Abstract

Biogeographical studies for Neotropical polistines are very recent and with scarce information. For instance, there is a paucity of discussions linking multiple sources of biological data (e.g., morphological, molecular, and physiological) with historical processes. Nevertheless, in this chapter, we reviewed biogeographical hypotheses for some genera of Neotropical social wasps such as Angiopolybia, Apoica, Brachygastra, Chatergellus, Epipona, Mischocyttarus, Polistes, Pseudopolybia, and Synoeca.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

13.1 Introduction

Biogeographical hypotheses for Neotropical polistines (Vespidae: Polistinae) are very recent and lack information. Hence, many issues remain unresolved or have never been discussed for the subfamily. This gap in our knowledge is due to the absence of discussions linking multiple sources of biological data (e.g., morphological, molecular, and physiological) with historical processes (Carvalho et al. 2015a). Interesting topics such as colonization routes, population genetics, divergence times, and phylogeography were hitherto little explored in social wasps (for exceptions see Menezes et al. 2015, 2017, 2020), limiting our ability to reach a better understanding of the biogeographical patterns and evolutionary processes behind the diversity of the group.

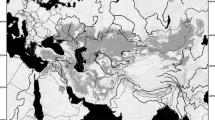

The first biogeographical hypothesis suggested that the social wasps probably originated in the tropics and it could be explained by the high diversity of species in this region (Wheeler 1922; Richards and Richards 1951). According to this hypothesis, the Vespinae/Polistinae ancestral group probably occurred in Southeast Asia, which can be sustained by the occurrence in sympatry in the eastern tropics of the three subfamilies that present social behavior (Stenogastrinae, Vespinae, and Polistinae), by the presence of ancestral forms in the nest architecture (West-Eberhard 1969), and by the less diversity of morphological traces (Van der Vecht 1965) of the species in that region. Such information support Van der Vecht (1965) hypotheses. According to these assumptions, the dispersion of polistines to the New World would have occurred across the Bering Strait during the Middle Tertiary, and the wide distribution of these wasps in the New World would probably have been achieved after the last ice age (Richards 1978).

Contrastingly, Carpenter (1981) criticized the relationship between center of diversity and origin and suggested that the distribution pattern of these wasps is “broadly Gondwanic.” Furthermore, Carpenter (1993) suggested that the separation between Africa and South America during the Early Cretaceous (~120–100 million years ago) was an important event in the evolutionary history of the group. Carpenter (1996) also reviewed the two main hypotheses on Polistinae biogeography and additionally performed component analysis for the subgenera of Polistes Latreille, 1802. The cladograms obtained in that study corroborated the idea of the Gondwana distribution of the subgenera and rejected the expected dispersal across the Bering Strait (as defended by Van der Vecht 1965; Richards 1973, 1978).

Phylogenetic inferences has provided valuable information regarding the evolutionary history of Neotropical social wasps. Polistes, for example, has been the better studied genus in this sense, and it is suggested that all subgenera of the Old World are invariably positioned at the base of the proposed phylogenetic trees, supporting the hypothesis of the center of origin in the Old World, and that the subgenera of the New World are derived (Carpenter 1996; Arévalo et al. 2004; Pickett and Wenzel 2004; Pickett et al. 2006; Pickett and Carpenter 2010; Santos et al. 2015). Thus, taking into account the phylogenetic positioning of the Polistes subgenera, this is a strong evidence for a more recent colonization in the western tropics (Carvalho et al. 2015b). In the same way, considering that the Mischocyttarini Carpenter 1993 and Epiponini Lucas, 1867 tribes only occur in the Neotropics and that no fossil of these groups has been found in the Old World, it is believed that both tribes appeared in the New World after the separation of Africa and South America (~120 million years ago) (Carvalho et al. 2015a).

13.2 Biogeographical Hypotheses for Polistes

The most recent hypothesis for the colonization process of the New World Polistes species suggests that during the Cretaceous, the transoceanic dispersion of Southeast Asia, following a single route, first reaches South America and later North America (Santos et al. 2015). Such a phenomenon is usually dismissed as unlikely due to the seemingly overwhelming scale of the geographical barrier involved – Pacific Ocean. However, there is evidence for other cases of arthropods that have surpassed oceanic barriers (Sharma and Giribet 2012), as well as a high frequency of natural oceanic dispersion by some species (Sharma and Giribet 2012). Considering the clear dispersal ability of Polistes, as evidenced by its cosmopolitan distribution, as well as its high colonization success following human introductions, a scenario of transoceanic dispersal remains plausible (Santos et al. 2015).

