Abstract

Political liberals and political conservatives endorse opposing views about how to reduce gun violence in the United States. Liberals support greater restrictions on who can purchase and carry firearms whereas conservatives oppose such restrictions. We tested eight explanations for the political divide in support for a specific policy: campus carry. Four explanations originate from researchers who argue—often with limited evidence—that liberals and conservatives differ in psychological tendencies, beliefs, and perceptions, and that these differences drive their opposing policy views (such as views on immigration). However, our analyses revealed little support for any of these explanations, with few or no differences between liberals and conservatives in intolerance of uncertainty, belief in a dangerous world, perceived relative power, or perceived government threat. Conservatives were more likely to endorse traditional views of masculinity, but views of masculinity did not explain greater opposition to gun restrictions among conservatives. Two explanations received some support: conservatives were more likely than liberals to perceive safety as a personal responsibility and to perceive gun ownership as part of their identity. These perceptions, in turn, corresponded with greater opposition to gun restrictions. The strongest explanation for the political divide on gun policy was that conservatives, compared with liberals, were more likely to view guns as a means to safety rather than a threat to safety. Viewing guns as a means to safety was strongly linked to opposing gun restrictions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Gun violence in the United States is a public health emergency . According to a recent report, almost 40,000 people died in firearm-related injuries in 2017 [1]. Legislative solutions to this emergency tend to fall into two camps—legislation that restricts gun access (e.g., increasing background checks and banning military-style rifles) and legislation that increases gun access (e.g., allowing concealed guns on school campuses or arming teachers). In the United States, legislators are largely divided along party lines in their support for the different solutions. For example, the Bipartisan Background Checks Act (2019) [2] received near unanimous support in the House of Representatives from Democrats, yet received only token support from Republicans. The political divide also appears in the general population. A recent poll showed that support for stricter gun laws was sharply divided among Democrats (85% supporting) and Republicans (24% supporting) [3].

In this chapter, we describe the results from a survey that we conducted to understand why political conservatives and political liberals differ in their attitudes toward gun rights and restrictions. The survey explored several potential explanations for liberal/conservative differences in gun attitudes. We describe each of the explanations then describe which explanations received support in our survey and which did not. We conclude by discussing possible approaches to bridging the gun divide.

Broad Explanations for the Political Divide on Gun Attitudes

In the United States, people who identify with the Republican Party are generally more conservative and tend to support policies that maintain or expand gun access. In contrast, people who identify with the Democrat Party are generally more liberal and tend to support policies that restrict gun access [4]. Recent evidence suggests that party identification is among the strongest predictors of gun policy attitudes [4] and gun ownership [5]. The differences in attitudes even extend to Republicans and Democrats who own guns; 82% of Republican gun owners favor expanding concealed carry laws compared with 41% of Democrat gun owners.

Why do political conservatives favor solutions to gun violence that entail expanding gun rights, whereas political liberals favor solutions to gun violence that entail expanding gun restrictions? Theorists in psychology and political science have proposed two broad categories of explanations for the relationship between political ideology and policy preferences. The first category represents a person approach (much like a “nature” approach [6]) to thought and behavior and rests on the observation that people are fundamentally different in a variety of ways. For example, people differ biochemically in the quantity of various hormones and neurotransmitters produced in their body. They also differ biologically in the activation of brain structures such as the amygdala and hippocampus in response to stimuli [7]. Finally, they differ in the genes they receive from their parents . Over the last several decades, researchers have documented how these person-variables can influence thinking and behavior. They shape various characteristics of people including their personality, intelligence, and how they interpret and respond to situations [6].

Some theorists have argued that these fundamental person-variables account for differences in the beliefs of political liberals and political conservatives. For example, researchers have proposed that liberals and conservatives differ fundamentally on characteristics such as threat sensitivity [8], morality [9], thinking styles [10], and the Big-Five personality traits of openness and conscientiousness [11]. According to the person approach these differences affect psychological responses such as attitudes, values, expectations, beliefs, and behavior. For example, some researchers argue that greater political conservativism corresponds with greater threat sensitivity, and that political conservatives may be more attuned to dangers in their environment and thus more inclined than are political liberals to view even ambiguous stimuli as threatening [8]. According to the person approach, individual differences between political liberals and political conservatives account for the opposing policy preferences of the two groups. For example, greater threat sensitivity among political conservatives corresponds with their placing greater value on issues such as national security [8].

The second category of explanations represents a situational approach to thought and behavior (much like a “nurture” approach [6]) and proposes that people differ in the culture, experiences, and situations they encounter. These “situations” shape people’s values, which are important determinants of expectations, attitudes, and behavior [12]. For example, differences in media exposure presumably can lead to different values, which can prompt differences in political ideology and positions on political issues. Of course, it also possible that political ideology can lead people to gravitate toward different media sources, a point we return to later.

