth, Krishnan, & Samyukktha, 2020)

Tiger Global, SoftBank, Naspers, Accel Partners, Sequoia Capital, Kalaari Capital, Blume Ventures, and many more venture capital financers have boosted the high-tech startups in India with several funding rounds. While success and growth stories of high-tech startups funded by venture financers in India are abuzz with names such as Flipkart, Paytm, Ola, Cardekho, Urban Ladder, Zomato, Swiggy, Big Basket, Quikr, InMobi, Mu Sigma, Oyo Rooms, BYJU’S, Udaan, Pine Labs, Lenskart, Dream11 (most names in this list are unicorns) there are venture-funded startups that have failed too. Housing.com, Stayzilla, Peppertap, Yumist, Fenomena, Cardback, and many more failed due to reasons attributable directly or indirectly to venture capital financing and the strain it brought on the startup operations and its core team.

Funding from Large Corporates/Governmental Agencies and Startup Culture

Large corporations have been one significant source of funding for startups. There are three specific reasons for this: One, well-established corporations have had ample cash and a rising stock market also supported their liquidity. Two, larger companies were seeing dearth of growth opportunities in their core lines of business and startups were being visualized as high-growth prospects. Three, corporates could be interested in the particular technology that a given startup is developing; and therefore, it receives funding from the larger companies.

The basic principle behind funding corporate-backed startups is that the technology or business model that the startup companies are developing is somewhat outside the scope of the larger corporation’s intended resource allocations and core competencies, but related to the overall strategic direction of the firm. For most corporate-funded ventures, the focus is on strategic germination. The daily orientation of the corporate-funded firm is on technical issues or developing technical excellence, that fit strategically with the sponsoring corporation as well as with key customers and industries.

The routine orientation of a corporate-funded startup is on developing technical excellence of a specific nature, and therefore, engineers could be more significant than the financial or marketing team (which is just not the case in the culture of startups which are self-funded or venture capital funded). The focus of corporates is on future technological breakthrough; unlike the venture financers where the focus is on future liquidity events. Therefore, there is a culture of “patience” in such startups. The startup also gets the advantage of high brand visibility and high brand equity that the well-established corporate brand is enjoying. The biggest potential issue with corporate-funded startups is the time taken in decision-making. High-tech startups function in an environment of fast technological changes and the speed of technological change is not in tandem with the speed of decision-making in an environment of corporate bureaucracy. Unless the corporate top management is directly interested in what the startup is developing, there may be great differences in corporate style, knowledge, and priority between the startup and the funding organization.

Governments across the globe are also trying to promote the startup ecosystem by providing policy reforms and financial grants to high-tech startups. There are several advantages of funding from government/government agencies. If a given startup falls within government priorities, it will get good money. Again, the government is not looking for direct returns on their money, and therefore, the pressure on the founder would be less. However, governments have some very specific criteria for funding and startups that don’t fall within those criteria, based on products/services and/or location, may not be granted any funding. It could be mandatory for government-funded startups to engage in say, R&D, hire people and generate employment or they may lose the funding or tax incentives related to funding. Also, government funding may be generated after a great deal of time and energy is spent on dealing with government bureaucracy with a lot of patience, and all startup founders may not be able to do it (borndigital, 2016).

The Indian Context

Infosys Innovation Fund, Wipro Ventures, TCS Coin, Microsoft Ventures (India), and many more are established by large Indian corporates to fund and mentor high-tech startups in India. Corporate accelerators are a particular type of seed accelerator, sponsored by a profitable company. TLabs, Z Nation Lab, BusinessWorld Accelerate, Nasscom Initiative, Venture Nursery, Microsoft ScaleUp, Cisco Launchpad, Google Launchpad, etc. are examples in this category. Apart from this, there are many education-sector backed accelerators and incubators such as Technology Business Incubator—FITT (IIT-Delhi), EDUGILD (MIT-Pune), CIIE (IIM-Ahmedabad), and others.