In addition, there is a general perception that Polistes as a whole may have a Gondwanan origin, a possibility that cannot be ruled out under the results of the current analyzes performed for the group. In the last work (Santos et al. 2015), only one species from the Afrotropics was represented in the phylogenetic analyses. The inclusion of further African species probably could lead to Africa as the ancestral area for the Polistes (Polistes) clade and for the Polistes of the New World (Santos et al. 2015; Carvalho et al. 2015b).

Phylogenetic studies with Polistes using morphological, molecular, and behavioral data established the phylogenetic basal positions of the Old World subgenera (Carpenter 1996; Arévalo et al. 2004; Pickett and Wenzel 2004; Pickett et al. 2006; Santos et al. 2015) but have not entirely resolved the relationships among derived New World groups. Pickett et al. (2006) carried out a meta-analysis using both previously available and new data to propose a robust phylogeny for this group. For example, the study placed Polistes sensu stricto as the sister group of the New World subgenera, which are arranged into five subgenera disposed in three main clades: (Aphanilopterus + ((Palisotius + Epicnemius) + (Onerarius + Fuscopolistes))). However, Santos et al. (Santos et al. 2015) performed an analysis using a larger number of taxa, molecular and morphological data, and established Polistes (Polistela) as the sister group of the other New World Polistes subgenera, and forming three main clades: (Epicnemius + ((Fuscopolistes + Onerarius) + (Palisotius + Aphanilopterus))).

While the subgenera Polistes (Onerarius) and Polistes (Palisotius) have a wide distribution in the Americas and Polistes (Fuscopolistes) have a distribution typically Nearctic, Polistes (Epicnemius) contains species widespread in Central and South America that are not very informative from the perspective of the progression rule principle and are not very informative from a biogeographical point of view. Within the subgenus Polistes (Aphanilopterus), three clades are separated and exhibit two phylogeny-distribution patterns (Santos et al. 2015); one clade apparently tracked the colonization route from eastern South America toward the Amazon, Central America, and North America; and two clades reveal spatial progression from North America toward eastern South America. Such data strengthens the round-trip hypothesis proposed by Carvalho et al. (2015b) that predicts an early colonization wave from eastern South America toward the west – only seen in Polistes (Aphanilopterus) – and multiple waves from the Amazon Forest toward the east , a route recorded in most living New World Polistinae.

13.3 Biogeographical Hypotheses for Mischocyttarus

Mischocyttarus de Saussure, 1853, is divided into 11 subgenera and grouped into 2 main clades: Clypeopolybia and Mischocyttarus sensu stricto and a second clade formed by the other species (Silveira 2008). However, Clypeopolybia exhibits polytomies and is not very informative from the biogeographical point of view. Mischocyttarus sensu stricto contains Mischocyttarus acunai Alayo which presents distribution in North and Central America; Mischocyttarus tomentosus Zikán and Mischocyttarus smithii (de Saussure) both distributed in northwestern Neotropics; and Mischocyttarus drewseni de Saussure is widely distributed in the Neotropics.

The second major branch has the subgenus Monogynoecus as the most basal. A review of the distribution of species included in this subgenus reveals that eight of the ten species are restricted to the northwestern Neotropics. However, there is no progression of species relationships in the phylogeny to allow the proposal of ancestral or more recent areas for this lineage. In contrast, phylogeny-distribution inferences are evident in this branch for the subgenera Mischocyttarus (Kappa) and Mischocyttarus (Omega). All ancient species included in the phylogeny of both subgenera are those from the northwestern and/or central Neotropics, whereas the more derived species Mischocyttarus (Kappa) funerulus Zikán and Mischocyttarus (Omega) buyssoni (Ducke) are only found in the eastern Neotropics and discretely in the central region of Brazil (see Carvalho et al. 2015b).

13.4 Biogeographical Hypotheses for Some Genera of Epiponini

The Epiponini tribe consists of 19 genera with Neotropical distribution, but there are few biogeographical studies for the group. In fact, more extensive biogeographical studies were carried out only for the genera Brachygastra Perty, 1883 (Silva and Noll 2014), and Synoeca de Saussure, 1852 (Menezes et al. 2015, 2017). In addition, for some genera of Epiponini, distribution and phylogeny information were combined to assist in the elaboration of a proposal for possible dispersal and colonization routes for Neotropical social wasps (Carvalho et al. 2015b). Recently, Menezes et al. (2020) performed a phylogenomic and biogeographic study for Epiponini. This study indicates Amazonian as the major source of Neotropical swarm-founding social wasp diversity.

Brachygastra is widely distributed, occurring from the Southern United States to southern Brazil. Silva and Noll (Silva and Noll 2014) combined phylogenetic information and geographic distribution data of Brachygastra species, and they suggested a possible influence of a terrestrial bridge between the northern and southern hemispheres, as well as a probable origin of the genus in northern South America.

