Abstract

Palliative care has many action scenarios, as well as a diversity of care models, that can be adapted depending on the needs, resources, and socio-cultural context in which care is being provided. In-hospital care often represents a challenge for palliative care teams. A hospice care setting may provide a better model for support of families and attention to the special needs of children with life-limiting illness. In 2011, Guatemala opened its first pediatric hospice, directly linked to the National Pediatric Oncology Unit of Guatemala (UNOP), creating an interesting model in which the hospital palliative care team continues with the care of patients admitted to the hospice. This unique operation maintains optimal continuity of care. This model of hospice care in a low-income country has garnered attention from other low- and middle-income countries and may represent a model for improving the provision of palliative care for patients in countries with similar conditions for medical care.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Our Location

Guatemala is a country located in Central America, which has approximately 15 million inhabitants [1] in an area of 108,800 square kilometers, with coasts to the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean, as well as borders with the countries of Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and Belize. In addition, we have 59.3% of the population in poverty and 23% in extreme poverty in the last census [2]. We still have high levels of illiteracy and malnutrition and high rates of maternal mortality.

It is also good to mention that we have 22 indigenous groups, each with different characteristics such as languages, worldviews, and manifestations of spirituality. Having so much diversity in the same geographic area represents a challenge for the health system that struggles to interact with different beliefs, values, and points of view that influence the health-disease process.

Under these circumstances, a group of private companies decide to undertake an ambitious project by opening the first pediatric cancer hospital, the National Pediatric Oncology Unit of Guatemala, (in Spanish Unidad Nacional de Oncología Pediatrica (UNOP)), which opened in 2000. UNOP has unique infrastructure and philosophies of care that have been sustained since the hospital opened. These include a strong supportive relationship with the foundation AYUVI, who have helped to obtain financial resources for patient care. These resources come, in different proportions, from the Ministry of Health, contributions from civil society, and various alliances in both the public and private sectors. This collaborative and enduring relationship with AYUVI has been central to UNOP’s ability to remain sustainable and grow.

One of the most important premises of the work at UNOP is to provide free access to quality pediatric cancer care for any child in Guatemala; this has created the opportunity to achieve cure rates similar to those of high-income countries. The number of new patients diagnosed with cancer each year has grown to a high of 560 patients in 2019. This represents a positive impact because year after year we see patients who can resume their lives after facing the process of diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from cancer.

Another value present in the work of UNOP since its inception is the importance of interdisciplinary team care. Oncologists, nutritionists, pharmacologists, nurses, intensivists specialists, surgeons, orthopedists, psychologists, social workers, child life specialists, and volunteers all work shoulder to shoulder in coordination throughout the course of care for children with cancer.

Important Changes in Care

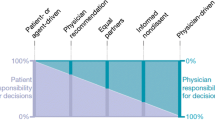

Five years after the opening of UNOP, under the direction of Dr. Federico Antillón and Dr. Patricia Valverde, Dr. Silvia Rivas (a pediatric intensivist) was invited to develop a clear plan of care for patients with high-risk, low-prognosis disease. The overarching goals were to create improved attention to symptom management and reduction of suffering, programs to decrease abandonment, and education of medical personnel in communication, decision-making, and coordination of other projects that impact the treatment of patients and the support of their families. A decision was made to change the name of the team (that would be charged with instituting this new plan of care) from the palliative care team to the integral medicine team. The intention was to more clearly convey the transdisciplinary nature of the care provided by the team and to make it part of care for patients from the time of diagnosis throughout the disease and treatment process. Since then, more people have been added to the team, improving attention and creating a model that includes not only the integral medicine team but also an algorithm for initiating care which was developed to ensure those patients who are most in need of intervention receive it immediately and help guide the future interventions of each team member strategically.

Below is a table illustrating both the growth in new diagnoses and the number of patients receiving care from the integral medicine team (Table 1).

Patients to whom we can only offer palliative care could be treated at the hospital or at home, although, due to geographical difficulties and safety/security, it was not possible to make home visits to all patients. It should be mentioned that some patients must travel 8–10 hours on the way to attend their appointments, while others travel 2 days, because transportation to leave from their villages is not available on a daily basis. Although some patients live closer to UNOP, it is not possible to make home visits because the areas in which they live are considered too dangerous. For these families, patients are monitored as closely as possible by phone, but sometimes they must return to the hospital for admission. This has created a problem with bedspace, creating daily census at the 90–100% levels. This created an especially urgent need for a designated space for palliative patients.

Dreaming of a Hospice

In 2011, a volunteer approached the integral medicine team, Ms. Myriam Aceituno, who had been very active in providing financial and logistical resources for the transfer of patients to their homes and provision of critical support for families. An architect by profession, her role had been to assist with charitable financial and personal support resources. However, her dream was to find a physical space that could address the important needs of patients at end of life. She wanted to find a place near a lake, using a space donated by a member of the Rotary Club, and use combined volunteer expertise to provide design, engineering, and medical planning for the “dream” hospice. The goal was to provide all the comforts of home in a place designed for the medical care that would meet the patients and families´ needs in the difficult moments of advanced illness.