Research in social psychology documents the powerful effects that situations exert on thinking and behavior. For example, national security threats (e.g., a terrorist attack) shift people’s attitudes toward more conservative values [13], whereas healthcare threats (e.g., learning a child with cancer was denied insurance coverage by the parent’s insurer) shift people’s attitudes toward more liberal values [14]. This latter finding suggests that both liberals and conservatives are sensitive to threat, which is contrary to the person-based argument that conservatives are particularly threat-sensitive [8]. According to the situation approach, the different experiences and culture of political liberals versus political conservatives result in different values that prompt them to be sensitive to different threats. For example, conservatives in the United States who have more pro-life values are more likely to see Planned Parenthood as a threat because they believe the organization threatens pro-life values. Liberals in the United States tend to be more concerned with the environment and thus are more likely to see climate skeptics as a threat because they the skeptics undermine pro-environmental efforts [15].

Although the person and situation approaches offer broad frameworks for explaining thinking and behavior generally, and political preferences more specifically, the two are not as distinct as they might appear. Instead, they influence both each other and political outcomes (e.g., policy positions) in complex ways. First, researchers have long noted that the two approaches represent complementary rather than competing explanations for thinking and behavior. Put simply, both the person and the situation can influence how people think and behave [16]. Second, the person and the situation can interact to influence thought and behavior, that is, whether a person variable influences thought or behavior depends on the situation . For example, belief in a dangerous world (a person variable) may correspond with a preference for fewer gun restrictions among people with experiences (a situational variable) that have led them adopt more conservative values, but correspond with a preference for more gun restrictions among people with experiences that have led them to adopt more liberal values. Such a finding would demonstrate that the same experience could have opposite effects on people. Alternatively, political conservatives may oppose most gun restrictions regardless of their experiences, whereas political liberals may oppose most gun restrictions only when they personally have experienced violent crime. Such a finding would demonstrate that experience influences some people but not others.

Third, the person and situation factors can have a bidirectional influence: personal factors can influence situational factors and situational factors can influence personal factors [17]. Consider first how personal factors can influence situational factors. Personal factors can influence the situations that people select for themselves. For example, a predisposition to be fearful and/or anxious can lead people to seek environments and media sources that align with their personality (e.g., opting to live in a gated community, preferring news sources that confirm personal views) and to affiliate with other like-minded people (e.g., others who share one’s beliefs or outlook on the world). Now consider how situational factors can influence the person. For example, culture, media exposure, and environment can shape personality (e.g., produce chronic anxiety or fearfulness) and prompt affiliations with others who reinforce some aspects of a person’s personality but not others (e.g., friending like-minded acquaintances on Facebook).

This third complexity—the fact that the broad categories of person and situation can influence each other—can make it difficult to determine which is responsible (and to what extent) for how people think and behave when it comes gun rights and restrictions. Thus, although the person and situation explanations have received considerable attention among political psychologists attempting to explain the divergent attitudes of political conservatives and political liberals, their utility in predicting specific policy positions such as positions on gun rights and restrictions, seems limited.

Specific Explanations for the Political Divide in Gun Attitudes

An alternative to the broad explanations for the political divide in gun attitudes are specific explanations that offer single causal mechanisms by which political ideology links to policy positions. We know of at least eight specific explanations for why political liberals and political conservatives differ in their gun attitudes (see Fig. 9.1). Our interest was in examining which of the explanations have merit and which do not. The eight explanations undoubtedly overlap. Importantly, we organize our discussion around the beliefs of political conservatives (i.e., this is what political conservatives believe or may believe, whereas political liberals believe or may believe otherwise). In no way do we wish to imply that the views of conservatives need explaining, whereas the views of liberals do not. We could have just as easily focused on the views of liberals. Our interest is in understanding why the two groups differ and we merely picked one group as the reference throughout to make the arguments easier for readers to follow.

Uncertainty Avoidance

Life is filled with uncertainty. People face uncertainties about issues such as whether they will remain healthy, whether their children will turn out okay, who will buy the house next door, and whether they will have enough money saved for retirement. Not all people are comfortable with uncertainty; some people find uncertainty more distressing than do others [18]. One explanation for the observed differences between liberals and conservatives asserts that the two groups differ in their tolerance for uncertainty and thus their desire to avoid uncertainty. Theory and research suggest that political conservatives are less tolerant of uncertainty than are political liberals [19,20,21]. Uncertainty is distressing because it often means change and some people find change unpleasant.

Although the link between political identification and intolerance for uncertainty appears well established, the explanation for why intolerance for uncertainty leads to support for gun rights is tenuous. One possibility is that guns provide a feeling of comfort or security that diminishes the distress associated with uncertainty . However, people can feel uncertain about many things and it is unclear how guns could provide comfort and reduce the distress that many people associate with uncertainty. For example, owning a gun seems unlikely to reduce many types of uncertainty (e.g., climate change, changes in the job market, or changes in legislation regarding same-sex marriage and marijuana). Moreover, reducing gun restrictions may actually increase uncertainty for people who find guns threatening and view their safety as threatened when guns are more readily available in a community.