The government of India proposes to introduce a slew of reforms and funds to boost startups that are focussed on priority areas such as rural health care, water and waste management, clean energy solutions, cyber security, and drones. The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) plans to set up an India Startup Fund with an initial amount of Rs. 1,000 crores (Suneja, 2019).

Table 7.9 summarizes the key elements of above discussion depicting the effect of source of funding on the culture of the startup.

Startup Performance

The act of launching a new venture or a startup is perceived as an authentic and intrinsically motivated undertaking by an individual or, in most cases, a team of founders. Researchers have increasingly argued, for example, that founding teams create new ventures as a pathway to live a life consistent with their values and beliefs (Hmieleski, Cole, & Baron, 2012). Founder’s values and beliefs are strongly associated to the culture variables of the nation he/they belong to. Founder’s national culture variables, his transformational leadership traits and the culture emanating from the source of startup funding—all these three independent are likely to have a strong impact on the dependent variable in this study—startup performance.

Startup Performance Parameters

In the context of startups, sales growth is often used as the only performance indicator, which would provide an incomplete picture of startup performance. Therefore, the current study tries to supplement sales revenue growth with other internal behavioral aspects such as employment growth (Hmieleski et al., 2012), trust, commitment of the founding team members, (Wu, Wang, Tseng, & Wu, 2008), work satisfaction of the startup team members (Jensen & Luthans, 2006) and external aspects such as customer connects. Let us now delve into the individual elements that make the dependent variable namely startup performance.

Revenue Growth and Employment Growth

The most significant metrics of a startup performance would be measuring their revenue and employment growth. This data is available as year-on-year basis through several government and industry portals. Revenue growth and employment growth have been used in several past studies for analyzing new venture performance (Hmieleski & Ensley, 2007; Hmieleski, Cole & Baron, 2012; Jensen & Luthans; 2006; Wu et al., 2008; Zaech & Baldegger, 2017).

Trust

The foundation of trust between entrepreneurs and core members of the founding teams is normally based on previous relationship and affection between them. Founding team members take greater risk as compared to traditional industries because the industry environment is more unstable. That is, their investment is under higher vulnerability. Therefore, it is important for an entrepreneur to use his personal network to invite founding team members to join in the startup, because trust in the personal network can make them feel safer, and thereby more willing to contribute to the startup. That is, the strong ties/friendships that the founding team partners have with the entrepreneur make them to trust the entrepreneur, join the new venture and devote most of their resources, abilities, and time to the entrepreneur and new venture (Wu et al., 2008). Therefore, trust has a significant contribution to startup performance in the initial stage.

Commitment of the Founding Team Members

In accordance with the theory of the trust and commitment, we consider trust as a precursor of commitment. Because commitment involves potential vulnerability and sacrifice, it follows that people are unlikely to be committed unless trust is already established. Commitment of the core team to the founder’s vision comes for one more reason. Founding team partners hope that, by cooperating with the entrepreneur, they will be able to receive substantial economic rewards in the future. Owing to commitments, founding team partners are willing to not only provide resources and abilities but also have confidence about the positive future of startups, which is necessary for the startup to thrive (Wu et al., 2008). Thus, one can conclude that commitment of the core team to the entrepreneur’s startup is a pre-requisite to startup performance.

Work Satisfaction of the Startup Team Members

The drawbacks of working in a high-tech startup, and any startup, are generally related to short-term risks. Pay isn’t generally as good early on, benefits are limited until there are more employees, and the work life balance can be tenuous. There is a lack of structure in a startup, which has an impact on work hours, processes, and working relationships. Since teams are small, people generally have to wear a number of different hats, which can mean odd hours, late nights, and working on weekends. The long hours and huge workloads don’t necessarily mean a huge payout, either. Startups are working to get funding, which means money is often tight, and they can’t afford to pay employees the same high salaries as well-established corporates. Although there are a number of downsides to pay and benefits with startups, team members might reap the rewards of success if the company does well. Therefore, it becomes immensely important for the founder-leader to ensure work satisfaction of the team members (Jensen & Luthans, 2006). Startup team, type of work, pay, opportunities for growth, and supervision constitute the most significant elements of work satisfaction for startup team.