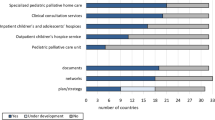

During the initial phase of the hospice being open, a wide variety of patients with advanced illness were served. The majority were in the terminal phase of advanced illness, but others include (a) patients who had the potential to return home but need to have symptoms better controlled, (b) families at risk of caregiver fatigue, (c) patients who needed prolonged chemotherapy or antibiotics that would be difficult to manage at home but did not require hospitalization, (d) some patients with a pending diagnosis who needed lodging, and (e) families who required extra time for education to learn how to care at home for their children with complex needs.

At that time, the “Villa de la Esperanza” hospice also expanded service to non-UNOP pediatric patients with non-cancer diagnoses who required palliative care. This created an additional collaboration with another foundation and a total capacity of five beds.

In the first 2 years, the hospice served many patients, improving quality of life for patients and creating an opportunity to serve families with many needs. As in UNOP, the care was provided at no cost, one or two family members could stay 24 hours a day, and visiting hours were generally open, depending upon the patient’s conditions and needs of the moment. Through the generous work of many volunteers, there were multiple group activities celebrating birthdays, Christmas and other December celebrations, and spiritual activities such as first communions, baptisms, and even marriage. End-of-life wishes of children were fulfilled, family reunions and reconciliations happened, and volunteers promoted the cause of celebrating life all the time. Many employees had never experienced working in care at end of life, and there were many learning and teaching opportunities.

Moments to Grow

In 2013 we are approached by another volunteer, Jorge Mini, who mentioned the need to open a hospice and was unaware of the existence of the “Villa de la Esperanza” hospice , but we decided to put them in contact and they materialized together a more ambitious dream. At another place of the city, they decided to build a building in which the structure was designed for the care of patients with complex diseases. This structure would have ten individual rooms, and each area would have easy access by wheelchair or if necessary by stretcher. In addition the area of the rooms would be larger with greater comfort for the patient and his family. The bathrooms were also designed to facilitate access; they were building a space based on a hospice and not adapting the existing construction to work as a hospice.

For 2 years, work continued with the foundation led by Myriam, Ammar Ayudando (AMMAR), who were in charge of the administrative and fundraising area, in addition to having their medical and nursing team who were the ones who gave direct care to patients under the direction of the UNOP palliative medical team. We continue these years by entering UNOP patients and patients from other centers that will need palliative care.

New Time, Multiplying the Work

In 2015, it was decided to separate the “Villa de la Esperanza” hospice who would be located in another area and would attend non-cancer child and adult patients and open their services for other hospitals of the Guatemalan health system that until now was neglected. The facilities were occupied by the Hospice “Hogar Estuardo Mini” where we would attend exclusively to UNOP patients; this represented several challenges for the team; the most important thing was to maintain in patients the continuity of care by being the same team who continued attending and getting involved in the decisions and accompanying the patients and their families; we also had to take care of obtaining resources, managing them, and improving the liaison processes between the unit and the hospice.

Learning Curves and Growth

With the influx of new patients, both hospice and non-palliative patients, a decision was made that care for the two different groups of patients would need to be separated and carried out in different locations. Several factors contributed to this decision but, by establishing a hospice specific to the UNOP patients, it became easier to unify patient care teams, manage equipment compatibility, and facilitate administration and fundraising for this high-need, rapidly growing group of patients. “Hogar Estuardo Mini” now has ten individual rooms, permanent 24-hour nursing staff, and two doctors in charge of medical care, in addition to a medical coordinator that works as the liaison between UNOP and the hospice. Nursing and kitchen staff have been increased due to demand, and the administration of fundraising and use of funds is being managed by the same foundation (AYUVI) that has helped build capacity at the UNOP (Table 2). From the time that UNOP assumed a more active role in the administration and medical care program design at “Hogar Estuardo Mini,” the number of patients has grown significantly, as demonstrated in the table below.

Barriers Found along the Way

Although the integral medicine team has now been providing palliative care for several years at UNOP and the hospice, we still have barriers that we must face. The first barrier is based on the cultural misconceptions regarding admission to the hospice. These ideas arise not only from the families of the children with terminal cancer but also from the circles of influence of each family. For Guatemalans, as part of the decision-making process, extended family, the communities where they live, as well as the religious leaders often contribute to decisions made. All these actors can influence, in small and large ways, how decisions are made about treatment or a move into hospice care. Misinformation contributes to resistance to accepting hospice care as the best form of medical care and support for patients with incurable disease. For that reason, the name was changed to “Home (Hogar).” This appears to improve acceptance by some families.