Perceived Relative Power

Having personal power influences control over events in one’s life and allows people to acquire the things they want, including good jobs, nice homes, and desirable mates. A lack of power undermines one’s capacity to achieve these outcomes. People vary in their perceived relative power: how much power and control they perceive they have relative to others, relative to the past, and relative to what they believe they deserve. Research links perceptions of low personal power to greater gun ownership [22], and perhaps for good reason. Guns are empowering in many ways, including their utility for self-defense and intimidating others. As such, guns may provide users with a sense of power and control they may feel they otherwise lack [18, 23]. Although the empowering function of guns is largely untested, one study provided hints that guns can influence personal perceptions of control. Specifically, research participants who imagined holding a gun reported greater perceptions of personal control in their lives (i.e., the perception that one’s actions are responsible for personal life outcomes). It is noteworthy that this effect emerged for political conservatives but not for political liberals [24], which suggests that conservatives may be more likely than liberals to experience a power or control boost from having a gun.

Traditionally, political, social, and economic power in the United States has been concentrated among one demographic group: White men [25]. Laws that discriminated against women and minorities in the right to vote and hold certain jobs illustrates this power differential. Although White men today still hold power disproportionate to their numbers in the population, they may very well perceive that their relative power is declining. To take one example, the US Senate was comprised entirely of White men 100 years ago in 1920, and 95% White men 50 years later in 1970. In 2020, that number has fallen to 70% [26, 27]. Further, political conservatives are more likely than are political liberals to be White males [28]. According to the perceived relative power explanation, political conservatives are more likely than are political liberals to favor policies that sustain or expand gun rights because they are more likely to perceive a decline in personal or relative power and view guns as a means of augmenting their declining power.

The perceived power explanation is limited in much the same way that the uncertainty avoidance explanation is limited. Although White men, who make up a large percentage of US conservatives, may be losing actual power or perceive they are losing personal or relative power, they are unlikely to be the only group that feels disempowered. The African American community and the LGBTQ community—all groups that tend to receive unfavorable treatment [29, 30] and tend to vote liberal [31, 32]—while not losing power, likely believe they have little power or less power than they should. Yet contrary to the perceived power explanation, these communities are more likely to support gun restrictions [33, 34]. Finally, this explanation neglects the possibility that liberals, especially when conservatives control the executive or legislative branches of government, also feel a loss of power or lack of control.

Government Threat

A common argument among proponents of gun rights is that gun restrictions infringe on their ability to protect themselves and their country from a tyrannical federal government [35, 36]. Implicit in this argument is a distrust of the government. Consistent with this explanation is the finding that distrust of the federal government predicts owning a gun [37]. However, the evidence is mixed on whether political conservatives, compared with political liberals, are more distrustful of the government, or are more likely to perceive the US government as inclined to become tyrannical. Some research shows that greater political conservatism corresponds with greater system justification—a tendency to justify, defend, and bolster the existing power structure, which would imply that conservatives are generally more trustful of the government than are liberals [19, 38]. Other studies show that people trust the government more when their political party is in power. Thus, Republicans tend to trust the government more during a Republican presidency, and Democrats trust the government more during a Democratic presidency [39, 40]. However, the effect appears stronger for conservatives: a recent review paper concluded that political conservatives are more distrustful of the government than are liberals when the government is controlled by the opposing party [41]. In sum, it remains unclear whether distrust of the government explains the greater support for gun rights policies among political conservatives than political liberals.

Belief in a Dangerous World

People differ in the extent to which they perceive the world as dangerous [42]. People who believe in a dangerous word are inclined to view the world as competitive and violent [43]. Some research has linked belief in a dangerous world to greater political conservatism [44, 45]. In addition, research finds that the more people believe that the world is dangerous, the more likely they are to own a gun for protection reasons, to perceive guns as effective in protecting themselves from harm, and to favor fewer gun restrictions [44]. When viewed together, this research suggests that political conservatives support fewer gun restrictions because they believe the world is dangerous.

Traditional Views of Masculinity

Masculinity refers to behavior, traits, and people commonly associated with males [46]. The link between having guns and being male has a long history in the United States. Men are more likely than women to serve in the armed forces [47], to be in professions that require having a gun [48], and to own guns [49]. The dolls/action figures that boys play with often involve weapons such as guns, whereas the dolls/action figures that girls play with do not [50]. In short, guns are likely far more central to the identity of boys and men than to the identity of girls and women.

Some theorists have argued masculinity is precarious—it is not innate but rather achieved through stereotypical masculine behavior [51, 52]. Men can also achieve or establish their masculinity by publicly displaying the trappings of masculinity, or expressing attitudes and beliefs that are consistent with masculinity. Consistent with this theorizing is the argument that one appeal among men for carrying a firearm is that carrying a firearm bolsters the masculine self-image of a powerful protector who can inflict violence if necessary [53, 54]. Moreover, gang members acknowledge that guns are a tool for projecting an image of being tough [55]. Given that owning and using a gun are linked to masculinity, holding attitudes in favor of gun rights should also correspond with greater endorsement of traditional masculinity.