Customer Connectivity

“Customer is King” has been long acknowledged in the business world. All businesses bow to the chance they get to serve their target customer. Fulfilling the customers’ needs and getting a chance to serve them again is the ultimate pat on the back for a business, especially a startup. Through customer connectivity, it is not only the growth in sales revenue; but customers provide tangible suggestions and solutions also. It helps in customer retention, word of mouth referral sales, increasing team morale, and building brand image (Shenoy, 2019).

Lerner (2017) suggested measurement of customer connectivity for online businesses in his book, “Explosive Growth – A Few Things I Learned Growing to 100 Million Users and Losing $78 Million.” He concludes three metrics that matter for customer connectivity in internet businesses:

-

Whether or not a Unique Selling Proposition (USP) exists?

-

What Your Net Promoter Score (NPS) is?

-

Do You Have High User Retention?

How Can Startup Performance Be Measured

Having discussed the various startup performance parameters, Table 7.10 provides details of proposed measurement items and source for each parameter.

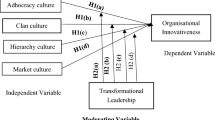

Section “Founders’ National Culture and Entrepreneurship” of this work discusses founder’s national culture variables and its impact on “starting up,” section “Founders’ Transformational Leadership Traits and Startup Performance” discusses founder’s transformational leadership traits and how they impact startup performance, section “Startup Culture Emanating from Source of Funding and Startup Performance” discusses the various funding methods for startups and how different funding methods create different cultures at startups. Finally, section “Startup Performance” discusses the parameters to measure startup performance. This study proposes that three independent variables discussed in sections “Founders’ National Culture and Entrepreneurship”, “Founders’ Transformational Leadership Traits and Startup Performance”, and “Startup Culture Emanating from Source of Funding and Startup Performance” impact startup performance. Figure 7.1 summarizes all the previous discussion in the form of a picture depicting the proposed relationships. This is followed by implications of this study.

Implications of the Study

As Fig. 7.1 suggests, this study uses three unique independent variables, that have never been used together previously, to understand their impact on the dependent variable startup performance. Startups and especially internet startups have contributed to entrepreneurship, business growth, creation of employment and wealth, not only in the developed but also the developing nations. Given the high failure rate of startups across the globe, a study on factors affecting startup performance has immense implications for researchers in the field of entrepreneurship, national culture, transformational leadership, startup funding, and startup performance. This study has implications for policy makers such as government and industry regulatory bodies as well as current and prospective entrepreneurs in the world of internet entrepreneurship. This study proposes a comprehensive model of antecedents of startup performance. It adds to the vast literature of startup performance by proposing a unique model. Policy makers and entrepreneurs would be perennially interested in factors impacting startup performance.

Scope for further research from this work can be discussed from several aspects.

-

1.

First, this study proposes relationships that need empirical testing. For national culture values, transformational leadership traits and startup performance, measurement items have been discussed in detail in Tables 7.1, 7.2, and 7.10, respectively. Using those measurement items, a primary survey of the current and prospective internet entrepreneurs (for their national culture values using Table 7.1), of their core team (for transformational leadership using Table 7.2 and for trust, commitment and work satisfaction parameters of startup performance using Table 7.10) and of customers (for customer connectivity parameter of startup performance using Table 7.10) can be undertaken. A self-report system using a five-point Likert scale can help collect primary data. Statistical tools such as analysis of variance, t-test, and structural equation modeling can be applied to the collected data for detailed analysis. For the relationship between startup funding and performance, interviews can be conducted with entrepreneurs, government funding bodies, and venture financers. Thus, the proposed model can be tested through primary data collection.

-

2.

Second, in the long run, experimental research and longitudinal studies could be undertaken to track changes in national culture values, transformational leadership traits and startup funding modes and check their impact on startup performance.

-

3.

Third, there can be a study of interplay between the various national culture variables. E.g., the entrepreneur’s long-term versus short-term orientation and his indulgence versus restraint characteristic may be related to each other.

-

4.