The first molecular phylogeny for a genus of Epiponini was carried out to investigate the phylogenetic relationships and biogeographical history of the Synoeca species (Menezes et al. 2015). In this study, based on analyzes of divergence time and historical biogeography, the authors proposed an Amazonian origin and three main dispersion events for the group. The oldest dispersal route probably occurred in southern South America between the Amazon and Atlantic forest. A second route occurred from the Amazon toward Central America via the Isthmus of Panama. Finally, the last and most recent colonization route occurred toward the Brazilian northeast between the Amazonian and Atlantic forests.

In addition, the first phylogeographic study on Neotropical social wasps was performed by Menezes et al. (2017) for Synoeca species, specifically Synoeca cyanea (Fabricius) and Synoeca ilheensis Lopes and Menezes (treated in the work as Synoeca aff. septentrionalis). Based on multiple sources of data (multilocus DNA sequences, climatic niche models, and chromosome features) and analytical methods, the authors proposed a contrasting pattern of historical colonization, south-north (Synoeca cyanea) and north-south (Synoeca ilheensis), and clinal chromosomal variation along the Brazilian Atlantic Forest.

Other Epiponini genera that had previous phylogenies and geographic distribution data available were analyzed in a biogeographical context by Carvalho et al. (2015b) with the aim of proposing dispersion events carried out by Neotropical social wasps.

In the genus Angiopolybia Araujo, 1946, Angiopolybia pallens (Lepeletier) presents the widest distribution and occurs from Panama to the east of South America. This species has a disjoint distribution between the Amazon and the Atlantic Forest, where it was suggested that the western lineages are more derived in relation to the Atlantic populations (Carvalho et al. 2014). The other three species (Angiopolybia obidensis (Ducke), Angiopolybia paraensis (Spinola), and Angiopolybia zischkai (Richards)) are exclusive in the northwest of the Neotropics.

Apoica Lepeletier, 1836, is widely distributed in the Neotropics and consists of ten species. The only available phylogeny for the genus was proposed by Pickett and Wenzel (2007), but did not completely resolve the relationships among species. However, Apoica arborea de Saussure is sister of the other species of the group, and it occurs in the northwest of the Neotropics and central Brazil. Some species such as Apoica flavissima van der Vecht, Apoica gellida van der Vecht, Apoica pallida (Olivier), and Apoica strigata Richards are widely distributed in the Neotropical region, occurring both in dry areas of the Cerrado and Caatinga and in wetlands of the Amazon and Atlantic Forest. In addition, Apoica pallens (Fabricius) and Apoica thoracica du Buysson are widely distributed throughout the Atlantic Forest.

For Chatergellus Bequaert, 1938, which has a distribution from Costa Rica to Southeastern Brazil, two species with apomorphic characteristics of the genus Chatergellus zonatus (Spinola) and Chatergellus sanctus Richards occur in the Amazon and Atlantic Forest and eastern portion of South America, respectively. Chatergellus communis Richards and Chatergellus atectus Richards, with plesiomorphic characteristics, occur discretely in central Brazil and North and Central America, respectively. All other species are restricted to the northwest of the Neotropics.

Epipona Latreille, 1802, has an Amazonian distribution; most of species are endemic to the northwest of the Neotropics. However, Epipona tatua (Cuvier) and Epipona media Cooper are also found discreetly in the Atlantic Forest in the states of Bahia, Espírito Santo, and São Paulo.

Pseudopolybia de Saussure, 1863, presents a distribution in the Amazon region, Atlantic Forest, and central Brazil. Pseudopolybia langi Bequaert and Pseudopolybia difficilis (Ducke) are endemic to the northwest of the Neotropics, while Pseudopolybia vespiceps (de Saussure) and Pseudopolybia compressa (de Saussure) are the only species that also colonized all of South America, being considered the two species of the genus with plesiomorphic characteristics.

These genera were discussed biogeographically based on current phylogeny and distribution; however, such conclusions may not be considered conclusive. Additional assessments using phylogeographic approaches , mainly within diverse genera and groups of species within social wasps, are recommended to establish more robust conclusions. In addition, particular analyzes of widely distributed species may clarify important questions about the colonization and routes used by Polistinae in the Neotropical region.

References

Arévalo E, Zhu Y, Carpenter JM, Strassmann JE (2004) The phylogeny of the social wasp subfamily Polistinae: evidence from microsatellite flanking sequences, mitochondrial COI sequence, and morphological characters. BioMed Central Evolutionary Biology 4:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-4-8

Carpenter JM (1981) The phylogenetic relationships and natural classification of the Vespoidea (Hymenoptera). Syst Entomol 7:11–38

Carpenter JM (1993) Biogeographic patterns in Vespidae (Hymenoptera): two views of Africa and South America. p. 139-154. In: P Goldblatt (ed) Biological relationship between Africa and South America. New Haven, Yale University Press.