In a nutshell, it is possible that the more a person is comfortable with or supports traditional masculinity and traditional sex roles, the more the person will support gun rights over gun restrictions. Political conservatives are more likely than are political liberals to endorse traditional masculinity [56] and it may be the case that their support for gun rights stems from their endorsement of traditional masculinity.

Personal Responsibility for Safety

An underlying theme of many gun rights messages is that safety is one’s personal responsibility [57]. Part of the message is that law enforcement can do little to stop or prevent violent crime and, according to a US Supreme Court ruling, is not legally required to protect people from violent crime [58]. To the extent that people believe that their safety and protection is their personal responsibility, they should favor policies that allow them unfettered access to the means for self-protection. Thus, people who endorse this belief presumably support legislation that protects or expands gun rights. Although we know of no evidence that political conservatives are more likely than political liberals to regard safety and protection as their personal responsibility, a few studies have suggested that political conservatives are more likely to believe that they, rather than outside forces, are responsible for their personal outcomes . For example, political conservatives are more likely than political liberals to attribute internal responsibility for personal outcomes such as poverty [59] and health [60]. Accordingly, political conservatives may be more likely than political liberals to oppose gun restrictions because they believe that their personal protection is their responsibility and that gun restrictions threaten their ability to protect themselves.

Gun Ownership Identity

A large part of how people think about themselves—their identity—comes from the groups to which they belong [61]. People, of course, opt to join groups whose members share their attitudes and beliefs. However, it is also true that once they become part of a group, people tend to adopt the beliefs and attitudes of the group. Part of the adoption process can be explained by consistency theory. People seek consistency between their attitudes, beliefs, and behavior; inconsistency creates discomfort [62]. Thus, people conform to the attitudes and beliefs of the members of the groups to which they belong because to do otherwise feels uncomfortable. On the flipside, people seek to differentiate themselves from the groups to which they do not belong, particularly groups they view as standing in opposition to their own group. Thus, they often develop attitudes and beliefs that set them apart from or contrast with members of opposing groups.

For a variety of reasons, the politically conservative Republican Party has come to associate itself with the gun culture, that is, owing gun, using guns for recreation, and affiliating with national gun groups such as the National Rifle Association. In contrast, the politically liberal Democratic Party has not. If anything, over the last two decades people have come to view the Democratic Party as opposing the gun culture. One reason likely reflects the narrow passage of the assault weapons ban by a Democratic-controlled Congress in 1994 [63]. A consequence of this passage was that the NRA dramatically increased its financial contributions to Republican candidates for office and dramatically reduced its financial contributions Democratic candidates for office [64].

The shift to a sharp imbalance in political contributions appears to have set in motion a growing polarization in the attitudes of members of the two parties, one that feeds on itself. Republicans may increasingly identify with gun owners and see gun owners as part of their ingroup and see non-owners as part of the outgroup. Not surprising, 77% of NRA members identify as Republicans (compared to 58% of non-NRA gun owners) [5]. By comparison, Democrats may increasingly identify with non-owners and see gun non-owners as part of their ingroup, and see gun owners as part of the outgroup. And, once people come to view gun owners (or non-owners) as part of their ingroup, they process information about guns in ways that are biased toward protecting and justifying that identity [61]. They also gravitate toward stances that are consistent with their political party and distinguish them from the opposing political party. Thus, according to the identity explanation, political conservatives may oppose gun restrictions because they identify more with gun owners and the gun culture. Political liberals, by contrast, may support gun restrictions because they identify more with non-owners.

Gun as a Source of Safety

All people have basic needs they must satisfy to survive and thrive [65]. Among the most basic needs is the need for safety. Some researchers have argued that this need for safety has an evolutionary basis [66], affects how people think, feel, and behave [67], and is important to psychological well-being [68]. Yet people differ in their views of the role that guns play in achieving safety. Whereas some people perceive guns as a means to safety, others view guns as a threat to safety. Moreover, people who own guns for protection reasons are more likely than people who own guns for other reasons (e.g., for sport or collecting) to favor policies that broaden gun rights [69].

The difference between political conservatives and political liberals in their support for gun rights may arise from group differences in gun safety perceptions. Specifically, political conservatives may be more likely than are political liberals to own guns for protection reasons and to perceive guns as a source of safety rather than a threat to safety. Although we know of no evidence bearing on the issue, the difference in gun perceptions may stem from the two groups relying on different media sources for news and information. Conservative media sources may be more inclined than liberal media sources to emphasize the safety benefits of guns and gun ownership, such as presenting statistics on how guns save lives, or stories of how people protected themselves from perpetrators with guns. Conversely, liberal media sources may be more inclined to emphasize the safety costs of guns, such as presenting statistics on the number of gun deaths in the country, particularly compared with countries with stricter gun laws, or stories about perpetrators who used guns to harm victims. A quick internet search reveals numerous news editorials and opinion pieces reporting that news outlets are biased toward portraying guns and gun owners unfavorably (i.e., as dangerous). But these editorials and opinion pieces are themselves published in news outlets, many of which are likely biased toward portraying guns and gun owners favorably (i.e., as not dangerous). In short, it seems quite likely that different news outlets are biased toward portraying guns differently—as a means to safety versus a threat to safety—depending on their political tilt.