Fourth, transformational leadership traits may also evolve with time and startups may be funded through new and unique ways in future. These changes can have different impact on startup performance and this calls for new research in future.

-

5.

Fifth, all the national culture variables and all transformational leadership traits may not exert the same degree of influence on startup performance. It would be significant to study the relative influence of these sub-variables on startup performance.

-

6.

Sixth, this study uses trust, commitment of core members, their work satisfaction and customer connectivity as measures of startup performance. Future studies can check if these are direct measures of startup performance or are they moderating variables.

-

7.

Seventh, more moderating variables can be added to this study, such as age, gender, education of the entrepreneur, size of the startup etc.

Conclusion

This study provides a unique and comprehensive model of factors impacting startup performance. As the world faces unprecedented changes such as the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020, businesses face more volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. In a sense, COVID-19 has changed the way in which the world works, shops, communicates, relaxes, and entertains. Digital adoption continues to rise and it will be a tipping point for internet businesses. Therefore, internet startups are need of the hour and they will continue to be born and will be growing and evolving all the more. In such a new world, studies on factors that impact internet startup performances will be significant.

References

Agarwal, M. (2019). 11 Indian startups who are successful the bootstrapped way. Retrieved from https://inc42.com/features/11-indian-startups-who-are-successful-the-bootstrapped-way/.

Autio, E., Pathak, S., & Wennberg, K. (2013). Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviors. Journal of International Business Studies, 44 (4), 334–362.

Baldegger, U., & Gast, J. (2016). On the emergence of leadership in new ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(6), 933–957.

Blank, S. G., & Dorf, B. (2012). The start-up owner’s manual: The step-by-step guide to building a great company. Pescadero, CA: K&S Ranch Inc.

Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., Osiyevskyy, O., & Shirokova, G. (2019). When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96, 309–321.

borndigital. (2016). Which type of financing is right for your startup? The pros and cons of government funding. Retrieved from https://www.borndigital.com/2016/08/19/startup-financing-government-pros-cons.

Braandstatter, H. (2011). Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(3), 222–230.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2005). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. Hoboken: Wiley.

Chanchani, M. (2019, October 17). Freshworks eyes funding round at $3 billion valuation. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/freshworks-eyes-funding-round-at-3-billion-valuation/articleshow/71626418.cms.

Freeman, D., & Siegfried, R., Jr. (2015). Entrepreneurial leadership in the context of company start-up and growth. Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(4), 35–39.

Garg, A., & Shivam, A. K. (2017). Funding to growing startups. Research Journal of Social Sciences, 10(2), 22–31.

Global Entrepreneurship Index. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338547954_Global_Entrepreneurship_Index_2019.

Gooptu, B. (2019, October 23). SHL buys aspiring minds in all-cash deal. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/shl-buys-aspiring-minds-in-all-cash-deal/articleshow/71715717.cms?from=mdr.

Hamilton, R. H. (2001). E-commerce new venture performance: How funding impacts culture. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 11(4), 277–285.

Hayton, J. C., George, G., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). National culture and entrepreneurship: A review of behavioral research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 33–52.

Hechavarría, D. M. (2016). The impact of culture on national prevalence rates of social and commercial entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(4), 1025–1052.

Hmieleski, K. M., Cole, M. S., & Baron, R. A. (2012). Shared authentic leadership and new venture performance. Journal of Management, 38(5), 1476–1499.

Hmieleski, K. M., & Ensley, M. D. (2007). A contextual examination of new venture performance: Entrepreneur leadership behavior, top management team heterogeneity, and environmental dynamism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(7), 865–889.

Hofstede Insights. Retrieved from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/india/.

Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2), 75–89.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. London and New York: McGraw Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organisations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). USA: McGraw-Hill.

Jensen, S. M., & Luthans, F. (2006). Entrepreneurs as authentic leaders: Impact on employees’ attitudes. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(8), 646–666.