Another barrier to hospice that the integral medicine team anticipated was a potential resistance to referral to hospice by the treating oncology teams. In fact, the existence of the hospice turned out to be a positive incentive for the teams to make earlier referrals. An administrative education program for all medical staff that included visits to the hospice facility and orientation to amenities and services provided helped the UNOP staff understand the benefits of the hospice. The result was an educational multiplier for the families who heard the medical staff speak positively about the hospice and the encouraged families to consider admission, reducing their fears and resistance to admission.

The economic challenges of financially supporting and staffing a pediatric hospice have been complex. However, much effort directed at finding creative ways to obtain funds has allowed the hospice to continue to operate and grow. Transparent and ethical fundraising, the involvement of people with a genuine commitment to the hospice, and the building of strategic collaborative relationships in the community have helped the hospice to continue its work.

Permanent Values

Beyond establishing the financial and infrastructure stability to maintain the hospice, a set of shared values remains at the core of the work done in the hospice. These values are practiced daily.

We are all one: Each family is attended without distinction regarding ethnic groups, beliefs, socioeconomic group, or any other characteristic that could bias the quality of care provided to the patients.

Bereavement: The hospice and its team members and volunteers are an institution that values life, attending to suffering in all its facets and finding together, with families, the best approach to reduce that suffering. We provide ethical care that is not just for patients with conditions in which prognosis is uncertain, but we also strive to give tools to families to survive the grieving process and move forward with their lives after the loss of their child.

Self-care: All members of the hospice team receive ongoing training in grief management, terminal care, total pain, and aromatherapy. There are specific activities designed to both address and prevent burnout and compassion fatigue, so that all staff can maintain their ability to care for both themselves and their patients over time. There is a shared understanding that the work of pediatric hospice care is difficult, that it can place staff and volunteers at risk for attrition, and that learning about and participating in activities to prevent burnout is important.

Spiritual care: Spiritual care and support of different beliefs in the spiritual domain is an important and respected part of the care provided to patients and families in the hospice. A team of volunteers is continuously available to serve the families who are going through difficult times. The population in Guatemala is mostly Catholic and Protestant, but in some cases there are leaders from the Mayan religion who attend to the spiritual needs of the family members and patients.

Children as children: We have learned that at all times the child is a child, so providing an environment that encourages and supports play, fun, and companionship helps our pediatric patients maintain their lives in childhood, despite the hard moments that they have faced and continue to experience.

Physician support: An important aspect of the success of the hospice that should be mentioned is the enthusiastic acceptance of the hospice by the oncologists and pediatricians of UNOP. Their belief in and support of the care provided at the hospice gives families more confidence when they are referred for hospice care. The involvement of the integral medicine team from the time of diagnosis, with the ongoing clinical presence in the hospice, creates a true continuity of care that is very helpful to both families and staff. This clearly impacts the decision-making process and reduces the suffering and impact of treatment of the patients.

Evaluation

One meaningful source of feedback and evaluation of the impact of our hospice comes from the bereavement meetings that are held twice a year. Families whose children have died in the hospital, in the hospice, or at home come together for grief support. The families of children who have died in hospice are more frequent attenders of the bereavement support events. Families often go to both the hospital and the hospice to express their thanks to the staff for the care their children received. We often see parents return, 1 or 2 years after their child’s death, to volunteer and also become advocates in their communities for seeking help for children with cancer early after a cancer diagnosis is presented.

As described earlier, we have a small group of non-palliative patients receiving treatment that stay at the hospice. They frequently ask to be readmitted if there is space in the hospice because they feel cared for there. And although this is not the team’s primary goal, there is a sense that publicity, parent and family education, and the daily work done in the hospice are contributing to a change in the mindset of the Guatemalan people about the meaning and value of hospice care.

Last Reflections

Although the resources of Guatemala are very limited, as are the resources of many countries in our region, our team believes there is no excuse for failing to provide quality care. There are only excuses that justify not caring enough to fight for what our patients need and deserve. It is important to have a dream. When you have a dream, doors will open, and projects can be achieved. Although there are countries with more resources and better laws to promote the development of palliative care, it is possible to make a precious jewel, like our hospices, in more difficult circumstances. We still have work ahead, a population to educate, patients to attend to, and projects to carry out, but we do this work with one eye on the future and both feet firmly in the present with our patients currently experiencing the struggles of life-threatening illness. We continue to fundraise and to spread the word about the value of improved quality of life even when time is short. The hospices of both “Villa de la Esperanza ” and “Hogar Estuardo Mini ” are both ambitious projects that have remained true to their principles and values since they opened their doors. This is the story of our dream come true and of our experience, and we hope it motivates others to make their own dreams, perhaps held for years, come true.

References

Guatemala IN. Censo Poblacional. Guatemala 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, G. d. (201). Censo 2014. Guatemala.

Pediatrica UN (octubre de 2019). Informe estadistico. Guatemala, Guatemala, Guatemala.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bustamante, L.M., Rivas, S., Valverde, P. (2021). Pediatric Hospice Experience in Guatemala: Our History. In: Silbermann, M. (eds) Palliative Care for Chronic Cancer Patients in the Community. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54526-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54526-0_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-54525-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-54526-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)