Testing the Explanations for Political Differences in Gun Policy Positions

We carefully constructed a survey that included items measuring the eight explanations for why political liberals and political conservatives differ in their support for gun policy. We assessed belief in a dangerous world, with items such as, “The world is a dangerous place.” We assessed uncertainty avoidance using items such as, “Uncertainty makes me feel anxious.” We assessed perceived relative power with items such as, “I have less control over what happens in my life than I used to.” We assessed government distrust with items such as, “I need to protect myself against a potentially oppressive government.” We assessed identity as a gun owner with items such as, “Owning a gun is part of who I am.” We assessed traditional views of masculinity with items other researchers have used such as, “Men who don’t like masculine things are not real men” [52, 70]. We assessed the belief that people are personally responsible for their safety with items such as, “It is my responsibility to protect myself.” Finally, we assessed perceptions of guns as a source of safety with items such as, “Carrying a gun makes me feel safe.” For all items, participants indicated how true the statement was for them personally.

Finally, we measured political ideology with a single item that ranged from 1 = extremely liberal to 7 = extremely conservative, and measured support for a single gun policy that was highly relevant to our sample: allowing people with a concealed carry license to carry a concealed gun on college campuses (i.e., “Campus Carry”).

We sent our survey via email to faculty , students, and staff at the University of Florida, a large land-grant university in the southeast United States. Compared with the US population, our sample was younger (our sample mean age = 25.00 years; US median age = 38.2 years in 2018; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019), more educated (percentage earning a graduate degree in our sample = 26.9%; percentage in the United States as of 2015 = 12% [71]), and more liberal (40.6% liberal compared to 25% liberal in the United States [72].).

We conducted our survey over a 2-week period between October and November 2018 and received responses from almost 17,000 people. Although no major incident of gun violence occurred during our survey, it is noteworthy that our survey occurred 8 months after the February 18, 2018, shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in South Florida that left 17 people dead. Major gun violence events tend to deepen, at least temporarily, the divide in gun attitudes, but the effect is small and presumably would strengthen our ability to identify the reasons that political conservatives and political liberals differ in the beliefs about guns [73].

Figure 9.2 presents a scatterplot that crosses political ideology with support for campus carry. The dots represent the number of people falling into each quintile of our measure of support for concealed carry (higher numbers = greater support) at each level of our 7-step measure of political ideology. As is clear from the figure, respondents who were politically conservative reported stronger support for legislation legalizing concealed carry than did respondents who were politically liberal. As evident by the preponderance of dots in the lower left corner of the figure, political liberals strongly opposed legalizing concealed carry.

Next, we examined the eight explanations we offered for why political conservatives and political liberals differ in their support for campus carry legislation. Table 9.1 presents the correlations. Correlations are a measure of the strength and direction of a relationship, and range from −1.00 to +1.00. Irrespective of the valence of the correlation (i.e., whether it is negative or positive), the larger the number, the stronger the relationship. Thus, a correlation of 0.50 (or − 0.50) indicates a stronger relationship than a correlation of 0.10 (or − 0.10). A correlation of 0.50 and − 0.50 are equal in strength. The valence of a correlation indicates the direction of the relationship. Thus, positive correlations indicate that people who score higher on one measure in the relationship also score higher on the other measure in the relationship. We worded our measure of political ideology so that higher numbers indicate being more politically conservative. Thus, a positive relationship between an explanation and political ideology indicates that political conservatives were more likely than were political liberals to say the explanation was true of them. A negative relationship indicates that political conservatives were less likely than were political liberals to say the explanation was true of them.

The first column of correlations in Table 9.1 indicates the relationship between political ideology and the extent to which survey participants reported each explanation was true of them. The asterisks indicate the statistical probability that the two variables are related by chance. Traditionally, if that probability is low (in our case, we set the probability at 1 in 1000), then the result is considered statistically significant . However, more important than whether the correlation is significant is the size of the correlation (how far it differs from zero). The first four correlations in the column are quite small (0.14 or less), indicating that political conservatives differed little from political liberals in how much they said that the statements representing the explanations (uncertainty avoidance, perceived relative power, government threat, belief in a dangerous world) were true of them. These correlations indicate that the first four explanations explain little of the difference between political conservatives and political liberals in their support for legalizing campus carry.

The next three correlations in the first column ranged from small to medium. Political conservatives were more likely than were political liberals to hold traditional views of masculinity, to believe that their personal safety is their responsibility, and to view guns as part of their identity. The final correlation in the first column, however, was by far the largest, indicating that political conservatives were far more likely than were political liberals to perceive guns as a source of safety rather than a threat to safety.