Joshi, D., & Achuthan, S. (2018). Leadership in Indian high-tech start-ups: Lessons for future. In B. S. Thakkar (Ed.), The future of leadership—addressing complex global issues (pp. 39–91). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jovanović, M., Miloš, J., & Petković, J. (2018). The role of culture in entrepreneurial ecosystem: What matters most? 16th International Symposium Symorg 2018—Doing Business in the Digital Age: Challenges, Approaches and Solutions, at Zlatibor, Serbia.

Kakar, S., Kakar, S., Kets de Vries, M. F. R., & Vrignaud, P. (2002). Leadership in Indian organizations from a comparative perspective. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 2(2), 239–250.

Kang, J., Solomon, G., & Choi, D. (2015). CEO’s leadership styles and managers’ innovative behaviour: Investigation of intervening effects in an entrepreneurial context. Journal of Management Studies, 52(4), 531–554.

Kanungo, R. N., & Misra, S. (2004). Motivation, leadership, and human performance. In J. Pandey (Ed.), Psychology in India revisited: Developments in the discipline (Vol. 3, pp. 309–341). New Delhi: Sage.

Lerner, C. (2017). Explosive growth: A few things I learned while growing my startup to 100 million users & losing $78 Million. Clifford Ventures Corporation, 1st Ed.

Luger, M. I., & Koo, J. (2005). Defining and tracking business start-ups. Small Business Economics, 24, 17–28.

Maclachlan, M. (2013). Indulgence v/s restraint: The sixth dimension. Retrieved from https://www.communicaid.com/cross-cultural-training/blog/indulgence-vs-restraint-6th-dimension/.

Malik, Y. (2019, April 16). Unacademy: Helping people turn educators to millions of students. Retrieved from https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/unacademy-helping-people-turn-educators-to-millions-of-students-119041600486_1.html.

Mansur, R. (2019, July 19). Here’s how talent evaluation company Aspiring Minds quantifies employability to bridge skill gaps. Retrieved from https://yourstory.com/smbstory/aspiring-minds-gurugram-employability-test-nsdc.

Modgil, S. (2017, October 9). The Wingify story: How Paras Chopra outgrew his humble ambition of earning $1,000 a month to build A $18 mn SaaS startup. Retrieved from https://inc42.com/startups/wingify-paras-chopra-saas-startup/.

Mukherjee, S. (2020, January 28). Ather energy to add 100,000 units in capacity to meet demand for electric two-wheelers. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/newsbuzz/ather-energy-to-add-100000-units-in-capacity-to-meet-demand-for-electric-two-wheelers/articleshow/73698815.cms.

Nair, S. (2015, December 31). Start-up India: Nine reasons for India’s exponential growth in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Retrieved from https://www.firstpost.com/business/start-up-india-nine-reasons-for-indias-exponential-growth-in-the-entrepreneurial-ecosystem-2558462.html.

Newbery, R., Lean, J., Moizer, J., & Haddoud, M. (2018). Entrepreneurial identity formation during the initial entrepreneurial experience: The influence of simulation feedback and existing identity. Journal of Business Research, 85, 51–59.

Rozani, A. (2019, February 25). Here’s why 2019 is going to be the year of digital entrepreneurs. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/328903.

Rusu, C. (2014). Culture—Moderator of the relationship between contextual factors and entrepreneurial outcomes. Managerial Challenges of the Contemporary Society, 7(1), 63–67.

Shenoy, S. (2019). How startups can effectively measure customer satisfaction through feedback. Retrieved from https://yourstory.com/2019/07/startups-measure-customer-satisfaction-feedback.

Sheth, A., Krishnan, S., & Samyukktha, T. (2020). India venture capital report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.bain.com/insights/india-venture-capital-report-2020/.

Singh, N., & Krishnan, V. R. (2007). Transformational leadership in India: Developing & validating a new scale using grounded theory approach. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 7(2), 219–236.

Sinha, J. B. P. (2000) Patterns of work culture: Cases and strategies for culture building. New Delhi: Sage.

Suneja, K. (2019, May 23). Government plans Rs. 1,000 crore fund for startups in priority areas. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/government-plans-rs-1000-crore-fund-for-startups-in-priority-areas/articleshow/69450803.cms?from=mdr.