Carpenter JM (1996) Phylogeny and biogeography of Polistes. In: Turillazzi S, West-Eberhard MJ (eds) Natural history and evolution of paper-wasps, vol Xiv. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, Tokyo, pp 18–57. 400p

Carvalho AF, Santos GMM, Menezes RST, Costa MA (2014) Genetic diversity of Angiopolybia pallens (Lepeletier) (Hymenoptera, Vespidae, Polistinae) explained by the disjunction of South American rainforests. Genet Mol Res 13:89–94

Carvalho AF, Menezes RST, Somavilla A, Costa MA, Del Lama MA (2015a) Polistinae biogeography in the Neotropics: history and prospects. J Hymenopt Res 42:93–105

Carvalho AF, Menezes RST, Somavilla A, Costa MA, Del Lama MA (2015b) Neotropical Polistinae (Vespidae) and the progression rule principle: the round-trip hypothesis. Neotrop Entomol 44:01–08

Menezes RST, Brady SG, Carvalho AF, Del Lama MA, Costa MA (2015) Molecular phylogeny and historical biogeography of the Neotropical swarm-founding social wasp genus Synoeca (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). PLoS One 10(3):e0119151

Menezes RST, Brady SG, Carvalho AF, Del Lama MA, Costa MA (2017) The roles of barriers, refugia, and chromosomal clines underlying diversification in Atlantic Forest social wasps. Sci Rep 7(1):1–6

Menezes RST, Lloyd MW, Brady SG (2020) Phylogenomics indicates Amazonia as the major source of Neotropical swarm-founding social wasp diversity. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 287(1928):20200480

Pickett KM, Carpenter JM (2010) Simultaneous analysis and the origin of eusociality in the Vespidae (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Arthropod Syst Phylogeny 68(1):3–33

Pickett KM, Wenzel J (2004) Phylogenetic analysis of the New World Polistes (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Polistinae) using morphology and molecules. J Kansas Entomol Soc 77(4):742–760

Pickett KM, Wenzel JW (2007) Revision and cladistic analysis of the nocturnal social wasp genus, Apoica Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Polistinae: Epiponini). Am Mus Novit 3562:1–30

Pickett KM, Carpenter JM, Wheleer WC (2006) Systematics of Polistes (Hymenoptera: Vespidae), with a phylogenetic consideration of Hamilton’s haplodiploidy hypothesis. Ann Zool Fennici 43:390–406

Richards OW (1973) The subgenera of Polistes Latreille (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 17:85–104

Richards OW (1978) The social wasps of the Americas (excluding the Vespinae). British Museum of Natural History, London, p 580

Richards OW, Richards MJ (1951) Observations on the social wasps of South America (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London, p 169

Santos BF, Payne A, Pickett KM, Carpenter JM (2015) Phylogeny and historical biogeography of the paper wasp genus Polistes (Hymenoptera: Vespidae): implications for the overwintering hypothesis of social evolution. Cladistics 31:535–549

Sharma PP, Giribet G (2012) Out of the Neotropics: late cretaceous colonization of Australasia by American arthropods. Proc R Soc B 279:3501–3509

Silva M, Noll FB (2014) Biogeography of the social wasp genus Brachygastra (Hymenoptera: Vespidade: Polistinae). J Biogeogr:1–10

Silveira OT (2008) Phylogeny of wasps of the genus Mischocyttarus de Saussure (Hymenoptera, Vespidae, Polistinae). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 52(4):510–549

Van der Vecht J (1965) The geographical distribution of the social wasps (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Proceedings of the XII International Congress of Entomology, p 440–441

West-Eberhard MJ (1969) The social biology of Polistine wasps. Misc Pub Mus Zool Univ Mich 140:1–101

Wheeler WM (1922) Social life among the insects. Lecture II. Part 2. Wasps solitary and social. Sci Mon 15:119–131

Acknowledgment

AS thanks Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas for the postdoctoral scholarship (FAPEAM – FIXAM, process number 062.01427/2018). AFC thanks Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2011/13391-2) for the PhD scholarship, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq: PCI-INMA 302376/2020-8) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for two postdoctoral fellowships. RSTM is grateful to FAPESP for postdoctoral fellowships and grants (2015/02432-0 and 2016/21098-7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Somavilla, A., Carvalho, A.F., Menezes, R.S.T. (2021). Biogeographical Hypotheses for the Neotropical Social Wasps. In: Prezoto, F., Nascimento, F.S., Barbosa, B.C., Somavilla, A. (eds) Neotropical Social Wasps. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53510-0_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53510-0_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-53509-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-53510-0

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)