The second column of correlations in Table 9.1 indicates the relationship between how much people reported the explanation as true of them and their support for legalizing campus carry. Once again, the first four correlations in the column were quite small (0.18 or less), indicating that people who did and did not support campus carry differed little in the extent to which they said the statements representing the explanations were true of them. The fact that these correlations were so small indicates that uncertainty avoidance, perceived relative power, government threat, and belief in a dangerous world tell us little about why some people favor fewer gun restrictions and other people favor more gun restrictions.

Once again, the next three correlations in the column range from small to moderate. People were more likely to support campus carry legislation if they held traditional views of masculinity, saw their personal safety as their responsibility, and viewed guns as part of their identity. Finally, the last correlation was the largest (huge in fact), indicating that the more our survey respondents supported campus carry, the more likely they were to view guns as a means (rather than threat) to safety.

The correlations reveal how political ideology, support for campus carry, and the eight explanations are interrelated. The correlations can also tell us if some explanations are not viable. In our case, the correlations lead us to dismiss the first four explanations for political differences in support for campus carry. Importantly, although the correlations can provide hints, they do not reveal which explanation or explanations best explain the relationship between political ideology and policy support. To address this question, we need to examine statistically how much of the relationship between political ideology and policy support we can attribute to each of the explanations. Statisticians use the term indirect effect to describe the path from the predictor (i.e., political ideology) to the outcome (i.e., policy position) through each explanation. Statisticians use the term direct effect to describe the relationship between the predictor (i.e., political ideology) and the outcome (i.e., policy position) after removing the indirect effects. Our interest is in the indirect effects. The larger the indirect effect, the more the explanation accounts for the relationship between political ideology and support for campus carry.

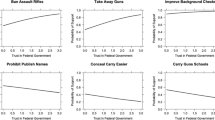

Figure 9.3 shows the magnitude of the indirect effect associated with each of our explanations. Unsurprisingly, given the correlations we observed in Table 9.1, the first four explanations (uncertainty avoidance, perceived relative power, government threat, and belief in a dangerous world) had zero to small indirect effects. The same was true for having a traditional view of masculinity. In short, none of these explanations help much in understanding why political conservatives are more likely to support campus carry. Of the remaining three predictors, viewing gun ownership as part of one’s identity and viewing personal safety as one’s responsibility explain a respectable proportion of the relationship between political ideology and support for campus carry. By far the strongest explanation of the relationship is perceiving guns as a means (rather than a threat) to safety. That is, our findings suggest that political conservatives are more likely than political liberals to support campus carry because they are more inclined to view guns as a means to safety.

Summary

We began with a simple question: why do political conservatives and political liberals differ so markedly in their thinking about how to reduce gun violence in the United States? We discussed eight explanations for the political divide in support for gun policies. Researchers have evoked some of these explanations to explain differences between political conservatives and political liberals in other areas. Our research failed to support some of these explanations with respect to support for campus carry for two reasons: (1) conservatives and liberals did not differ in their responses to our measures of the explanations, and (2) the explanations were unrelated to support for campus carry. We found evidence that viewing personal safety as one’s own responsibility and identifying with gun owners explained a respectable portion of the relationship between political ideology and support for campus carry. The strongest explanation, however, was viewing guns as a means (as opposed to a threat) to safety. Our findings suggest that political conservatives were more likely than were political liberals to a support policy (e.g., campus carry) that expanded gun rights because they viewed guns as a source of safety rather than a threat to safety.

In the United States, the sharp political divide between liberals and conservatives has pushed the country to the point of gridlock, undermining the government’s ability to address the crisis of gun violence. Our findings indicate that political liberals and conservatives differ in the solutions they support to reduce gun violence because they differ in their perceptions of the role that guns play in safety. Feeling safe is important to everyone. If we are going to reduce gun violence in a politically divided country, legislators need to craft policies that are sensitive to everyone’s safety needs and recognize that views on achieving safety differ from person to person. Specifically, policies should be sensitive to differences in the extent to which people believe they are personally responsible for their safety and differences in the extent to which people perceive gun ownership as part of their identity. But perhaps most importantly, lawmakers need to craft policies that do not place one group’s needs over the other’s, but rather satisfy the safety needs of both groups. Such policy is challenging, but is essential if we are to reduce gun violence in America.

References

Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian B, Arias E. Deaths: Final data for 2013 National vital statistics reports; vol 64 no 2. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016.

Bipartisan Background Checks Act. 2019. HR 8, 116th Congress.

Malloy T. Quinnipiac university poll. 2019. From https://poll.qu.edu/national/release-detail?ReleaseID=2592. Accessed March 2019.

Pearson-Merkowitz S, Dyck JJ. Crime and partisanship: how party ID muddles reality, perception, and policy attitudes on crime and guns. Soc Sci Q. 2017;98(2):443–54.

Parker K, Horowitz J, Igielnik R, Oliphant B, Brown A. America’s complex relationship with guns: an in-depth look at the attitudes and experiences of US adults. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2017.

Owen MJ. Genes and behavior: nature–nurture interplay explained by Michael Rutter. Oxford: Blackwell. 2006. 272pp.£ 14.99 (pb). ISBN 1405110619. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189(2):192–3.

Schreiber D, Fonzo G, Simmons AN, Dawes CT, Flagan T, Fowler JH, Paulus MP. Red brain, blue brain: evaluative processes differ in Democrats and Republicans. PLoS one. 2013;8(2):e52970.

Hibbing JR, Smith KB, Alford JR. Differences in negativity bias underlie variations in political ideology. Behav Brain Sci. 2014;37:297–350.

Graham J, Haidt J, Koleva S, Motyl M, Iyer R, Wojcik SP, Ditto PH. Moral foundations theory: the pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In: Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 47. New York: Academic Press; 2013. p. 55–130.

Kossowska M, Hiel AV. The relationship between need for closure and conservative beliefs in Western and Eastern Europe. Polit Psychol. 2003;24(3):501–18.

Carney DR, Jost JT, Gosling SD, Potter J. The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Polit Psychol. 2008;29(6):807–40.

Schwartz SH. Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1992;25(1):1–65.

Jost JT, Stern C, Rule NO, Sterling J. The politics of fear: is there an ideological asymmetry in existential motivation? Soc Cogn. 2017;35(4):324–53.

Eadeh FR, Chang KK. Can threat increase support for liberalism? New insights into the relationship between threat and political attitudes. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2020;11(1):88–96.

Losee JE, Smith C, Webster GD. Beyond severity: examining the relationship between individual differences and threat-related intentions. 2019; https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/btwsx.

Ross L, Nisbett RE. The person and the situation: perspectives of social psychology. London: Pinter & Martin Publishers; 2011.

Buss DM. Selection, evocation, and manipulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53(6):1214.

Kruglanski AW. The psychology of closed mindedness: New York: Psychology Press; 2013.

Jost JT, Glaser J, Kruglanski AW, Sulloway FJ. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(3):339.

Jost JT, Napier JL, Thorisdottir H, Gosling SD, Palfai TP, Ostafin B. Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33(7):989–1007.

Jost JT, Federico CM, Napier JL. Political ideology: its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:307–37.

Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355.

Leander NP, Stroebe W, Kreienkamp J, Agostini M, Gordijn E, Kruglanski AW. Mass shootings and the salience of guns as means of compensation for thwarted goals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2019;116(5):704.

Shepherd S, Kay AC. Guns as a source of order and chaos: compensatory control and the psychological (dis) utility of guns for liberals and conservatives. J Assoc Consum Res. 2018;3(1):16–26.

Liu WM. White male power and privilege: the relationship between white supremacy and social class. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(4):349.

United States Senate. Ethnic diversity in the senate. United States senate. 2019a. Retrieved August 8, 2019, from https://www.senate.gov/senators/EthnicDiversityintheSenate.htm

United States Senate. Women in the United States Senate. 2019b. Retrieved August 8, 2019, from https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/women_senators.htm

Taylor P. The next America: boomers, millennials, and the looming generational showdown: Hachette UK. New York; 2016.

Kattari SK, Whitfield DL, Walls NE, Langenderfer-Magruder L, Ramos D. Policing gender through housing and employment discrimination: comparison of discrimination experiences of transgender and cisgender LGBQ individuals. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2016;7(3):427–47.

Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Koenen K. Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1704–13.

Sides J, Tesler M, Vavreck L. The 2016 US election: how trump lost and won. J Democr. 2017;28(2):34–44.

Worthen MG. A rainbow wave? LGBTQ liberal political perspectives during Trump’s presidency: an exploration of sexual, gender, and queer identity gaps. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2020;17(2):263–84.

Conron KJ, Goldberg SK, Flores AR, Luhur W, Tashman W, Romero AP. Gun violence and LGBT adults: findings from the general social survey and the cooperative congressional election survey. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute, UCLA; 2018. Retrieved August 2019, from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Gun-Violence-Nov-2018.pdf

Rosentiel T. Views of gun control—a detailed demographic breakdown. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. Retrieved August 2019, from https://www.pewresearch.org/2011/01/13/views-of-gun-control-a-detailed-demographic-breakdown/

Celinska K. Individualism and collectivism in America: the case of gun ownership and attitudes toward gun control. Sociol Perspect. 2007;50(2):229–47.

Waugaman E. Understanding America’s obsession with guns: how did we get where we are? Psychoanal Inq. 2016;36(6):440–53.

Jiobu RM, Curry TJ. Lack of confidence in the federal government and the ownership of firearms. Soc Sci Q. 2001;82(1):77–88.

Jost JT, Banaji MR, Nosek BA. A decade of system justification theory: accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Polit Psychol. 2004;25(6):881–919.

Gershtenson J, Ladewig J, Plane DL. Parties, institutional control, and trust in government. Soc Sci Q. 2006;87(4):882–902.

Pew. Public trust in government: 1958–2019. 2017. Retrieved August 2019, from https://www.people-press.org/2017/12/14/public-trust-in-government-1958-2017/

Morisi D, Jost JT, Singh V. An asymmetrical “president-in-power” effect. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2019;113(2):614–20.

Altemeyer B. Enemies of freedom: understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1988.

Duckitt J, Wagner C, Du Plessis I, Birum I. The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: testing a dual process model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(1):75.

Stroebe W, Leander NP, Kruglanski AW. Is it a dangerous world out there? The motivational bases of American gun ownership. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2017;43(8):1071–85.

Van Leeuwen F, Park JH. Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personal Individ Differ. 2009;47(3):169–73.

Kimmel A, Aronson A. Men and masculinities. A social, cultural, and historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO; 2004.

Reynolds GM, Shendruk A. Demographics of the U.S. military. Council on Foreign Relations. 2018. Retrieved August 2019, from https://www.cfr.org/article/demographics-us-military

Duffin E. Gender distribution of full-time law enforcement employees in the United States in 2017 [graph]. Statista. 2018. Retrieved August 2019, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/195324/gender-distribution-of-full-time-law-enforcement-employees-in-the-us/

Parker K. Among gun owners, NRA members have a unique set of views and experiences. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2017. Retrieved August 2019, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/07/05/among-gun-owners-nra-members-have-a-unique-set-of-views-and-experiences/

Blakemore JE, Centers RE. Characteristics of boys’ and girls’ toys. Sex Roles. 2005;53(9–10):619–33.

Bosson JK, Vandello JA. Precarious manhood and its links to action and aggression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2011;20(2):82–6.

Vandello JA, Bosson JK, Cohen D, Burnaford RM, Weaver JR. Precarious manhood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(6):1325.

Connell RW. Masculinities. New York: Polity; 2005.

Stroud A. Good guys with guns: hegemonic masculinity and concealed handguns. Gend Soc. 2012;26(2):216–38.

Stretesky PB, Pogrebin MR. Gang-related gun violence: socialization, identity, and self. J Contemp Ethnogr. 2007;36(1):85–114.

Lottes IL, Kuriloff PJ. The effects of gender, race, religion, and political orientation on the sex role attitudes of college freshmen. Adolescence. 1992;27(107):675.

ProsCon.Org. Gun control – pros & cons. 2019. Retrieved August 2019, from https://gun-control.procon.org/

Castle Rock, Colorado v. Gonzales. 2005. No. 04–278. Retrieved August 2019, from https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/545/748.html

Weiner B. On sin versus sickness: a theory of perceived responsibility and social motivation. Am Psychol. 1993;48(9):957.

Chan EY. Political orientation and physical health: the role of personal responsibility. Personal Individ Differ. 2019;141:117–22.

Tajfel H, Turner JC, Austin WG, Worchel S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ Identity. 1979;56:65.

Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. New York: Stanford University Press; 1962.

Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. 1994. HR 335, 103rd Congress.

Lee K, Moore M. The NRA used to be a bipartisan campaign contributor, but that changed in 1994. Here’s why. Los Angeles Times. 2018. Retrieved August 2019 from https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-pol-nra-spending-20180303-story.html

Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50(4):370.

Sagarin RD, Sagarin R, Taylor T, editors. Natural security: A Darwinian approach to a dangerous world. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008.

Kenrick DT, Neuberg SL, Griskevicius V, Becker DV, Schaller M. Goal-driven cognition and functional behavior: the fundamental-motives framework. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(1):63–7.

Carroll PJ, Arkin RM, Wichman AL, editors. Handbook of personal security. New York: Psychology Press; 2015.

Shepperd JA, Pogge G, Losee JE, Lipsey NP, Redford L. Gun attitudes on campus: united and divided by safety needs. J Soc Psychol. 2018;158(5):616–25.

Kroeper KM, Sanchez DT, Himmelstein MS. Heterosexual men’s confrontation of sexual prejudice: the role of precarious manhood. Sex Roles. 2014;70(1–2):1–3.

Ryan CL, Bauman K. Educational attainment in the United States: 2015. Population characteristics. Current population reports. P20–578. US Census Bureau. 2016.

Saad L. U.S. conservatives outnumber liberals by a narrow margin. Gallup. 2017. Retrieved August 2019, from https://news.gallup.com/poll/201152/conservative-liberal-gap-continues-narrow-tuesday.aspx

Stroebe W, Leander NP, Kruglanski AW. The impact of the Orlando mass shooting on fear of victimization and gun-purchasing intentions: not what one might expect. PloS one. 2017;12(8):e0182408.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Losee, J.E., Pogge, G., Lipsey, N.P., Shepperd, J.A. (2021). Understanding the Political Divide in Gun Policy Support. In: Crandall, M., Bonne, S., Bronson, J., Kessel, W. (eds) Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55513-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55513-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-55512-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-55513-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)